-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Association of Genetic Variants in Complement Factor H and Factor H-Related Genes with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Susceptibility

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a complex polygenic autoimmune disease, is associated with increased complement activation. Variants of genes encoding complement regulator factor H (CFH) and five CFH-related proteins (CFHR1-CFHR5) within the chromosome 1q32 locus linked to SLE, have been associated with multiple human diseases and may contribute to dysregulated complement activation predisposing to SLE. We assessed 60 SNPs covering the CFH-CFHRs region for association with SLE in 15,864 case-control subjects derived from four ethnic groups. Significant allelic associations with SLE were detected in European Americans (EA) and African Americans (AA), which could be attributed to an intronic CFH SNP (rs6677604, in intron 11, Pmeta = 6.6×10−8, OR = 1.18) and an intergenic SNP between CFHR1 and CFHR4 (rs16840639, Pmeta = 2.9×10−7, OR = 1.17) rather than to previously identified disease-associated CFH exonic SNPs, including I62V, Y402H, A474A, and D936E. In addition, allelic association of rs6677604 with SLE was subsequently confirmed in Asians (AS). Haplotype analysis revealed that the underlying causal variant, tagged by rs6677604 and rs16840639, was localized to a ∼146 kb block extending from intron 9 of CFH to downstream of CFHR1. Within this block, the deletion of CFHR3 and CFHR1 (CFHR3-1Δ), a likely causal variant measured using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, was tagged by rs6677604 in EA and AS and rs16840639 in AA, respectively. Deduced from genotypic associations of tag SNPs in EA, AA, and AS, homozygous deletion of CFHR3-1Δ (Pmeta = 3.2×10−7, OR = 1.47) conferred a higher risk of SLE than heterozygous deletion (Pmeta = 3.5×10−4, OR = 1.14). These results suggested that the CFHR3-1Δ deletion within the SLE-associated block, but not the previously described exonic SNPs of CFH, might contribute to the development of SLE in EA, AA, and AS, providing new insights into the role of complement regulators in the pathogenesis of SLE.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002079

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002079Summary

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a complex polygenic autoimmune disease, is associated with increased complement activation. Variants of genes encoding complement regulator factor H (CFH) and five CFH-related proteins (CFHR1-CFHR5) within the chromosome 1q32 locus linked to SLE, have been associated with multiple human diseases and may contribute to dysregulated complement activation predisposing to SLE. We assessed 60 SNPs covering the CFH-CFHRs region for association with SLE in 15,864 case-control subjects derived from four ethnic groups. Significant allelic associations with SLE were detected in European Americans (EA) and African Americans (AA), which could be attributed to an intronic CFH SNP (rs6677604, in intron 11, Pmeta = 6.6×10−8, OR = 1.18) and an intergenic SNP between CFHR1 and CFHR4 (rs16840639, Pmeta = 2.9×10−7, OR = 1.17) rather than to previously identified disease-associated CFH exonic SNPs, including I62V, Y402H, A474A, and D936E. In addition, allelic association of rs6677604 with SLE was subsequently confirmed in Asians (AS). Haplotype analysis revealed that the underlying causal variant, tagged by rs6677604 and rs16840639, was localized to a ∼146 kb block extending from intron 9 of CFH to downstream of CFHR1. Within this block, the deletion of CFHR3 and CFHR1 (CFHR3-1Δ), a likely causal variant measured using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, was tagged by rs6677604 in EA and AS and rs16840639 in AA, respectively. Deduced from genotypic associations of tag SNPs in EA, AA, and AS, homozygous deletion of CFHR3-1Δ (Pmeta = 3.2×10−7, OR = 1.47) conferred a higher risk of SLE than heterozygous deletion (Pmeta = 3.5×10−4, OR = 1.14). These results suggested that the CFHR3-1Δ deletion within the SLE-associated block, but not the previously described exonic SNPs of CFH, might contribute to the development of SLE in EA, AA, and AS, providing new insights into the role of complement regulators in the pathogenesis of SLE.

Introduction

SLE (OMIM 152700) is a debilitating autoimmune disease with strong genetic and environmental components, characterized by the production of autoantibodies resulting in tissue injury of multiple organs [1]. In SLE patients, aberrant complement activation leads to inflammatory injury [2], and fluctuation of serum C3 is a commonly used clinical biomarker of SLE disease activity [3]. In addition, a hereditary deficiency of C1q, C1r, C1s, C4 or C2 of the classical complement pathway impairs the clearance of immune complexes and debris from apoptotic cells, which strongly predisposes to SLE susceptibility [2]. Common variants of C3 and C4 have also been associated with risk of SLE [4], [5], [6]. Collectively, these findings indicate the important role of complement in the development of SLE.

Complement factor H (CFH), a key regulator of the alternative complement pathway, modulates the innate immune responses to microorganisms, controls C3 activation and prevents inflammatory injury to self tissue [7], [8]. CFH inhibits complement activation by preventing the formation and accelerating the decay of C3 convertase and acting as a cofactor for factor I-mediated degradation of C3b, both in plasma and on cell surfaces. Structurally, CFH contains 20 short consensus repeats (SCRs). SCR1-4 in the N-terminus mediate the cofactor/decay accelerating activity and SCR19-20 in the C-terminus are essential for cell surface regulation of CFH. In addition, CFH contains specific binding sites for polyanion (heparin or sialic acid), C-reactive protein (CRP) and microorganisms. CFH has five related proteins (CFHR1-5), all of which are also composed of SCRs [9]. SCRs in the N-terminus and C-terminus of CFHRs are highly homologous to SCR6-9 and SCR19-20 of CFH, respectively, suggesting that CFHRs and CFH may compete for binding to ligands. CFHRs lack SCRs homologous to SCR1-4 of CFH, and consequently do not exhibit cofactor/decay accelerating activity. Distinct from CFH, CFHR1 can inhibit C5 convertase activity and the formation of terminal membrane attack complex (MAC) [10]. A recent study has shown that CFH deficiency accelerates the development of lupus nephritis in lupus-prone mice MRL-lpr [11]. However, the role of CFHRs in the pathogenesis of SLE is still unknown.

CFH, CFHR3, CFHR1, CFHR4, CFHR2 and CFHR5, that present in tandem as a gene cluster located in human chromosome 1q32, are positional candidate genes within the 1q31-32 genomic region linked to SLE [12], [13]. In recent years, multiple exonic SNPs in CFH, such as I62V, Y402H, D936E and A473A, have been specifically associated with various human diseases including age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [14], [15], atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) [16] and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type II (MPGN II) [16], [17] as well as host susceptibility to meningococcal disease [18]. In addition, a common deletion of CFHR3 and CFHR1 (CFHR3-1Δ) has been associated with increased risk of aHUS [19] and decreased risk of AMD [20]. Taken together, these data prompted us to test whether genetic variants in CFH and CFHRs predisposed to SLE susceptibility.

Although recent genome wide association studies (GWAS) have b`n successfully used to identify SLE susceptibility genes [21], they still may be underpowered for specific genomic regions due to many factors such as sample size, marker density, ethnicity of subjects and over-stringent significance threshold. In these cases, a well-designed candidate gene-based association study can be used as a complementary approach to GWAS to identify genetic variants with modest effect size.

In this study, we fine mapped the CFH-CFHRs region using 60 SNPs and assessed their association with SLE susceptibility in a collection of 15,864 subjects (8,372 cases vs. 7,492 controls) from four ethnic groups. In addition, we assessed the association of CFHR3-1Δ with SLE by using tag SNPs.

Results

SNPs in the CFH-CFHRs region were associated with SLE susceptibility in European Americans and African Americans

To assess the association of CFH and CFHRs genes with SLE, we genotyped 60 tag SNPs covering the ∼360 kb CFH-CFHRs region in unrelated case-control subjects derived from four ethnic groups including European Americans (EA), African Americans (AA), Asians (AS), and Hispanics enriched for the Amerindian-European admixture (HS) (Figure 1A) (Table S1). According to the latest Hapmap CEU dataset (release 28), within the CFH-CFHRs region, 203 of 224 (90%) common SNPs (frequency>5%) could be captured by SNPs used in this study with r2>0.70. Within the most-studied gene CFH, previously identified disease-associated exonic SNPs including I62V (rs800292, typed), Y402H (tagged by rs7529589), D936E (tagged by rs10489456) and A474A (tagged by rs1410996) were evaluated for the association with SLE.

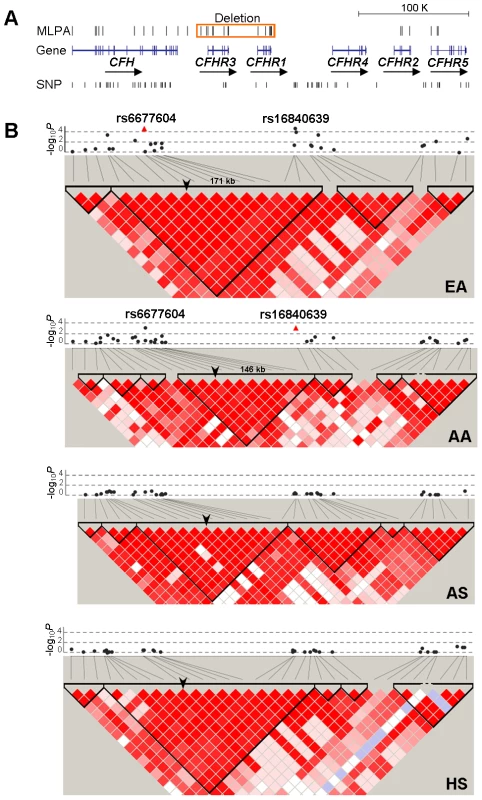

Fig. 1. Allelic association of SNPs in the CFH-CFHRs region with SLE and their LD patterns.

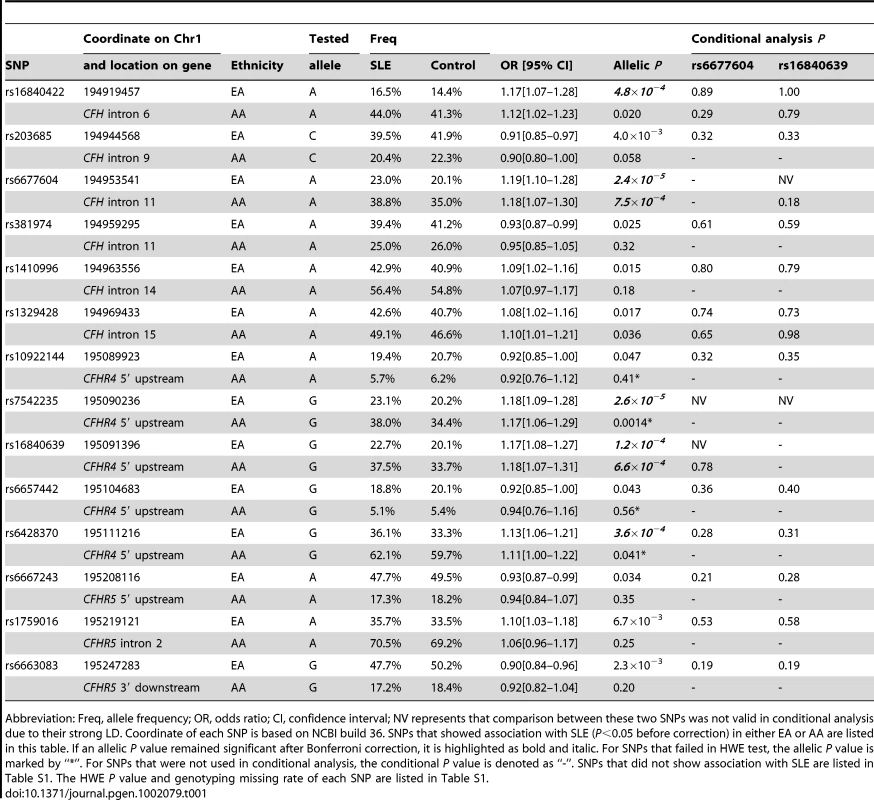

A) The genomic structure of the CFH-CFHRs region and the location of all SNP and MLPA markers are indicated. The deletion of CFHR3 and CFHR1 detected by MLPA markers is shown as a red box. B) The allelic P value of each SNP with SLE (−log10P) is plotted as a black circle according to its coordinate. The two SNPs exhibiting the strongest association with SLE in EA (rs6677604) and AA (rs16846039) are highlighted as red triangles. SNPs that failed in the HWE testing or showed low genotyping quality are not shown. SNP-constructed haplotype blocks were defined by Haploview using the confidence intervals model. An arrowhead is used to indicate the position of rs6677604 in the haplotype blocks. In the largest dataset (3,936 EA cases vs. 3,491 EA controls), after removing those failing the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) testing or showing low genotyping quality, fourteen SNPs were significantly associated with SLE (allelic P<0.05) (Table 1), of which rs6677604, located in intron 11 of CFH, exhibited the strongest association signal (minor allele frequency [MAF]: 23.0% in case vs. 20.1% in control, P = 2.4×10−5, OR[95%CI] = 1.19[1.10–1.28]). In the second largest dataset (1,679 AA cases vs. 1,934 AA controls), four SNPs were significantly associated with SLE (Table 1), all of which confirmed the association detected in EA, with rs16840639, located in the intergenic region between CFHR1 and CFHR4, showing the strongest association signal with a similar effect size (MAF: 37.5% vs. 33.7%, P = 6.6×10−4, OR[95%CI] = 1.18[1.07–1.31]). After Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, the association of rs6677604 and rs16840639 with SLE remained significant in both EA and AA (Table 1). However, in the two smaller datasets (1,265 AS cases vs. 1,260 AS controls and 1,492 HS cases vs. 807 HS controls), we failed to detect significant association of these SNPs with SLE (Table S1).

Tab. 1. Association of SNPs in the CFH-CFHRs region with SLE in European Americans and African Americans.

Abbreviation: Freq, allele frequency; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NV represents that comparison between these two SNPs was not valid in conditional analysis due to their strong LD. Coordinate of each SNP is based on NCBI build 36. SNPs that showed association with SLE (P<0.05 before correction) in either EA or AA are listed in this table. If an allelic P value remained significant after Bonferroni correction, it is highlighted as bold and italic. For SNPs that failed in HWE test, the allelic P value is marked by “*”. For SNPs that were not used in conditional analysis, the conditional P value is denoted as “-”. SNPs that did not show association with SLE are listed in Table S1. The HWE P value and genotyping missing rate of each SNP are listed in Table S1. Of note, we did not detect significant association of I62V, Y402H and D936E with SLE in any of the four datasets (Table S1). A474A was associated with risk of SLE in EA (P = 0.015 before correction, OR[95%CI] = 1.09[1.02–1.16]), but it was not confirmed in the other three ethnic groups (Table S1).

The causal variant could be localized to a ∼146 kb block and was tagged by the minor allele of rs6677604 and rs16840639

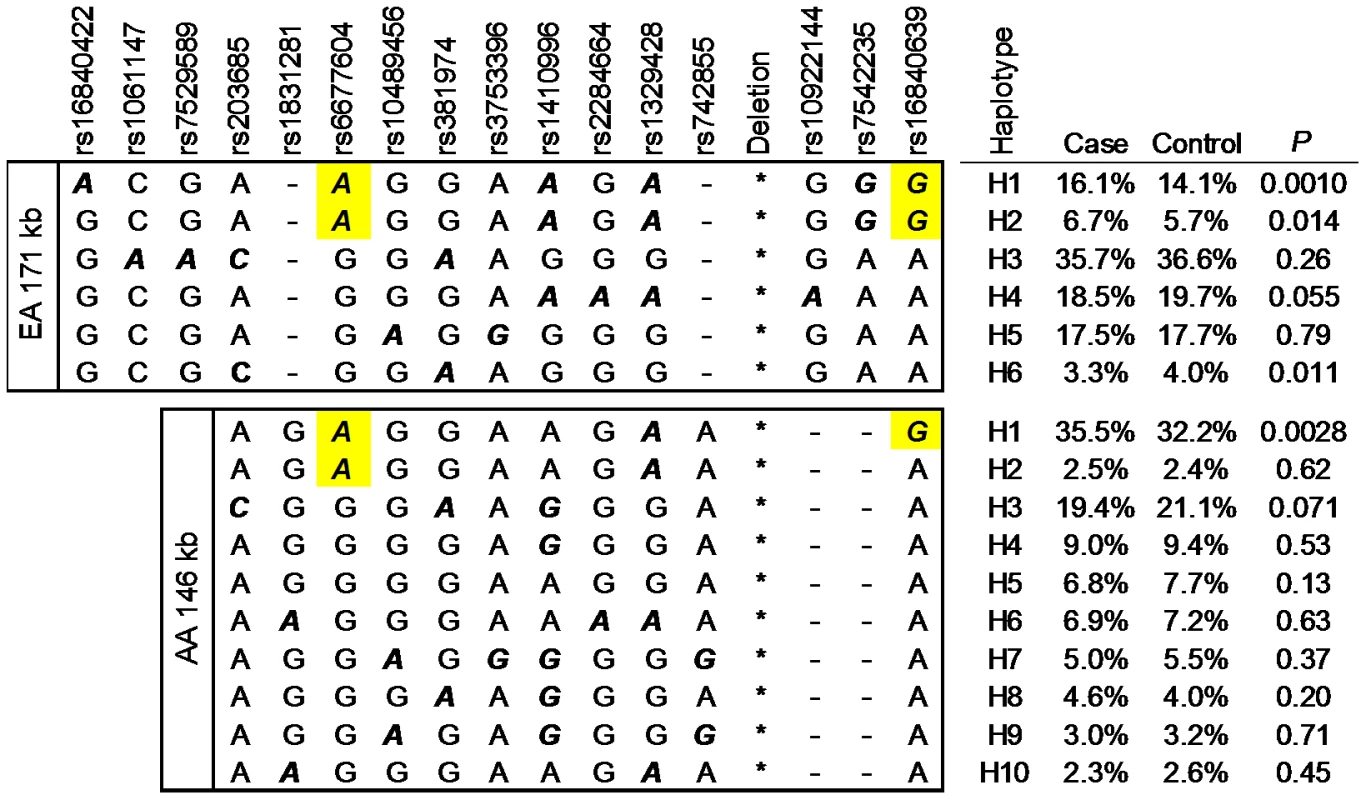

To localize the underlying causal variant, we compared all SLE-associated SNPs (P<0.05) identified in EA and AA and carried out linkage equilibrium (LD) analysis. Fourteen SNPs, spanning from intron 6 of CFH to the 3′ region downstream of CFHR5, were associated with SLE in EA. However, only 4 of 14 SNPs, spanning from intron 6 of CFH to the 5′ region upstream of CFHR4, showed consistent association with SLE in AA, suggesting a smaller SLE risk region. Of interest, within the risk region, rs6677604 and rs16840639 exhibited the strongest association with SLE in EA and AA, respectively. We found that rs6677604 and rs16840639 were in strong LD with each other in both EA (r2 = 0.96) and AA (r2 = 0.77). Haplotype analysis showed that rs6677604 and rs16840639 could be defined into a ∼171 kb block in EA and a smaller ∼146 kb block in AA, respectively (Figure 1B). The minor allele of rs6677604 or rs16840639 perfectly tagged two SLE risk haplotypes in EA (H1 : 16.1% vs. 14.1%, P = 0.0010; H2 : 6.7% vs. 5.7%, P = 0.014), and the minor allele of rs16840639 perfectly tagged the only risk haplotype in AA (H1 : 35.5% vs. 32.2%, P = 0.0028) (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. The minor allele of rs6677604 and rs16846039 tag risk haplotypes of SLE.

Haplotypes containing rs6677604 and rs16846039 (frequency>1%) are constructed in both EA and AA subjects, which correspond to the 2nd and the 4th block of EA and AA shown in Figure 1, respectively. SNPs not used to construct haplotypes are marked as “-”. The minor alleles of rs6677604 and rs16840639 are highlighted in a yellow box. The minor allele of each SNP is bolded and italicized. The position of CFHR3-1Δ is indicated as “*”. Using the conditional haplotype-based association test, we showed that after conditioning on rs6677604 or rs16840639 significant associations of all other SNPs were eliminated in both EA and AA (Table 1), which suggested that rs6677604 and rs16840639 could account for all association signals in the CFH-CFHRs region. Due to the strong LD between rs6677604 and rs16840639, the conditional test could not be applied to further distinguish their association signals.

To compare between rs6677604 and rs16840639, we combined their ORs detected in EA and AA to generate a meta-analysis P value. The combined P value of rs6677604 (Pmeta = 6.6×10−8, OR[95%CI] = 1.18[1.11–1.26]) was stronger than that of rs16840639 (Pmeta = 2.9×10−7, OR[95%CI] = 1.17[1.10–1.2]).

Taken together, these data suggested that the underlying causal variant of SLE was captured by two strongly SLE-associated SNPs rs6677604 and rs16840639 in this study, which might reside in a ∼146 kb block. Neither rs6677604 nor rs16840639 are located in genomic regions with known biological function, which prompted us to seek other likely causal variants within the SLE-associated block.

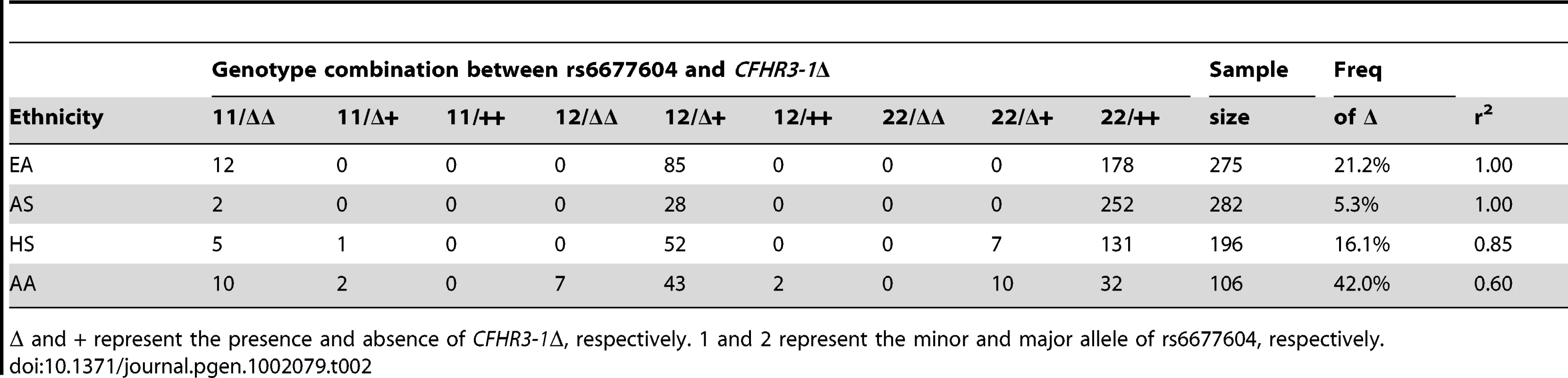

The CFHR3-1Δ deletion was tagged by the minor allele of rs6677604 and rs16840639

CFHR3-1Δ is a likely functional variant within the ∼146 kb SLE-associated block (as shown in Figure 1A and 1B), which results in the deletion of CFHR3 and CFHR1 and has been associated with AMD and aHUS [19], [20]. Because co-segregation of the CFHR3-1Δ deletion with the minor allele of rs6677604 in subjects with European Ancestry was observed in a previous study of AMD [20], we hypothesized that the association of CFHR3-1Δ with SLE was captured by SNPs in this study. Using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) (location of MLPA markers were shown in Figure 1A), we genotyped CFHR3-1Δ in 275 EA, 106 AA, 282 AS and 196 HS subjects, and then measured its LD with rs6677604. We found that CFHR3-1Δ and rs6677604 were in complete LD in EA (r2 = 1.00) and AS (r2 = 1.00), strong LD in HS (r2 = 0.85) and moderate LD in AA subjects (r2 = 0.60) (Table 2). In a subset of 58 unrelated AA subjects who were genotyped at both rs6677604 and rs16840639, we found that CFHR3-1Δ was in stronger LD with rs16840639 (r2 = 0.70) than with rs6677604 (r2 = 0.60). These results indicated that the association of the CFHR3-1Δ deletion with risk of SLE was tagged by the minor allele of rs6677604 in EA and rs16840639 in AA, respectively, suggesting that CFHR3-1Δ might be a risk variant for SLE.

Tab. 2. Pairwise LD between rs6677604 and CFHR3-1Δ in four ethnic groups.

Δ and + represent the presence and absence of CFHR3-1Δ, respectively. 1 and 2 represent the minor and major allele of rs6677604, respectively. We showed that rs6677604 and CFHR3-1Δ were in the same block in AS (Figure 1B), and the minor allele of rs6677604 could perfectly tag the CFHR3-1Δ deletion (r2 = 1.00). Thus, the lack of significant association of rs6677604 with SLE in our previous AS dataset might be due to insufficient statistical power. To increase power, we further genotyped 787 Chinese SLE cases and 1065 Chinese controls and then assessed the association of rs6677604 with SLE in an enlarged AS dataset (2052 cases vs. 2325 controls). In the enlarged AS dataset, we detected the significant association of rs6677604 with SLE (MAF: 7.1% vs. 6.1%, P = 0.0485, OR[95%CI] = 1.19[1.00–1.40]), supporting the hypothesis that CFHR3-1Δ might also be a risk variant for SLE in the AS population.

Tag SNPs suggested the CFHR3-1Δ deletion conferred a dosage-dependent risk effect of SLE

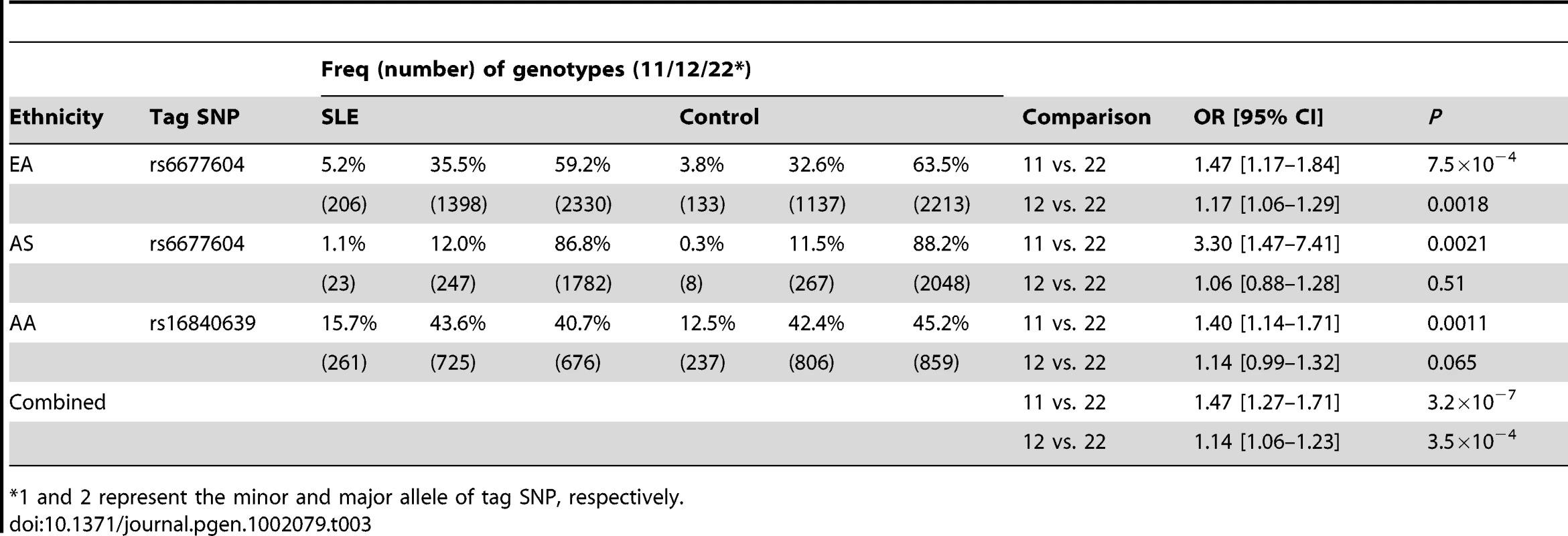

To test whether homozygous deletion of CFHR3-1Δ might confer a higher risk of SLE than heterozygous deletion, we compared the genotypic frequency of homozygous and heterozygous deletion to that of no deletion, respectively. In EA, using rs6677604 as a tag SNP, we found that the homozygous deletion of CFHR3-1Δ conferred a significantly increased risk of SLE (P = 7.5×10−4, OR[95%CI] = 1.47[1.17–1.84]) compared to no deletion, which was stronger than that of the heterozygous deletion (P = 0.0018, OR[95%CI] = 1.17[1.06–1.29]) (Table 3), suggesting a dosage dependent risk effect of the CFHR3-1Δ deletion. To confirm, we compared genotypic associations of CFHR3-1Δ in AS and AA using rs6677604 and rs16840639 as tag SNPs, respectively. In these two ethnic groups, we found that only homozygous deletion of CFHR3-1Δ conferred a significantly increased risk of SLE compared to no deletion (AS: P = 0.0021, OR[95%CI] = 3.30[1.47–7.41]; AA: P = 0.0011, OR[95%CI] = 1.40[1.14–1.71]) (Table 3), supporting the hypothesis that homozygous deletion of CFHR3-1Δ conferred a higher risk of SLE than heterozygous deletion. In a meta-analysis combining ORs of EA, AA and AS, we confirmed that the homozygous deletion of CFHR3-1Δ (Pmeta = 3.2×10−7, OR[95%CI] = 1.47[1.27–1.71]) had a stronger association with risk of SLE than the heterozygous deletion (Pmeta = 3.5×10−4, OR[95%CI] = 1.14[1.06–1.23]).

Tab. 3. Dosage-dependent risk effect of the CFHR3-1Δ deletion.

*1 and 2 represent the minor and major allele of tag SNP, respectively. Tag SNPs suggested that CFHR3-1Δ was associated with SLE but not specific clinical manifestations preferentially

SLE is a complex disease with heterogeneous sub-phenotypes. To determine whether CFHR3-1Δ had a stronger association with specific clinical manifestations of SLE, we compared its frequency in SLE cases stratified by the presence or absence of each of the eleven ACR classification criteria (malar rash, discoid rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, arthritis, serositis, renal disorder, neurologic disorder, hematologic disorder, immunologic disorder and antinuclear antibody) and five autoantibodies (anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm, anti-RNP, anti-SSA/Ro and anti-SSB/La). In EA, we found that tag SNP rs6677604 of CFHR3-1Δ was associated with the absence of neurologic disorder (Table S2). However, in AA, we found that the corresponding tag SNP rs16840639 was associated with the absence of anti-dsDNA and the presence of serositis (Table S2), the latter of which was found not to be significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Insufficient clinical information for the majority of AS SLE patients precluded us from conducting these analyses. Taken together, these data did not provide evidence for a stronger association of CFHR3-1Δ with specific clinical manifestations of SLE.

Discussion

In this study, we identified SLE-associated SNPs in the CFH-CFHRs region in three ethnic groups consisting of EA, AA and AS. In addition, we showed that the underlying causal variant was captured by rs6677104 and rs16840639 and could be localized to a ∼146 kb block extending from intron 9 of CFH to the 5′ region upstream of CFHR4. We demonstrated that the CFHR3-1Δ deletion, which has been associated with AMD and aHUS, could be tagged by the minor risk alleles of rs6677604 (r2 = 1.00 in EA and AS) and rs16840639 (r2 = 0.70 in AA) and showed dosage-dependent association with risk of SLE. These data strongly suggested that CFHR3-1Δ, which leads to reduced levels of CFHR3 and CFHR1 proteins, was the causal variant for increased risk of SLE within the SLE-associated block.

Multiple CFH exonic SNPs have been associated with various human diseases, but none of them were associated with SLE in this study. Y402H (rs1061170) is the most studied non-synonymous SNP of CFH. Y402H is located in SCR7 and affects the binding of CFH with glycosaminoglycans and CRP [22], [23], [24]. Y402H has been strongly associated with risk of AMD and MGPN2 but not associated with aHUS [16]. In this study, we genotyped a tag SNP of Y402H (rs7529589, r2 = 0.75 with Y402H according to HapMap CEU data) and detected no statistically significant association with SLE (Table S1). In a previous study, we had genotyped Y402H directly in 2033 EA cases and 2824 EA controls, and observed a similar result (37.4% vs. 37.7%, P = 0.81, OR = 0.99). I62V (rs800292) located in the N-terminal SCR2 is another well-studied non-synonymous SNP of CFH. Although I62V may result in increased binding of CFH with C3b and enhanced CFH co-factor activity and has been associated with decreased risk of AMD, MPGN II and aHUS [16], [25], it was not associated with SLE in this study (Table S1). D936E (rs1065489 in SCR16) was associated with lower host susceptibility to meningococcal disease in a recent GWAS [18]. We genotyped a perfect tag SNP (rs10489456) of D936E and failed to detect an association with SLE (Table S1). A synonymous SNP A474A (rs2274700 in SCR8) and its tag SNP rs1410996 were strongly associated with risk of AMD independent of Y402H [26], [27], but we detected only a marginal association between rs1410996 and risk of SLE in EA (Table 1), which was eliminated after conditioning on rs6677604 or rs16840639. In addition, two synonymous SNPs A307A (rs1061147 in SCR5) and Q672Q (rs3753396 in SCR13) that are in strong LD with Y402H and D936E, respectively, were not associated with SLE in our study. These data suggest that the previously described disease-associated CFH exonic SNPs do not contribute to the development of SLE.

Compared with SNP genotyping assays, genotyping assays for copy number variation are more labor-intensive and costly. Consequently, CFHR3-1Δ was not specifically genotyped in this study to assess its association with SLE. Instead, we evaluated the effect of the CFHR3-1Δ deletion on SLE development indirectly using tag SNPs that were in strong LD with it. We first confirmed that CFHR3-1Δ was in strong LD with rs6677604 in EA, similar to previous studies of AMD [20], [28]. Furthermore, we showed that CFHR3-1Δ was also in strong LD with rs6677604 in AS and HS. In addition, we found that CFHR3-1Δ was in stronger LD with rs16840639 than with rs6677604 in AA. Of note, in AA, the most significant association with SLE was detected at rs16840639 rather than rs6677604, and the risk haplotype H1 in AA was perfectly tagged by the minor allele of rs16840639 rather than rs6677604 (Figure 2), suggesting that rs16840639 captured the underlying causal variant CFHR3-1Δ in AA. Using these tag SNPs, we deduced that homozygous CFHR3-1Δ deletion conferred higher risk of SLE than heterozygous deletion, which suggested a change in gene dosage of the encoded proteins CFHR3 and CFHR1 might account for the increased SLE risk.

The CFHR3-1Δ deletion was associated with the general phenotype of SLE but did not consistently exhibit stronger signals to a specific clinical manifestation in EA and AA, and was not specifically associated with the presence of renal disorder. This is in contrast to the effect of CFH deficiency, which results in the development of glomerulonephritis in CFH knockout mice due to uncontrolled C3 activation [11], [29]. In addition, the absence of CFH in plasma causes human MPGN II [30], but an association of the CFHR3-1Δ deletion with MPGN II has not been reported. The absence of an association of CFHR3-1Δ with renal disorder in lupus suggests that CFHR3 and CFHR1 play a different role from CFH in the pathogenesis of lupus, although further studies are required to validate the lack of association between the CFHR3-1Δ deletion and renal disorder in SLE.

The CFHR3-1Δ deletion has opposite effects in different diseases [9], and the underlying mechanism is poorly understood. Activated complement pathways converge to generate C5 convertase, which cleaves C5 into C5a and C5b. C5a is a potent chemoattractant. C5b initiates the formation of the terminal MAC. CFHR1 acts as a complement regulator to inhibit C5 convertase activity and terminal MAC formation [10], and CFHR3 displays anti-inflammatory effects by blocking C5a generation and C5a-mediated chemoattraction of neutrophils [31]. Increased neutrophils lead to inflammatory injuries in many non-infectious human diseases [32]. It has been shown that immune complex-induced inflammatory injuries are largely mediated by C5a receptor and blocking C5a receptor reduces manifestation of lupus nephritis in mice [33], [34]. In addition, increased apoptotic neutrophils contribute to autoantigen excess and have been associated with increased disease activity in SLE [35]. The CFHR3-1Δ deletion results in decreased CFHR3 and CFHR1 levels and may therefore lead to uncontrolled production of chemoattractant C5a predisposing to SLE. Of interest, the CFHR3-1Δ deletion also has a risk effect in aHUS and the CFHR3 and CFHR1 deficiency in plasma has been associated with the presence of anti-CFH autoantibodies, which bind to the C-terminus of CFH and block CFH binding to cell surfaces [36], [37]. It is also possible that CFHR3-1Δ is also associated with the presence of anti-CFH autoantibodies in SLE and thus leads to impaired CFH cell surface regulation.

Both CFHR3 and CFHR1, lacking the CFH N-terminus regulatory activity, were reported to compete with CFH for binding to C3b, and thus CFHR3 and CFHR1 deficiency may lead to enhanced CFH regulation [31], which may explain the protective effect of the CFHR3-1Δ deletion in AMD. Of interest, as mentioned before, the non-synonymous SNP I62V in the CFH regulatory domain may also increase CFH regulation. I62V confers a protective effect in AMD, aHUS and MPGN II [16], but it was not associated with SLE in this study.

Statistical under-powering might account for the failure to detect a significant association in HS dataset. First, rs6677604 and CFHR3-1Δ were in strong LD and could be defined into a block in HS, which excluded the possibility that the CFHR3-1Δ deletion was not tagged in the HS dataset. In addition, there was no genetic heterogeneity of rs6677604 in the four ethnic groups (P = 0.76), in which the risk minor allele showed consistently higher frequency in cases than in controls. Finally, based on rs6677604, post hoc analysis indicated a much lower power of 51% in HS to detect association with SLE (P<0.05) than the power of 98% in EA and 92% in AA. Thus, the association of CFHR3-1Δ with SLE in HS needs to be further evaluated in a larger dataset.

One limitation of this study is that we have not addressed whether rare variants in the CFH-CFHRs region may contribute to the development of SLE. Pathogenic rare variants clustering in CFH C-terminus affect CFH cell surface binding, but they were only found in aHUS patients, not in AMD, MPGN II patients and healthy controls [16]. Deep sequencing of exons in CFH C-terminus in patients with SLE may elucidate whether these rare variants are associated with SLE.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to show that genetic variants in the CFH-CFHRs region are associated with SLE susceptibility. Our consistent observations of dose-dependent association between CFHR3-1Δ and SLE across three distinct ancestral populations and no association in CFH exonic SNPs suggest a novel role for CFHR3 and CFHR1 in the pathogenesis of SLE. Further functional studies are required to elucidate the underlying mechanism of CFHR3-1Δ.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Human Subject Institutional Review Boards or the ethnic committees of each institution. All subjects were enrolled after informed consent had been obtained.

Subject collection

To test the association of CFH and CFHRs with SLE, we used a large collection of samples from case-control subjects from multiple ethnic groups. These samples were from the collaborative Large Lupus Association Study 2 (LLAS2) and were contributed by participating institutions in the United States, Asia and Europe. According to genetic ancestry, subjects were grouped into four ethnic groups including European American (3,936 cases vs. 3,491 controls), African American (1,679 cases vs. 1,934 controls), Asian (1,265 cases vs. 1,260 controls) and Hispanic enriched for the Amerindian-European admixture (1,492 cases vs. 807 controls). Asians were comprised of Koreans (884 cases vs. 994 controls), Chinese (200 cases vs. 205 controls) and subjects from other East Asian countries such as Japan and Singapore (181 cases vs. 61 controls). African Americans included 275 Gullahs (152 cases vs. 123 controls), who are subjects with African Ancestry.

To test LD between CFHR3-1Δ and SLE-associated SNPs, we used 275 unrelated European Americans (187 cases vs. 88 controls), 106 African Americans (88 unrelated subjects [58 cases vs. 30 controls] and 18 subjects from 6 SLE trios families), 282 unrelated Chinese (218 cases vs. 64 controls) and 196 Hispanics (157 unrelated subjects [91 cases vs. 66 controls] and 39 subjects from 13 SLE trios families). All of these subjects were enrolled from UCLA.

To enlarge the sample size of Asians for association test, we used 1,852 Chinese case-control subjects (787 vs. 1065) recruited from Shanghai Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

All SLE patients met the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for the classification of SLE [38].

SNP genotyping and data cleaning

LLAS2 samples were processed at the Lupus Genetics Studies Unit of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF). SNP genotyping was carried out on the Illumina iSelect platform. Subjects with individual genotyping call rate <0.90 were removed because of low data quality. Subjects that were duplicated or first degree related were also removed. Both principal component analysis and global ancestry estimation based on 347 ancestry informative markers were used to detect population stratification and admixture, as described in another LLAS2 report [39]. After removing genetic outliers, a final dataset of 15,864 unrelated subjects (8,372 cases vs. 7,492 controls) was obtained.

Taqman SNP genotyping assay (Applied Biosystems, California, USA) was used to genotype rs6677604 for subjects who were not recruited into LLAS2.

MLPA genotyping

MLPA kit “SALSA MLPA KIT P236-A1 ARMD mix-1” was used to genotype the CFH-CFHRs region according to the manufacture's instruction (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). ABI 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) was used to run gel electrophoresis. Software Peak Scanner v1.0 (Applied Biosystems) was used to extract peaks generated in electrophoresis. Coffalyser v9.4 (MRC-Holland) was used to readout copy number of target region.

Statistical analysis

The HWE test threshold was set at P>0.01 for controls and P>0.0001 for cases. SNPs failing the HWE test were excluded from association test. SNPs showing genotyping missing rate>5% or showing significantly different genotyping missing rate between cases and controls (missing rate>2% and Pmissing<0.05) were also excluded from association test. In allelic association test (Pearson's χ2–test), the significance level was set at P<0.05. Haploview 4.2 was used to estimate pairwise LD values between SNPs, define haplotypes blocks and calculate haplotypic association with SLE. Haplotype-based conditional association analysis was carried out by Plink v1.07. Mantel-Haenszel analysis was performed to generate the meta-analysis P value. CaTS was used to calculate statistical power.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. RahmanAIsenbergDA 2008 Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 358 929 939

2. MandersonAPBottoMWalportMJ 2004 The role of complement in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. Annu Rev Immunol 22 431 456

3. BirminghamDJIrshaidFNagarajaHNZouXTsaoBP 2010 The complex nature of serum C3 and C4 as biomarkers of lupus renal flare. Lupus 19 1272 1280

4. MiyagawaHYamaiMSakaguchiDKiyoharaCTsukamotoH 2008 Association of polymorphisms in complement component C3 gene with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47 158 164

5. RhodesBHunnangkulSMorrisDLHsaioLCGrahamDS 2009 The heritability and genetics of complement C3 expression in UK SLE families. Genes Immun 10 525 530

6. YangYChungEKWuYLSavelliSLNagarajaHN 2007 Gene copy-number variation and associated polymorphisms of complement component C4 in human systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): low copy number is a risk factor for and high copy number is a protective factor against SLE susceptibility in European Americans. Am J Hum Genet 80 1037 1054

7. de CordobaSRde JorgeEG 2008 Translational mini-review series on complement factor H: genetics and disease associations of human complement factor H. Clin Exp Immunol 151 1 13

8. Rodriguez de CordobaSEsparza-GordilloJGoicoechea de JorgeELopez-TrascasaMSanchez-CorralP 2004 The human complement factor H: functional roles, genetic variations and disease associations. Mol Immunol 41 355 367

9. JozsiMZipfelPF 2008 Factor H family proteins and human diseases. Trends Immunol 29 380 387

10. HeinenSHartmannALauerNWiehlUDahseHM 2009 Factor H-related protein 1 (CFHR-1) inhibits complement C5 convertase activity and terminal complex formation. Blood 114 2439 2447

11. BaoLHaasMQuiggRJ 2011 Complement factor H deficiency accelerates development of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 22 285 295

12. JohannesonBLimaGvon SalomeJAlarcon-SegoviaDAlarcon-RiquelmeME 2002 A major susceptibility locus for systemic lupus erythemathosus maps to chromosome 1q31. Am J Hum Genet 71 1060 1071

13. WuHBoackleSAHanvivadhanakulPUlgiatiDGrossmanJM 2007 Association of a common complement receptor 2 haplotype with increased risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 3961 3966

14. HagemanGSAndersonDHJohnsonLVHancoxLSTaiberAJ 2005 A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 7227 7232

15. KleinRJZeissCChewEYTsaiJYSacklerRS 2005 Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science 308 385 389

16. PickeringMCde JorgeEGMartinez-BarricarteRRecaldeSGarcia-LayanaA 2007 Spontaneous hemolytic uremic syndrome triggered by complement factor H lacking surface recognition domains. J Exp Med 204 1249 1256

17. Abrera-AbeledaMANishimuraCSmithJLSethiSMcRaeJL 2006 Variations in the complement regulatory genes factor H (CFH) and factor H related 5 (CFHR5) are associated with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type II (dense deposit disease). J Med Genet 43 582 589

18. DavilaSWrightVJKhorCCSimKSBinderA 2010 Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the CFH region associated with host susceptibility to meningococcal disease. Nat Genet 42 772 776

19. ZipfelPFEdeyMHeinenSJozsiMRichterH 2007 Deletion of complement factor H-related genes CFHR1 and CFHR3 is associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. PLoS Genet 3 e41 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030041

20. HughesAEOrrNEsfandiaryHDiaz-TorresMGoodshipT 2006 A common CFH haplotype, with deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3, is associated with lower risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 38 1173 1177

21. DengYTsaoBP 2010 Genetic susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in the genomic era. Nat Rev Rheumatol 6 683 692

22. ClarkSJHigmanVAMulloyBPerkinsSJLeaSM 2006 His-384 allotypic variant of factor H associated with age-related macular degeneration has different heparin binding properties from the non-disease-associated form. J Biol Chem 281 24713 24720

23. ProsserBEJohnsonSRoversiPHerbertAPBlaumBS 2007 Structural basis for complement factor H linked age-related macular degeneration. J Exp Med 204 2277 2283

24. SkerkaCLauerNWeinbergerAAKeilhauerCNSuhnelJ 2007 Defective complement control of factor H (Y402H) and FHL-1 in age-related macular degeneration. Mol Immunol 44 3398 3406

25. TortajadaAMontesTMartinez-BarricarteRMorganBPHarrisCL 2009 The disease-protective complement factor H allotypic variant Ile62 shows increased binding affinity for C3b and enhanced cofactor activity. Hum Mol Genet 18 3452 3461

26. LiMAtmaca-SonmezPOthmanMBranhamKEKhannaR 2006 CFH haplotypes without the Y402H coding variant show strong association with susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 38 1049 1054

27. MallerJGeorgeSPurcellSFagernessJAltshulerD 2006 Common variation in three genes, including a noncoding variant in CFH, strongly influences risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 38 1055 1059

28. SpencerKLHauserMAOlsonLMSchmidtSScottWK 2008 Deletion of CFHR3 and CFHR1 genes in age-related macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 17 971 977

29. PickeringMCCookHTWarrenJBygraveAEMossJ 2002 Uncontrolled C3 activation causes membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in mice deficient in complement factor H. Nat Genet 31 424 428

30. AppelGBCookHTHagemanGJennetteJCKashgarianM 2005 Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type II (dense deposit disease): an update. J Am Soc Nephrol 16 1392 1403

31. FritscheLGLauerNHartmannAStippaSKeilhauerCN 2010 An imbalance of human complement regulatory proteins CFHR1, CFHR3 and factor H influences risk for age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Hum Mol Genet 19 4694 4704

32. DallegriFOttonelloL 1997 Tissue injury in neutrophilic inflammation. Inflamm Res 46 382 391

33. BaoLOsaweIPuriTLambrisJDHaasM 2005 C5a promotes development of experimental lupus nephritis which can be blocked with a specific receptor antagonist. Eur J Immunol 35 2496 2506

34. BaumannUChouchakovaNGeweckeBKohlJCarrollMC 2001 Distinct tissue site-specific requirements of mast cells and complement components C3/C5a receptor in IgG immune complex-induced injury of skin and lung. J Immunol 167 1022 1027

35. CourtneyPACrockardADWilliamsonKIrvineAEKennedyRJ 1999 Increased apoptotic peripheral blood neutrophils in systemic lupus erythematosus: relations with disease activity, antibodies to double stranded DNA, and neutropenia. Ann Rheum Dis 58 309 314

36. Dragon-DureyMALoiratCCloarecSMacherMABlouinJ 2005 Anti-Factor H autoantibodies associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 16 555 563

37. JozsiMStrobelSDahseHMLiuWSHoyerPF 2007 Anti factor H autoantibodies block C-terminal recognition function of factor H in hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood 110 1516 1518

38. HochbergMC 1997 Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 40 1725

39. LessardCJAdriantoIKellyJAKaufmanKMGrundahlKM 2011 Identification of a systemic lupus erythematosus susceptibility locus at 11p13 between PDHX and CD44 in a multiethnic study. Am J Hum Genet 88 83 91

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 5- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Structural and Functional Differences in the Long Non-Coding RNA in Mouse and Human

- Identification, Replication, and Functional Fine-Mapping of Expression Quantitative Trait Loci in Primary Human Liver Tissue

- A −436C>A Polymorphism in the Human Gene Promoter Associated with Severe Childhood Malaria

- A Decline in p38 MAPK Signaling Underlies Immunosenescence in

- The Operon Balances the Requirements for Vegetative Stability and Conjugative Transfer of Plasmid R388

- Novel and Conserved Protein Macoilin Is Required for Diverse Neuronal Functions in

- Ixr1 Is Required for the Expression of the Ribonucleotide Reductase Rnr1 and Maintenance of dNTP Pools

- Genome of Strain SmR1, a Specialized Diazotrophic Endophyte of Tropical Grasses

- A Deficiency of Ceramide Biosynthesis Causes Cerebellar Purkinje Cell Neurodegeneration and Lipofuscin Accumulation

- A Latent Pro-Survival Function for the Mir-290-295 Cluster in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Association of Genetic Variants in Complement Factor H and Factor H-Related Genes with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Susceptibility

- DNA Methylation Dynamics in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells over Time

- Prion Formation and Polyglutamine Aggregation Are Controlled by Two Classes of Genes

- Integrated Genome-Scale Prediction of Detrimental Mutations in Transcription Networks

- Post-Embryonic Nerve-Associated Precursors to Adult Pigment Cells: Genetic Requirements and Dynamics of Morphogenesis and Differentiation

- A Novel Mouse Synaptonemal Complex Protein Is Essential for Loading of Central Element Proteins, Recombination, and Fertility

- STAT Is an Essential Activator of the Zygotic Genome in the Early Embryo

- A Genetic and Structural Study of Genome Rearrangements Mediated by High Copy Repeat Ty1 Elements

- A Missense Mutation in Causes a Major QTL Effect on Ear Size in Pigs

- A Flurry of Folding Problems: An Interview with Susan Lindquist

- Meiotic Recombination Intermediates Are Resolved with Minimal Crossover Formation during Return-to-Growth, an Analogue of the Mitotic Cell Cycle

- A Nervous Origin for Fish Stripes

- The ISWI Chromatin Remodeler Organizes the hsrω ncRNA–Containing Omega Speckle Nuclear Compartments

- The Telomerase Subunit Est3 Binds Telomeres in a Cell Cycle– and Est1–Dependent Manner and Interacts Directly with Est1

- Nodal-Dependent Mesendoderm Specification Requires the Combinatorial Activities of FoxH1 and Eomesodermin

- SHINE Transcription Factors Act Redundantly to Pattern the Archetypal Surface of Arabidopsis Flower Organs

- Characterizing Genetic Risk at Known Prostate Cancer Susceptibility Loci in African Americans

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Nodal-Dependent Mesendoderm Specification Requires the Combinatorial Activities of FoxH1 and Eomesodermin

- SHINE Transcription Factors Act Redundantly to Pattern the Archetypal Surface of Arabidopsis Flower Organs

- Association of Genetic Variants in Complement Factor H and Factor H-Related Genes with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Susceptibility

- STAT Is an Essential Activator of the Zygotic Genome in the Early Embryo

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání