-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Bridges Meristem and Organ Primordia Boundaries through , , and during Flower Development in

The shoot apical meristem is the stem cell pool in plants that gives rise to all above-ground organs including leaves, flowers and fruits. Between the meristem and the newly formed organ primordia, a boundary with specialized cells is formed to separate them. Boundary genes are specifically expressed in boundaries and function in boundary formation and maintenance. Previous studies showed that boundary genes interact with meristem regulators and primordia genes during embryogenesis or leaf development. But whether and how boundaries communicate with meristem and organ primordia during flower development remains largely unknown. Here we combined genetic, molecular and biochemical tools to explore interactions between the boundary gene HANABA TARANU (HAN) and two meristem regulators BREVIPEDICELLUS (BP) and PINHEAD (PNH), and three primordia-specific genes PETAL LOSS (PTL), JAGGED (JAG) and BLADE-ON-PETIOLE (BOP) during flower development. We showed that boundary-expressing HAN communicates with the meristem through PNH, regulates floral organ development via JAG and BOP2, and maintains boundary morphology through CYTOKININ OXIDASE 3 (CKX3)-mediated cytokinin homeostasis. Thus, our findings shed light on the “bridge” role of boundaries between meristem and organ primordia during flower development in Arabidopsis.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005479

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005479Summary

The shoot apical meristem is the stem cell pool in plants that gives rise to all above-ground organs including leaves, flowers and fruits. Between the meristem and the newly formed organ primordia, a boundary with specialized cells is formed to separate them. Boundary genes are specifically expressed in boundaries and function in boundary formation and maintenance. Previous studies showed that boundary genes interact with meristem regulators and primordia genes during embryogenesis or leaf development. But whether and how boundaries communicate with meristem and organ primordia during flower development remains largely unknown. Here we combined genetic, molecular and biochemical tools to explore interactions between the boundary gene HANABA TARANU (HAN) and two meristem regulators BREVIPEDICELLUS (BP) and PINHEAD (PNH), and three primordia-specific genes PETAL LOSS (PTL), JAGGED (JAG) and BLADE-ON-PETIOLE (BOP) during flower development. We showed that boundary-expressing HAN communicates with the meristem through PNH, regulates floral organ development via JAG and BOP2, and maintains boundary morphology through CYTOKININ OXIDASE 3 (CKX3)-mediated cytokinin homeostasis. Thus, our findings shed light on the “bridge” role of boundaries between meristem and organ primordia during flower development in Arabidopsis.

Introduction

Leaves and flowers originate from the shoot apical meristem (SAM), which contains pluripotent stem cells and resides at the tip of each stem. Primordia are initiated from the peripheral zone of the SAM in a predictable pattern, and develop into leaves during the vegetative stage, and into flowers during the reproductive phase. Each flower consists of four concentric whorls of organ types: the protective sepals, the showy petals, the male stamens, and the female carpels [1]. Between the meristem and newly formed leaf or flower primordia, a boundary forms with specialized cells that separate meristematic activity from determinate organ growth [2]. Cells in the boundary have reduced rates of cell division, concave surfaces, elongated shapes, and exhibit low auxin concentration compared to the adjacent cells in meristems or primordia [3–6]. There are two types of boundaries in the developing shoot apices. M-O (meristem-organ) boundaries separate leaf and flower primordia from the SAM, whereas O-O (organ-organ) boundaries develop between individual floral organs and create space between them [2, 7].

Based on boundary-specific expression patterns and mutant defects in boundary formation, organ separation, SAM initiation and maintenance, branching, or floral organ patterning, several transcription factors have been identified as important boundary regulators, including CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDONS 1, 2 and 3 (CUC1, CUC2, CUC3), LATERAL SUPPRESSOR (LAS), LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES (LOB), JAGGED LATERAL ORGANS (JLO), LATERAL ORGAN FUSION (LOF), HANABA TARANU (HAN), SUPERMAN (SUP) and RABBIT EARS (RBE)[5, 8–21]. Interactions have been found between boundary regulators and genes controlling meristem maintenance or primordia development. For example, CUC genes promote SAM formation via the activation of meristem marker SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM), and in return, STM represses CUC expression in the meristem [9, 22]. CUC genes are also inhibited by primordia marker ASYMMETRIC LEAVES 1 (AS1) and AS2 in the organ primordia [23–25]. However, as most boundary studies were performed during embryogenesis or vegetative growth, little is known about how boundary regulators communicate with meristem and organ primordia during the reproductive stage.

The boundary regulator HAN encodes a GATA-3 type transcription factor with a single zinc finger domain and plays a role in Arabidopsis flower development. HAN is expressed at the boundaries between meristem and floral organ primordia and at the boundaries of floral organs [13]. Mutation of HAN leads to fused sepals, and reduced numbers of petals and stamens [13]. The meristem regulator KNAT1 /BREVIPEDICELLUS (BP) encodes a KNOTTED1-LIKE HOMEOBOX (KNOX) class I homeobox gene that is required for inflorescence architecture. Disruption of BP function results in short internodes and pedicels, and downward-oriented siliques [26, 27]. Similarly, ARGONAUTE 10/PINHEAD (PNH), a founding member of the ARGONAUTE family, is a regulator of meristem maintenance that acts by sequestering miR166/165, preventing its incorporation into an ARGONAUTE 1 complex [28–31]. In pnh mutants, phenotypes are pleiotropic including an SAM occupied by pin-like structures, increased numbers of floral organs, and disrupted embryo and ovule development [32]. In primordia, indeterminate meristematic activities are repressed and primordia-specific genes are induced to ensure proper determinate organ development [2, 23, 24]. PETAL LOSS (PTL), JAGGED (JAG) and BLADE-ON-PETIOLE (BOP) belong to the class of primordia-specific genes that regulates flower organ development [32]. PTL is expressed in the margins of developing sepals, petals and stamens, and ensures normal petal initiation by maintaining auxin homeostasis [33, 34]. Loss of function of PTL leads to reduced numbers of petals and disrupted petal orientation [11, 35, 36]. JAG, a putative C2H2 zinc finger transcription factor, expresses in the initiating primordia but not the meristem, and regulates lateral organ development in Arabidopsis [37]. A JAG knockout mutant displays serrated sepals and narrow petals [37, 38]. JAG controls cell proliferation during organ growth by maintaining tissues in an actively dividing state [37], and acts redundantly with NUBBIN, a JAGGED-like gene, to control the shape and size of lateral organs [39]. BOP1/2 specify BTB/POZ domain proteins and express in the base of flower primordia. They function redundantly to control flower and leaf development [17, 40–42]. Loss of function of BOP1 and BOP2 results in increased petal numbers, lack of floral organ abscission and leafy petioles [42–44].

Whether and how boundary genes interact with meristem-related regulators and primordia-specific genes during flower development remains largely unknown. In this study, we combined genetic, molecular and biochemical tools to explore interactions between the boundary gene HAN and two meristem regulators (BP and PNH), and three primordia-specific genes (PTL, JAG and BOP1/2) that function in flower development. We found that HAN plays a central role among these seven regulators in the control of petal development. At the transcriptional level, HAN promotes PNH transcription and represses BP expression, BP represses PNH while PNH positively feeds back on the expression of HAN. At the protein level, HAN physically interacts with PNH and PNH interacts with BP to regulate meristem organization. HAN also interacts with JAG, and directly promotes the expression of JAG and BOP2 to regulate floral organ development. Further, HAN directly stimulates CYTOKININ OXIDASE 3 (CKX3) expression to modulate cytokinin levels in the boundary. Therefore, our data suggest a new link by which HAN communicates with the meristem through PNH, regulates primordia development via JAG and BOP2, and maintains boundary morphology through CKX3-mediated cytokinin homeostasis during flower development in Arabidopsis.

Results

Genetic interactions of HAN with meristem - and primordial-regulators during flower development in Arabidopsis

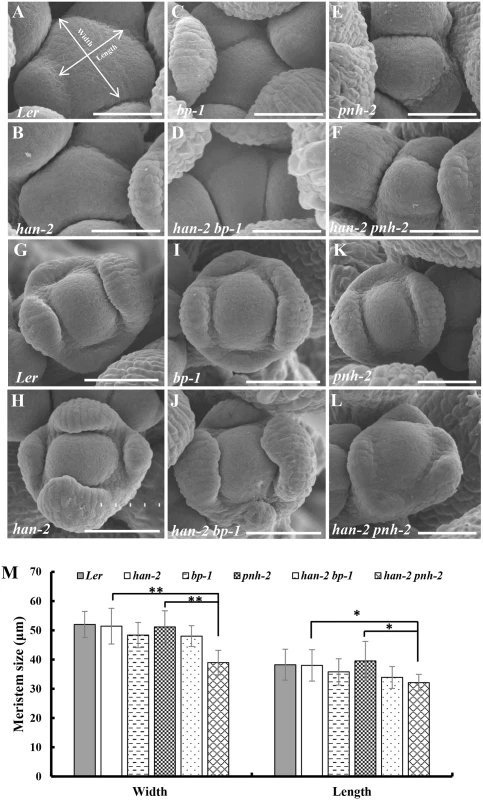

Mutation in HAN results in reduced numbers of petals and stamens, and fused sepals [13]. In contrast to the wild-type flower with four sepals and four petals, the han-2 mutant has an average of only 3.4 sepals and 2.6 petals in the Ler or Col background (Fig 1A–1C, Table 1). In order to explore the potential genetic interactions between HAN, meristem regulators, and primordia-specific genes during flower development, we generated double or triple mutant combinations of han-2 with bp-1, pnh-2, ptl-1, jag-3 and bop1 bop2 (Fig 1 and S1 Fig). Firstly, we explored the genetic interaction of HAN with meristem regulator BP. The bp-1 mutant shows a normal number of floral organs, with downward-pointing flowers and a compact inflorescence (Fig 1D and S1B Fig) [26]. The number of petals and sepals was reduced in a han-2 bp-1 double mutant, with an average of 1.7±0.1 (n = 120) petals (Fig 1E and S1C Fig, Table 1). The phenotype of fused sepals is similar to han-2. Then, we examined the genetic interaction of HAN with PNH, whose mutations result in increased numbers of petals. The average petal number was 4.3±0.1 (n = 40) in the pnh-2 mutant (Fig 1F, Table 1). han-2 pnh-2 double mutants have fewer petals than the han-2 single mutant (Fig 1G and S1D–S1G Fig, Table 1). Therefore, mutation of meristem regulators BP and PNH enhanced the petal loss phenotype of han-2. Given that both BP and PNH are meristem regulators [24, 45], we next explored the phenotypes of meristem organization upon induction of han-2 into bp-1 or pnh-2 mutant background (Fig 2). In inflorescence meristems (IM) and floral meristems (FM), no obvious changes were observed in the meristem organization of the single mutant han-2 and bp-1, or double mutant han-2 bp-1 as compared to the wild-type (Fig 2A–2D, 2G–2J, and 2M). However, mutation of HAN greatly enhanced the smaller and taller IM and FM phenotype in the pnh-2 (Fig 2E and 2F, 2K and 2L, and 2M), suggesting that HAN and PNH coordinatively regulate meristem organization in Arabidopsis.

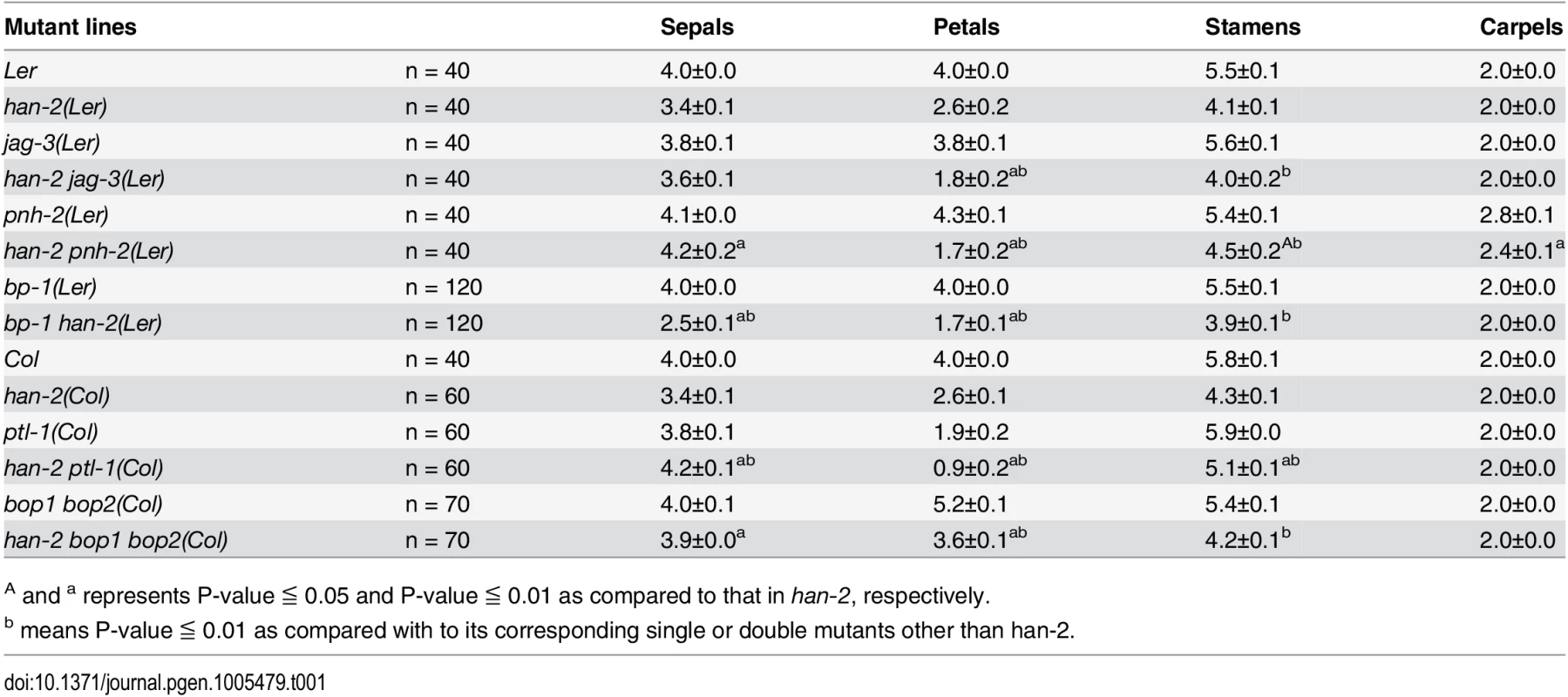

Tab. 1. Characterization of the number of floral organs in different mutant lines.

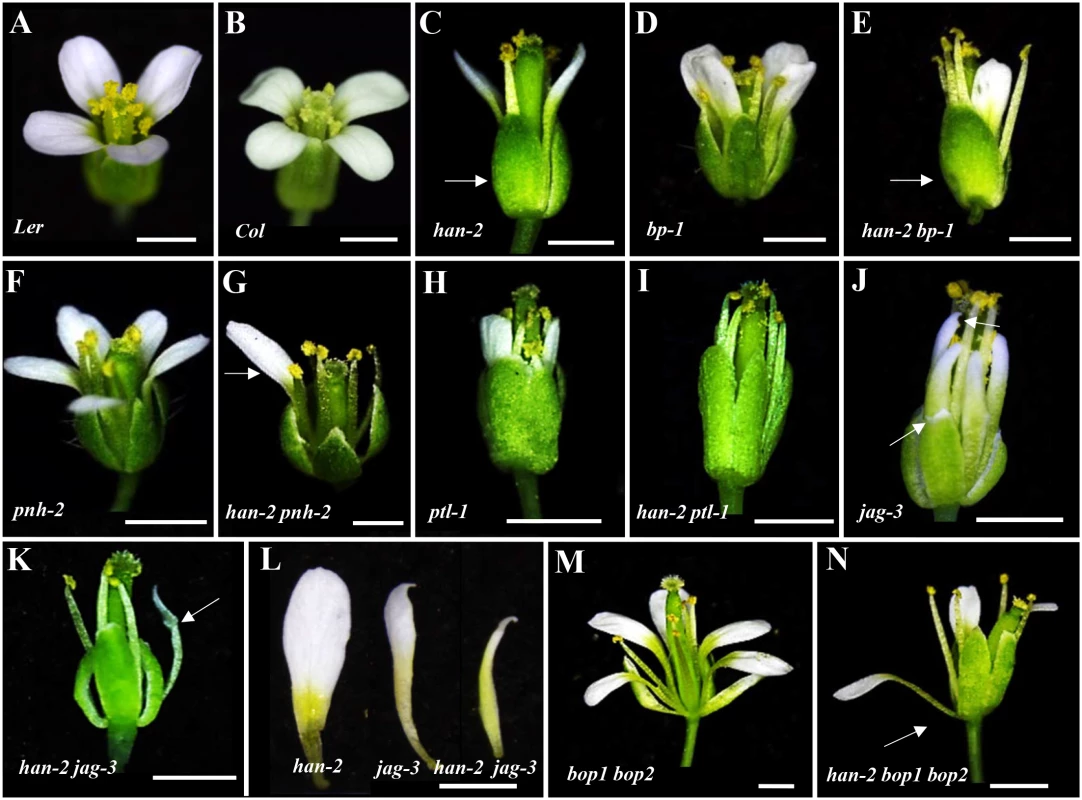

A and a represents P-value ≦ 0.05 and P-value ≦ 0.01 as compared to that in han-2, respectively. Fig. 1. Genetic interactions of HAN with meristem and primordia regulators during flower development.

(A-B) A Landsberg erecta flower (A) and a Columbia flower (B). (C) Representative image of han-2 single mutant with fused sepals (arrow) and reduced petals and stamens. (D-E) flowers in bp-1 (D) and han-2 bp-1 double mutant (E) with fused sepals (arrow) and reduced petals. (F-G) Floral phenotypes of pnh-2 mutant (F) and han-2 pnh-2 double mutant (G) showed a significantly reduced number of petals (arrow). (H-I) Representative flowers of ptl-1 (Col) (H) and han-2 ptl-1 double mutants (I) with loss of petals. (J) Images of jag-3 flower with serrate sepals and petals (arrows). (K) han-2 jag-3 with reduced number of petals. (L) The petals were narrower in the jag-3 han-2 double mutant. (M, N) Floral phenotypes of bop1 bop2 (M) and han-2 bop1 bop2 triple mutant (N) showed that petal number was rescued. Arrow in (N) indicates a petal in the first whorl. Bars = 1mm. Fig. 2. Scanning electron micrographs of the inflorescence meristems and flowers.

(A-F) Inflorescence meristems of wild-type Ler (A), han-2 (B), bp-1 (C), han-2 bp-1 (D), pnh-2 (E), han-2 pnh-2 (F) in 40-day-old plants. (G-L) Flowers of wild-type Ler (G), han-2 (H), bp-1 (I), han-2 bp-1 (J), pnh-2 (K), han-2 pnh-2 (L). (M) Statistical analyses of inflorescence meristems size from wild-type Ler, han-2, bp-1, pnh-2, han-2 bp-1, han-2 pnh-2. The measuring method was showed in Fig 2A. Values are the means of 6–10 plants grown under the same condition. Asterisks and double asterisks indicate that the values in the mutants were significantly different from the wild type at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively (unpaired t test, P > 0.05). Note that the inflorescence meristem and floral meristem of han-2 pnh-2 is smaller and taller than the single mutant han-2 and pnh-2. Bars = 40 μm. Next, we examined the genetic interactions of HAN with the primordial - specific genes PTL, JAG and BOP1/2 during flower development. The single mutant ptl-1 displays defective flowers with reduced petal numbers and disrupted petal orientation (Fig 1H and S1J Fig) [11, 35], and introduction of han-2 into the ptl-1 mutant further decreased petal numbers (Fig 1I and S1H–S1K Fig), resulting in an average of 0.9±0.2 petals (n = 60) in each han-2 ptl-1 double mutant flower (Table 1). JAG is required for lateral organ morphology, and loss of function of JAG results in flowers with narrow floral organs, jagged organ margins and slightly reduced numbers of petals (Fig 1J and S1L Fig, Table 1) [37, 38]. Loss of function of both HAN and JAG genes led to reduced petal numbers (Fig 1K and S1L and S1M Fig). The average number of petals in a han-2 jag-3 double mutant was 1.8±0.2 (n = 40), a more severe phenotype than that in the han-2 single mutants (Table 1). Similarly, the sepals were more serrated and the petals were narrower in han-2 jag-3 than in a jag-3 single mutant (Fig 1L and S1M Fig), suggesting that HAN and JAG have a synergistic effect on regulation of petal number, and sepal and petal morphology. In the han-2 bop1 bop2 triple mutant, on the other hand, the number of petals was largely rescued to normal (3.6±0.1) compared to 5.2±0.1 in bop1 bop2 mutants (Fig 1M and 1N and S1N and S1O Fig, Table 1). However, there were two developmental phenotypes in the han-2 bop1 bop2 triple mutants similar to the phenotype of bop1 bop2 mutants: 1) petaloid tissue replacing the sepal (Fig 1M and 1N); and 2) floral organs never fall off due to lack of an abscission zone (S2A and S2B Fig). However, the ectopic leaf tissues on the petioles observed in bop1 bop2 double mutants were mostly rescued upon introduction of han-2 (S2C Fig).

Transcriptional communications between boundary, meristem and floral organs

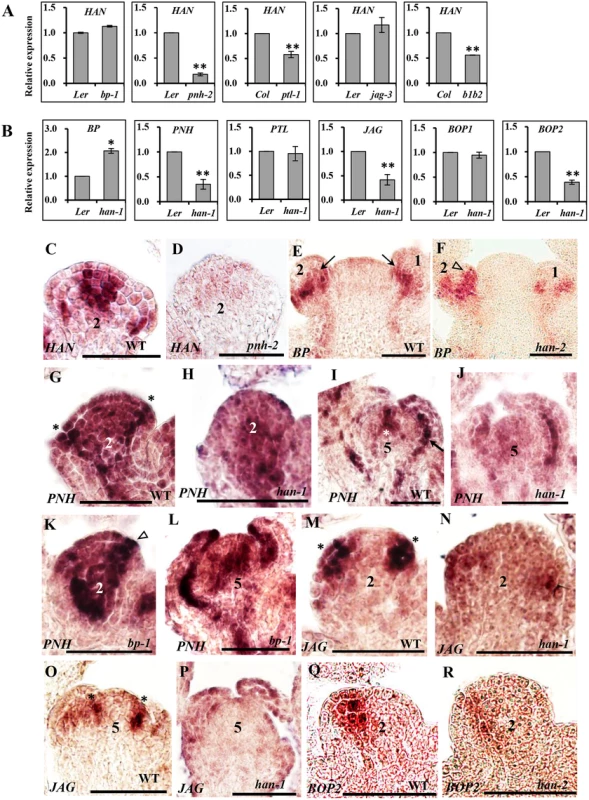

The mutant phenotypes suggested that HAN, together with BP, PNH, PTL, JAG and BOP1/2 regulates flower development via complex genetic interactions. To explore this potential regulatory network at the transcriptional level, gene expression was quantified by real time qRT-PCR in the mutant lines (Fig 3A and 3B and S3 Fig), and temporal and spatial expression patterns of these regulators were further analyzed by in situ hybridization (Fig 3C–3R and S4 Fig). HAN transcripts localize to the boundaries between the meristem and developing organ primordia, the junctional domain between the SAM and the stem, and the boundaries between different floral whorls [13]. qRT-PCR showed that the expression level of HAN was significantly reduced in the pnh-2, ptl-1 and bop1 bop2 mutant inflorescences, especially in the pnh-2 mutant, where transcript accumulation of HAN was decreased to 17% of the wild-type level, while there was no significant change in the jag-3 or bp-1 mutant plants (Fig 3A), suggesting that PNH, PTL and BOP1/2 promote HAN expression. Consistently, in situ hybridization showed that the HAN signal was dramatically decreased and diffused in the pnh-2 mutant (Fig 3C and 3D and S4A and S4B Fig). However, no obvious difference was detected for the signal of HAN in the bop1 bop2, ptl-1, jag-3 or bp-1 mutant as compared to that in wild-type (WT) (S4C–S4H Fig), probably due to such levels of reduction in the bop1 bop2 (-1.7 fold) and ptl-1(-1.8 fold) are visibly undetectable by in situ hybridization.

Fig. 3. Transcriptional analyses by quantitative real time RT-PCR and in situ hybridization in different mutant backgrounds.

(A-B) qRT-PCR analyses of HAN in the inflorescence of different mutant lines (A) and transcript levels of BP, PNH, PTL, JAG, BOP1 and BOP2 in the han-1 mutant (B). Arabidopsis ACTIN2 was used as an internal standard to normalize the templates. Three biological replicates were performed for each gene, and the bars represent the standard deviation. Asterisks and double asterisks indicate that expression levels in the mutants were significantly different from the wild type at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively. Lack of asterisk indicates the difference was not significant (unpaired t test, P > 0.05). (C-R) in situ hybridization. (C-D) HAN expression in wild-type (C) and pnh-2 (D) mutant flowers. (E-F) BP is expressed in the base of flower primordia (arrows) in wild-type (E), while BP signal appears to expand to include the initiating sepal primordia (triangle) in the han-2 mutant (F). (G-L) PNH expression in wild-type (G, I), han-1 (H, J) and bp-1 (K, L). In wild-type, PNH signal is detected in the floral meristem, the adaxial side of sepal primordia (asterisks in G), and the provascular tissue (arrow in I). In the han-1 mutant, PNH signal is greatly decreased (H, J), while in the bp-1 mutant, PNH expression is substantially increased (K, L). (M-P) JAG mRNA is located in developing organ primordia (asterisks) (M, O), and is reduced in the han-1 mutant (N, P); (Q-R) RNA localization of BOP2 in wild-type (Q) and han-2 mutant (R). In wild-type, BOP2 is predominantly expressed in the boundary between FM and sepal primordia at stage 2, and the expression of BOP2 is decreased in han-2 mutant plants (R). Seven biological samples were used for each probe. Numbers over each section represent the stage of floral development [1, 70]. The same probe concentration was used in the mutant and wild-type inflorescences and the slides were developed for the same period of time. Bars = 50μm. The meristem regulator BP is expressed in the cortex of developing pedicels within the base of floral primordia in WT plants (arrows in Fig 3E). In the han-2 mutant, BP signal appeared to expand into the initiating sepal primordia (triangle in Fig 3F), or expand to the abaxial of the sepal primordia in stage 5 (S4I and S4J Fig). qRT-PCR verified that the expression of BP was upregulated 2-fold in the han-1 inflorescence (Fig 3B), suggesting that the boundary gene HAN may inhibit the expression of BP from expanding into organ primordia. As for the other meristem regulator PNH, qRT-PCR showed that PNH transcription was reduced nearly 3-fold in han-1, but increased 4-fold in bp-1 (Fig 3B and S3B Fig). Consistently, the mRNA signal of PNH was concentrated in the adaxial side of sepal primordia (asterisk in Fig 3G), the floral meristem (FM) (Fig 3G and asterisk in Fig 3I), and the provascular tissue (arrow in Fig 3I) [28]. In the han-1 mutant, PNH signal was decreased, especially at the adaxial side of sepal primordia at stage 2 (Fig 3H), and the center of FM at stage 5 (Fig 3J). In the bp-1 mutant, PNH signal was greatly enhanced (Fig 3K and 3L), supporting the conclusion that HAN promotes while BP inhibits PNH expression during flower development. Therefore, the boundary-expressing HAN and the two meristem regulators PNH and BP form a regulatory feedback loop, in which HAN promotes PNH and represses BP transcription, and BP represses PNH while PNH acts positively on HAN expression.

The organ primordia-expressed gene PTL appears to be unaffected in the han mutant as detected by qRT-PCR (Fig 3B) and in situ hybridization (S4K and S4L Fig), and it is expressed in the margins of developing sepals and in the boundary between sepals and sepal primordia as previously reported (S4K and S4L Fig) [11]. In the five tested mutant lines (han-1, bp-1, pnh-2, ptl-1 and bop1 bop2), JAG expression was significantly downregulated, with the lowest expression in bp-1 (Fig 3B and S3D Fig), implying that JAG may be a downstream gene in the regulatory network. Consistently, about 25% of the han-1 mutant flowers almost abolished the JAG signal as compared to the enriched mRNA level in the emerging sepal primordia and stamen primordia in WT flowers (asterisks in Fig 3M–3P) [38], supporting the idea that HAN can stimulate JAG expression in organ primordia. Previous studies showed that BOP1 and BOP2 function redundantly and exhibit similar expression patterns [41, 46]. We found the expression of BOP1 displayed slight changes in all five mutant lines (han-1, bp-1, pnh-2, ptl-1 and jag-3) (Fig 3B and S3E Fig), while the expression of BOP2 was significantly repressed in the han-1 or jag-3 mutant, and significantly enhanced in the bp-1 mutant (Fig 3B and S3F Fig). Both BOP1 and BOP2 were expressed at the boundary between FM and sepal primordia, and base of sepals and other floral organs as previously reported (Fig 3Q and 3R and S4M–S4P Fig) [41, 47]. In han mutant flowers, the BOP2 signal appeared low (Fig 3R and S4P Fig), but the BOP1 signal remained unchanged (S4M and S4N Fig), suggesting that transcription of BOP1 and BOP2 may be under different regulatory control during flower development.

Protein interactions between HAN, PNH, BP and JAG

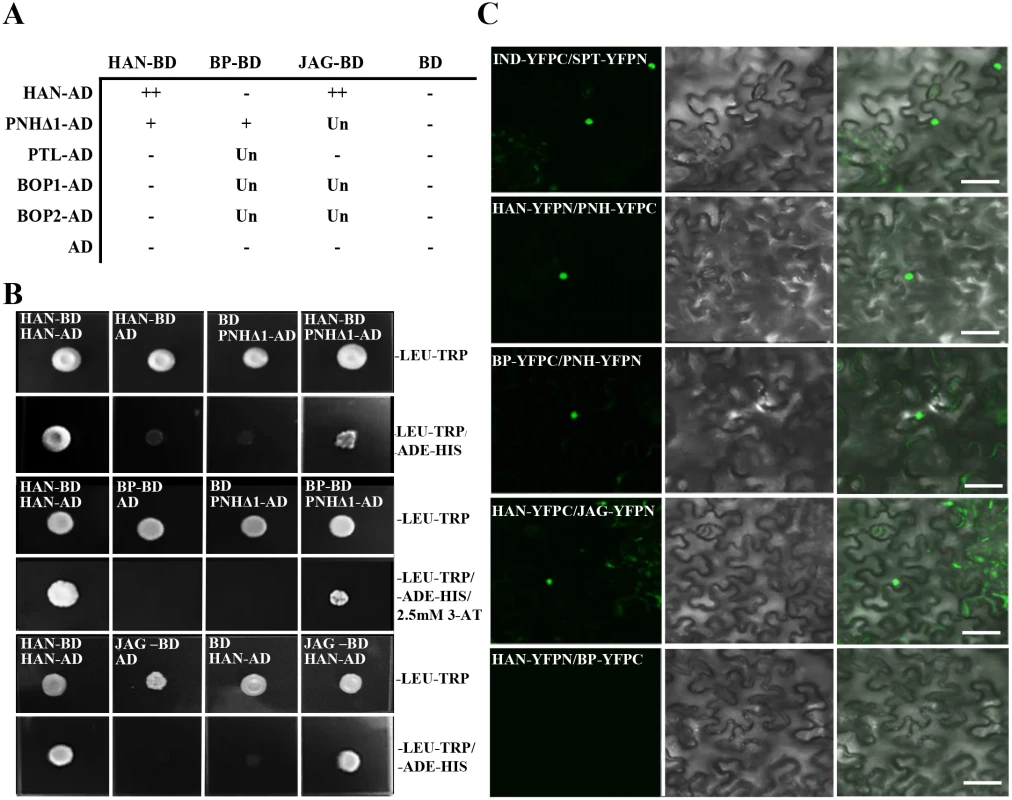

Based on the genetic and transcriptional data, yeast two-hybrid assays were used to investigate possible protein interactions between HAN with the two meristem regulators (BP and PNH) and three primordia-expressed regulators (PTL, JAG, BOP1/2) (Fig 4A). Considering the possible toxicity of full length PNH to the yeast cells, a series of deletion constructs of PNH was generated to test its interaction with other proteins (Fig 4B and S5 Fig). The PNH protein can be divided into three regions: the N-terminus (part I), the PAZ domain (part II) and the MID and KIWI domains (part III) (S5A Fig) [48]. Among all the deletion constructs of PNH, the construct (PNHΔ1) without the MID and KIWI domains had the strongest interaction with HAN and BP (Fig 4B and S5B Fig). However, HAN showed no physical interactions with BP directly (S5B Fig), suggesting that HAN communicates with the meristem through effects on PNH, and PNH interacts with BP. In addition, yeast cells co-expressing full length HAN and JAG can grow on selective medium, indicating that HAN physically interacts with JAG (Fig 4B), but there is no interaction observed between HAN and PTL, HAN and BOP1/2, no interactions detected between JAG and PTL (Fig 4A and S5B Fig).

Fig. 4. Protein interaction as detected by yeast two hybrid and bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC).

(A-B) Yeast two-hybrid assays. Summary of interactions performed (A).–indicates no interaction; + indicates positive interaction; ++ indicates strong interaction; Un indicates unknown. JAG-BD represents JAG fused with the GAL4 DNA binding domain (BD). HAN-AD indicates HAN fused with the GAL4 activation domain (AD). Similar labels were used for the other constructs. Mating with empty vector pGBKT7 or pGADT7 was used as a negative control. The positive control was the combination of HAN-BD and HAN-AD [49]. Yeast two-hybrid assays showed interactions between HAN and JAG, HAN and PNH, PNH and BP (B). Clones grown on medium lacking LEU-TRP indicated expression from both plasmids, and clones grown on selection medium lacking LEU-TRP and ADE-HIS suggested physical interactions between prey and bait proteins. 2.5mM 3-AT was used for inhibiting self-activation. (C) BiFC experiments show that HAN interacts with JAG and PNH, and PNH interacts with BP. Genes fused with the N-terminal or C-terminal fragment of YFP (YFPN or YFPC) were co-introduced into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. INDEHISCENT (IND)-YFPC and SPATULA (SPT)-YFPN were used as a positive control [71]. A positive interaction is shown by the YFP fluorescence (green) in nuclei (left panel), differential interference contrast (DIC) of the tobacco cells is shown in the middle panel, and the two merged channels are shown in the right panel. The label IND-YFPC represents IND fused with C-terminus half of YFP in frame, and similarly for other constructs. Bars = 50μm. To verify the interactions between HAN, BP, PNH and JAG in planta, bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays were performed in the abaxial side of tobacco leaves. The results indicated interaction of HAN with PNH, HAN with JAG, and PNH with BP, confirming that HAN physically interacts with the meristem regulator PNH and primordial regulator JAG, and PNH interacts with the other meristem regulator BP in the nucleus (Fig 4C). Consistently, the BiFC assay showed no interaction between HAN and BP, or HAN and BOP1/2 in planta (Fig 4C and S6 Fig).

HAN may maintain boundary function via modulation of hormone action

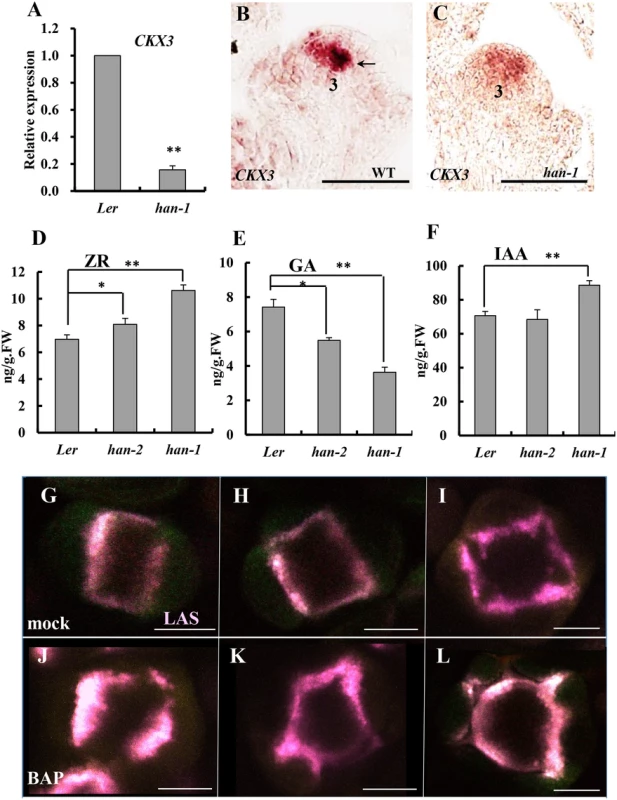

Our previous research by time-course microarray indicated that transient induction of HAN by dexamethasone (DEX) treatment in the p35S:HAN-GR line led to downregulation of HAN through autoregulation, and specifically repressing a cytokinin degradation gene CYTOKININ OXIDASE 3 (CKX3) among the CKX family [49]. To further characterize the regulation of CKX3 by HAN, we examined the expression level of CKX3 in the han-1 null allele by qRT-PCR as well as by in situ hybridization (Fig 5A–5C). CKX3 mRNA abundance was reduced more than 6-fold in the han-1 inflorescence (Fig 5A). In situ hybridization showed that CKX3 mRNA is located in the center of the FM and in the boundary between the long stamen primordia and the gynoecial primordium in WT flowers, as previously reported (Fig 5B) [50]. In the han-1 mutant, CKX3 signal was decreased and diffused, appearing throughout the FM (Fig 5C). Given that the expression domain of HAN and CKX3 are overlapping (Figs 3C, 5B, S4E and S4G) [13], and that transient overexpression of HAN mimics loss of HAN function through self-repression [49], HAN may function through stimulating the expression of CKX3 to maintain a low cytokinin level and thus reduced cell division in the boundary. Next, the content of the cytokinin trans-zeatin riboside (ZR) in the inflorescence was measured. As expected, the ZR levels increased in homozygotes for the han-2 weak allele and were even higher in han-1 null mutants as compared to WT (Fig 5D). We also measured the levels of gibberellins (GA) and auxin (IAA) in the han mutant inflorescence and found a significant decrease in the GA content and a small increase in the IAA level (Fig 5E and 5F).

Fig. 5. Boundary function links with phytohormone action in the inflorescence.

(A) Real-time qRT-PCR analysis of RNA from the cytokinin degradation gene CKX3 showed a substantial decrease in a han-1 mutant background. (B-C) in situ hybridization indicated that CKX3 signal is detected in the center of the floral meristem and the boundary between long stamen primordia and gynoecial primordia (black arrow) at stage 3 in a wild-type flower (B), but CKX3 expression was reduced in level and appeared to be diffused throughout the floral meristem in the han-1 mutant (C); (D-F) The content of trans-zeatin riboside (ZR) (D), gibberellins (GA) (E) and auxin (IAA) (F) in the inflorescence of Ler, weak allele han-2 and null allele han-1 plants. Three biological replicates were performed and the bars represent standard deviation. Asterisks and double asterisks represent significant difference as compared to that in the wild-type (Ler) at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively. Lack of asterisk indicates no significant difference (unpaired t test, P > 0.05). (G-L) Cytokinin treatment of plants harboring pLAS::LAS-GFP (purple), normal meristem-to-sepal boundary was formed in the mock-treated plants (G-I), but the boundaries display improper placement, enlarged domains as well as increased number after three days of 50μM N6-benzylaminopurine treatment (J-L). Images are representative of 20 samples. Numbers over each section represent the stage of floral development [1, 70]. Bars = 50μm. To test whether cytokinin regulates boundary function, plants were treated with 50μM N6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) for three days, and boundary formation was observed every 24 hours by following expression of the boundary-specific reporter pLAS::LAS-GFP [51]. 50μM BAP treatment resulted in enlargement of the SAM and increased numbers of floral organs as previously reported [52]. As compared to mock-treated plants (Fig 5G–5I), meristem-to-sepal boundaries (marked by pLAS::LAS-GFP in purple) displayed improper placement, enlarged domains, and increased numbers of boundaries, which preceded and predicted the increased numbers of sepals (Fig 5J–5L). For example, as shown in Fig 5K, the formation of five boundaries predicts the development of five sepals with unequal sizes, which is often the case in cytokinin-treated lines [52].

HAN directly binds to the CKX3, JAG and BOP1/2

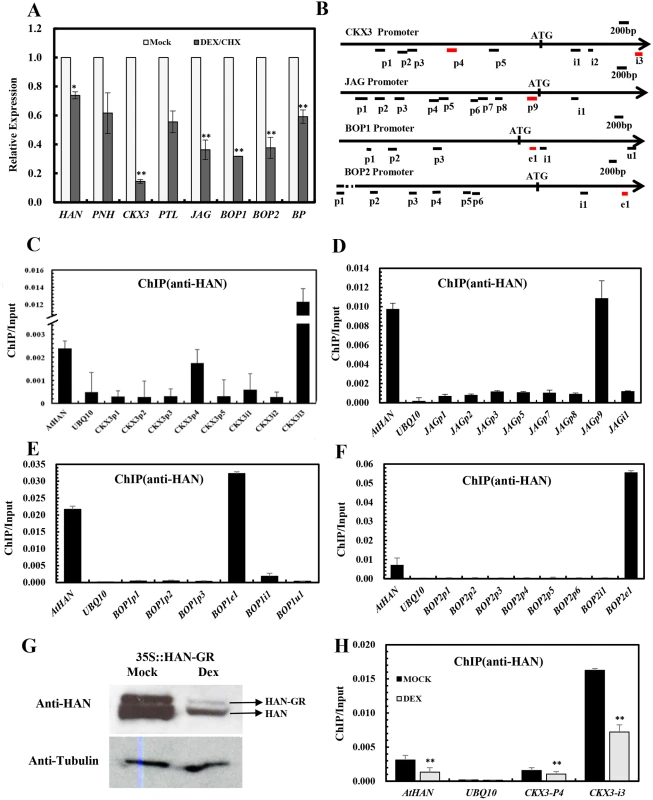

To explore whether HAN directly regulates the transcription of BP, PNH, PTL, JAG, BOP1/ 2 and CKX3, qRT-PCR was performed in the inflorescence after 4h treated with DEX and cycloheximide in 35S:HAN-GR plants. As shown in Fig 6A, the expression of CKX3, JAG, BOP1, BOP2 and BP was significantly reduced compared to the mock-treated plants [49]. Thus, a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP) was performed, followed by quantitative PCR analysis (ChIP-PCR), with anti-HAN antibodies, to verify the direct bindings. The specificity of anti-HAN antibodies has been previously tested [49]. The various amplicons used for the ChIP-PCR assay are shown in Fig 6B, which contained the enriched regions of DNA sequences WGATAR (W = A or T and R = A or G) in the promoters and genic regions of CKX3, JAG, BOP1, BOP2 or BP. The promoter region −977 to −735 bp of HAN was used as a positive control and an amplicon derived from the UBQ10 promoter was used as a negative control [49]. Amplicons CKX3p4 and CKX3i3 were significantly enriched when normalized to the negative control (Fig 6C). CKX3p4 spans the promoter region from -1677 to -1511 bp of CKX3, with the recognition motif WGATAR at -1619 ~ -1614bp. CKX3i3 locates in the first intron region from 1539 to 1693 bp of CKX3, with the recognition motif at 1569~1574 bp and the ChIP/Input ratio increased over 5-fold compared to the positive control HAN (Fig 6C). Similarly, amplicon JAGp9, which spans the promoter region from -282 to -96 bp of JAG, with two recognition motifs at -175~ -170 bp and -166 ~ -161 bp, respectively, was significantly enriched (Fig 6D). BOP1e1 and BOP2e1, which span the first exon from 330 to 476 bp of BOP1 (recognition motif at 363~368 bp), and the second exon region from 1862 to 2012 bp of BOP2 (recognition motif at 1939~1944bp), respectively, were also significantly enriched, with the ChIP/Input ratio increased 1.5 and 7.7 fold, respectively, as compared to the positive control HAN (Fig 6E and 6F). By contrast, all of the other tested amplicons from CKX3, JAG or BOP1/2 were not enriched compared to the UBQ10 amplicon, suggesting that the ChIP-PCR assay was amplicon-specific. Further, no amplicons in the promoters and genic regions of BP, PNH and PTL were found to be significantly enriched (S7 Fig), indicating that HAN did not directly bind to BP, PNH and PTL.

Fig. 6. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses indicate that HAN directly binds to CKX3, JAG and BOP1/2.

(A) Transcription analyses by qRT-PCR in the p35S:HAN-GR inflorescences treated with dexamethasone (DEX) and cycloheximide (CHX) for 4h. Arabidopsis ACTIN2 was used as an internal control to normalize the expression. Three biological replicates were performed for each gene, and the bars represent the standard deviation. Asterisks and double asterisks represent significant difference as compared to that in the wild-type (Ler) at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively (unpaired t test). (B) Schematic diagram of the amplicons located in the CKX3, JAG, BOP1 and BOP2 genomic sequence used for ChIP analysis. Letter p represents promoter, i represents intron, e indicates exon, u represents UTR. (C-G) ChIP PCR assay with anti-HAN antibody showed the enrichment of amplicons from CKX3 (C), JAG (D), BOP1 (E) and BOP2 (F) from wild-type Ler inflorescence. (G) Western blot analyses in the p35S::HAN-GR line showed reduced HAN protein level after induction of HAN by DEX treatment. (H) ChIP PCR assay of HAN and CKX3 in the p35S:HAN-GR inflorescences treated with DEX for 3 days. The data were the average of two biological replicates. HAN and UBQ10 were used for positive and negative controls, respectively. Double asterisks represent significant difference as compared to that in the mock-treated plants at P < 0.01 (unpaired t test). Given that the expression of CKX3, JAG and BOP2 were greatly reduced in both han-1 and DEX-treated 35S:HAN-GR plants, we verified the HAN autoregulation by western blotting and the binding of HAN and CKX3 using ChIP-PCR between the DEX - and mock-treated 35S:HAN-GR plants. Our data showed that HAN protein was greatly reduced in the 35S::HAN-GR line upon DEX treatment, supporting the self-regulation of HAN (Fig 6G). Consistently, binding on CKX3 and on HAN itself was significantly reduced upon DEX treatment (Fig 6H).

Discussion

HAN communicates with cells in the meristem through PNH, and with organ primordia via JAG and BOP2 to precisely orchestrate flower development

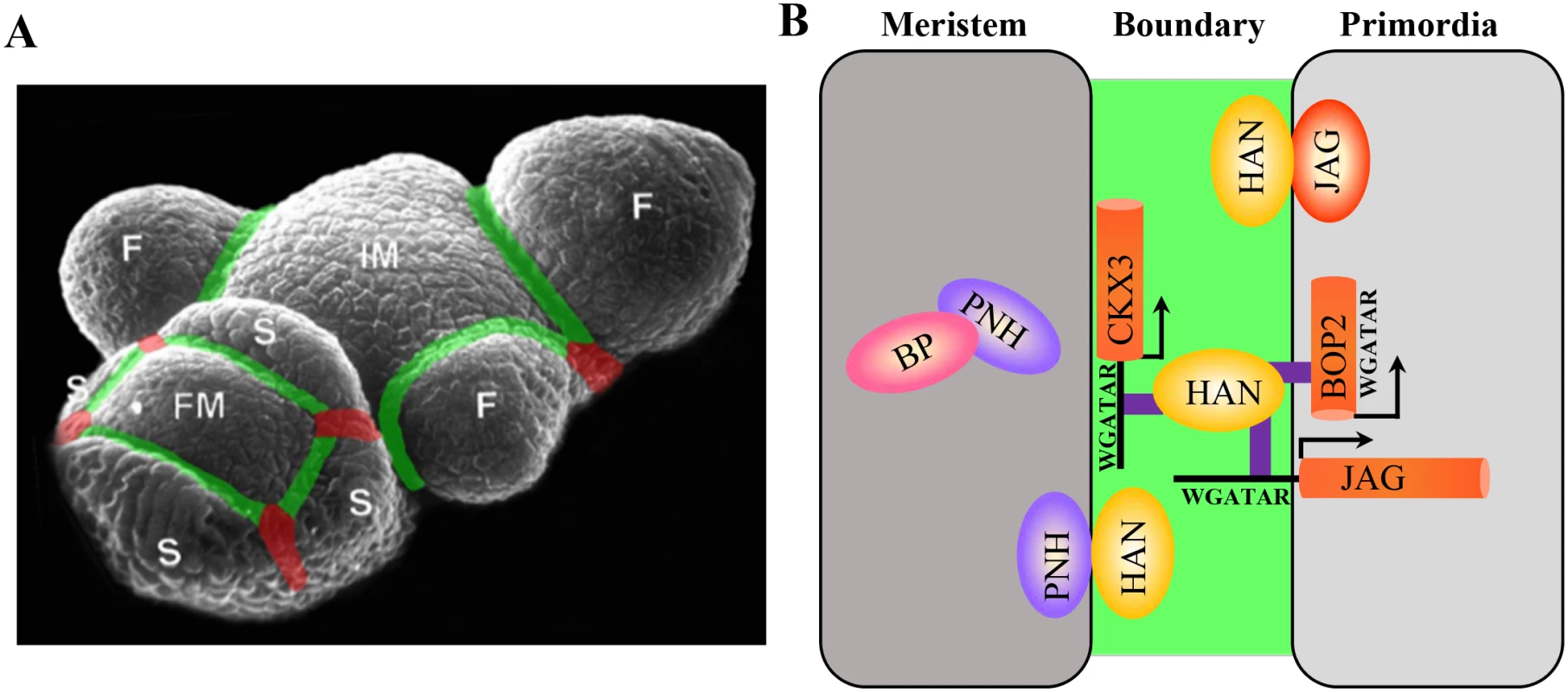

Proper boundary formation is required for meristem maintenance, organ separation, floral organ patterning, and axial meristem initiation [10, 11, 14, 16, 19, 20, 22, 53]. Previous studies have shown that boundary-expressing CUC genes induce the expression of the meristematic marker STM, while STM represses CUC expression in the meristem, forming a negative feedback loop during embryogenesis [9, 22]. Here we found that the boundary-expressing gene HAN interacts with meristem regulators PNH genetically, transcriptionally and biochemically. Double mutant han-2 pnh-2 displayed synergistic effect on petal reduction and meristem organization (Figs 1 and 2). At the transcriptional level, HAN and PNH promote each other, while HAN represses BP, and BP represses PNH (Fig 3). At the protein level, HAN interacts with PNH and PNH interacts with BP (Fig 4). Therefore, HAN may communicate with the meristem through a direct interaction with PNH and indirectly with BP to ensure proper meristem organization and flower development (Fig 7B). The expression of HAN and PNH overlap in the boundary regions and the bottom of the meristem in the stage 2 flowers (Fig 3C and 3G) [13], the interaction between HAN and PNH may occur in these overlapping regions to maintain proper meristem organization during continuous organogenesis (Fig 7B).

Fig. 7. Regulatory interactions between boundary, meristem and floral organ primordia in Arabidopsis.

(A) Schematic boundaries in the Arabidopsis inflorescence. The M–O boundaries were marked in green, and the O–O boundaries were marked in red. IM, inflorescence meristem; F, floral primordia; FM, floral meristem; S, sepal primordia. (B) Working model of boundary gene HAN serving as a link between the meristem and floral primordia to separate distinct cell identity during flower development. The boundary communicates with meristem through a HAN-PNH interaction, and PNH interacts with BP in the meristem to maintain meristem organization during continuous organogenesis. On the other hand, HAN physically interacts with JAG protein and directly binds to the promoter of JAG and genic region of BOP2 to promote floral organ development. In addition, HAN directly activates CKX3 to reduce cytokinin content, thus suppressing cell division in the boundary and serving as a bridge between meristem and organ primordia. On the other side, the boundary gene HAN communicates with floral organ primordia through JAG and BOP2. Genetically, HAN coordinatively regulates flower organ development with JAG and BOP1/2 (Fig 1 and S1 Fig). qRT-PCR analysis and in situ hybridization showed that HAN promotes the expression of JAG and BOP2 in the organ primordia (Fig 3). Biochemical analysis showed that HAN physically interacts with JAG (Fig 4), and a ChIP-PCR assay indicated that HAN directly binds to the promoter of JAG and exon of BOP2 (Fig 6). Therefore, HAN directly stimulate the transcription of JAG and BOP2, and interact with JAG at the protein level (Fig 7B). Given that transcripts of HAN, JAG and BOP2 overlap in the boundary regions in the stage 2 flower (Fig 3C, 3M and 3Q), HAN may directly stimulate the transcription of JAG and BOP2 in the boundary region to promote organ primordia development. Consistent with this notion, the serrated sepals in the jag mutant were also observed in a han-1 mutant, which could be due to reduced JAG expression, or to elimination of its protein partner, in the han-1 mutant [38]. Previous finding showed that JAG can directly bind to the promoter of BOP2 [54]. Our data showed that BOP2 was significantly reduced in the jag-3 mutant, indicating that JAG directly stimulates the transcription of BOP2 in the inflorescence. Given that HAN directly binds to the exon of BOP2, HAN promotes the expression of BOP2 directly or indirectly through JAG. Despite HAN also directly binds to the exon of BOP1 (Fig 6E), transcription of BOP1 was not changed in the han-1 mutant, suggesting that additional factors may antagonize the effect of HAN on BOP1. In the bop1 bop2 mutant, JAG expression in the inflorescence is down-regulated, in contrast to the upregulation of JAG expression in leaves or in the vegetative shoot apex [40], indicating that different interaction modules of JAG and BOP1/2 exist during leaf and flower development.

Previous data showed that JAG directly binds to the promoter of PTL to control petal growth and shape [55], and we found that JAG repressed the expression of PTL (S3C Fig). Thus, the role of HAN in control of petal number and petal morphology as revealed by the double mutant analysis (Fig 1) can be explained by the direct interaction with JAG and BOP2 in the petal boundaries, and thus indirect interaction with PTL during flower development in Arabidopsis. Notably, ChIP-Seq showed that JAG directly targets HAN as well [54]. However, the expression of HAN showed no significant change in the jag-3 mutant (Fig 3A), probably due to autoregulation of HAN [49].

CKX3 and GNC/GNL may act as the direct linkage between HAN and hormone actions

Our qRT-PCR, in situ hybridization and ChIP-PCR data showed that HAN directly binds to the cytokinin degradation gene CKX3 and promotes CKX3 expression (Figs 5 and 6). In the han-1 mutant, the CKX3 signal intensity was reduced and diffused throughout the FM (Fig 5C), resulting in elevated cytokinin content (Fig 5D). Exogenous cytokinin treatment disrupts boundary formation and results in increased floral organ numbers (Fig 5G–5L). Therefore, HAN may maintain the proper boundary function by directly activating CKX3, thus reducing cytokinin content and suppressing cell division in the boundary (Fig 7B). Han et al. [56] showed that pAP1::IPT8 (which encodes a rate-limiting enzyme in cytokinin biosynthesis) lines displayed loss of petals [56], while loss of function of both CKX3 and CKX5 results in a slight increase in the number of sepals and petals[50], rather than the reduced floral organ number observed in the han-1 mutant, suggesting that the distribution of cytokinin rather than the content of cytokinin in the flower is more essential for regulation of petal number, and that HAN regulates flower development via a complex interaction network, with the CKX3-mediated cytokinin pathway only as one branch.

In addition, the signal intensity of the auxin response marker DR5 was previously shown to be greatly reduced in the han-2 mutant [49], while the IAA level was up-regulated in the han mutant (Fig 5F), suggesting that HAN represses auxin biosynthesis and promotes auxin signaling in the inflorescence. Consistent with the antagonistic interaction between auxin and GA [57], the GA level was significantly decreased in the han mutant inflorescence (Fig 5E). Recently, HAN was shown to repress itself and three GATA3 family genes, HAN-LIKE 2 (HANL2), GATA, NITRATE-INDUCIBLE, CARBON-METABOLISM-INVOLVED (GNC), and GNC-LIKE (GNL) [49]. GNC and GNL are direct downstream targets of AUXIN RRESPONSE FACTOR2 (ARF2) that mediates auxin response, and GNC and GNL are also downstream targets of the GA signaling pathway involving DELLAs and PIFs in Arabidopsis [58]. Therefore, HAN may regulate flower development through the CKX3-mediated cytokinin homeostasis, auxin and GA biosynthesis, and GNC/GNL-mediated auxin and gibberellin responses.

Methods

Plant materials and genetics

The Arabidopsis thaliana Landsberg erecta (Ler) and Columbia (Col) ecotypes, the mutant alleles han-1 (Ler), han-2 (Ler), pnh-2 (Ler), jag-3 (Ler), bp-1 (Ler), han-2(Col) and ptl-1(Col) were described previously [11, 13, 26, 38, 59] and obtained from the Meyerowitz lab stock collection. The reporter line pLAS::LAS-GFP was kindly provided by Dr. Yuval Eshed [51]. The bop1-4 bop2-11 double mutant plants (Col) were kindly provided by Jennifer C. Fletcher. Double or triple mutant combinations with han-2 were generated by crossing using the same ecotype background, and identified by genotyping using the primers listed in S1 Table. For han-2 genotyping, a 852-bp fragment was amplified and digested by TseI, which recognizes the mutant site. For jag-3 genotyping, PCR products from the mutant were cleaved by TseI. For pnh-2 genotyping, a 111-bp product was amplified by PCR, and EcoRIcleaves only the wild-type product. For ptl-1 genotyping, a 726-bp fragment was amplified and digested by CfrI, which digests only the wild-type product. Genotypings for bop1-4 bop2-11 and bp-1 were performed as described previously [44]. Plants were grown in soil at 22°C under conditions of 16h light/8h dark.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from 3–5 inflorescence samples using RNaEXTM Total RNA Isolation Solution (Generay, China). cDNA was synthesized from 4μg total RNA using reverse transcriptase (Aidlab, China) and qRT-PCR analyses were performed on an ABI PRISM 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). Each qRT-PCR experiment was performed in three biological replicates and three technical replicates. The ACTIN2 gene was used as an internal reference to normalize the expression data. Fold change was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method [60] and the standard deviation was calculated between three biological replicates, using the average of the three technical replicates for each biological sample. The gene-specific primers are listed in S1 Table.

Endogenous hormone measurement

To examine auxin, cytokinin and gibberellin levels in the han-1 and han-2 mutant plants, about 0.1g of inflorescence (about 20–35 inflorescence) was harvested from han-1, han-2 or Ler plants grown under the same conditions and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen until further use. Sample extraction and hormone measurements were performed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays as previously reported [61]. Standard IAA, GA and trans-zeatin riboside (ZR) (Sigma, USA) was used for calibration.

in situ hybridization

Arabidopsis inflorescences were fixed in 3.7% formol-acetic-alcohol (FAA) (3.7% formaldehyde, 5% glacial acetic acid, and 50% ethanol) and stored at 4°C until use. Probe synthesis was performed on cDNA using gene-specific primers including SP6 and T7 RNA polymerase binding sites. Probes for HAN, PNH, BOP1/2, PTL, and CKX3 were made using the same sequences as previously reported [13, 40, 44, 50, 59, 62], and probes for JAG and BP were synthesized with the specific coding sequence fragments as templates. Sample fixation, sectioning and in situ hybridization was performed as previously described [49]. The primers for probe synthesis are listed in S1 Table.

DEX and cytokinin treatments

Transient overexpression of HAN was achieved through 10μM DEX treatment on p35S::HAN-GR inflorescence apices. 10μM cycloheximide was used with 10μM DEX for 4h treatment. DEX solution was applied by pipette every 24h. Cytokinin treatment was performed using 50μm N6-benzylaminopurine, and applied by pipette every 24h. Each treatment was repeated at least three times with corresponding mock-treated controls.

Live imaging

Plants were grown and inflorescence meristems were prepared for live imaging as previously described [6]. All imaging was done using a Zeiss 510 Meta laser scanning confocal microscope with a 40x water dipping objective using the Z-stacks mode. For the pLAS::LAS-GFP reporter line, 20 samples were imaged to confirm the observed patterns were representative, and similar sets of lasers and filters were used to image the reporter as previously described [6, 63].

Yeast two hybrid assay

Full-length coding sequences for HAN, JAG, PNH, BP, IND, SPT, PTL, BOP1, BOP2 or a series of truncated PNH fragments were cloned into pGBKT7 (bait vector) or pGADT7 (prey vector). All constructs were confirmed by sequencing before transformation into yeast strain AH109. The bait and prey vectors were transformed according to the manufacturer’s instructions of MatchmakerTM GAL4 Two-Hybrid System 3 & Libraries (Clontech). Protein interactions were assayed on selective medium lacking Leu, Trp, His and Ade or supplemented with 2.5 mM 3-Amino-1, 2, 4-triazole (3-AT). The gene primers used for yeast two hybrid experiments are listed in S1 Table.

Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) assay

Full-length coding sequences for HAN, JAG, PNH, BP, IND, SPT, BOP1 and BOP2 (without stop codons) were amplified by PCR using gene-specific primers, and cloned into the vectors pSPYNE-35S or pSPYCE-35S containing each half of YFP (N - or C - terminus) to generate the fusion proteins (such as HAN-YFP N-terminus) in frame as previously described [64]. All constructs were verified by sequencing before transformation into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. The two plasmids for testing specific interaction were co-transformed into the abaxial sides of 4-7-week old Nicotiana benthamiana leaves as previously described [65]. After 48h co-infiltration, the tobacco leaves were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal laser scanning microscope. YFP signals and DIC of tobacco cells were taken at the same time from different detection channels. The gene primers used for BiFC are listed in S1 Table.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP-PCR was performed as described by Gendrel et al. [66] with slight modifications. Briefly, about 2g of inflorescence tissue from wild-type Ler or DEX-treated p35S::HAN-GR line for three days were harvested and fixed in 37ml 1% formaldehyde and cross-linked for 15 min with vacuum infiltration at room temperature, followed by addition of glycine with vacuum infiltration for 5 min to terminate the cross-linking reaction. Nuclei were isolated and lysed, and chromatin was sonicated to an average size of 500 bp. The sonicated chromatin served as input and stored at -20°C until use. Immunoprecipitation reactions were performed using anti-HAN antibody [49] and no antibody as a negative control. The complex of chromatin-antibody was captured with protein G agarose beads (Millipore) followed by precipitated DNA purification and elution, and DNA deposited with glycogen carrier (Thermo) served as a template for qRT-PCR. The enrichment regions of DNA sequences WGATAR (W = A or T and R = A or G) in the promoters or genic regions were chosen to perform qRT-PCR [67–69]. Two biological repeats and three technical replicates were performed for each gene. HAN and UBQ10 were used for positive and negative controls, respectively [49]. The ChIP/Input ratio was calculated by the equation 2(Ct(MOCK)-Ct(HAN-ChIP))/2(Ct(MOCK)-Ct(INPUT)). The primer pairs used in ChIP-PCR were listed in S1 Table.

Scanning electron microscopy

Inflorescence of Ler, han-2, bp-1, han-2 bp-1, pnh-2, han-2 pnh-2 from 40-day-old plants, and stage 7–9 fruit samples of han-2, bop1bop2 and han-2bop1bop2 were prepared for SEM. After removing the flowers or floral organs, samples were fixed in FAA overnight. The samples were then critical-point dried in liquid CO2, sputter coated with gold and palladium for 60s, and examined at an acceleration voltage of 2kV using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi Model S-4700, Japan).

Western blotting assay

Inflorescence tissues from mock or DEX-treated p35S::HAN-GR line for three days were harvested in liquid nitrogen. The plant total protein extraction kit (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for protein extraction. Western blotting was performed as previously described [49].

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative or GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: HAN (AT3G50870), PNH (AT5G43810), BOP1 (AT3G57130), BOP2 (AT2G41370), JAG (AT1G68480), PTL (AT5G03680), KNAT1/BP (AT4G08150), CKX3 (AT5G56970), IND (AT4G00120), SPT (AT4G36930).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Alvarez-Buylla ER, Benitez M, Corvera-Poire A, Chaos CA, de Folter S, Gamboa DBA, et al. Flower development. Arabidopsis Book. 2010;8:e0127. doi: 10.1199/tab.0127 22303253.

2. Aida M, Tasaka M. Genetic control of shoot organ boundaries. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9(1):72–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.11.011 16337829.

3. Breuil-Broyer S, Morel P, de Almeida-Engler J, Coustham V, Negrutiu I, Trehin C. High-resolution boundary analysis during Arabidopsis thaliana flower development. Plant J. 2004;38(1):182–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02026.x 15053771.

4. Kwiatkowska D. Surface growth at the reproductive shoot apex of Arabidopsis thaliana pin-formed 1 and wild type. J Exp Bot. 2004;55(399):1021–32. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh109 15020634.

5. Laufs P, Peaucelle A, Morin H, Traas J. MicroRNA regulation of the CUC genes is required for boundary size control in Arabidopsis meristems. Development. 2004;131(17):4311–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.01320 15294871.

6. Heisler MG, Ohno C, Das P, Sieber P, Reddy GV, Long JA, et al. Patterns of auxin transport and gene expression during primordium development revealed by live imaging of the Arabidopsis inflorescence meristem. Curr Biol. 2005;15(21):1899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.052 16271866.

7. Aida M, Tasaka M. Morphogenesis and patterning at the organ boundaries in the higher plant shoot apex. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;60(6):915–28. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2760-7 16724261.

8. Sakai H, Medrano LJ, Meyerowitz EM. Role of SUPERMAN in maintaining Arabidopsis floral whorl boundaries. Nature. 1995;378(6553):199–203. doi: 10.1038/378199a0 7477325.

9. Aida M, Ishida T, Tasaka M. Shoot apical meristem and cotyledon formation during Arabidopsis embryogenesis: interaction among the CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON and SHOOT MERISTEMLESS genes. Development. 1999;126(8):1563–70. 10079219.

10. Greb T, Clarenz O, Schafer E, Muller D, Herrero R, Schmitz G, et al. Molecular analysis of the LATERAL SUPPRESSOR gene in Arabidopsis reveals a conserved control mechanism for axillary meristem formation. Genes Dev. 2003;17(9):1175–87. doi: 10.1101/gad.260703 12730136.

11. Brewer PB, Howles PA, Dorian K, Griffith ME, Ishida T, Kaplan-Levy RN, et al. PETAL LOSS, a trihelix transcription factor gene, regulates perianth architecture in the Arabidopsis flower. Development. 2004;131(16):4035–45. doi: 10.1242/dev.01279 15269176.

12. Takeda S, Matsumoto N, Okada K. RABBIT EARS, encoding a SUPERMAN-like zinc finger protein, regulates petal development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2004;131(2):425–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.00938 14681191.

13. Zhao Y, Medrano L, Ohashi K, Fletcher JC, Yu H, Sakai H, et al. HANABA TARANU is a GATA transcription factor that regulates shoot apical meristem and flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16(10):2586–600. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.024869 15367721.

14. Hibara K, Karim MR, Takada S, Taoka K, Furutani M, Aida M, et al. Arabidopsis CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON3 regulates postembryonic shoot meristem and organ boundary formation. Plant Cell. 2006;18(11):2946–57. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.045716 17122068.

15. Keller T, Abbott J, Moritz T, Doerner P. Arabidopsis REGULATOR OF AXILLARY MERISTEMS1 controls a leaf axil stem cell niche and modulates vegetative development. Plant Cell. 2006;18(3):598–611. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038588 16473968.

16. Borghi L, Bureau M, Simon R. Arabidopsis JAGGED LATERAL ORGANS is expressed in boundaries and coordinates KNOX and PIN activity. Plant Cell. 2007;19(6):1795–808. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047159 17557810.

17. Ha CM, Jun JH, Nam HG, Fletcher JC. BLADE-ON-PETIOLE1 and 2 control Arabidopsis lateral organ fate through regulation of LOB domain and adaxial-abaxial polarity genes. PLANT CELL. 2007;19(6):1809–25. 17601823

18. Husbands A, Bell EM, Shuai B, Smith HM, Springer PS. LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES defines a new family of DNA-binding transcription factors and can interact with specific bHLH proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(19):6663–71. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm775 17913740.

19. Peaucelle A, Morin H, Traas J, Laufs P. Plants expressing a miR164-resistant CUC2 gene reveal the importance of post-meristematic maintenance of phyllotaxy in Arabidopsis. Development. 2007;134(6):1045–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.02774 17251269.

20. Raman S, Greb T, Peaucelle A, Blein T, Laufs P, Theres K. Interplay of miR164, CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON genes and LATERAL SUPPRESSOR controls axillary meristem formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2008;55(1):65–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03483.x 18346190.

21. Lee DK, Geisler M, Springer PS. LATERAL ORGAN FUSION1 and LATERAL ORGAN FUSION2 function in lateral organ separation and axillary meristem formation in Arabidopsis. Development. 2009;136(14):2423–32. doi: 10.1242/dev.031971 19542355.

22. Takada S, Hibara K, Ishida T, Tasaka M. The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1 gene of Arabidopsis regulates shoot apical meristem formation. Development. 2001;128(7):1127–35. 11245578.

23. Byrne ME, Barley R, Curtis M, Arroyo JM, Dunham M, Hudson A, et al. Asymmetric leaves1 mediates leaf patterning and stem cell function in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2000;408(6815):967–71. doi: 10.1038/35050091 11140682.

24. Byrne ME, Simorowski J, Martienssen RA. ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 reveals knox gene redundancy in Arabidopsis. Development. 2002;129(8):1957–65. 11934861.

25. Hibara K, Takada S, Tasaka M. CUC1 gene activates the expression of SAM-related genes to induce adventitious shoot formation. Plant J. 2003;36(5):687–96. 14617069.

26. Venglat SP, Dumonceaux T, Rozwadowski K, Parnell L, Babic V, Keller W, et al. The homeobox gene BREVIPEDICELLUS is a key regulator of inflorescence architecture in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(7):4730–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072626099 11917137.

27. Smith HM, Hake S. The interaction of two homeobox genes, BREVIPEDICELLUS and PENNYWISE, regulates internode patterning in the Arabidopsis inflorescence. Plant Cell. 2003;15(8):1717–27. 12897247.

28. Moussian B, Schoof H, Haecker A, Jurgens G, Laux T. Role of the ZWILLE gene in the regulation of central shoot meristem cell fate during Arabidopsis embryogenesis. EMBO J. 1998;17(6):1799–809. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1799 9501101.

29. Liu Q, Yao X, Pi L, Wang H, Cui X, Huang H. The ARGONAUTE10 gene modulates shoot apical meristem maintenance and establishment of leaf polarity by repressing miR165/166 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;58(1):27–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03757.x %/ (c) 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation (c) 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 19054365.

30. Ji L, Liu X, Yan J, Wang W, Yumul RE, Kim YJ, et al. ARGONAUTE10 and ARGONAUTE1 regulate the termination of floral stem cells through two microRNAs in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(3):e1001358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001358 21483759.

31. Zhu H, Hu F, Wang R, Zhou X, Sze SH, Liou LW, et al. Arabidopsis Argonaute10 specifically sequesters miR166/165 to regulate shoot apical meristem development. Cell. 2011;145(2):242–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.024%/ Copyright (c) 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 21496644.

32. Rast MI, Simon R. The meristem-to-organ boundary: more than an extremity of anything. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18(4):287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.05.005 18590819.

33. Li X, Qin G, Chen Z, Gu H, Qu LJ. A gain-of-function mutation of transcriptional factor PTL results in curly leaves, dwarfism and male sterility by affecting auxin homeostasis. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;66(3):315–27. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9272-6 18080804.

34. Lampugnani ER, Kilinc A, Smyth DR. Auxin controls petal initiation in Arabidopsis. Development. 2013;140(1):185–94. doi: 10.1242/dev.084582 23175631.

35. Griffith ME, Da SCA, Smyth DR. PETAL LOSS gene regulates initiation and orientation of second whorl organs in the Arabidopsis flower. Development. 1999;126(24):5635–44. 10572040.

36. Lampugnani ER, Kilinc A, Smyth DR. PETAL LOSS is a boundary gene that inhibits growth between developing sepals in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2012;71(5):724–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05023.x %/ (c) 2012 The Authors. The Plant Journal (c) 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 22507233.

37. Dinneny JR, Yadegari R, Fischer RL, Yanofsky MF, Weigel D. The role of JAGGED in shaping lateral organs. Development. 2004;131(5):1101–10. doi: 10.1242/dev.00949 14973282.

38. Ohno CK, Reddy GV, Heisler MG, Meyerowitz EM. The Arabidopsis JAGGED gene encodes a zinc finger protein that promotes leaf tissue development. Development. 2004;131(5):1111–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.00991 14973281.

39. Dinneny JR, Weigel D, Yanofsky MF. NUBBIN and JAGGED define stamen and carpel shape in Arabidopsis. Development. 2006;133(9):1645–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.02335 16554365.

40. Norberg M, Holmlund M, Nilsson O. The BLADE ON PETIOLE genes act redundantly to control the growth and development of lateral organs. Development. 2005;132(9):2203–13. doi: 10.1242/dev.01815 15800002.

41. Xu M, Hu T, McKim SM, Murmu J, Haughn GW, Hepworth SR. Arabidopsis BLADE-ON-PETIOLE1 and 2 promote floral meristem fate and determinacy in a previously undefined pathway targeting APETALA1 and AGAMOUS-LIKE24. Plant J. 2010;63(6):974–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04299.x %/ (c) 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation (c) 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 20626659.

42. McKim SM, Stenvik GE, Butenko MA, Kristiansen W, Cho SK, Hepworth SR, et al. The BLADE-ON-PETIOLE genes are essential for abscission zone formation in Arabidopsis. Development. 2008;135(8):1537–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.012807 18339677.

43. Hepworth SR, Zhang Y, McKim S, Li X, Haughn GW. BLADE-ON-PETIOLE-dependent signaling controls leaf and floral patterning in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17(5):1434–48. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.030536 15805484.

44. Jun JH, Ha CM, Fletcher JC. BLADE-ON-PETIOLE1 coordinates organ determinacy and axial polarity in arabidopsis by directly activating ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2. Plant Cell. 2010;22(1):62–76. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070763 20118228.

45. Lincoln C, Long J, Yamaguchi J, Serikawa K, Hake S. A knotted1-like homeobox gene in Arabidopsis is expressed in the vegetative meristem and dramatically alters leaf morphology when overexpressed in transgenic plants. Plant Cell. 1994;6(12):1859–76. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.12.1859 7866029.

46. Ha CM, Jun JH, Nam HG, Fletcher JC. BLADE-ON-PETIOLE1 encodes a BTB/POZ domain protein required for leaf morphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45(10):1361–70. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch201 15564519.

47. Khan M, Xu M, Murmu J, Tabb P, Liu Y, Storey K, et al. Antagonistic interaction of BLADE-ON-PETIOLE1 and 2 with BREVIPEDICELLUS and PENNYWISE regulates Arabidopsis inflorescence architecture. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(2):946–60. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.188573 22114095.

48. Mallory AC, Hinze A, Tucker MR, Bouche N, Gasciolli V, Elmayan T, et al. Redundant and specific roles of the ARGONAUTE proteins AGO1 and ZLL in development and small RNA-directed gene silencing. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(9):e1000646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000646 19763164.

49. Zhang X, Zhou Y, Ding L, Wu Z, Liu R, Meyerowitz EM. Transcription Repressor HANABA TARANU Controls Flower Development by Integrating the Actions of Multiple Hormones, Floral Organ Specification Genes, and GATA3 Family Genes in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2013;25(1):83–101. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.107854 23335616.

50. Bartrina I, Otto E, Strnad M, Werner T, Schmulling T. Cytokinin regulates the activity of reproductive meristems, flower organ size, ovule formation, and thus seed yield in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2011;23(1):69–80. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.079079 21224426.

51. Goldshmidt A, Alvarez JP, Bowman JL, Eshed Y. Signals derived from YABBY gene activities in organ primordia regulate growth and partitioning of Arabidopsis shoot apical meristems. Plant Cell. 2008;20(5):1217–30. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057877 18469164.

52. Venglat SP, Sawhney VK. Benzylaminopurine induces phenocopies of floral meristem and organ identity mutants in wild-type Arabidopsis plants. Planta. 1996;198(3):480–7. 8717139.

53. Vroemen CW, Mordhorst AP, Albrecht C, Kwaaitaal MA, de Vries SC. The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON3 gene is required for boundary and shoot meristem formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2003;15(7):1563–77. 12837947.

54. Schiessl K, Muino JM, Sablowski R. Arabidopsis JAGGED links floral organ patterning to tissue growth by repressing Kip-related cell cycle inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(7):2830–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320457111 24497510.

55. Sauret-Gueto S, Schiessl K, Bangham A, Sablowski R, Coen E. JAGGED controls Arabidopsis petal growth and shape by interacting with a divergent polarity field. PLoS Biol. 2013;11(4):e1001550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001550 23653565.

56. Han YY, Zhang C, Yang HB, Jiao YL. Cytokinin pathway mediates APETALA1 function in the establishment of determinate floral meristems in Arabidopsis. PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. 2014;111(18):6840–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318532111 24753595

57. Greenboim-Wainberg Y, Maymon I, Borochov R, Alvarez J, Olszewski N, Ori N, et al. Cross talk between gibberellin and cytokinin: the Arabidopsis GA response inhibitor SPINDLY plays a positive role in cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell. 2005;17(1):92–102. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.028472 15608330.

58. Richter R, Behringer C, Muller IK, Schwechheimer C. The GATA-type transcription factors GNC and GNL/CGA1 repress gibberellin signaling downstream from DELLA proteins and PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTORS. Genes Dev. 2010;24(18):2093–104. doi: 10.1101/gad.594910 20844019.

59. Lynn K, Fernandez A, Aida M, Sedbrook J, Tasaka M, Masson P, et al. The PINHEAD/ZWILLE gene acts pleiotropically in Arabidopsis development and has overlapping functions with the ARGONAUTE1 gene. Development. 1999;126(3):469–81. 9876176.

60. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8%/ Copyright 2001 Elsevier Science (USA). 11846609.

61. Maldiney R LBSI. A biotin-avidin-based enzyme-immunoassay to quantify three phytohormone: auxin, abscisic-acid and zeatin-riboside. J. Immunol.Meth.; 1986. p. 151–8%\ 2014-08-30 22 : 17 : 00.

62. Xu B, Li Z, Zhu Y, Wang H, Ma H, Dong A, et al. Arabidopsis genes AS1, AS2, and JAG negatively regulate boundary-specifying genes to promote sepal and petal development. Plant Physiol. 2008;146(2):566–75. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113787 18156293.

63. Gordon SP, Heisler MG, Reddy GV, Ohno C, Das P, Meyerowitz EM. Pattern formation during de novo assembly of the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Development. 2007;134(19):3539–48. doi: 10.1242/dev.010298 17827180.

64. Walter M, Chaban C, Schutze K, Batistic O, Weckermann K, Nake C, et al. Visualization of protein interactions in living plant cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Plant J. 2004;40(3):428–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02219.x 15469500.

65. Waadt R, Kudla J. In Planta Visualization of Protein Interactions Using Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC). CSH Protoc. 2008;2008. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4995 21356813.

66. Gendrel AV, Lippman Z, Martienssen R, Colot V. Profiling histone modification patterns in plants using genomic tiling microarrays. Nat Methods. 2005;2(3):213–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0305-213 16163802.

67. Merika M, Orkin SH. DNA-binding specificity of GATA family transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(7):3999–4010. 8321207.

68. Ko LJ, Engel JD. DNA-binding specificities of the GATA transcription factor family. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(7):4011–22. 8321208.

69. Zhang X, Madi S, Borsuk L, Nettleton D, Elshire RJ, Buckner B, et al. Laser microdissection of narrow sheath mutant maize uncovers novel gene expression in the shoot apical meristem. PLoS genetics. 2007;3(6):e101. 17571927

70. Smyth DR, Bowman JL, Meyerowitz EM. Early flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1990;2(8):755–67. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.8.755 2152125.

71. Girin T, Paicu T, Stephenson P, Fuentes S, Korner E, O'Brien M, et al. INDEHISCENT and SPATULA interact to specify carpel and valve margin tissue and thus promote seed dispersal in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011;23(10):3641–53. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.090944 21990939.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek The Chromatin Protein DUET/MMD1 Controls Expression of the Meiotic Gene during Male Meiosis inČlánek Tissue-Specific Gain of RTK Signalling Uncovers Selective Cell Vulnerability during Embryogenesis

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 9- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Retraction: RNAi-Dependent and Independent Control of LINE1 Accumulation and Mobility in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Signaling from Within: Endocytic Trafficking of the Robo Receptor Is Required for Midline Axon Repulsion

- A Splice Region Variant in Lowers Non-high Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Protects against Coronary Artery Disease

- The Chromatin Protein DUET/MMD1 Controls Expression of the Meiotic Gene during Male Meiosis in

- A NIMA-Related Kinase Suppresses the Flagellar Instability Associated with the Loss of Multiple Axonemal Structures

- Slit-Dependent Endocytic Trafficking of the Robo Receptor Is Required for Son of Sevenless Recruitment and Midline Axon Repulsion

- Expression of Concern: Protein Under-Wrapping Causes Dosage Sensitivity and Decreases Gene Duplicability

- Mutagenesis by AID: Being in the Right Place at the Right Time

- Identification of as a Genetic Modifier That Regulates the Global Orientation of Mammalian Hair Follicles

- Bridges Meristem and Organ Primordia Boundaries through , , and during Flower Development in

- Evaluating the Performance of Fine-Mapping Strategies at Common Variant GWAS Loci

- KLK5 Inactivation Reverses Cutaneous Hallmarks of Netherton Syndrome

- Differential Expression of Ecdysone Receptor Leads to Variation in Phenotypic Plasticity across Serial Homologs

- Receptor Polymorphism and Genomic Structure Interact to Shape Bitter Taste Perception

- Cognitive Function Related to the Gene Acquired from an LTR Retrotransposon in Eutherians

- Critical Function of γH2A in S-Phase

- Arabidopsis AtPLC2 Is a Primary Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C in Phosphoinositide Metabolism and the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response

- XBP1-Independent UPR Pathways Suppress C/EBP-β Mediated Chondrocyte Differentiation in ER-Stress Related Skeletal Disease

- Integration of Genome-Wide SNP Data and Gene-Expression Profiles Reveals Six Novel Loci and Regulatory Mechanisms for Amino Acids and Acylcarnitines in Whole Blood

- A Genome-Wide Association Study of a Biomarker of Nicotine Metabolism

- Cell Cycle Regulates Nuclear Stability of AID and Determines the Cellular Response to AID

- A Genome-Wide Association Analysis Reveals Epistatic Cancellation of Additive Genetic Variance for Root Length in

- Tissue-Specific Gain of RTK Signalling Uncovers Selective Cell Vulnerability during Embryogenesis

- RAB-10-Dependent Membrane Transport Is Required for Dendrite Arborization

- Basolateral Endocytic Recycling Requires RAB-10 and AMPH-1 Mediated Recruitment of RAB-5 GAP TBC-2 to Endosomes

- Dynamic Contacts of U2, RES, Cwc25, Prp8 and Prp45 Proteins with the Pre-mRNA Branch-Site and 3' Splice Site during Catalytic Activation and Step 1 Catalysis in Yeast Spliceosomes

- ARID1A Is Essential for Endometrial Function during Early Pregnancy

- Predicting Carriers of Ongoing Selective Sweeps without Knowledge of the Favored Allele

- An Interaction between RRP6 and SU(VAR)3-9 Targets RRP6 to Heterochromatin and Contributes to Heterochromatin Maintenance in

- Photoreceptor Specificity in the Light-Induced and COP1-Mediated Rapid Degradation of the Repressor of Photomorphogenesis SPA2 in Arabidopsis

- Autophosphorylation of the Bacterial Tyrosine-Kinase CpsD Connects Capsule Synthesis with the Cell Cycle in

- Multimer Formation Explains Allelic Suppression of PRDM9 Recombination Hotspots

- Rescheduling Behavioral Subunits of a Fixed Action Pattern by Genetic Manipulation of Peptidergic Signaling

- A Gene Regulatory Program for Meiotic Prophase in the Fetal Ovary

- Cell-Autonomous Gβ Signaling Defines Neuron-Specific Steady State Serotonin Synthesis in

- Discovering Genetic Interactions in Large-Scale Association Studies by Stage-wise Likelihood Ratio Tests

- The RCC1 Family Protein TCF1 Regulates Freezing Tolerance and Cold Acclimation through Modulating Lignin Biosynthesis

- The AMPK, Snf1, Negatively Regulates the Hog1 MAPK Pathway in ER Stress Response

- The Parkinson’s Disease-Associated Protein Kinase LRRK2 Modulates Notch Signaling through the Endosomal Pathway

- Multicopy Single-Stranded DNA Directs Intestinal Colonization of Enteric Pathogens

- Recurrent Domestication by Lepidoptera of Genes from Their Parasites Mediated by Bracoviruses

- Three Different Pathways Prevent Chromosome Segregation in the Presence of DNA Damage or Replication Stress in Budding Yeast

- Identification of Four Mouse Diabetes Candidate Genes Altering β-Cell Proliferation

- The Intolerance of Regulatory Sequence to Genetic Variation Predicts Gene Dosage Sensitivity

- Synergistic and Dose-Controlled Regulation of Cellulase Gene Expression in

- Genome Sequence and Transcriptome Analyses of : Metabolic Tools for Enhanced Algal Fitness in the Prominent Order Prymnesiales (Haptophyceae)

- Ty3 Retrotransposon Hijacks Mating Yeast RNA Processing Bodies to Infect New Genomes

- FUS Interacts with HSP60 to Promote Mitochondrial Damage

- Point Mutations in Centromeric Histone Induce Post-zygotic Incompatibility and Uniparental Inheritance

- Genome-Wide Association Study with Targeted and Non-targeted NMR Metabolomics Identifies 15 Novel Loci of Urinary Human Metabolic Individuality

- Outer Hair Cell Lateral Wall Structure Constrains the Mobility of Plasma Membrane Proteins

- A Large-Scale Functional Analysis of Putative Target Genes of Mating-Type Loci Provides Insight into the Regulation of Sexual Development of the Cereal Pathogen

- A Genetic Selection for Mutants Reveals an Interaction between DNA Polymerase IV and the Replicative Polymerase That Is Required for Translesion Synthesis

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Arabidopsis AtPLC2 Is a Primary Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C in Phosphoinositide Metabolism and the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response

- Bridges Meristem and Organ Primordia Boundaries through , , and during Flower Development in

- KLK5 Inactivation Reverses Cutaneous Hallmarks of Netherton Syndrome

- XBP1-Independent UPR Pathways Suppress C/EBP-β Mediated Chondrocyte Differentiation in ER-Stress Related Skeletal Disease

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání