-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaIdentification of Four Mouse Diabetes Candidate Genes Altering β-Cell Proliferation

Complex genetic determinants contribute to an inherent susceptibility of type 2 diabetes, characterized by insulin resistance, a dysfunction and loss of insulin-producing beta-cells. We compared the islet expression profile and the genome of two obese mouse strains that react differently when receiving a caloric enriched diet. One mouse (B6-ob/ob) is able to compensate by increasing the beta-cell mass, whereas the other (NZO) develops hyperglycemia due to beta-cells loss. Focusing on differentially expressed genes that are located in susceptibility locus for diabetes and obesity on chromosome 1 we found 6 genes to be only expressed in islets of the diabetes-resistant mouse and one to be exclusively present in islets of the diabetes-prone mouse. Among these, the overexpression of 3 genes (Lefty1, Apoa2, and Pcp4l1) increased and that of Ifi202b decreased the division of primary islet cells. In summary, our data provide new insights into genes inducing or inhibiting islet size and thereby participate in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005506

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005506Summary

Complex genetic determinants contribute to an inherent susceptibility of type 2 diabetes, characterized by insulin resistance, a dysfunction and loss of insulin-producing beta-cells. We compared the islet expression profile and the genome of two obese mouse strains that react differently when receiving a caloric enriched diet. One mouse (B6-ob/ob) is able to compensate by increasing the beta-cell mass, whereas the other (NZO) develops hyperglycemia due to beta-cells loss. Focusing on differentially expressed genes that are located in susceptibility locus for diabetes and obesity on chromosome 1 we found 6 genes to be only expressed in islets of the diabetes-resistant mouse and one to be exclusively present in islets of the diabetes-prone mouse. Among these, the overexpression of 3 genes (Lefty1, Apoa2, and Pcp4l1) increased and that of Ifi202b decreased the division of primary islet cells. In summary, our data provide new insights into genes inducing or inhibiting islet size and thereby participate in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes.

Introduction

The hallmark of type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a relative hypoinsulinemia which is unable to compensate insulin resistance and is a result of beta-cell failure [1]. In mouse models of obesity, differences in beta-cell adaptation to increased insulin demand are due to an underlying genetic background causing either diabetes susceptibility or resistance. B6-ob/ob mice lacking leptin on the C57BL/6 background become obese and insulin resistant but do not develop hyperglycemia because of massive beta-cell proliferation and high serum insulin levels. In contrast, the C57BLKS mice carrying the ob/ob mutation do not adapt to increased insulin requirements and die of severe hyperglycemia [2,3].

Here we compared the genetics and pathomechanisms of the diabetes resistant B6-ob/ob mouse with the diabetes-prone New Zealand Obese (NZO) mouse that represents an excellent model for polygenic obesity and type 2 diabetes and resembles the human disease. By positional cloning we have previously identified the adipogenic and diabetogenic genes Tbc1d1 [4], Ifi202b [5], and Zfp69 [6] of which the human orthologues also appear to be involved in the progression of human obesity and T2D [6–8].

Interestingly, restriction of carbohydrates protects diabetes-prone mice (NZO, db/db on C57BLKS background) from hyperglycemia, but re-exposure to carbohydrates causes rapid development of hyperglycemia and beta-cell apoptosis within a few days [9–11]. We have recently developed a dietary intervention which allowed a very fast and synchronized beta-cell failure in NZO-mice. By feeding a carbohydrate-free diet for about 15 weeks and subsequent treatment with carbohydrates we were able to follow early pathogenic alterations in the islets in a time course of 16 and 32 days. We discovered a rapid induction of hyperglycemia, a decreased AKT signaling and subsequent induction of apoptosis in the islets of Langerhans from NZO mice [10,12].

In the present study we used an integrated approach to identify novel disease genes. We compared the transcriptome profile of islets from NZO and B6-ob/ob mice that were treated with carbohydrates only for two days subsequent to the carbohydrate-free feeding and combined the expression pattern with a MetaCore enrichment pathway analysis and with QTL identified in the F2(NZOxB6) [13]. Several transcripts of cell-cycle regulation are likely to be associated with the pathogenesis of diabetes because their expression in islets of Langerhans is non-responsive to an in-vivo glucose challenge in the diabetes-sensitive strain. Mapping of differentially expressed genes to the major diabetes QTL Nob3 on chromosome 1 identified 15 genes of which 7 exhibited an exclusive expression in one strain. Direct evidence was obtained for four genes of which three appear to be involved in the compensatory capacity of B6-ob/ob islets: Lefty1, Pcp4l1, and Apoa2 exclusively expressed in B6-ob/ob islets increased proliferation. In contrast, Ifi202b which is not expressed in B6 suppressed proliferation when overexpressed in primary islet cells.

Results

Induction of proliferation in islets of diabetes-resistant B6-ob/ob mice

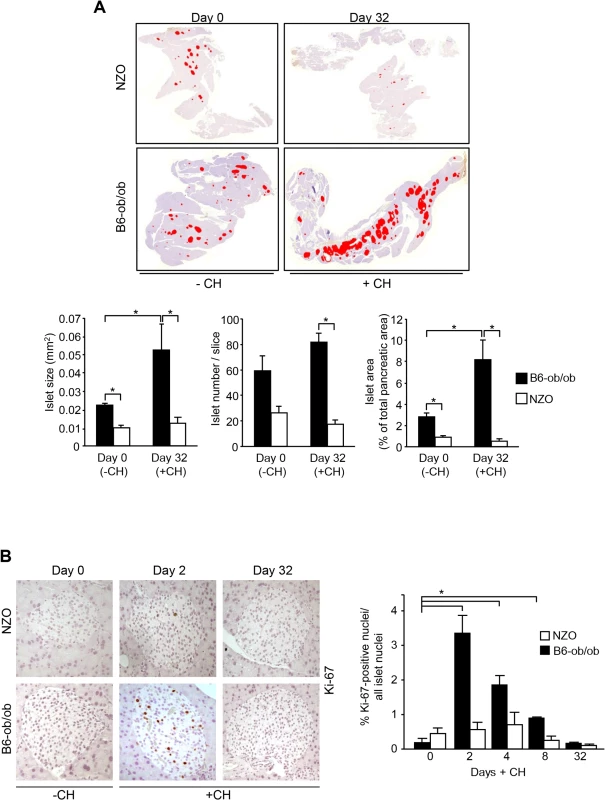

We have previously reported that a specific dietary regimen consisting of pretreatment with carbohydrate-free diet for 15 weeks and a subsequent intervention with a carbohydrate-containing diet results in completely different reactions in diabetes-susceptible NZO and diabetes-resistant B6-ob/ob mice. NZO mice develop hyperglycemia (20.2 ± 2.2 mM blood glucose at day 16) and lose most of their beta-cells by day 32 (Fig 1A, upper panels), whereas B6-ob/ob mice were able to compensate after a transient increase in blood glucose concentrations showing 8.0 ± 0.1 mM blood glucose at day 16 [12]. This might be due to a massive islet hyperplasia that was detected at the end of the intervention state as demonstrated in a representative overview of total pancreas sections of mice before and after receiving carbohydrates (Fig 1A, upper panels). Morphometric analysis demonstrated that size of islets in B6-ob/ob mice increased in response to the carbohydrate challenge rather than their number (Fig 1A, lower panels).

Fig. 1. Diabetes resistance of B6-ob/ob mice is conferred by an adaptive islet hyperplasia.

(A) Representative pictures of total pancreas slices from NZO and B6-ob/ob mice stained for insulin (digital red-colouring) before carbohydrate feeding (-CH) at day 0 and after 32 days of carbohydrate (+CH) feeding (upper panel). Morphometric analysis of insulin staining from 3–5 animals per time point performed in 3 cutting planes with regard to islet size (left panel), islet number per slice (middle panel), and islet area as percentage of total pancreatic area (right panel). Data are mean ± s.e.m.; *P≤0.05 (lower panel). (B) Representative immunohistochemical staining of Ki-67 in pancreatic slices from B6-ob/ob and NZO mice at the indicated time points of carbohydrate-free (-CH) or carbohydrate (+CH) feeding (upper panel). Quantification of Ki-67 positive islet cells from B6-ob/ob and NZO mice fed-CH or +CH at the indicated time points. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. of 4–6 animals, calculated from mean values of 3 cutting planes per pancreas; *P<0.05 (lower panel). In order to confirm that the carbohydrate intervention induces proliferation of islet cells of B6-ob/ob mice we determined Ki-67 positive nuclei in pancreatic sections of NZO and B6-ob/ob mice that were treated with carbohydrates for 2, 4, 8, and 32 days. At no time point an induction of proliferation occurred in NZO islets, whereas B6-ob/ob islets showed a transient induction of proliferation. Highest numbers of Ki-67 positive islet cells were detected at day 2, and these numbers dropped to the initial level up to day 32 of treatment (Fig 1B).

Differentially expressed genes in islets of diabetes-prone NZO and diabetes-resistant B6-ob/ob mice

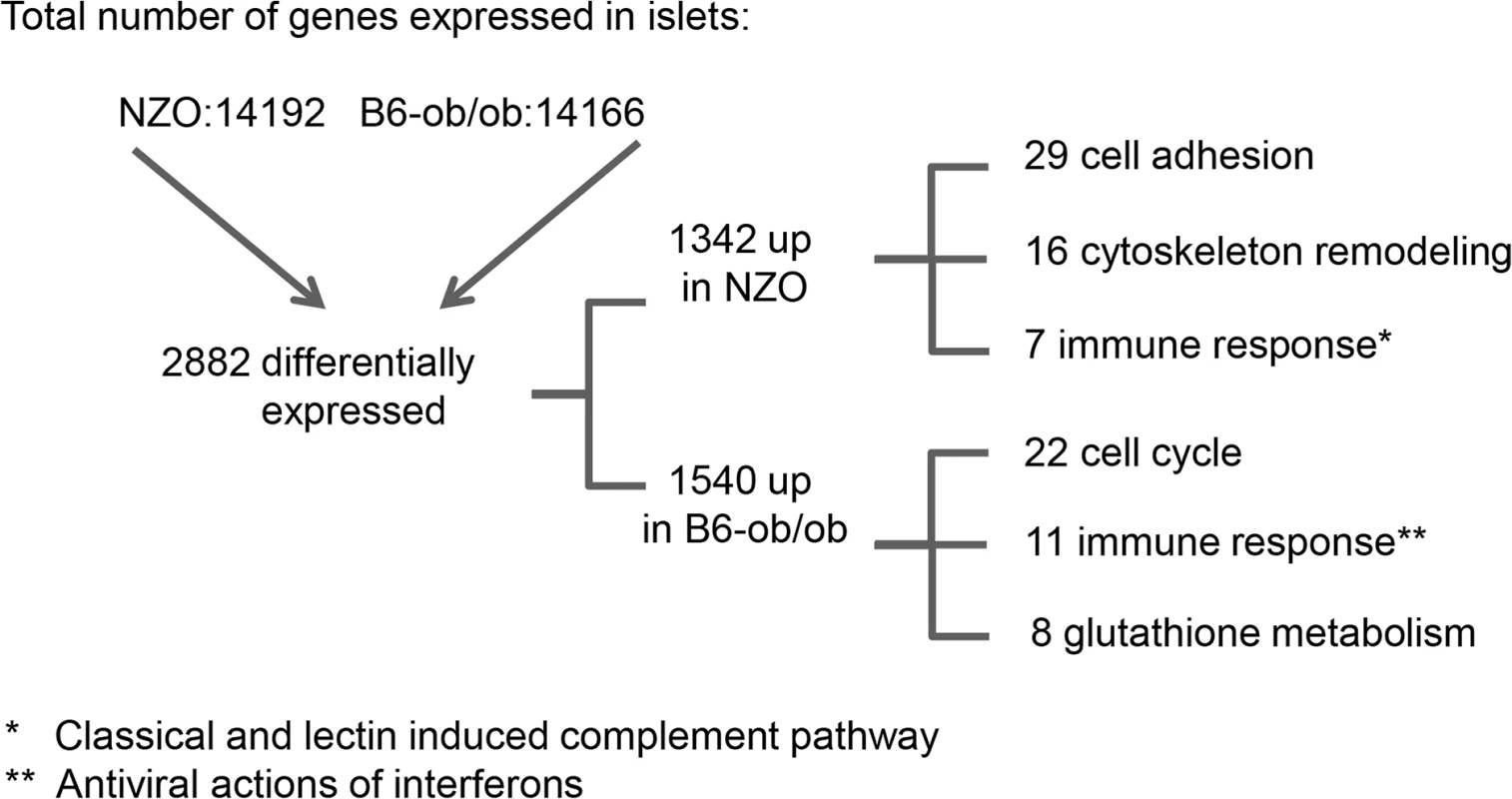

For the identification of genes and pathways that participate in the prevention of diabetes we performed RNAseq based transcriptome analyses of isolated islets of NZO and B6-ob/ob mice two days after the diet switch. MetaCore enrichment pathway analysis with 2882 differentially expressed islet genes in NZO and B6-ob/ob (log2 FC > │0.6│; P<0.05) revealed an upregulation of 22 genes involved in regulation of cell cycle and 8 genes of glutathione metabolism in B6-ob/ob islets, whereas NZO islets exhibited an elevated expression of 29 transcripts mediating cell adhesion and of 7 genes associated with inflammation (Table 1 and Fig 2).

Fig. 2. Beta-cell failure in NZO mice is associated with a modulation of cell adhesion whereas B6-ob/ob mice are protected against diabetes due to an induction of beta-cell cycle.

Overview of results obtained by RNAseq-based transcriptome analysis. Transcriptome of islets from B6-ob/ob and NZO mice that were fed with a carbohydrate-free diet for approximately 15 weeks and subsequently with a carbohydrate-containing diet for 2 days was studied by RNAseq. Indicated are number of genes that are expressed in the islets, those that are differentially expressed (P<0.05, log2 FC > │0.6│) and the quantity of transcripts that are enriched in the indicated pathway as detected by MetaCore. Tab. 1. Main pathways up-regulated by carbohydrate feeding in B6-ob/ob and NZO mice as revealed by MetaCore enrichment pathway analysis.

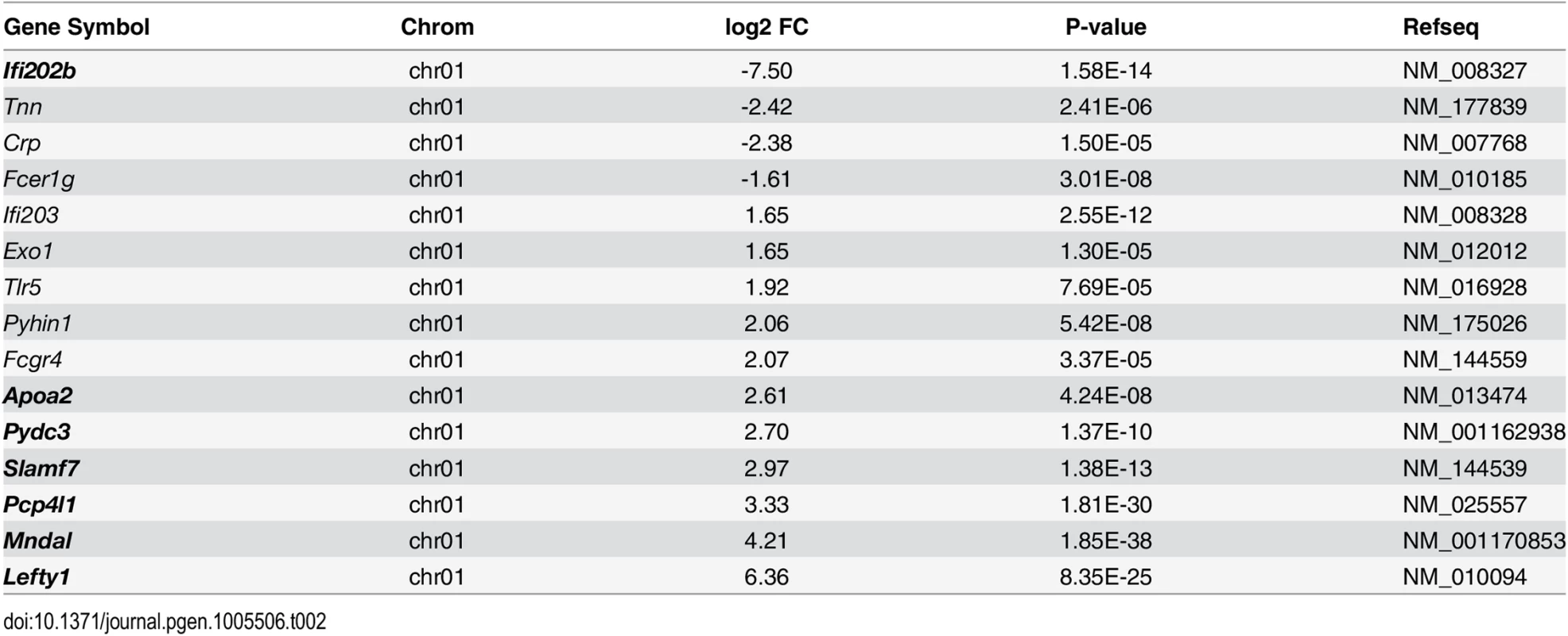

Shown are clusters of the main pathways upregulated in either B6-ob/ob (upper table) or NZO (lower table) islets in combination with the respective genes to be affected and their false discovery rate (FDR). Projection of differentially expressed islet genes to the QTL Nob3

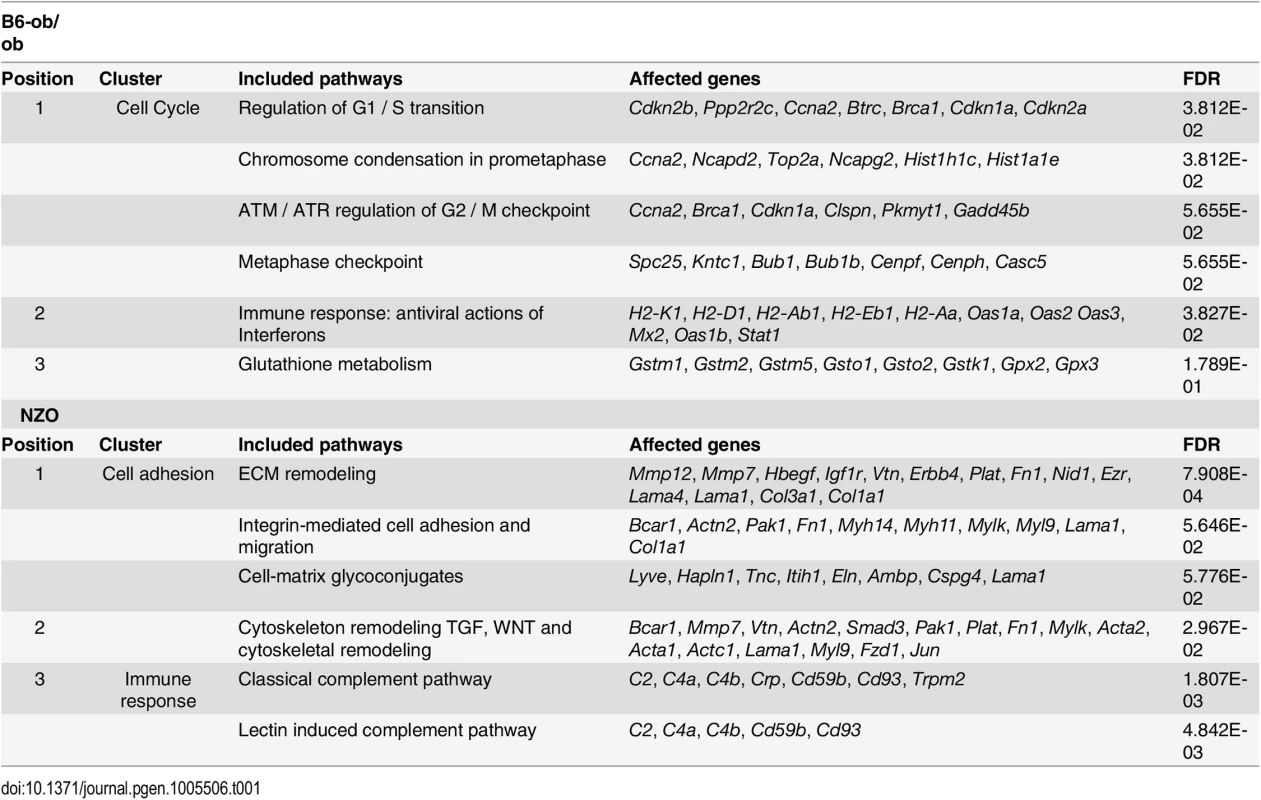

In order to identify the genes responsible for the diabetes resistance of B6-ob/ob and the diabetes sensitivity of NZO mice we projected the differentially expressed islet genes to the major diabesity QTL we have recently identified in a F2 generation of NZO x C57BL/6. This QTL (Nob3) with LODscore values of 16.1, 16.0, 4.0 for body weight, body fat, and blood glucose, respectively was located on the distal part of Chr. 1 [13]. By defining a minimal log2 FC of │1.5│ we found 15 genes to be differentially expressed within the peak region (162.6 to 192.6 Mbp) of Nob3 (Table 2). Among these we found 6 genes with an exclusive expression (<15% rest mRNA) in B6-ob/ob islets (Lefty1, Pcp4l1, Apoa2, Mndal, Slamf7, Pydc3) and one, Ifi202b solely in NZO islets (Fig 3). These fundamental differences were confirmed by qRT-PCR in a new batch of isolated islets (S1 Fig). In contrast to the RNAseq results we detected higher Apoa2 mRNA levels in NZO islets, however, the Apoa2 expression in B6-ob/ob islets was strikingly higher.

Fig. 3. Differentially expressed islet genes in B6-ob/ob and NZO located in a QTL for type 2 diabetes.

Expression levels of the indicated 7 candidates localized within the diabesity-QTL Nob3 on Chr. 1 in islets of NZO and B6-ob/ob mice as detected by RNAseq. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. of 3 animals. Statistics were calculated by edgeR and DEseq; ***P<0.001. Tab. 2. Differentially expressed islet genes in B6-ob/ob and NZO located in a QTL (Nob3) for type 2 diabetes related traits that were detected by linkage studies in (NZOxB6) F2.

Shown are the chromosomal localization, the log2 FC, the P-value and the accession numbers as RefSeq ID. Genes in bold are exclusively expressed either in NZO or B6-ob/ob islets (<15% rest mRNA). Lefty1, Pcp4l1, Apoa2, and Ifi202b modulate proliferation of islet cells

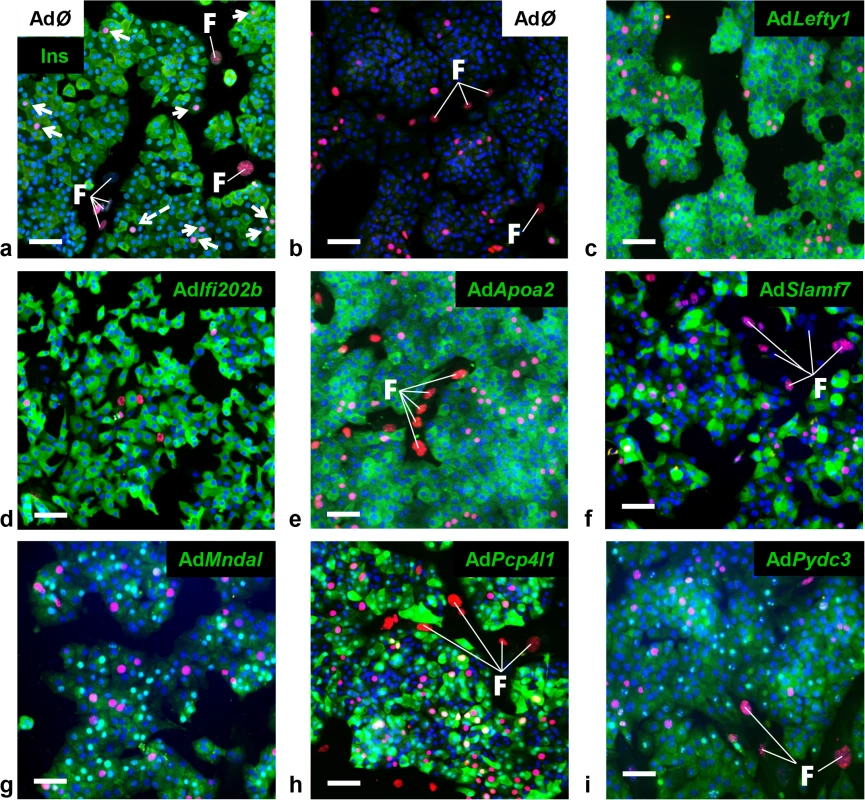

A major difference in the response to the carbohydrate challenge between NZO and B6-ob/ob islets was the lack and induction of proliferation, respectively (Figs 1 and 2). We therefore tested if genes within Nob3 which exhibited the major expression difference in islets of both mice, Ifi202b, Lefty1, Pcp4l1, Apoa2, Mndal, Slamf7, and Pydc3 directly modify islet cell proliferation. We overexpressed each gene in primary islet cells of B6 mice by adenoviral-mediated infection and subsequently analyzed the proliferation capacity by detecting the BrdU incorporation. In order to estimate the levels of beta-cells within primary islet cells and to test if beta-cells are able to proliferate we infected cells with an empty virus, incubated the cells with BrdU and performed a co-staining of BrdU and insulin 72 h later (Fig 4A). As expected, most of the cells were beta-cells and could be distinguished from fibroblasts due to their different shape.

Fig. 4. Detection of BrdU positive primary islet cells overexpressing candidate genes.

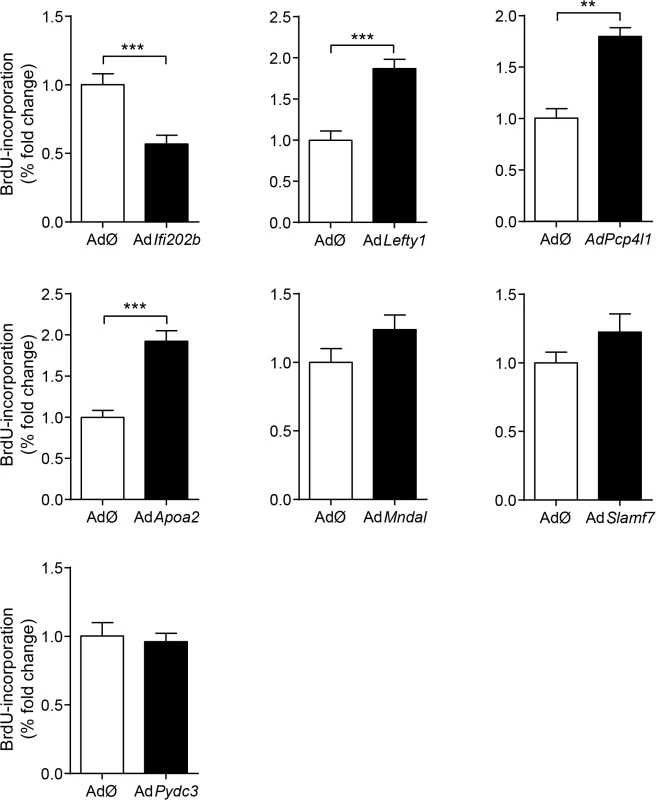

Representative immunocytochemical stainings of dispersed B6 islet cells infected with empty virus (AdØ) as control or adenoviruses expressing the designated genes followed by a 72 h BrdU labeling period. (a) Co-staining of insulin (Ins; green) and BrdU (magenta). White arrows indicate BrdU-positive beta-cells; white dashed arrow indicates BrdU-positive non-beta-cells. (b-i) Co-staining of the myc-tag of indicated proteins (b: control; c: Lefty1, d: Ifi202b, e: ApoA2; f: Slamf7 g: Mndal; h: Pcp4l1; i: Pydc3; green) and BrdU (magenta). The infection rate was between 40 and 90%. Large nuclei are fibroblast-like cells that were left out in any morphometry (white F). Blue: DNA / nuclei. Scale bar: 50 μm. We next infected primary islet cells with viruses encoding for ApoA2, Lefty1, Pcp4l1, Mndal, Slamf7, Ifi202b, and Pydc3 in combination with BrdU incorporation. The overexpression of each candidate was visualized by immunostaining of the respective myc-tag; the infection rate was between 40 and 90% (Fig 4B–4I). Notably, every islet cell culture was accompanied by a growth of fibroblast-like cells, however, as these cells started to grow after virus treatment they were not infected and thereby not myc-positive (Fig 4). Presumably, according to individual differences of islet isolation, digestion, and growth the BrdU incorporation rate varied between the experiments in a range from 1.2 to 7.4% (mean: 3.6 ± 0.6%). In most cases BrdU was detected in insulin-positive cells [95% (AdØ), 96% (AdApoa2), 93% (AdLefty1), 91% (AdPcp4l1), 88% (AdMndal), 93% (AdSlamf7), 91% (AdIfi202b), and 94% (AdPydc3)]. Infection of cells with the Lefty1, Pcp4l1, and Apoa2 encoding viruses increased BrdU incorporation by 87%, 80%, and 92%, respectively; overexpression of Ifi202b decreased the number of BrdU positive cells by 43%. All other candidates were without effect (Fig 5).

Fig. 5. Effects of Ifi202, Lefty1, Pcp4l1, Apoa2, Mndal, Slamf7, and Pydc3 on beta-cell proliferation.

Effects of overexpression of indicated genes on BrdU incorporation in primary islet cells of B6 mice. Islets of B6 mice were isolated, dispersed and infected with adenoviruses encoding for the indicated genes. After infection, BrdU was applied for 72 h. For each candidate between 37,000 and 92,000 myc-expressing cells were evaluated. Due to variations in absolute primary islet cell proliferation depending on cell number and proper digestion, data are presented as fold change to control. Data are mean ± s.e.m. of 3–5 independent experiments **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Genetic association of human LEFTY1 with altered insulin release

Previous human studies have linked type 2 diabetes traits to chr. 1q21-24 in multiple samples [14]. It was shown that seven variants increased the diabetes risk significantly through 5 pairs of interactions. One significant variant pair was a SNP in APOA2 (rs6413453) interacting with calsequestrin-1 (CASQ1; rs617698) [14]. As no association was described for LEFTY1 so far we tested a population of 1,865 individuals with a median age of ~39 years and a BMI of 28.5 kg/m² that was recruited from the Tübingen Family (TUEF) study for type 2 diabetes and characterized before [15]. The participants were genotyped for 10 SNPs tagging the LEFTY1 gene and 2 kb of its 5’-flanking region for association analysis. After adjusting for gender, age, and oGTT-derived insulin sensitivity the minor T-allele of rs3806259 was nominally associated with elevated insulin levels during oral glucose tolerance tests (P = 0.0034), whereas the minor allele of rs360060 was nominally associated with a lower insulin release (P = 0.0052; S2 Fig). Both SNPs were also nominally associated with elevated (P = 0.0593) and reduced (P = 0.0111) C-peptide release, respectively.

Discussion

The present data demonstrated that islets of diabetes-resistant and diabetes-prone mouse strains respond inversely to a glucose challenge: In B6-ob/ob islets, the induction of proliferation resulted in a strong increase in beta-cell mass, which appears to be responsible for an increase in plasma insulin concentration and a sufficient control of blood glucose even under glucotoxic conditions, whereas NZO islets lack the ability to initiate cell cycle progression and to maintain the survival pathway. We identified 7 genes within the diabesity QTL Nob3 which exhibit a nearly exclusive expression in islets of either diabetes-susceptible or diabetes-resistant mice. Three genes, Lefty1, Pcp4l1, and Apoa2 are the most likely candidates to suppress and one gene, Ifi202b to accelerate T2D and beta-cell failure in mice.

To clarify the genetic basis of the inverse reaction of NZO and B6-ob/ob islets on the glucose challenge and to identify diabetes suppressor and enhancer genes we aligned the transcriptome data to the major susceptibility locus identified in former association studies from a NZOxC57BL/6J cross, the Nob3 with a LOD score of 16 for adiposity and of 4 for hyperglycemia [13]. In total, 15 differentially expressed islet genes are located in the Nob3. Focusing on transcripts with the strongest effect revealed six genes (ApoA2, Lefty1, Mndal, Pcp4l1, Pycd3, and Slamf7) to be exclusively expressed in B6-ob/ob and one, Ifi202 in NZO islets. The most prominent molecular alterations were identified for Ifi202b and Lefty1. Ifi202b which was recently identified as an obesity gene in our group by positional cloning carries a microdeletion that includes the promoter and the first exon of Ifi202b and results in a loss of Ifi202b expression in most tissues from B6 mice such as white adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscle [5], and as shown here, also in islets. Since the overexpression of Ifi202b in primary islet cells suppressed proliferation we conclude that it participates in the inability of NZO mice to compensate with an increased beta-cell mass when blood glucose levels rise. Consistent with this conclusion, Clarke et al. (2010) demonstrated that the overexpression of IFI16, a human orthologue of Ifi202b, decreases cellular proliferation by growth arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle [16].

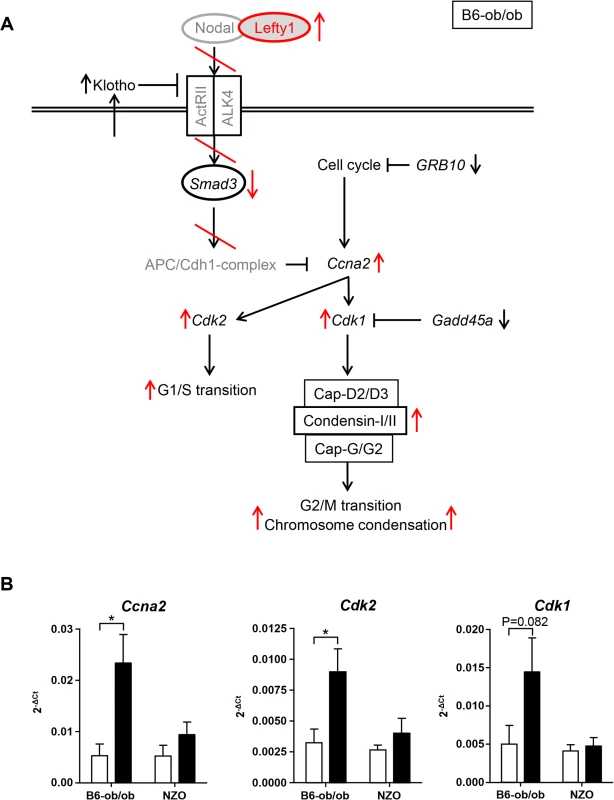

Lefty1, one candidate exclusively expressed in islets of diabetes-resistant B6-ob/ob mice, is an atypical member of the TGF-β family that inhibits Nodal by direct binding to Nodal [17–19]. Recently, Zhang et al. (2008) reported that Nodal and Lefty1 are expressed in the pancreas during embryogenesis and islet regeneration and demonstrated that Lefty1 activates MAPK and AKT in vitro [20]. Our in vitro studies in primary islet cells clearly supported that Lefty1 expression increases proliferation as detected by an increased BrdU incorporation. As Lefty1 is a central regulator of the Smad3 pathway by antagonizing Nodal, we screened our RNAseq and pathway enrichment data for downstream transcripts and indeed found several targets exhibiting an altered expression as indicated in Fig 6A. Nodal activates Smad3, a transcription factor which exhibits a higher expression in NZO than in B6-ob/ob islets (Figs 6A and S3). Smad3 is a tumor suppressor which inhibits cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis [21]. Accordingly, the lower expression of Smad3 in B6-ob/ob islets as a consequence of the presence of Lefty1 could trigger beta-cell proliferation in this diabetes-resistant model (Fig 6A). Specifically, in pancreatic beta-cells Smad3 activation was shown to promote the Cdc25a ubiquitination and degradation via two ubiquitin ligases, the SCFbeta-TrCP-complex and the anaphase-promoting complex (APCCdh1) [22]. Cyclin A2 (Ccna2), another target to be suppressed by the APCCdh1-complex [23,24], is elevated specifically in B6-ob/ob islets in response to carbohydrate feeding and plays a pivotal role in cell-cycle regulation together with the targets Cdk1 and Cdk2 that are also upregulated as determined by qRT-PCR (Fig 6B) [25]. In contrast, without Lefty1 NZO islets display higher Smad3 levels that might participate in raising the expression of ECM molecules such as collagen and fibronectin [26,27] and an increased expression of Mmp7 and Mmp12 that cleave the ECM proteins vitronectin and laminin (Fig 2 and Table 1).

Fig. 6. Schematic representation of pathways that are affected in B6-ob/ob and NZO islets.

(A) Based on pathway analysis performed with differentially expressed genes detected by RNAseq of B6-ob/ob and NZO islets the Lefty/Nodal/Smad3 pathway appears to play a central role for the initiation of beta-cell proliferation in B6-ob/ob. Red arrows and lines indicate the regulation of signaling molecules in B6-ob/ob beta-cells in response to Lefty1. The presence of Lefty1 inhibits Nodal signaling via the ActRII/ALK4 receptor leading to a reduced activity of the anti-proliferative protein Smad3 and ultimately to an induction of proliferation via Cyclin A2 (Ccna2), Cdk2 and Cdk1. Proteins in grey indicate candidates that were not significantly different in the RNAseq analysis. Black arrows indicate the regulation (RNAseq) of additional molecules that could be involved in the pathway. (B) Expression of the indicated cell-cycle transcripts in islets of NZO and B6-ob/ob mice before and after feeding carbohydrates for 2 days as detected by qRT-PCR. Data are mean ± s.e.m. of 4–6 animals; *P≤0.05. We found that two SNPs in human LEFTY1 were nominally associated with altered insulin release in a glucose tolerance test, but not with glycaemia or diabetes. This association seems to suggest that LEFTY1 could be a minor contributor to the pathogenesis of the human disease. However, the finding needs validation in an independent study before a definitive conclusion can be drawn. No significant association between diabetes-related traits and the genotype of 15 SNPs in IFI16, the human orthologue of Ifi202b, was found.

Besides Lefty1, Apoa2 showed an excessive expression in the B6-ob/ob islet and in primary islet cells also a positive effect on proliferation. In fact SNPs in human APOA2 were shown to associate with type 2 diabetes in a Utah case-control sample [14]. However, this finding was not confirmed in French Caucasian subjects [28]. Pcp4l1 (Purkinje cell protein 4 like 1) was also sufficient to increase BrdU incorporation in primary islet cells. Little is known about the function of Pcp4l1. It is described to be expressed during early brain development where it is localized to the midbrain-hindbrain boundary in a pattern that partially overlaps with Wnt1, Pax2 and Fgf8 expression domains [29]. Its closest related protein is Pcp4/PEP-19, a calmodulin-binding protein exhibiting a neuronal IQ motif. However, in contrast to Pcp4/PEP-19, Pcp4l1 lacks the capacity of calmodulin binding presumably due to a nine-residue glutamic acid-rich sequence that is located in proximity to the IQ motif [30]. A link of Pcp4l1 and diabetes has not been described so far.

In summary, our data indicate that Lefty1, Apoa2, Pcp4l1 and Ifi202b modify beta-cell proliferation, and suggest that the alteration of their expression contributes to the development of severe diabetes in the NZO mouse strain.

Material and Methods

Experimental animals

Male NZO/HIBomDife mice (R. Kluge, German Institute of Human Nutrition, Nuthetal, Germany) from our own colony and male B6.V-Lepob/ob/JBomTac (ob/ob) mice (Charles River Laboratories, Italy) were housed in groups of at most five per cage (type II/III macrolon) at a temperature of 21 ± 2°C with a 12 : 12 h light-dark cycle (lights on at 6 : 00 a.m.). Animals had free access to food and water at any time.

Diets and study design

Starting at the age of 5 weeks onwards, all mice received a carbohydrate-free diet (-CH) containing 68% fat (w/w) and 20% protein (w/w) with a total metabolisable energy of 29.3 kJ/g. At the age of 18 ± 1 weeks, subgroups of the animals received a carbohydrate-enriched diet (+CH) containing 28% fat (w/w), 20% protein (w/w) and 40% (w/w) metabolisable carbohydrates for either 48 hours or 32 days. The metabolisable energy content of the +CH was 21.9 kJ/g. Due to the soft texture of the diets mice had access to wooden gnawing sticks in order to avoid excessive teeth growth. The ingredients of the diets are given in S1 Table.

Immunohistochemistry of pancreatic islets

Pancreatic tissue excised immediately after Isofluran anesthesia, was fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 24 h and embedded in paraffin according to standard procedures. Longitudinal serial sections (2–3 μm thickness, sampling intervals 100 μm) were prepared. After re-hydration, slices were incubated with primary antibodies against insulin (1 : 50,000; 1 h; room temperature; Sigma) and Ki-67 (1 : 50; overnight; 4°C; Dako; Hamburg; Germany). Bound primary antibodies were detected with Histofine Immuno-POD Polymer (Nichirei Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan) against mouse or rat, followed by Diaminobenzidine (DAB) incubation for visualization of protein localization. Detection of apoptotic cells by a TUNEL-staining was performed by the ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Billerica, US) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Microscopic investigation and photo documentation were performed with the combined light and fluorescence microscope ECLIPSE E-100 (Nikon, Düsseldorf, Germany) in combination with video camera equipment (CCD-1300CB, Vosskühler, Osnabrück, Germany) and the analysis system NIS elements (Nikon). Total pancreas photographs were made by a MIRAX MIDI scanner (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and evaluated by a software package (AxioVision, Zeiss).

Quantitative analysis of islet stainings

Morphometric analyses of Ki-67 staining were performed by counting the number of positive nuclei in 3 sectional planes of one pancreas with the help of the analysis software NIS elements (Nikon). Mean values derived from each individual mouse were used to calculate mean ± s.e.m. (4–6 animals in each group). Insulin stainings were used to determine islet size, islet number and islet mass of B6-ob/ob and NZO mice. Similarly, quantifications were made from 3 sectional planes of one pancreas and means from each animal were used to calculate mean ± s.e.m. (3–5 animals per group). This analysis was realized by using the AxioVision software package (Zeiss). All morphometric quantifications were conducted via an unbiased stereological approach.

Islet isolation and transcriptome analysis

Isolation of islets was performed by a modified protocol of Gotoh et al. (1990) from 18 ± 1 week old NZO and B6-ob/ob mice [31]. Briefly, the pancreas was perfused by injection of 3 ml of Collagenase-P (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) (1 mg/mL) in Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS) also containing 25 mM HEPES and 0.5% (w/v) BSA into the common bile duct. Subsequently, the perfused pancreas was digested in 2 ml of collagenase solution for 8 to 10 min at 37°C. With the help of a cannula (18G x 11’2) islets were mechanically detached from exocrine parts, and washed for several times with HBSS and RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (PeSt). Islets were passaged for several times in RPMI 1640 by hand-picking and finally collected in Eppendorf tubes. Total islet RNA preparation was performed with the RNAqueous-Micro Kit (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany). In order to apply high-quality RNA for RNAseq analysis we assessed RNA integrity by using a Bioanalyzer and an appropriate kit (RNA6000 nano kit, Agilent, Santa Clara, USA). All preparations were made according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Only RNA with a minimal RNA integrity number of 8.0 (RIN) was used. RNA concentration was measured in 1 μL with a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop ND-100 UV/Vis, PEQLAB, Erlangen, Germany) at 260 nm. RNA sequencing and evaluation of data was performed by LGC genomics (Berlin, Germany).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total islet-RNA of NZO and B6-ob/ob mice fed with the carbohydrate-free diet up to the age of 18 weeks and with or without the carbohydrate-containing diet for 2 days was isolated with the RNAqueous-Micro Kit (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany). Subsequently, first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with the whole amount of RNA, random hexamer primer and GoScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). qRT-PCR was performed with 12.5 ng cDNA in an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-time PCR system with TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) and the TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix. Data were normalized to the expression of cyclophilin (Ppia) as endogenous control (ΔCt-Method) [32].

Overexpression of candidates in primary islet cells and BrdU assay

For overexpression of candidates in primary islet cells islets from C57BL/6 mice fed a high-fat diet until an age of 20 ± 2 weeks were isolated and recovered for 48 hours in RPMI 1640 (10% FCS, 1% PeSt) in humidified 5% CO2, 95% air at 37°C. Islets were digested with Accutase (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, GB) in a volume of 75 μL per 100 islets for 6 min at 37°C and cells separated by aspirating. The digestion was stopped by addition of RPMI 1640 (10% FCS; 1% PeSt), cells were centrifuged (1000xg, 5 min, RT) and the supernatant removed. Resuspended cells were seeded on poly-L-lysine coated coverslips in 24 well plates at a corresponding amount of 1.5 x 105 cells/well. Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (10% FCS, 1 & PeSt) containing 11 mmol/L glucose for 3–4 days. Infection was carried out by a 24 h incubation with adenoviruses carrying cDNA from Pydc3 (MOI100), Lefty1 (MOI100), Slamf7 (MOI10), Mndal (MOI100), Apoa2 (MOI100), Pcp4l1 (MOI100) (Vector Biolabs) and Ifi202b (MOI500) (ViraQuest, North Liberty, USA) under the control of a CMV-promotor and in conjunction with the corresponding empty viruses. Due to the very low proliferation capacity of primary islet cells BrdU labeling (100 μmol/L) was performed for 72 h after virus infection as described by Tsukiyama and colleagues [33]. Afterwards, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After permeabilization of cell membranes (0.2% saponin), DNA denaturation (2 M HCl) and trypsinization (0.1% trypsin) cells were incubated with primary antibodies against BrdU (1 : 500, 1 h, room temperature; Sigma) plus anti myc-antibody (1 : 500, Santa Cruz, USA). Bound primary antibodies were detected with fluorophor-labeled secondary antibodies against rat (Alexa Fluor546, 1 : 400, Invitrogen) and rabbit (Alexa Fluor488, 1 : 400, Invitrogen) and documented with a confocal microscope (TCS SP-2-Confocal Laser scanning microscope, Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany). Statistical evaluation was performed by blinded quantification of 10–12 photographs of at least 2 coverslips per infection and mean ± s.e.m. was calculated from 4–5 independent experiments.

Human subjects and measurement of insulin release

A study population of 1,865 individuals with complete insulin, C-peptide, and glucose measurements during a standard 5-point oral glucose tolerance test (oGTT) was recruited from the Tübingen Family study for type 2 diabetes [15]. From these data, insulin release was estimated as area under the curve (AUC) insulin0–30 divided by AUC glucose0–30 and as AUC C-peptide0–30 divided by AUC glucose0–30. AUCs were calculated according to the trapezoid method. oGTT-derived insulin sensitivity was calculated as proposed by Matsuda and DeFronzo [34].

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) selection and genotyping

Based on publicly available information from 1000 Genomes (http://browser.1000genomes.org/Homo_sapiens/Info/Index), we analysed the complete human LEFTY1 and IFI16 genes and 2 kb each of their 5’-flanking regions and identified 10 and 15, respectively, non-linked representative SNPs tagging all other common SNPs (minor allele frequency ≥ 0.1) in these loci with r² ≥ 0.8. The tagger function of Haploview 4.2 (http://www.broadinstitute.org. haploview/haploview) was used. The 10 LEFTY1 tagging SNPs, i.e., rs7551003 G>T, rs72754996 G>A, rs193327 C>G, rs3806259 C>T, rs2013363 G>T, rs360074 G>A, rs10915896 C>T, rs360073 G>A, rs360060 G>A, and rs360058 G>T, were all non-coding and located in the 5’-flanking region of the gene. The 15 non-coding IFI16 tagging SNPs were rs72704962 T>C, rs1465175 G>T, rs4657618 C>T, rs1417806 A>C, rs856077 C>A, and rs1417805 T>G in the 5’-flanking region, rs2276404 A>G, rs856064 C>T, and rs12727764 G>T in intron 1, rs2106095 T>A, rs12087333 A>G, rs74122213 T>C, and rs12061401 C>T in intron 6, and rs1633262 T>C and rs1772414 A>G in intron 7 of the gene. The tagging SNPs were genotyped in blood-derived genomic DNA using Sequenom’s massARRAY system (Sequenom, Hamburg, Germany) or TaqMan allelic discrimination assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Statistics

RNAseq read counts were tested by 2 statistical evaluations (DEseq [35]), and edgeR [36] of the R package in combination with an error correction by Benjamini-Hochberg. All comparisons were considered significantly different at P<0.05 and a log2 FC >│0.6│and │1.5│, respectively. Differences in morphometric analysis, qRT-PCRs and BrdU-Assays were tested with the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test and corrected for multiple comparisons by Dunn’s. For human association studies skewed data were loge-transformed in order to approximate normal distribution. Multiple linear regression analysis (standard least squares method) was performed with insulin release as outcome variable, the SNP genotype (in the additive inheritance model) as independent variable, and gender, age, and insulin sensitivity as confounding variables. To account for multiple testing (25 SNPs tested in parallel), a Bonferroni-corrected P-value <0.002 was considered statistically significant. For these analyses, JMP 10.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used.

Ethics statement

All animals were kept in accordance with the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. All experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the State Ministry of Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry (State of Brandenburg, Germany). The approval numbers were: V3-2347-31-2011 and 2347-26-2014.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. DeFronzo RA (2010) Insulin resistance, lipotoxicity, type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis: the missing links. The Claude Bernard Lecture 2009. Diabetologia 53 : 1270–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1684-1 20361178

2. Coleman DL (1978) Obese and diabetes: two mutant genes causing diabetes-obesity syndromes in mice. Diabetologia 14 : 141–148. 350680

3. Leiter EH (2002) Mice with targeted gene disruptions or gene insertions for diabetes research: problems, pitfalls, and potential solutions. Diabetologia 45 : 296–308. 11914735

4. Chadt A, Leicht K, Deshmukh A, Jiang LQ, Scherneck S, et al. (2008) Tbc1d1 mutation in lean mouse strain confers leanness and protects from diet-induced obesity. Nature genetics 40 : 1354–1359. doi: 10.1038/ng.244 18931681

5. Vogel H, Scherneck S, Kanzleiter T, Benz V, Kluge R, et al. (2012) Loss of function of Ifi202b by a microdeletion on chromosome 1 of C57BL/6J mice suppresses 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 expression and development of obesity. Human molecular genetics 21 : 3845–3857. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds213 22692684

6. Scherneck S, Nestler M, Vogel H, Bluher M, Block MD, et al. (2009) Positional cloning of zinc finger domain transcription factor Zfp69, a candidate gene for obesity-associated diabetes contributed by mouse locus Nidd/SJL. PLoS genetics 5: e1000541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000541 19578398

7. Meyre D, Farge M, Lecoeur C, Proenca C, Durand E, et al. (2008) R125W coding variant in TBC1D1 confers risk for familial obesity and contributes to linkage on chromosome 4p14 in the French population. Human molecular genetics 17 : 1798–1802. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn070 18325908

8. Stone S, Abkevich V, Russell DL, Riley R, Timms K, et al. (2006) TBC1D1 is a candidate for a severe obesity gene and evidence for a gene/gene interaction in obesity predisposition. Human molecular genetics 15 : 2709–2720. 16893906

9. Jurgens HS, Schurmann A, Kluge R, Ortmann S, Klaus S, et al. (2006) Hyperphagia, lower body temperature, and reduced running wheel activity precede development of morbid obesity in New Zealand obese mice. Physiological genomics 25 : 234–241. 16614459

10. Kluth O, Mirhashemi F, Scherneck S, Kaiser D, Kluge R, et al. (2011) Dissociation of lipotoxicity and glucotoxicity in a mouse model of obesity associated diabetes: role of forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) in glucose-induced beta cell failure. Diabetologia 54 : 605–616. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1973-8 21107520

11. Mirhashemi F, Kluth O, Scherneck S, Vogel H, Kluge R, et al. (2008) High-fat, carbohydrate-free diet markedly aggravates obesity but prevents beta-cell loss and diabetes in the obese, diabetes-susceptible db/db strain. Obesity facts 1 : 292–297. doi: 10.1159/000176064 20054191

12. Kluth O, Matzke D, Schulze G, Schwenk RW, Joost HG, et al. (2014) Differential transcriptome analysis of diabetes-resistant and-sensitive mouse islets reveals significant overlap with human diabetes susceptibility genes. Diabetes 63 : 4230–4238. doi: 10.2337/db14-0425 25053586

13. Vogel H, Nestler M, Ruschendorf F, Block MD, Tischer S, et al. (2009) Characterization of Nob3, a major quantitative trait locus for obesity and hyperglycemia on mouse chromosome 1. Physiological genomics 38 : 226–232. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00011.2009 19470805

14. Hasstedt SJ, Chu WS, Das SK, Wang H, Elbein SC (2008) Type 2 diabetes susceptibility genes on chromosome 1q21-24. Annals of human genetics 72 : 163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00416.x 18269685

15. Staiger H, Bohm A, Scheler M, Berti L, Machann J, et al. (2013) Common genetic variation in the human FNDC5 locus, encoding the novel muscle-derived 'browning' factor irisin, determines insulin sensitivity. PloS one 8: e61903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061903 23637927

16. Clarke CJ, Hii LL, Bolden JE, Johnstone RW (2010) Inducible activation of IFI 16 results in suppression of telomerase activity, growth suppression and induction of cellular senescence. Journal of cellular biochemistry 109 : 103–112. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22386 19885868

17. Chen C, Shen MM (2004) Two modes by which Lefty proteins inhibit nodal signaling. Current biology: CB 14 : 618–624. 15062104

18. Cheng SK, Olale F, Brivanlou AH, Schier AF (2004) Lefty blocks a subset of TGFbeta signals by antagonizing EGF-CFC coreceptors. PLoS biology 2: E30. 14966532

19. Hamada H, Meno C, Watanabe D, Saijoh Y (2002) Establishment of vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Nature reviews Genetics 3 : 103–113. 11836504

20. Zhang YQ, Sterling L, Stotland A, Hua H, Kritzik M, et al. (2008) Nodal and lefty signaling regulates the growth of pancreatic cells. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 237 : 1255–1267.

21. Millet C, Zhang YE (2007) Roles of Smad3 in TGF-beta signaling during carcinogenesis. Critical reviews in eukaryotic gene expression 17 : 281–293. 17725494

22. Ray D, Terao Y, Nimbalkar D, Chu LH, Donzelli M, et al. (2005) Transforming growth factor beta facilitates beta-TrCP-mediated degradation of Cdc25A in a Smad3-dependent manner. Molecular and cellular biology 25 : 3338–3347. 15798217

23. Fang G, Yu H, Kirschner MW (1998) Direct binding of CDC20 protein family members activates the anaphase-promoting complex in mitosis and G1. Molecular cell 2 : 163–171. 9734353

24. Glotzer M, Murray AW, Kirschner MW (1991) Cyclin is degraded by the ubiquitin pathway. Nature 349 : 132–138. 1846030

25. Johnson DG, Walker CL (1999) Cyclins and cell cycle checkpoints. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology 39 : 295–312. 10331086

26. Rozen-Zvi B, Hayashida T, Hubchak SC, Hanna C, Platanias LC, et al. (2013) TGF-beta/Smad3 activates mammalian target of rapamycin complex-1 to promote collagen production by increasing HIF-1alpha expression. American journal of physiology Renal physiology 305: F485–494. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00215.2013 23761672

27. Verrecchia F, Mauviel A (2002) Transforming growth factor-beta signaling through the Smad pathway: role in extracellular matrix gene expression and regulation. The Journal of investigative dermatology 118 : 211–215. 11841535

28. Duesing K, Charpentier G, Marre M, Tichet J, Hercberg S, et al. (2009) Evaluating the association of common APOA2 variants with type 2 diabetes. BMC medical genetics 10 : 13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-13 19216768

29. Bulfone A, Caccioppoli C, Pardini C, Faedo A, Martinez S, et al. (2004) Pcp4l1, a novel gene encoding a Pcp4-like polypeptide, is expressed in specific domains of the developing brain. Gene expression patterns: GEP 4 : 297–301. 15053978

30. Morgan MA, Morgan JI (2012) Pcp4l1 contains an auto-inhibitory element that prevents its IQ motif from binding to calmodulin. Journal of neurochemistry 121 : 843–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07745.x 22458599

31. Gotoh M, Ohzato H, Dono K, Kawai M, Yamamoto H, et al. (1990) Successful islet isolation from preserved rat pancreas following pancreatic ductal collagenase at the time of harvesting. Hormone and metabolic research Supplement series 25 : 1–4.

32. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25 : 402–408. 11846609

33. Tsukiyama S, Matsushita M, Matsumoto S, Morita T, Kobayashi S, et al. (2006) Transduction of exogenous constitutively activated Stat3 into dispersed islets induces proliferation of rat pancreatic beta-cells. Tissue engineering 12 : 131–140. 16499450

34. Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA (1999) Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes care 22 : 1462–1470. 10480510

35. Anders S, Huber W (2010) Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome biology 11: R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106 20979621

36. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010) edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26 : 139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 19910308

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek The Chromatin Protein DUET/MMD1 Controls Expression of the Meiotic Gene during Male Meiosis inČlánek Tissue-Specific Gain of RTK Signalling Uncovers Selective Cell Vulnerability during Embryogenesis

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 9- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- IVF a rakovina prsu – zvyšují hormony riziko vzniku rakoviny?

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Retraction: RNAi-Dependent and Independent Control of LINE1 Accumulation and Mobility in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Signaling from Within: Endocytic Trafficking of the Robo Receptor Is Required for Midline Axon Repulsion

- A Splice Region Variant in Lowers Non-high Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Protects against Coronary Artery Disease

- The Chromatin Protein DUET/MMD1 Controls Expression of the Meiotic Gene during Male Meiosis in

- A NIMA-Related Kinase Suppresses the Flagellar Instability Associated with the Loss of Multiple Axonemal Structures

- Slit-Dependent Endocytic Trafficking of the Robo Receptor Is Required for Son of Sevenless Recruitment and Midline Axon Repulsion

- Expression of Concern: Protein Under-Wrapping Causes Dosage Sensitivity and Decreases Gene Duplicability

- Mutagenesis by AID: Being in the Right Place at the Right Time

- Identification of as a Genetic Modifier That Regulates the Global Orientation of Mammalian Hair Follicles

- Bridges Meristem and Organ Primordia Boundaries through , , and during Flower Development in

- Evaluating the Performance of Fine-Mapping Strategies at Common Variant GWAS Loci

- KLK5 Inactivation Reverses Cutaneous Hallmarks of Netherton Syndrome

- Differential Expression of Ecdysone Receptor Leads to Variation in Phenotypic Plasticity across Serial Homologs

- Receptor Polymorphism and Genomic Structure Interact to Shape Bitter Taste Perception

- Cognitive Function Related to the Gene Acquired from an LTR Retrotransposon in Eutherians

- Critical Function of γH2A in S-Phase

- Arabidopsis AtPLC2 Is a Primary Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C in Phosphoinositide Metabolism and the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response

- XBP1-Independent UPR Pathways Suppress C/EBP-β Mediated Chondrocyte Differentiation in ER-Stress Related Skeletal Disease

- Integration of Genome-Wide SNP Data and Gene-Expression Profiles Reveals Six Novel Loci and Regulatory Mechanisms for Amino Acids and Acylcarnitines in Whole Blood

- A Genome-Wide Association Study of a Biomarker of Nicotine Metabolism

- Cell Cycle Regulates Nuclear Stability of AID and Determines the Cellular Response to AID

- A Genome-Wide Association Analysis Reveals Epistatic Cancellation of Additive Genetic Variance for Root Length in

- Tissue-Specific Gain of RTK Signalling Uncovers Selective Cell Vulnerability during Embryogenesis

- RAB-10-Dependent Membrane Transport Is Required for Dendrite Arborization

- Basolateral Endocytic Recycling Requires RAB-10 and AMPH-1 Mediated Recruitment of RAB-5 GAP TBC-2 to Endosomes

- Dynamic Contacts of U2, RES, Cwc25, Prp8 and Prp45 Proteins with the Pre-mRNA Branch-Site and 3' Splice Site during Catalytic Activation and Step 1 Catalysis in Yeast Spliceosomes

- ARID1A Is Essential for Endometrial Function during Early Pregnancy

- Predicting Carriers of Ongoing Selective Sweeps without Knowledge of the Favored Allele

- An Interaction between RRP6 and SU(VAR)3-9 Targets RRP6 to Heterochromatin and Contributes to Heterochromatin Maintenance in

- Photoreceptor Specificity in the Light-Induced and COP1-Mediated Rapid Degradation of the Repressor of Photomorphogenesis SPA2 in Arabidopsis

- Autophosphorylation of the Bacterial Tyrosine-Kinase CpsD Connects Capsule Synthesis with the Cell Cycle in

- Multimer Formation Explains Allelic Suppression of PRDM9 Recombination Hotspots

- Rescheduling Behavioral Subunits of a Fixed Action Pattern by Genetic Manipulation of Peptidergic Signaling

- A Gene Regulatory Program for Meiotic Prophase in the Fetal Ovary

- Cell-Autonomous Gβ Signaling Defines Neuron-Specific Steady State Serotonin Synthesis in

- Discovering Genetic Interactions in Large-Scale Association Studies by Stage-wise Likelihood Ratio Tests

- The RCC1 Family Protein TCF1 Regulates Freezing Tolerance and Cold Acclimation through Modulating Lignin Biosynthesis

- The AMPK, Snf1, Negatively Regulates the Hog1 MAPK Pathway in ER Stress Response

- The Parkinson’s Disease-Associated Protein Kinase LRRK2 Modulates Notch Signaling through the Endosomal Pathway

- Multicopy Single-Stranded DNA Directs Intestinal Colonization of Enteric Pathogens

- Recurrent Domestication by Lepidoptera of Genes from Their Parasites Mediated by Bracoviruses

- Three Different Pathways Prevent Chromosome Segregation in the Presence of DNA Damage or Replication Stress in Budding Yeast

- Identification of Four Mouse Diabetes Candidate Genes Altering β-Cell Proliferation

- The Intolerance of Regulatory Sequence to Genetic Variation Predicts Gene Dosage Sensitivity

- Synergistic and Dose-Controlled Regulation of Cellulase Gene Expression in

- Genome Sequence and Transcriptome Analyses of : Metabolic Tools for Enhanced Algal Fitness in the Prominent Order Prymnesiales (Haptophyceae)

- Ty3 Retrotransposon Hijacks Mating Yeast RNA Processing Bodies to Infect New Genomes

- FUS Interacts with HSP60 to Promote Mitochondrial Damage

- Point Mutations in Centromeric Histone Induce Post-zygotic Incompatibility and Uniparental Inheritance

- Genome-Wide Association Study with Targeted and Non-targeted NMR Metabolomics Identifies 15 Novel Loci of Urinary Human Metabolic Individuality

- Outer Hair Cell Lateral Wall Structure Constrains the Mobility of Plasma Membrane Proteins

- A Large-Scale Functional Analysis of Putative Target Genes of Mating-Type Loci Provides Insight into the Regulation of Sexual Development of the Cereal Pathogen

- A Genetic Selection for Mutants Reveals an Interaction between DNA Polymerase IV and the Replicative Polymerase That Is Required for Translesion Synthesis

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Arabidopsis AtPLC2 Is a Primary Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C in Phosphoinositide Metabolism and the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response

- Bridges Meristem and Organ Primordia Boundaries through , , and during Flower Development in

- KLK5 Inactivation Reverses Cutaneous Hallmarks of Netherton Syndrome

- XBP1-Independent UPR Pathways Suppress C/EBP-β Mediated Chondrocyte Differentiation in ER-Stress Related Skeletal Disease

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání