-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Neutrophil-Derived CCL3 Is Essential for the Rapid Recruitment of Dendritic Cells to the Site of Inoculation in Resistant Mice

Neutrophils are rapidly and massively recruited to sites of microbial infection, where they can influence the recruitment of dendritic cells. Here, we have analyzed the role of neutrophil released chemokines in the early recruitment of dendritic cells (DCs) in an experimental model of Leishmania major infection. We show in vitro, as well as during infection, that the parasite induced the expression of CCL3 selectively in neutrophils from L. major resistant mice. Neutrophil-secreted CCL3 was critical in chemotaxis of immature DCs, an effect lost upon CCL3 neutralisation. Depletion of neutrophils prior to infection, as well as pharmacological or genetic inhibition of CCL3, resulted in a significant decrease in DC recruitment at the site of parasite inoculation. Decreased DC recruitment in CCL3−/− mice was corrected by the transfer of wild type neutrophils at the time of infection. The early release of CCL3 by neutrophils was further shown to have a transient impact on the development of a protective immune response. Altogether, we identified a novel role for neutrophil-secreted CCL3 in the first wave of DC recruitment to the site of infection with L. major, suggesting that the selective release of neutrophil-secreted chemokines may regulate the development of immune response to pathogens.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 6(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000755

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000755Summary

Neutrophils are rapidly and massively recruited to sites of microbial infection, where they can influence the recruitment of dendritic cells. Here, we have analyzed the role of neutrophil released chemokines in the early recruitment of dendritic cells (DCs) in an experimental model of Leishmania major infection. We show in vitro, as well as during infection, that the parasite induced the expression of CCL3 selectively in neutrophils from L. major resistant mice. Neutrophil-secreted CCL3 was critical in chemotaxis of immature DCs, an effect lost upon CCL3 neutralisation. Depletion of neutrophils prior to infection, as well as pharmacological or genetic inhibition of CCL3, resulted in a significant decrease in DC recruitment at the site of parasite inoculation. Decreased DC recruitment in CCL3−/− mice was corrected by the transfer of wild type neutrophils at the time of infection. The early release of CCL3 by neutrophils was further shown to have a transient impact on the development of a protective immune response. Altogether, we identified a novel role for neutrophil-secreted CCL3 in the first wave of DC recruitment to the site of infection with L. major, suggesting that the selective release of neutrophil-secreted chemokines may regulate the development of immune response to pathogens.

Introduction

Neutrophils rapidly accumulate at the site of microbial infection and recent evidence show that they play a major role in immunity to several pathogens. Neutrophils, through the early release of cytokines and chemokines, create a microenvironment critical for the shaping of the development of an antigen-specific immune response (reviewed in [1],[2]).

Analyzing the early mechanisms controlling dendritic cell migration to the skin will contribute to the understanding of the development of immunity against infections. To this end, the experimental murine model of infection with the protozoan parasite Leishmania major (L. major) was used. After parasite inoculation, most mouse strains, including C57BL/6 mice, are resistant to infection and develop a protective CD4+ Th1 immune response, while a few strains such as BALB/c mice are susceptible to infection and develop a CD4+ Th2 type of immune response (reviewed in [3]). Following infection with L. major, neutrophils are massively and equally recruited to the site of parasite inoculation in mice from both strains of mice [4],[5], and recently, early recruitment of neutrophils and their essential role in the development of L. major protective immune response was confirmed using mice infected in the ear through the bite of female sandflies [6]. Depletion of neutrophils prior to Leishmania inoculation was shown to modify the development of the CD4+ T helper immune response [5],[7],[8], however, the exact mechanism(s) involved in this early process remain(s) to be determined.

Once exposed to L. major promastigotes, neutrophils from mice resistant or susceptible to infection were reported to develop distinct phenotypes including differential expression of Toll-like receptors and cytokine secretion [9]. Neutrophils could therefore create a microenvironment in the skin and influence that of skin draining lymph node, determining the development of the antigen-specific immune response. Dendritic cells, the most efficient antigen presenting cells, will be critically involved in this process. Indeed, following infection with L. major, dendritic cells have been reported to be crucial in the resistance to infection [10],[11], reviewed in [12]. Thus, considering the massive presence of neutrophils recruited to the site of parasite inoculation within the first day of infection, we hypothesized that crosstalk between neutrophils and dendritic cells at the site of infection might shape the development of the L. major specific immune response. DCs present in the L. major inoculated skin are trafficking from the epidermis/dermis, or recruited from the blood or/and from the bone marrow. They may include Langerhans cells [13], dermal DCs [14], as well as the rapidly differentiating monocyte-derived DCs [15],[16].

In the present study, we have analyzed the role of neutrophil-derived chemokines in the recruitment/trafficking of dendritic cells in the skin, during the first days of infection with Leishmania major. Although several chemokines have been reported to attract immature DC, the particular role of neutrophil-secreted chemokines in this early process has been scantily investigated. We analyzed the secretion of CCL3, CCL4, CCL5 and CCL20, as these chemokines have been reported to be both secreted by neutrophils, and to recruit immature DCs [17],[18],[19],[20].

Our results indicate first, that neutrophils from C57BL/6 L. major resistant mice secrete significantly more CCL3 than BALB/c susceptible mice in response to L. major in vitro, and second, that CCL3 is the key chemokine involved in chemoattraction of immature DCs. Infected C57BL/6 mice displayed high levels of CCL3 one day post L. major inoculation in the ear dermis, and markedly more Langherans cells, dermal DCs and monocyte-derived DCs were recruited to the site of parasite inoculation than in infected BALB/c mice, an effect mediated by neutrophil-derived CCL3. The early neutralization of CCL3 or its absence in CCL3−/− mice resulted in a delay in development of IFNγ secreting-Th1 cells, correlating with transient higher parasite load and tissue damage, a phenotype more sustained and statistically significant in CCL3−/− mice. This identifies the CCL3 secreted by neutrophils during the first days of infection as a critical chemokine involved in the recruitment/trafficking of dendritic cells, which influences the subsequent development of the immune response.

Results

In presence of L. major, neutrophils produce CCL3 which chemoattracts immature bone marrow-derived DCs

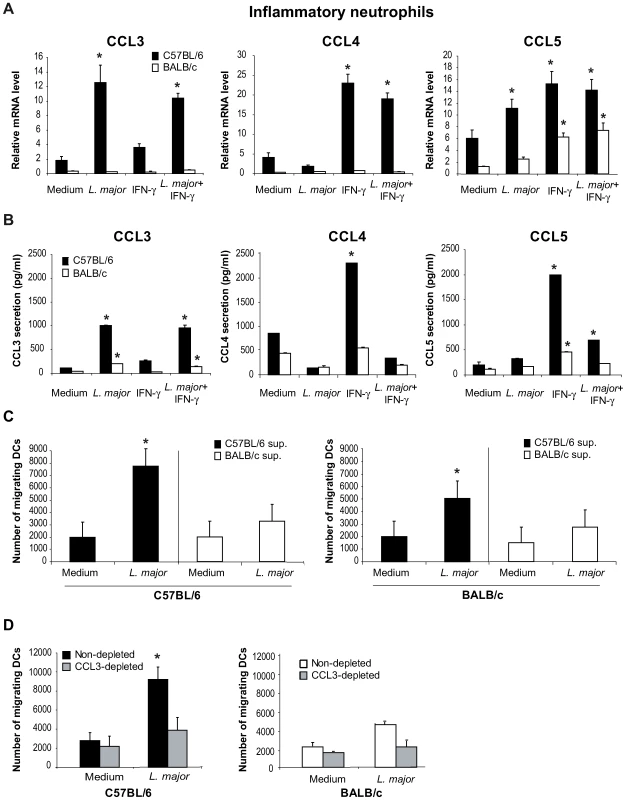

Neutrophils have been reported to secrete chemokines in response to microbial stimuli [20]. First we determined whether L. major induced the transcription and secretion of DC-attracting chemokines in inflammatory neutrophils. L. major-recruited inflammatory neutrophils were purified by MACS and incubated with L. major and/or with IFNγ, an activator of neutrophils. Sixteen hours later, cells were collected for mRNA analysis, or twenty-four hours later, cell-free supernatant was analyzed for chemokines reported to attract immature DCs. Incubation of C57BL/6 neutrophils with L. major increased both CCL3 transcript levels and protein secretion, while only a very mild effect was seen in response to IFNγ alone (Figure 1A,B). In contrast, incubation of C57BL/6 neutrophils with L. major alone did not induce a significant increase of either CCL4 mRNA or protein, but incubation of neutrophils with IFNγ induced an increase in its mRNA and release (Figure 1A,B). IFNγ and to a lower extent L. major, independently induced CCL5 mRNA, with IFNγ alone inducing the highest release of CCL5. Interestingly, the presence of L. major significantly impaired the IFNγ-induced release of both CCL4 and CCL5 (Figure 1B).

Fig. 1. In presence of L. major, neutrophils produce CCL3 which chemo-attracts bone marrow-derived DCs in vitro.

L. major–i.p. recruited C57BL/6 and BALB/c neutrophils were purified by MACS and incubated with medium, L. major (5∶1 parasite∶neutrophil ratio), IFNγ, or both. (A) Sixteen hours later, neutrophil CCL3, CCL4 and CCL5 mRNA levels were assessed by real-time quantitative RT-PCR, and (B) 24 hours after initiation of culture, chemokine content was measured in cell-free culture supernatants by ELISA. Data are the mean triplicate measurement ± SEM of neutrophil mRNA or chemokine content in the supernatants. *: p<0.05 compared to neutrophils cultured with medium only. (C) Supernatants from inflammatory neutrophils cultured in presence or in absence of L. major were tested for their chemotactic activity towards bone marrow-derived DCs in a transwell cell migration assay. The number of DCs that migrated toward neutrophil supernatant is represented. (D) DC migration was similarly assessed in response to neutrophil supernatants depleted of CCL3. *: p<0.05 as compared to values measured in response to supernatant of neutrophil incubated with medium alone. Data are expressed as mean number ± SEM of DC that migrated towards neutrophil supernatant (n = 3 per group). The results of a representative experiment out of three are shown. To determine if L. major would induce similar transcription and secretion of DC-attracting chemokines from neutrophils in the L. major-susceptible BALB/c mice, L. major recruited inflammatory BALB/c neutrophils were treated and analyzed as described above. L. major did not induce significant level of chemokine transcription nor elevated release from BALB/c neutrophils (Figure 1A,B). Neither C57BL/6 nor BALB/c neutrophils secreted or transcribed CCL20 in response to L. major, IFNγ or both (data not shown).

The selective secretion of CCL3 by L. major peritoneally-induced inflammatory C57BL/6 but not BALB/c neutrophils (Figure 1) was also measured in inflammatory dermal neutrophils recruited in the ear dermis 24 hours after L. major inoculation (Figure S1).

Altogether, these results show that, once exposed to L. major promastigotes, C57BL/6 neutrophils secrete CCL3 a chemokine known to attract immature DCs, and that the production of chemokines by BALB/c neutrophils is significantly lower in response to the parasite.

We next tested the potential effect of neutrophil supernatant on chemoattraction of immature DCs using Transwell cell migration assays. Bone marrow-derived partially immature C57BL/6 and BALB/c DCs (MHCIIlow, CD40−, B7.1−, B7.2low) were deposited on the filter of a Transwell migration assay plate, the lower compartment containing the supernatants recovered from C57BL/6 or BALB/c neutrophils exposed or not to L. major. While robust chemo-attractive activity for BM-iDCs was detected in the supernatants of C57BL/6 neutrophils exposed to L. major, no similar strong chemo-attractive activity was detectable in the supernatants of BALB/c neutrophils exposed to L. major (Figure 1C).

To assess if this chemo-attractive activity was due to CCL3 two approaches were selected. First, CCL3 was depleted from supernatant of C57BL/6 mouse neutrophils exposed to L. major, and the CCL3-depleted supernatant monitored for its iDCs chemo-attractive activity, using the Transwell migration assay. Remarkably, a significant decrease of the BM-iDC migration towards the latter supernatant was measured (Figure 1D). Second, supernatants from CCL3−/− C57BL/6 mouse neutrophils exposed to L. major were similarly tested and shown to display reduced chemo-attractive activity for +/+ BM-iDCs (data not shown).

In contrast, CCL3 depletion of BALB/c supernatants showed only a mild and not statistically significant effect on DC chemoattraction, in line with the low chemokine secretion and chemoattraction of L. major-stimulated BALB/c neutrophil supernatants (Figure 1D).

These results demonstrate that the CCL3 present in the supernatant of C57BL/6 neutrophils exposed to L. major promastigotes is the main chemokine attracting BM-iDCs in vitro.

Recruitment of DCs in the ear dermis of C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice during the first 48 hours post L. major inoculation

A significant difference in chemokine secretion was measured in our ex vivo/in vitro analysis between L. major-stimulated C57BL/6 and BALB/c neutrophils, with consequence on the recruitment of iDCs. This prompted us to investigate whether similar differences were observed in vivo. To evaluate how neutrophil and chemokine release influence dendritic cell recruitment in vivo, the model of ear skin explants was used. L. major was delivered intradermally in the ear and at different time points post inoculation, ears were recovered, and further processed as ear explants. This ex vivo approach allows the evaluation of DC recruitment in the skin dermis [21],[22].

C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were infected i.d. in the ear with L. major, and the number of cells that migrated out of infected ear skin explants was analyzed by FACS and quantified during the first 48 hours following parasite inoculation.

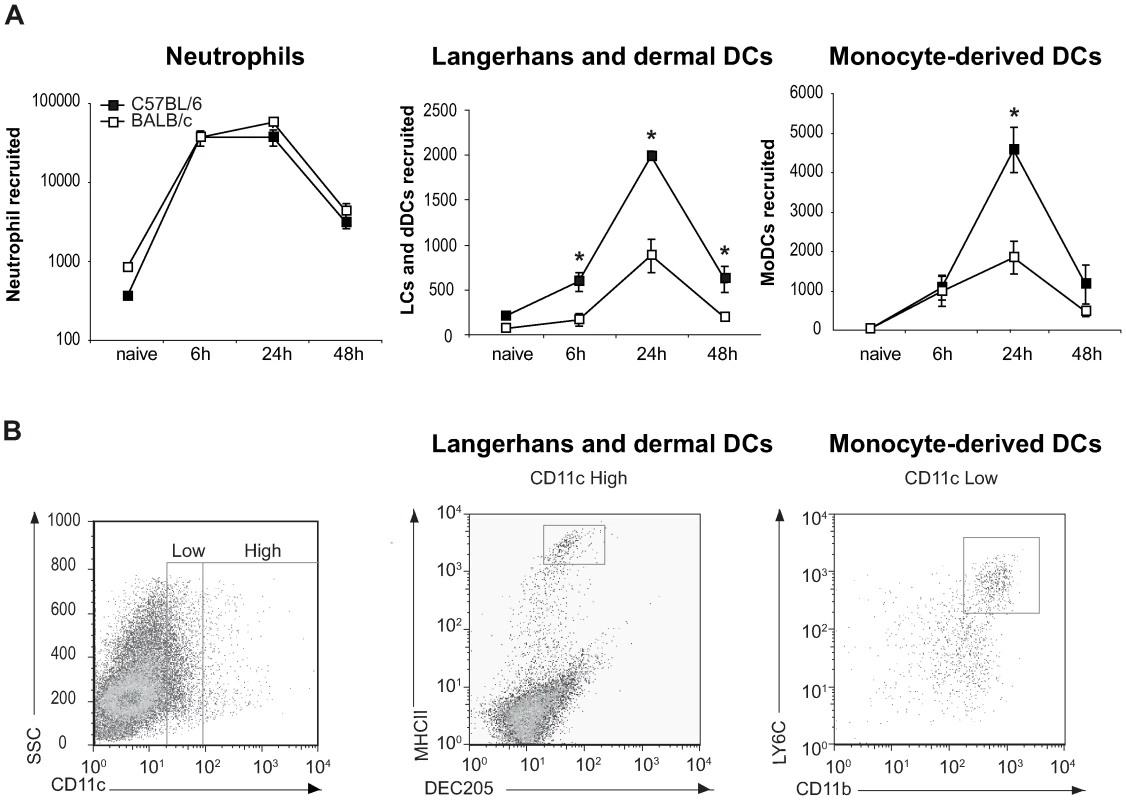

A large number of neutrophils emigrated from the ear explant within hours of parasite inoculation and their number started to decrease 48 hours later (Figure 2A). As previously reported for L. major infected footpads [4],[5], at this early stage post parasite inoculation the neutrophil number did not differ between C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice. We then estimated the number of Langerhans cells (LC) and dermal DC (dDC), defined by FACS analysis by their high surface expression of CD11c, DEC205, and MHC Class II (Figure 2B). Already six hours after infection, the number of LC and dDC migrating out of the ear dermis was significantly higher in C57BL/6 than in BALB/c mice, with the highest difference occurring twenty-four hours post infection (Figure 2A). As monocyte-derived DC (MoDC) play an important role in L. major infection [23], this cell population, characterized as being Ly6G−, Ly6C+, CD11b+ and CD11cdim (Figure 2B), was also analyzed by FACS. Twenty-four hours post L. major inoculation, a significantly higher number of MoDCs emigrated from C57BL/6 ear explants as compared to BALB/c ear explants (Figure 2A). Most of the DCs emigrating from the ears resulted from the L. major presence, while only a small percentage of DCs emigrated from the ears was due to needle-dependent injury, as illustrated by the low DC recruitment measured when medium alone was injected (Figure S2).

Fig. 2. Higher number of DCs are recruited to the ear dermis of L. major infected C57BL/6 compared to BALB/c mice.

(A) The number of neutrophils, Langerhans and dermal DCs, and monocyte-derived DCs emigrating from ear explants was measured at 0, 6, 24 and 48 hours post L. major inoculation *: p<0.05 comparing cell number in C57BL/6 versus BALB/c mice. Values from ear explants of six mice per group are expressed as mean values ± SEM . The data are representative of three separate experiments. (B) Gating strategy by flow cytometry of Langerhans and dermal DCs, and monocyte-derived DCs emigrating from L. major-infected C57BL/6 ear explants. For Langerhans and dermal DCs, MHCII and DEC205 positive cells were analyzed on CD11c+ gated cells. For monocyte-derived DCs, four colour FACS analysis was performed, CD11b+ and LY6C+ cells were analyzed on a CCD11cdim and Ly6G− gated cell population. A representative flow cytometry plot is shown. These results reveal a significant difference in DC migration during the first day post infection with L. major between C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice.

Neutrophils are required for DC recruitment to the site of L. major inoculation in C57BL/6 mice

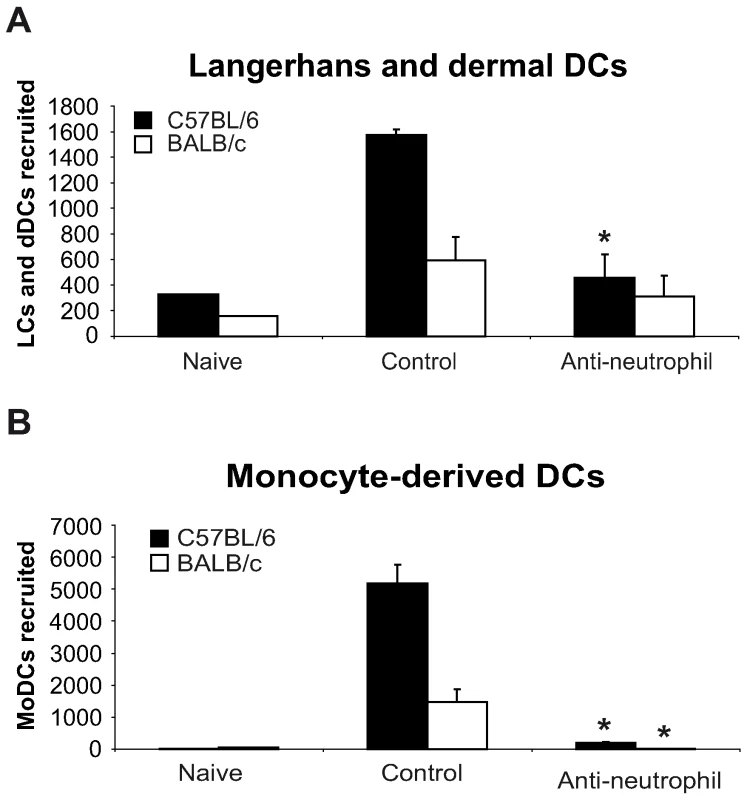

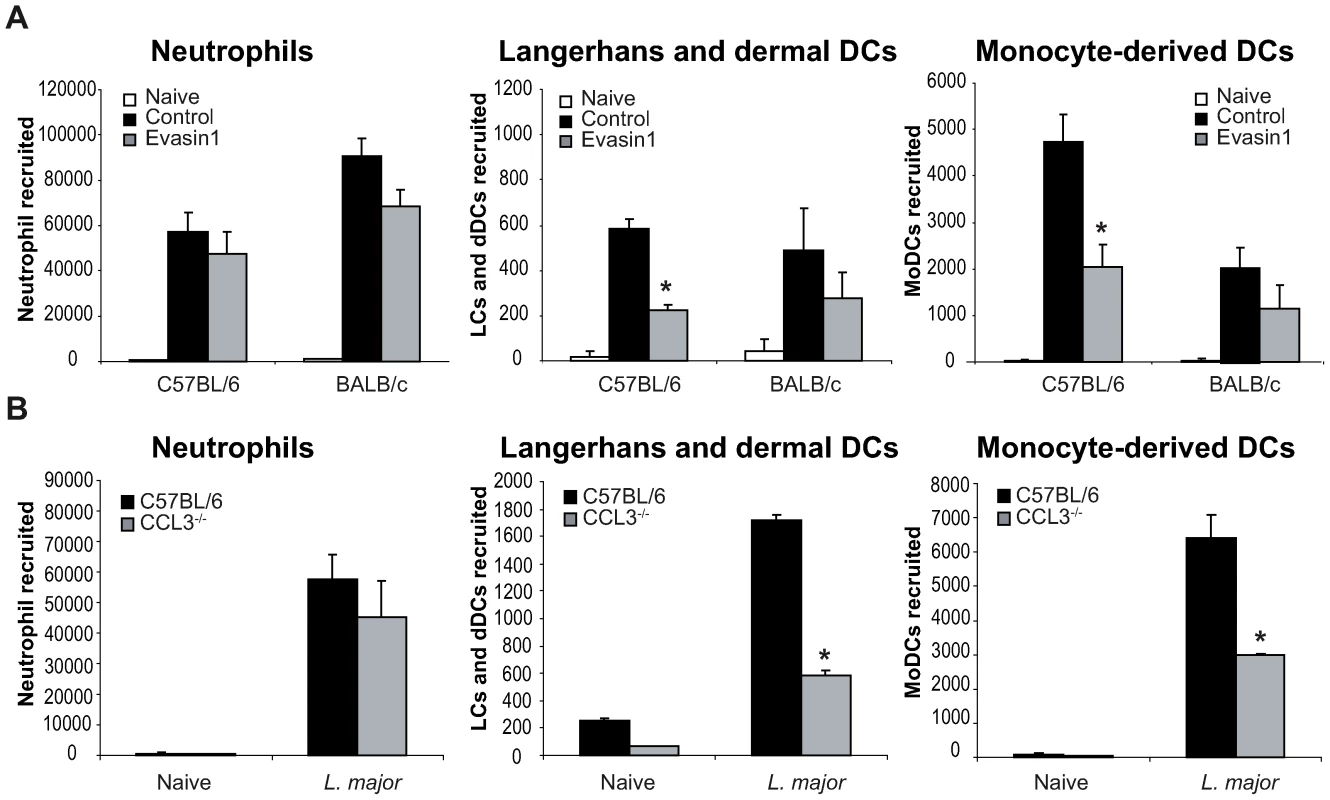

In order to further investigate whether the difference in the number of DCs recruited during the first day post L. major inoculation in C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice correlated with their distinct neutrophil functional phenotype, mice of both strains were given i.p. a single injection of the neutrophil-depleting mAb NIMP-R14, and six hours later, L. major promastigotes were i.d. delivered in one of their ears. Twenty-four hours post L. major inoculation, the DC subsets sedimenting out of the ear explants were analyzed by FACS, quantified and compared to the ones sedimenting from ear explants prepared from mice that were given a control mAb. Depletion of neutrophil significantly decreased the number of LC and dDC and abolished the recruitment of MoDC in the ear skin dermis (Figure 3A,B). These results demonstrate an essential role for neutrophils in the early recruitment of DC following inoculation of L. major.

Fig. 3. Neutrophils are essential for DC recruitment to the ear dermis following L. major promastigote inoculation.

C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were depleted of neutrophils by an injection i.p. of the NIMP-R14 anti-neutrophil mAb, or injected with a control mAb, 6 hours prior to infection i.d. with L. major stationary promastigotes. The number of (A) Langerhans and dermal DCs and (B) monocyte-derived DCs recruited in the ear dermis at 0h (naïve) or 24h following L. major inoculation was quantified and compared in mice depleted or not of neutrophils. Data are given as mean values ± SEM (n = 6 per group) and are representative of three experiments. * : p<0.05 between mice depleted or not of neutrophils. CCL3 is the major neutrophil-derived DC-attracting chemokine at the site of L. major inoculation

Since neutrophils appeared to be essential for the recruitment of dendritic cells in the first days following infection with L. major and as we have shown in vitro that the CCL3 secreted by neutrophils was critical for the recruitment of DCs, we next sought to document whether this chemokine could play an essential role in vivo.

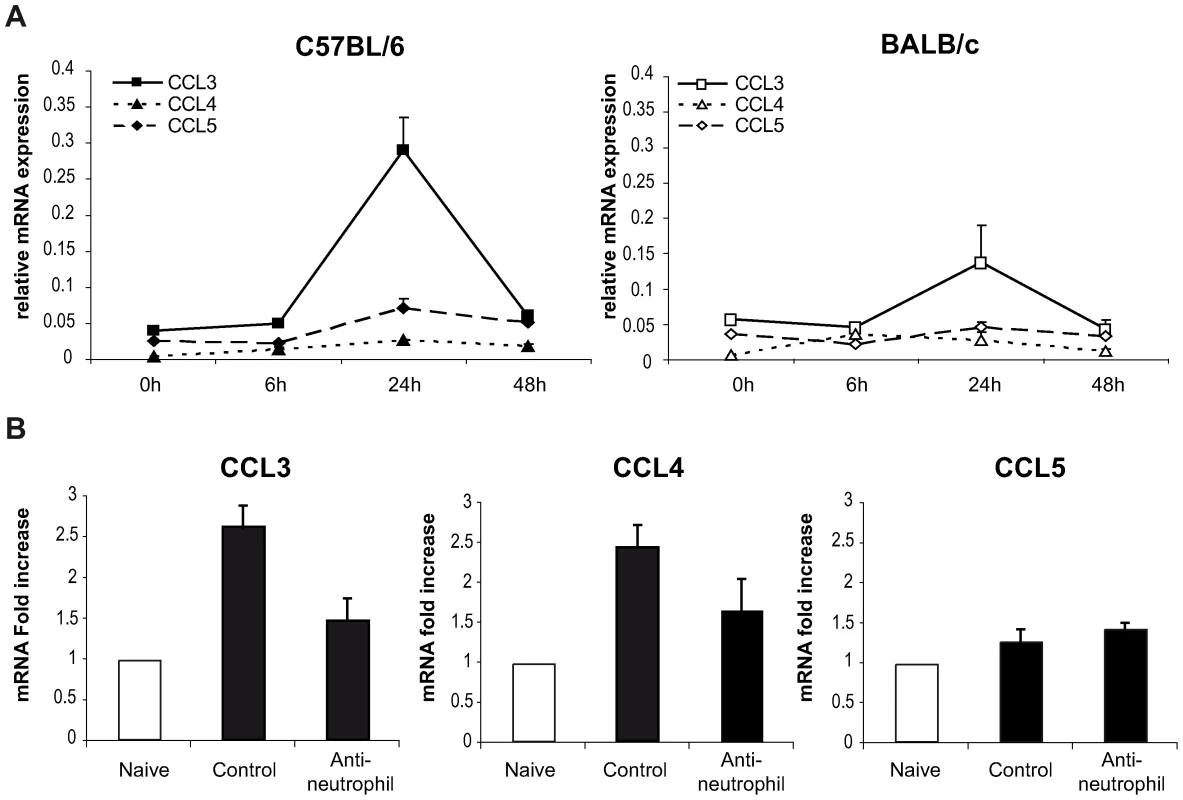

To this end, the level of chemokine mRNA was measured in L. major infected ears during the first 48 hours post infection. In C57BL/6 infected mice, CCL3 mRNA was strongly induced within 24 hours of L. major inoculation (Figure 4A), while significantly less CCL3 mRNA was induced in L. major infected BALB/c mice. L. major induced only a small increase in CCL4 and CCL5 mRNA at the site of infection (Figure 4A), while infection did not induce CCL20 mRNA (data not shown).

Fig. 4. CCL3 is a major DC-attracting chemokine in the ear dermis one day post L. major inoculation.

(A) C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were infected with L. major in the ear dermis. mRNA expression of CCL3, CCL4 and CCL5 at the site of infection was measured 0, 6, 24 and 48 hours post infection by quantitative Real-time PCR and normalized relative to HPRT mRNA levels. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM mRNA transcript levels of individual infected ear (n = 6 per time point). One representative experiment of three is shown. (B) Twenty four hours post-infection, the ear chemokine mRNA level was compared in C57BL/6 mice that were given either the NIMP-R14 neutrophil depleting mAb or a control mAb 6 hours prior to L. major inoculation in the ear. Results are represented as fold increase in mRNA levels relative to levels measured in uninfected mice given a value of 1, and are representative of two experiments. To investigate if neutrophils were responsible for CCL3 transcription at the site of infection in C57BL/6 mice, neutrophils were depleted with an injection of the NIMP-R14 mAb 6 hours prior to infection, and chemokine transcript abundance was measured in infected ears 24 hours post parasite inoculation. In L. major infected mice injected with a control mAb, CCL3 mRNA levels were increased significantly 24 hours after L. major inoculation while in neutrophil-depleted mice, CCL3 mRNA levels were much lower (Figure 4B). Among the three other chemokine transcripts - CCL4, CCL5, and CCL20 – monitored, only the CCL4 followed a transcript profile similar to the CCL3 one though with lower amplitude (Figure 4A). These data demonstrate that twenty-four hours post parasite inoculation in the ear, neutrophils contribute to most of the CCL3 and part of the CCL4 present during the first day of infection.

In order to directly establish that CCL3 acts as a key chemokine accounting for the recruitment of DCs in the L. major-loaded dermis, CCL3 was depleted in mice by treatment with Evasin-1 [24], a highly selective neutralizing chemokine binding protein with high affinity for CCL3 and to weaker affinity for CCL4 [25]. Mice were given Evasin-1 two hours prior to i.d. L. major inoculation in the ear, and DC mobilization in the infected ear explants was quantified as described above. Injection of Evasin-1 had no significant effect on the number of neutrophils that migrated out of ear skin dermis 24 hours after infection (Figure 5A). This allowed the investigation of the role of neutrophils on DC recruitment at the site of infection, under conditions when CCL3 secretion was neutralized. While injection of Evasin-1 into C57BL/6 mice resulted in significant decrease of emigration of both LC/dDC and MoDC from the ear explants, injection of Evasin-1 into BALB/c mice did not result in any similar phenotypic changes (Figure 5A).

Fig. 5. CCL3 is essential for early DC trafficking/recruitment to the site of infection following L. major inoculation.

(A) C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with Evasin-1, a chemokine binding protein that neutralizes CCL3. Twenty four hours post L. major inoculation, the number of neutrophils, Langerhans and dermal DCs, and monocyte-derived DCs, spontaneously emigrating out of ear explants was measured and compared to that obtained from ear explants from mice similarly infected but which were not given Evasin-1. * : p<0.05 between mice treated or not with Evasin-1. (B) 24 hours after infection i.d. with L. major, the number of leukocytes emigrating out of ear skin explants of CCL3−/− mice was compared to that measured in similarly infected C57BL/6 ear explants. The number of neutrophils, Langerhans and dermal DCs, and monocyte-derived DCs is presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 4 for Evasin-1 treated mice, and n = 6 for CCL3−/− mice) and are representative of three experiments. *: p<0.05 between CCL3−/− and C57BL/6 mice. To confirm the role of CCL3 in DC recruitment in vivo, C57BL/6 mice or mice genetically deficient in CCL3 (CCL3−/−) on the C57BL/6 genetic background, were infected with L. major i.d., and emigration from the ear explants assessed as described above. As measured in mice treated with Evasin-1, neutrophil recruitment was not significantly decreased one day post infection. However, recruitment of both LC/dDC, and MoDC was significantly reduced in CCL3−/− mice (Figure 5B), confirming that CCL3 is a major chemokine involved in LC/dDC migratory properties as well as MoDC recruitment. These results strongly suggest that the CCL3 secreted by neutrophils contributes for a major part to early DC trafficking and/or recruitment in the dermis of L. major inoculated mice.

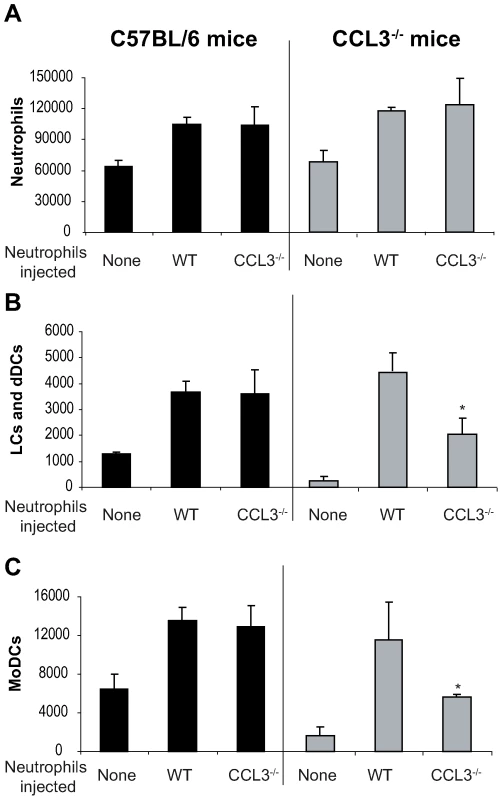

Transfer of wild type neutrophils restores DC traffic/recruitment in CCL3−/− C57BL/6 mice inoculated with L. major

So far, our data suggest that neutrophils and CCL3 contribute significantly to the early DC trafficking/recruitment to the site of L. major inoculation in C57BL/6 mice. In order to monitor whether neutrophils were indeed the major source of CCL3 that mediates DC recruitment, we transferred either C57BL/6 wild type (WT), or CCL3−/− neutrophils into CCL3−/− mice that were given i.d. L. major, and twenty-four hours later, leucocytes emigrating from the ear explants were analyzed by FACS. The number of neutrophils did not differ significantly after injection of WT or CCL3−/− neutrophils into C57BL/6 and CCL3−/− mice (Figure 6A). However, injection of WT neutrophils into ears of CCL3−/− mice strongly increased the number of LC/dDC and MoDC migrating out of the the ear explants, to levels that were comparable to those measured in WT mice injected with WT or CCL3−/− neutrophils (Figure 6B,C right panels). Even though injection of CCL3−/− neutrophils into CCL3−/− mice also increased the number of LC/dDC and MoDCs, the levels attained were significantly lower than those obtained when CCL3−/− mice were injected with WT neutrophils. These results demonstrate that the CCL3 secreted by neutrophils plays an important role in the early trafficking/recruitment of DCs cells to the site of infection during the first days of L. major infection.

Fig. 6. The CCL3 secreted by neutrophils is the major chemoattractant for DCs one day after L. major inoculation.

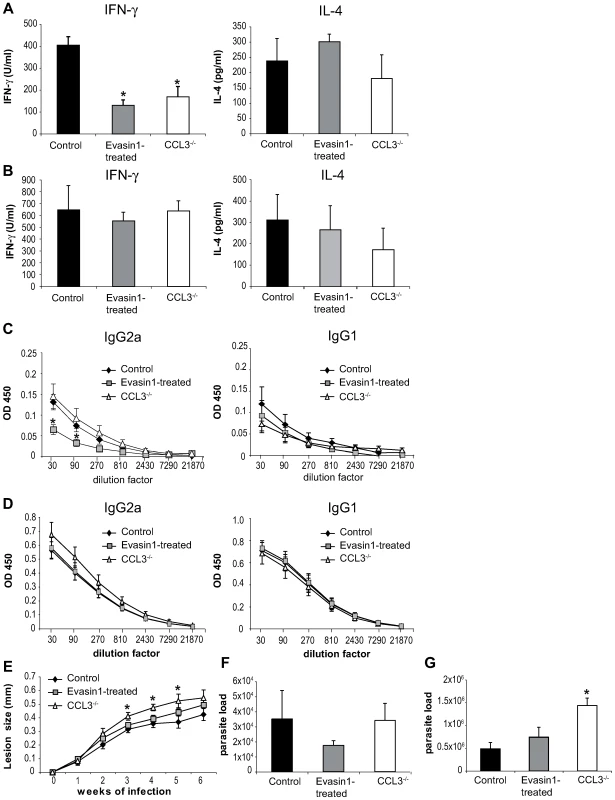

Inflammatory neutrophils from C57BL/6 or CCL3−/− mice were injected in the ear dermis of C57BL/6 or CCL3−/− mice simultaneously with L. major. (A) The neutrophils, (B) Langerhans cells, dermal DCs, and (C) monocyte-derived DCs emigrating from the ear explants were monitored 24 hours post inoculation. Data obtained from four individual mice are expressed as mean values ±SEM. The results are representative of three experiments. * : p<0.05 compared with injection with WT neutrophils. Depletion of CCL3 during the first days post L. major injection delays the onset of L. major-specific Th1 immune response

To investigate the role of CCL3 in the onset of the immune response in C57BL/6 mice, CCL3 was inhibited during the first five days post L. major inoculation by daily administration of Evasin-1. Fifteen and forty days post infection, the development of T helper immune response was assessed. L. major-specific IFNγ and IL-4 cytokine production was measured in draining lymph node CD4+ T cells, and immunoglobulin isotype switching was measured in the serum. Fifteen days post infection the transient depletion of CCL3 resulted in almost total abolition of IFNγ secretion, but no significant difference in IL-4 levels (Figure 7A). The low IFNγ levels correlated with a significant decrease of L. major-specific IgG2a and a milder but not statistically significant increase in IgG1 serum levels in Evasin-1 treated mice (Figure 7C). Low IFNγ secretion was also measured fifteen days post L. major inoculation in CCL3−/− mice (Figure 7A and 7C), in line with results from a previously published study [26], but IgG2a levels did not differ significantly from C57BL/6 controls, while IgG1 levels were slightly increased (Figure 7C). Of note, very low levels (<100pg/ml) of IL-13 and IL-17 were measured in supernatant of L. major-restimulated CD4+ T cells, with no difference between the groups (data not shown).

Fig. 7. Depletion of CCL3 during the first day post L. major inoculation delays the development of the L. major-induced Th1 immune response.

CCL3−/− mice, and C57BL/6 mice in which CCL3 was blocked by injection of Evasin-1 for the first five days post L. major inoculation, were inoculated s.c. with 3×106 L. major. CD4+ draining lymph nodes cells were prepared at days 15 (A) and 40 (B) post L. major inoculation and co-incubated with UV irradiated L. major. The resulting supernatants were monitored for their IFNγ and IL-4 content by ELISA. Data are the mean of triplicate measurement ± SEM of cytokines (n = 8 mice per group). Fifteen (C) or forty (D) days post-infection L. major-specific IgG2a and IgG1 Ab production was quantified in sera from infected mice. Data are the mean triplicate OD ± SEM of serum dilution. (E) Course of infection in CCL3−/− and Evasin-1 treated mice. Evolution of lesion size was monitored every week with a Vernier caliper. Each point represents the mean lesion size ±SEM (n = 8 per group). Parasite burden was measured by limiting dilution assay (LDA) fifteen (F) and forty (G) days post inoculation (n = 8 per group). The experiments are representative of five (15 days) and three (6 weeks) independent experiments. Six weeks post L. major inoculation, high levels of IFNγ with correspondingly high levels of L. major-specific IgG2a, and low levels of IL-4 and IgG1 characteristic of a Th1 immune response were measured, with no statistically significant difference being noted between the groups (Figure 7B, 7D). Mice treated with Evasin-1 developed slightly larger lesion than control mice but smaller lesions than CCL3−/− mice, with no statistically significant difference (Figure 7E). In contrast, development of lesion was markedly increased in CCL3−/− mice compared to C57BL/6 controls, and CCL3−/− mice harboured higher parasite load within their lesions, with a significant difference compared to Evasin-1 treated or control mice (Figure 7G).

Discussion

In this study, we focused on the role of neutrophils in the recruitment of DCs to the site of L. major inoculation, one main question addressed being whether neutrophils could transiently and locally contribute to the Langherans cell/dermal dendritic cell trafficking as well as to the recruitment of monocytes, the latter being capable to be programmed to either macrophages or monocyte-derived DCs. Our results demonstrate a previously unappreciated role of primary neutrophil extravasation, and of the CCL3 released by neutrophils in the rapid recruitment and trafficking of LC/dDC as well as of monocyte-derived DC to the site of L. major inoculation. We report here for the first time that the selective secretion of CCL3 by neutrophils is critical in vivo for the recruitment of DCs to the site of Leishmania inoculation, as revealed by markedly reduced recruitment of DCs in mice with pharmacological neutralization or absence of CCL3, and in neutrophil-depleted mice. This decrease was restored in CCL3−/− mice by the co-injection of WT C57BL/6 neutrophils together with the parasite.

CCL3 has been reported to attract neutrophils, however, our data clearly show that this chemokine does not contribute significantly to the first wave of neutrophil migration following L. major inoculation, as the number of neutrophils recruited to the site of parasite delivery one day post infection was not significantly affected by either the absence or the neutralization of CCL3.

Previous studies performed in vitro reported the transcription or/and secretion of DC attracting chemokines by neutrophils. Human neutrophils were shown to secrete molecules involved in attraction of immature DCs such as defensins [27], and CCL3 following LPS stimulation in vitro [28]. Murine neutrophils were also reported to transcribe CCL3, CCL4, CCL5 and CCL20 mRNA in response to Toxoplasma gondii exposure in vitro, with the highest induction of CCL5 mRNA [29]. In the present study, L. major induced the highest transcription and secretion of CCL3, low level of CCL5, and no transcription nor secretion of CCL4 and CCL20 in vitro. Thus, distinct pathogens can elicit different chemokine transcription patterns in neutrophils, and as reported here, the same pathogen can induce distinct chemokine release depending on the genetic background of the host. In this line, induction of TLRs in response to L. major was previously reported to differ in neutrophils from C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice, respectively resistant or susceptible to L. major [9].

The coordinate expression of chemokines and their receptors has been shown to be important in protective immunity to infection with L. major. While most studies have focused on chemokine expression in draining lymph nodes, only a few have investigated chemokine expression at the site of parasite inoculation: CCL2 and CCL3 mRNA expression were reported to be elevated already one day post infection in L. major infected footpads of C57BL/6 mice [30]. CCR2, the receptor for CCL2 and other monocyte chemoattractant proteins, was thought to be required for the generation of a protective immune response against L. major, but the differential outcome observed in CCL2−/− and CCR2−/− mice following L. major infection suggests that ligands other than CCL2 were involved in this protection [26],[31]. We also observe that in the presence of L. major, low level of CCL5 is secreted by neutrophils, but we show that it is not the major neutrophil-secreted chemokine involved in the recruitment of DCs. Indeed, during L. major infection, CCL5 expression was reported to increase selectively in C57BL/6 compared to BALB/c mice, but mainly in the late phase of infection [32]. We also report here a small transient increase in CCL4 and CCL5 mRNA one day post L. major inoculation at the site of infection in C57BL/6 mice, but CCL3 clearly showed a much higher level of transcriptional induction in these mice. Altogether, these and our studies reveal the importance of the tight control and timing of chemokine secretion during the first days post L. major inoculation.

How can the different levels of CCL3 released by C57BL/6 and BALB/c neutrophils exposed to L. major, affect the subsequent development of the immune response? Our data demonstrate that the early secretion of CCL3 has an impact on the development of the adaptive immune response, first through the recruitment of DC, and second, possibly through their activation. Whether and how neutrophils impact on the subsequent DC functions that account for T lymphocyte signaling is currently under investigation. Neutrophils have indeed been reported to deliver maturation and activation signals to DCs in BCG and Toxoplasma gondii infection [29],[33], and neutrophils were shown to associate with immature DC through interactions between DC-SIGN on immature DC and specific glycans on neutrophils [34]. In addition, neutrophil-derived ectosomes have been reported to interfere with the maturation of MoDCs [35]. Whether these DC subsets reach the skin-draining lymph node remains to be established, but it is plausible that they do, providing signals to T lymphocytes. In this line, following L. major inoculation, the early absence of CCL3 had consequences on the Th1 immune response normally developing fifteen days post parasite inoculation in the draining lymph nodes of C57BL/6 mice, preventing most of the IFNγ secretion by draining lymph node CD4+ cells. Further investigations will allow deciphering the mechanism involved in the early though transient inhibition of Th1 response following early neutralization of CCL3, and in the stepwise neutrophil-dependent processes that allow DCs to traffic from the dermis to the skin - draining lymph node at the very early stage post L. major promastigote delivery.

BALB/c and C57BL/6 neutrophils exposed to L. major have been reported to differ in the induction of cytokine secretion, with C57BL/6 neutrophils secreting IL-12, and BALB/c neutrophils secreting IL-12 p40 homodimers, blocking IL-12 signalling [9]. We report here the selective secretion of CCL3, a chemokine reported to induce IL-12 secretion in macrophages, by C57BL/6 but not BALB/c neutrophils. These differences in cytokine and chemokine secretion in L. major-exposed C57BL/6 and BALB/c neutrophils explain, at least in part, their distinct contribution to the subsequent development of T helper cells in the draining lymph node.

Several DC subsets have been reported to be involved in the development of the L. major protective immune response [10],[11] (reviewed in [12]), and infection-induced inflammatory reactions include a sharp increase in DCs at the site of parasite inoculation. L. major has been shown to be phagocytosed by dermal DCs [36], and Leishmania antigens have been reported to be transported by dermal DCs rather than by LCs [37]. Recently, de novo differentiation of monocytes into DCs, and the crucial importance of these migratory dermal monocyte-derived DCs in controlling the development of a protective CD4+ Th1 type of immune response has been demonstrated in L. major infection [23], even if a role for resident lymph node DCs is not excluded [38]. Thus the role of neutrophil-derived chemokines, together with the important contribution of CCL3 in the early recruitment of MoDC at the site of infection reported in the present study, emphasize the importance of neutrophils in recruiting the cells contributing to the priming of CD4+ Th1 cells that are essential in efficient protection against L. major infection.

Natural transmission of L. major is occurring during the bite of an infected sandfly. When mouse ears are exposed to Leishmania-hosting sand flies, neutrophils are rapidly recruited to the site of parasite inoculation, an early phenotypic trait also observed after intradermal needle inoculation of L. major [6]. It will be important to compare the two experimental systems and to explore whether factors derived from the sandfly may contribute to the early and transient wave of leucocytes as well as to their short term functions.

In conclusion, neutrophil and neutrophil-produced CCL3 appear crucial in the early recruitment of dendritic cells in the dermis, that will further direct the development of an adaptive immune response to L. major. Therefore, strategies interfering with these factors could represent a novel way to shape immune responses to pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Mice and parasites

Female BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Olac Ltd. (Bicester, UK). CCL3−/− mice were purchased from Jackson laboratory (Bar Harbor,USA). All mice were bred in the pathogen-free facility at the BIL Epalinges Center and used at 6 week of age. L. major (LV 39 MRHO/Sv/59/P strain) were maintained and grown as previously described [2]. All animal experimental protocols were approved by the veterinary office regulations of the State of Vaud, Switzerland, authorization 1266.3 to FTC, and experiments were performed adhering to protocols created by this office.

Isolation of neutrophils

Mouse inflammatory neutrophils collected by peritoneal lavage 4 hours post infection i.p. of 5.107 stationary phase L. major, were isolated and purified using MACS-positive selection as previously described [9]. Purity of neutrophils was >98% as assessed by FACS and Diff-Quick (Dade Behring) staining of cytospins. Each experiment was validated using FACS sorted neutrophils positively gated through 1A8 labeling and negatively gated with a cocktail of mAbs (against CD3, CD49b, B220, F4/80, and CD11c, see below).

Culture of neutrophils and chemokine detection

Neutrophils were cultured in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics (2.5×106 cells/ml) in the presence or absence of L. major metacyclic promastigotes (at a 5∶1 parasite∶cell ratio). The protease inhibitor aprotinin (0.4 µg/ml, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the culture to facilitate cytokine detection. Chemokine concentration in the culture supernatant was quantified by ELISA using kits from R&D systems.

mRNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative RT-PCR

Inflammatory neutrophils cultured in vitro under different conditions were harvested, mRNA extracted, cDNA synthesized and quantitative RT-PCR performed as previously described with a LightCycler system (Roche) [9]. Each cytokine transcript was normalized to the value of the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase endogenous control, represented as arbitrary values. The primers for the real time PCR were the following: CCL3: F 5′ CCA AGT CTT CTC AGC GCC AT 3′, R 5′ TCC GGC TGT AGG AGA AGC AG 3′, CCL4: F 5′ TCT TGC TCG TGG CTG CCT 3′, R 5′ GGG AGG GTC AGA GCC CA 3′, CCL5 [39], CCL20 F5′ CTT GCT TTG GCA TGG GTA CT 3′, R 5′ GTC TGT ATG TAC GAG AGG CA 3′.

CCL3 depletion

CCL3 depletion in neutrophil supernatants. Neutrophil supernatant were placed on a plate coated with antibody from the CCL3 ELISA kit (R&D systems). Depletion in supernatant was checked by ELISA. For in vivo depletion, mice were treated with Evasin-1, a CCL3 blocking protein, engineered by Merck-Serono [24]. 10 µg of Evasin-1 were injected intraperitoneally 2h before injection of the parasite. As controls, mice were injected with a similar regimen of PBS.

Generation of bone marrow derived immature DCs

Bone-marrow cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% FCS, antibiotics and 30% GM-CSF for 6 days, as previously described [40]. At day 6, the maturation of DCs was checked by FACS, measuring the levels of MHC ClassII, CD40, B7-1 and B7-2 surface molecules.

Transwell cell migration assay

Supernatant from neutrophils cultured under different conditions were placed in the lower compartment of a transwell plate (96 well plate, 3.2mm diameter 5um pore size, ChemoTx System, NeuroProbe, UK). 105 DCs were put on top of the filter. After 2h of incubation at 37°C, the number of DCs that migrate towards the supernatant were counted on Neubauer chambers using trypan blue.

Depletion of neutrophils

Mice were given i.p. -6h before L. major inoculation 250 µg of the NIMP-R14 mAb, a rat IgG2b mAb that selectively binds to mouse neutrophils [41]. This treatment was previously reported to deplete selectively neutrophils for three days [8]. As controls, mice were given i.p. the RR3-16 mAb against the Vα3.2 chain of the T-cell receptor (RR3-16, gift of R. MacDonald, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Epalinges, Switzerland).

L. major intradermal inoculation in the mouse ears and leucocyte emigration from ear skin explants

Mice were given intradermally into ear PBS or 106 stationary phase L. major promastigotes. Six, 24, 48h post L. major inoculation mice were sacrificed, the ventral and dorsal sheets of the ear were separated with forceps, the two leaflets being transferred dermal side down in a plate containing RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics at 37°C. The leukocyte populations emigrating spontaneously over 14 hours from the ear explants were then counted and stained for a FACS analysis [22]. In selected experiments, dorsal and ventral sheets of the ears were separated and the dermal side was digested with 0.1 mg/ml of Liberase TL (Roche) for 2h at 37°C. Ears from 7 mice were pooled, cut into pieces and filtered through a 40 µm filter, washed and processed for FACS sorting. Sorted neutrophils were further incubated in RPMI medium for 24 hours. Chemokine presence in neutrophil-free supernatant was then analyzed by ELISA.

FACS analysis of the leukocyte populations emigrating from the ear explants

Leukocytes emigrating from the ear explants were processed for cell surface staining. The mAb 24G2 was used to block FcRs. For analysis of cell populations several mAbs were used: PE conjugated anti-LY6G (clone 1A8), anti-CD3 (clone G4.18), anti-CD49b (clone DX5), anti-MHCII (clone M5/114.15.2), Cyc conjugated-strepatvidin, PE conjugated, APC and Cyc conjugated anti-CD11c (clone N418), FITC conjugated anti-LY6-C (clone AL-21), Cyc conjugated anti-CD11b (clone M1/70), all mAbs from e-bioscience, SanDiego, CA, US; anti-DEC205 (clone NLDC-145, AbB Serotec,UK, Ldt). Biotinilated anti-F4/80 (clone C1∶A3-1,CEDRALANE, Canada). Cells were analyzed with a FACScan (3 colors) or FACSCalibur (4 colors) (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, USA) and analyzed with the program FlowJo (Tree Star. Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Intradermal co-inoculation of neutrophils with L. major promastigotes

Four hours post i.p. inoculation of L. major peritoneal lavage neutrophils were purified by MACS. 106 C57BL/6 or CCL3−/− neutrophils were co-injected in the ear dermis with 106 stationary phase L. major promastigotes. Twenty-four hours later, mice were sacrified, ears were processed as above and emigrating cell populations analyzed by FACS.

Detection of immune response in CCL3−/− mice and in mice transiently depleted of CCL3

3×106 L. major were inoculated in the footpad of either CCL3−/− mice or +/+ mice in which CCL3 was blocked during the first five days of infection by daily injection of Evasin-1. Mice were sacrificed 15 and 40 days post - L. major inoculation in the footpad. Draining lymph node CD4+ T cells were isolated by MACS (Miltenyi Biotec), and cultured in the presence of irradiated C57BL/6 splenocytes ± UV-irradiated L. major promastigotes. Cytokine levels were measured by ELISA. Sera obtained at different time points post L. major inoculation were tested for L. major-binding IgG1 and IgG2a, and parasite burden was determined by limiting dilution assay as previously described [42].

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the Student's t-test for unpaired data.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. NathanC

2006 Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol 6 173 182

2. AppelbergR

2007 Neutrophils and intracellular pathogens: beyond phagocytosis and killing. Trends Microbiol 15 87 92

3. SacksD

Noben-TrauthN

2002 The immunology of susceptibility and resistance to Leishmania major in mice. Nat Rev Immunol 2 845 858

4. BeilWJ

Meinardus-HagerG

NeugebauerDC

SorgC

1992 Differences in the onset of the inflammatory response to cutaneous leishmaniasis in resistant and susceptible mice. J Leukoc Biol 52 135 142

5. Tacchini-CottierF

ZweifelC

BelkaidY

MukankundiyeC

VaseiM

2000 An immunomodulatory function for neutrophils during the induction of a CD4+ Th2 response in BALB/c mice infected with Leishmania major. J Immunol 165 2628 2636

6. PetersNC

EgenJG

SecundinoN

DebrabantA

KimblinN

2008 In vivo imaging reveals an essential role for neutrophils in leishmaniasis transmitted by sand flies. Science 321 970 974

7. Ribeiro-GomesFL

OteroAC

GomesNA

Moniz-De-SouzaMC

Cysne-FinkelsteinL

2004 Macrophage interactions with neutrophils regulate Leishmania major infection. J Immunol 172 4454 4462

8. McFarlaneE

PerezC

CharmoyM

AllenbachC

CarterKC

2008 Neutrophils contribute to development of a protective immune response during onset of infection with Leishmania donovani. Infect Immun 76 532 541

9. CharmoyM

MegnekouR

AllenbachC

ZweifelC

PerezC

2007 Leishmania major induces distinct neutrophil phenotypes in mice that are resistant or susceptible to infection. J Leukoc Biol 82 288 299

10. BaldwinT

HenriS

CurtisJ

O'KeeffeM

VremecD

2004 Dendritic cell populations in Leishmania major-infected skin and draining lymph nodes. Infect Immun 72 1991 2001

11. BrewigN

KissenpfennigA

MalissenB

VeitA

BickertT

2009 Priming of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in experimental leishmaniasis is initiated by different dendritic cell subtypes. J Immunol 182 774 783

12. SoongL

2008 Modulation of dendritic cell function by Leishmania parasites. J Immunol 180 4355 4360

13. StoitznerP

PfallerK

StosselH

RomaniN

2002 A close-up view of migrating Langerhans cells in the skin. J Invest Dermatol 118 117 125

14. ShklovskayaE

RoedigerB

Fazekas de St GrothB

2008 Epidermal and dermal dendritic cells display differential activation and migratory behavior while sharing the ability to stimulate CD4+ T cell proliferation in vivo. J Immunol 181 418 430

15. RandolphGJ

OchandoJ

Partida-SanchezS

2008 Migration of dendritic cell subsets and their precursors. Annu Rev Immunol 26 293 316

16. LeonB

Lopez-BravoM

ArdavinC

2005 Monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Semin Immunol 17 313 318

17. DieuMC

VanbervlietB

VicariA

BridonJM

OldhamE

1998 Selective recruitment of immature and mature dendritic cells by distinct chemokines expressed in different anatomic sites. J Exp Med 188 373 386

18. PowerCA

ChurchDJ

MeyerA

AlouaniS

ProudfootAE

1997 Cloning and characterization of a specific receptor for the novel CC chemokine MIP-3alpha from lung dendritic cells. J Exp Med 186 825 835

19. SozzaniS

SallustoF

LuiniW

ZhouD

PiemontiL

1995 Migration of dendritic cells in response to formyl peptides, C5a, and a distinct set of chemokines. J Immunol 155 3292 3295

20. CassatellaMA

1999 Neutrophil-derived proteins: selling cytokines by the pound. Adv Immunol 73 369 509

21. LarsenCP

SteinmanRM

Witmer-PackM

HankinsDF

MorrisPJ

1990 Migration and maturation of Langerhans cells in skin transplants and explants. J Exp Med 172 1483 1493

22. BelkaidY

JouinH

MilonG

1996 A method to recover, enumerate and identify lymphomyeloid cells present in an inflammatory dermal site: a study in laboratory mice. J Immunol Methods 199 5 25

23. LeonB

Lopez-BravoM

ArdavinC

2007 Monocyte-derived dendritic cells formed at the infection site control the induction of protective T helper 1 responses against Leishmania. Immunity 26 519 531

24. FrauenschuhA

PowerCA

DeruazM

FerreiraBR

SilvaJS

2007 Molecular cloning and characterization of a highly selective chemokine-binding protein from the tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus. J Biol Chem 282 27250 27258

25. DeruazM

FrauenschuhA

AlessandriAL

DiasJM

CoelhoFM

2008 Ticks produce highly selective chemokine binding proteins with antiinflammatory activity. J Exp Med

26. SatoN

AhujaSK

QuinonesM

KosteckiV

ReddickRL

2000 CC chemokine receptor (CCR)2 is required for langerhans cell migration and localization of T helper cell type 1 (Th1)-inducing dendritic cells. Absence of CCR2 shifts the Leishmania major-resistant phenotype to a susceptible state dominated by Th2 cytokines, b cell outgrowth, and sustained neutrophilic inflammation. J Exp Med 192 205 218

27. YangD

ChenQ

ChertovO

OppenheimJJ

2000 Human neutrophil defensins selectively chemoattract naive T and immature dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol 68 9 14

28. KasamaT

StrieterRM

StandifordTJ

BurdickMD

KunkelSL

1993 Expression and regulation of human neutrophil-derived macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha. J Exp Med 178 63 72

29. BennounaS

BlissSK

CurielTJ

DenkersEY

2003 Cross-talk in the innate immune system: neutrophils instruct recruitment and activation of dendritic cells during microbial infection. J Immunol 171 6052 6058

30. AntoniaziS

PriceHP

KropfP

FreudenbergMA

GalanosC

2004 Chemokine gene expression in toll-like receptor-competent and -deficient mice infected with Leishmania major. Infect Immun 72 5168 5174

31. QuinonesMP

EstradaCA

JimenezF

MartinezH

WillmonO

2007 CCL2-independent role of CCR2 in immune responses against Leishmania major. Parasite Immunol 29 211 217

32. SantiagoHC

OliveiraCF

SantiagoL

FerrazFO

de SouzaDG

2004 Involvement of the chemokine RANTES (CCL5) in resistance to experimental infection with Leishmania major. Infect Immun 72 4918 4923

33. MorelC

BadellE

AbadieV

RobledoM

SetterbladN

2008 Mycobacterium bovis BCG-infected neutrophils and dendritic cells cooperate to induce specific T cell responses in humans and mice. Eur J Immunol 38 437 447

34. van GisbergenKP

Sanchez-HernandezM

GeijtenbeekTB

van KooykY

2005 Neutrophils mediate immune modulation of dendritic cells through glycosylation-dependent interactions between Mac-1 and DC-SIGN. J Exp Med 201 1281 1292

35. EkenC

GasserO

ZenhaeusernG

OehriI

HessC

2008 Polymorphonuclear neutrophil-derived ectosomes interfere with the maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol 180 817 824

36. NgLG

HsuA

MandellMA

RoedigerB

HoellerC

2008 Migratory dermal dendritic cells act as rapid sensors of protozoan parasites. PLoS Pathog 4 e1000222 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000222

37. RitterU

MeissnerA

ScheidigC

KornerH

2004 CD8 alpha - and Langerin-negative dendritic cells, but not Langerhans cells, act as principal antigen-presenting cells in leishmaniasis. Eur J Immunol 34 1542 1550

38. IezziG

FrohlichA

ErnstB

AmpenbergerF

SaelandS

2006 Lymph node resident rather than skin-derived dendritic cells initiate specific T cell responses after Leishmania major infection. J Immunol 177 1250 1256

39. ZhangN

SchroppelB

ChenD

FuS

HudkinsKL

2003 Adenovirus transduction induces expression of multiple chemokines and chemokine receptors in murine beta cells and pancreatic islets. Am J Transplant 3 1230 1241

40. InabaK

SteinmanRM

PackMW

AyaH

InabaM

1992 Identification of proliferating dendritic cell precursors in mouse blood. J Exp Med 175 1157 1167

41. LopezAF

StrathM

SandersonCJ

1984 Differentiation antigens on mouse eosinophils and neutrophils identified by monoclonal antibodies. Br J Haematol 57 489 494

42. Tacchini-CottierF

AllenbachC

OttenLA

RadtkeF

2004 Notch1 expression on T cells is not required for CD4+ T helper differentiation. Eur J Immunol 34 1588 1596

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek HIV Controller CD4+ T Cells Respond to Minimal Amounts of Gag Antigen Due to High TCR AvidityČlánek Transit through the Flea Vector Induces a Pretransmission Innate Immunity Resistance Phenotype in

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 2- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Infekční komplikace virových respiračních infekcí – sekundární bakteriální a aspergilové pneumonie

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Pathogen Entrapment by Transglutaminase—A Conserved Early Innate Immune Mechanism

- Broadly Protective Monoclonal Antibodies against H3 Influenza Viruses following Sequential Immunization with Different Hemagglutinins

- Neutrophil-Derived CCL3 Is Essential for the Rapid Recruitment of Dendritic Cells to the Site of Inoculation in Resistant Mice

- Differentiation, Distribution and γδ T Cell-Driven Regulation of IL-22-Producing T Cells in Tuberculosis

- IFN-α-Induced Upregulation of CCR5 Leads to Expanded HIV Tropism In Vivo

- An Extensive Circuitry for Cell Wall Regulation in

- TgMORN1 Is a Key Organizer for the Basal Complex of

- Direct Presentation Is Sufficient for an Efficient Anti-Viral CD8 T Cell Response

- Immunoelectron Microscopic Evidence for Tetherin/BST2 as the Physical Bridge between HIV-1 Virions and the Plasma Membrane

- A New Nuclear Function of the Glycolytic Enzyme Enolase: The Metabolic Regulation of Cytosine-5 Methyltransferase 2 (Dnmt2) Activity

- Genome-Wide mRNA Expression Correlates of Viral Control in CD4+ T-Cells from HIV-1-Infected Individuals

- Structural and Biochemical Characterization of SrcA, a Multi-Cargo Type III Secretion Chaperone in Required for Pathogenic Association with a Host

- A Major Role for the ApiAP2 Protein PfSIP2 in Chromosome End Biology

- HIV Controller CD4+ T Cells Respond to Minimal Amounts of Gag Antigen Due to High TCR Avidity

- Fis Is Essential for Capsule Production in and Regulates Expression of Other Important Virulence Factors

- Vaccinia Protein F12 Has Structural Similarity to Kinesin Light Chain and Contains a Motor Binding Motif Required for Virion Export

- A Novel Pseudopodial Component of the Dendritic Cell Anti-Fungal Response: The Fungipod

- Efficacy of the New Neuraminidase Inhibitor CS-8958 against H5N1 Influenza Viruses

- Long-Lived Antibody and B Cell Memory Responses to the Human Malaria Parasites, and

- IPS-1 Is Essential for the Control of West Nile Virus Infection and Immunity

- Transit through the Flea Vector Induces a Pretransmission Innate Immunity Resistance Phenotype in

- Ats-1 Is Imported into Host Cell Mitochondria and Interferes with Apoptosis Induction

- Six RNA Viruses and Forty-One Hosts: Viral Small RNAs and Modulation of Small RNA Repertoires in Vertebrate and Invertebrate Systems

- The Syk Kinase SmTK4 of Is Involved in the Regulation of Spermatogenesis and Oogenesis

- Optineurin Negatively Regulates the Induction of IFNβ in Response to RNA Virus Infection

- On the Diversity of Malaria Parasites in African Apes and the Origin of from Bonobos

- Five Questions about Viruses and MicroRNAs

- A Broad Distribution of the Alternative Oxidase in Microsporidian Parasites

- Caspase-1 Activation via Rho GTPases: A Common Theme in Mucosal Infections?

- Peptides Presented by HLA-E Molecules Are Targets for Human CD8 T-Cells with Cytotoxic as well as Regulatory Activity

- Interaction of Rim101 and Protein Kinase A Regulates Capsule

- Distinct External Signals Trigger Sequential Release of Apical Organelles during Erythrocyte Invasion by Malaria Parasites

- Exacerbated Innate Host Response to SARS-CoV in Aged Non-Human Primates

- Reverse Genetics in Predicts ARF Cycling Is Essential for Drug Resistance and Virulence

- Universal Features of Post-Transcriptional Gene Regulation Are Critical for Zygote Development

- Highly Differentiated, Resting Gn-Specific Memory CD8 T Cells Persist Years after Infection by Andes Hantavirus

- Arterivirus Nsp1 Modulates the Accumulation of Minus-Strand Templates to Control the Relative Abundance of Viral mRNAs

- Lethal Antibody Enhancement of Dengue Disease in Mice Is Prevented by Fc Modification

- Quantitative Comparison of HTLV-1 and HIV-1 Cell-to-Cell Infection with New Replication Dependent Vectors

- The Disulfide Bonds in Glycoprotein E2 of Hepatitis C Virus Reveal the Tertiary Organization of the Molecule

- IL-1β Processing in Host Defense: Beyond the Inflammasomes

- Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated Herpes Virus (KSHV) Induced COX-2: A Key Factor in Latency, Inflammation, Angiogenesis, Cell Survival and Invasion

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Caspase-1 Activation via Rho GTPases: A Common Theme in Mucosal Infections?

- Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated Herpes Virus (KSHV) Induced COX-2: A Key Factor in Latency, Inflammation, Angiogenesis, Cell Survival and Invasion

- IL-1β Processing in Host Defense: Beyond the Inflammasomes

- Reverse Genetics in Predicts ARF Cycling Is Essential for Drug Resistance and Virulence

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání