-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Stability of orthognatic surgery in cleft lip and palate patients

Authors: V. Placák 1,2; K. Malá 1,2; Jiří Borovec 1,2,3

; M. Drahoš 4; P. Švihlíková-Poláčková 3; Wanda Urbanová 3

Authors place of work: Oddělení ústní, čelistní a obličejové chirurgie, Masarykova nemocnice, Ústí nad Labem 1; Stomatologická klinika, Lékařská fakulta Univerzity Karlovy a Fakultní nemocnice, Plzeň 2; Stomatologická klinika, 3. lékařská fakulta Univerzity Karlovy a Fakultní nemocnice Královské Vinohrady, Praha 3; Ústav biofyziky a informatiky, 1. lékařská fakulta Univerzity Karlovy, Praha 4

Published in the journal: Česká stomatologie / Praktické zubní lékařství, ročník 120, 2020, 2, s. 43-49

Category: Původní práce

Summary

Introduction: Cleft lip and palate patients have often hypoplasia of midfacial area. Orthognathic surgery is often necessary to achieve good facial aesthetics and functional occlusion. The aim of this study is to evaluate maxillary stability after Le Fort I osteotomy in cleft lip and palate patients.

Methods: Five patients, two women and three men, 17–22 years old with unilateral cleft lip and palate underwent comprehensive orthodontic and surgery treatment. The orthodontic treatment was performed at the Department of Orthodontics and Cleft Anomalies, University Hospital Královské Vinohrady and Le Fort I osteotomy at the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery in Masaryk Hospital, Ústí nad Labem. Maxillary stability after orthognathic surgery were measured at cephalograms, which were taken before (T1), first day after the surgery (T2) and 20 months after the procedure on average (T3). The position of maxilla was determined by measuring the SNA angle and horizontal and vertical position of the A point. Frankfort horizontal plane (FH) and line perpendicular to the FH from Porion point (Y), which were drawn on each cephalogram. Vertical dimension was measured as a distance between A point and FH (AX) and horizontal dimension as a distance between A point and the perpendicular line to FH (AY). All values were measured twice in four weeks interval by one evaluator and average values were used to eliminate measurement errors.

Results: The SNA angle increased of 5.6° on average in all five patients after surgery, horizontal shift of the point A was 10.7 mm. The relapse was 4.7° in SNA angle and -7.1 mm in point A with major differences among patients. Vertical position of A point was changed by -3,4 mm on average after surgery. In some patients AX distance has grown, in some cases has shortened. Vertical position of A point has changed with high interindividual changes during period after surgery.

Conclusion: The maxillary advancement Le Fort I in cleft lip and palate patients is not stable; relapse can be expected. The relapse rate is individual, probably caused by tissue retraction in the original scars or newly formed scar tissue, or by tension of surrounding soft tissues. However, the final occlusion is satisfactory in long-term period according to our experience. More detailed research should be done to determine causes and to investigate the extent of relapse.

Keywords:

cleft lip and palate – pseudoprogenia – Le Fort I – orthognathic surgery

INTRODUCTION

Cleft lip, alveolar process and/or palate is the most frequent congenital developmental defect of the face compatible with life. The anomaly has different extent – from unilateral cleft lip or isolated cleft palate to total bilateral cleft lip, alveolar process and palate.

The incidence of cleft lip and palate in the Czech Republic is one per 534 of life born children [1]. This developmental defect occurs in time period between 5th and 12th week of intrauteral development. The medionasal and maxillary processes on the first pharyngeal arch fail to join to some extent. Both qualitative and quantitative defect origins, which requires care of team of specialists in a center focused on this problem. Such care usually lasts for the whole childhood and adolescence of the patient [2].

The etiology of cleft lip and palate is nowadays considered multifactorial. Genetic factors are known in approximately one third of the patients. In others the cleft defect of the maxilla is caused by a combination of genetic predisposition and impact of external factors. Only small part of these defects is attributed solely to environmental factors or teratogens, such as medicaments intake, alcohol abuse, smoking and fever in critical phases of fetal development [3, 4].

There are different classifications of the orofacial clefts. The Burian`s classification is generally accepted in the Czech Republic. However, it is rather complicated for a practical usage. Thus, the Department of Orthodontics and Cleft Anomalies (Charles University, 3rd Faculty of Medicine, and University Hospital Královské Vinohrady) uses the LASHSAL classification according to Kriens [5], which enables a fast orientation in the extent and localization of the cleft (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Schematic visualization of the Kriens classification LAHSHAL [5].

Capital letter means complete cleft, lowercase letter an incomplete cleft.

L – lip right, A – alveolus right, H – hard palate right, S – soft palate (median), hard palate left – H, alveolus left – A, lip left – L.![Schematic visualization of the Kriens classification LAHSHAL [5].<br>

Capital letter means complete cleft, lowercase letter an incomplete cleft.<br>

L – lip right, A – alveolus right, H – hard palate right, S – soft palate (median), hard palate left – H, alveolus left – A, lip left – L.](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image_pdf/a220026b4b1a582a7c71bf06a0fb0476.jpeg)

The orofacial cleft is both qualitative and quantitative defect. From the wide spectrum of symptoms it is worth mentioning the disorder of development of the upper dental lamina and resulting changes in numbers and shapes of teeth. This relates mostly, but not exclusively, to upper lateral incisors in the area of the cleft. Other problems involve persisting oronasal communication in some patients; chronic otitis often leading into a hearing impairment; improper air flowing in nasal and oral cavity and voice production and modulation. Further, disorder of growth and development of the upper jaw can be often diagnosed resulting in the hypoplasia of midface and originating in pseudoprogenic profile (Fig. 2A) [6]. This is based on smaller growth potential of the clefted upper jaw in combination with scars after previous surgeries.

Fig. 2. (A, B). (A) Pseudoprogenic profile, based on midfacial hypoplasia in patient with unilateral cleft lip and palate before orthognathic surgery. (B) Esthetic improvement in the same patient after the orthognathic surgery (Department of Orthodontics and Cleft Anomalies FNKV and CU, 3rd FM, Prague).

Several therapeutic approaches can be used for a correction of the maxillary hypoplasia and face esthetic improvement. During the growth and the pubertal growth spurt it is possible to use orthognathic surgical techniques with spreading of the upper jaw in transversal direction using fixed palatal expander in combination with surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion (SARME). The vertical and sagittal growth of the upper jaw are promoted by face masks and extraoral expanders. Bone-anchored maxillary protraction using intraoral elastics anchored on Bollard miniplates can be also used in suitable cases [7]. Later on, with the skeletal growth finished and after appropriate orthodontic pretreatment the correction of the upper jaw`s position can be done by Le Fort I osteotomy and subsequent ventral maxillary displacement, either gradually by the distractor or immediately during the orthognathic surgery (Fig. 2B) [8].

The aim of this study is to evaluate maxillary stability at least one year after Le Fort I osteotomy in unilateral cleft lip and palate patients with finished growth.

METHODOLOGY

Two women and three men were included in this study with unilateral cleft lip, alveolar process and palate. The age ranged from 17 to 22 years. All the patients were treated in the Cleft center of the University Hospital Královské Vinohrady in Prague. They underwent primary surgical corrections at the Department of Plastic Surgery of the same hospital according to the standard treatment protocol: upper lip reconstruction in three months of age, palate closing in nine months of age and maxillary alveolar process reconstruction, i.e. bone grafting with spongious bone in nine years of age. Orthodontic pretreatment and posttreatment were performed at the Department of Orthodontics and Cleft Anomalies, University Hospital Královské Vinohrady. The maxillary advancement in Le Fort I line was carried out at the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery in Masaryk Hospital, Ústí nad Labem. The orthognathic surgery was done by one experienced operator in all our patients.

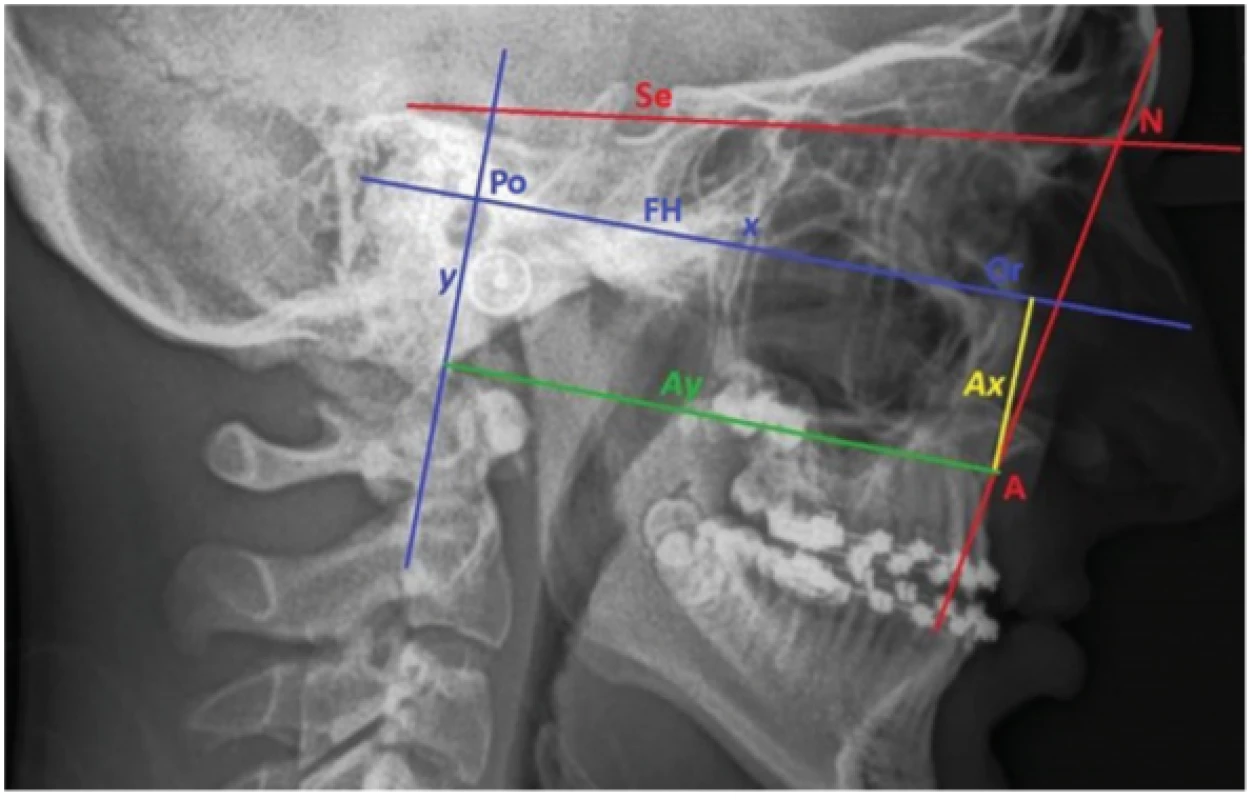

The upper jaw positions were measured in cephalograms to assess the relapse extent using the method presented by Young et al. [9]. In each patient the cephalograms were taken before the surgery (T1), in first few days after the surgery (T2), and one to three years (average 20 months – see tab. 1) after the surgery (T3). The following points were marked on the cephalograms in the software PC Dent: Sella (in the middle of sella turcica; Se), A (most dorsal point at the front contour of upper alveolar processus), Porion (upper margin of porus acusticus externus; Po), Orbitale (lower point of orbital margin; Or). The Frankfurt horizontal line was reconstructed (running through Po and Or; FH) and a line perpendicular to FH in point Po was drawn (Y). In all cephalograms the SNA angle and position of A point from FH and Y were measured (Fig. 3). Vertical dimension was measured as a distance between A point and FH (AX) and horizontal dimension as a distance between A point and the perpendicular line to FH (AY). All values were measured twice in four weeks interval by one evaluator and average values were used to eliminate measurement errors.

Fig. 3. T1 – Cephalogram of patient with unilateral cleft lip and palate before LeFort I advancement with market out cephalometric points: Sella (in the middle of sella turcica; Se), A (most dorsal point at the front contour of upper alveolar processus), Porion (upper margin of porus acusticus externus; Po), Orbitale (lower point of orbital margin; Or); and constructed Franfurkt horizontal line (through Po and Or points; FH) and line perpendicular to FH from Po point (Y). SNA angle, vertical (AX) and sagital (AY) position of A point were measured at each cephalogram.

Tab. 1. Time interval between the cephalogram taken immediately after surgery (T2) and during the follow-up (T3) in months.

Patient month 1 33 2 13 3 17 4 13 5 24 Diameter 20 Tab. 2. Measured values of SNA angle and A point position in vertical axis (AX) and horizontal axis (AY) before surgery (T1), immediately surgery (T2), one year after surgery or more (T3) in all five patients.

RESULTS

In all five patients the SNA angle increased of 5.6° on average (from 1.9° to 8.1°) after surgery. In time it decreased back of 4.7° on average. The AY distance increased of 10.7 mm on average (from 4.3 mm to 14.6 mm) after surgery. In the followed time the relapse was of -7.1 mm on average (from -14.5 mm to -1.7 mm). The AX distance changed of -3.4 mm (from -10.6 to 6.1) after surgery. During the follow-up period it changed in the interval from -8.8 to 16.1 with big differences between the patients (Tab. 3, Graph 1 and 2.).

Graph 1. Outcomes of SNA angle measurements in five observed patients before surgery (T1), immediately after surgery (T2), one year or more after surgery (T3).

Graph 2. Outcomes of A-point position measurements in vertical dimension (AX) and horizontal dimension (AY) in the five observed patients before surgery (T1), immediately surgery (T2), one year or more after surgery (T3).

DISCUSSION

The orthognathic surgery is indicated in patients with jaws discrepancy, esthetic handicap and functional problems, who already finished the growth [10]. Maxillary hypoplasia is the most frequent secondary deformity in cleft lip and palate patients. They often have pseudoprogenia and negative overjet. This is based on growth deficiency caused by the defect itself and also on the restriction resulting from the presence of scars after the primary reconstructions of lip, palate and alveolar process. According to the literature, one third to one half of patients born with unilateral cleft lip and palate require not only orthodontic treatment, but also an orthognathic surgery is necessary to achieve satisfactory esthetic and functional results. [11, 12, 13].

Herman Wassmund performed the first osteotomy in line Le Fort I to correct a dentofacial anomaly already in year 1921 [14]. Three decades later Gillies a Millard (1957) carried out this operation in patients with orofacial cleft and the method was popularized in the 1970s by Obwegeser [15, 16]. Later on, this method became a standard treatment procedure of the maxillary hypoplasia in cleft lip and palate. [17, 18, 19]. Since the 1990s the rigid fixation of osteotomy with miniplates gradually replaced the wire fixation greatly improving the postoperative stability.

Orthognathic surgeries in cleft lip and palate patients tend to relapse since the first months after operation [20]. It was proved, that these patients have a higher predisposition to relapse than the patients with maxillary hypoplasia without cleft [20, 21, 22]. It is attributed mainly to the present scar tissue after the previous surgeries, tension in surrounding muscles and mobility of the maxillary segments of the upper jaw [23, 24, 25]. The tendency to relapse increases with severity of maxillary hypoplasia and range of the anterior advancement of the upper jaw.

The orthognathic surgeries in unilateral cleft lip and palate are burdened with significantly bigger relapse in horizontal direction compared with the maxillary distraction [26]. Distraction osteogenesis gradually prolongs the bone and surrounding soft tissues. It distinctly reduces tension in the tissues around the moved segment and decreases the range of relapse [27]. Intraoral and extraoral distractors are available. Both must be implanted and removed during the operation in general anesthesia and stay in situ for at least three months. The extraoral distractor is anchored in temporal bones. This discomfort is compensated by maxillary frontal advancement of up to 14 mm on average [28]. Due to a significant social handicap caused by the extraoral distractor, we nowadays prefer the intraoral one [29]. In case of the intraoral distractor it is possible to achieve the maxillary advancement of 10 to 15 mm as well [29]. For a comparison, the common limit stated in the literature is 6 mm for the immediate maxillary advancement during the orthognathic surgery in the cleft patients [30]. The disadvantages of distractors are a long time of its presence in mouth and a high price of this appliance. Patients with finished growth have higher risk of complications of orthognathic surgery, such as reopening of oronasal or oroantral communication, gingival recession and loosening of preamaxilla in patients with bilateral cleft [31]. The advantages of orthognathic surgery are predictable result, simplicity, and good and almost immediate result, if the treatment plan for both orthodontic and surgical parts was appropriate [32]. No significant difference was found between the distraction and orthognatic surgery in terms of the velopharyngeal closure [26].

Ten studies were reviewed the stability of orthognathic surgery Le Fort I in 584 cleft lip and palate patients at least one year after the operation. The average horizontal regression of a point was 37% and vertical relapse around 65% [11]. Despite big tendency to relapse, the general result was considered sufficient, both in terms of the jaws and the teeth. The final occlusion achieved by the orthognathic surgery was stable in most of the patients.

In all our patients our sample the SNA angle increased, and the A point was shifted anteriorly during the operation. After the one year or more in retention we clearly saw a tendency to relapse, mainly in patients 1 and 4. Considerable range of horizontal relapse can be caused by relatively big shift of the upper jaw during the orthognathic surgery. The final occlusion achieved by the operation was stable and without bigger changes in all five patients. The vertical position of A point doesn`t tend to relapse so much. It can result from different range and orientation of the vertical shift of the upper jaw during the surgery, and from interindividual differences in morphology of the cleft maxilla. Our results are also influenced by a limited number of followed patients. It is necessary to perform a study with more probands.

Some authors suggest using autogenous or allogenous bone material to augment the gap created by the Le Fort I osteotomy to reduce the tendency to relapse. It was proved that this method increases the stability after the surgery especially in horizontal direction, however, there is no significant effect in the vertical direction [33]. This procedure can be also used in the cleft patients. The usage of the bone graft in these patients is very individual, because of the atypical morphology of the cleft maxilla and different extent of the defect.

CONCLUSIONS

The maxilla advancement during the Le Fort I surgery in patients with unilateral total cleft is not stable; the tendency to relapse must be bared in mind. The range of the relapse is individual, probably caused by retraction in places of the original scars, new scar tissue, and tension of surrounding soft tissues. The final occlusion and esthetic improvement are long-term satisfying and stable in these patients according to our experience. To increase the relevancy of this study it is necessary to include more patients to determine the rate and causes of relapse and to evaluate the esthetic results of the treatment.

Corresponding author

MDDr. Václav Placák

Oddělení ústní, čelistní a obličejové chirurgieMasarykova nemocnice o. z.

Sociální péče 3316/12A

400 11 Ústí nad Labem

e-mail: vaclav.placak@kzcr.eu

Zdroje

1. Peterka M, Peterková R, Tvrdek M, Kuderová J, Likovský Z. Significant diferences in the incidence of orofacial clefts in fifty – two Czech districts between 1983–1997. Acta Chir Plast. 2000; 42 : 124–129.

2. Dušková M. Pokroky v sekundární léčbě nemocných s rozštěpem. 1. vydání. Hradec Králové: Olga Čermáková; 2007.

3. Castilla EE, Lopez-Camelo JS, Campana H. Altitude as a risk factor for congenital anomalies. Am J Med Genet. 1999; 86 : 9.

4. Jones MC. Facial clefting. Etiology and developmental pathogenesis. Clin Plast Surg. 1993; 20(4): 599–606.

5. Kriens O. Documentation of cleft lip, alveolus, and palate in In: Bardach J., Morris HL (eds). Multidisciplinary management of cleft lip and palate. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1990.

6. Bardach J, Hughlett LM. Multidisciplinary management of cleft lip and palate. 1. vydání. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1990.

7. Borovec J, Švihlíková Poláčková P, Hofman J, Placák V, Petrová T, Urbanová W, Koťová M.Skeletálně kotvené dlahy typu bollard u pacientů s progenním stavem. Čes Stomatol Prakt zubní lék. 2019; 119 (3): 90–95.

8. Sándor GKB, Genecov D. A comprehensive atlas by cleft lip and palate management. 1. vydání. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015.

9. Yung SY, Ki IU, Jee NK, Dong HS, Hyun GC, Soon HK, Cheol KK, Dong IJ. Bone and soft tissue changes after two-jaw surgery in cleft patients. Arch Plast Surg. 2015; 42(4): 419–423.

10. Kamínek M. a kol. Ortodoncie, 1. vydání. Praha: Galén; 2014.

11. Saltaji H, Major MP, Alfakir H, Al-Saleh MA, Flores-Mir C. Maxillary advancement with conventional orthognathic surgery in patients with cleft lip and palate: is it a stable technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012; 70(12): 2859–2866.

12. Ross RB. Treatment variables affecting facial growth in complete unilateral cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate J. 1987; 24(1): 5–77.

13. Rachmiel A. Treatment of maxillary cleft palate: distraction osteogenesis versus orthognathic surgery-part one: maxillary distraction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65(4): 753–757.

14. Wassmund M. Frakturen und Luxationen des Gesichtsschadels. Leipzig: Meusser; 1927.

15. Gillies HD. Millard DR. The principles and art of plastic surgery. 2. vydání. Boston: Little, Brown & Company; 1957.

16. Obwegeser H. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 4. vydání. 1969; 43(4): 351–365.

17. Kumari P, Roy SK, Roy ID, Kumar P, Datana S, Rahman S. Stability of cleft maxilla in Le Fort I maxillary advancement. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2013; 3 : 139–143.

18. Willmar K. On Le Fort I osteotomy: a fol-low-up study of 106 operated patients with maxillo-facial deformity. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974; 12 : 1–68.

19. Garrison BT, Lapp TH, Bussard DA. The stability of Le Fort I maxillary osteotomies in patients with simultaneous alveolar cleft bone grafts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987; 45 : 761–766.

20. Yingwang JZ, Shen SY, Li B, Sun H, Wang XD. Analysis of three dimensional stability of the hypoplastic maxilla after orthognathic surgery in cleft lip and palate patients. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue. 2016; 25(3): 345–351.

21. Adlam DM, Yau CK, Banks P. A retrospec-tive study of the stability of midface osteo-tomies in cleft lip and palate patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989; 27 : 265–276.

22. Ayliffe PR, Banks P, Martin IC. Stability of the Le Fort I osteotomy in patients with cleft lip and palate. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995; 24 : 201–207.

23. Sadler TW. Langman's Medical Embryology. 10. vydání: Baltomore: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2006.

24. Figueroa AA, Polley JW, Friede H, Ko EW. Long-term skeletal stability after maxillary advancement with distraction osteogenesis using a rigid external distraction device in cleft maxillary deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 114 : 1382–1392.

25. Hirano A, Suzuki H. Factors related to re-lapse after Le Fort I maxillary advancement osteotomy in patients with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2001; 38 : 1–10.

26. Austin SL, Mattick CR, Waterhouse PJ. Distraction osteogenesis versus orthognathic surgery for the treatment of maxillary hypoplasia in cleft lip and palate patients: a systematic review. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2015; 18(2): 96–108.

27. Chua HD, Hägg MB, Cheung LK. Cleft maxillary distraction versus orthognathic surgery – which one is more stable in 5 years? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010; 109(6): 803–814.

28. Painatt JM, Veeraraghavan R, Puthalath U, Peter S, Rao LP, Kuriakose M. Profile changes and stability following distraction osteogenesis with rigid external distraction in adult cleft lip and palate deformities. Contemp Clin Dent. 2017; 8(2): 236–243.

29. Hirjak D, Reyneke JP, Janec J, Beno M, Kupcova I. Long-term results of maxillary distraction osteogenesis in nongrowing cleft: 5-years experience using internal device. Bratisl Lek listy. 2016; 117(12): 685–690.

30. Cheung LK, Chua HD. A meta-analysis of cleft maxillary osteotomy and distraction osteogenesis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 35(1): 14–24.

31. Yamaguchi K, Lonic D, Lo LJ. Complications following orthognathic surgery for patients with cleft lip/palate: A systematic review. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016; 115(4): 269–277.

32. Buchanan EP, Hyman CH. LeFort I osteotomy. Semin Plast Surg. 2013 27(3): 149–154.

33. Martins WD, Ribas Mde O. Horizontal and vertical maxillary osteotomy stability, in cleft lip and palate patients, using allogeneic bone graft. Dental Press J Orthod. 2013; 18(5): 84–90.

Štítky

Chirurgie maxilofaciální Ortodoncie Stomatologie

Článek EditorialČlánek Stomatologie v éře COVID-19

Článek vyšel v časopiseČeská stomatologie / Praktické zubní lékařství

Nejčtenější tento týden

2020 Číslo 2- Horní limit denní dávky vitaminu D: Jaké množství je ještě bezpečné?

- Orální lichen planus v kostce: Jak v praxi na toto multifaktoriální onemocnění s různorodými symptomy?

- Význam ústní sprchy pro čištění mezizubních prostor

- Diagnostika alergie na bílkoviny kravského mléka − aktuální postupy a jejich vypovídací hodnota

- Benzydamin v léčbě zánětů v dutině ústní

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Editorial

- International association of paediatric dentistry (iapd) – 50. Výročí založení

- Early Childhood Caries: IAPD Bangkok Declaration

- Klinické, radiologické a histologické pozorování lidského stálého zubu s neukončeným vývojem ošetřeného neúspěšnou maturogenezí a následným endodontickým ošetřením

- Stabilita ortognátních operací u pacientů s jednostranným celkovým rozštěpem

- Hojení pulpo-parodontální léze po nechirurgickém ošetření

- Vágnost a exaktnost v diagnostice převislého skusu

- Stomatologie v éře COVID-19

- Doporučená ochrana před přenosem virových infekčních onemocnění v době epidemií, nyní zejména SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19

- Česká stomatologie / Praktické zubní lékařství

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Hojení pulpo-parodontální léze po nechirurgickém ošetření

- Stabilita ortognátních operací u pacientů s jednostranným celkovým rozštěpem

- Doporučená ochrana před přenosem virových infekčních onemocnění v době epidemií, nyní zejména SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19

- Vágnost a exaktnost v diagnostice převislého skusu

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání