-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Three Different Pathways Prevent Chromosome Segregation in the Presence of DNA Damage or Replication Stress in Budding Yeast

Genetic inheritance during cell proliferation requires chromosome duplication (replication) and segregation of the replicated chromosomes to the two daughter cells. In response to the presence of DNA damage, cells block chromosome segregation to avoid the inheritance of damaged, incompletely replicated chromosomes. Failure to do so results in loss of genomic integrity. Here we show that three different, redundant pathways are responsible for such control in budding yeast, a model eukaryotic organism. One of the pathways had been described before and blocks the separation of the replicated chromosomes. We show now that two additional pathways inhibit the essential pro-mitotic Cyclin Dependent Kinase (M-CDK) activity. One of them involves the conserved inhibition of M-CDK through tyrosine phosphorylation, which was puzzlingly dispensable in the response to challenged replication in budding yeast. We show that the reason for such dispensability is the existence of redundant control of M-CDK activity by Rad53. Rad53 is part of a surveillance mechanism termed the S phase checkpoint that detects and responds to replication insults. Such control mechanism has been proposed to constitute an anti-cancer barrier in human cells.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005468

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005468Summary

Genetic inheritance during cell proliferation requires chromosome duplication (replication) and segregation of the replicated chromosomes to the two daughter cells. In response to the presence of DNA damage, cells block chromosome segregation to avoid the inheritance of damaged, incompletely replicated chromosomes. Failure to do so results in loss of genomic integrity. Here we show that three different, redundant pathways are responsible for such control in budding yeast, a model eukaryotic organism. One of the pathways had been described before and blocks the separation of the replicated chromosomes. We show now that two additional pathways inhibit the essential pro-mitotic Cyclin Dependent Kinase (M-CDK) activity. One of them involves the conserved inhibition of M-CDK through tyrosine phosphorylation, which was puzzlingly dispensable in the response to challenged replication in budding yeast. We show that the reason for such dispensability is the existence of redundant control of M-CDK activity by Rad53. Rad53 is part of a surveillance mechanism termed the S phase checkpoint that detects and responds to replication insults. Such control mechanism has been proposed to constitute an anti-cancer barrier in human cells.

Introduction

Cells are continuously exposed to spontaneous DNA damage. Proliferating cells are particularly vulnerable during chromosome replication in S phase. Replication forks stall as a result of shortage of deoxynucleotides (replication stress), or the presence of DNA lesions that block the progression of the replisome [1,2]. In eukaryotic cells a surveillance mechanism, the S phase checkpoint, is activated by stalled replication forks. The checkpoint blocks anaphase, thus avoiding the segregation of damaged or incompletely replicated chromosomes. The checkpoint response has been proposed to constitute an anti-cancer barrier in human cells, preventing genomic instability in early tumorigenesis [3–6].

Despite the relevance of such control, how the S phase checkpoint blocks progression into mitosis in the model eukaryotic organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae is still unclear. In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe paralog kinases Wee1 and Mik1 inhibit mitotic Cdk1 (M-CDK) activity by tyrosine phosphorylation [7–12]. Predictably, segregation of incompletely replicated or damaged chromosomes occurs when such control is abrogated [7,12,13]. M-CDK regulation through Wee1 phosphorylation of a conserved N-terminal Tyr residue has been shown to be conserved in higher eukaryotes [14–19]. However, Cdk1 tyrosine phosphorylation is dispensable in the response to genotoxic insults in S phase in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae. Cells carrying a non-phosphorylatable Cdk1 allele remain competent to block progression into mitosis [20–22].

Pds1/securin is essential to block anaphase in response to DNA damage sensed in G2 phase generated by γ-irradiation or with a cdc13 mutant [23–28]. Pds1 inhibits Esp1/separase, a protease that promotes sister chromatid separation by cleaving the Mcd1 subunit of cohesin [23,29,30]. However, pds1 mutants remain competent to block mitosis in the presence of replication stress [23,31], suggesting that additional layers of control are in place.

We show here that the S phase checkpoint prevents chromosome segregation through downregulation of M-CDK activity and Pds1/securin stabilization. Swe1 and Rad53 redundantly inhibit M-CDK activity, which explains the dispensability of Swe1 in budding yeast. When M-CDK regulation is bypassed in cells lacking Pds1/securin, cells segregate damaged, incompletely replicated chromosomes. Significantly, the presence of Swe1 alone is sufficient to block aberrant segregation in rad53 pds1 mutants.

Results

The S phase checkpoint inhibits mitotic cyclin dependent kinase activity in vivo

S. cerevisiae appears to be an exception as to how eukaryotic cells block chromosome segregation in response to challenged DNA replication. Mutant cells where the Swe1 control on Cdk1 has been disrupted remain viable when exposed to genotoxic insults ([20,21] and Supplementary S1A Fig). In addition, both swe1 null mutants and cells carrying a non-phosphorylatable allele of Cdk1 are competent to prevent mitosis in the presence of DNA damage (S1B Fig).

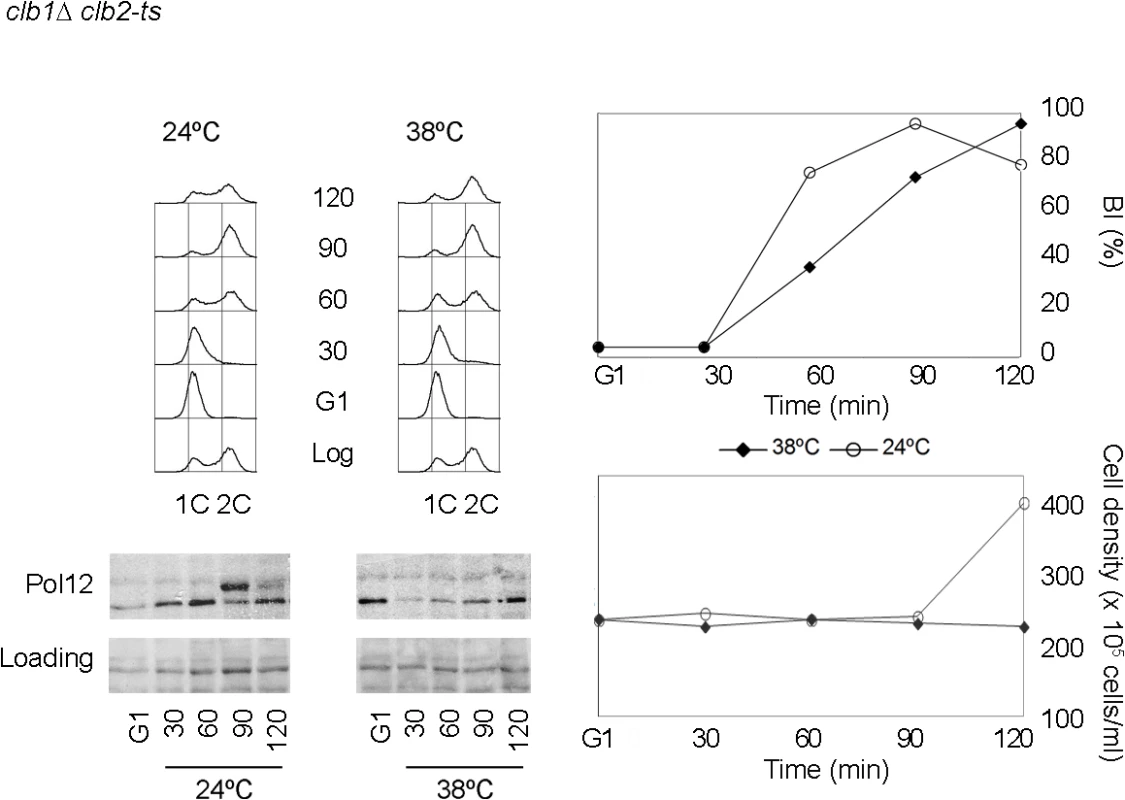

To start dissecting how budding yeast cells block mitosis, we explored whether M-CDK activity is downregulated in response to genotoxic stress. It had been previously shown that phosphorylation of the B subunit of DNA polymerase alpha-primase (Pol12 herein) is delayed in cells exposed to replication stress [32]. Pol12 is used as a marker of G2/M-CDK activity [33,34]. To distinguish whether G2-CDK or M-CDK activity is responsible for Pol12 phosphorylation, we took advantage of a clb1Δ clb2-ts mutant [35]. In such strain the only mitotic cyclin present is a conditional, thermosensitive allele of Clb2 [35]. Cells were synchronized in G1 and then released at either permissive temperature (24°C) or restrictive temperature (38°C) (Fig 1). In both cases cells bud and DNA is replicated with identical kinetics. At the permissive temperature Pol12 phosphorylation is detected after DNA replication is completed and before cell division takes place. When cells are released at restrictive temperature M-CDK activity is abolished, whereas CDK activity associated with S and G2 cyclins remains unaffected. At such temperature Pol12 remains unphosphorylated through the duration of the experiment, indicating that Pol12 is a bona fide, specific M-CDK substrate. Likewise, we confirmed Mob1 as another bona fide M-CDK substrate (S2A Fig).

Fig. 1. Pol12 is a bona fide specific M-CDK substrate that can be used to monitor M-CDK activity in vivo.

A clb1Δ clb2-ts strain (strain Y3000) was grown at 24°C. At mid-exponential phase cells were synchronized in G1 phase with the pheromone alpha-factor (G1). Cells were then released into S phase either at permissive (24°C) or restrictive (38°C) temperature and collected at the indicated times (min). Whole cell extracts were resolved immunoblotted against the B subunit of DNA polymerase alpha-primase (Pol12). A Ponceau S-stained region of the same membrane used for Western blotting is shown as a loading control. Cells entered cell cycle normally at both temperatures, as shown by the flow cytometry analysis of DNA content (upper left panel) and budding indexes (BI %). However, whereas cells at the permissive temperature enter mitosis and eventually divide (increase in cell density), lack of M-CDK activity at the restrictive temperature prevents progression into mitosis and cell division. We therefore used Pol12 phosphorylation to monitor M-CDK activity in vivo in the presence of genotoxic stress. Cells were synchronously released from G1 into S phase either in the presence or in the absence of hydroxyurea. When cells are released into an unperturbed S phase, Pol12 is phosphorylated by 50 minutes after release (Fig 2A, YPD). However, Pol12 remains unphosphorylated for the duration of the experiment when released in the presence of replication stress (Fig 2A, HU). These results indicate that M-CDK activity is downregulated in response to replication stress.

Fig. 2. M-CDK activity is inhibited in response to replication stress in a Mec1 dependent manner.

(A) Pol12 phosphorylation is inhibited in response to replication stress. Wild type cells (strain YGP20) were grown to mid-exponential phase (Log), synchronized in G1 phase with the pheromone alpha-factor (G1), then released into S phase in the absence (YPD) or in the presence of 200 mM hydroxyurea (HU). Cells were collected at the indicated times (min). Whole cell extracts were immunoblotted against Pol12 and Clb2. A Ponceau S-stained region of the same membrane used for Western blotting is shown as a loading control. Budding indexes (BI %) and cell density of the culture are shown as a measure of synchronicity and cell cycle progression. Cells in rich medium (YPD) are able to divide upon completion mitosis, as assessed by the increase in cell density. Cells in the presence of replication stress bud normally but fail to replicate, as assessed by flow cytometry analysis of DNA content. (B) Rad53 is dispensable to inhibit Pol12 phosphorylation in response to replication stress. Null rad53 cells (strain YGP24) were treated and analyzed as in (A). (C) Mec1 dependent inhibition of Pol12 phosphorylation in response to replication stress. Null mec1 cells (strain YGP123) were treated and analyzed as in (A). To explore whether M-CDK inhibition is mediated by the S phase checkpoint, we analyzed Pol12 phosphorylation in checkpoint mutant strains. Null rad53 mutant cells, lacking the checkpoint effector kinase, remain competent to block the phosphorylation of Pol12 in response to replication stress (Fig 2B). However, phosphorylation of Pol12 occurs in cells lacking Mec1, the central transducer kinase, indicating that the S phase checkpoint regulates M-CDK activity in vivo (Fig 2C). Similar results using Mob1 as an in vivo marker of M-CDK activity (S2B Fig) rule out that the observed inhibition is Pol12-specific. Identical results were also obtained when replication was instead challenged by DNA damage (S3 Fig).

These results indicate that the S phase checkpoint downregulates M-CDK activity in response to genotoxic stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Contrary to the response to osmotic stress [36], the S phase checkpoint does not abolish the expression of mitotic cyclin Clb2 (Figs 2 and S3 and S4). Clb2 accumulation occurs despite the general downregulation of transcription from the CLB2 cluster reported as part of the checkpoint response to genotoxic stress [37–42]. Our observation (S4 Fig) agrees with a previous report that shows that transcriptional downregulation in response to genotoxic stress affects the expression of some of the proteins in the cluster, such as Alk1 and Hst3, but only delays the presence of others such as Clb2 [42]. Clb2 eventually reaches levels equivalent to those in an unperturbed cycle, but cells continue to block mitosis. Therefore regulation of Clb2 expression cannot account for the control of mitosis in response to genotoxic insults during DNA replication.

Finally, we asked whether deletion of Rad53 and Chk1, the two effector kinases under Mec1, would phenocopy for the Mec1 deletion. Strikingly, rad53 chk1 double null mutant cells are able to block M-CDK activity in response to replication stress (S5 Fig), suggesting the presence an additional effector pathway under Mec1.

Rad53 and Swe1 redundantly inhibit mitotic cyclin dependent kinase activity

Our results show that the S phase checkpoint central kinase Mec1 is required to downregulate M-CDK activity in response to genotoxic stress, whereas the two downstream kinases Rad53 and Chk1 can be deleted with no loss of control. In search of the missing downstream effector pathway, we examined potential roles for Swe1. In the fission yeast S. pombe M-CDK activity is downregulated in response to genotoxic stress through Wee1 dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Cdk1 [7,12,13,43]. The dispensability of such regulation in S. cerevisiae may either indicate that the control is not conserved or, alternatively, that redundant controls are in place. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Cdk1 results in M-CDK inhibition in response to a number of cellular stresses, such as cytoskeletal perturbations, sub-optimal cell size, or osmotic stress [36,44–49]. Although this control appears dispensable, Swe1 also phosphorylates the tyrosine 19 of Cdk1 in response to replication stress ([20] and S6A Fig).

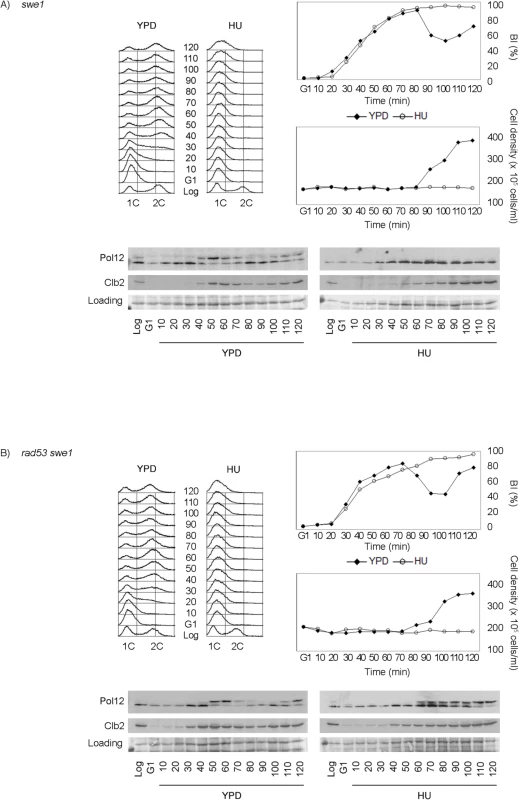

We therefore explored whether Swe1 is part of the response that downregulates M-CDK activity when DNA replication is challenged. We first asked whether Swe1 is required to suppress Pol12 phosphorylation in response to replication stress. Work with null swe1 cells shows that Pol12 remains unphosphorylated when exposed to replication stress (Fig 3A). We next monitored Pol12 phosphorylation in a double rad53 swe1 null mutant exposed to replication stress. The rad53 swe1 mutant is unable to inhibit Pol12 phosphorylation in the presence of replication stress (Fig 3B), whereas Swe1 and Rad53 are individually dispensable. Identical results were obtained when replication was instead challenged by DNA damage (S3 Fig). In all, our results show that Swe1 contributes to M-CDK inhibition redundantly with the S phase checkpoint effector kinase Rad53.

Fig. 3. Rad53 and Swe1 redundantly inhibit Pol12 phosphorylation in response to replication stress.

(A) Swe1 is dispensable to inhibit M-CDK activity in response to replication stress. Null swe1 cells (strain YGP98) were grown to mid-exponential phase (Log), synchronized in G1 phase with the pheromone alpha-factor (G1), then released into S phase in the absence (YPD) or in the presence of 200 mM hydroxyurea (HU). Cells were collected at the indicated times (min). Whole cell extracts were immunoblotted against Pol12 and Clb2. A Ponceau S-stained region of the same membrane used for Western blotting is shown as a loading control. Budding indexes (BI %) and cell density of the culture are shown as a measure of synchronicity and cell cycle progression. Flow cytometry analysis of DNA content shows that cells released in the presence of 200 mM hydroxyurea fail to replicate despite they bud normally. (B) Cells lacking Swe1 and Rad53 fail to inhibit M-CDK activity in response to replication stress. Double null mutant rad53 swe1 cells (strain YRP11) were treated and analyzed as in (A). Same results are obtained with the hypomorphic rad53-21 allele, indicating that the phenotype is specific to Rad53 and is not related to the accompanying sml1 deletion (S6B Fig).

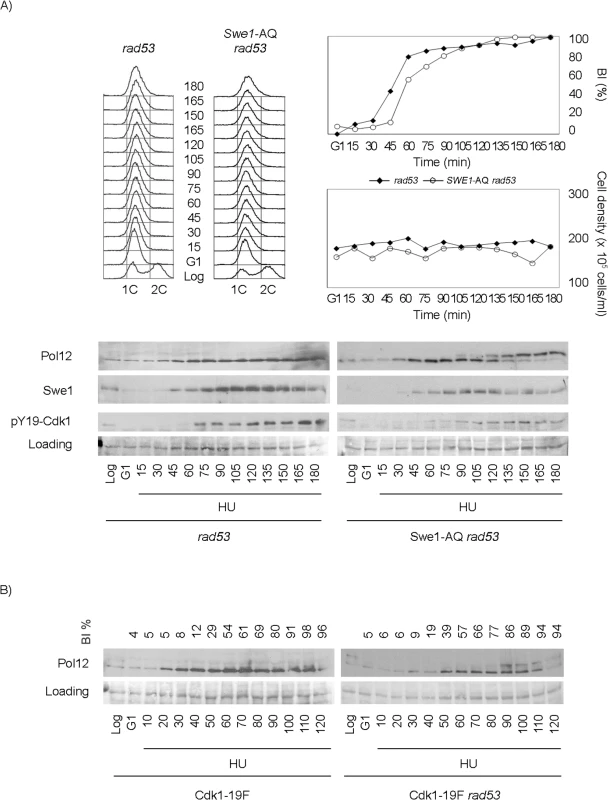

The downregulation of M-CDK activity is abrogated either by deletion of the checkpoint upstream kinase Mec1 or by the double deletion of Swe1 and the checkpoint downstream kinase Rad53. Such observation places Swe1 under Mec1. We therefore explored a direct control of Swe1 by Mec1. Mec1 is a member of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase superfamily that phosphorylates on SQ or TQ motifs. Swe1 contains a single SQ motif, S385Q. Mass spectrometry analysis confirmed that the site is phosphorylated in Swe1 purified from cells exposed to replication stress. In addition, the site is phosphorylated in the presence of replication stress, but not during an unperturbed S phase (S7 Fig). We next explored whether such phosphorylation plays a role in the control of M-CDK activity. We generated a strain carrying the non-phosphorylatable allele A385Q (Swe1-AQ) as the only source of Swe1. The allele is functional based on two evidences. One, cells carrying the Swe1-AQ allele do not display the characteristic round phenotype of swe1 loss of function mutants [50] (S8A Fig). Two, Swe1-AQ phosphorylates Cdk1 at Tyr19 in an unperturbed cell cycle at a level comparable to wild type Swe1 (S8B Fig). We next asked whether the Swe1-AQ allele abrogates the control of M-CDK activity when combined with the rad53 mutation as the swe1 deletion does. The Swe1-AQ rad53 mutant indeed fails to block M-CDK in response to replication stress (Fig 4A). This result further supports Swe1 as a downstream effector of Mec1.

Fig. 4. Swe1 and Cdk1 phosphorylation at Tyr19 are required for the regulation of M-CDK activity in response to replication stress.

Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase (Log), synchronized in G1 phase with the pheromone alpha-factor (G1), then released into S phase in the presence of 200 mM hydroxyurea (HU). Cells were collected at the indicated times (min). Whole cell extracts were immunoblotted against Pol12, Swe1 or with antibodies that specifically recognize Cdk1 phosphorylated at tyrosine 19 (pY19-Cdk1), as indicated. Ponceau S-stained regions of the same membranes used for Western blotting are shown as a loading control. Budding indexes (BI %) of the cell cultures are shown as a measure of synchronicity and cell cycle progression. (A) A Swe1-AQ allele mimics the swe1 deletion when combined with the rad53 mutation (strain YRP100). A rad53 mutant strain (YGP117) is used as a control of wild type Swe1. Cell density and flow cytometry analysis of DNA content show that cells released in the presence of 200 mM hydroxyurea fail to replicate and divide despite they bud normally. (B) A non-phosphorylatable Cdk1-19F allele mimics the swe1 deletion when combined with the rad53 mutation (strain YRP48) but fails to abrogate M-CDK inhibition on its own (strain YRP70). Finally, because Swe1 is expected to regulate Cdk1 activity through Tyr19 phosphorylation [51], a non-phosphorylatable Cdk1-19F allele should mimic the swe1 deletion. As predicted, a Cdk1-19F rad53 double mutant strain also fails to block Pol12 phosphorylation in response to replication stress (Fig 4B). Significantly, Cdk1-19F cells, that bypass the control by Swe1 but possess a functional Rad53, remain competent to block M-CDK activity in response to replication stress.

Three different pathways prevent chromosome segregation in the presence of genotoxic stress

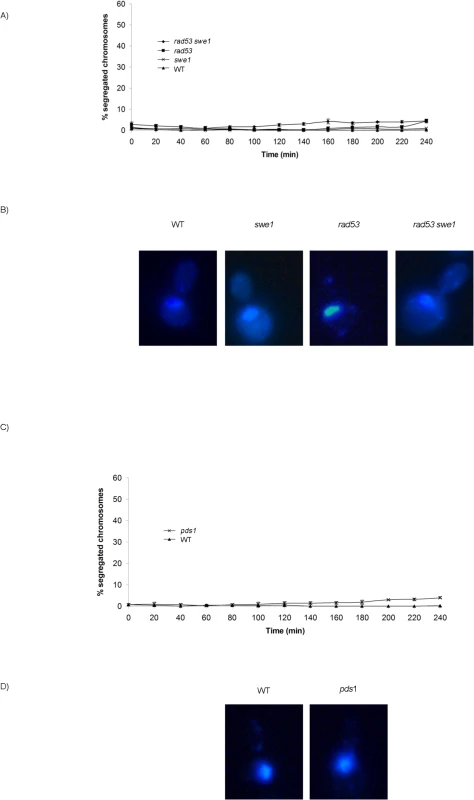

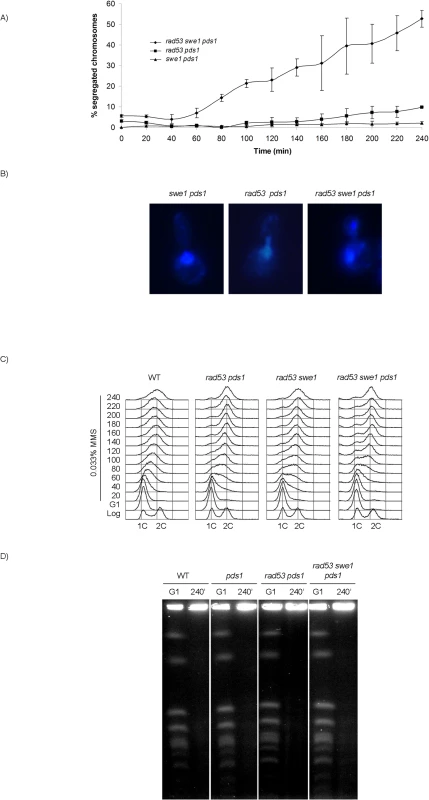

M-CDK activity is essential for mitosis. Cells lacking mitotic cyclins Clb1 and Clb2 arrest with a single undivided nucleus and a short spindle [52,53]. We thus studied the relevance of the Swe1 and Rad53 control of M-CDK to block chromosome segregation in response to challenged DNA replication. Cells were synchronized in G1 phase and then released into S phase in the presence of the DNA damaging agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS). Under such conditions chromosome segregation is inhibited in wild type cells, which show a single DNA mass throughout the duration of the experiment (Fig 5A and 5B). Similar results are obtained with rad53 swe1 double mutant cells, in spite of their inability to inhibit M-CDK activity. Therefore, unrestrained M-CDK activity is not enough to promote chromosome segregation in the presence of DNA lesions that activate the S phase checkpoint.

Fig. 5. Neither unrestrained M-CDK activity alone nor lack of Pds1/securin alone are enough to abrogate the block of chromosome segregation in the presence of DNA damage.

(A) Mutant rad53 swe1 cells remain competent to block the segregation of damaged chromosomes. Percentage of cells showing segregated masses of DNA. Wild type (WT, strain YGP20), rad53 swe1 (strain YGP121), rad53 (strain YGP38), and swe1 (strain YGP98) cells were grown to mid-exponential phase (Log), synchronized in G1 phase with the pheromone alpha-factor (G1), then released into S phase in the presence of 0.033% MMS. Cells were collected at the indicated times (min). Fixed cells were stained with DAPI to visualize DNA by fluorescence microscopy. 120 cells were counted in each of 3 independent experiments. Data are represented as mean ± SD (error bars). (B) Representative cells 240 minutes after the release from G1. (C-D) The absence of Pds1/securin is not sufficient to allow chromosome segregation in the presence of DNA damage in S phase. Wild type cells (WT, YGP20) and null pds1 cells (strain YRP33) were treated and analyzed as in (A-B). Checkpoint stabilization of Pds1/securin is essential to block chromosome segregation in response to DNA damage sensed in G2 phase [23–28]. However, our results show that Pds1 is dispensable to block chromosome segregation in response to DNA methylation damage. No segregation images are detected in pds1 mutants even 240 min after release from G1, (Fig 5C and 5D). Similar results are obtained when S phase is challenged with hydroxyurea (S9A Fig), in agreement with previous results showing that Pds1/securin is dispensable to block segregation in response to replication stress [23,31].

From our results it can be concluded that neither uninhibited M-CDK activity alone, nor the loss of Pds1/securin on its own, result in chromosome segregation when DNA replication is challenged. It is possible that downregulation of M-CDK or stabilization of Pds1/securin are each sufficient to block anaphase. We therefore explored the control of mitosis in a rad53 swe1 pds1 mutant in the presence of MMS. The triple mutant indeed fails to block chromosome segregation. Over 50% of the population show segregated DNA masses 240 min after release from G1 phase (Fig 6A and 6B), and nearly all cells show some degree of chromosome segregation. Similar results were obtained under replication stress (S9B Fig). Under these conditions replication stalls soon after the initiation of replication, and chromosomes remain largely unreplicated.

Fig. 6. Rad53, Swe1 and Pds1/securin redundantly block chromosome segregation in response to DNA damage.

(A) Segregation of damaged chromosomes in a triple rad53 swe1 pds1 mutant. Percentage of cells showing segregated masses of DNA. Cultures of swe1 pds1 (strain YRP34), rad53 pds1 (strain YGP208), and rad53 swe1 pds1 (strain YGP201) were grown to mid-exponential phase (Log), synchronized in G1 phase with the pheromone alpha-factor (G1), then released into S phase in the presence of 0.033% MMS. Cells were collected at the indicated times (min). Fixed cells were stained with DAPI to visualize DNA by fluorescence microscopy. 120 cells were counted in each of 3 independent experiments. Data are represented as mean ± SD (error bars). (B) Representative cells of strains analyzed in (A), 240 minutes after the release from G1. Only cells lacking a visible DNA link were scored. (C) Bulk DNA content of cells from the experiment described above and wild type cells (WT), as analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Chromosome replication is not completed by the end of the experiment. Wild type (WT, YGP20), pds1 (YRP33), rad53 pds1 (strain YGP208), and rad53 swe1 pds1 (strain YGP201) cells were synchronized in G1 with the pheromone alpha-factor and released into S phase in the presence of 0.033% MMS. Chromosomes of cells in G1 arrest and after 240 min in MMS were analyzed by Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE). Incompletely replicated chromosomes fail to enter the PFGE gel. Checkpoint mutants are unable to slow down DNA replication in response to genotoxic stress [54]. For that reason, the bulk of chromosome replication is apparently completed by the end of the experiment (Fig 6C). However, checkpoint mutants undergo irreversible fork collapse in the presence of genotoxic stress, leaving stretches of unreplicated chromosomes [55,56]. We confirmed that to be the case also in our experiment. Chromosome electrophoresis of cells from the 240 min time point confirms that chromosomes remain incompletely replicated, as they fail to enter the gel (Fig 6D). Therefore, the rad53 swe1 pds1 mutant allows the segregation of damaged, incompletely replicated chromosomes.

To rule out that the observed phenotype results from defects specific to the pds1 deletion [23,57,58], a thermosensitive allele of cohesin (scc1-73) was used in PDS1+ cells. The triple swe1 rad53 scc1-73 mutant is unable to block chromosome replication in the presence of DNA methylation damage (S10A Fig).

We showed above that our results place Swe1 under Mec1 in the downregulation of M-CDK activity. We therefore asked whether such control is relevant also in the control of chromosome segregation in response to genotoxic stress, exploring whether the Swe1-AQ allele may substitute for the Swe1 deletion. The Swe1-AQ allele indeed abrogates the cells ability to block chromosome segregation in the presence of DNA damage in a rad53 pds1 background (S10B Fig).

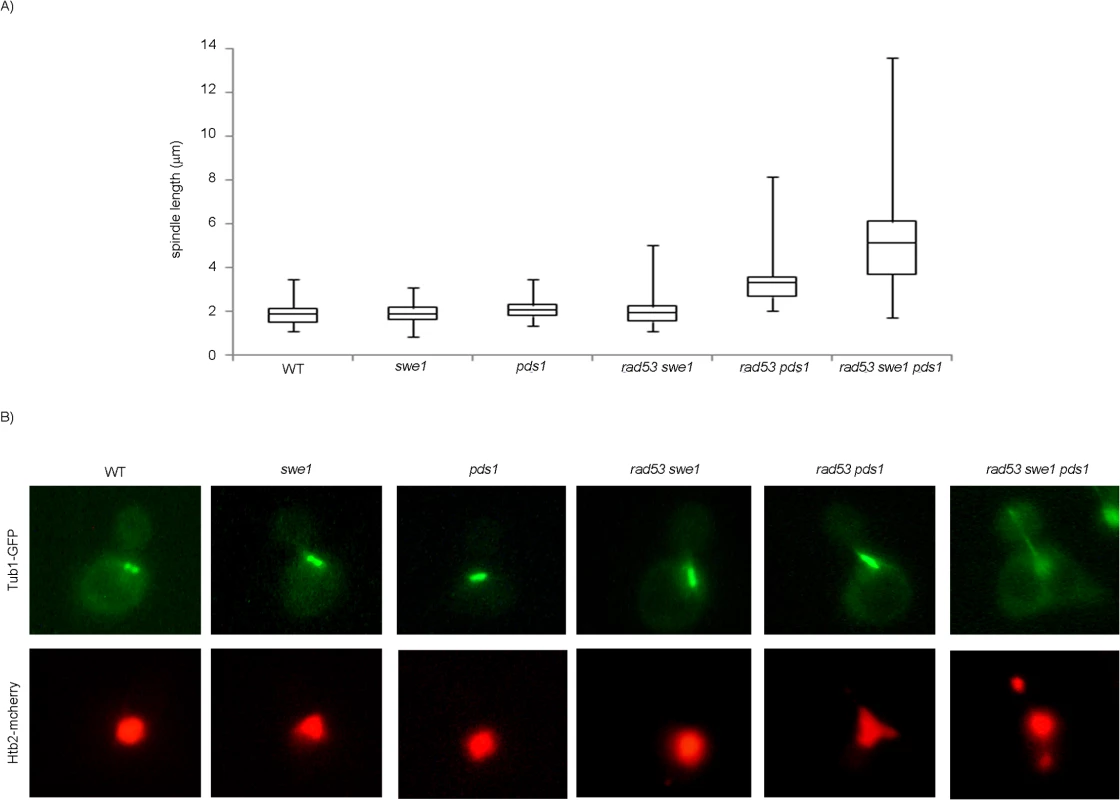

Finally we quantified spindle lengths in the presence of DNA damage. Cells in anaphase show two separate nuclear masses and spindles longer than 5 μm [59]. The chromosome segregation observed in the triple mutant swe1 rad53 pds1 in the presence of DNA damage correlates with anaphase-long spindles (Fig 7). However, SWE1+ cells lacking Rad53 and Pds1/securin show shorter spindles, indicating that Swe1 alone is sufficient to block anaphase in response to genotoxic stress.

Fig. 7. Mutant rad53 swe1 pds1 cells elongate spindles in the presence of DNA damage.

Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase, synchronized in G1 phase with the pheromone alpha-factor, then released into S phase in the presence of 0.033% MMS. Results correspond to cells 240 minutes after the release from G1. (A) Spindle lengths were measured in wild type (WT, strain YGP20), swe1 (YGP98), pds1 (strain YRP33), rad53 swe1 (YGP121), rad53 pds1 (strain YGP208), and rad53 swe1 pds1 (strain YGP201) cells. Cells were fixed, probed with anti-tubulin antibody, to visualize spindles, and stained with Hoechst 33258, to visualize DNA by fluorescence microscopy. Spindle length in 200 cells for each strain were measured and represented as box-and-whisker plots. (B) Representative cells obtained by double fluorescence with wild type (WT, strain YRP117), swe1 (YRP118), pds1 (strain YRP159), rad53 swe1 (YRP165), rad53 pds1 (strain YRP164), and rad53 swe1 pds1 (strain YRP144) cells. Spindles (Tub1-GFP) and chromatin (Htb2-mCherry) and were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Discussion

Our results provide an explanation to the longstanding conundrum of the dispensability of the S. cerevisiae Wee1 ortholog to block mitosis in response to genotoxic stress. Swe1 and checkpoint kinase Rad53 redundantly inhibit M-CDK activity. In addition, Pds1/securin blocks chromosome segregation in swe1 rad53 mutants that are unable to downregulate M-CDK activity.

Downregulation of M-CDK through phosphorylation of a conserved N-terminal Tyr residue by kinases of the Wee1 family is conserved from fission yeast to higher eukaryotes [7,12–19,43]. However, the relevance of such control in the response to genotoxic insults during DNA replication appears to vary across species. Dependence of mitosis on DNA synthesis is lost when the control of Cdk1 by Wee1 is circumvented in fission yeast [7]. However, a non-phosphorylatable Cdk1 allele fails to permit mitotic events in human cells under genotoxic stress [60]. Likewise, budding yeast cells carrying a non-phosphorylatable allele of Cdk1 remain viable when exposed to genotoxic insults [20,21]. In addition, we show that both swe1 null mutants and cells carrying a non-phosphorylatable allele of Cdk1 are competent to prevent mitosis when DNA replication is challenged.

The dispensability of Swe1 in the control of mitosis in response to genotoxic stress in budding yeast is also compatible with the existence of a redundant control [20,21]. In fact, Swe1 has been shown to play a role to delay mitosis in response to cytoskeletal perturbations [44–46], sub-optimal cell size [47–49], and in the response to osmotic stress [36]. In addition, mitotic events occur slightly earlier in swe1 mutants in an unperturbed cell cycle [35,46,48,61]. We now unveil the existence of an additional, S phase checkpoint dependent control that redundantly downregulates M-CDK activity in response to challenged DNA replication. Either Swe1 or the S phase checkpoint effector kinase Rad53 are individually sufficient to hold M-CDK activity in response to genotoxic stress. Only when both pathways are disrupted, cells fail to block the phosphorylation of a bona fide specific M-CDK substrate.

It will be of interest to investigate whether such redundant control is conserved in other species. Bypass of Cdk1 tyrosine phosphorylation fails to abrogate downregulation of Cdk1 activity associated with cyclin B1 in response to genotoxic stress in human cells [60]. Also, recent results in fission yeast suggest the existence of additional layers of regulation. A synthetic form of Cdk1, lacking the regulatory phosphorylation site, still exhibits a significant degree of cell size homeostasis [62].

We also show that different pathways redundantly prevent chromosome segregation when DNA replication is challenged. Neither deregulation of M-CDK activity, nor stabilization of Pds1/securin alone are enough to allow chromosome segregation under such conditions.

M-CDK activity is essential to trigger anaphase at two distinct levels. One of them, M-CDK activation of APC/C–Cdc20, is required for the destruction of Pds1/securin that blocks sister chromatid segregation [63,64]. A second requirement, M-CDK promotes the full spindle elongation necessary for chromosome segregation [35]. However, the swe1 rad53 mutant, which is unable to downregulate M-CDK activity when DNA replication is challenged, remains competent to block chromosome segregation.

We therefore explored whether Pds1/securin plays a role in the control of mitosis in response to genotoxic insults in S phase. Stabilization of Pds1/securin by the DNA damage checkpoint is essential to block anaphase in response to genotoxic insults sensed in G2 phase [23–28]. However, our results show that Pds1 is dispensable to block chromosome segregation in response to DNA methylation damage and replication stress. Our results are in agreement with previous works showing that Pds1 is dispensable to block segregation in response to replication stress [23,31]. In the same direction, forced cleavage of cohesin fails to allow spindle elongation when cells are exposed to the DNA methylating agent MMS [65].

A plausible scenario would be that in response to genotoxic stress, cells redundantly inhibit chromosome segregation through M-CDK inhibition and Pds1 stabilization. Our observations are consistent with such a dual control mechanism. We now show that Pds1 is dispensable to block anaphase in response to genotoxic stress for as long as downregulation of M-CDK is in force. We also show that M-CDK control by the S phase checkpoint is dispensable only while Pds1 is in place. When both controls are abrogated, cells are unable to block the segregation of damaged or incompletely replicated chromosomes. As unreplicated regions persist, chromosomes can only undergo aberrant segregation, and DNA segregation is unequal.

It is reasonable that progression to mitosis is differently regulated in response to genotoxic insults in S or in G2 phase. By the time that the DNA damage checkpoint responds to cdc13 or cdc9 DNA lesions in G2/M, M-CDK is already active [21]. In this case, Rad53 is precisely required to maintain stable Clb2-Cdk1 activity as a way to block premature mitotic exit [26]. At this time of the cell cycle inhibition of M-CDK leads to premature cytokinesis and septation [66], which would lead to loss of viability and aneuploidy. Therefore, cells may rely on Pds1 stabilization alone to block anaphase [23–28]. Downregulation of M-CDK to prevent mitosis seems to provide an additional layer of control when DNA replication is challenged. Also, the G2/M block to cell cycle progression in response to DNA double strand breaks is abrogated by individual mec1, rad53 or pds1 mutants [67]. As shown here, this is not the case in the response to genotoxic stress in S phase.

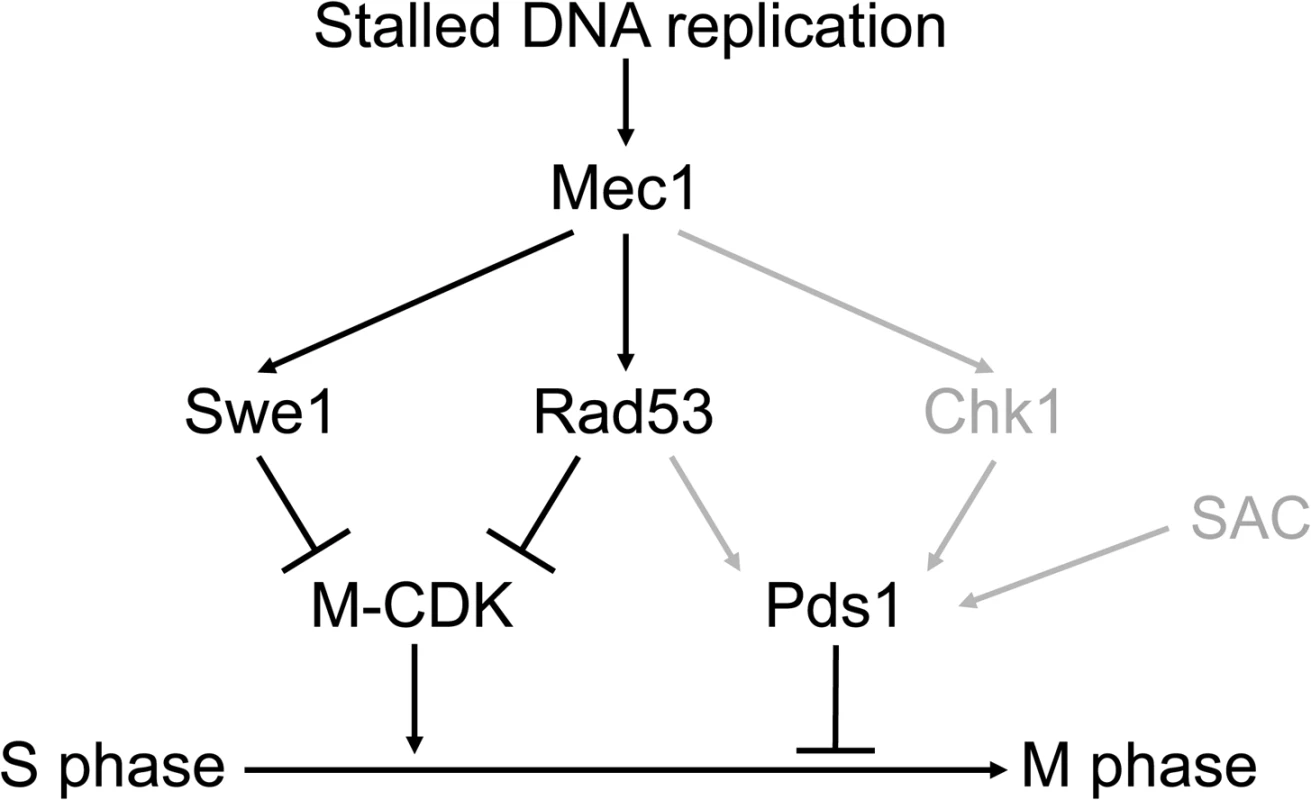

Our results are summarized in Fig 8. Three different pathways, mediated by Swe1, Rad53 and Pds1, block the segregation of damaged, incompletely replicated chromosomes. Each of them is individually sufficient. Genotoxic insults that block replication fork progression, such as replication stress or DNA methylation damage, activate the S phase checkpoint central transducer kinase Mec1. Mec1 is required both to block M-CDK activity, as shown here, and to stabilize Pds1/securin, as has been shown before [23–28]. Only when cells are unable to inhibit M-CDK activity and to stabilize Pds1 the control on chromosome segregation is abrogated.

Fig. 8. Three different pathways prevent chromosome segregation in the presence of genotoxic stress.

Molecular diagram showing the three pathways that block Mitotic Cyclin Dependent Kinase activity and anaphase in response to genotoxic stress. Swe1 and the S phase checkpoint effector kinase Rad53 are individually sufficient to block M-CDK activity. Our results place Swe1 as a downstream effector of the S phase checkpoint. M-CDK inhibition and Pds1/securin stabilization are individually sufficient to prevent anaphase. Only when the three pathways are disrupted cells fail to block the segregation of damaged or incompletely replicated chromosomes. In grey, regulatory pathways taken from previous works [23–28]. The Spindle Assembly Checkpoint (SAC) is included in the model as it may also play a role in Pds1 stabilization [76]. Mec1 inhibits M-CDK activity through Swe1 and Rad53. Our results place Swe1 as a downstream effector of the S phase checkpoint. Swe1 is phosphorylated at a putative Mec1 phosphorylation site in the presence of replication stress. Significantly, a Swe1 allele that cannot be phosphorylated by Mec1 is as defective as a swe1 null mutant with respect to M-CDK regulation. Future work will be aimed at the elucidation of the molecular mechanism that SQ phosphorylation plays. At this time, we discard the idea that Mec1 phosphorylation is required for Swe1 activation. For one, Swe1 is known to be active in an unperturbed cell cycle, when Mec1 remains inactive (see for instance S8B Fig, left). In addition, the non-phosphorylatable Swe1(AQ) allele is catalytically active (S8B Fig, right), despite it fails to block M-CDK activity (Fig 4A) and chromosome segregation (S10B Fig) similarly to the swe1 deletion. Significantly, a recent work dealing with the regulation of SFF transcription in response to DNA damage also places Swe1/Mih1 under the S phase checkpoint [39].

Downregulation of M-CDK activity by the checkpoint effector kinase Rad53 had not been described before. It will be of interest to explore in the future whether Rad53 acts directly on the M-phase cyclin-Cdk1 complex or on essential M-CDK substrates.

Our results thus reconcile the dispensability of Swe1 in the response to genotoxic insults during DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Notably, the presence of Swe1 alone is sufficient to block the aberrant segregation of damaged, incompletely replicated chromosomes in a rad53 pds1 mutant. In the presence of genotoxic stress the double mutant shows stretched nuclei by the bud neck, and longer, albeit pre-anaphasic, spindles compared with wild type cells. However over 90% of cells show a single mass of DNA. Likely in this scenario Swe1 limits the M-CDK activity required for spindles to reach the length required for chromosome segregation [35].

In summary, our work uncovers the existence of multiple controls to block segregation of damaged chromosomes in budding yeast in contrast to the simplicity reported in S. pombe [7,12–19,43].The complexity found in S. cerevisiae may be conserved in other organisms. It will be worthwhile to study whether a similar control operates in human cells [60]. The ability to block the segregation of damaged, incompletely replicated chromosomes is key to prevent the genomic instability that fuels cancerous transformation.

Materials and Methods

Strains used in this work are listed in S1 Table. All strains are derived from S. cerevisiae W303-1a [68]. Cell synchronization, generation of genotoxic stress, flow cytometry analysis of DNA content, whole cell extract preparation, and western blot analysis were carried out as previously described [69–71]. Cells were cultured at 30°C, except for the microscopy experiments in which all strains were grown at 24°C to avoid the temperature sensitivity of pds1 mutants. The B subunit of the DNA polymerase alpha-primase (Pol12) was detected in Western blot using 6D2 mouse monoclonal antibody [72]. Swe1-AQ-13myc was detected with 9E10 anti-myc mouse monoclonal antibody. Mob1-3HA was detected with 12CA5 anti-HA mouse monoclonal antibody. Cdc28 and Cdc28 phosphorylation in tyrosine 19 were detected with anti-Cdc28 (yC-20 Santa Cruz Biotechnology) goat polyclonal and anti-pY15-Cdc2 rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling #9111). Clb2 was detected with anti-Clb2 (y-180 Santa Cruz Biotechnology) rabbit polyclonal antibody. Phosphorylated SQ was detected with Phospho-(Ser/Thr) ATM/ATR substrate rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling #2851). Nuclei were visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy of cells fixed in -20°C methanol and stained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) as described [71]. Three independent experiments were carried out for each strain. 120 cells were counted per time-point and experiment. For quantitation of spindle length, spindles were visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy of cells fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde as described [71]. Anti-tubulin mouse monoclonal antibody TAT1 [73], and Alexa 488 coupled anti-mouse antibody (Invitrogen), were used as primary and secondary antibodies respectively. Alternatively, spindles and nuclei were visualized in by immunofluorescence microscopy in live cells using histone H2B-mCherry TUB1-GFP strains. Phosphorylation analysis was carried out using label-free quantitative MS as described [74]. Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis was carried out as described [75].

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Weinert TA, Kiser GL, Hartwell LH. Mitotic checkpoint genes in budding yeast and the dependence of mitosis on DNA replication and repair. Genes Dev. 1994;8 : 652–665. 7926756

2. Allen JB, Zhou Z, Siede W, Friedberg EC, Elledge SJ. The SAD1/RAD53 protein kinase controls multiple checkpoints and DNA damage-induced transcription in yeast. Genes Dev. 77030.; 1994;8 : 2401–2415. 7958905

3. Bartkova J, Rezaei N, Liontos M, Karakaidos P, Kletsas D, Issaeva N, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature. 2006;444 : 633–637. 17136093

4. Bartkova J, Horejsi Z, Koed K, Kramer A, Tort F, Zieger K, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434 : 864–870. 15829956

5. Gorgoulis VG, Vassiliou L V, Karakaidos P, Zacharatos P, Kotsinas A, Liloglou T, et al. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature. 2005;434 : 907–913. 15829965

6. Bartek J, Bartkova J, Lukas J. DNA damage signalling guards against activated oncogenes and tumour progression. Oncogene. 2007;26 : 7773–7779. 18066090

7. Enoch T, Nurse P. Mutation of fission yeast cell cycle control genes abolishes dependence of mitosis on DNA replication. Cell. 1990;60 : 665–673. 2406029

8. Rhind N, Furnari B, Russell P. Cdc2 tyrosine phosphorylation is required for the DNA damage checkpoint in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 1997;11 : 504–511. 9042863

9. Rhind N, Russell P. Tyrosine phosphorylation of cdc2 is required for the replication checkpoint in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18 : 3782–3787. 9632761

10. Baber-Furnari BA, Rhind N, Boddy MN, Shanahan P, Lopez-Girona A, Russell P. Regulation of mitotic inhibitor Mik1 helps to enforce the DNA damage checkpoint. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11 : 1–11. 10637286

11. McGowan CH, Russell P. Human Wee1 kinase inhibits cell division by phosphorylating p34cdc2 exclusively on Tyr15. EMBO J. 1993;12 : 75–85. 8428596

12. Gould KL, Nurse P. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the fission yeast cdc2+ protein kinase regulates entry into mitosis. Nature. 1989;342 : 39–45. 2682257

13. Lundgren K, Walworth N, Booher R, Dembski M, Kirschner M, Beach D. Mik1 and Wee1 Cooperate in the Inhibitory Tyrosine Phosphorylation of Cdc2. Cell. 1991;64 : 1111–1122. 1706223

14. Dunphy WG, Newport JW. Fission yeast p13 blocks mitotic activation and tyrosine dephosphorylation of the Xenopus cdc2 protein kinase. Cell. 1989;58 : 181–191. 2473838

15. Gautier J, Matsukawa T, Nurse P, Maller J. Dephosphorylation and activation of Xenopus p34cdc2 protein kinase during the cell cycle. Nature. 1989;339 : 626–629. 2543932

16. Draetta G, Beach D. Activation of cdc2 protein kinase during mitosis in human cells: cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation and subunit rearrangement. Cell. 1988;54 : 17–26. 3289755

17. Draetta G, Piwnica-Worms H, Morrison D, Druker B, Roberts T, Beach D. Human cdc2 protein kinase is a major cell-cycle regulated tyrosine kinase substrate. Nature. 1988;336 : 738–744. 2462672

18. Morla AO, Draetta G, Beach D, Wang JY. Reversible tyrosine phosphorylation of cdc2: dephosphorylation accompanies activation during entry into mitosis. Cell. 1989;58 : 193–203. 2473839

19. Solomon MJ, Glotzer M, Lee TH, Philippe M, Kirschner MW. Cyclin activation of p34cdc2. Cell. 1990;63 : 1013–1024. 2147872

20. Sorger PK, Murray AW. S-phase feedback control in budding yeast independent of tyrosine phosphorylation of p34cdc28. Nature. 1992;355 : 365–368. 1731250

21. Amon A, Surana U, Muroff I, Nasmyth K. Regulation of p34CDC28 tyrosine phosphorylation is not required for entry into mitosis in S. cerevisiae. Nature. 1992;355 : 368–371. 1731251

22. Stueland CS, Lew DJ, Cismowski MJ, Reed SI. Full activation of p34CDC28 histone H1 kinase activity is unable to promote entry into mitosis in checkpoint-arrested cells of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13 : 3744–3755. 8388545

23. Yamamoto A, Guacci V, Koshland D. Pds1p, an inhibitor of anaphase in budding yeast, plays a critical role in the APC and checkpoint pathway(s). J Cell Biol. 1996;133 : 99–110. 8601617

24. Cohen-Fix O, Koshland D. The anaphase inhibitor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pds1p is a target of the DNA damage checkpoint pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94 : 14361–14366. 9405617

25. Gardner R, Putnam CW, Weinert T. RAD53, DUN1 and PDS1 define two parallel G2/M checkpoint pathways in budding yeast. EMBO J. 1999;18 : 3173–3185. 10357828

26. Sanchez Y, Bachant J, Wang H, Hu F, Liu D, Tetzlaff M, et al. Control of the DNA damage checkpoint by chk1 and rad53 protein kinases through distinct mechanisms. Science. 1999;286 : 1166–1171. 10550056

27. Wang H, Liu D, Wang Y, Qin J, Elledge SJ. Pds1 phosphorylation in response to DNA damage is essential for its DNA damage checkpoint function. Genes Dev. 2001;15 : 1361–1372. 11390356

28. Agarwal R, Tang Z, Yu H, Cohen-Fix O. Two distinct pathways for inhibiting pds1 ubiquitination in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2003;278 : 45027–45033. 12947083

29. Ciosk R, Zachariae W, Michaelis C, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Nasmyth K. An ESP1/PDS1 complex regulates loss of sister chromatid cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition in yeast. Cell. 1998;93 : 1067–76. 9635435

30. Uhlmann F, Lottspeich F, Nasmyth K. Sister-chromatid separation at anaphase onset is promoted by cleavage of the cohesin subunit Scc1. Nature. 1999;400 : 37–42. 10403247

31. Clarke DJ, Segal M, Mondesert G, Reed SI. The Pds1 anaphase inhibitor and Mec1 kinase define distinct checkpoints coupling S phase with mitosis in budding yeast. Curr Biol. 1999;9 : 365–368. 10209118

32. Liu H, Wang Y. The function and regulation of budding yeast Swe1 in response to interrupted DNA synthesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17 : 2746–2756. 16571676

33. Foiani M, Liberi G, Lucchini G, Plevani P. Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the yeast DNA polymerase alpha-primase B subunit. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15 : 883–891. 7823954

34. Tanaka S, Diffley JFX. Deregulated G1-cyclin expression induces genomic instability by preventing efficient pre-RC formation. Genes Dev. 2002;16 : 2639–49. 12381663

35. Rahal R, Amon A. Mitotic CDKs control the metaphase-anaphase transition and trigger spindle elongation. Genes Dev. 2008;22 : 1534–1548. doi: 10.1101/gad.1638308 18519644

36. Clotet J, Escoté X, Adrover MA, Yaakov G, Garí E, Aldea M, et al. Phosphorylation of Hsl1 by Hog1 leads to a G2 arrest essential for cell survival at high osmolarity. EMBO J. 2006;25 : 2338–2346. 16688223

37. Gasch AP, Huang M, Metzner S, Botstein D, Elledge SJ, Brown PO. Genomic expression responses to DNA-damaging agents and the regulatory role of the yeast ATR homolog Mec1p. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12 : 2987–3003. 11598186

38. Yelamanchi SK, Veis J, Anrather D, Klug H, Ammerer G. Genotoxic stress prevents Ndd1-dependent transcriptional activation of G2/M-specific genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34 : 711–24. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01090-13 24324010

39. Edenberg ER, Mark KG, Toczyski DP. Ndd1 Turnover by SCFGrr1 Is Inhibited by the DNA Damage Checkpoint in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLOS Genet. 2015;11: e1005162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005162 25894965

40. Edenberg ER, Vashisht A, Benanti JA, Wohlschlegel J, Toczyski DP. Rad53 downregulates mitotic gene transcription by inhibiting the transcriptional activator Ndd1. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34 : 725–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01056-13 24324011

41. Jaehnig EJ, Kuo D, Hombauer H, Ideker TG, Kolodner RD. Checkpoint kinases regulate a global network of transcription factors in response to DNA damage. Cell Rep. 2013;4 : 174–88. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.041 23810556

42. Maas NL, Miller KM, DeFazio LG, Toczyski DP. Cell cycle and checkpoint regulation of histone H3 K56 acetylation by Hst3 and Hst4. Mol Cell. 2006;23 : 109–19. 16818235

43. Russell P, Nurse P. Cdc25+ Functions as an Inducer in the Mitotic Control of Fission Yeast. Cell. 1986;45 : 145–153. 3955656

44. Cid VJ, Jiménez J, Molina M, Sánchez M, Nombela C, Thorner JW. Orchestrating the cell cycle in yeast: sequential localization of key mitotic regulators at the spindle pole and the bud neck. Microbiology. 2002;148 : 2647–2659. 12213912

45. Lew DJ. The morphogenesis checkpoint: How yeast cells watch their figures. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2003. pp. 648–653. 14644188

46. Lianga N, Williams EC, Kennedy EK, Doré C, Pilon S, Girard SL, et al. A Wee1 checkpoint inhibits anaphase onset. J Cell Biol. 2013;201 : 843–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201212038 23751495

47. Rupes I. Checking cell size in yeast. Trends in Genetics. 2002. pp. 479–485. 12175809

48. Harvey SL, Kellogg DR. Conservation of mechanisms controlling entry into mitosis: Budding yeast wee1 delays entry into mitosis and is required for cell size control. Curr Biol. 2003;13 : 264–275. 12593792

49. Harvey SL, Charlet A, Haas W, Gygi SP, Kellogg DR. Cdk1-dependent regulation of the mitotic inhibitor Wee1. Cell. 2005;122 : 407–420. 16096060

50. Sheu YJ, Barral Y, Snyder M. Polarized growth controls cell shape and bipolar bud site selection in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20 : 5235–47. 10866679

51. Booher RN, Deshaies RJ, Kirschner MW. Properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae wee1 and its differential regulation of p34CDC28 in response to G1 and G2 cyclins. Embo J. 1993;12 : 3417–3426. 8253069

52. Surana U, Robitsch H, Price C, Schuster T, Fitch I, Futcher AB, et al. The role of CDC28 and cyclins during mitosis in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae. Cell. Research Institute of Molecular Pathology, Vienna, Austria.; 1991;65 : 145–161. 1849457

53. Richardson H, Lew DJ, Henze M, Sugimoto K, Reed SI. Cyclin-B homologs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae function in S phase and in G2. Genes Dev. 1992;6 : 2021–2034. 1427070

54. Paulovich AG, Hartwell LH. A checkpoint regulates the rate of progression through S phase in S. cerevisiae in response to DNA damage. Cell. 1995;82 : 841–847. 7671311

55. Lopes M, Cotta-Ramusino C, Pellicioli A, Liberi G, Plevani P, Muzi-Falconi M, et al. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature. 2001;412 : 557–561. 11484058

56. Tercero JA, Diffley JF. Regulation of DNA replication fork progression through damaged DNA by the Mec1/Rad53 checkpoint. Nature. 2001;412 : 553–557. 11484057

57. Agarwal R, Cohen-Fix O. Phosphorylation of the mitotic regulator Pds1/securin by Cdc28 is required for efficient nuclear localization of Esp1/separase. Genes Dev. 2002;16 : 1371–82. 12050115

58. Hsu W-S, Erickson SL, Tsai H-J, Andrews CA, Vas AC, Clarke DJ. S-phase cyclin-dependent kinases promote sister chromatid cohesion in budding yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31 : 2470–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05323-11 21518961

59. Higuchi T, Uhlmann F. Stabilization of microtubule dynamics at anaphase onset promotes chromosome segregation. Nature. 2005;433 : 171–6. 15650742

60. Jin P, Gu Y, Morgan DO. Role of inhibitory CDC2 phosphorylation in radiation-induced G2 arrest in human cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;134 : 963–970. 8769420

61. Oikonomou C, Cross FR. Rising cyclin-CDK levels order cell cycle events. PLoS One. 2011;6: e20788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020788 21695202

62. Coudreuse D, Nurse P. Driving the cell cycle with a minimal CDK control network. Nature. 2010;468 : 1074–1079. doi: 10.1038/nature09543 21179163

63. Rudner AD, Hardwick KG, Murray AW. Cdc28 activates exit from mitosis in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 2000;149 : 1361–76. 10871278

64. Rudner AD, Murray AW. Phosphorylation by Cdc28 activates the Cdc20-dependent activity of the anaphase-promoting complex. J Cell Biol. 2000;149 : 1377–90. 10871279

65. Liang H, Lim HH, Venkitaraman A, Surana U. Cdk1 promotes kinetochore bi-orientation and regulates Cdc20 expression during recovery from spindle checkpoint arrest. EMBO J. 2012;31 : 403–416. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.385 22056777

66. Sanchez-Diaz A, Nkosi PJ, Murray S, Labib K. The Mitotic Exit Network and Cdc14 phosphatase initiate cytokinesis by counteracting CDK phosphorylations and blocking polarised growth. EMBO J. 2012;31 : 3620–3634. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.224 22872148

67. Dotiwala F, Haase J, Arbel-Eden A, Bloom K, Haber JE. The yeast DNA damage checkpoint proteins control a cytoplasmic response to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104 : 11358–63. 17586685

68. Thomas BJ, Rothstein R. Elevated recombination rates in transcriptionally active DNA. Cell. 1989;56 : 619–630. 2645056

69. Travesa A, Duch A, Quintana DG. Distinct phosphatases mediate the deactivation of the DNA damage checkpoint kinase Rad53. J Biol Chem. 2008;283 : 17123–17130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801402200 18441009

70. Duch A, Palou G, Jonsson ZO, Palou R, Calvo E, Wohlschlegel J, et al. A Dbf4 mutant contributes to bypassing the Rad53-mediated block of origins of replication in response to genotoxic stress. J Biol Chem. 2011;286 : 2486–2491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190843 21098477

71. Palou G, Palou R, Guerra-Moreno A, Duch A, Travesa A, Quintana DG. Cyclin regulation by the s phase checkpoint. J Biol Chem. 2010;285 : 26431–26440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.138669 20538605

72. Foiani M, Marini F, Gamba D, Lucchini G, Plevani P. The B subunit of the DNA polymerase alpha-primase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae executes an essential function at the initial stage of DNA replication. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14 : 923–933. 8289832

73. Woods A, Sherwin T, Sasse R, MacRae TH, Baines AJ, Gull K. Definition of individual components within the cytoskeleton of Trypanosoma brucei by a library of monoclonal antibodies. J Cell Sci. 1989;93 (Pt 3): 491–500.

74. Wang Q, Barshop WD, Bian M, Vashisht AA, He R, Yu X, et al. The Blue Light-Dependent Phosphorylation of the CCE Domain Determines the Photosensitivity of Arabidopsis CRY2. Mol Plant. 2015;8 : 631–43. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.03.005 25792146

75. Bermudez-Lopez M, Ceschia A, de Piccoli G, Colomina N, Pasero P, Aragon L, et al. The Smc5/6 complex is required for dissolution of DNA-mediated sister chromatid linkages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38 : 6502–6512. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq546 20571088

76. Garber PM, Rine J. Overlapping roles of the spindle assembly and DNA damage checkpoints in the cell-cycle response to altered chromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2002;161 : 521–34. 12072451

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek The Chromatin Protein DUET/MMD1 Controls Expression of the Meiotic Gene during Male Meiosis inČlánek Tissue-Specific Gain of RTK Signalling Uncovers Selective Cell Vulnerability during Embryogenesis

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 9- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Intrauterinní inseminace a její úspěšnost

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Retraction: RNAi-Dependent and Independent Control of LINE1 Accumulation and Mobility in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Signaling from Within: Endocytic Trafficking of the Robo Receptor Is Required for Midline Axon Repulsion

- A Splice Region Variant in Lowers Non-high Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Protects against Coronary Artery Disease

- The Chromatin Protein DUET/MMD1 Controls Expression of the Meiotic Gene during Male Meiosis in

- A NIMA-Related Kinase Suppresses the Flagellar Instability Associated with the Loss of Multiple Axonemal Structures

- Slit-Dependent Endocytic Trafficking of the Robo Receptor Is Required for Son of Sevenless Recruitment and Midline Axon Repulsion

- Expression of Concern: Protein Under-Wrapping Causes Dosage Sensitivity and Decreases Gene Duplicability

- Mutagenesis by AID: Being in the Right Place at the Right Time

- Identification of as a Genetic Modifier That Regulates the Global Orientation of Mammalian Hair Follicles

- Bridges Meristem and Organ Primordia Boundaries through , , and during Flower Development in

- Evaluating the Performance of Fine-Mapping Strategies at Common Variant GWAS Loci

- KLK5 Inactivation Reverses Cutaneous Hallmarks of Netherton Syndrome

- Differential Expression of Ecdysone Receptor Leads to Variation in Phenotypic Plasticity across Serial Homologs

- Receptor Polymorphism and Genomic Structure Interact to Shape Bitter Taste Perception

- Cognitive Function Related to the Gene Acquired from an LTR Retrotransposon in Eutherians

- Critical Function of γH2A in S-Phase

- Arabidopsis AtPLC2 Is a Primary Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C in Phosphoinositide Metabolism and the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response

- XBP1-Independent UPR Pathways Suppress C/EBP-β Mediated Chondrocyte Differentiation in ER-Stress Related Skeletal Disease

- Integration of Genome-Wide SNP Data and Gene-Expression Profiles Reveals Six Novel Loci and Regulatory Mechanisms for Amino Acids and Acylcarnitines in Whole Blood

- A Genome-Wide Association Study of a Biomarker of Nicotine Metabolism

- Cell Cycle Regulates Nuclear Stability of AID and Determines the Cellular Response to AID

- A Genome-Wide Association Analysis Reveals Epistatic Cancellation of Additive Genetic Variance for Root Length in

- Tissue-Specific Gain of RTK Signalling Uncovers Selective Cell Vulnerability during Embryogenesis

- RAB-10-Dependent Membrane Transport Is Required for Dendrite Arborization

- Basolateral Endocytic Recycling Requires RAB-10 and AMPH-1 Mediated Recruitment of RAB-5 GAP TBC-2 to Endosomes

- Dynamic Contacts of U2, RES, Cwc25, Prp8 and Prp45 Proteins with the Pre-mRNA Branch-Site and 3' Splice Site during Catalytic Activation and Step 1 Catalysis in Yeast Spliceosomes

- ARID1A Is Essential for Endometrial Function during Early Pregnancy

- Predicting Carriers of Ongoing Selective Sweeps without Knowledge of the Favored Allele

- An Interaction between RRP6 and SU(VAR)3-9 Targets RRP6 to Heterochromatin and Contributes to Heterochromatin Maintenance in

- Photoreceptor Specificity in the Light-Induced and COP1-Mediated Rapid Degradation of the Repressor of Photomorphogenesis SPA2 in Arabidopsis

- Autophosphorylation of the Bacterial Tyrosine-Kinase CpsD Connects Capsule Synthesis with the Cell Cycle in

- Multimer Formation Explains Allelic Suppression of PRDM9 Recombination Hotspots

- Rescheduling Behavioral Subunits of a Fixed Action Pattern by Genetic Manipulation of Peptidergic Signaling

- A Gene Regulatory Program for Meiotic Prophase in the Fetal Ovary

- Cell-Autonomous Gβ Signaling Defines Neuron-Specific Steady State Serotonin Synthesis in

- Discovering Genetic Interactions in Large-Scale Association Studies by Stage-wise Likelihood Ratio Tests

- The RCC1 Family Protein TCF1 Regulates Freezing Tolerance and Cold Acclimation through Modulating Lignin Biosynthesis

- The AMPK, Snf1, Negatively Regulates the Hog1 MAPK Pathway in ER Stress Response

- The Parkinson’s Disease-Associated Protein Kinase LRRK2 Modulates Notch Signaling through the Endosomal Pathway

- Multicopy Single-Stranded DNA Directs Intestinal Colonization of Enteric Pathogens

- Recurrent Domestication by Lepidoptera of Genes from Their Parasites Mediated by Bracoviruses

- Three Different Pathways Prevent Chromosome Segregation in the Presence of DNA Damage or Replication Stress in Budding Yeast

- Identification of Four Mouse Diabetes Candidate Genes Altering β-Cell Proliferation

- The Intolerance of Regulatory Sequence to Genetic Variation Predicts Gene Dosage Sensitivity

- Synergistic and Dose-Controlled Regulation of Cellulase Gene Expression in

- Genome Sequence and Transcriptome Analyses of : Metabolic Tools for Enhanced Algal Fitness in the Prominent Order Prymnesiales (Haptophyceae)

- Ty3 Retrotransposon Hijacks Mating Yeast RNA Processing Bodies to Infect New Genomes

- FUS Interacts with HSP60 to Promote Mitochondrial Damage

- Point Mutations in Centromeric Histone Induce Post-zygotic Incompatibility and Uniparental Inheritance

- Genome-Wide Association Study with Targeted and Non-targeted NMR Metabolomics Identifies 15 Novel Loci of Urinary Human Metabolic Individuality

- Outer Hair Cell Lateral Wall Structure Constrains the Mobility of Plasma Membrane Proteins

- A Large-Scale Functional Analysis of Putative Target Genes of Mating-Type Loci Provides Insight into the Regulation of Sexual Development of the Cereal Pathogen

- A Genetic Selection for Mutants Reveals an Interaction between DNA Polymerase IV and the Replicative Polymerase That Is Required for Translesion Synthesis

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Arabidopsis AtPLC2 Is a Primary Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C in Phosphoinositide Metabolism and the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response

- Bridges Meristem and Organ Primordia Boundaries through , , and during Flower Development in

- KLK5 Inactivation Reverses Cutaneous Hallmarks of Netherton Syndrome

- XBP1-Independent UPR Pathways Suppress C/EBP-β Mediated Chondrocyte Differentiation in ER-Stress Related Skeletal Disease

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání