-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

The Prevalence of Mental Disorders among the Homeless in Western Countries: Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis

Background:

There are well over a million homeless people in Western Europe and North America, but reliable estimates of the prevalence of major mental disorders among this population are lacking. We undertook a systematic review of surveys of such disorders in homeless people.Methods and Findings:

We searched for surveys of the prevalence of psychotic illness, major depression, alcohol and drug dependence, and personality disorder that were based on interviews of samples of unselected homeless people. We searched bibliographic indexes, scanned reference lists, and corresponded with authors. We explored potential sources of any observed heterogeneity in the estimates by meta-regression analysis, including geographical region, sample size, and diagnostic method. Twenty-nine eligible surveys provided estimates obtained from 5,684 homeless individuals from seven countries. Substantial heterogeneity was observed in prevalence estimates for mental disorders among the studies (all Cochran's χ2 significant at p < 0.001 and all I2 > 85%). The most common mental disorders were alcohol dependence, which ranged from 8.1% to 58.5%, and drug dependence, which ranged from 4.5% to 54.2%. For psychotic illness, the prevalence ranged from 2.8% to 42.3%, with similar findings for major depression. The prevalence of alcohol dependence was found to have increased over recent decades.Conclusions:

Homeless people in Western countries are substantially more likely to have alcohol and drug dependence than the age-matched general population in those countries, and the prevalences of psychotic illnesses and personality disorders are higher. Models of psychiatric and social care that can best meet these mental health needs requires further investigation.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 5(12): e225. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225Summary

Background:

There are well over a million homeless people in Western Europe and North America, but reliable estimates of the prevalence of major mental disorders among this population are lacking. We undertook a systematic review of surveys of such disorders in homeless people.Methods and Findings:

We searched for surveys of the prevalence of psychotic illness, major depression, alcohol and drug dependence, and personality disorder that were based on interviews of samples of unselected homeless people. We searched bibliographic indexes, scanned reference lists, and corresponded with authors. We explored potential sources of any observed heterogeneity in the estimates by meta-regression analysis, including geographical region, sample size, and diagnostic method. Twenty-nine eligible surveys provided estimates obtained from 5,684 homeless individuals from seven countries. Substantial heterogeneity was observed in prevalence estimates for mental disorders among the studies (all Cochran's χ2 significant at p < 0.001 and all I2 > 85%). The most common mental disorders were alcohol dependence, which ranged from 8.1% to 58.5%, and drug dependence, which ranged from 4.5% to 54.2%. For psychotic illness, the prevalence ranged from 2.8% to 42.3%, with similar findings for major depression. The prevalence of alcohol dependence was found to have increased over recent decades.Conclusions:

Homeless people in Western countries are substantially more likely to have alcohol and drug dependence than the age-matched general population in those countries, and the prevalences of psychotic illnesses and personality disorders are higher. Models of psychiatric and social care that can best meet these mental health needs requires further investigation.Introduction

Around 380,000 individuals in the United Kingdom [1] and 740,000 individuals in the United States [2] are reported to be homeless at any given time. Although most live in sheltered accommodation such as emergency hostels, bed and breakfasts, squats, or other temporary accommodation, a recent US report has estimated that 44% are unsheltered, equivalent to over 300,000 people living on the streets [2].

Many studies have reported high prevalences of various health problems among the homeless. Serious physical morbidity, such as tuberculosis and HIV [3], contributes to an increased age-standardised mortality rate of three to four times that in the general population [4,5]. In addition, a number of surveys have found higher rates of serious mental disorders in homeless individuals, but these investigations show at least 10-fold variations in prevalence. Diagnoses of psychosis range from 2% [6] to 31% [7], depression from 4% [8] to 41% [9], and personality disorder from 3% [9] to 71% [10]. It is has been argued that sample selection, case definition, and diagnostic criteria contribute to this heterogeneity [11], although this hypothesis does not appear to have been formally tested. Furthermore, the closure of large psychiatric institutions [12], the shortage of low-cost housing [13], and a lack of community-based supports and services [14] over the past few decades is thought to have contributed to increasing homelessness among people with mental illness, with resulting increased levels of psychiatric morbidity amongst homeless people [8,15]. With the continued reduction in the numbers of inpatient psychiatric beds, the number and proportion of mentally disordered homeless persons is anticipated to increase further [16,17].

Apart from contributing to increased rates of mortality, including from suicide [5,18] and drug abuse [4], the presence of serious mental disorders in the homeless is likely to contribute to increased rates of violent victimization [19], criminality [20–22], and longer periods of homelessness [23]. The provision of good mental health care would therefore reduce psychiatric morbidity and have other public health benefits.

More reliable estimates of the prevalence of serious mental disorders in the homeless should help inform public policy and development of psychiatric services, particularly in urban centres. The most recent review of homeless and mental disorders from 2001 was descriptive and did not attempt a quantitative synthesis of the evidence, or explore the heterogeneity between studies [3]. We report a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of psychiatric surveys of homeless populations in Western countries.

Methods

We searched for surveys that estimated the prevalence of psychotic illness, major depression, personality disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance dependence in homeless people, published between January 1966 and December 2007. We searched computer-based literature indexes (EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO), scanned relevant reference lists, searched relevant journals by hand, and corresponded with authors. For the database search, we used combinations of keywords relating to psychiatric illnesses (e.g., mental*, psych*, depress*, substance/drug*/alcohol* abuse/dependence, personality) and being homeless (e.g., homeless*, roofless, shelter*). Non-English articles were translated. MOOSE guidelines were followed (Text S1).

For inclusion into the systematic review, the studies had to meet the following criteria: (1) A clear definition of homelessness was included; (2) standardized diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders using the International Classification of Diseases: Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders (ICD) or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) were used; (3) psychiatric diagnosis was made by clinical examination or interviews using validated diagnostic instruments; (4) prevalence rates for psychiatric disorders within the previous six months were included, except for personality disorder where lifetime diagnoses were used; (5) study location was in North America, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

Surveys with less than a 50% response rate were excluded, as were surveys on selected populations (for example, a sample of homeless people referred to a psychiatric outpatient clinic or single mothers [24]) or where diagnosis of psychiatric disorders was not obtained by direct interviews (for example, by self report or case note review) or was only reported as 12-mo or lifetime diagnoses [16,25–29]. Studies that selected solely elderly or juvenile people were excluded [30,31]. All the included reports were based on interviews with individuals. We identified one study that interviewed families, but this was excluded as it was based on a selected sample [32].

Information on geographical location; year of interview; definition of homelessness; method of sample selection; sample size; average age; diagnostic instrument; diagnostic criteria, type of interviewer, participation rate; and numbers diagnosed with psychotic illness, major depression, personality disorder, alcohol dependence, and drug dependence was extracted independently from every eligible study. If required, further clarifications were sought by correspondence with authors of relevant studies.

Prevalence estimates were calculated using the variance stabilising double arcsine transformation [33], because of the use of the inverse variance weight in fixed-effects meta-analysis is suboptimal when dealing with binary data with low prevalences. In addition, the transformed prevalences are weighted very slightly towards 50% and studies with zero prevalence can thus be included in the analysis. Confidence intervals (CIs) around these estimates were calculated using the Wilson method [34] since the asymptotic method produces intervals which can extend below zero [35]. Heterogeneity among studies was estimated using Cochran's Q (reported with a χ2-value and p-value) and the I2 statistic, the latter describing the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance [36,37], and presented with a 95% CI [37]. I2, unlike Q, does not inherently depend upon the number of studies considered, with values of 25%, 50%, and 75% taken to indicate low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively. Where heterogeneity was high (I2 > 75%), random effects models were used for summary statistics [36]. In situations with high between-study heterogeneity, the use of random effects models (where the individual study weight is the sum of the weight used in a fixed effects model and the between-study variability) produces study weights that primarily reflect the between-study variation and thus provide close to equal weighting. The use of the arcsine-transformed prevalence estimates consequently had little material difference on the value of the overall random effects estimates, which were themselves found to be notably different (closer to 50%) from the fixed effects estimates in which smaller prevalences have smaller standard errors and thus greater weight. Potential sources of heterogeneity were investigated further by arranging groups of studies according to potentially relevant characteristics and by meta-regression analysis. Factors examined both individually and in multiple variable models were instrument (semistructured instrument versus clinical examination only), interviewer (conducted by mental health clinician or not), period (decade of study: 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s), study size (both a continuous variable and as a categorical variable in increments of n = 50 and n = 100, and also as n < 200 versus n ≥ 200), sex (as appropriate, e.g., male versus female; mixed versus male versus female), geographical region (as appropriate, e.g., mainland Europe versus rest of Western countries), and participation rates (classified into those >85% and those ≤85%). Because of low prevalence and small sample size for some studies, only those factors significant (p < 0.10) individually were entered into a multiple regression model to avoid model instability. The regression coefficients for each study characteristic on individual analysis were provided to enable comparison across diagnoses. All analyses were done in STATA statistical software package, version 10 (Statacorp, 2007) using the commands propcii (to calculate Wilson CIs), metan (for random effects meta-analysis, specifying either two or three variables: double arcsine transformed prevalence and its variance, or double arcsine transformed prevalence and Wilson CIs), and metareg (for meta-regression).

Results

The final sample consisted of 29 studies published between 1979 and 2005 (Table 1) [6–10,38–59]. The studies included a total of 5,684 homeless individuals. Eleven reports reported data on men (n = 1,827) [7,38,40–43,45,47–49,60], 14 included mixed gender samples (n = 3,381) [6,8,39,44,50–54,61], and four investigated women (n = 476) [9,10,40,55]. In the surveys with mixed samples, 82% of the individuals were men (weighted average). The weighted average age of men (reported in eight reports) and women (from four reports) was 41.2 and 33.8 y, respectively. Average age of the mixed samples was 40.1 y (from ten studies). Ten studies were published before 1990 [6–8,10,39,40,42,45,46,49]. Ten reports were from the US (n = 2,019) [6,8,10,38,39,42,49,51,52,55], eight from the UK (n = 1645) [7,44,45,53,56–58,61], six from Germany (n = 624) [9,41,47,48,59,60], two from Australia (n = 473) [40,46], and one each from France (n = 715) [50], The Netherlands (n = 150) [43], and Greece (n = 58) [54].

Tab. 1.

Details of Studies on Prevalence of Mental Disorders in the Homeless Different sampling strategies (random methods, consecutive sampling or total sampling) were used in surveys, apart from two reports that did not provide information on sampling method [59,60]. Of the 5,684 homeless individuals, 952 were selected primarily from shelters for the homeless, 583 from hostels for the homeless, and the rest from a mixture of settings including day centres, soup kitchens, missions, streets, and shelters. Eight studies reported response rate of above 90% [6–8,38,45,49,53,55], the others were mostly above 70%. Three reports did not provide response rates [54,56,61], a further one did not cite the response rate for part of the sample [40], and five surveys reported response rates between 60% and 70% [42–44,47,52].

In six surveys, diagnosis of psychotic illness, major depression, personality disorder, alcohol dependence, and drug dependence was made by clinical examination without the use of diagnostic instruments (n = 600) [7,8,10,51,54]. Validated semistructured diagnostic instruments used included: Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (n = 1,455) [6,9,38,39,52,55]; Clinical Interview Schedule, Revised (CIS-R) (n = 1,090) [57,58]; Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (SCID) (n = 1,081) [40,41,47,56,59]; Present State Examination (PSE) (n = 394) [44,45,49,53], and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (n = 724) [43,48,50]. Three other studies used clinical semistructured interviews [48,60,61].

Psychotic Illness

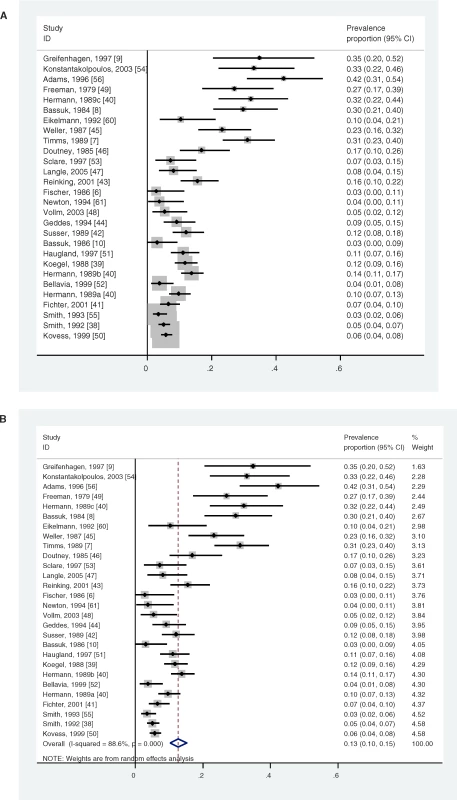

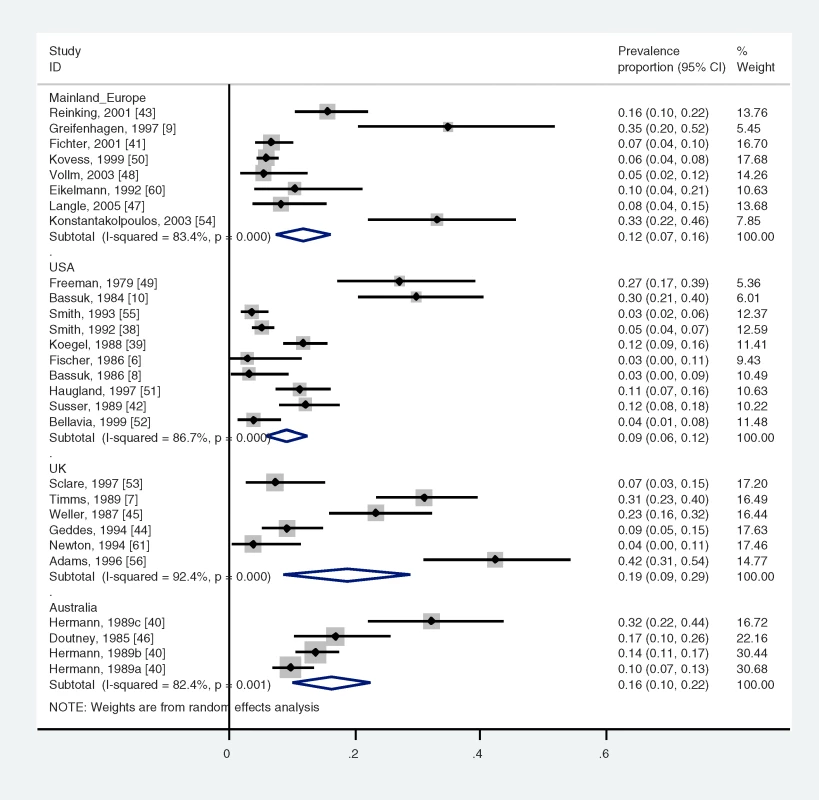

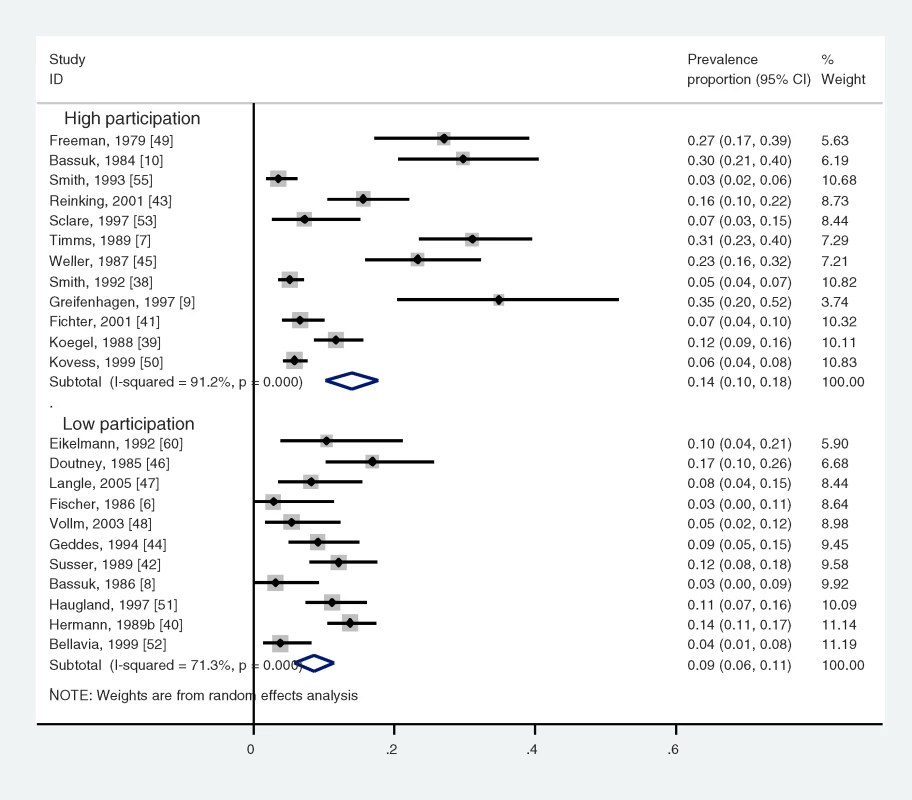

Psychotic illness was reported in 28 surveys with a random effects pooled prevalence of 12.7% (95% CI 10.2%–15.2%) [6–10,38–56,60,61]. Estimates ranged from 2.8% to 42.3% with substantial heterogeneity among the estimates (χ2 = 237.7, p < 0.001, I2 = 88.6%, 95% CI 84.8%–91.5%). Higher prevalences were found in smaller studies (Figure 1). We further explored study region, grouping studies according to whether they were based in mainland Europe, UK, US, or Australasia (Figure 2). In individual variable meta-regression analyses, surveys in which the interviewer was a mental health clinician (versus a lay interviewer) had higher prevalences of psychosis (β = 0.08, standard error [se(β)] = 0.04, p = 0.042), where the participation rates were lower (<85%) had lower prevalences (β = −0.06, se[β] = 0.03, p = 0.071) (Figure 3), and where the study size was 200 or more participants (versus fewer than 200) had lower prevalences (β = −0.08, se[β] = 0.04, p = 0.055) (Table 2). In a meta-regression model including these three characteristics, only the participation rate remained significant: lower participation rates were associated with lower prevalences (β = −0.08, se[β] = 0.03, p = 0.015).

Fig. 1. Prevalence of Psychosis in Homeless Persons

(A) Studies are ordered by increasing study weight in a fixed effects model without calculation of an overall estimate. Fig. 2. Prevalence of Psychosis in Homeless Persons by Country Group

Fig. 3. Prevalence of Psychosis in Homeless Persons by Participation Rate

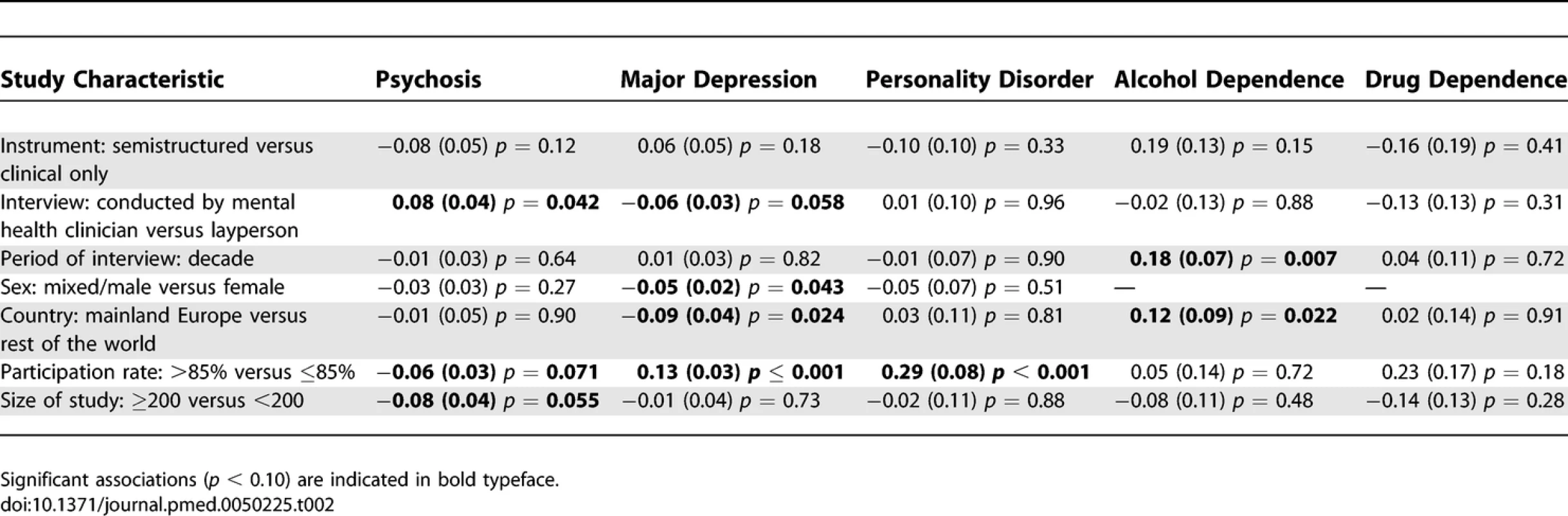

Tab. 2.

Results of Individual Variable Meta-Regression Models for Each Diagnosis Showing Values of β, se(β), and the Significance of β for Each Study Characteristic Major Depression

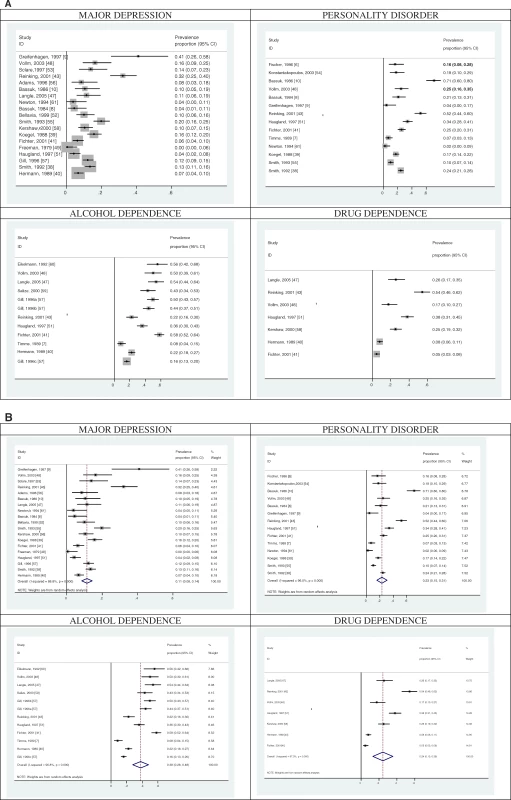

We identified 19 surveys that reported major depression with a random effects pooled prevalence estimate of 11.4% (95% CI 8.4%–14.4%) (Figure 4) [8–10,38–41,43,47–49,51–53,55–58,61]. The prevalence estimates ranged from 0.0% to 40.9% and there was substantial heterogeneity among those estimates (χ2 = 160.6, p < 0.001, I2 = 88.8%, 95% CI 84.0%–92.2%). Four factors were associated with this heterogeneity on meta-regression: the interview being conducted by a mental health clinician, where there were lower prevalences (β = −0.06, se[β] = 0.04, p = 0.058); the study being conducted in mainland Europe compared with the rest of the world (β = −0.09, se[β] = 0.04, p = 0.024); sex (coded as female, male, mixed), with men and mixed samples having progressively lower prevalences than women (β = −0.05, se[β] = 0.02, p = 0.043); and participation rate, with lower participation rates being associated with higher prevalences (β = 0.13, se[β] = 0.03, p < 0.001) (Table 2). In a meta-regression model including these four characteristics, only the participation rate remained significant: lower participation rates were associated with higher prevalences (β = 0.11, se[β] = 0.03, p = 0.002).

Fig. 4. Prevalence of Major Depression, Personality Disorder, Alcohol Dependence, and Drug Dependence in Homeless People

(A) Studies are ordered by increasing study weight in a fixed effects model without calculation of an overall estimate. Personality Disorder

We identified 14 surveys that reported personality disorder diagnoses in 2,413 homeless persons (Figure 4) [6–10,38,39,41,48,51,54,55,61]. The prevalence estimates ranged from 2.2% to 71.0%. The random effects pooled prevalence estimate was 23.1% (95% CI 15.5%–30.8%) (χ2 = 327.5, p < 0.001, I2 = 96.0%, 95% CI 94.6%–97.1%), with only one of the sample characteristics being significantly associated with this substantial heterogeneity on individual variable analysis: lower participation rates were associated with higher prevalences (β = 0.29, se[β] = 0.08, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

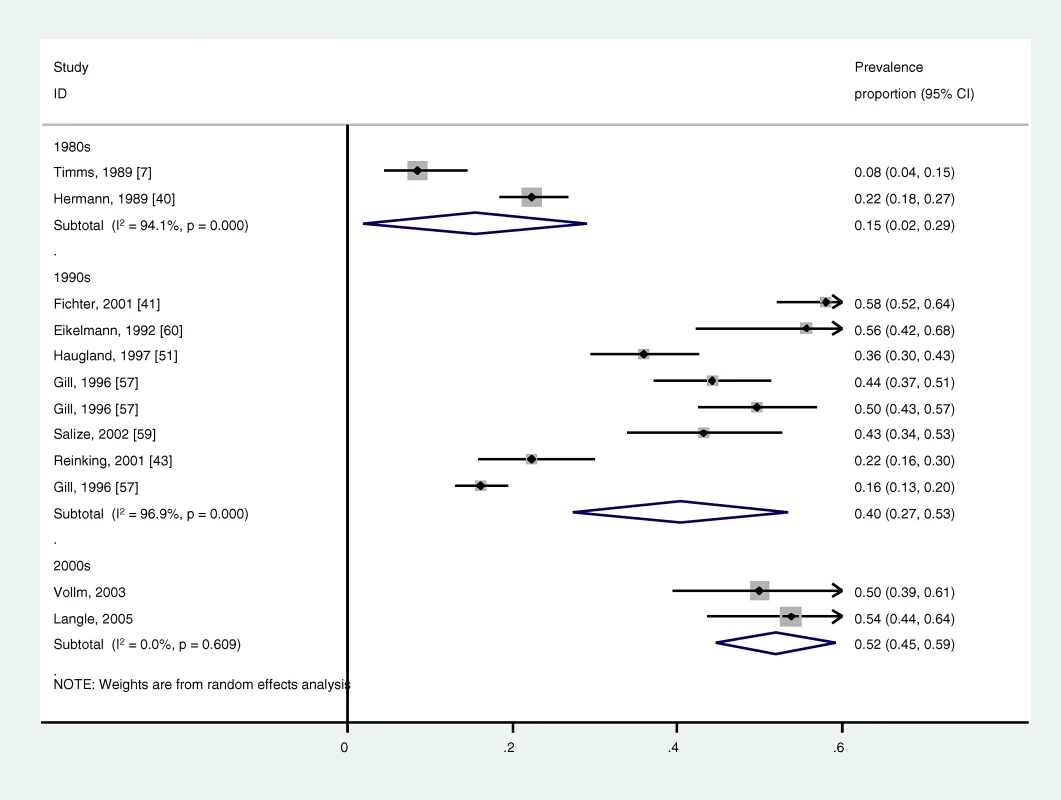

Alcohol Dependence

We identified ten surveys that reported alcohol dependence in 1,791 homeless men (Figure 4) [7,40,41,43,47,48,51,57,59,60]. The prevalence estimates ranged from 8.5% to 58.1%. The random effects pooled prevalence estimate was 37.9% (95% CI 27.8%–48.0%) (χ2 = 347.2, p < 0.001, I2 = 96.8%, 95% CI 95.7%–97.7%). Two factors were associated with this heterogeneity on individual but not multiple variable analysis. First, the more recent the study (as analysed by decade), the higher the prevalence of alcohol dependence (β = 0.18, se[β] = 0.07, p = 0.007, Figure 5). Second, surveys conducted in mainland Europe had higher prevalences of alcohol dependence (β = 0.21, se[β] = 0.09, p = 0.022) (Table 2). We did not find any investigations of alcohol dependence in homeless women.

Fig. 5. Prevalence of Alcohol Dependence in Homeless Persons by Decade

Drug Dependence

We identified seven surveys in men that reported drug dependence (Figure 4) [40,41,43,47,48,51,58]. The prevalence estimates ranged from 4.7% to 54.2%. Random effects pooled prevalence estimate was 24.4% (95% CI 13.2%–35.6%) (χ2 = 221.1, p < 0.001, I2 = 97.3%, 95% CI 95.9%–98.2%), with none of the sample characteristics being significantly associated with this heterogeneity on individual variable analysis (Table 2). We found one report on drug dependence in homeless women (n = 33) with a prevalence of 24.2% [58].

Conclusion

This systematic review of serious mental disorders in homeless persons identified 29 surveys including 5,684 individuals. There are three main findings. First, the most common mental disorders appeared to be alcohol and drug dependence, with random effects pooled prevalence estimates of 37.9% (95% CI 27.8%–48.0%) and 24.4% (95% CI 13.2%–35.6%), respectively. Second, the prevalence estimates for psychosis were at least as high as those for depression, a finding in marked contrast from community estimates of these conditions [62,63], and in other at-risk groups such as prisoners [64] and refugees [65], in whom depression is more common. Third, although high prevalences were reported for serious mental disorders, their substantial heterogeneity suggests that service planning should not rely on our summary estimates but commission local surveys of morbidity to quantify mental health needs.

The substantial heterogeneity between the studies included in the review was not unexpected. Some of the variations between studies could be not explained by crude study characteristics (such as sex, study size, or geographic region), and this suggests that local factors such as provision of mental health and social services are likely to be important [66]. However, certain other study characteristics were associated with heterogeneity on meta-regression. These included, first, lower participation in surveys were associated with lower prevalences of psychosis. Second, interviewers with clinical training were more likely to reporting lower prevalences of depression. Third, a higher prevalence of alcohol dependence was found in studies in more recent decades, possibly reflecting the increasing relative affordability of alcohol [67,68].

The prevalence of psychosis ranged between 3% and 42%, which is substantially higher than community estimates, which typically report 1%–2% when individuals are surveyed using diagnostic instruments [69], and up to 0.8% when only schizophrenia is reported [70]. We found no increase in the prevalence of psychosis by study period (in decades), in contrast with the views of some commentators [15,16]. The finding on meta-regression that the proportion of the individuals who participated was significantly associated with these prevalences suggests that researchers in the field need to interpret their findings in light of response rates. Reasons for nonparticipation in research may be related to severe mental illness, and investigators should consider gathering information from other sources to estimate the degree of underestimation or attempt to reinterview those who did not participate initially.

Although the proportionate excess for psychosis was greater than for the other mental disorders, this review found that the main mental health problem for homeless persons is alcohol dependence, which ranged from 8% to 58%. On average, this is many orders of magnitude higher in men and even higher in women compared with community surveys [62,63]. The range for drug dependence were 5%–54%, a proportionate excess higher in women than men compared with community surveys [62,63]. The increased prevalence for drug dependence in both sexes may contribute to the reported increased crime rates in the homeless [20,21,22], as substance abuse and dependence is an important risk factor, either alone [71] or comorbid with psychosis [21].

The prevalence of depression in this review, with a pooled prevalence estimate of 11.4% (95% CI 8.4%–14.4%), range at 0% to 41%, was lower than expected. Many estimates included in the review were similar to community estimates of depression in women (which range from 7% to 11% for 1-y estimates), and only slightly higher than general population rates for men [62,72]. While levels of comorbidity of depression are likely to be underreported in homeless persons with psychosis or drug dependence, these estimates suggest that the reported high rates of suicide in homeless people [5,18] may not be mediated through depressive illness, and that other risk factors, such alcohol dependence, may be more relevant [73]. The finding that clinically trained interviewers were associated with lower prevalence estimates is consistent with a systematic review of major depressive disorder in prisoners [64], and suggests that studies of the diagnostic validity of depression using different types of interviewer should be researched. In terms of the prevalence of personality disorder in the homeless, we found that the estimates varied widely (range 2.2%–71.0%), and all but one reported rates higher than the 4.4% found in a recent community survey [74]. The presence of personality disorder is associated with poorer outcomes for treatment of depression [75] and increased risk of deliberate self-harm [76].

One of the findings of this review is that future research in homeless populations should provide clear definitions of the sample interviewed and breakdowns by type of homelessness category (whether it be roofless or temporary accommodation). Although we identified and excluded from the review one study from a non-Western population (South Korea) [77], it highlighted the need for research in non-Western countries. Longitudinal studies of cohorts of the mentally ill would help clarify the risk for, temporal sequence of, and pathways into homelessness, and identify risk factors and those associated with desistence for homelessness in such populations.

A number of implications for health services for the homeless arise from this review. Integrating treatment for mental illness, substance dependence, and housing interventions should be considered for many homeless persons [78,79], and hospital admission may be required for treatment for a number with psychotic illness. Local surveys are needed to inform service needs. However, traditional models of service delivery in Western countries, which focus on those with severe mental illness, may not meet the mental health needs of most homeless people who suffer from substance dependence and personality disorder. Even when mentally ill homeless persons receive adequate mental health services, a range of unmet welfare and housing needs may remain, implying that normal community mental health service provision is usually insufficient [80]. With many millions of individuals being homeless in Western countries, current mental health provision may need review, and models of psychiatric and social care that can best meet the burden of mental illness will need further investigation.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Crisis

2003

How many and how much: Single homelessness and the question of numbers and cost

London

Crisis UK

2. Homelessness Research Institute

2007

Homelessness counts

Washington (D.C)

National Alliance to End Homelessness

3. MartensW

2001

A review of physical and mental health in homeless persons.

Public Health Rev

29

13

33

4. BarrowSMHermanDBCordovaPStrueningEL

1999

Mortality among homeless shelter residents in New York City.

Am J Public Health

89

529

534

5. BabidgeNCBuhrichNButlerT

2001

Mortality among homeless people with schizophrenia in Sydney, Australia: A ten year follow-up.

Acta Psychiatr Scand

103

105

110

6. FischerPJShapiroSBreakeyWRAnthonyJCKramerM

1986

Mental health and social characteristics of the homeless: A survey of mission users.

Am J Public Health

76

519

524

7. TimmsPWFryAH

1989

Homelessness and mental illness.

Health Trends

21

70

71

8. BassukELRubinLLauriatA

1984

Is homelessness a mental health problem.

Am J Psychiatry

141

1546

1550

9. GreifenhagenAFichterM

1997

Mental illness in homeless women: An epidemiological study in Munich, Germany.

Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci

247

162

172

10. BassukELRubinLLauriatAS

1986

Characteristics of sheltered homeless families.

Am J Public Health

76

1097

1101

11. FischerPJ

1989

Estimating the prevalence of alcohol, drug and mental health problems in the contemporary homeless population: a review of the literature.

Contemp Drug Probl

16

333

390

12. ApplebyLDesaiPN

1985

Documenting the relationship between homelessness and psychiatric hospitalization.

Hosp Comm Psychiatry

37

732

737

13. WrightJLamJ

1987

Homelessness and the low-income housing supply.

Soc Policy

17

48

53

14. KushelMVittinghoffEHaasJ

2001

Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons.

JAMA

285

200

206

15. LambHR

1984

Deinstitutionalisation and the homeless mentally ill.

Hosp Comm Psychiatry

35

899

907

16. NorthCSEyrichKMPollioDESpitznagelEL

2004

Are rates of psychiatric disorders in the homeless population changing.

Am J Public Health

94

103

108

17. TeesonM

1990

Prevalence of schizophrenia in a refuge for homeless men: A five year follow-up.

Psychiatric Bull

14

597

600

18. PrigersonHGDesaiRALiu-MaresWRosenheckRA

2003

Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in homeless mentally ill persons: Age-specific risks of substance abuse.

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol

38

213

219

19. WalshEMoranPScottCMcKenzieKBurnsT

2003

Prevalence of violent victimisation in severe mental illness.

Br J Psychiatry

183

233

238

20. GelbergLLinnLSLeakeBD

1988

Mental health, alcohol and drug use, and criminal history among homeless adults.

Am J Psychiatry

145

191

196

21. BrennanPMednickSHodginsS

2000

Major mental disorders and criminal violence in a Danish birth cohort.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

57

494

500

22. FazelSGrannM

2006

The population impact of severe mental illness on violent crime.

Am J Psychiatry

163

1397

1403

23. MorseGShieldsNMHannekeCRMcCallGJCalsynRJ

1986

St. Louis's homeless: Mental health needs, services, and policy implications.

Psychosocial Rehab J

9

39

50

24. BassukELBucknerJCPerloffJNBassukSS

1998

Prevalence of mental health and substance use disorders among homeless and low-income housed mothers.

Am J Psychiatry

155

1561

1564

25. TeessonSHodderTBuhrichN

2000

Substance use disorders among homeless people in inner Sydney.

Soc Psychiat Psychiatr Epidemiol

35

451

456

26. TeessonMHodderTBuhrichN

2004

Psychiatric disorders in homeless men and women in inner Sydney.

Aust N Z J Psychiatry

38

162

168

27. VirgonaABuhrichNTeessonM

1993

Prevalence of schizophrenia among women in refuges for the homeless.

Aust N Z J Psychiatry

27

405

410

28. VazquezCMunozMSanzJ

1997

Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R mental disorders among the homeless in Madrid: A European study using the CIDI.

Acta Psychiatr Scand

95

523

530

29. LovisiGMannACoutinhoEMorgadoA

2004

Mental illness in an adult sample admitted to public hostels in the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan area, Brazil.

Soc Psychiat Psychiatr Epidemiol

38

493

498

30. PriestRG

1976

The homeless person and the psychiatric services: an Edinburgh survey.

Br J Psychiatry

128

128

136

31. ReillyJJHerrmanHEClarkeDMNeilCCMcNamaraCL

1994

Psychiatric disorder in and service use by young homeless people.

Med J Aust

161

429

432

32. VostanisPGrattanECumellaS

1998

Mental health problems of homeless children and families: longitudinal study.

BMJ

316

899

902

33. FreemanMTukeyJ

1950

Transformations related to the angular and the square root.

Ann Math Stats

4

607

611

34. WilsonE

1927

Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference.

J Am Stat Assoc

22

209

212

35. NewcombeR

1998

Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods.

Stats Med

17

857

872

36. HigginsJThompsonSDeeksJAltmanD

2003

Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses.

BMJ

327

557

560

37. HigginsJThompsonS

2002

Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis.

Stats Med

21

1539

1558

38. SmithEMNorthCSSpitznagelEL

1992

A systematic study of mental illness, substance abuse, and treatment in 600 homeless men.

Ann Clin Psychiatry

4

111

120

39. KoegelPBurnamMAFarrRK

1988

The prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among homeless individuals in the inner city of Los Angeles.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

45

1085

1092

40. HerrmanHMcGorryPBennettPVan RielRSinghB

1989

Prevalence of severe mental disorders in disaffiliated and homeless people in inner Melbourne.

Am J Psychiatry

146

1179

1184

41. FichterMMQuadfliegN

2001

Prevalence of mental illness in homeless men in Munich, Germany: Results from a representative sample.

Acta Psychiatr Scand

103

94

104

42. SusserEStrueningELConoverS

1989

Psychiatric problems in homeless men. Lifetime psychosis, substance use, and current distress in new arrivals at New York City shelters.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

46

845

850

43. ReinkingDPWolfJRKroonH

2001

Hoge prevalentie van psychische stoornissen en verslavingsproblemen bij daklozen in de stad Utrecht [High prevalence of mental disorders and addiction problems among the homeless in Utrecht].

Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd

145

1161

1166

44. GeddesJNewtonRYoungGBaileySFreemanC

1994

Comparison of prevalence of schizophrenia among residents of hostels for homeless people in 1966 and 1992.

BMJ

308

816

819

45. WellerBGWellerMPCokerEMahomedS

1987

Crisis at Christmas 1986.

Lancet

1

553

554

46. DoutneyCPBuhrichNVirgonaACohenADanielsP

1985

The prevalence of schizophrenia in a refuge for homeless men.

Aust N Z J Psychiatry

19

233

238

47. LangleGEgerterBAlbrechtFPetraschMBuchkremerG

2005

Prevalence of mental illness among homeless men in the community - Approach to a full census in a southern German university town.

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol

40

382

390

48. VollmBBeckerHKunstmannW

2004

Psychiatrische Morbidität bei allein stehenden wohnungslosen Männern [Psychiatric morbidity in homeless single men].

Psychiatr Prax

31

236

240

49. FreemanSJFormoAAlampurAGSommersAF

1979

Psychiatric disorder in a skid-row mission population.

Compr Psychiatry

20

454

462

50. KovessVMangin LazarusC

1999

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders and use of care by homeless people in Paris.

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol

34

580

587

51. HauglandGSiegelCHopperKAlexanderMJ

1997

Mental illness among homeless individuals in a suburban county.

Psychiatr Serv

48

504

509

52. BellaviaCWToroPA

1999

Mental disorder among homeless and poor people: a comparison of assessment methods.

Community Ment Health J

35

57

67

53. SclarePD

1997

Psychiatric disorder among the homeless in Aberdeen.

Scot Med J

42

173

177

54. KonstantakopoulosGKakoulasIValmaVStamatogiannopoulouEGiotakosO

2003

Mental disorders and dual diagnosis in a sample of homeless people in Athens.

Annals Gen Hosp Psychiatry

2

Suppl 1

S113

55. SmithEMNorthCSSpitznagelEL

1993

Alcohol, drugs, and psychiatric comorbidity among homeless women: an epidemiologic study.

J Clin Psychiatry

54

82

87

56. AdamsCEPantelisCDukePJBarnesTR

1996

Psychopathology, social and cognitive functioning in a hostel for homeless women.

Br J Psychiatry

168

82

86

57. GillBMeltzerHHindsKPetticrewM

1996

Psychiatric morbidity among homeless people

London

HMSO

58. KershawASingletonNMeltzerH

2000

Substance misuse and mental disorder among homeless people in Glasgow

London

ONS

59. SalizeHJDillmann-LangeCSternGKentner-FiguraBStammK

2002

Alcoholism and somatic comorbidity among homeless people in Mannheim, Germany.

Addiction

97

1593

1600

60. EikelmannBInhesterMLRekerT

1992

Psychische Störungen bei nicht-sesshaften Männern. Defizite in der psychiatrischen Versorgung.

Sozialpsychiatrische Informationen

2

29

32

61. NewtonJRGeddesJRBaileySFreemanCPMcAleavyA

1994

Mental health problems of the Edinburgh 'roofless'.

Br J Psychiatry

537

540

62. KesslerRMcGonagleKZhaoS

1994

Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

51

8

19

63. KesslerRCChiuWTDemlerOWaltersEE

2005

Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

62

617

627

64. FazelSDaneshJ

2002

Serious mental disorder in 23 000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys.

Lancet

359

545

550

65. FazelMWheelerJDaneshJ

2005

Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: A systematic review.

Lancet

365

1309

1314

66. TischlerVCumellaSBellerbyTVostanisP

2000

Service innovations: A mental health service for homeless children and families.

Psychiatr Bull

24

339

341

67. FarrellSManningWGFinchMD

2003

Alcohol dependence and the price of alcoholic beverages.

J Health Econ

22

117

147

68. RoomR

2005

Alcohol and public health.

Lancet

365

519

69. RobinsRReigerD

1991

Psychiatric disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study

New York

The Free Press

70. SahaSChantDWelhamJMcGrathJ

2005

A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia.

PLoS Medicine

2

e141

doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141

71. GrannMFazelS

2004

Substance misuse and violent crime: Swedish population study.

BMJ

328

1233

1234

72. KesslerRCBerglundPDemlerOJinRKoretzD

2003

The Epidemiology of Major Depressive Disorder: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R).

JAMA

289

3095

3105

73. CavanaghJCarsonASharpeMLawrieS

2003

Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review.

Psychol Med

33

395

405

74. CoidJYangMTyrerPRobertsAUllrichS

2006

Prevalence and correlates of personality disorders in Great Britain.

Br J Psychiatry

188

423

431

75. Newton-HowesGTyrerPJohnsonT

2006

Personality disorder and the outcome of depression: meta-analysis of published studies.

Br J Psychiatry

188

13

20

76. HawtonKHoustonKHawCTownsendEHarrissL

2003

Comorbidity of axis I and axis II disorders in patients who attempted suicide.

Am J Psychiatry

160

1494

1500

77. HanOSLeeHBAhnJHParkJIChoMJ

2003

Lifetime and current prevalence of mental disorders among homeless men in Korea.

J Nerv Ment Dis

4

272

275

78. DrakeRYovetichNBeboutRHarrisMMcHugoG

1997

Integrated treatment for dually diagnosed homeless adults.

J Nerv Ment Dis

185

298

305

79. GoldfingerSMSchuttRKTolomiczenkoGSSeidmanLPenkWE

1999

housing placement and subsequent days homeless among formerly homeless adults with mental illness.

Psychiatr Serv

50

674

679

80. HerrmanHEvertHHarveyCGurejeOPinzoneT

2004

Disability and service use among homeless people living with psychotic disorders.

Aust N Z J Psychiatry

38

965

974

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2008 Číslo 12- Není statin jako statin aneb praktický přehled rozdílů jednotlivých molekul

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

- Moje zkušenosti s Magnosolvem podávaným pacientům jako profylaxe migrény a u pacientů s diagnostikovanou spazmofilní tetanií i při normomagnezémii - MUDr. Dana Pecharová, neurolog

- Biomarker NT-proBNP má v praxi široké využití. Usnadněte si jeho vyšetření POCT analyzátorem Afias 1

- Antikoagulační léčba u pacientů před operačními výkony

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- The Prevalence of Mental Disorders among the Homeless in Western Countries: Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis

- Health and Human Rights Concerns of Drug Users in Detention in Guangxi Province, China

- African AIDS Vaccine Programme for a Coordinated and Collaborative Vaccine Development Effort on the Continent

- Mental Disorders among Homeless People in Western Countries

- The Disconnect between China's Public Health and Public Security Responses to Injection Drug Use, and the Consequences for Human Rights

- What Is the Future for Global Case Management Guidelines for Common Childhood Diseases?

- The Dirty War Index: A Public Health and Human Rights Tool for Examining and Monitoring Armed Conflict Outcomes

- Poverty and Cataract—A Deeper Look at a Complex Issue

- The Dirty War Index: Statistical Issues, Feasibility, and Interpretation

- A New Tool for Measuring the Brutality of War

- Accessing Maternal Health Services in Eastern Burma

- “Efforts to Reprioritise the Agenda” in China: British American Tobacco's Efforts to Influence Public Policy on Secondhand Smoke in China

- Homelessness Is Not Just a Housing Problem

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Homelessness Is Not Just a Housing Problem

- The Dirty War Index: A Public Health and Human Rights Tool for Examining and Monitoring Armed Conflict Outcomes

- Accessing Maternal Health Services in Eastern Burma

- Poverty and Cataract—A Deeper Look at a Complex Issue

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání