-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Emergence of Azole-Resistant Strains due to Agricultural Azole Use Creates an Increasing Threat to Human Health

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 9(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003633

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003633Summary

article has not abstract

Aspergillus fumigatus, a ubiquitously distributed opportunistic pathogen, is the global leading cause of aspergillosis and causes one of the highest numbers of deaths among patients with fungal infections [1]. Invasive aspergillosis is the most severe manifestation with an overall annual incidence up to 10% in immunosuppressed patients, whereas chronic pulmonary aspergillosis affects about 3 million, primarily immunocompetent, individuals each year [2]. Three triazole antifungals, namely itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole, are recommended first-line drugs in the treatment and prophylaxis of aspergillosis [3]. However, azole resistance in A. fumigatus isolates is increasingly reported with variable prevalence in Europe, the United States, South America, China, Japan, Iran, and India [4]–[9]. For example, about 10% of strains of A. fumigatus from the Netherlands are itraconazole resistant, and in the United Kingdom, the frequency increased from 0%–5% during 2002–2004 to 17%–20% in 2007–2009 [10]–[13]. In the ARTEMIS global surveillance program involving 62 medical centers, 5.8% of A. fumigatus strains showed elevated MICs to one or more triazoles [5]. Similarly, the prospective SCARE (Surveillance Collaboration on Aspergillus Resistance in Europe) study involving 22 medical centers in 19 countries identified an overall prevalence of 3.4% azole resistance. Azole-resistant A. fumigatus (ARAF) ranged from 0% to 26% among the 22 centres and was detected in 11 (57.9%) of the 19 participating European countries [4 and P.E. Verweij, personal communication]. Interestingly, almost half (48.9%) of the ARAF isolates from the SCARE network in European countries were resistant to multiple azoles and harbored the TR34/L98H mutation in the cyp51A gene [4 and P.E. Verweij, personal communication]. Indeed, multi-azole resistance in A. fumigatus due to the TR34/L98H mutations has become an emerging problem in both Europe and Asia and has been associated with high rates of treatment failures [12]–[14].

Azole antifungal drugs inhibit the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, specifically the cytochrome p450 sterol 14-α-demethylase encoded by the cyp51A gene, which leads to depletion of ergosterol and accumulation of toxic sterols. The majority of ARAF isolates contain alterations in the target enzyme and the mutated target showed reduced or no binding to the drugs [15]. While most mutations in ARAF isolates were single nucleotide substitutions in the target gene (cyp51A), mutations at other genes such as the cdr1B have also been reported. For example, in the United Kingdom the frequency of ARAF isolates without cyp51A mutations has been reported to be more than 50% [16].

Routes of Azole Resistance Development

The epidemiologic data on azole resistance is mainly from two clinical entities. One group comprises noninvasive diseases including patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), aspergilloma, and chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) who were treated with long-term azole therapy (mainly itraconazole) and developed acquired resistance after 1–30 months of treatment [13]. In these patients, the ARAF isolates may be resistant to only itraconazole or exhibit a multi-azole-resistant phenotype. The underlying resistance mechanism commonly involves point mutations in the cyp51A gene, indicating that in patients exposed to long-term azole therapy, the fungus is capable of rapidly adapting to azole drug(s) [11]–[14]. The genotypic analysis of serial isolates of A. fumigatus from patients with chronic aspergillosis revealed that the initial susceptible and later resistant isolates had the same genotype. The only changes were the specific mutations conferring azole resistance, consistent with the development of resistance arising from azole therapy [13].

The second group of patients with ARAF are those with acute aspergillosis but with no known prior exposure to azole drugs [12]. In contrast to the first group in which de novo mutation of the fungus in cavitary lesions is the primary mechanism for the development of azole resistance, those of the second group likely acquired ARAF strains from external environments. In fact 50% of the patients with invasive aspergillosis due to ARAF are known to be azole naïve and the outcome of patients with azole-resistant invasive aspergillosis has been dismal, with a mortality rate of 88% [12]. Eighty percent of the ARAF strains from patients with invasive aspergillosis described in the SCARE network had the TR34/L98H mutations, which consist of a substitution of leucine to histidine at codon 98 of the cyp51A gene in combination with a 34-bp tandem repeat in the promoter region. These mutations enabled resistance to itraconazole and intermediate susceptibility or resistance to voriconazole, posaconazole, or both [4], [17], [18]. As described above, although the environmentally derived azole-resistant strains are predominately associated with acute invasive infections [12], [19], the same mechanism has also been reported in patients with chronic and allergic pulmonary infections [20]. For example, Denning et al. detected TR34/L98H and M220 mutations in 55.1% respiratory samples of CPA and ABPA patients by direct PCR and some of these patients had no prior azole therapy [20].

Environmentally Mediated Development of Azole Resistance

Several recent findings support the hypothesis that ARAF strains in patients with invasive aspergillosis were more likely to be acquired from environmental sources rather than from de novo mutation and selection within patients during azole therapy. First, ARAF strains have been found in patients who had never been treated with azole antifungal drugs [7], [12]–[14]. Second, ARAF strains have been found in many environmental niches including flowerbeds, compost, leaves, plant seeds, soil samples of tea gardens, paddy fields, hospital surroundings, and aerial samples of hospitals [19], [21]–[23]. The majority of the environmental ARAF isolates harbor the TR34/L98H mutations at the cyp51A gene [19], [21]–[23]. ARAF isolates with the TR34/L98H mutations have been detected in the environment of the Netherlands, Denmark, India, and Iran [19], [21]–[23]. It is noteworthy that environmental surveys of ARAF from Europe reported that 12% of Dutch soil samples and 8% of Danish soil samples had the TR34/L98H genotype [19], [22]. Similarly, environmental surveys across India detected that 7% of all A. fumigatus isolates and 5% of soil/aerial samples carried the TR34/L98H mutation [21]. These strains showed cross-resistance to voriconazole, posaconazole, itraconazole, and to six triazole fungicides used extensively in agriculture [21].

Recently, another mutation of the cyp51A gene (TR46/Y121F/T289A) was reported in ARAF isolates from 15 patients in six hospitals in the Netherlands [24]. Interestingly, isolates with the same TR46/Y121F/T289A mutations were also recovered from patients' homes and backyards [24]. Apart from the Netherlands, clinical and environmental strains of A. fumigatus carrying the TR46/Y121F/T289A mutations have also been identified in neighboring Belgium [25] and in India [26]. As most patients acquire A. fumigatus from the environment, the emergence and spread of azole-resistant strains in the environment will put more humans at risk, especially those with compromised immunity.

Linking Clinical Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus to Fungicide Usage in Agriculture

The hypothesis that clinical azole resistance in A. fumigatus is related to the use of fungicides in agriculture was first proposed by investigators from the Netherlands [19]. The resistant genotype TR34/L98H was found in 90% of ARAF isolates obtained from azole-naïve patients [11] and they hypothesized that if strains of A. fumigatus received sufficient azole challenge in the environment through nonmedical application of azole compounds, azole-resistant strains would be selected and spread [27]. Demethylase inhibitors (DMIs) including azole fungicides are commonly used for crop protection and for the preservation of a variety of materials such as wood [27]. For example, azole fungicides are broadly used to control mildews and rusts of grains, fruits, vegetables, and ornamentals; powdery mildew in cereals, berry fruits, vines, and tomatoes; and several other plant pathogenic fungi. Over one-third of total fungicide sales are azoles (mostly triazoles) and over 99% of the DMIs are used in agriculture. In addition, there are over 25 types of azole DMIs for agricultural uses, far more than the three licensed medical triazoles for the treatment of aspergillosis. Furthermore, the azoles could persist and remain active in many ecological niches such as agricultural soil and aquatic environments for several months.

The widespread application of triazole fungicides and their persistence in the environment are significant selective forces for the emergence and spread of ARAF. These environmental triazoles can reduce the population of azole-susceptible strains and selecting for azole-resistant genotypes [27]. Intensive use of DMI fungicides for post-harvest spoilage crop protection against phytopathogenic molds is known to cause the development of resistance in many fungi of agricultural importance. For example, resistance or tolerance to triazole fungicides has been reported for important crop pathogens such as Mycosphaerella graminicola (wheat), Rhynchosporium secalis (barley), and Botrytis cinerea (strawberry) [28]. Since A. fumigatus shares its natural environments with many fungal plant pathogens, strains of A. fumigatus are also exposed to the same strong and persistent pressure from fungicides. Indeed, the presence of a tandem repeat at the 5′-end upstream of the 14-α-demethylase gene is an important mechanism found in many plant pathogenic molds resistant to sterol DMI fungicides [19].

All A. fumigatus isolates with the TR34/L98H mutations from both clinical and environmental origins have shown cross-resistance to not only all three medical triazoles, but also five agricultural triazole DMI fungicides: propiconazole, bromuconazole, tebuconazole, epoxiconazole, and difenoconazole [21], [29]. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that exposure of A. fumigatus to azole fungicides in the environment causes cross-resistance to medical triazoles. By molecular modeling studies, these five triazole DMI fungicides were found to have similar molecular structures as medical triazoles (Figure 1) and they all adopt a similar conformation while docking the target enzyme in susceptible strains of A. fumigatus [15], [29]. However, there was limited docking and activity against ARAF strains with the TR34/L98H mutation [29]. A similar phenomenon was also observed in the maize anthracnose fungus Colletotrichum graminicola. Strains of C. graminicola were able to efficiently adapt to media containing azoles, and those adapted to tebuconazole were less sensitive to all tested agricultural and medical azoles than the nonadapted control strain [28]. In addition, tebuconazole induced tandem repeat expansion in the promoter region of cyp51A in A. fumigatus isolates in vitro, indicating that fungicide pressure can rapidly select adaptive genomic changes in this mold [29]. Agriculturally selected antibiotic resistance has also been reported in many bacteria, contributing to the broad distribution of multidrug-resistant pathogenic bacteria in patients and hospitals. While horizontal gene transfer is an important mechanism for the spread of antibiotic-resistant genes among bacteria, this mechanism is not commonly found in fungal pathogens. However, similar to that in bacterial pathogens, once multidrug-resistant genotypes arise in fungal pathogens, such genotypes can spread very quickly to other geographic regions and ecological niches through vegetative cells and airborne spores such as conidia.

Fig. 1. Diagrammatic representation of similar structural binding mode of medical triazoles and triazole fungicides to cyp51A of wild-type A. fumigatus.

(a) Dihalogenated phenyl group of triazoles forms van der Waals contact with the hydrophobic residues (encircled in red) of the active site (cyp51A), and the nitrogen atom of the five-membered aromatic ring of triazoles binds to the cyp51A heme moiety. In addition, the D-ring propionate (C2H5COO−) of the heme moeity forms hydrogen bonds with the side-chain hydroxyl group of triazoles. (b) Triazole fungicides show similar van der Waals contact at the hydrophobic pocket. However, the nitrogen atom of the five-membered aromatic ring of fungicide triazoles binds to the Ser297 residue at the active site. In addition, the triazoles tebuconazole and epoxiconazole are known to interact with the His296 residue while penconazole and metconazole form water-bridging interactions at the active site. Clonal Expansion and Fitness of TR34/L98H Aspergillus fumigatus Strains

A recent analysis of 255 Dutch A. fumigatus isolates using 20 molecular markers identified five distinct genotype groups in the Netherlands. Interestingly, all the multi-triazole resistant (MTR) isolates with the TR34/L98H mutation belonged to one group and, overall, they were genetically less variable than susceptible isolates [30], consistent with a single and recent origin of the resistant genotype. Similarly, all MTR A. fumigatus clinical and environmental strains obtained from diverse geographical regions from India belonged to a single multilocus microsatellite genotype [21]. The genotype analysis suggested that the ARAF genotype in India was likely an extremely adaptive recombinant progeny derived from a cross between azole-resistant strains migrated from outside of India and a native azole-susceptible strain from within India, followed by mutation. The abundant phylogenetic incompatibility is consistent with sexual mating in natural populations of this species in India [21].

A potential consequence of harboring the multidrug-resistant mutations in ARAF strains might be a reduced fitness in the absence of the drug as compared to the wild-type isolates. However, evidence so far suggested that the TR34/L98H mutation had little or no adverse fitness consequence. For example, the composite survival index (CSI) was used to measure the virulence properties of the cyp51A gene–associated resistance mechanism in A. fumigatus isolates [31]. The analyses revealed that strains with the TR34/L98H mutation had virulence comparable to the wild-type controls and there was no growth impairment and no reduction of virulence with the TR34/L98H mutation [31]. A similar finding was reported about the fitness of azole-resistant C. albicans strains with mutations in the ERG3 gene, with the mutants retaining filamentation and virulence properties [32]. The rapid dispersal of the ARAF strains with the TR34/L98H genotype among regions within Asia also supports the hypothesis that these strains have robust fitness in natural environments, with comparable or even higher fitness than that of wild-type strains [21], [23]. However, we would like to note that the development of azole resistance in clinical ARAF isolates carrying mutations at other loci (i.e., the non-cyp51A gene) could result in a reduction of virulence [33].

Perspectives

The rapid spread of ARAF strains is jeopardizing the treatment of patients with Aspergillus diseases, ruling out the use of oral antifungals for these patients and leaving only the option of intravenous amphotericin B or echinocandins. Amphotericin B has significant detrimental side-effects and echinocandins are unable to completely kill or inhibit Aspergillus and, as such, they have only been licensed for salvage therapy of invasive aspergillosis. At present, antifungal susceptibility testing of A. fumigatus against azoles is not commonly performed and thus the overall threat of ARAF is not yet completely known. However, it would be beneficial to (i) have an active multi-azole susceptibility testing of A. fumigatus to monitor the extent of the problem, (ii) reduce agricultural use of triazole DMI fungicides, and (iii) use combination drug therapy when dealing with infections by A. fumigatus strains to limit the emergence of resistance. Indeed, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/Forms/ECDC_DispForm.aspx?ID=1064) recommends increased surveillance for clinical and environmental azole-resistant pathogens and to conduct field trials to study the impact of nonmedical azole use in the development of azole resistance in patients. A more judicious use of azoles in patients, in agriculture settings, and alternative strategies such as chemosensitization and/or a shift from the use of purely chemical methods to a more integrated crop management approach could help lower the dosage levels of fungicides in the environment and minimize the emergence and spread of ARAF.

Although there are substantial data suggesting that agricultural use of fungicides have driven the emergence and spread of multi-triazole-resistant strains of A. fumigatus, conclusive evidence linking agricultural triazole fungicides to the emergence of TR34/L98H or TR46/Y121F/T289A genotypes in controlled field experiments is lacking. The definite evidence will help the regulatory authorities with formulation of policies to control the environmental-driven azole resistance. The two major types of azole-resistant mutations were first detected in 1998 and 2009 respectively and both are now spreading quickly (Figure 2). It is highly likely that other types of mutations conferring multiple azole resistance could emerge in the near future from environmental sources and spread among human populations.

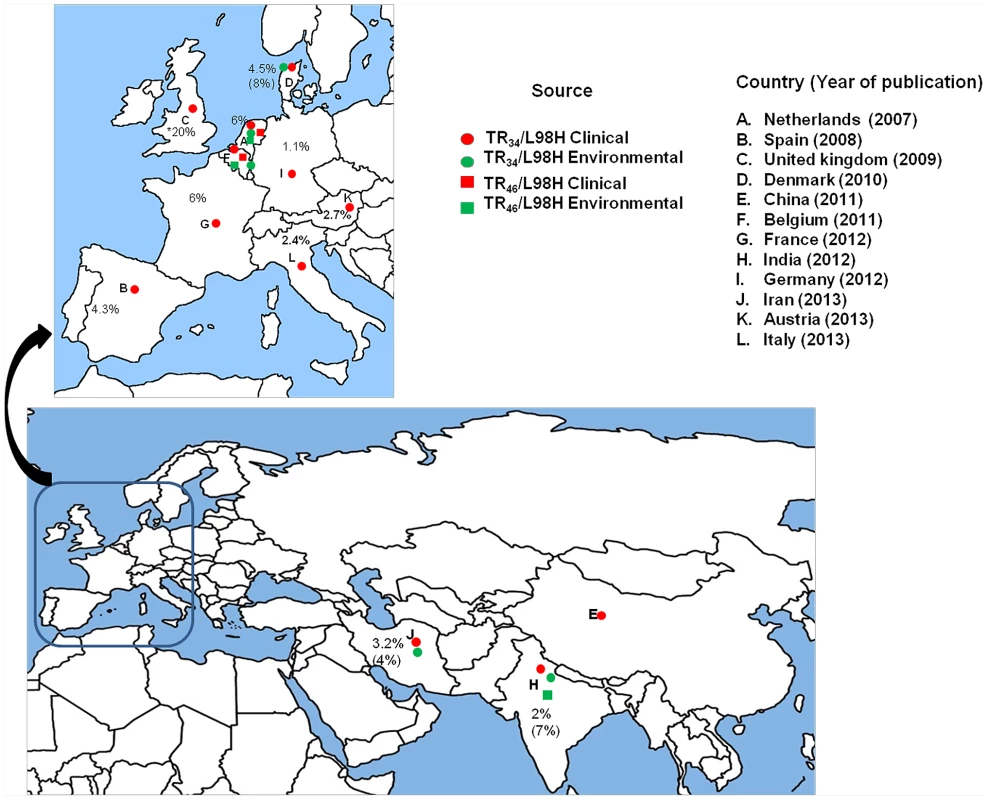

Fig. 2. A global map depicting geographic distribution of multi-triazole-resistant clinical (red) and environmental (green) Aspergillus fumigatus strains carrying the TR34/L98H (circle) and the TR46/Y121F/T289A mutations (square).

Countrywide prevalence rates (%) of A. fumigatus carrying TR34/L98H are presented excepting the United Kingdom, where overall azole resistance is illustrated. The percent in parentheses denotes environmental prevalence rates.

Zdroje

1. BrownGD, DenningDW, GowNA, LevitzSM, NeteaMG, et al. (2012) Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 4 : 165rv13.

2. DenningD, PleuvryA, ColeD (2013) Global burden of ABPA in adults with asthma and its complication chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in adults. Med Mycol 51 : 361–370.

3. Lass-FlörlC (2011) Triazole antifungal agents in invasive fungal infections: a comparative review. Drugs 71 : 2405–2419.

4. Van der Linden JWM, Arendrup MC, Verweij PE, SCARE network (2011) Prospective international surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: SCARE-Network. In: 51st Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC); Sep 17–20; Chicago, IL. Abstract M-490. (SCARE-NETWORK).

5. PfallerMA, BoykenL, HollisR, KroegerJ, MesserS, et al. (2011) Use of epidemiological cutoff values to examine 9-year trends in susceptibility of Aspergillus species to the triazoles. J Clin Microbiol 49 : 586–590.

6. Krishnan-Natesan S, Swaminathan S, Cutright J, et al.. (2010) Antifungal susceptibility pattern of Aspergillus fumigatus isolated from clinical specimens in Detroit Medical Center (DMC): rising frequency of high MIC of azoles (2003–2006). In: The 50th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC); Sep 12–15; Boston, MA, USA.

7. ChowdharyA, KathuriaS, RandhawaHS, GaurSN, KlaassenCH, et al. (2012) Isolation of multiple-triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains carrying the TR/L98H mutations in the cyp51A gene in India. J Antimicrob Chemother 67 : 362–366.

8. SeyedmousaviS, HashemiSJ, ZibafarE, ZollJ, HedayatiMT, et al. (2013) Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus, Iran. Emerg Infect Dis 19 : 832–834.

9. LockhartSR, FradeJP, EtienneKA, PfallerMA, DiekemaDJ, et al. (2011) Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from the ARTEMIS global surveillance study is primarily due to the TR/L98H mutation in the cyp51A gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55 : 4465–4468.

10. BowyerP, MooreCB, RautemaaR, DenningDW, RichardsonMD (2011) Azole antifungal resistance today: focus on Aspergillus. Curr Infect Dis Rep 13 : 485–491.

11. SneldersE, van der LeeHAL, KuijpersJ, RijsAJMM, VargaJ, et al. (2008) Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS Med 5: e219 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050219

12. Van der LindenJWM, SneldersE, KampingaGA, RijndersBJA, MattssonE, et al. (2011) Clinical implications of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus, the Netherlands, 2007–2009. Emerg Infect Dis 17 : 1846–1852.

13. HowardSJ, CerarD, AndersonMJ, AlbarragA, FisherMC, et al. (2009) Frequency and evolution of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus associated with treatment failure. Emerg Infect Dis 15 : 1068–1076.

14. ArendrupMC, MavridouE, MortensenKL, SneldersE, Frimodt-MøllerN, et al. (2010) Development of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus during azole therapy associated with change in virulence. PLoS ONE 5: e10080 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010080

15. SneldersE, KarawajczykA, VerhoevenRJA, VenselaarH, SchaftenaarG, et al. (2011) The structure–function relationship of the Aspergillus fumigatus cyp51A L98H conversion by site-directed mutagenesis: the mechanism of L98H azole resistance. Fungal Genet Biol 48 : 1062–1070.

16. FraczekMG, BromleyM, BuiedA, MooreCB, RajendranR, et al. (2013) The cdr1B efflux transporter is associated with non-cyp51A mediated itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. J Antimicrob Chemother 68 : 1486–1496.

17. MelladoE, Garcia-EffronG, Alcazar-FuoliL, MelchersWJ, VerweijPE, et al. (2007) A new Aspergillus fumigatus resistance mechanism conferring in vitro cross-resistance to azole antifungals involves a combination of cyp51A alterations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51 : 1897–904.

18. SneldersE, Karawajczyk, SchaftenaarG, VerweijPE, MelchersWJ (2010) Azole resistance profile of amino acid changes in Aspergillus fumigatus cyp51A based on protein homology modeling. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54 : 2425–2430.

19. SneldersE, Huis In 't VeldRA, RijsAJJM, KemaGHJ, MelchersWJ, et al. (2009) Possible environmental origin of resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus to medical triazoles. Appl Environ Microbiol 75 : 4053–4057.

20. DenningDW, ParkS, Lass-FlörlC, FraczekMG, KirwanM, et al. (2011) High-frequency triazole resistance found in nonculturable Aspergillus fumigatus from lungs of patients with chronic fungal disease. Clin Infect Dis 52 : 1123–1129.

21. ChowdharyA, KathuriaS, XuJ, SharmaC, SundarG, et al. (2012) Clonal expansion and emergence of environmental multiple-triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains carrying the TR34/L98H mutations in the cyp51A gene in India. PLoS ONE 7: e52871 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052871

22. MortensenKL, MelladoE, Lass-FlörlC, Rodriguez-TudelaJL, JohansenHK, et al. (2010) Environmental study of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus and other aspergilli in Austria, Denmark, and Spain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54 : 4545–4549.

23. BadaliH, VaeziA, HaghaniI, YazdanparastSA, HedayatiMT, et al. (2013) Environmental study of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus with TR34/L98H mutations in the cyp51A gene in Iran. Mycoses doi:10.1111/myc.12089. In press

24. van der LindenJW, CampsSM, KampingaGA, ArendsJP, Debets-OssenkoppYJ, et al. (2013) Aspergillosis due to voriconazole highly resistant Aspergillus fumigatus and recovery of genetically related resistant isolates from domestic homes. Clin Infect Dis 57 : 513–520.

25. VermeulenE, MaertensJ, SchoemansH, LagrouK (2012) Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus due to TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation emerging in Belgium, July 2012. Euro Surveill 17. pii: 20326.

26. ChowdharyA, SharmaC, KathuriaS, HagenF, MeisJF (2013) Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus with the environmental TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation in India. J Antimicrob Chemother doi:10.1093/jac/dkt397. In press

27. VerweijPE, KemaGH, ZwaanB, MelchersWJ (2013) Triazole fungicides and the selection of resistance to medical triazoles in the opportunistic mould Aspergillus fumigatus. Pest Manag Sci 69 : 165–170.

28. SerflingA, WohlrabJ, DeisingHB (2007) Treatment of a clinically relevant plant-pathogenic fungus with an agricultural azole causes cross-resistance to medical azoles and potentiates caspofungin efficacy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51 : 3672–3676.

29. SneldersE, CampsSMT, KarawajczykA, SchaftenaarG, KemaGHJ, et al. (2012) Triazole fungicides can induce cross-resistance to medical triazoles in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS ONE 7: e31801 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031801

30. KlaassenCH, GibbonsJG, FedorovaND, MeisJF, RokasA (2012) Evidence for genetic differentiation and variable recombination rates among Dutch populations of the opportunistic human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol Ecol 21 : 57–70.

31. MavridouE, MeletiadisJ, JancuraP, AbbasS, ArendrupMC, et al. (2013) Composite survival index to compare virulence changes in azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates. PLoS ONE 8: e72280 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072280

32. Vale-Silva, CosteAT, IscherF, ParkerJE, KellySL, et al. (2012) Azole resistance by loss of function of the sterol Δ5,6 - desaturase gene (ERG3) in Candida albicans does not necessarily decrease virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56 : 1960–1968.

33. CampsSMT, DutilhBE, ArendrupMC, RijsAJMM, SneldersE, et al. (2012) Discovery of a hapE mutation that causes azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus through whole genome sequencing and sexual crossing. PLoS ONE 7: e50034 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050034

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 10- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Infekční komplikace virových respiračních infekcí – sekundární bakteriální a aspergilové pneumonie

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Are We There Yet? Recent Progress in the Molecular Diagnosis and Novel Antifungal Targeting of and Invasive Aspergillosis

- Fungal Iron Availability during Deep Seated Candidiasis Is Defined by a Complex Interplay Involving Systemic and Local Events

- Emergence of Azole-Resistant Strains due to Agricultural Azole Use Creates an Increasing Threat to Human Health

- Fungal Adenylyl Cyclase Acts As a Signal Sensor and Integrator and Plays a Central Role in Interaction with Bacteria

- Sensing of the Microbial Neighborhood by

- Antivirulence Therapy for Animal Production: Filling an Arsenal with Novel Weapons for Sustainable Disease Control

- The Cell Biology of : How to Teach Using Animations

- A Structure-Guided Mutation in the Major Capsid Protein Retargets BK Polyomavirus

- RNA Biology in Fungal Phytopathogens

- , , and the Human Mouth: A Sticky Situation

- The Gene Is Essential for Resistance to Human Serum in

- Unisexual Reproduction Drives Evolution of Eukaryotic Microbial Pathogens

- Bacterial Pathogens Activate a Common Inflammatory Pathway through IFNλ Regulation of PDCD4

- Bats and Viruses: Friend or Foe?

- Protein Trafficking through the Endosomal System Prepares Intracellular Parasites for a Home Invasion

- IL-22 Mediates Goblet Cell Hyperplasia and Worm Expulsion in Intestinal Helminth Infection

- B Cells Enhance Antigen-Specific CD4 T Cell Priming and Prevent Bacteria Dissemination following Genital Tract Infection

- Alternative Roles for CRISPR/Cas Systems in Bacterial Pathogenesis

- Chemicals, Climate, and Control: Increasing the Effectiveness of Malaria Vector Control Tools by Considering Relevant Temperatures

- Dengue Vaccines: Strongly Sought but Not a Reality Just Yet

- Feeding Uninvited Guests: mTOR and AMPK Set the Table for Intracellular Pathogens

- Driven Enforced Viral Replication in Dendritic Cells Contributes to Break of Immunological Tolerance in Autoimmune Diabetes

- IL-4Rα-Associated Antigen Processing by B Cells Promotes Immunity in Infection

- A Gammaherpesvirus Uses Alternative Splicing to Regulate Its Tropism and Its Sensitivity to Neutralization

- MicroRNA-155 Promotes Autophagy to Eliminate Intracellular Mycobacteria by Targeting Rheb

- Epigenetic Dominance of Prion Conformers

- MAIT Cells Detect and Efficiently Lyse Bacterially-Infected Epithelial Cells

- The Role of TcdB and TccC Subunits in Secretion of the Tcd Toxin Complex

- A Mechanism for the Inhibition of DNA-PK-Mediated DNA Sensing by a Virus

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Dengue Vaccines: Strongly Sought but Not a Reality Just Yet

- MicroRNA-155 Promotes Autophagy to Eliminate Intracellular Mycobacteria by Targeting Rheb

- Alternative Roles for CRISPR/Cas Systems in Bacterial Pathogenesis

- Feeding Uninvited Guests: mTOR and AMPK Set the Table for Intracellular Pathogens

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání