-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Multiple Signals Converge on a Differentiation MAPK Pathway

An important emerging question in the area of signal transduction is how information from different pathways becomes integrated into a highly coordinated response. In budding yeast, multiple pathways regulate filamentous growth, a complex differentiation response that occurs under specific environmental conditions. To identify new aspects of filamentous growth regulation, we used a novel screening approach (called secretion profiling) that measures release of the extracellular domain of Msb2p, the signaling mucin which functions at the head of the filamentous growth (FG) MAPK pathway. Secretion profiling of complementary genomic collections showed that many of the pathways that regulate filamentous growth (RAS, RIM101, OPI1, and RTG) were also required for FG pathway activation. This regulation sensitized the FG pathway to multiple stimuli and synchronized it to the global signaling network. Several of the regulators were required for MSB2 expression, which identifies the MSB2 promoter as a target “hub” where multiple signals converge. Accessibility to the MSB2 promoter was further regulated by the histone deacetylase (HDAC) Rpd3p(L), which positively regulated FG pathway activity and filamentous growth. Our findings provide the first glimpse of a global regulatory hierarchy among the pathways that control filamentous growth. Systems-level integration of signaling circuitry is likely to coordinate other regulatory networks that control complex behaviors.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000883

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000883Summary

An important emerging question in the area of signal transduction is how information from different pathways becomes integrated into a highly coordinated response. In budding yeast, multiple pathways regulate filamentous growth, a complex differentiation response that occurs under specific environmental conditions. To identify new aspects of filamentous growth regulation, we used a novel screening approach (called secretion profiling) that measures release of the extracellular domain of Msb2p, the signaling mucin which functions at the head of the filamentous growth (FG) MAPK pathway. Secretion profiling of complementary genomic collections showed that many of the pathways that regulate filamentous growth (RAS, RIM101, OPI1, and RTG) were also required for FG pathway activation. This regulation sensitized the FG pathway to multiple stimuli and synchronized it to the global signaling network. Several of the regulators were required for MSB2 expression, which identifies the MSB2 promoter as a target “hub” where multiple signals converge. Accessibility to the MSB2 promoter was further regulated by the histone deacetylase (HDAC) Rpd3p(L), which positively regulated FG pathway activity and filamentous growth. Our findings provide the first glimpse of a global regulatory hierarchy among the pathways that control filamentous growth. Systems-level integration of signaling circuitry is likely to coordinate other regulatory networks that control complex behaviors.

Introduction

Signal transduction pathways regulate the response to extracellular stimuli. Complex behaviors frequently require the action of multiple pathways that act in concert to reprogram cell fate. In metazoan development for example, a highly regulated network of interactions between evolutionarily conserved pathways like Notch and EGFR coordinates every facet of cell growth and differentiation [1]. An important question therefore is to understand how different pathway activities are coordinated during complex behaviors. Addressing this question is increasingly problematic because signaling pathways operate in vast interconnected web-like information networks [2]. Miscommunication between pathways is an underlying cause of diseases such as cancer [3], and therefore it is both critically important and extremely challenging to precisely define the regulatory connections among signaling pathways.

The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae undergoes a variety of different responses to extracellular stimuli as a result of the function of evolutionarily conserved signal transduction pathways. In response to nutrient limitation, yeast undergoes filamentous growth [4],[5],[6], a cellular differentiation response in which changes in polarity, cell-cycle progression, and gene expression induce the formation of branched chains of interconnected and elongated filaments. The filamentous cell type is widely regarded as a model for differentiation [7],[8],[9],[10], and in pathogens like Candida albicans, filamentous growth is a critical aspect of virulence [11],[12],[13].

A number of different pathways are required for filamentous growth (Figure 1A, left panel). These include a MAPK pathway commonly referred to as the FG pathway (Figure 1A, right panel [14],[15],[16]), the RAS pathway [4],[17], the target of rapamycin or TOR pathway [18], the RIM101 pathway [19],[20],[21], the retrograde pathway (RTG [7]), the inositol regulatory transcription factor Opi1p [22], and a global glucose control protein kinase Snf1p [23],[24],[25]. It is not clear whether these different pathways function together or independently to regulate filamentous growth. This question is compounded by the fact that several hundred other proteins have been implicated in the filamentation response [7],[26],[27].

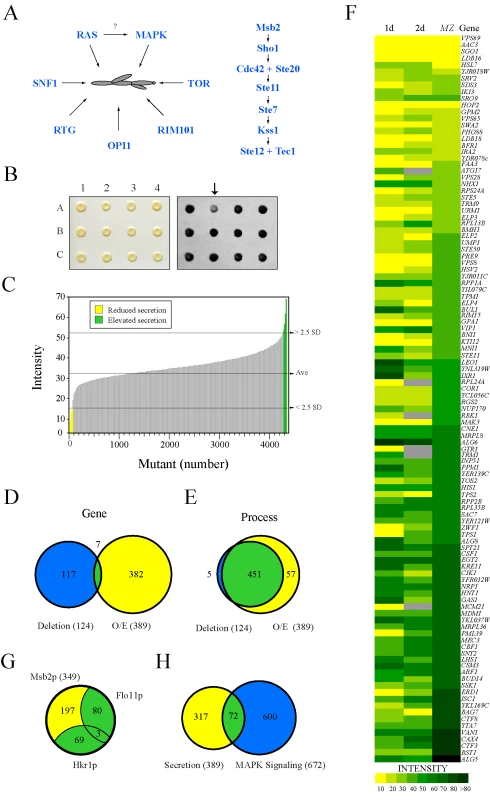

Fig. 1. Secretion profiling of Msb2p.

(A) Filamentous growth regulation in yeast. At left, different regulatory proteins and pathways that have been implicated in filamentous growth. It is unclear whether RAS regulates the FG pathway, as shown by the question mark. At right, the FG MAPK pathway. Cell surface proteins Msb2p and Sho1p connect to the Rho GTPase Cdc42p and effector p21 activated kinase Ste20p. The MAPKKK Ste11p, MAPKK Ste7p, and MAPK Kss1p regulate the activity of the transcription factors Ste12p and Tec1p. (B) Colonies from the MATa deletion collection containing pMSB2-HA were pinned to nitrocellulose filters on SD-URA medium and incubated for 48h (left panel). Filters were rinsed in a stream of water and probed with anti-HA antibodies to detect shed Msb2p-HA (right panel). The mutant at position A2 (arrow) was identified as defective for Msb2p-HA secretion. (C) The secretion profile of Msb2p-HA in the haploid (MATa) ordered deletion collection. Y-axis, normalized spot intensity (Intensity) as a measure of secreted Msb2p-HA. X-axis, deletion mutants ranked by normalized spot intensity. Yellow, mutants that showed a decrease (2.5 standard deviations below average, - 2.5 SD) in Msb2p-HA secretion. Green, mutants that showed elevated Msb2p-HA secretion (2.5 SD above average). (D) Overlap between genes identified in the deletion screen (blue circle at left, 124 genes) and the overexpression (O/E) screen (yellow circle at right, 389 genes). Seven common genes were identified (see Table S4C for details). (E) Overlap based on genes that share a common process/function. (F) Heat map showing normalized spot intensity (at 1d and 2d intervals) as a readout of Msb2p secretion compared to expression levels of an MSB2-lacZ (MZ) reporter. Yellow, reduced secretion; green, elevated secretion; grey, N/D. See Table S5 for details. (G) Comparative mucin secretion profiling. Genes that influence Msb2p-HA secretion when overexpressed (∼389 genes) were examined in strains containing Hkr1p-HA (PC2740) and Flo11p-HA (PC2043). Yellow, Msb2p-specific genes; blue, genes common to multiple mucins (Table S8). (H) Comparison between the secretion profile of Msb2p and regulators of a MAPK pathway growth reporter (FUS1-HIS3, [134]) whose expression is dependent upon the transcription factor Ste12p and elements of the STE pathway [135],[136],[137]. To identify new aspects of filamentous growth regulation, we developed a screening approach to identify regulators of the MAPK pathway that controls filamentous growth. The FG pathway is regulated by the signaling mucin Msb2p [28], a cell-surface glycoprotein [29] that mediates signaling through the RHO guanine nucleotide triphosphatase (GTPase) Cdc42p [30]. Msb2p is processed in its extracellular domain by the aspartyl protease Yps1p, and release of the extracellular domain is required for FG pathway activation [31]. By measuring release of the extracellular domain of Msb2p in complementary genomic collections, we identified new regulators of the FG pathway. Unexpectedly, many of the major filamentation regulatory pathways (RAS, RIM101, OPI1, and RTG) were found to be required for MAPK activation. Our study indicates that the pathways that control filamentous growth are connected in co-regulatory circuits, which brings to light a systems-level coordination of this differentiation response.

Results

Secretion Profiling as an Approach to Identify FG Pathway Regulatory Proteins

To identify new regulators of the FG pathway, secretion of the extracellular domain of Msb2p [31] was examined using a high-throughput screening (HTS) approach in complementary genomic collections. Similar approaches have identified regulators of protein trafficking by mis-sorting and secretion of carboxypeptidase Y [32],[33],[34]. An ordered collection of 4,845 mutants deleted for nonessential open reading frames (ORFs, [35]) was transformed with a plasmid carrying a functional epitope-tagged MSB2-HA fusion gene, and transformants were screened by colony immunoblot to identify mutants with altered Msb2p-HA secretion (Figure 1B). Computational methods were used to quantitate, normalize, and compare secretion between mutants, which allowed ranking by the level of secreted Msb2p-HA (Table S3). As a result, 67 mutants were identified that showed reduced secretion of Msb2p-HA (Figure 1C, yellow), and 58 mutants were identified that showed elevated secretion (Figure 1C, green).

The secretion of Msb2p was also examined using an overexpression collection of 5,411 ORFs under the control of the inducible GAL1 promoter [36]. This collection allows examination of essential genes and can be assessed in the Σ1278b background, in which filamentous growth occurs in an Msb2p - and MAPK pathway-dependent manner [37]. Approximately 390 genes were identified that influenced the secretion of Msb2p-HA when overexpressed (Table S4). The two screens identified few common genes (Figure 1D, 1.5% overlap), which is not entirely surprising given that gene overexpression does not necessarily induce the same (or opposite) phenotype as gene deletion [38] and because the two backgrounds exhibit different degrees of filamentous growth [37]. Significant overlap was observed at the level of gene process/function (Figure 1E, 89% overlap), which resulted in classification of genes into different functional categories (Figure S1; Tables S3 and S4). Introduction of an MSB2-lacZ reporter showed a high correlation between genes that affect Msb2p secretion and MSB2 expression (Figure 1F; compare 1d to MZ). Because MSB2 is itself a target of the FG pathway [28], many of the genes identified likely influence the activity of the FG pathway.

In total, 505 genes were identified that influenced Msb2p secretion, which might represent an underestimate due to the stringent statistical cutoff employed. This unexpectedly large collection suggests that Msb2p is subject to extensive regulation, although presumably many of these genes exert their effects indirectly. To enrich for genes that specifically regulate the FG pathway, secondary tests were performed. In one test, the secretion profile of Msb2p was compared to the secretion profile of two other mucins, the signaling mucin Hkr1p [39],[40] and transmembrane mucin Flo11p [41],[42]. Almost half the genes were common to multiple mucins (44%, Figure 1G) and may function in the general maturation of large secreted glycoproteins. In a second test, the secretion profile of Msb2p was compared to a genomic screen for genes that when overexpressed influence the expression of a FG pathway-dependent reporter (Figure 1H). These tests eliminated general regulators of mucin maturation/trafficking and enriched for potential MAPK regulatory proteins (∼72 candidate genes).

Several mutants were identified that were expected to influence Msb2p secretion. Mutants lacking FG pathway components (see Figure 1A), which are required for MSB2 expression in a positive feedback loop [28], showed a defect in Msb2p-HA secretion (ste20Δ, ste50Δ, ste11Δ, and ste7Δ; Table S3). The mutant lacking the aspartyl protease Yps1p, which processes Msb2p and is required for release of the extracellular domain [31], was also identified (yps1Δ; Table S3). A subset of the genes that influence Msb2p secretion but not its expression might function through regulating expression of the YPS1 gene, which is highly regulated [43]. The cell-cycle regulatory transcription factors Swi4p and Swi6p [44],[45],[46],[47],[48], were also found to regulate Msb2p secretion (Table S3B and S7). The swi4 and swi6 mutants had different phenotypes in Msb2p-HA secretion (Table S3), which suggests that the Swi4p and Swi6p proteins may play different roles in regulating cell-cycle dependent expression of the MSB2 gene [49]. Some mating pathway-specific genes (STE5) were also identified, which may have an as yet unappreciated role in communication between the mating and FG pathways, which share a number of components [50].

As a proof-of-principle test, we disrupted fourteen genes that came out of the deletion screen in the Σ1278b background and tested for defects in Msb2p-HA secretion and FG pathway signaling. The test showed a >70% recovery rate based on phenotype and identified a novel connection between the tRNA modification complex Elongator and MSB2 expression, establishing this protein complex as a novel regulator of the MAPK pathway [51]. Therefore, secretion profiling is a valid approach to identify established and potentially novel regulators of the FG pathway.

Multiple Signaling Pathways Regulate the FG Pathway

To identify new genes that regulate the FG pathway, ∼50 candidate genes were disrupted in wild-type strains of the Σ1278b background, and the resulting mutants were tested for effects on FG pathway activity. To distinguish between mutants that influence filamentous growth from those that have a specific effect on FG pathway activity, a transcriptional reporter (FUS1) was used that in Σ1278b strains lacking an intact mating pathway (ste4) is dependent upon Msb2p and other FG pathway components including the transcription factor Ste12p (Figure 2A and 2B [28]). A number of potential MAPK regulatory proteins were identified by this approach, many of which have been implicated in regulating filamentous growth through their functions in other pathways.

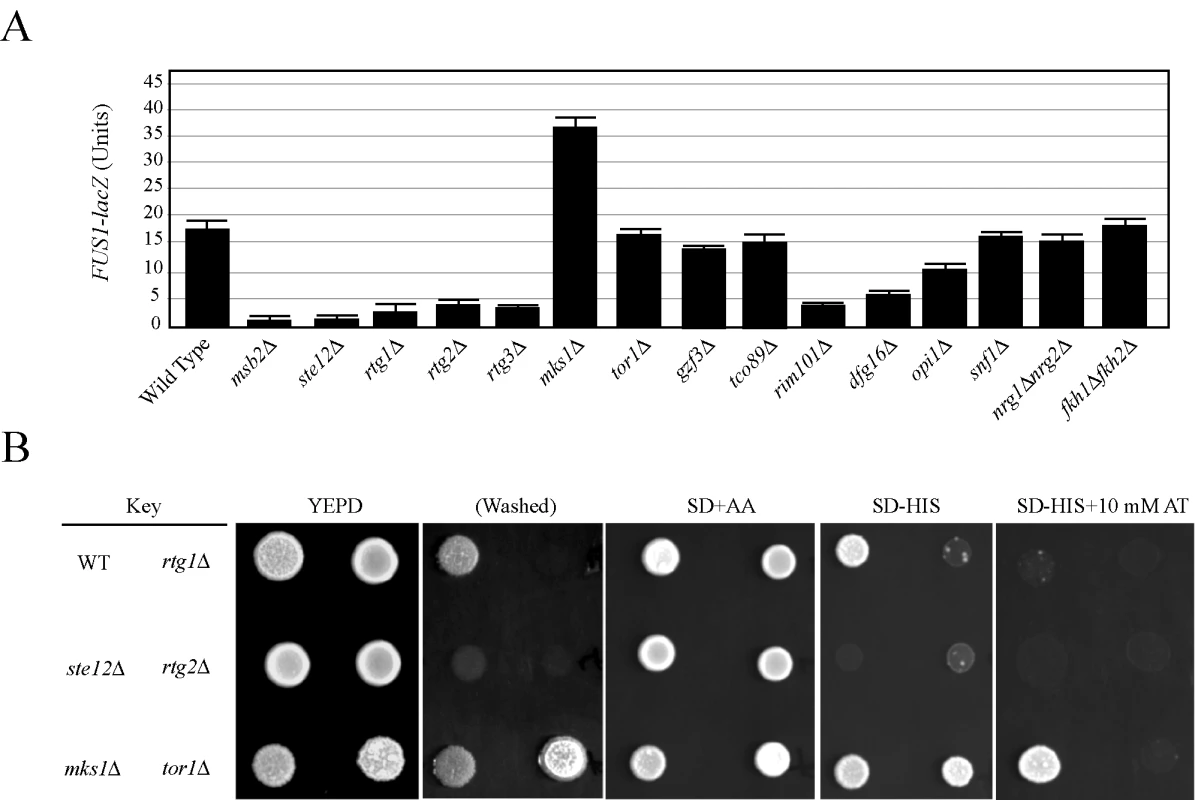

Fig. 2. The role of filamentation control proteins on FG pathway activity.

(A) FUS1-lacZ expression was monitored in the indicated strains in mid-log phase grown in YEPD medium. The experiment was performed in duplicate, and error bars represent standard deviation between experiments. In synthetic medium, the opi1 mutant showed a >3-fold decrease in FUS1-lacZ expression compared to wild type (data not shown). (B) Comparison between FUS1-HIS3 expression and invasive growth for a subset of mutants shown in (A). Equal concentrations of cells were spotted onto YEPD medium or synthetic medium containing glucose (SD) and all amino acids (AA), amino acids except histidine (-HIS), or amino acids except histidine and containing the competitive inhibitor 4-amino-1,2,4-triazole. After two days, the plates were photographed. The YEPD plate was photographed, washed in a stream of water, and photographed again (Washed). Growth on SD-HIS is indicative of MAPK pathway activity. Growth on SD-HIS+AT is indicative of hyperactivity. Although the tor1 mutant induces hyperinvasive growth it does not influence MAPK activity. Mitochondrial retrograde signaling (the RTG network), which is responsible for mitochondrial communication with the nucleus, was required for FG pathway signaling. The RTG network responds to the integrity of the mitochondria and nutrient state, specifically the availability of certain amino acids. The proteins Rtg1p, Rtg2p, and Rtg3p are the main targets of the pathway, and these factors initially induce the expression of genes involved in the TCA cycle [52]. Rtg1p, Rtg2p, and Rtg3p were required for FG pathway signaling (Figure 2A). These factors are under the control of Mks1p, which inhibits Rtg3p translocation to the nucleus, preventing expression of target genes [53]. Mks1p is subsequently under the control of Rtg2p, which will bind and sequester Mks1p and prevent its interaction with Rtg3p [54]. Consistent with its inhibitory role in the RTG pathway, Mks1p had an inhibitory role on FG pathway activity (Figure 2A and 2B). Rtg2p, in turn, is negatively regulated by the Tor1p complex via Lst8p [55]. Several mitochondrial components, including ribosomal subunits and enzymes of the TCA cycle, showed varied expression and signaling defects in the screen (Tables S3 and S4; Figure S7A). Deletion of Tor1p did not have the same effect as Mks1p (Figure 2A and 2B), but it has been shown that RTG can function independently of Tor1p inputs [56]. Consistent with a connection to RTG, the activity of the FG pathway was sensitive to certain amino acids such as glutamate (Figure S2).

Components of the Rim101p pathway [19], including the transcriptional repressor Rim101p and Dfg16p, which is required for processing and activation of Rim101p [20],[21], were required for FG pathway activity (Figure 2A). The Rim101p pathway is required for pH-dependent invasive growth, and the activity of the FG pathway was slightly sensitive to pH levels (Figure S2). Other regulators of the FG pathway included components of the RAS pathway (see below) and the inositol regulatory transcription factor Opi1p (Figure 2A [57],[58]), which has recently been tied to filamentous growth regulation [22].

The discovery that many filamentous growth regulatory pathways impinge on the FG pathway suggests a systems-level coordination between the pathways that regulate filamentous growth. We directly tested other filamentation regulatory proteins. Filamentous growth is regulated by the global glucose-regulatory protein Snfl1p [23],[24],[25]. Snf1p was not required for FG pathway activity (Figure 2A). The negative regulators Fkh1p/Fkh2p [59] and Nrg1p/Nrg2p [23],[60], which function to inhibit invasive growth, did not influence FG pathway activity (Figure 2A). Therefore, many but not all inputs into filamentous growth regulation also regulate the FG pathway. This finding may begin to account for the large number of genes identified by secretion profiling that impinge on the FG pathway.

Ras2p/cAMP Regulates Starvation-Dependent Induction of MSB2 Expression

The RAS pathway has previously been implicated in FG pathway regulation [61]. However, systematic genomic analyses have failed to substantiate a connection between the two pathways [8],[9],[10],[62],[63],[64],[65], and a prevailing consensus is that the pathways function independently and converge on common targets [66],[67]. We found that the GTPase Ras2p [67],[68] was required for the expression of FG pathway-dependent reporters (Figure 3A), which indicates that the RAS pathway does regulate the FG pathway.

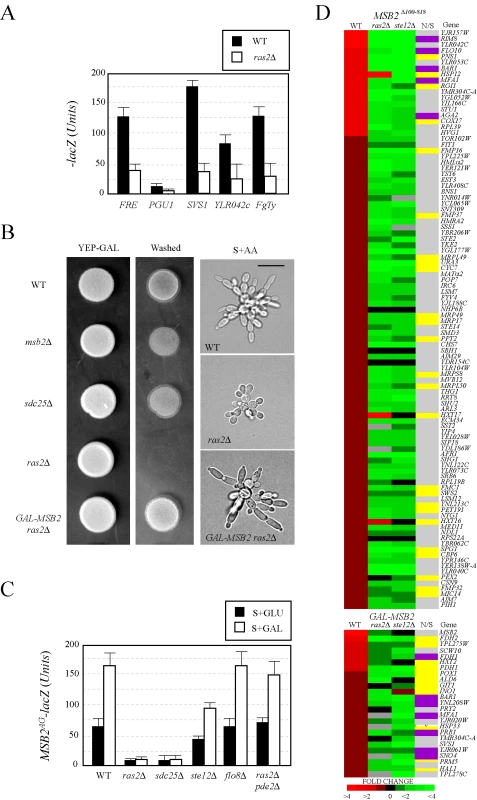

Fig. 3. Components of the RAS pathway are required for MSB2 expression and FG pathway regulation.

(A) Expression of FG pathway-dependent reporters in wild-type cells and the ras2Δ mutant. Cells containing plasmid born lacZ fusions [65] were grown to mid-log phase in SD-LEU medium to maintain selection for the plasmids and harvested by centrifugation. β-galactosidase assays were performed in duplicate. Y-axis, β-galactosidase activity expressed in Miller Units (U). Error bars represent the standard deviation between experiments. (B) Invasive growth assays. For the plate-washing assay at left, equal concentrations of cells were spotted onto YEP-GAL medium and incubated for 2d. The plate was photographed (YEP-GAL) and washed in a stream of water to reveal invaded cells (Washed). For the single-cell invasive growth assay at right, cells were grown on S+GAL medium at low density for 16 hours and photographed at 100X. Bar, 10 microns. (C) MSB2AG-lacZ expression in wild type, ras2Δ, sdc25Δ, flo8Δ, ste12Δ, and ras2Δ pde2Δ mutants grown in SD or S+GAL medium. Y-axis, β-galactosidase activity expressed in Miller Units (U). The experiment was performed in duplicate, and error bars represent standard deviation between experiments. (D) Expression profiling of cells containing an activated FG pathway (either containing an activated allele MSB2Δ100–818 or expressing GAL-MSB2) in wild-type cells the ras2Δ and ste12Δ mutants. Heat map of DNA microarray comparisons is shown. Red, fold induction; green, fold repression; black, no change; grey, N/D. Each spot represents the average of 3 independent comparisons. Genes involved in nutritional (N) scavenging or stress response (S) are marked in yellow (column N/S). Targets of the RIM101 pathway are shown in purple [19]. The complete microarray dataset, including the raw data, statistical analysis, and functional classification of genes is presented in Table S6. To determine where in the FG pathway that Ras2p functions, genetic suppression analysis was performed using alleles of MSB2 and SHO1 that hyperactivate the FG pathway [31]. Previous genetic suppression analysis indicates that Msb2p functions above Sho1p in the FG pathway [28] (Figure 1A). A hyperactive allele of SHO1 (SHO1P120L) bypassed the signaling defect of ras2Δ, whereas the activated allele MSB2Δ100–818 did not (Figure S3A and S3B), indicating that Ras2p functions above Sho1p and at or above the level of Msb2p in the FG pathway. This result led us to test whether Ras2p regulates the expression of the MSB2 gene. Overexpression of MSB2 (GAL-MSB2) bypassed the agar-invasion defect (Figure 3B, left panels) and the cell elongation defect of the ras2Δ mutant (Figure 3B, right panels; Figure S3A), which indicates that Ras2p regulates MSB2 expression. We confirmed that Ras2p was required for the expression of an MSB2-lacZ reporter, including the starvation-dependent induction of MSB2 expression (Figure 3C). This effect was independent of the FG pathway, which also regulates MSB2 expression [28], because it was observed from a reporter lacking the Ste12p recognition sequence (Figure 3C, MSB2AG-lacZ) that makes MSB2 expression Ste12p-insensitive (Figure 3C, ste12Δ). Secretion profiling also uncovered the alternative guanine nucleotide exchange factor Sdc25p [69],[70]. We confirmed that Sdc25p was required for starvation-dependent MSB2 expression (Figure 3C).

Ras2p might regulate MSB2 expression by modulating cAMP levels through activation of adenylate cyclase [71]. As shown in Figure 3C, bypass of the MSB2 expression defect of the ras2Δ mutant was observed in cells lacking the phosphodiesterase PDE2 [72]. The ras2Δ pde2Δ double mutant showed wild-type expression of the MSB2 gene (Table S7), and overexpression of the PDE2 gene inhibited FG pathway activity (Table S4). Sensitizing MSB2 expression to cAMP levels represents a direct nutritional tie into MAPK regulation (Figure S2) and may explain why a large collection of genes that function in nutrient sensing were identified by secretion profiling (23.5%; Tables S3, S4, S5).

Ras2p also functions in a pathway that regulates the activity of the transcription factor Flo8p, which converges along with the FG pathway on the common target FLO11 [8],[66],[73],[74],[75]. The Flo8p pathway is co-regulated by Ras2p and the glucose receptor-heterotrimeric G-protein Gpr1p-Gpa2p [76],[77],[78],[79],[80]. Gpr1p, Gpa2p, and Flo8p were not required for MSB2 expression (Figure 3C, shown for flo8) or FG pathway signaling (Figure S2B). Ras2p also regulates a diverse collection of nutrient - and stress-related responses [81], and the ras2Δ mutant exhibits a number of phenotypes including glycogen accumulation, resistance to oxidative stress [82],[83], enhanced chronological lifespan [84],[85],[86], and resistance to oleate [87]. MAPK pathway mutants did not show these phenotypes (Figure S4A, S4B, S4C, S4D), which suggests that the FG pathway does not regulate Ras2p function. We therefore suggest that the two pathways function in a unidirectional regulatory circuit RAS -> MAPK.

Expression profiling using whole-genome DNA microarrays was used to validate the above results. The expression profiles of cells overexpressing MSB2 or containing a hyperactive allele (MSB2Δ100–818) were compared in wild-type cells, the ras2Δ mutant, and the ste12Δ mutant genome wide (Figure 3D). Most of the genes that showed MSB2-dependent induction (Figure 3D, red) were reduced in the ras2Δ and ste12Δ mutants (Figure 3D, green). Expression profiling identified new targets of the FG pathway, including genes that function in nutrient scavenging, respiration, and the response to stress (Figure 3D; yellow, N/S, Nutrient/Stress). Targets of the RIM101 pathway [19] were also identified (Figure 3D, purple). The induction of nutrient scavenging genes may represent a feed-forward loop where starvation induces FG pathway activation, which results in the induction of genes to sustain foraging. We note that the observed gene expression changes in the microarray profiling studies encompass both direct and indirect effects. To summarize, RAS regulates the FG pathway by regulating the starvation-dependent induction of MSB2 expression.

Rpd3p(L) Regulates MSB2 Expression by Binding to the MSB2 Promoter

To further explore the regulation of MSB2 expression, transcriptional regulatory proteins identified by secretion profiling were examined. The Rpd3p(L) HDAC complex was identified as a strong positive regulator of MSB2 expression. Rpd3p(L) comprises a 12 subunit complex [88] that includes the bridging proteins Sin3p [89],[90] and Sds3p [91]. Rpd3p, Sin3p, and Sds3p were required for starvation-dependent MSB2 expression and to produce wild-type levels of the Msb2p protein (Figure 4A). Rpd3p, Sin3p, and Sds3p were required for the induction of FG pathway reporters (Table S7) and invasive growth (Figure S6A).

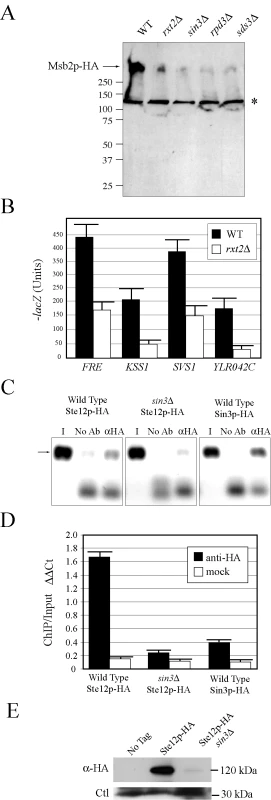

Fig. 4. Rpd3p(L) promotes MSB2 gene expression at the MSB2 promoter.

(A) Immunoblot of Msb2p-HA in wild-type cells and the rxt2Δ, sin3Δ, rpd3Δ, and sds3Δ mutants. The arrow refers to Msb2p-HA. The asterisk refers to a background band. (B) The activity of transcriptional (lacZ) reporters of the FG pathway in wild-type cells and the rxt2Δ mutant. β-galactosidase assays were performed in duplicate, and error bars represent standard deviation between replicates. (C) ChIP analysis of the MSB2 promoter in wild-type cells or the sin3Δ mutant containing Ste12p-HA or Sin3p-HA fusion proteins. I, input; No Ab, no antibody control; αHA, anti-HA antibody. (D) Quantitation of the ChIP data. Graph shows relative levels of binding at the MSB2 promoter relative to an intragenic region and to the ACT1 gene as a control based on quantitative PCR analysis. ΔΔCt, threshold cycle; Bars correspond to the IP/Input ratio. (E) Immunoblot of Ste12p-HA in wild-type cells and the sin3Δ mutant. Ste12p-HA was immunoprecipitated to concentrate the protein. Ctl refers to a background band that served as a loading control. Rpd3p functions in distinct large and small complexes with different cellular functions. Rpd3p(S) recognizes methylated histone H3 subunits and functions to repress spurious transcription initiation from cryptic start sites in open reading frames [92]. Rpd3p(S) contains unique proteins Rco1p and Eaf3p. In contrast, Rpd3p(L) is enriched for different proteins including Rxt2p [92], which is required for Rpd3p(L) function [93]. Immunoblot analysis (Figure 4A), transcriptional reporters (Figure 4B), and invasive growth assays (Figure S6A), showed that Rxt2p was required for MSB2 expression and FG pathway activation. In contrast, Rpd3p(L) was not required for pheromone response pathway activation (Figure S5), which shares components with the FG pathway but induces different target genes [5],[94],[95] and which does not require Msb2p function [28].

Histone deacetylases typically repress gene expression by causing compaction of chromatin into structures inaccessible to transcription factors. With respect to MSB2 expression however, Rpd3p(L) had a positive role. We tested whether Rpd3p(L) negatively regulated an inhibitor of MSB2 expression, such as the transcription factor Dig1p [96],[97],[98] but were unable to find evidence to support this possibility (Figure S6B). Rpd3p(L) functions as a positive regulator of some genes, including targets of the high osmolarity glycerol response (HOG) pathway by direct association with the promoters of HOG pathway targets [99], and in the regulation of some mating-specific targets [100]. Therefore, Rpd3p(L) might positively regulate MSB2 expression by associating with the MSB2 promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis identified Rpd3p(L) at the MSB2 promoter (Figure 4C, Sin3p-HA). In the sin3Δ mutant, less Ste12p was found at the MSB2 promoter (Figure 4C and 4D, compare wild type to sin3Δ). Msb2p and the FG pathway also control STE12 expression. Ste12p-HA protein levels were reduced in the sin3Δ mutant (Figure 4E), as a result of a decrease in STE12 expression determined by q-PCR (data not shown). Therefore, Rpd3p(L) positively regulates the FG pathway by promoting MSB2 expression. Rpd3p(L) may also indirectly promote FG pathway activity by the regulation of other transcription factors that influence MSB2 expression.

Comparative Analysis of MSB2 and FLO11 Gene Regulation

Most of the regulators of MSB2 expression [MAPK, RAS, RIM101, OPI1, and Rpd3p(L)] also regulate expression of FLO11 [22],[66],[101], a target “hub” gene required for cell adhesion during filamentous growth and biofilm formation [8],[18],[42],[66],[102],[103],[104],[105]. Because FLO11 is one of the most highly regulated yeast genes and a target of the FG pathway, we explored the regulation of the two genes in detail.

MSB2 and FLO11 expression were compared by quantitative PCR in a panel of signaling and transcription factor mutants. Phenotypic tests were used to measure FG pathway activity and Flo11p-dependent adhesion (Table S7). As expected, MSB2 and FLO11 expression showed similar dependencies on a number of pathways (Figure 5A, top panel). FLO11 expression was also dependent on genes that did not affect MSB2 expression (Figure 5A, middle panel), including primarily components of the Flo8p pathway. Unexpectedly, FLO11 expression was also dependent on genes that inhibited MSB2 expression, such as snf2Δ and msn1Δ (Figure 5A, bottom panel). Such inhibition might be explained by a negative-feedback loop that functions to dampen the FG pathway.

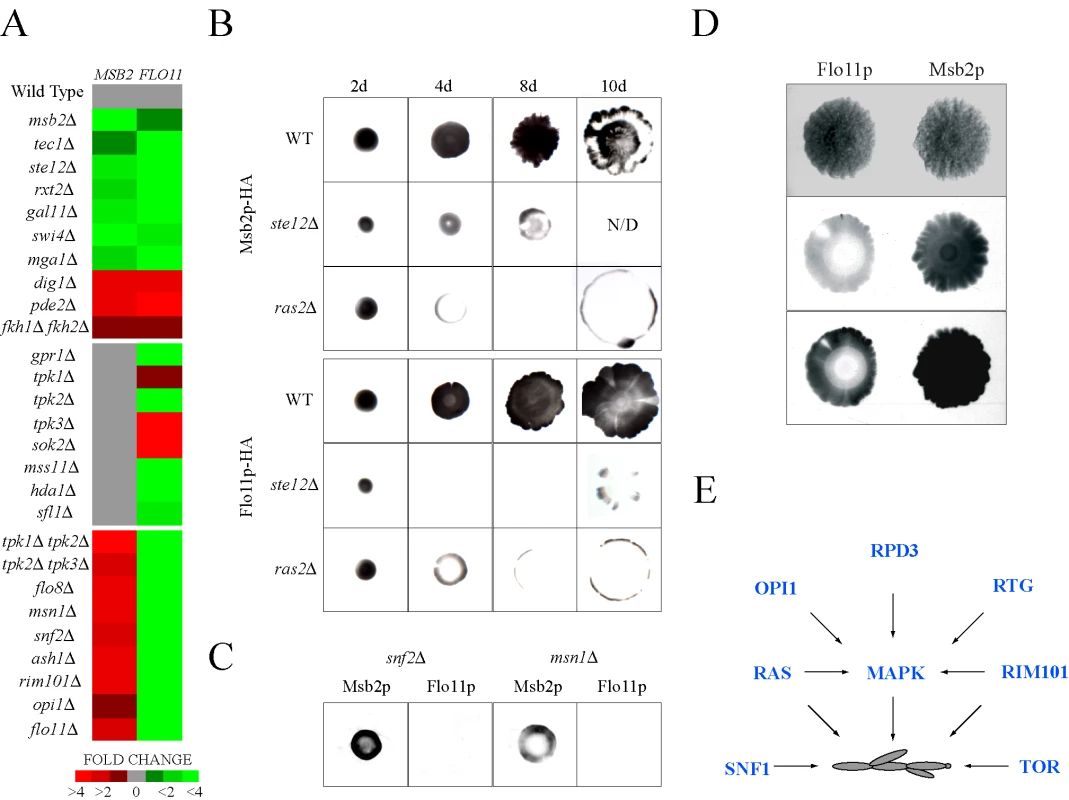

Fig. 5. Comparative expression and secretion profiling of the MSB2 and FLO11 genes.

(A) Quantitative PCR analysis of MSB2 and FLO11 expression in the indicated mutants, all of which were created in the Σ1278b background (Table S1). Heat map shows fold change in gene expression. Red, fold induced; green, fold repressed. See Table S7 for details. (B) Comparison of Msb2p-HA and Flo11p-HA secretion in microbial mats. Mats expressing Msb2p-HA (wild type, PC999; ras2Δ, PC2689; ste12Δ, PC2691) or Flo11p-HA (wild type, PC2043; ras2Δ, PC2693; ste12Δ, PC2695) were spotted onto YEPD medium (0.3% agar) on nitrocellulose filters and were allowed to expand at for 2d, 4d, 8d, and 10d. Cells were washed off the filters, which were probed with antibodies against the HA epitope. Each experiment was performed in duplicate and a representative image is shown. For some panels, the intensity of the secreted protein was below the threshold for visibility in the exposure shown. N/D, not determined. Mat perimeters were at secretion boundaries. (C) Secretion of Msb2p-HA and Flo11p-HA in the snf2Δ and msn1Δ mutants grown as mats for 8d. The experiment was performed as described in (B). (D) Comparison between Msb2p-HA and Flo11p-HA secretion on mats grown on YEP-GAL media for 8d. A light and dark exposure is shown. (E) Model for integration between pathways that control filamentous growth. The RAS, RIM101, and RTG pathways regulate the MAPK pathway. The TOR and SNF1 pathways were not found to influence MAPK activity. The RAS [66] and RIM101 [19] pathways likely regulate filamentous growth at multiple levels. Like Msb2p, Flo11p is a secreted protein [41], which allowed an extensive comparison between the regulation of the two proteins in different conditions and genetic contexts. The levels of secreted proteins were examined in microbial mats, which expand in an Msb2p (MAPK pathway) - and Flo11p-dependent manner [105]. Msb2p-HA and Flo11p-HA showed similar dependencies on Ras2p and the FG pathway transcription factor Ste12p (Figure 5B). A “ring” pattern of Msb2p-HA and Flo11p-HA secretion was observed in the ras2Δ mutant (Figure 5B), which may indicate that Ras2p is required to sustain MSB2 and FLO11 expression in cells exposed to modest nutritional stress, like the interior of expanding mats. In contrast, Flo11p-HA secretion was dependent on proteins on which Msb2p-HA was not (Figure 5C; snf2Δ and msn1Δ). Msb2p-HA and Flo11p-HA showed opposing secretion patterns under some conditions in specific regions of mat interiors (Figure 5D) in agreement with the idea that the two genes are differentially regulated in some contexts. Therefore, expression, phenotypic, and secretion profiling corroborate the existence of a complex, partially overlapping regulatory circuit that governs the regulation of MSB2 and a primary MAPK target hub gene FLO11 (Figure S8).

Discussion

In this study, we address the fundamental question of how different signal transduction pathways function in concert to reprogram cellular behavior. This question is relevant to understanding the complex cellular decision-making underlying many cellular responses. Most studies on signal transduction regulation focus on a single pathway, or on highly related pathways that potentially engage in cross talk [50]. Here we report one of the first attempts to gain a systems-level perspective on the global regulation of a MAPK pathway that controls a differentiation response. This effort relied on primarily genomic approaches including a new technique called secretion profiling, which measures release of a cell-surface MAPK regulatory protein. The “top-view” perspective we obtained has shown that many of the major regulatory proteins that control filamentous growth also control MAPK signaling. This finding is challenging to accept given that many of the pathways are currently viewed as separate entities. Nonetheless, this view is consistent with an emerging systems-level appreciation of pathway regulation in complex situations – cell differentiation, stem cell research, and cancer - where pathway interconnectedness drives the rationale for drug development and new therapeutic endeavors.

New Connections between Signaling Networks

We specifically show that four major regulators of filamentous growth are also required for FG pathway signaling (Figure 5E). The connections between the RIM101, OPI1, and RTG pathways to FG pathway regulation are entirely novel. We further show that the RAS pathway and several other pathways [MAPK, Swi4p, Rpd3p(L)] converge on the promoter of the key upstream regulator (MSB2) of the FG pathway. Like other signal integration mechanisms [8],[66], the MSB2 promoter is a target “hub” where multiple pathways converge. This regulatory point makes sense from the perspective that Msb2p levels dictate FG pathway activity [28]. Given that the FG pathway exhibits multimodality in regulation of pathway outputs [39], its precise modulation is critical to induce an appropriate response.

The regulation of the FG pathway differs from that of a related MAPK pathway, the pheromone response pathway, where secreted peptide pheromones provide the single major input into activation [5],[106],[107]. The pheromone response pathway is not regulated by the RAS, RIM, or RTG pathways and does not appear to be influenced by the Rpd3p(L) HDAC, although some target mating genes do require Rpd3p(L) for expression [100]. Both the FG and mating pathways are regulated by positive feedback [28],[65],[108],[109], presumably to provide signal amplification. Therefore, the FG pathway is distinguished in that it is highly sensitized to multiple external inputs. Because our screening approach was highly biased to identify regulators that function at the “top” of the pathway (at Msb2p), it is likely that the FG pathway may be subject to additional regulation not identified by this approach.

The networks that regulate filamentation signaling pathways appear in some cases to be redundant. For example, RAS regulates FLO11 expression through Flo8p and the FG pathway (Figure 5E). RIM101 similarly controls FLO11 expression through Nrg1p/Nrg2p and FG regulation (Figure 5E). However, any one of the major filametation regulatory pathways when absent appears fully defective for the response. Such parallel processing of signaling networks might allow for “fine-tuning” of the differentiation response, or alternatively to synchronize all of the pathways to the global regulatory circuit. Such synchronization may coordinate different aspects of filamentous growth (cell-cell adhesion, cell cycle regulation, reorganization of polarity) into a cohesive response.

RAS/cAMP Sensitizes MAPK Activity to Cellular Nutrient Status

Filamentous growth occurs within a narrow nutritional range [25], between high nutrient levels that support vegetative growth and limiting nutrients that force entry into stationary phase. The finding that Ras2p controls the overall levels of MSB2 expression extends the initial connection between RAS and the FG pathway [61] in several important ways. First, the results explain how Ras2p connects to the FG pathway above Cdc42p. Second, the data provide a link between nutrition and FG pathway signaling at the level of cellular cAMP levels. Third, Ras2p does not appear to function as a component of the FG pathway. This conclusion is based on the conditional requirement for Ras2p in MSB2 regulation, the suppression of the ras2Δ signaling defect by loss of PDE2, and the placement of Ras2p above MSB2 in the FG pathway. Our results fit with the general idea that RAS controls a broad response to cellular stress that encompasses FG pathway regulation. Ras2p has recently been shown to regulate the MAPK pathway that controls sporulation [110], a diploid-specific starvation response. Ras2p may therefore function as a general regulator of MAPK signaling in response to nutritional stress.

HDAC Regulation of MAPK Signaling

Examples by which MAPK pathways control target gene expression by recruitment of chromatin remodeling proteins is relatively common and include Rpd3p(L) regulation of HOG [99],[111],[112] and mating pathway [100] target genes. However, the regulation of MAPK activity through chromatin remodeling proteins provides a hierarchical mechanism for global cellular reprogramming. Regulation of FG pathway activity by Rpd3p(L) may contribute to the establishment of a differentiated state. Once activated, FG pathway activity may be sustained by Rpd3p(L) to reinforce accessibility to the MSB2 promoter and formation of the filamentous cell type. Although the connection between Rpd3p(L) and nutrition is not entirely clear, Rpd3p(L) preferentially localizes to highly expressed genes, such as those required for anabolic processes [113]. Therefore, Rpd3p(L) may coordinate overall growth rate with the persistence of MAPK activity. Precedent for Rpd3p(L) HDACs in regulating developmental transitions comes from Drosophila DRpd3, which together with the Chameau HAT function as opposing cofactors of JNK/AP-1-dependent transcription during metamorphosis [114]. HDAC regulation of MAPK activity may therefore represent a general feature of MAPK regulation.

In conclusion, we have identified an unprecedented degree of regulation of a differentiation-dependent MAPK pathway by multiple regulatory proteins and pathways. Our findings open up new avenues for exploring the relationships between pathways and the extent of their cross-regulation with the ultimate goal of understanding all functionally relevant pathway interactions in a comprehensive manner.

Materials and Methods

Strains, Plasmids, and Microbiological Techniques

Yeast strains are described in Table S1. Plasmids are described in Table S2. Yeast and bacterial strains were manipulated by standard methods [115],[116]. PCR-based methods were used to generate gene disruptions, GAL1 promoter fusions [117],[118], and insertion of epitope fusions [119], using auxotrophic and antibiotic resistant markers [120]. Integrations were confirmed by PCR Southern analysis and DNA sequencing. Plasmids pMSB2-GFP and pMSB2-HA have been described [31], as have plasmids pMSB2-lacZ and pMSB2AG-lacZ [39]. Plasmids containing FG pathway targets KSS1, SVS1, PGU1, and YLR042C fused to the lacZ gene were provided by C. Boone [65]. pFLO8 was provided by G. Fink [37]. Plasmid pIL30-URA3 containing FgTy-lacZ was provided by B. Errede [121], and pFRE-lacZ was provided by H. Madhani [16]. The positions of the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope fusions were 500 amino acid residues for the Msb2p protein [31], at 1015 residues for the Flo11p protein [41], and at 1000 residues for the Hkr1p protein [39].

The single cell invasive growth assay [25] and the plate-washing assay [14] were performed to assess filamentous growth. Budding pattern was based on established methodology [122], and confirmed for some experiments by visual inspection of connected cells [25]. Halo assays were performed as described [123]. Microbial mat assays were performed as described [105] by growing cells on low-agar (0.3%) YEPD medium. Oleate medium was derived from standard synthetic medium lacking amino acids that was supplemented with 0.1% yeast extract, 0.5% potassium phosphate pH 6.0, and oleic acid (Toyko Kasei Kogyo Co. TCI) at a final concentration of 0.125% (w/v) solubilized in 0.5% Tween-20. Antimycin A, from Streptomyces sp. (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used at 3 µg/ml. Oligomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used at 3 µg/ml, and rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich) was added at 20 ng/ml. β-galactosidase assays were performed as previously described [124]. For some experiments, β-galactosidase assays were performed in 96-well format by growing cells containing the MSB2-lacZ reporter to saturation in synthetic medium lacking uracil (SD–URA) to maintain selection for the plasmid in 96-well plates at 30°C. Inductions were performed in duplicate, and the average of at least two independent experiments is reported. All experiments were carried out at 30°C unless otherwise indicated.

Secretion Profiling of Msb2p

The MATa haploid deletion collection [35] was transformed with a plasmid carrying a functional hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged MSB2 gene (pMSB2-HA; [31]) using a high-throughput microtiter plate transformation protocol [125]. The deletion collection was manipulated with the BioMek 2000 automated workstation (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton CA). For some experiments, a 96-fixed pinning tool (V & P Scientific, 23 VP 408) and plate replication tool (V & P Scientific, VP 381) were used. Sterilization was performed by sequential washes in 5% bleach, distilled water, 70% ethanol, and 95% ethanol. Ethanol (5 µl of 95%) was added to each transformation mix (200 µl) to increase transformation efficiency [126]. Transformants were harvested by centrifugation in 96-well plates, resuspended in 30 µl of water, and transferred to synthetic medium containing 2% glucose and lacking uracil (SD-URA) medium in Omnitrays (VWR International Inc. Bridgeport NJ). Transformants were pinned to SD-URA for 48 h. Colonies were transferred to 96-well plates containing 100 µl of water and pinned to SD-URA medium overlaid with a nitrocellulose filter (0.4 µm; HAHY08550 Millipore) and incubated for 48 h at 30°C. Filters were rinsed in distilled water to remove cells and probed by immunoblot analysis. Cross-contamination was estimated at 0.8% based on growth in blank positions; ∼93% of the collection (4554 mutants) was examined.

For the overexpression screen, a collection of ∼5,500 overexpression plasmids [36] was examined in a wild-type Σ1278b strain containing a functional MSB2-HA gene integrated at the MSB2 locus under the control of its endogenous promoter (PC999). Plasmids were purified from Escherichia coli stocks by alkaline lysis DNA preparation in 96-well format. Plasmid DNA was transformed into PC999 using the high-throughput transformation protocol described above. Transformants were selected on SD-URA and screened by pinning to nitrocellulose filters on synthetic medium containing 2% galactose and lacking uracil (S+GAL-URA) to induce gene overexpression. Colonies were incubated for 2 days at 30°C. Filters were washed in a stream of water and probed by immunoblot analysis as described above. Candidate genes/deletions that were initially identified were confirmed by retesting. Approximately ∼35% of the deletion strains and 37% of the overexpression plasmids failed retesting and were considered false positives (Tables S3B and S4B). Comparative secretion profiling of Msb2p-HA, Hkr1p-HA, and Flo11p-HA was performed by transforming overexpression plasmids identified in the Msb2p-HA screen into strains that contain Hkr1p-HA (PC2740) and Flo11p-HA (PC2043). Transformants were pinned onto S-GAL-URA on nitrocellulose filters. Colonies were incubated for 48h, at which time filters were rinsed and evaluated by colony immunoblot analysis. The complete deletion collection transformed with pMSB2-HA (Table S3) and overexpression collection in strain PC999 (Table S4) were frozen in aliquots at −80°C and are available upon request.

Computational Analysis

To compare levels of secreted protein between samples, spot intensity was measured and normalized to colony size. Small colonies initially scored as undersecretors and large colonies (particularly at plate corners) scored as hypersecretors were eliminated or flagged for retesting. As an additional test, standard immunoblots were performed from cells grown in liquid culture. Supernatants (S) and cell pellets (P) were separated by centrifugation. In most cases (>80%), differential secretion by colony immunoblot was reflected by an altered S/P ratio by standard immunoblot analysis. The ImageJ MicroArray Profile.jar algorithm (http://www.optinav.com/download/MicroArray_Profile.jar) created by Dr. Bob Dougherty and Dr. Wayne Rasband, commonly used for Microarray analysis, was used as a plugin for the ImageJ program. Image intensity was determined in 96-panel format by inverting the image after background subtraction. Plate-to-plate variation was normalized by dividing the average intensity of all spots with the average intensity of each plate, and this factor was applied to the intensity of each spot. Heat maps for expression and secretion profiling were generated as described [127]. Classification of genes based on process/function was determined using GO ontology terms in publicly available databases including the Saccharomyces genome database (http://www.yeastgenome.org/). Analysis of human mucin genes was facilitated by the Human Protein Reference Database (http://www.hprd.org/).

DNA Microarray Analysis

DNA microarray analysis was performed as described [128],[129]. Wild type (PC538), GAL-MSB2 (PC1083), GAL-MSB2 ste12Δ (PC1079), GAL-MSB2 ras2Δ (PC2949), MSB2Δ100–818 (PC1516), MSB2Δ100–818 ste12Δ (PC1811), and MSB2Δ100–818 ras2Δ (PC2364) strains were grown in YEP-GAL for 6 h, at which point cells were examined by microscopy for the characteristic filamentation response. RNA was prepared by hot acid phenol and passage over an RNeasy column (Qiagen). Microarray construction, target labeling, and hybridization protocols were as described [130]. Sample comparisons were independently replicated at least 3 times from separate inductions. Fluoro-reverse experiments were used to identify sequence-specific dye biases. Arrays were scanned using a GenePix 4000 scanner (Axon Instruments). Image analysis was performed using GenePix Pro 3.0. Array features (i.e., spots) having low signal intensities or signals compromised by artifacts were removed from further analysis. Background subtracted Cy5/Cy3 ratios were log2 transformed and a Loess normalization strategy (f = 0.67) was applied for each array using S-Plus (MathSoft, Cambridge, MA). Each feature where the |log2 (ratio)|≥0.8, the corresponding gene was considered differentially expressed.

Microscopy

Differential-interference-contrast (DIC) and fluorescence microscopy using the FITC filter set were performed using an Axioplan 2 fluorescent microscope (Zeiss) with a PLAN-APOCHROMAT 100X/1.4 (oil) objective (N.A. 0.17). Digital images were obtained with the Axiocam MRm camera (Zeiss). Axiovision 4.4 software (Zeiss) was used for image acquisition and analysis. For Msb2p-GFP localization, cells were grown to saturation in selective medium to maintain plasmids harboring MSB2-GFP fusions. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in YEPD medium for 4.5 h. Cells were harvested, washed three times in water, and visualized at 100X.

Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblots were performed as described [31]. To compare protein levels between strains, cells were grown to saturation in YEPD medium and subcultured into YEPD or YEP-GAL medium for 8 h. Culture volumes were adjusted to account for differences in cell number and harvested by centrifugation. Supernatant volumes were similarly adjusted. Cells were disrupted by addition of 200 µl lysis buffer (8 M Urea, 5 % SDS, 40 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 0.1 M EDTA, 0.4 mg/ml Bromophenol blue and 1 % β-mercaptoethanol) and glass beads followed by vortexing for 5 minutes at the highest setting and boiling 5 min. Supernatants were examined by boiling in 1.5 volumes of lysis buffer for 5 min. For some experiments, cells were lysed in spheroplast buffer (1.2M sorbitol, 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.4, 1 mM MgCl, 250 ug/ml of zymolyase), and protein concentration was determined by Bradford assays (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA). Equal concentrations of protein were loaded into each lane. For some experiments, blots were stripped and re-probed using anti-actin monoclonal antibodies (Chemicon; Billerica, MA). Monoclonal antibodies against the HA epitope were used (12CA5). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% or 10%–20% gradient gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (protran BA85, VWR International Inc. Bridgeport NJ). Membranes were incubated in blocking buffer (5% nonfat dry milk, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20) for 1 hr at 25°C. Nitrocellulose membranes were incubated for 18 hr at 4°C in blocking buffer containing primary antibodies. ECL Plus immunoblotting reagents were used to detect secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway NJ). Immunoblots of proteins secreted from mats were performed by growing cells on nitrocellulose filters on low-agar (0.3%) YEPD medium.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Analysis

ChIP assays were performed as described [131]. Strains PC3021 (STE12-HA), PC3353 (sin3Δ, STE12-HA) and PC3579 (SIN3-HA) were grown in YEPD medium for 8 h. Cross-linking was performed with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at 25°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation and washed twice in PBS buffer. Cells were resuspended in ChIP lysis buffer (Upstate, Billerica, CA), and lysed by Fast Prep 24 (MP) for one cycle at 6.5 for 45 sec. After puncturing the bottom of Fast Prep tubes with a 22 gauge needle, lysates were collected by centrifugation. DNA was sheared by sonication on a Branson Digital Sonifier at setting 20% amplitude, 15 pulses for 20 sec, 55 sec. rest. Pull downs were performed using a ChIP assay kit (Upstate) with anti-HA antibodies with 10% input sample set aside for a control. qPCR was used to determine relative amount of immunoprecipitated specific DNA loci in IP, Input, and Mock (no antibody) samples. The housekeeping ACT1 gene was used to normalize quantification in qPCR reactions. Data are expressed as IP/Input where ΔΔCt = (Ct IP_MSB2-Ct IP_ACT1)-(Ct Input_MSB2-Ct Input_ACT1). Primers used were MSB2 promoter forward 5′-CGATAGCTGATAGACTGTGGAGTCG-3′ and reverse 5′ - CTGGCAACGCCCGACGTGTCTAGCC-3′, MSB2 intergenic region forward 5′ - TGACCAAACTTCGACTGCTGG-3′ and reverse 5′ - AGCTGCTGATGCAGTGGTAA-3′; and ACT1 forward 5′ - GGCTTCTTTGACTACCTTCCAACA-3′ and reverse 5′ - GATGGACCACTTTCGTCGTATTC-3′. ChIP pull downs were also visualized by gel electrophoresis.

mRNA Level Determination Using Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from 25 ml cultures grown in YEP GAL for 8 h using hot acid phenol extraction. cDNA synthesis was carried out using 1 µg RNA and the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad; Hercules CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. One tenth of the synthesized cDNA was used as the template for real-time PCR. 25 ul real time PCR reactions were performed on the BioRad MyiQ Cycler with iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). RT qPCR was performed using the following amplification cycles: initial denaturation for 8 min at 95°C, followed by 35×cycle 2 (denaturation for 15 sec at 95°C and annealing for 1 min at 60°C). Melt curve data collection was enabled by decreasing the set point temperature after cycle 2 by 0.5°C. The specificity of amplicons was confirmed by generating the melt curve profile of all amplified products. Gene expression was quantified as described [132]. Primers were based on a previous report [133] and were FLO11 forward 5′ - GTTCAACCAGTCCAAGCGAAA-3′ and reverse 5′ - GTAGTTACAGGTGTGGTAGGTGAAGTG-3′and those described for ChIP assays above. All reactions were performed in duplicate and average values are reported.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. DoroquezDB

RebayI

2006 Signal integration during development: mechanisms of EGFR and Notch pathway function and cross-talk. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 41 339 385

2. HurlbutGD

KankelMW

LakeRJ

Artavanis-TsakonasS

2007 Crossing paths with Notch in the hyper-network. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19 166 175

3. WagnerEF

NebredaAR

2009 Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer 9 537 549

4. GimenoCJ

LjungdahlPO

StylesCA

FinkGR

1992 Unipolar cell divisions in the yeast S. cerevisiae lead to filamentous growth: regulation by starvation and RAS. Cell 68 1077 1090

5. SchwartzMA

MadhaniHD

2004 Principles of map kinase signaling specificity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Genet 38 725 748

6. VerstrepenKJ

KlisFM

2006 Flocculation, adhesion and biofilm formation in yeasts. Mol Microbiol 60 5 15

7. JinR

DobryCJ

McCownPJ

KumarA

2008 Large-scale analysis of yeast filamentous growth by systematic gene disruption and overexpression. Mol Biol Cell 19 284 296

8. BornemanAR

Leigh-BellJA

YuH

BertoneP

GersteinM

2006 Target hub proteins serve as master regulators of development in yeast. Genes Dev 20 435 448

9. PrinzS

Avila-CampilloI

AldridgeC

SrinivasanA

DimitrovK

2004 Control of yeast filamentous-form growth by modules in an integrated molecular network. Genome Res 14 380 390

10. MadhaniHD

GalitskiT

LanderES

FinkGR

1999 Effectors of a developmental mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade revealed by expression signatures of signaling mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 12530 12535

11. LoHJ

KohlerJR

DiDomenicoB

LoebenbergD

CacciapuotiA

1997 Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90 939 949

12. WhitewayM

BachewichC

2007 Morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Annu Rev Microbiol 61 529 553

13. NobileCJ

MitchellAP

2006 Genetics and genomics of Candida albicans biofilm formation. Cell Microbiol 8 1382 1391

14. RobertsRL

FinkGR

1994 Elements of a single MAP kinase cascade in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mediate two developmental programs in the same cell type: mating and invasive growth. Genes Dev 8 2974 2985

15. MadhaniHD

FinkGR

1997 Combinatorial control required for the specificity of yeast MAPK signaling. Science 275 1314 1317

16. MadhaniHD

StylesCA

FinkGR

1997 MAP kinases with distinct inhibitory functions impart signaling specificity during yeast differentiation. Cell 91 673 684

17. MoschHU

KublerE

KrappmannS

FinkGR

BrausGH

1999 Crosstalk between the Ras2p-controlled mitogen-activated protein kinase and cAMP pathways during invasive growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 10 1325 1335

18. VinodPK

SenguptaN

BhatPJ

VenkateshKV

2008 Integration of global signaling pathways, cAMP-PKA, MAPK and TOR in the regulation of FLO11. PLoS ONE 3 e1663 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001663

19. LambTM

MitchellAP

2003 The transcription factor Rim101p governs ion tolerance and cell differentiation by direct repression of the regulatory genes NRG1 and SMP1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 23 677 686

20. BarwellKJ

BoysenJH

XuW

MitchellAP

2005 Relationship of DFG16 to the Rim101p pH response pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 4 890 899

21. RothfelsK

TannyJC

MolnarE

FriesenH

CommissoC

2005 Components of the ESCRT pathway, DFG16, and YGR122w are required for Rim101 to act as a corepressor with Nrg1 at the negative regulatory element of the DIT1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 25 6772 6788

22. ReynoldsTB

2006 The Opi1p transcription factor affects expression of FLO11, mat formation, and invasive growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot Cell 5 1266 1275

23. KuchinS

VyasVK

CarlsonM

2002 Snf1 protein kinase and the repressors Nrg1 and Nrg2 regulate FLO11, haploid invasive growth, and diploid pseudohyphal differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 22 3994 4000

24. KuchinS

VyasVK

CarlsonM

2003 Role of the yeast Snf1 protein kinase in invasive growth. Biochem Soc Trans 31 175 177

25. CullenPJ

SpragueGFJr

2000 Glucose depletion causes haploid invasive growth in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 13619 13624

26. PalecekSP

ParikhAS

KronSJ

2000 Genetic analysis reveals that FLO11 upregulation and cell polarization independently regulate invasive growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 156 1005 1023

27. MoschHU

FinkGR

1997 Dissection of filamentous growth by transposon mutagenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 145 671 684

28. CullenPJ

SabbaghWJr

GrahamE

IrickMM

van OldenEK

2004 A signaling mucin at the head of the Cdc42 - and MAPK-dependent filamentous growth pathway in yeast. Genes Dev 18 1695 1708

29. SinghPK

HollingsworthMA

2006 Cell surface-associated mucins in signal transduction. Trends Cell Biol 16 467 476

30. ParkHO

BiE

2007 Central roles of small GTPases in the development of cell polarity in yeast and beyond. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71 48 96

31. VadaieN

DionneH

AkajagborDS

NickersonSR

KrysanDJ

2008 Cleavage of the signaling mucin Msb2 by the aspartyl protease Yps1 is required for MAPK activation in yeast. J Cell Biol 181 1073 1081

32. RobertsCJ

RaymondCK

YamashiroCT

StevensTH

1991 Methods for studying the yeast vacuole. Methods Enzymol 194 644 661

33. SchluterC

LamKK

BrummJ

WuBW

SaundersM

2008 Global Analysis of Yeast Endosomal Transport Identifies the Vps55/68 Sorting Complex. Mol Biol Cell 19 1282 1294

34. BonangelinoCJ

ChavezEM

BonifacinoJS

2002 Genomic screen for vacuolar protein sorting genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 13 2486 2501

35. WinzelerEA

ShoemakerDD

AstromoffA

LiangH

AndersonK

1999 Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285 901 906

36. GelperinDM

WhiteMA

WilkinsonML

KonY

KungLA

2005 Biochemical and genetic analysis of the yeast proteome with a movable ORF collection. Genes Dev 19 2816 2826

37. LiuH

StylesCA

FinkGR

1996 Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C has a mutation in FLO8, a gene required for filamentous growth. Genetics 144 967 978

38. NiuW

LiZ

ZhanW

IyerVR

MarcotteEM

2008 Mechanisms of cell cycle control revealed by a systematic and quantitative overexpression screen in S. cerevisiae. PLoS Genet 4 e1000120 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000120

39. PitoniakA

BirkayaB

DionneHS

VadiaeN

CullenPJ

2009 The Signaling Mucins Msb2 and Hkr1 Differentially Regulate the Filamentation MAPK Pathway and Contribute to a Multimodal Response. Mol Biol Cell

40. TatebayashiK

TanakaK

YangHY

YamamotoK

MatsushitaY

2007 Transmembrane mucins Hkr1 and Msb2 are putative osmosensors in the SHO1 branch of yeast HOG pathway. Embo J 26 3521 3533

41. KarunanithiSR

VadaieN

BirkayaB

DionneHM

JoshiJ

(SUBMITTED) Regulation and Functional Basis of Mucin Shedding in a Unicellular Eukaryote.

42. GuoB

StylesCA

FengQ

FinkGR

2000 A Saccharomyces gene family involved in invasive growth, cell-cell adhesion, and mating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 12158 12163

43. KrysanDJ

TingEL

AbeijonC

KroosL

FullerRS

2005 Yapsins are a family of aspartyl proteases required for cell wall integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot Cell 4 1364 1374

44. AndrewsBJ

HerskowitzI

1989 The yeast SWI4 protein contains a motif present in developmental regulators and is part of a complex involved in cell-cycle-dependent transcription. Nature 342 830 833

45. BreedenL

MikesellGE

1991 Cell cycle-specific expression of the SWI4 transcription factor is required for the cell cycle regulation of HO transcription. Genes Dev 5 1183 1190

46. NasmythK

DirickL

1991 The role of SWI4 and SWI6 in the activity of G1 cyclins in yeast. Cell 66 995 1013

47. OgasJ

AndrewsBJ

HerskowitzI

1991 Transcriptional activation of CLN1, CLN2, and a putative new G1 cyclin (HCS26) by SWI4, a positive regulator of G1-specific transcription. Cell 66 1015 1026

48. BaetzK

AndrewsB

1999 Regulation of cell cycle transcription factor Swi4 through auto-inhibition of DNA binding. Mol Cell Biol 19 6729 6741

49. BeanJM

SiggiaED

CrossFR

2005 High functional overlap between MluI cell-cycle box binding factor and Swi4/6 cell-cycle box binding factor in the G1/S transcriptional program in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 171 49 61

50. BardwellL

2006 Mechanisms of MAPK signalling specificity. Biochem Soc Trans 34 837 841

51. AbdullahU

CullenPJ

2009 The tRNA modification complex elongator regulates the Cdc42-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway that controls filamentous growth in yeast. Eukaryot Cell 8 1362 1372

52. JiaY

RothermelB

ThorntonJ

ButowRA

1997 A basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper transcription complex in yeast functions in a signaling pathway from mitochondria to the nucleus. Mol Cell Biol 17 1110 1117

53. DilovaI

AronovaS

ChenJC

PowersT

2004 Tor signaling and nutrient-based signals converge on Mks1p phosphorylation to regulate expression of Rtg1.Rtg3p-dependent target genes. J Biol Chem 279 46527 46535

54. Ferreira JuniorJR

SpirekM

LiuZ

ButowRA

2005 Interaction between Rtg2p and Mks1p in the regulation of the RTG pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 354 2 8

55. LiuZ

SekitoT

EpsteinCB

ButowRA

2001 RTG-dependent mitochondria to nucleus signaling is negatively regulated by the seven WD-repeat protein Lst8p. Embo J 20 7209 7219

56. GiannattasioS

LiuZ

ThorntonJ

ButowRA

2005 Retrograde response to mitochondrial dysfunction is separable from TOR1/2 regulation of retrograde gene expression. J Biol Chem 280 42528 42535

57. KligLS

HomannMJ

CarmanGM

HenrySA

1985 Coordinate regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: pleiotropically constitutive opi1 mutant. J Bacteriol 162 1135 1141

58. WhiteMJ

HirschJP

HenrySA

1991 The OPI1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a negative regulator of phospholipid biosynthesis, encodes a protein containing polyglutamine tracts and a leucine zipper. J Biol Chem 266 863 872

59. VothWP

YuY

TakahataS

KretschmannKL

LiebJD

2007 Forkhead proteins control the outcome of transcription factor binding by antiactivation. Embo J 26 4324 4334

60. KimTS

LeeSB

KangHS

2004 Glucose repression of STA1 expression is mediated by the Nrg1 and Sfl1 repressors and the Srb8-11 complex. Mol Cell Biol 24 7695 7706

61. MoschHU

RobertsRL

FinkGR

1996 Ras2 signals via the Cdc42/Ste20/mitogen-activated protein kinase module to induce filamentous growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93 5352 5356

62. CarterGW

RuppS

FinkGR

GalitskiT

2006 Disentangling information flow in the Ras-cAMP signaling network. Genome Res 16 520 526

63. RobertsonLS

CaustonHC

YoungRA

FinkGR

2000 The yeast A kinases differentially regulate iron uptake and respiratory function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 5984 5988

64. ZamanS

LippmanSI

SchneperL

SlonimN

BroachJR

2009 Glucose regulates transcription in yeast through a network of signaling pathways. Mol Syst Biol 5 245

65. RobertsCJ

NelsonB

MartonMJ

StoughtonR

MeyerMR

2000 Signaling and circuitry of multiple MAPK pathways revealed by a matrix of global gene expression profiles. Science 287 873 880

66. RuppS

SummersE

LoHJ

MadhaniH

FinkG

1999 MAP kinase and cAMP filamentation signaling pathways converge on the unusually large promoter of the yeast FLO11 gene. Embo J 18 1257 1269

67. ZamanS

LippmanSI

ZhaoX

BroachJR

2008 How Saccharomyces Responds to Nutrients. Annu Rev Genet

68. SantangeloGM

2006 Glucose signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70 253 282

69. Boy-MarcotteE

IkonomiP

JacquetM

1996 SDC25, a dispensable Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae differs from CDC25 by its regulation. Mol Biol Cell 7 529 539

70. PoulletP

CrechetJB

BernardiA

ParmeggianiA

1995 Properties of the catalytic domain of sdc25p, a yeast GDP/GTP exchange factor of Ras proteins. Complexation with wild-type Ras2p, [S24N]Ras2p and [R80D, N81D]Ras2p. Eur J Biochem 227 537 544

71. TodaT

UnoI

IshikawaT

PowersS

KataokaT

1985 In yeast, RAS proteins are controlling elements of adenylate cyclase. Cell 40 27 36

72. SassP

FieldJ

NikawaJ

TodaT

WiglerM

1986 Cloning and characterization of the high-affinity cAMP phosphodiesterase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83 9303 9307

73. PanX

HeitmanJ

1999 Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase regulates pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 19 4874 4887

74. van DykD

PretoriusIS

BauerFF

2005 Mss11p is a central element of the regulatory network that controls FLO11 expression and invasive growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 169 91 106

75. RobertsonLS

FinkGR

1998 The three yeast A kinases have specific signaling functions in pseudohyphal growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 13783 13787

76. LorenzMC

PanX

HarashimaT

CardenasME

XueY

2000 The G protein-coupled receptor gpr1 is a nutrient sensor that regulates pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 154 609 622

77. LemaireK

Van de VeldeS

Van DijckP

TheveleinJM

2004 Glucose and Sucrose Act as Agonist and Mannose as Antagonist Ligands of the G Protein-Coupled Receptor Gpr1 in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell 16 293 299

78. HarashimaT

AndersonS

YatesJR3rd

HeitmanJ

2006 The kelch proteins Gpb1 and Gpb2 inhibit Ras activity via association with the yeast RasGAP neurofibromin homologs Ira1 and Ira2. Mol Cell 22 819 830

79. PeetersT

LouwetW

GeladeR

NauwelaersD

TheveleinJM

2006 Kelch-repeat proteins interacting with the Galpha protein Gpa2 bypass adenylate cyclase for direct regulation of protein kinase A in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 13034 13039

80. HarashimaT

HeitmanJ

2002 The Galpha protein Gpa2 controls yeast differentiation by interacting with kelch repeat proteins that mimic Gbeta subunits. Mol Cell 10 163 173

81. BroachJR

1991 RAS genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: signal transduction in search of a pathway. Trends Genet 7 28 33

82. CharizanisC

JuhnkeH

KremsB

EntianKD

1999 The oxidative stress response mediated via Pos9/Skn7 is negatively regulated by the Ras/PKA pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet 261 740 752

83. HasanR

LeroyC

IsnardAD

LabarreJ

Boy-MarcotteE

2002 The control of the yeast H2O2 response by the Msn2/4 transcription factors. Mol Microbiol 45 233 241

84. FabrizioP

LiouLL

MoyVN

DiasproA

ValentineJS

2003 SOD2 functions downstream of Sch9 to extend longevity in yeast. Genetics 163 35 46

85. LongoVD

EllerbyLM

BredesenDE

ValentineJS

GrallaEB

1997 Human Bcl-2 reverses survival defects in yeast lacking superoxide dismutase and delays death of wild-type yeast. J Cell Biol 137 1581 1588

86. SinclairD

MillsK

GuarenteL

1998 Aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Microbiol 52 533 560

87. IgualJC

NavarroB

1996 Respiration and low cAMP-dependent protein kinase activity are required for high-level expression of the peroxisomal thiolase gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet 252 446 455

88. RundlettSE

CarmenAA

KobayashiR

BavykinS

TurnerBM

1996 HDA1 and RPD3 are members of distinct yeast histone deacetylase complexes that regulate silencing and transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93 14503 14508

89. KadoshD

StruhlK

1997 Repression by Ume6 involves recruitment of a complex containing Sin3 corepressor and Rpd3 histone deacetylase to target promoters. Cell 89 365 371

90. KastenMM

DorlandS

StillmanDJ

1997 A large protein complex containing the yeast Sin3p and Rpd3p transcriptional regulators. Mol Cell Biol 17 4852 4858

91. LechnerT

CarrozzaMJ

YuY

GrantPA

EberharterA

2000 Sds3 (suppressor of defective silencing 3) is an integral component of the yeast Sin3[middle dot]Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex and is required for histone deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem 275 40961 40966

92. CarrozzaMJ

LiB

FlorensL

SuganumaT

SwansonSK

2005 Histone H3 methylation by Set2 directs deacetylation of coding regions by Rpd3S to suppress spurious intragenic transcription. Cell 123 581 592

93. ColinaAR

YoungD

2005 Raf60, a novel component of the Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex required for Rpd3 activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 280 42552 42556

94. QiM

ElionEA

2005 MAP kinase pathways. J Cell Sci 118 3569 3572

95. MurphyLO

BlenisJ

2006 MAPK signal specificity: the right place at the right time. Trends Biochem Sci 31 268 275

96. CookJG

BardwellL

KronSJ

ThornerJ

1996 Two novel targets of the MAP kinase Kss1 are negative regulators of invasive growth in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 10 2831 2848

97. OlsonKA

NelsonC

TaiG

HungW

YongC

2000 Two regulators of Ste12p inhibit pheromone-responsive transcription by separate mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol 20 4199 4209

98. ChouS

LaneS

LiuH

2006 Regulation of mating and filamentation genes by two distinct Ste12 complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 26 4794 4805

99. De NadalE

ZapaterM

AlepuzPM

SumoyL

MasG

2004 The MAPK Hog1 recruits Rpd3 histone deacetylase to activate osmoresponsive genes. Nature 427 370 374

100. VidalM

StrichR

EspositoRE

GaberRF

1991 RPD1 (SIN3/UME4) is required for maximal activation and repression of diverse yeast genes. Mol Cell Biol 11 6306 6316

101. BarralesRR

JimenezJ

IbeasJI

2008 Identification of novel activation mechanisms for FLO11 regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 178 145 156

102. LoWS

DranginisAM

1996 FLO11, a yeast gene related to the STA genes, encodes a novel cell surface flocculin. J Bacteriol 178 7144 7151

103. LambrechtsMG

BauerFF

MarmurJ

PretoriusIS

1996 Muc1, a mucin-like protein that is regulated by Mss10, is critical for pseudohyphal differentiation in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93 8419 8424

104. LoWS

DranginisAM

1998 The cell surface flocculin Flo11 is required for pseudohyphae formation and invasion by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 9 161 171

105. ReynoldsTB

FinkGR

2001 Bakers' yeast, a model for fungal biofilm formation. Science 291 878 881

106. BardwellL

2004 A walk-through of the yeast mating pheromone response pathway. Peptides 25 1465 1476

107. ElionEA

2000 Pheromone response, mating and cell biology. Curr Opin Microbiol 3 573 581

108. NakayamaN

MiyajimaA

AraiK

1987 Common signal transduction system shared by STE2 and STE3 in haploid cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: autocrine cell-cycle arrest results from forced expression of STE2. Embo J 6 249 254

109. BenderA

SpragueGFJr

1986 Yeast peptide pheromones, a-factor and alpha-factor, activate a common response mechanism in their target cells. Cell 47 929 937

110. McDonaldCM

WagnerM

DunhamMJ

ShinME

AhmedNT

2009 The Ras/cAMP pathway and the CDK-like kinase Ime2 regulate the MAPK Smk1 and spore morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 181 511 523

111. MasG

de NadalE

DechantR

de la ConcepcionML

LogieC

2009 Recruitment of a chromatin remodelling complex by the Hog1 MAP kinase to stress genes. Embo J 28 326 336

112. DunnKL

EspinoPS

DrobicB

HeS

DavieJR

2005 The Ras-MAPK signal transduction pathway, cancer and chromatin remodeling. Biochem Cell Biol 83 1 14

113. KurdistaniSK

RobyrD

TavazoieS

GrunsteinM

2002 Genome-wide binding map of the histone deacetylase Rpd3 in yeast. Nat Genet 31 248 254

114. MiottoB

SagnierT

BerengerH

BohmannD

PradelJ

2006 Chameau HAT and DRpd3 HDAC function as antagonistic cofactors of JNK/AP-1-dependent transcription during Drosophila metamorphosis. Genes Dev 20 101 112

115. SambrookJ

FritschEF

ManiatisT

1989 Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

116. RoseMD

WinstonF

HieterP

1990 Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

117. BaudinA

Ozier-KalogeropoulosO

DenouelA

LacrouteF

CullinC

1993 A simple and efficient method for direct gene deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res 21 3329 3330

118. LongtineMS

McKenzieA3rd

DemariniDJ

ShahNG

WachA

1998 Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14 953 961

119. SchneiderBL

SeufertW

SteinerB

YangQH

FutcherAB

1995 Use of polymerase chain reaction epitope tagging for protein tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 11 1265 1274

120. GoldsteinAL

McCuskerJH

1999 Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15 1541 1553

121. LalouxI

JacobsE

DuboisE

1994 Involvement of SRE element of Ty1 transposon in TEC1-dependent transcriptional activation. Nucleic Acids Res 22 999 1005

122. ChantJ

PringleJR

1995 Patterns of bud-site selection in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 129 751 765

123. JennessDD

GoldmanBS

HartwellLH

1987 Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants unresponsive to alpha-factor pheromone: alpha-factor binding and extragenic suppression. Mol Cell Biol 7 1311 1319

124. CullenPJ

SchultzJ

HoreckaJ

StevensonBJ

JigamiY

2000 Defects in protein glycosylation cause SHO1-dependent activation of a STE12 signaling pathway in yeast. Genetics 155 1005 1018

125. GietzRD

SchiestlRH

2007 Microtiter plate transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat Protoc 2 5 8

126. GietzRD

WoodsRA

2002 Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol 350 87 96

127. EisenMB

SpellmanPT

BrownPO

BotsteinD

1998 Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 14863 14868

128. DeRisiJL

IyerVR

BrownPO

1997 Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science 278 680 686

129. LashkariDA

DeRisiJL

McCuskerJH

NamathAF

GentileC

1997 Yeast microarrays for genome wide parallel genetic and gene expression analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94 13057 13062

130. FazzioTG

KooperbergC

GoldmarkJP

NealC

BasomR

2001 Widespread collaboration of Isw2 and Sin3-Rpd3 chromatin remodeling complexes in transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol 21 6450 6460

131. YuMC

LammingDW

EskinJA

SinclairDA

SilverPA