-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Conflicts of Interest at Medical Journals: The Influence of Industry-Supported Randomised Trials on Journal Impact Factors and Revenue – Cohort Study

Background:

Transparency in reporting of conflict of interest is an increasingly important aspect of publication in medical journals. Publication of large industry-supported trials may generate many citations and journal income through reprint sales and thereby be a source of conflicts of interest for journals. We investigated industry-supported trials' influence on journal impact factors and revenue.Methods and Findings:

We sampled six major medical journals (Annals of Internal Medicine, Archives of Internal Medicine, BMJ, JAMA, The Lancet, and New England Journal of Medicine [NEJM]). For each journal, we identified randomised trials published in 1996–1997 and 2005–2006 using PubMed, and categorized the type of financial support. Using Web of Science, we investigated citations of industry-supported trials and the influence on journal impact factors over a ten-year period. We contacted journal editors and retrieved tax information on income from industry sources. The proportion of trials with sole industry support varied between journals, from 7% in BMJ to 32% in NEJM in 2005–2006. Industry-supported trials were more frequently cited than trials with other types of support, and omitting them from the impact factor calculation decreased journal impact factors. The decrease varied considerably between journals, with 1% for BMJ to 15% for NEJM in 2007. For the two journals disclosing data, income from the sales of reprints contributed to 3% and 41% of the total income for BMJ and The Lancet in 2005–2006.Conclusions:

Publication of industry-supported trials was associated with an increase in journal impact factors. Sales of reprints may provide a substantial income. We suggest that journals disclose financial information in the same way that they require them from their authors, so that readers can assess the potential effect of different types of papers on journals' revenue and impact.

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 7(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000354

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000354Summary

Background:

Transparency in reporting of conflict of interest is an increasingly important aspect of publication in medical journals. Publication of large industry-supported trials may generate many citations and journal income through reprint sales and thereby be a source of conflicts of interest for journals. We investigated industry-supported trials' influence on journal impact factors and revenue.Methods and Findings:

We sampled six major medical journals (Annals of Internal Medicine, Archives of Internal Medicine, BMJ, JAMA, The Lancet, and New England Journal of Medicine [NEJM]). For each journal, we identified randomised trials published in 1996–1997 and 2005–2006 using PubMed, and categorized the type of financial support. Using Web of Science, we investigated citations of industry-supported trials and the influence on journal impact factors over a ten-year period. We contacted journal editors and retrieved tax information on income from industry sources. The proportion of trials with sole industry support varied between journals, from 7% in BMJ to 32% in NEJM in 2005–2006. Industry-supported trials were more frequently cited than trials with other types of support, and omitting them from the impact factor calculation decreased journal impact factors. The decrease varied considerably between journals, with 1% for BMJ to 15% for NEJM in 2007. For the two journals disclosing data, income from the sales of reprints contributed to 3% and 41% of the total income for BMJ and The Lancet in 2005–2006.Conclusions:

Publication of industry-supported trials was associated with an increase in journal impact factors. Sales of reprints may provide a substantial income. We suggest that journals disclose financial information in the same way that they require them from their authors, so that readers can assess the potential effect of different types of papers on journals' revenue and impact.

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' SummaryIntroduction

Many medical journals require that authors and peer reviewers declare whether they have any conflicts of interest. Such knowledge can be important for readers when assessing the paper and for editors when assessing the peer review comments.

Editors can also have conflicts of interest, and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors states that: “Editors who make final decisions about manuscripts must have no personal, professional, or financial involvement in any of the issues they might judge” [1]. Furthermore, editors are advised to “publish regular disclosure statements about potential conflicts of interest related to the commitments of journal staff” [1].

Journals may have other conflicts of interest than those of their editors, and the most important of these is likely related to the publication of industry-supported clinical trials. It is important for the industry to publish reports of large trials in prestigious journals, as such reports are essential for clinical decision making and for the sales of drugs and devices [2],[3]. However, journals not only stand to gain financially through the sales of reprints, but also publication of such trials may increase their impact factors, as a large number of reprints distributed to key clinicians by drug companies will likely increase citation rates. For example, The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) sold about one million reprints to Merck of its paper on the VIGOR trial of rofecoxib [4].

One survey found that the policies on conflicts of interest for individual editors vary between journals [5], but we have not been able to identify any empirical studies on conflicts of interest at medical journals.

We investigated the influence of industry-supported randomised trials on impact factors for major general medical journals and describe the relative income from the sales of advertisements, reprints, and industry-supported supplements.

Methods

The impact factor for a given year is calculated as the number of citations in that year to papers published in the two previous years, divided by the number of citable papers published in the two previous years [6]. We focused on two time periods, citations in 1998 for randomised clinical trials (RCTs) published in 1996–1997 and citations in 2007 for RCTs published in 2005–2006, and retrieved citation data using Web of Science on the ISI Web of Knowledge [7].

On the basis of a pilot (see Text S1) that included journals categorised as “Medicine, General & Internal” in Journal Citation Reports on the ISI Web of Knowledge [8] with an impact factor of five or higher in 2007, which identified ten journals, we decided to include six major general medical journals: Annals of Internal Medicine (Annals), Archives of Internal Medicine (Archives), BMJ, JAMA, The Lancet (Lancet), and NEJM. Trials published in these journals in the two time periods were identified using PubMed's limits function for journal name, publication date, and the publication type Randomized Controlled Trial. Papers that were not full reports of trials (e.g., letters, commentaries, and editorials) were excluded. We extracted information on journal name, title, publication year, and type of support into a standardised data sheet. Data extraction and retrieval of citation data were done independently by two authors (AL, MB), and discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Type of Support

We categorised the support as industry support, mixed support, nonindustry support, or no statement about support. We defined industry support as any financial support, whether direct or indirect (e.g., grants, industry-employed authors, assistance with data analysis or writing of the manuscript, or provision of study medication or devices by a company that produces drugs or medical devices). We did not regard a study as industry-supported if the only interaction with industry was author conflicts of interest (e.g., honorariums, consultancies, and membership of advisory boards). We defined nonindustry support as any other type of financial support. Mixed support was any support provided by both industry and nonindustry sources, and no statement about support if nothing was stated in the paper.

Citations of Individual Trials and of All Papers

We identified the number of citations for each identified RCT using the function “refine by publication year” in Web of Science. This was done in July and August 2009, blinded to the study support of the individual trials. We also identified the total number of citations (the numerator of the impact factor) using the function “create citation report” in Web of Science.

In our pilot study we compared the number of citations using Web of Science with the numbers used for the “official” impact factor calculation published in Journal Citation Reports and we discovered that the numbers of citations in Web of Science were lower (see Text S1). Correspondence with the publisher, Thomson Reuters, revealed that the citations from Web of Science and Journal Citation Reports are not similar, as they are not based on the same data. For example, studies that are referenced incorrectly are only included in Journal Citation Reports. But determinants leading to a citation not being identified in Web of Science can be assumed to be random and unrelated to study type and support. As our aim was to look at the relative contribution of industry-supported trials to the impact factor, we proceeded with our planned analyses, calculating an approximate impact factor.

Denominator of Impact Factor

We identified the number of citable papers (denominator of impact factor) published in 1996–1997 and 2005–2006 for each journal using the most recent Journal Citation Report with available data.

Financial Income and Reprint Sales

In November 2009, we contacted the Editor-in-Chief of each of the six journals by e-mail and requested data on income from sales of advertisements, reprints, and industry-supported supplements (if any), as percentage of total income for the journal, and the total number of reprints sold, in both cases in 2005 and 2006.

BMJ and Lancet provided the data, but the editors of Archives, JAMA, and NEJM did not provide the data, as it was their policy not to disclose financial information. Annals forwarded our request to the publisher who declined for similar reasons.

For these four American journals, we therefore needed to use proxy data. We obtained the publicly available tax information stated in the Internal Revenue Service Form 990 (tax form required for nonprofit organizations) for 2005 and 2006 for the journal owners: American College of Physicians (ACP) for Annals, American Medical Association (AMA) for Archives and JAMA, and Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS) for NEJM. These data report on the total income from all types of publishing by the societies, and as all societies publish more than one journal, we could not obtain data for individual journals. ACP publishes three other journals in the ACP series and books; AMA publishes eight other journals in the Archives series, an additional journal, and Web-based material; and MMS publishes various article summaries in their Journal Watch series. We contacted the journal owners for confirmation of our calculations for the relative income from industry sources based on tax information. ACP confirmed our calculations, but AMA and MMS did not reply, despite numerous e-mails.

Statistical Analyses

For each journal, we compared the distribution of support of trials published in the two time periods with the Mann-Whitney U-test (two-sided). In an a priori stated sensitivity analysis, we recategorised trials with no statement about support as nonindustry supported.

On the basis of our own citation data derived from the individual trials, we compared the number of citations of trials with industry support with those with mixed support and those with nonindustry support using the Jonckheere-Terpstra test for trend (two-sided). As the category “not stated” is a mix of the three other categories we did not include this in our test. To test the robustness of our findings, we did various a priori stated sensitivity analyses (e.g., change in criteria used for industry support) (see Text S1).

We calculated what an approximate impact factor would have been, for each of the six journals for each time period, if no trials with industry support had been published; this calculation was done by excluding trials with industry support from the numerator and the denominator. We did the same calculations using a broader category of industry-supported trials that also included those with mixed support. We estimated the percentage reduction in impact factor that resulted from exclusion of these trials.

We had intended to study the association between mean number of citations to trials and percent income from reprints, but this was not possible as only the two European journals provided the data we requested.

Results

We identified 1,429 papers indexed as Randomized Controlled Trials in PubMed (see Text S1) and excluded 61 letters, three editorials, five commentaries, and seven papers that were e-published ahead of print, which yielded a total sample size of 1,353 included RCTs (651 from 1996–1997 and 702 from 2005–2006).

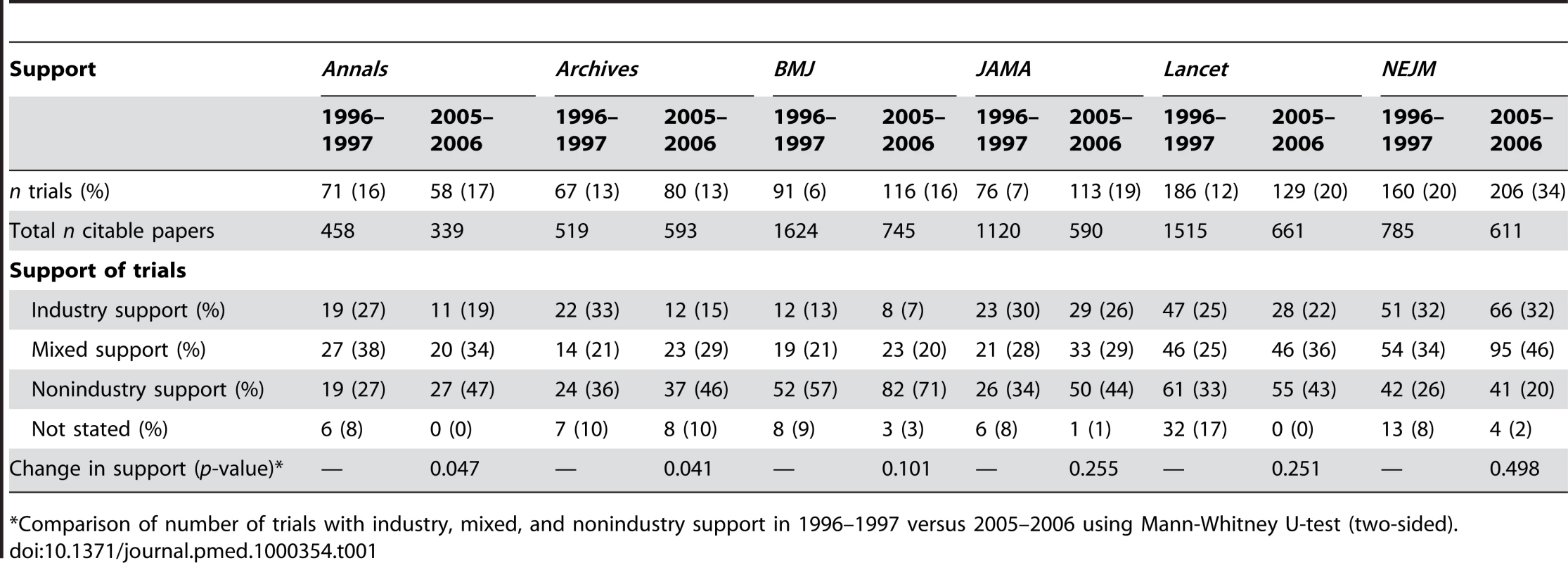

For Annals and Lancet, the number of trials decreased over time, whereas it increased for the other journals (see Table 1). The total number of citable papers decreased for all journals, except Archives. Hence, there was an increase in the proportion of trials out of all citable papers for all journals over time, with BMJ and JAMA having around a 3-fold increase and NEJM having the highest proportion of trials in both periods.

Tab. 1. Description of support of randomised controlled trials published in major general medical journals.

*Comparison of number of trials with industry, mixed, and nonindustry support in 1996–1997 versus 2005–2006 using Mann-Whitney U-test (two-sided). Type of Support

The type of support varied markedly across journals (see Table 1). In 2005–2006, NEJM had the highest proportion of trials with industry support (32%) and BMJ the lowest (7%). The proportion of trials that were industry-supported declined from 1996 to 2005 for all journals except NEJM, where it was constant. The decline was statistically significant for Annals and Archives; for BMJ, the proportion declined by nearly half (from 13% to 7%), but this was not statistically significant.

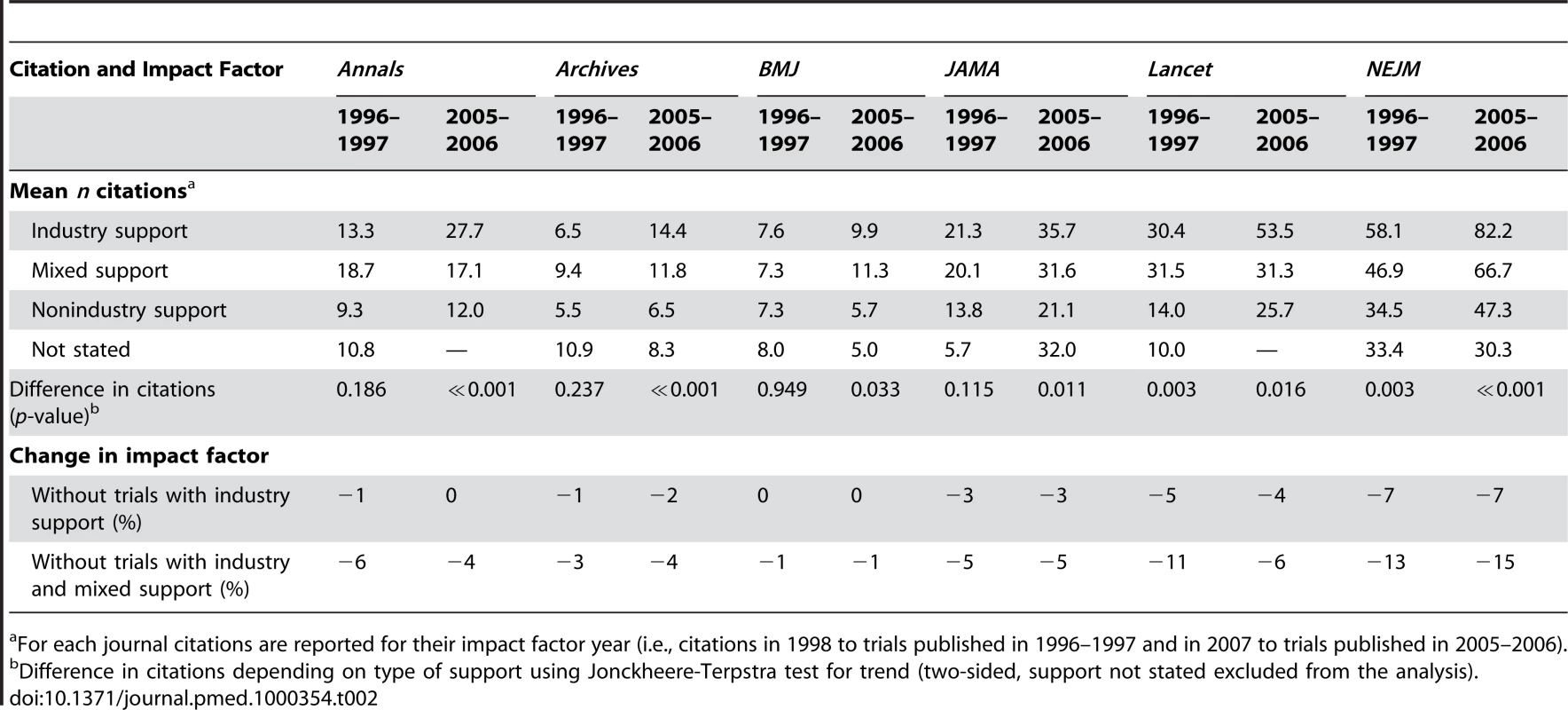

Citations of Individual Trials

For trials published in 1996–1997, there was a significant relation between the number of citations and the degree of industry support (three categories on a ranking scale) for Lancet (p = 0.003) and NEJM (p = 0.003), whereas for trials published in 2005–2006, the relation was statistically significant for all journals (see Table 2). Industry-supported trials published in Annals, Archives, and Lancet in 2005–2006 were cited more than twice as often as nonindustry trials, and one and a half times more in BMJ, JAMA, and NEJM.

Tab. 2. Citations for randomised trials published in major general medical journals and change in impact factors when industry-supported trials are excluded.

For each journal citations are reported for their impact factor year (i.e., citations in 1998 to trials published in 1996–1997 and in 2007 to trials published in 2005–2006). Our a priori defined sensitivity analyses found minor discrepancies, but overall the results were robust (see Text S1).

Approximate Impact Factor

The approximate impact factor we calculated decreased for all journals when industry-supported trials were excluded from the calculation, and the decrease was larger when trials with mixed support were also excluded (see Table 2). The decrease was highest for NEJM, followed by Lancet, whereas the impact factor of BMJ was barely affected. The decrease in approximate impact factor varied minimally between the two time periods for all journals, except for Lancet, where the decrease was 11% in 1996–1997 and 6% in 2005–2006 when trials with industry and mixed support were excluded.

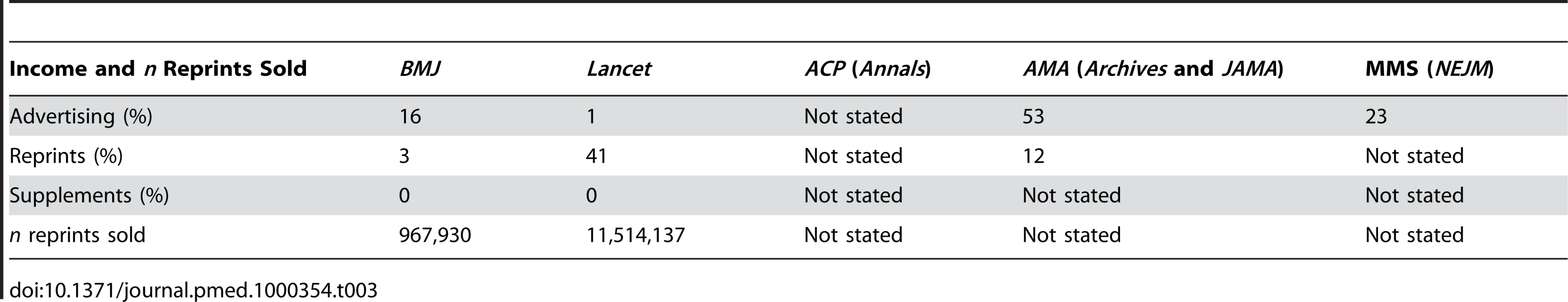

Financial Income and Reprint Sales

In 2005–2006, 16% of the income for BMJ was from display advertisements, 3% from reprints, and 0% from supplements, and 967,930 reprints were sold (see Table 3). For Lancet, the percentages were 1% from display advertisements, 41% from reprints, and 0% from supplements, and 11,514,137 reprints were sold. For ACP, the Internal Revenue Service data did not specify the income, for AMA 53% of the income was from advertisements and 12% from reprints (no data on supplements), and for MMS 23% of the income was from advertisements, whereas there were no data on reprints and supplements.

Tab. 3. Relative income of journals and medical societies from sales of advertisements, reprints, and supplements and number of reprints sold in 2005–2006.

Discussion

We found that the proportion of industry-supported trials varied widely across journals but changed very little for each journal within the studied time period. Industry-supported trials boosted the approximate impact factor we calculated for all six journals—the most for NEJM and the least for BMJ. Only the two European journals disclosed their main sources of income, and the income from selling reprints was hugely different, as it comprised 41% of the total income for Lancet and only 3% for BMJ.

We believe this is the first study that investigates potential conflicts of interest at medical journals in relation to citations and financial income from publication of industry-supported trials. Our data collection was systematic and thorough, but there are also limitations. First, we selected major general medical journals that publish many trials, and our findings may therefore not be generalisable to other journals. Second, our assumption that trials with no statement of support, or with nonindustry support, were not industry supported may have led to an underestimation, as undeclared industry involvement is common, e.g., in relation to ghost authorship by medical writers' agencies [9]. However, the proportion of trials with no statement of support was very small in the second period. Third, owing to the nature of the Web of Science database, our identified citations were not the same as those used when calculating journal impact factors in the Journal Citation Reports. But as our aim was to study the relative influence of industry-supported trials on the impact factor, this discrepancy is likely not so important, as errors in citing studies would be expected to be unrelated to the type of support they received.

A problem related to the impact factor is that so-called noncitable papers such as editorials, news pieces, and letters to the editor contribute to the numerator, but not to the denominator [10],[11]. Because of this serious deficiency in the calculation, we believe we have underestimated considerably the true influence of industry-supported trials on the approximate impact factor. For example, if we only include citations to citable papers (i.e., original research and reviews) in an analysis of trials with industry and mixed support, we find that the 2007 impact factor of NEJM decreases by 24% instead of 15%.

There are several reasons why industry-supported trials are generally more cited than other trials and other types of research. They are often large and the most used interventions are drugs, which are known to increase citations [12],[13]. One explanation might be that industry-supported trials are of higher quality than nonindustry supported trials, though there is little evidence to support this [14]. Interestingly, industry trials more often have positive results than nonindustry trials [14], the conclusions in negative trials are often presented in such a way that they appear to be more positive than they actually are [15], and positive industry trials are more cited than negative ones [12],[13]. Furthermore, sponsoring companies may employ various strategies to increase the awareness of their studies, including ghost authored reviews that cite them [16]–[19], purchase and dissemination of reprints [20], and creation of media attention [12],[21],[22]. Such strategies are likely to be predominantly used for trials favourable to the sponsors' products, and this may put editors under pressure, as they know which papers are especially attractive for the companies [3].

Editors have an interest in increasing the impact factor for their journal [23], whereas journal finances are generally regarded to be in the hands of the publisher. However, editors also have an interest in this, as they might be forced to fire staff if the journal does not remain profitable, or at least viable. The former editor of the BMJ, Richard Smith, reported that a single trial may lead to an income of US$1 million for a journal from reprint sales [21], and with a large profit margin of around 70% [3]. Journal publishers therefore have an incentive to advertise the benefits of reprints. As examples, the BMJ Group states that “Medical specialists determine the success of your product or service. They influence teaching, practice and purchase decisions within their workplace and the whole specialty. Reach them through the BMJ Group reprints service” [24], and NEJM states that “Article reprints from the New England influence treatment decisions” [25]. The editor of The Lancet, Richard Horton, has described how companies sometimes offer journals to purchase a large number of reprints and may threaten to pull a paper if the peer review is too critical [26]. For Lancet, a little less than half of the journal income came from reprints, and though this applied to only 12% of AMA's income, it could be more for its most prestigious journal, JAMA. Large incomes from reprint sales would also be expected for NEJM, as it publishes more industry-supported trials than the other journals.

This area warrants further research. Speciality journals could also be investigated, particularly as conflicts of interest there could be more pronounced as editors are often investigators themselves and the degree of industry support may vary across specialities. Influence from other types of industry-sponsored papers could also be investigated. It would also be interesting to examine whether income from advertisements can affect editorial decisions; for example, one could compare the number of advertisements from specific companies with the number of publications from the same companies in a sample of journals. Such income can be substantial for some journals [27]. When Annals published a study that was critical of industry advertisements [28], it resulted in the loss of an estimated US$1–1.5 million in advertising revenue [29]. Another source of income that should be investigated is sponsored subscriptions whereby companies pay for subscriptions for clinicians, sometimes with a cover wrap displaying a company product [30].

Although publication of industry-supported trials is favourable for medical journals we cannot tell from our results whether industry-supported trials have affected editorial decisions. The high number of industry-supported trials in NEJM could merely result from the fact that it has the highest impact factor and therefore also receives more trial reports than other journals. Nevertheless, disclosure of conflicts of interest is not about whether relationships have actually influenced decisions, but whether they potentially could have [1]. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors requires authors to “disclose interactions with ANY entity that could be considered broadly relevant to the work” [31]. We suggest that journals abide by the same standards related to conflicts of interest, which they rightly require from their authors, and that the sources and the amount of income are disclosed to improve transparency.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors 2010 Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: ethical considerations in the conduct and reporting of research: conflicts of interest. April 2010. Available: http://www.icmje.org/urm_full.pdf. Accessed 30 August 2010

2. GuyattGH

NaylorD

RichardsonWS

GreenL

HaynesRB

2000 What is the best evidence for making clinical decisions? JAMA 284 3127 3128

3. SmithR

2005 Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies. PLoS Med 2 e138 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020138

4. SmithR

2006 Lapses at the New England journal of medicine. J R Soc Med 99 380 382

5. HaivasI

SchroterS

WaechterF

SmithR

2004 Editors' declaration of their own conflicts of interest. CMAJ 171 475 476

6. GarfieldE

2006 The history and meaning of the journal impact factor. JAMA 295 90 93

7. Thomson Reuters ISI Web of Knowledge. Web of Science. Available: http://www.isiknowledge.com. Accessed 11 March 2010

8. Thomson Reuters ISI Web of Knowledge. Journal Citation Reports. Available: http://www.isiknowledge.com. Accessed 11 March 2010

9. FlanaginA

CareyLA

FontanarosaPB

PhillipsSG

PaceBP

1998 Prevalence of articles with honorary authors and ghost authors in peer-reviewed medical journals. JAMA 280 222 224

10. McVeighME

MannSJ

2009 The journal impact factor denominator: defining citable (counted) items. JAMA 302 1107 1109 Erratum in: (2009) JAMA 302 : 1972

11. MoedHF

van LeeuwenTN

1996 Impact factors can mislead. Nature 381 186

12. KulkarniAV

BusseJW

ShamsI

2007 Characteristics associated with citation rate of the medical literature. PLoS ONE 2 e403 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000403

13. ConenD

TorresJ

RidkerPM

2008 Differential citation rates of major cardiovascular clinical trials according to source of funding: a survey from 2000 to 2005. Circulation 118 1321 1327

14. LexchinJ

BeroLA

DjulbegovicB

ClarkO

2003 Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ 326 1167 1170

15. BoutronI

DuttonS

RavaudP

AltmanDG

2010 Reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically nonsignificant results for primary outcomes. JAMA 303 2058 2064

16. RossJS

HillKP

EgilmanDS

KrumholzHM

2008 Guest authorship and ghostwriting in publications related to rofecoxib: a case study of industry documents from rofecoxib litigation. JAMA 299 1800 1802

17. SteinmanMA

BeroLA

ChrenM

LandefeldCS

2006 Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med 145 284 293

18. HealyD

CattellD

2003 Interface between authorship, industry and science in the domain of therapeutics. Br J Psychiatry 183 22 27

19. PLoS Medicine Editors 2009 Ghostwriting: the dirty little secret of medical publishing that just got bigger. PLoS Med 6 e1000156 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000156

20. HopewellS

ClarkeM

2003 How important is the size of a reprint order? Int J Technol Assess Health Care 19 711 714

21. SmithR

2003 Medical journals and pharmaceutical companies: uneasy bedfellows. BMJ 326 1202 1205

22. PhillipsDP

KanterEJ

BednarczykB

TastadPL

1991 Importance of the lay press in the transmission of medical knowledge to the scientific community. N Engl J Med 325 1180 1183

23. SmithR

2006 Commentary: the power of the unrelenting impact factor–is it a force for good or harm? Int J Epidemiol 35 1129 1130

24. BMJ Group Reprints service 2010. Available: http://group.bmj.com/group/advertising/mediapack/BMJ%20Reprints_2010_row_final.pdf. Accessed 11 March 2010

25. New England Journal of Medicine Article reprints from the New England Journal of Medicine. Available: http://www.nejmadsales.org/downloads/Reprints_promotional_slim-jim_05.pdf. Accessed 11 March 2010

26. House of Commons Health Committee 2005 The influence of the pharmaceutical industry. Fourth report of session 2004–2005, Volume II. March 2005. Available: http://www.parliament.the-stationery-office.co.uk/pa/cm200405/cmselect/cmhealth/42/42ii.pdf. Accessed 11 March 2010

27. GlassmanPA

Hunter-HayesJ

NakamuraT

1999 Pharmaceutical advertising revenue and physician organizations: how much is too much? West J Med 171 234 238

28. WilkesMS

DoblinBH

ShapiroMF

1992 Pharmaceutical advertisements in leading medical journals: experts' assessments. Ann Intern Med 116 912 919

29. LexchinJ

LightDW

2006 Commercial influence and the content of medical journals. BMJ 332 1444 1447

30. Elsevier Pharma Solutions Your partner for an effective communication strategy. Available: http://www.elsevier.ru/attachments/editor/files/mod_structure_220/elsevier_pharma_solutions.pdf. Accessed 11 March 2010

31. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors 2010 ICMJE uniform disclosure form for potential conflicts of interest. July 2010. Available: http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2010

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 10- Není statin jako statin aneb praktický přehled rozdílů jednotlivých molekul

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

- Moje zkušenosti s Magnosolvem podávaným pacientům jako profylaxe migrény a u pacientů s diagnostikovanou spazmofilní tetanií i při normomagnezémii - MUDr. Dana Pecharová, neurolog

- Biomarker NT-proBNP má v praxi široké využití. Usnadněte si jeho vyšetření POCT analyzátorem Afias 1

- Antikoagulační léčba u pacientů před operačními výkony

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Systematic Evaluation of Serotypes Causing Invasive Pneumococcal Disease among Children Under Five: The Pneumococcal Global Serotype Project

- The Persisting Burden of Intracerebral Haemorrhage: Can Effective Treatments Be Found?

- Conflicts of Interest at Medical Journals: The Influence of Industry-Supported Randomised Trials on Journal Impact Factors and Revenue – Cohort Study

- An Urgent Need to Restrict Access to Pesticides Based on Human Lethality

- A Field Training Guide for Human Subjects Research Ethics

- Oral Ondansetron Administration in Emergency Departments to Children with Gastroenteritis: An Economic Analysis

- Being More Realistic about the Public Health Impact of Genomic Medicine

- Epigenetic Epidemiology of Common Complex Disease: Prospects for Prediction, Prevention, and Treatment

- Acute Human Lethal Toxicity of Agricultural Pesticides: A Prospective Cohort Study

- Information from Pharmaceutical Companies and the Quality, Quantity, and Cost of Physicians' Prescribing: A Systematic Review

- Increased Responsibility and Transparency in an Era of Increased Visibility

- Editors, Publishers, Impact Factors, and Reprint Income

- Reflections on Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 and the International Response

- Prenatal Treatment for Serious Neurological Sequelae of Congenital Toxoplasmosis: An Observational Prospective Cohort Study

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Epigenetic Epidemiology of Common Complex Disease: Prospects for Prediction, Prevention, and Treatment

- Editors, Publishers, Impact Factors, and Reprint Income

- Oral Ondansetron Administration in Emergency Departments to Children with Gastroenteritis: An Economic Analysis

- Systematic Evaluation of Serotypes Causing Invasive Pneumococcal Disease among Children Under Five: The Pneumococcal Global Serotype Project

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání