-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaInfraglenoid fracture of the scapular neck − fact or myth?

Infraglenoidální zlomenina krčku lopatky − skutečnost nebo mýtus?

V roce 1991 popsali Ada a Miller nový typ zlomeniny krčku lopatky. Jednalo se o transverzální zlomeninu těla lopatky probíhající od spodního okraje glenoidu těsně pod spina scapulae do mediálního okraje těla lopatky (jejich typ IIC). Tato zlomenina byla později přejmenována Gossem na “fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine“. Od té doby je tento typ zlomeniny příčinou řady nejasností, zejména v případě tzv. plovoucího ramena. Za zlomeniny krčku lopatky lze považovat pouze ty extraartikulární zlomeniny laterálního úhlu lopatky, které kompletně oddělují glenoid od těla lopatky. Termín „fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine“ tento popis nesplňuje, neboť neodděluje od těla lopatky glenoid, ale velký infraspinátní fragment. Jedná se tedy o příčnou dvou-fragmentovou zlomeninu infraspinátní části těla lopatky. Toto označení by nemělo být dále v literatuře používáno.

Klíčová slova:

zlomeniny lopatky – zlomeniny krčku lopatky – zlomeniny těla lopatky – plovoucí rameno

Authors: J. Bartoníček; M. Tuček

Authors place of work: Department of Orthopaedics, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and Military University Hospital Prague

Published in the journal: Rozhl. Chir., 2019, roč. 98, č. 7, s. 273-276.

Category: Review

Summary

In 1991, Ada and Miller described a new type of scapular neck fracture. It was a transverse fracture of the scapular body passing from the inferior border of the glenoid to the medial border of the scapular body (their type IIC). This fracture was later designated by Goss as a “fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine“. Since then, this type of fracture has been the cause of a number of controversies, mainly concerning the so-called “floating shoulder”. However, scapular neck fractures can be considered to be only those fractures that separate completely the glenoid from the scapular body. Term “fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine“ does not fit into this definition because it does not compromise the junction between the glenoid fossa and the scapular body. Actually, it is a transverse two-part fracture of the infraspinous part of the scapular body. As a result this term should no longer be used in the literature.

Keywords:

scapular fractures – scapular neck fractures – scapular body fractures – floating shoulder

Introduction

Scapular neck fractures are a much-debated issue in the literature [1−10]. Until the beginning of the 1990s, two types of these fractures were primarily recognized, namely those of the surgical and the anatomical necks of the scapula [2−4,7,10]. Some authors specified also a third type, a so-called transspinous fracture of the scapular neck [3−5,10]. In 1991, Ada and Miller [1] described another type that, three years later was designated by Goss [6] as a “fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine.“ Since then, this description has caused much controversy, mainly concerning the so-called “floating shoulder.”

History

In 1991, Ada and Miller [1] published a simple classification scheme where lines IIA, B and C represented fractures of the scapular neck (Fig. 1), but, with neither detailed description, nor explanation in the text. The course of lines drawn on the posterior surface of the scapula suggests that type IIA are fractures of the surgical neck, type II B transspinous scapular neck fractures and type IIC transverse fractures of the scapular body passing from the inferior border of the glenoid just below the scapular spine to the medial border of the scapular body. Fractures of the anatomical neck were not included in this schema.

Fig. 1. Classification of Ada and Miller. II – fractures of scapular neck (Figure adapted from Ada and Miller, [1]). ![Classification of Ada and Miller. II – fractures of

scapular neck (Figure adapted from Ada and Miller, [1]).](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image_pdf/3b8c5715a879d9900719330b52f67c53.png)

In 1994, Goss [6] modified the Ada and Miller “classification” without prior discussion. He excluded transspinous scapular neck fractures, included fractures of the anatomical neck and called the IIC type a “fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine“ (Fig. 2). This term was adopted by other authors without any critical analysis, which caused a confusion that persists in the literature until today [11−15].

Fig. 2. Goss´s classification of scapular neck fractures. A – fracture of anatomical neck, B – fracture of surgical neck, C − fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine (Figure adapted from Goss, Ref. [6]). ![Goss´s classification of scapular neck fractures.

A – fracture of anatomical neck, B – fracture of surgical

neck, C − fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine (Figure

adapted from Goss, Ref. [6]).](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image_pdf/798f47ead2d5643d3def9ad63e683308.png)

Anatomy

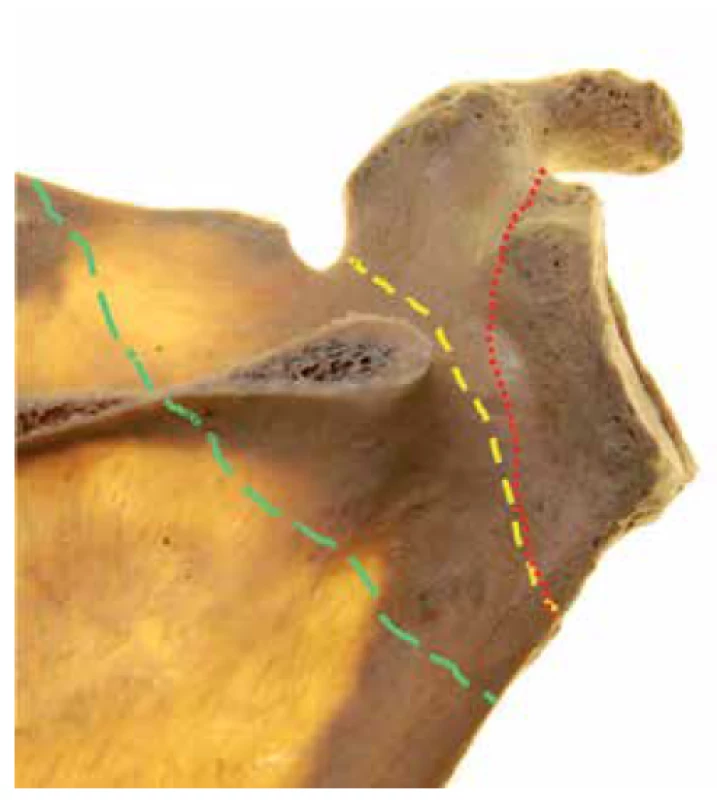

The scapular neck is not an exactly-defined anatomical structure. Anatomical textbooks present the scapular neck as a transitional zone between the scapular body and the glenoid [16]. On the posterior surface of the scapula, this narrowing of the bone mass of the lateral angle can be well seen between the glenoid and the lateral border of the scapular spine as a so-called spinoglenoid notch (Fig. 3). The superior aspect of the neck is formed by the coracoid base, its inferior part is considered to be the subglenoid portion of the lateral border of the scapular body. Based on the course of fracture lines, the region of the scapular neck is further divided into the anatomical and surgical necks (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Fractures of scapular neck. Right scapula, posterior view, with scapular spine resected. Anatomical neck fracture – red, surgical neck fracture – yellow, transspinous neck fracture – green.

Classifications of scapular neck fractures

Scapular neck fractures are defined as extraarticular fractures of the lateral angle of the scapula, which separate the glenoid from the scapular body [3−5,10]. All their types have the common feature of a fracture line running from the lateral border (Fig. 3). Its further course is used to distinguish between the three basic scapular neck fractures, i.e., fractures of the anatomical and surgical necks and transspinous neck fractures. In the spinoglenoid notch the line extends either in the direction of the coracoglenoid notch (anatomical neck fractures) or the scapular notch (surgical neck fractures). Transspinous neck fractures pass from the lateral border, through the middle narrowed portion of the scapular spine, into the supraspinous fossa.

The type IIC of Ada and Miller [1], i.e., the Goss´ [6] “fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine“, does not comply with the definition of a scapular neck fracture as it does not separate the glenoid, but a large infraspinous fragment, from the scapular body. The glenoid remains firmly connected to the superior part of the body, i.e., the spinal column. For this reason, it is a transverse two-part fracture of the infraspinous part of the scapular body. Arguments that it is a scapular neck fracture because the fracture line runs through the subglenoid part of the lateral border of the scapular body that forms the inferior part of the scapular neck, are incorrect. The fracture line does not run through the entire scapular neck.

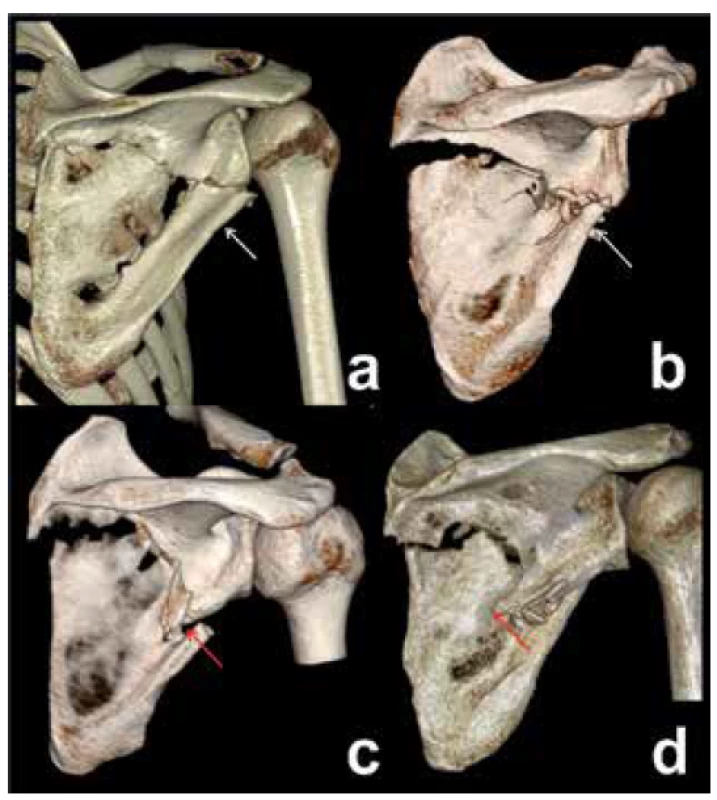

The subglenoid region, or the proximal half of the lateral border, is a typical starting point for a number of fracture lines constituting various types of scapular fractures [17,18]. What is then the difference between the line of a “fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine” and the line of a two-part infraspinous scapular body fracture passing through the lateral border of the scapular body 1 cm to 2 cm more distally (Fig. 4)? In our view there is no difference. In spite of this, e.g., Cole et al. [12], in their 2012 study, designate this fracture pattern (see their Fig. 1c) as a fracture of scapular neck (Fig. 5). Acceptance of this view would imply that almost all infraspinous fractures of the scapular body could be considered as fractures of the scapular neck, although none of them actually affects the junction between the glenoid and the scapular body.

Fig. 4. Types of two-part infraspinous fractures of scapular body, different courses of fracture line. a – immediately below to inferior glenoid rim, b – at the level of the origin of the long head of triceps, c – through the circumflex notch, d – on the border between the superior and inferior halves of the lateral pillar. White arrow – circumflex notch, red arrow – spike of superior fragment. Note the different types of fragment displacement (translation versus angulation with fragment overlap).

Fig. 5. 3D CT reconstruction, posterior view - two-part infraspinous scapular body fracture. The same fracture pattern presented by Cole et al. as “a fracture of scapular neck” (Ref. [12]). ![3D CT reconstruction, posterior view - two-part

infraspinous scapular body fracture. The same fracture

pattern presented by Cole et al. as “a fracture of scapular

neck” (Ref. [12]).](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image_pdf/c19f238add0ae2e76ec36801411e156b.png)

Clinical implications

Two-part infraspinous fractures of the scapular body are presented as fractures of the scapular neck in a number of studies, mainly for two reasons. The first reason is inadequate radiographic diagnosis and, consequently, incorrect classification of a majority of these fractures evaluated solely on radiographs as a surgical neck fracture. Only 3D CT reconstructions can show the true fracture pattern [19]. Another reason is acceptance of Goss´ classification and his deliberate specification of this fracture as a scapular neck fracture.

Bartoníček et al. [18] found, in their series of 375 scapular fractures, that two-part fractures of the insfraspinous part of the scapular body accounted for 24% of all cases and for 47% of the 187 scapular body fractures studied. In addition, almost one third (32%) of two-part infraspinous fractures of the scapular body were associated with a clavicular shaft fracture. Thereby, designation of this pattern as a scapular neck fracture has a number of implications. In epidemiological studies it significantly changes the ratio of the scapular neck and body fractures. For example Tuček et al. [20] recorded in their study 8%, Armitage et al. [17] 22%, Ada and Miller [1] 27% and Zhang 29 % [15] as scapular neck fractures.

The combination of a two-part infraspinous fracture of the scapular body with a fracture of the clavicular shaft is frequently presented in the literature as a “floating shoulder” [8,21,22]. This is another mistake, as it inflates the real number of reported “floating shoulder” cases. [8,21−23].

Ada and Miller [1] recommended operative treatment of scapular neck fractures with a displacement of more than 1 cm, or angulation of more than 40°. However, this recommendation concerned primarily their type IIC type fractures, which are actually scapular body fractures and not scapular neck fractures. Goss [6], followed later by other authors [13,14], adopted these criteria for all types of fractures of scapular neck, without any critical analysis. Thus, these criteria, which were developed solely on the basis of radiographs of scapular body fractures, have been cited in the literature until today, without any verification of their validity [1,6,13,14].

Conclusion

Fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine (IIC type fracture) is a typical example of the controversies surrounding the classification of scapular fractures. Scapular neck fractures can be considered to be only those fractures that completely separate the glenoid from the scapular body. At the same time, it has to be accepted that a scapular neck fracture is a generic term comprising three different types of neck fractures. Their morphological verification requires, in a majority of cases, 3D CT reconstructions. Goss’s ”Fracture of neck inferior to scapula spine“ is not a fracture of the scapular neck, as it does not compromise the junction between the glenoid fossa and the scapular body. As a result this term should no longer be used in the literature.

Supported by IP ZRO MO 1012.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have not conflict of interest in connection with this paper and that the article has not been published in any other journal.

Michal Tuček

Department of Orthopaedics, First Faculty of Medicine,

Charles University and Military University Hospital Prague

U Vojenské nemocnice 1200

169 02, Prague 6

Czech Republic

e-mail: tucekmic@gmail.com

Zdroje

- Ada JR, Miller ME. Scapula fractures. Analysis of 113 cases. Clin Ortop Rel Res. 1991;269 : 174−80.

- Bartoníček J, Cronier P. History of the treatment of scapula fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130 : 83-92. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-0884-y.

- Bartoníček J, Tuček M, Frič V, P Obruba. Fractures of the scapular neck. Diagnosis-classification-treatment. Inter Orthop. 2014;38 : 2163−73. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2434-7.

- Decoulx P, Minet P, Lemerle. Fractures de l´omoplate. Lille Chirurgical 1956;11 : 217−27.

- Gagey O, Curey JP, Mazas F. Les fractures récentes de l´omoplate. A propos de 43 cas. Rev Chir Orthop. 1984;70 : 443−7.

- Goss TP. Fractures of glenoid neck. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3 : 42−52.

- Hardegger F, Simpson LA, Weber BG. The operative treatment of scapula fractures. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66−B:725−31.

- Hersovici D, Fiennes AG, Allgöwer M, et al. The floating shoulder: ipsilateral clavicle and scapular neck fractures. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74−B:362−4.

- Hitzrot JM, Bolling RW. Fractures of the neck of the scapula. Ann Surg. 1916;63 : 215−36.

- Tanton MJ. Fractures du col chirurgical de l´omoplate. J Chir Paris 1913;11 : 701−10.

- Bozkurt M, Can F, Kirdemir V, et al. Conservative treatment of scapula neck fracture: the effect of stability and glenopolar angle on clinical outcome. Injury 2006;36 : 1176−81. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2004.09.013.

- Cole PA, Gauger EM, Herrera DA, et al. Radiographic follow-up of 84 operatively treated scapula neck and body fractures. Injury 2012;43 : 327−33. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.09.029.

- Ebraheim NA, Mechail AO, Padanilum TG, et al. Anatomic considerations for a modified posterior approach to the scapula. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1997;334 : 136−43.

- Jones CB, Cornelius JP, Sietsema DL, et al. Modified Judet approach and minifragment fixation of scapular body and glenoid neck fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2009;23 : 558−64. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181a18216.

- Zhang Y. Scapular fractures. In: Zhang Y. Clinical epidemiology of orthopaedic trauma. Stuttgart, Thieme 2012 : 580−617.

- Frazer JES. The anatomy of the human skeleton. London, Churchill 1946.

- Armitage BM, Wijdicks CA, Tarkin IS, et al. Mapping of scapular fractures with three-dimensional computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91-A:2222-8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00881.

- Bartoníček J, Klika D, Tuček M. Classification of scapular body fractures. Rozhl Chir. 2018;97 : 67−76.

- McAdams TR, Blevins FT, Martin TP, et al. The role of plain films and computed tomography in the evaluation of scapula neck fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2002;16 : 7−11.

- Tuček M, Chochola A, Klika D, et al. Epidemiology of scapular fractures. Acta Orthop Belg. 2017;83 : 8−15.

- DeFranco MJ, Patterson BM. The floating shoulder. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14 : 499−509.

- Lin TL, Li YF, Hsu CJ, et al. Clinical outcome and radiographic change of ipsilateral scapular neck and clavicular shaft fracture: comparison of operation and conservative treatment. J Orthopaedic Surg Res. 2015;10 : 9−16. doi: 10.1186/s13018-014-0141-0.

- Bartoníček J, Klika D, Tuček M. Floating shoulder – myths and reality. J Bone Joint Surg Rew. 2018;6:e5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00198.

Štítky

Chirurgie všeobecná Ortopedie Urgentní medicína

Článek Konference SAGES 2019

Článek vyšel v časopiseRozhledy v chirurgii

Nejčtenější tento týden

2019 Číslo 7- Metamizol jako analgetikum první volby: kdy, pro koho, jak a proč?

- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Hojení análních fisur urychlí čípky a gel

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Klinická výživa v chirurgii a jak dál?

- The most recent recommendations for the surgical treatment of inguinal hernia

- Infraglenoid fracture of the scapular neck − fact or myth?

- Comparison of efficacy of low-volume bowel cleansers prior to colonoscopy: a randomised, prospective, open-label trial

- Mesh fixation in laparoscopic reconstruction of inguinal hernias

- Fistuloclysis as a method of nutritional management in a patient with high output enteroatmospheric fistula – a case report

- Fournier‘s gangrene as Amyand‘s hernia complication

- Splenic abscess as a rare symptom of the extrapulmonary tuberculosis – case report

- Konference SAGES 2019

- Ohlédnutí za mezinárodním kongresem karcinomu žaludku

- Rozhledy v chirurgii

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The most recent recommendations for the surgical treatment of inguinal hernia

- Mesh fixation in laparoscopic reconstruction of inguinal hernias

- Fournier‘s gangrene as Amyand‘s hernia complication

- Fistuloclysis as a method of nutritional management in a patient with high output enteroatmospheric fistula – a case report

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání