-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

The Protein -glucosyltransferase Rumi Modifies Eyes Shut to Promote Rhabdomere Separation in

Glycosylation (addition of sugars to proteins and other organic molecules) is important for protein function and animal development. Each form of glycosylation is usually present on multiple proteins. Therefore, a major challenge in understanding the role of sugars in animal development is to identify which protein(s) modified by a specific sugar require the sugar modification for proper functionality. We have previously shown that an enzyme called Rumi adds glucose molecules to an important cell surface receptor called Notch, and that glucose plays a key role in the function of Notch both in fruit flies and in mammals. Using fruit flies, we have now identified a new Rumi target called “Eyes shut”, a secreted protein with a critical role in the optical isolation of neighboring photoreceptors in the fly eye. Our data suggest that glucose molecules on Eyes shut promote its folding and stability in a critical time window during eye development. Mutations in human Eyes shut result in a devastating form of retinal degeneration and loss of vision. Since human Eyes shut is also predicted to harbor glucose molecules, our work provides a framework to explore the role of sugar modifications in the biology of a human disease protein.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004795

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004795Summary

Glycosylation (addition of sugars to proteins and other organic molecules) is important for protein function and animal development. Each form of glycosylation is usually present on multiple proteins. Therefore, a major challenge in understanding the role of sugars in animal development is to identify which protein(s) modified by a specific sugar require the sugar modification for proper functionality. We have previously shown that an enzyme called Rumi adds glucose molecules to an important cell surface receptor called Notch, and that glucose plays a key role in the function of Notch both in fruit flies and in mammals. Using fruit flies, we have now identified a new Rumi target called “Eyes shut”, a secreted protein with a critical role in the optical isolation of neighboring photoreceptors in the fly eye. Our data suggest that glucose molecules on Eyes shut promote its folding and stability in a critical time window during eye development. Mutations in human Eyes shut result in a devastating form of retinal degeneration and loss of vision. Since human Eyes shut is also predicted to harbor glucose molecules, our work provides a framework to explore the role of sugar modifications in the biology of a human disease protein.

Introduction

Diurnal insects possess “apposition eyes” in which ommatidia are optically isolated from each other [1], [2]. In most diurnal insects like honeybee and butterflies, the apical rhodopsin-housing structures of each ommatidium—the rhabdomeres—are fused at the center. This allows the group of photoreceptors in each ommatidium to act as a single optical device [1]. A modification of the apposition eye arose during insect evolution in dipteran flies, where an extracellular lumen called the inter-rhabdomeral space (IRS) forms to separate and optically isolate the rhabdomeres in each ommatidium from one another. Due to this structural modification and the accompanying regrouping of photoreceptor axons among neighboring ommatidia, information from photoreceptor cells that receive light from the same point in the space merge on the same postsynaptic targets in the lamina [3]. This type of eye is referred to as a neural superposition eye, and these improvements allow for increased light sensitivity without sacrificing resolution [1], [4].

Separation of the rhabdomeres in flies requires an evolutionarily conserved secreted glycoprotein called Eyes shut (Eys; also called Spacemaker). eys mutant flies lack the IRS and exhibit an altered photoreceptor organization that resembles the closed rhabdom of other insects like honeybees and mosquitos [5], [6]. Eys is secreted from the stalk membrane of the photoreceptor cells in an Ire1-dependent but Sec6-independent manner to separate the rhabdomeres and open the IRS [5], [7]. Drosophila eys functions together with three other genes, crumbs (crb), prominin (prom) and chaoptin (chp), to regulate rhabdomere separation and IRS size [5], [6], [8], [9]. Genetic experiments have established that prom and eys promote rhabdomere separation but chp and crb promote rhabdomere adhesion, and that the balance between their activities results in proper IRS formation [6], [8], [9].

The Crb extracellular domain and the Eys protein are primarily composed of epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) repeats and Laminin G domains [5], [6], [10], [11]. However, the role of these protein domains and their posttranslational modifications in the function Eys and Crb is unknown. Five of the Eys EGF repeats and seven of the Crb EGF repeats contain the C1XSX(P/A)C2 consensus sequence, which predicts the addition of an O-linked glucose by the protein O-glucosyltransferase Rumi (POGLUT1 in mammals) [12], [13]. Mutations in rumi were first isolated in a genetic screen for regulators of sensory organ development in Drosophila [12]. When raised at 18°C, rumi mutants are viable and only show a mild loss of Notch signaling in certain contexts including bristle lateral inhibition and leg joint formation [12], [14]. However, when raised at higher temperatures the mutant animals show a broad and severe loss of Notch signaling, until 28–30°C, at which loss of rumi becomes larval lethal [12], [14], [15]. Mice lacking the Rumi homolog POGLUT1 die at early embryonic stages (at or before E9.5) and some of the defects observed in mutant embryos are characteristic of loss of Notch signaling [16]. Moreover, transgenic expression of human POGLUT1 in flies rescues the rumi null phenotypes, indicating that the function of Rumi is conserved [17]. Drosophila Notch has 18 Rumi target sites in its extracellular domain, most of which have been confirmed to harbor O-glucose residues [12], [18]. Moreover, serine-to-alanine mutations in the Rumi target sites of Notch result in a temperature-sensitive loss of Notch signaling [14], establishing Notch as a biologically-relevant target of Rumi in flies. However, whether Rumi and its glucosyltransferase activity are required for the function of its other potential targets like Eys and Crb and for rhabdomere separation remained unknown.

Here, we present evidence indicating that the enzymatic activity of Rumi is required for the separation of rhabdomeres in the Drosophila eye. When raised at 18°C, animals homozygous for a null allele of rumi or for a missense mutation that abolishes its protein O-glucosyltransferase activity show a highly penetrant rhabdomere attachment phenotype that cannot be explained by loss of O-glucose from Notch. Mass spectral analysis indicates that both Crb and Eys harbor O-glucose when expressed in a fly cell line. However, genetic experiments rule out Crb as a target of Rumi during rhabdomere separation. Our data indicate that O-glucosylation of Eys by Rumi promotes Eys folding and stability and thereby ensures that enough Eys is secreted into the IRS in a critical time window during the mid-pupal stage to fully separate the rhabdomeres.

Results

Mutations in rumi result in a rhabdomere attachment phenotype which starts in the mid-pupal stage

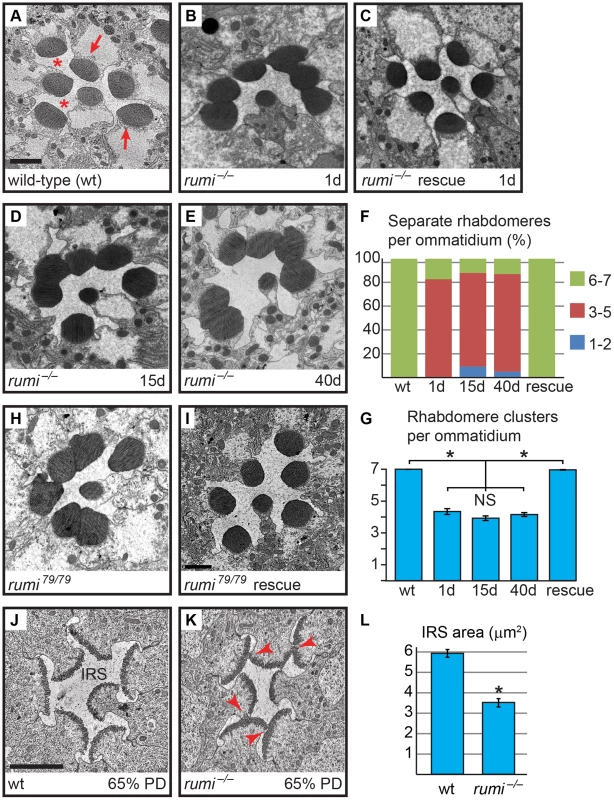

When raised at 18°C, rumi mutant animals are viable and show only a mild loss of Notch signaling in some contexts [12], [14]. To explore whether Rumi plays a role in rhabdomere morphogenesis and IRS formation, we raised animals homozygous for the protein-null allele rumiΔ26 (rumi−) in ambient light at 18°C and performed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) on adult fly eyes. In cross sections of wild-type retinas, the rhabdomeres of the seven visible photoreceptor cells are separated from neighboring rhabdomeres by the IRS [19] (Figure 1A and 1F). However, 1-day old rumi−/− animals exhibited a moderate, yet 100% penetrant, rhabdomere attachment phenotype, i.e. attachment of two or more rhabdomeres per ommatidium (Figure 1B and 1F). This phenotype can be fully rescued by P{rumigt-FLAG} (Figure 1C and 1F), a genomic transgene expressing a FLAG-tagged version of Rumi [12], indicating that attachment of rhabdomeres observed in rumi−/− flies is due to the loss of rumi. Sections of rumi−/− animals at 15 and 40 days of age show a similar degree of rhabdomere attachment, suggesting that the phenotype is not age-dependent (Figure 1D–G). Together, these observations indicate that Rumi is required for optical isolation of individual photoreceptors in the Drosophila eye.

Fig. 1. Loss of the enzymatic function of Rumi results in rhabdomere adhesion.

Shown are electron micrographs of a single ommatidium from adult (A–E,H,I) or 65% PD (J,K) from the indicated genotypes. All animals were raised at 18°C. (A) Wild-type. Arrows indicate rhabdomeres and asterisks indicate the IRS. Scale bar: 2 µm. (B) 1-day old rumi−/−. Note the attachment in the neighboring rhabdomeres. (C) 1-day old rumi−/− expressing a wild-type P{rumigt-FLAG} genomic transgene. (D,E) The rumi−/− rhabdomere attachment phenotype does not change with age, since 15-day old (D) and 40-day old (E) animals show a similar degree of attachment. (F) Percentage of number of individual rhabdomeres per ommatidia for various genotypes. At least three animals were used for each genotype. The number of ommatidia examined for each genotype is as follows: wt (50), 1d (35), 15d (66), 40d (85), rescue (126). (G) Quantification of average individual rhabdomere number per ommatidium for the data shown in F. Rhabdomere attachments in 1-day, 15-day and 40-day old rumi animals are not significantly different from one another, but are significantly different from wild-type and rescued animals (*P<0.0001). NS, not significant. (H,I) The enzymatically inactive allele rumi79 also shows a rhabdomere attachment phenotype (H), which can be rescued by one copy of the wild-type P{rumigt-FLAG} genomic transgene (I). (J,K) Ommatidia from animals at 65% PD from wild-type (J) and rumi−/− (K). Arrowheads in (K) indicate points of rhabdomere attachment. (L) Means ± SEM of IRS area in wild-type and rumi−/− at 65% PD. IRS areas were measured using ImageJ software. Unpaired t-test was used to compare wt (n = 14) and rumi−/− (n = 24) IRS, *P<0.0001. We have previously shown that Rumi primarily regulates Notch signaling through its protein O-glucosyltransferase activity [12], [14]. We wondered whether the enzymatic activity of Rumi is also required for rhabdomere separation. To test this, we performed TEM on adult Drosophila homozygous for rumi79, a severe hypomorphic allele harboring a missense mutation which abolishes the enzymatic activity of Rumi but does not affect its expression level or stability [12], [17]. rumi79/79 animals raised at 18°C also exhibit rhabdomere attachment in all ommatidia examined (Figure 1H; n>50). Surprisingly, the average number of separate rhabdomeres per ommatidium was somewhat lower in rumi79/79 animals (3.41±0.15) compared to rumi−/− animals (4.11±0.08), indicating that the rhabdomere attachment phenotype is slightly more severe in rumi79/79 animals compared to rumi−/− animals. Statistical analysis indicated that the difference between rumi79/79 and rumi−/− average rhabdomere number per ommatidia is significant (P<0.0001). Given that rumiΔ26 is a protein-null allele [12], these data suggest that rumi79 might have a dominant negative effect in the context of rhabdomere separation. However, one copy of the P{rumigt-FLAG} genomic transgene was able to fully rescue the rhabdomere attachment phenotype of rumi79/79 animals (Figure 1I, n>50). Moreover, overexpression of Rumi-G189E, which is the protein product of rumi79 [12], did not result in any rhabdomere separation defects, similar to overexpression of wild-type Rumi (Figure S1). Together, these observations suggest that rumi79 is not likely to be a dominant negative allele. Since rumi79 was generated in an EMS screen but rumiΔ26 is the product of P-element excision, the modest worsening of the rhabdomere attachment in rumi79 might be due to a genetic background effect. Taken together, these observations indicate that enzymatic activity of Rumi is required for the separation of rhabdomeres in the fly eye.

Rhabdomere morphogenesis and IRS formation occur during the second half of pupal development [19]. Until 37% pupal development (PD), the apical surfaces of photoreceptors are attached to one another and do not exhibit any microvillar structures [19]. Around 55% PD, short microvilli and neighboring stalk membranes can be seen at the apical surfaces of the developing photoreceptors, and a thin IRS has formed [19]. By 65% PD, the rhabdomeres are clearly separated from one another by the IRS (Figure 1J). Because one-day old adult rumi retinas have a well-formed IRS but exhibit rhabdomere attachment (Figure 1B), we asked whether the absence of Rumi prevents rhabdomere separation during pupal development, or whether they initially separate but subsequently attach as the pupal eye assumes its adult structure. To address this question, we performed TEM on 65% PD rumi−/− retinas grown at 18°C, and found that by 65% PD, each rumi photoreceptor harbors distinct stalk membrane and rhabdomere structures (Figure 1K). The IRS has formed but the average IRS size in mutant ommatidia (3.52±0.20 µm2) is 59% of the average IRS size in wild-type ommatidia (5.95±0.19 µm2) at a similar stage raised at the same temperature (Figure 1L, P<0.0001). Although the apical surfaces of photoreceptors adjacent to the IRS appear separated from one another, multiple local adhesions persist between the microvillar membranes of neighboring rhabdomeres (and occasionally opposing rhabdomeres) in each ommatidium (Figure 1K, arrowheads). These observations indicate that the rumi rhabdomere attachment phenotypes are evident early during rhabdomere morphogenesis and strongly suggest that proper rhabdomere separation never occurs in rumi−/− animals.

Loss of O-glucose from Notch cannot explain the rhabdomere attachment phenotype of rumi animals

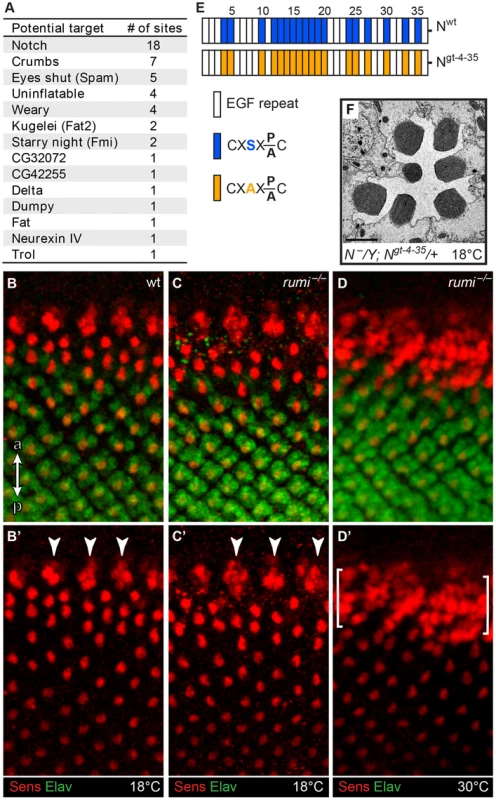

If Rumi regulates rhabdomere spacing via its protein O-glucosyltransferase (Poglut) activity, lack of glucose on Rumi target proteins is likely to be responsible for the observed phenotype. To identify all fly proteins with a potential Rumi target site, we used the MOTIF search engine (http://motif.genome.jp/MOTIF2.html) to search the Swiss-Prot and KEGG-GENES databases for Drosophila proteins harboring one or more EGF repeats with the C1XSX(P/A)C2 consensus sequence [13]. Based on this search, 14 Drosophila proteins have at least one EGF repeat with a predicted Rumi target site (Figure 2A), with Notch harboring the largest number of O-glucosylation sites, most of which have been confirmed to be efficiently O-glucosylated by Rumi [12], [13], [18]. rumi null animals raised at 18°C do not show photoreceptor specification defects characteristic of loss of Notch signaling (Figure 2B–D′), suggesting that Notch signaling is not significantly affected in rumi−/− developing photoreceptors at this temperature. Moreover, to our knowledge, Notch signaling has not been implicated in rhabdomere spacing. Nevertheless, given the broad roles that Notch plays in multiple developmental contexts, we sought to examine whether the rhabdomere spacing defects observed in rumi mutants can be explained by loss of O-glucose from Notch EGF repeats. To this end, we used a Notch genomic transgene (PBac{Ngt-4-35}) in which serine-to-alanine mutations are introduced in all 18 Rumi target sites and therefore expresses a Notch protein which cannot be O-glucosylated by Rumi [14] (Figure 2E). When reared at 18°C, the PBac{Ngt-4-35} transgene rescues the lethality of Notch null mutations, and the N−; PBac{Ngt-4-35}/+ animals only show a mild loss of Notch signaling similar to rumi mutants [14]. TEM revealed that adult N−; PBac{Ngt-4-35}/+ eyes raised at 18°C do not show any rhabdomere attachment phenotypes (Figure 2F), strongly supporting the notion that addition of O-glucose to Notch is not essential for proper rhabdomere spacing.

Fig. 2. Loss of O-glucose on Notch cannot explain the rumi−/− rhabdomere attachment phenotype.

(A) List of potential Rumi targets in flies. (B–D′) Close-ups of the third instar larval eye discs showing the developing photoreceptors in wt (B,B′), rumi−/− animals raised at 18°C (C,C′) and rumi−/− animals raised at 18°C and shifted to 30°C for four hours before dissection (D,D′). R8 photoreceptors are marked with Senseless (Sens, red) and all photoreceptors are marked with Elav (green). ‘a’ and ‘p’ in panel B show anterior and posterior, respectively, and apply to B–D′. Arrowheads in B′ and C′ mark the R8 proneural clusters before a single R8 is selected through Notch-mediated lateral inhibition. In rumi−/− animals raised at 18°C (C,C′), the R8 proneural clusters are refined into single Sens+ R8 cells, which themselves recruit other photoreceptors, similar to the wild-type animal (B,B′). In contrast, raising the rumi larvae at 30°C results in the specification of multiple R8 photoreceptor cells (the area between the brackets), indicating an impairment of the Notch-mediated lateral inhibition at this temperature. Note that R8 selection and photoreceptor recruitment is not impaired in the area posterior to the brackets because the animal was raised at 30°C only for four hours. (E) Schematic of the EGF repeats of the Notch genomic transgene used in the study. Blue and orange boxes indicate EGF repeats harboring wt and mutant Rumi consensus sequences, respectively. (F) Electron micrograph of an ommatidium of an animal expressing the mutated PBac{Notchgt-4-35} transgene in a Notch null background raised at 18°C. Scale bar: 2 µm. Crb is O-glucosylated but loss of O-glucose from Crb does not result in rhabdomere attachment

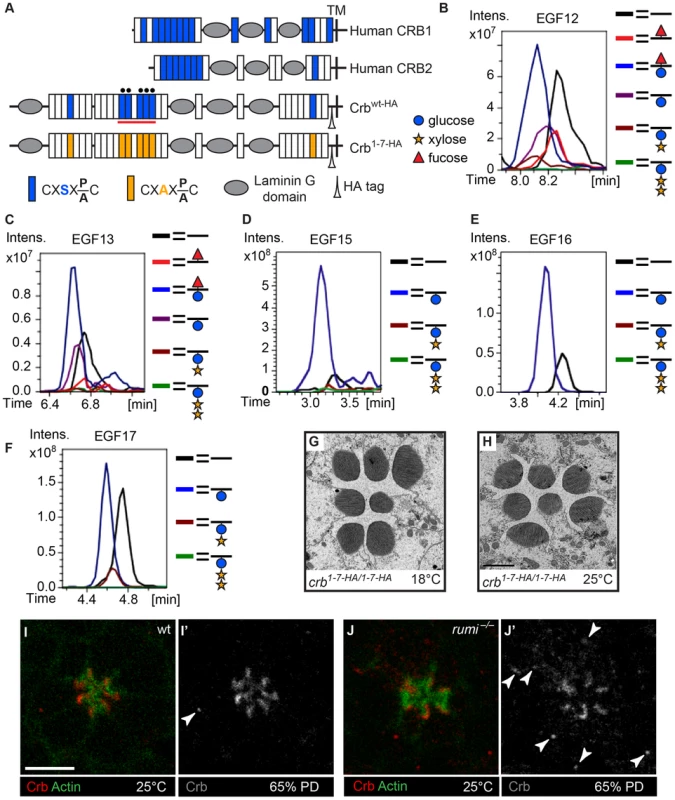

The fly protein with the second largest number of Rumi target sites is Crb (Figure 2A), an evolutionarily conserved transmembrane protein involved in the regulation of epithelial polarity, organ size, and photoreceptor development and maintenance [10], [11], [20]–[24]. Of note, crb mutant retinas exhibit attachment of neighboring rhabdomeres despite the presence of IRS [20], [21]. Seven of the Drosophila Crb EGF repeats, 13 of the human CRB1 EGF repeats and eight of the human CRB2 EGF repeats harbor Rumi target sites, suggesting that O-glucosylation might play an important role in the function of Crb (Figure 3A). We performed mass spectral analysis on peptides derived from a fragment of the Crb extracellular domain expressed in Drosophila S2 cells (Figure 3A, the red line) to examine whether Crb can be O-glucosylated in Drosophila. Indeed, peptides containing the predicted sites in this region are O-glucosylated (Figure 3B–F, Figure S2 and Figure S3). We next asked whether loss of O-glucose from Rumi target sites in Crb recapitulates the rhabdomere attachment phenotype observed in rumi mutants. Using a previously established platform [23], [25], [26], we generated a knock-in allele of crb (crb1-7-HA) with serine-to-alanine mutations in all seven Rumi target sites (Figure 3A). Animals homozygous for this allele or trans-heterozygous for this allele and the null allele crb11A22 are viable and do not exhibit any gross abnormalities when raised between 18°C and 25°C. Moreover, TEM indicates normal rhabdomere morphology and IRS formation with no defects in rhabdomere spacing in crb1-7-HA/1-7-HA animals raised at either 18°C or 25°C (Figure 3G and 3H). These observations indicate that absence of Crb O-glucosylation does not explain the rhabdomere spacing defects of rumi mutants. In agreement with these data, Crb appears to be properly localized to the stalk membrane in 65% PD rumi−/− retinas, although an increase in the number of Crb+ puncta is seen in rumi mutants raised at 25°C compared to control animals (Figure 3I–J′, arrowheads). Together, these data indicate that although O-glucose modifications might affect the trafficking of Crb, they are not essential for the function of Crb during fly embryonic development and photoreceptor morphogenesis.

Fig. 3. Loss of O-glucose on Crb cannot explain the rumi−/− rhabdomere attachment phenotype.

(A) Schematic of the human CRB1, human CRB2, and wt and mutant, HA-tagged Drosophila Crb based on the Crb-PA polypeptide (FlyBase ID: FBpp0083987). Blue and orange boxes indicate EGF repeats harboring wt and mutant Rumi consensus sequences, respectively. TM, transmembrane domain. Black circles mark EGF repeats shown in B–F. (B–F) Extracted Ion Chromatogram (EIC) data for peptides containing the O-glucose consensus site from Crb EGF12 (B), EGF13 (C), EGF15 (D), EGF16 (E) and EGF17 (F) obtained from mass spectrometry on a Crb fragment indicated by the red line in (A). Note the presence of O-glucose (blue circle) on all five EGF repeats, some of which are elongated by xylose (yellow star). Peptides from EGF12 and EGF13 also harbor O-fucose (red triangle) added to the consensus O-fucosylation sites present in these two EGF repeats. Full spectra and the peptide sequences are shown in Figure S2 and Figure S3. (G,H) crb knock-in mutants lacking all Rumi target sites and raised at 18°C (G) or 25°C (H) do not show rhabdomere attachment. Scale bar in H applies to G and H and is 2 µm. (I–J′) Loss of Rumi does not impair Crb localization to the stalk membrane. Increased Crb puncta, some of which are marked with arrowheads in J′, are seen in the photoreceptor cell body of rumi−/− ommatidia raised at 25°C (J,J′) compared to wild-type (I,I′). Actin (green) is used to mark the rhabdomeres. Crb is shown in red. Scale bar: 5 µm. Eys is a biologically-relevant target of Rumi during rhabdomere morphogenesis

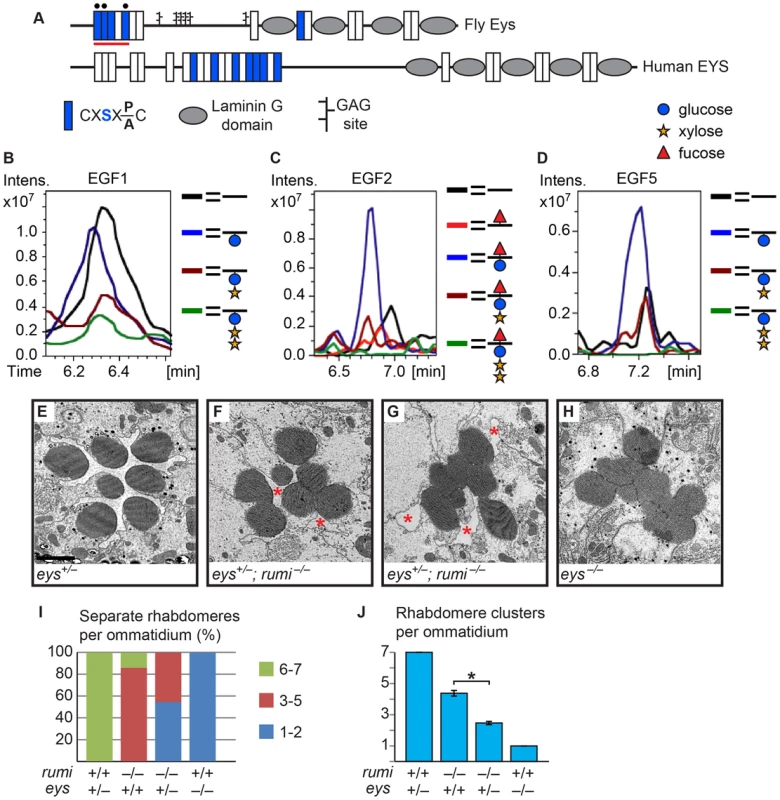

As mentioned above, another Drosophila protein with multiple predicted Rumi target sites and an IRS phenotype is Eys (Figure 2A and Figure 4A) [5], [6]. To examine whether Eys is the biologically-relevant target of Rumi in the context of rhabdomere spacing, we first performed mass spectral analysis on peptides derived from an Eys fragment harboring four Rumi target sites expressed in S2 cells (Figure 4A, the red line). So far we have been able to identify peptides corresponding to three of these sites by mass spectrometric analysis and have identified O-glucose on all three sites (Figure 4B–D and Figure S4). The Rumi target site in EGF1 appears to be less efficiently O-glucosylated compared to those in other Eys EGF repeats. Nevertheless, these data indicate that Drosophila Eys contains several bona fide Rumi targets. We next performed genetic interaction studies between rumi and eys by using the protein-null allele eys734 [5]. As reported previously, loss of one copy of eys does not cause any rhabdomere defects (Figure 4E) [5], [6]. However, removing one copy of eys in a rumi−/− background results in a strong enhancement of the rumi−/− rhabdomere attachment phenotype at 18°C (Compare Figure 4F and 4G to Figure 1B, 1D and 1E). In eys+/−; rumi−/− animals, multiple rhabdomeres collapse into one another in each ommatidium, and there is a dramatic decrease in the IRS size (Figure 4F, 4G, 4I and 4J). Of note, pockets of IRS can still be recognized in all eys+/−; rumi−/− ommatidia (Figure 4F and 4G, asterisks), in contrast to eys−/− ommatidia, which completely lack IRS (Figure 4H and 4J) [5]. This dosage-sensitive genetic interaction strongly suggests that Rumi is critical for the function of Eys, especially when Eys levels are limiting.

Fig. 4. Eys is O-glucosylated and eys genetically interacts with rumi.

(A) Schematic of the fly and human Eys proteins. Red line indicates the EGF repeats used for mass spectrometry analysis. Black circles mark EGF repeats shown in B–D. (B–D) EIC data from mass spectral analysis of EGF1 (B), EGF2 (C), and EGF5 (D). Blue peak indicates the addition of O-glucose (blue circle) onto the EGF repeat. EGF2 is also modified by O-fucose (red triangle). Rumi appears to be less efficient in O-glucosylating EGF1 of Eys compared to the other EGF repeats when expressed in S2 cells. Full spectra and the peptide sequences are shown in Figure S4. (E) An eys heterozygous ommatidium with normal rhabdomere separation. Scale bar: 2 µm. (F,G) eys+/− rumi−/− ommatidia show a dramatic enhancement of the rumi−/− phenotype. In severe cases, all the rhabdomeres are attached (G). Pockets of IRS are marked by asterisks. (H) eys null ommatidia completely lack IRS. (I) Percentage of number of individual rhabdomeres per ommatidium for various genotypes. At least three animals were used for each genotype. (J) Quantification of average individual rhabdomere number per ommatidium for the data shown in I. All pairs are significantly different from each other (*P<0.0001). Loss of Rumi results in a decrease in the extracellular level of Eys in a temperature-dependent manner

Secretion of Eys from the apical surface of the photoreceptor cells at the mid-pupal stage separates the rhabdomeres from one another and generates the IRS [5], [6]. Based on the modENCODE Temporal Expression Data accessed on FlyBase (http://flybase.org/reports/FBgn0031414.html), expression of eys sharply increases at mid-pupal stage and gradually decreases in later pupal stages. Following the initial burst of Eys expression between 50–70% PD [5] and rhabdomere separation, Eys continues to be secreted into the IRS, which gradually enlarges and assumes its adult size late in the pupal stage [5], [19]. Given the increased degree of rhabdomere attachment and the severe decrease in the IRS size in adult animals simultaneously lacking rumi and one copy of eys, we examined whether loss of Rumi affects Eys levels in the IRS. We first compared Eys expression in the early stages of IRS development between rumi−/− and control pupae raised at 18°C. At 55% PD, the rhabdomeres of control animals are separated from one another by a thin but continuous IRS filled with Eys, and only low levels of Eys can be detected in photoreceptor cell bodies (Figure 5A and 5A′) [5]. In contrast, rumi−/− ommatidia almost invariably show some degree of rhabdomere attachment and a decreased and interrupted pattern of Eys expression in the IRS (Figure 5B and 5B′). In the majority of rumi−/− ommatidia examined, decreased levels of Eys in the IRS are accompanied by increased Eys levels in the photoreceptor cell bodies (Figure 5B and 5B′). Quantification of the total pixel intensity of Eys at 55% PD in animals raised at 18°C shows that in wild-type ommatidia, 87.1±2.0% of total Eys is found in the IRS and the rest is in photoreceptor cell bodies. However, there is a statistically significant decrease in the percentage of Eys found in the IRS in rumi−/− ommatidia (63.6±6.5%, P = 0.01). These data indicate that during early stages of IRS formation, a significant amount of Eys remains inside the photoreceptor cells in rumi mutants, unlike wild-type animals, in which most of the Eys is efficiently secreted into the IRS.

Fig. 5. Loss of Rumi leads to intracellular accumulation and decreased IRS levels of Eys in a temperature dependent manner at the mid-pupal stage.

(A–G′) Confocal micrographs each showing a single ommatidium from the indicated genotypes. Phalloidin (green) marks Actin and is concentrated in rhabdomeres; Eys is shown in red. The dotted shapes mark the outline of a single photoreceptor cell body in each micrograph. The scale bar in A applies to A–G′ and is 5 µm. (A,A′) A wild-type ommatidium at 55% PD raised at 18°C. Note that Eys is primarily localized to the IRS. (B,B′) A rumi−/− ommatidium at 55% PD raised at 18°C. Note the decreased level of Eys in the IRS and its accumulation in the cell body. (C,C′) A wild-type ommatidium at 95% PD raised at 18°C. (D,D′) A rumi−/− ommatidium at 95% PD raised at 18°C. Note the increased amount of Eys in the IRS at this stage and disappearance of Eys from the photoreceptor cell bodies compared to B. White arrowheads mark points of rhabdomere attachment and gaps in Eys. (E,E′) A single ommatidium from a wild-type animal at 55% PD shifted to 30°C during IRS formation. (F–G′) Ommatidia from rumi−/− animals at 55% PD shifted to 30°C during IRS formation show severe Eys accumulation in the cell body, with either a complete lack of Eys in the IRS (F,F′) or a thin line of Eys in the IRS (G,G′). (H,I) Electron micrographs showing wild-type (H) and rumi−/− (I) ommatidia from 75% PD animals shifted to 30°C during IRS formation. The scale bar in I applies to H and I and is 2 µm. As shown above, rumi mutants raised at 18°C show rhabdomere attachment and a significantly decreased IRS size in the mid-pupal stage (Figure 1K). However, in rumi−/− adults, even though the rhabdomere attachments persist, the IRS in the center of the ommatidia looks similar to that in control ommatidia (Figure 1A–E), suggesting that enough Eys is secreted in later pupal stages to expand the IRS. To test this notion, we examined Eys expression in wild-type and rumi null animals at 95% PD. In wild-type animals, Eys fills the IRS in an uninterrupted manner and cannot be seen in the cell body (Figure 5C–C′). In rumi mutants, Eys is properly localized to the IRS at levels similar to that found in wild-type IRS and is not visible in the cell body (Figure 5D and 5D′). However, multiple gaps in the Eys expression domain are seen in the IRS, coinciding with rhabdomere attachments (Figure 5D and 5D′, white arrowheads). These data suggest that the rhabdomere attachments in rumi mutants result from decreased levels of Eys in the IRS in a critical period during the mid-pupal stage and that these attachments are not resolved later in pupal development despite continued secretion of Eys.

Since the loss of Notch signaling in rumi mutants is temperature-sensitive [12], [14], [15], we next examined whether the IRS defect observed in rumi animals becomes worse at higher temperatures. To bypass the larval lethality and photoreceptor specification defects of rumi mutants at 30°C, we kept rumi mutant and control animals at 18°C until the end of the third instar stage and shifted them to 30°C at zero hours after puparium formation (APF) so that they were kept at high temperature at mid-pupal stage, when eys expression starts [5]. However, these animals died by mid-pupal stage, precluding the study of Eys secretion and IRS formation. Therefore, we modified our temperature shift regimen by transferring rumi−/− and control animals to 25°C at zero h APF, shifted them to 30°C at 24 h APF and kept them at this temperature until 55%–75% pupal development, when we dissected them for staining or TEM. The patterns of Phalloidin and Eys staining in control animals looked similar to those raised at 18°C (Figure 5E and 5E′). In contrast, rumi mutants either lacked Eys in the IRS (Figure 5F and 5F′) or had small Eys-containing regions (Figure 5G and 5G′). Most rumi mutant ommatidia showed high levels of Eys in the photoreceptor cells (Figure 5F–G′). TEM on rumi−/− animals reared under the above mentioned conditions showed multiple sites of rhabdomere attachment and a small IRS at 75% PD compared to control animals raised under the same conditions (Figure 5H and 5I). These observations indicate that in rumi mutants grown at higher temperatures, a higher fraction of Eys remains inside the cell and the level of Eys in the IRS is further reduced.

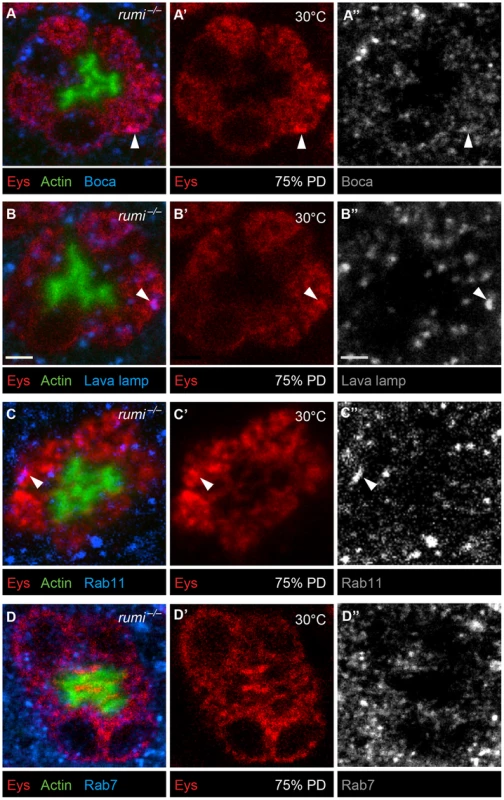

To examine whether Eys accumulates in a specific subcellular compartment in rumi mutant photoreceptor cells, we performed colocalization studies between Eys and markers of ER (Figure 6A–A″), Golgi (Figure 6B–B″), recycling endosome (Figure 6C–C″), and the late endosome (Figure 6D–D″) in rumi null animals shifted to 25°C at zero h APF and later to 30°C at 24 h APF as explained above. Eys was transported to all cellular compartments examined, as shown by occasional colocalization with each marker (Figure 6A–D″, white arrowheads), indicating that Eys trafficking is not blocked at a single step in the secretion pathway but is likely slowed down through the secretory pathway, causing it to accumulate in the cell body as it travels to the membrane.

Fig. 6. Eys does not accumulate in a single subcellular compartment in rumi−/− photoreceptors raised at 30°C.

Confocal micrographs from 75% PD rumi−/− ommatidia colabeled with Eys and the ER marker Boca (A–A″), the Golgi marker Lava lamp (B–B″), the recycling endosomal marker Rab11 (C–C″), and the late endosomal marker Rab7 (D–D″). White arrowheads mark colocalization between Eys and the respective subcellular compartment. Eys only shows occasional colocalization with each marker, strongly suggesting that Eys does not accumulate in a single compartment. Worsening of the IRS defect and further decrease in the extracellular levels of Eys in rumi mutant animals raised at higher temperature suggest that in the absence of Rumi, Eys is misfolded. To assess the effects of loss of Rumi on Eys protein levels at low and high temperatures, we performed Western blots on head extracts from 80% PD wild-type and rumi−/− animals. When raised at 18°C throughout development, wild-type and rumi−/− pupae did not show a significant difference in the level of Eys (Figure 7A, left panel, P = 0.57). However, when the animals were raised at 18°C until mid-pupal stage and shifted to 30°C during IRS formation, there was a significant decrease in the level of Eys in rumi−/− pupal heads (Figure 7A, right panel, P<0.05). These data support the notion that loss of Rumi decreases the ability of Eys to fold properly and to be secreted at a normal rate. The data also suggest that at higher temperatures, misfolding results in degradation of Eys and worsening of IRS defects in rumi mutant animals.

Fig. 7. rumi−/− animals show a temperature-dependent decrease in Eys levels and a dosage-sensitive genetic interaction with an ER chaperone.

(A) Western blots showing Eys levels in rumi−/− and y w heads grown at 18°C (left) and 30°C (right). There is a statistically significant decrease in Eys levels in rumi−/− heads raised at 30°C (P<0.05; lower panel). (B,C) Hsc70-3+/−; rumi−/− ommatidia show an enhancement of the rumi−/− phenotype. (B) Electron micrograph showing a single ommatidium from an Hsc70-3+/−; rumi+/− control animal. (C) Electron micrograph showing an Hsc70-3+/−; rumi−/− ommatidium. Frequently, all rhabdomeres but one are attached. (D) Quantification of average individual rhabdomere number per ommatidium for the indicated genotypes. *P<0.0001. (E) Levels of Hsc70-3, which is induced upon UPR, do not change between rumi−/− and y w animals raised at different temperatures. Top panel: western blot showing Hsc70-3 levels and Tubulin loading control. Bottom panel: ratio of Hsc70-3/Tubulin levels, which do not change between genotypes. NS, not significant. If rhabdomere attachments observed in rumi mutants result from Eys misfolding, decreasing the level of chaperone proteins might enhance this phenotype. To test this hypothesis, we examined whether removing one copy of the ER chaperone Hsc70-3 (BiP) affects rhabdomere attachment in rumi−/− animals. As shown in Figure 7B, animals double heterozygous for a lethal P-element inserted in the coding region of Hsc70-3 (Hsc70-3G0102) and rumi do not exhibit any rhabdomere attachment. However, Hsc70-3G0102/+; rumi−/− animals raised at 18°C show an enhancement of the rhabdomere attachment phenotype observed in rumi−/− animals raised at the same temperature (Figure 7C; compare to Figure 1). The average number of separate rhabdomeres in Hsc70-3G0102/+; rumi−/− animals is significantly different from rumi−/− animals (Figure 7D, 2.85±0.11 vs. 4.11±0.08, P<0.0001). This observation further supports the conclusion that Eys is misfolded in rumi mutants. We next asked whether loss of Rumi triggers the unfolded protein response (UPR) in the pupal eye. One of the hallmarks of the UPR is the induction of chaperones, including Hsc70-3 [27]. Western blotting using anti-Hsc70-3 antibody did not show an increase in the level of Hsc70-3 expression in rumi mutants raised at 18°C or 30°C compared to control animals (Figure 7E). This indicates that UPR is not induced in the pupal eyes upon loss of Rumi, in agreement with a previous report on lack of UPR induction in rumi−/− clones in wing imaginal discs raised at 28°C despite accumulation of the Notch protein [12].

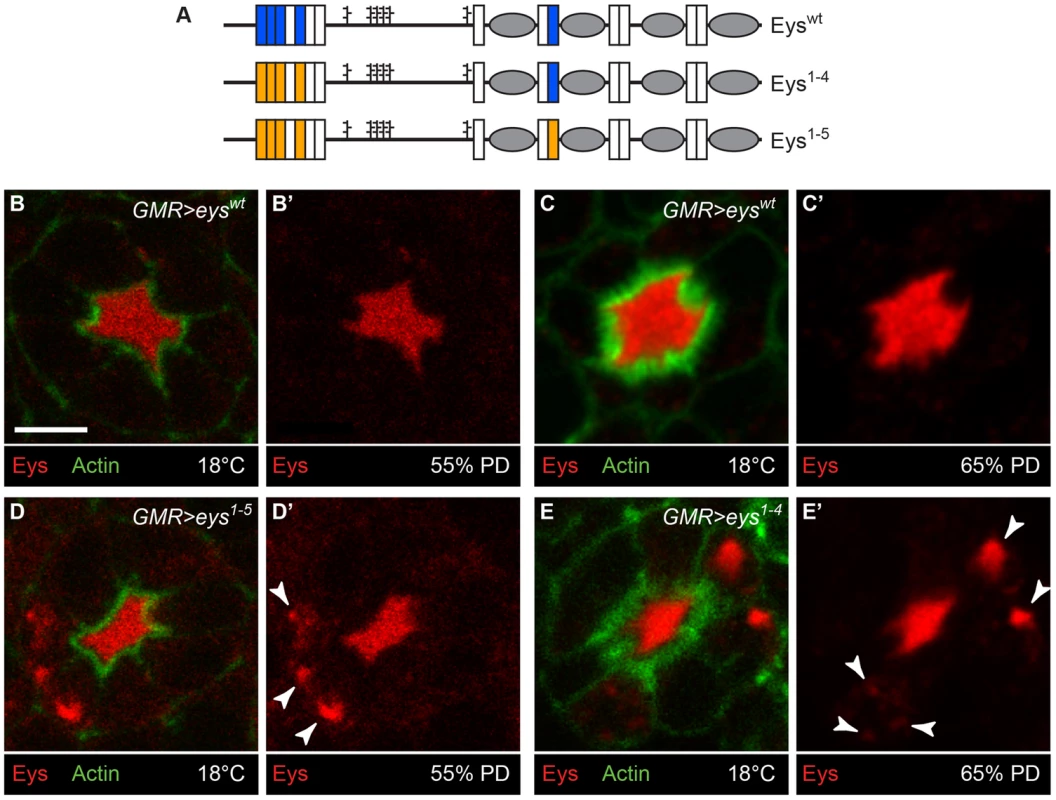

Mutations in Eys O-glucosylation sites result in its intracellular accumulation

If loss of the Poglut activity results in intracellular accumulation of Eys in the mid-pupal stage, mutating the Rumi target sites on Eys should affect its trafficking as well. To test this, we generated UAS-attB transgenes capable of overexpressing wild-type Eys (Eyswt) or Eys with serine-to-alanine mutations in four (Eys1-4) or in all five Rumi target sites (Eys1-5) (Figure 8A). To minimize the expression variability associated with random insertion of transgenes, we used ΦC31 transgenesis and integrated all three constructs in the same docking site (VK31) in the fly genome [28], [29]. We used GMR-GAL4 to overexpress wild-type and mutant Eys in the developing photoreceptors and kept the animals at 18°C to avoid the very high levels of GAL4-driven transgene expression at high temperatures. In animals overexpressing wild-type Eys, the IRS is expanded and the majority of the Eys is within the IRS, although low levels of Eys are seen in photoreceptor cells (Figure 8B–C′). Overexpression of Eys1-4 and Eys1-5 also expands the IRS (Figure 8D–E′, compare to Figure 5). However, unlike the wild-type protein, O-glucose mutant versions of Eys protein accumulate in the photoreceptor cells (Figure 8D–E′, white arrowheads). These data support a role for O-glucose residues in the proper folding and trafficking of Eys.

Fig. 8. Loss of O-glucose on Eys results in its intracellular accumulation.

(A) Schematic of Eyswt, Eys1-4, in which four out of five Rumi target sites are mutated, and Eys1-5, in which all Rumi target sites are mutated. (B–E′) Overexpression of Eys1-5 (D,D′) and Eys1-4 (E,E′), but not Eyswt (B–C′), results in intracellular Eys accumulation (arrowheads). The GMR-GAL4 driver was used and all animals were raised at 18°C. Note that the GMR>eyswt animal shown in (B,B′) and the GMR>eys1-5 animal (D,D′) are younger than the GMR>eyswt animal shown in (C,C′) and the GMR>eys1-4 animal (E,E′). Scale bar: 5 µm. Discussion

We have previously shown that the extracellular domains of Drosophila and mammalian Notch proteins are efficiently O-glucosylated, and have provided strong evidence that Rumi/POGLUT1 is the only protein O-glucosyltransferase capable of adding O-glucose to EGF repeats in animals [12], [13], [16], [18], [30]. The data presented here indicate that Drosophila Crb and Eys also harbor O-glucose residues, yet the impact of loss of Rumi and loss of O-glucose from these three target proteins, which harbor the highest number of Rumi target sites among all Drosophila proteins, is not equivalent. Loss of Rumi and mutations in Rumi target sites in a Notch genomic transgene both result in a temperature-dependent loss of Notch signaling [12], [14], indicating that the Notch protein becomes sensitive to temperature alterations in the absence of O-glucose. Although the Notch loss-of-function phenotypes in rumi mutants raised at 18°C are mild and limited to certain contexts, raising animals homozygous for rumi or harboring rumi mitotic clones at 28–30°C phenocopies Notch-null phenotypes [12], [15], [17], indicating that O-glucose is indispensable for the function of Drosophila Notch at the restrictive temperature. At a functional level, loss of Rumi affects Eys similarly, with a moderate rhabdomere attachment phenotype at 18°C which becomes more severe when rumi animals are raised at 30°C during the IRS formation. However, even when raised at 30°C, rumi does not phenocopy an eys-null phenotype in the eye, as rhabdomeres show some degree of separation in the mid-pupal stage. The function of Crb, in contrast, does not seem to be significantly affected by loss of O-glucose, as flies homozygous for a mutant allele of crb which contains no intact Rumi consensus sequences are viable and fertile, and do not exhibit any obvious phenotypes in rhabdomere morphogenesis. The divergent effects of O-glucose on the function of these proteins does not seem to be correlated with the number of Rumi target sites or the overall structure of these proteins, as Notch and Crb are transmembrane proteins but Eys is secreted, Crb and Eys both have a combination of EGF repeats and Laminin G domains but Notch does not have Laminin G domains, and Crb has a higher number of Rumi target sites (seven) compared to Eys (five). In summary, our data indicate that although the C1XSX(P/A)C2 motif is highly predictive for the addition of O-glucose to EGF repeats of Drosophila proteins, the functional importance of O-glucose depends on additional parameters beyond the number of O-glucose sites and the overall domain structure of a given target protein.

In rumi mutant ommatidia, a significant amount of Eys remains inside the photoreceptor cells, while the extracellular levels of Eys in the IRS decrease. At the restrictive temperature, these phenotypes are enhanced and the total level of Eys in rumi mutant heads is significantly decreased. Moreover, removing one copy of an important ER chaperone enhances the rhabdomere attachment phenotype in rumi mutants. Finally, animals homozygous for the catalytically-inactive allele rumi79 also show rhabdomere attachment, and mutating the O-glucose sites of Eys results in its intracellular accumulation. Together, these observations strongly suggest that loss of O-glucosylation results in Eys misfolding and a decrease in its extracellular levels. In contrast, despite the almost complete loss of Notch signaling in rumi clones raised at 28–30°C, surface expression of Notch is not decreased upon loss of Rumi; indeed, Notch accumulates inside and at the surface of rumi mutant epithelial cells raised at the restrictive temperature [12]. Moreover, cell-based and genetic experiments suggest that in the absence of Rumi, Notch is able to bind ligands at the cell surface but fails to be cleaved properly by the ADAM10 metalloproteinase Kuzbanian [12], [14]. Therefore, although these reports cannot rule out a redundant role for O-glucose in promoting the cell surface expression of Notch, they indicate that O-glucose is required for Notch signaling independently of its exocytic trafficking. Nevertheless, the temperature-dependent enhancement of loss of Notch signaling and Notch accumulation in rumi mutants [12], [14] suggests that folding of Notch might also be affected by the loss of O-glucose. Similarly, the increase in the number of Crb+ puncta observed in rumi−/− photoreceptors raised at 25°C suggests that although the function of Drosophila Crb does not depend on O-glucosylation, loss of O-glucose affects Crb trafficking. Therefore, while we cannot rule out that O-glucosylation affects each of these targets differently at molecular and cell biological levels, we favor a scenario in which the folding of all three targets is affected by loss of O-glucose. In this scenario, the degree of functional defects observed for each target and the cellular compartment where the defect is observed varies depending on the extent of misfolding, the sensitivity of the target protein to lack of O-glucose and the cellular context where the target operates. It is intriguing to note that Rumi/POGLUT1 only glucosylates properly folded EGF repeats in vitro [31], suggesting that Rumi/POGLUT1 may exert its effects on folding at the level of individual EGF repeats.

Analysis of rhabdomere separation and IRS size in mid-pupal and late pupal/adult rumi−/− animals raised at 18°C suggests two temporally distinct steps for the function of Eys during IRS formation. In the early stages of IRS formation, some of the rhabdomeres in each ommatidium fail to separate from each other, and the mutant IRS is significantly smaller than control IRS. In late pupal stages, the level of Eys in the IRS of rumi−/− ommatidia is comparable to that in control ommatidia, in agreement with the more or less normal IRS size observed in adult rumi ommatidia. Nevertheless, rhabdomere attachments are not resolved. These observations suggest that Eys generates the IRS in two steps. At ∼45–55% PD, Eys secretion is required to sever the attachments among the rhabdomeres in each ommatidium (step 1), likely by opposing the adhesive forces mediated by Chaoptin [6]. Rhabdomere separation in turn generates conduits between stalk membranes—where Eys is secreted [5] —and the central IRS, and thereby allows Eys to increase the IRS size after rhabdomeres are separated (step 2). We propose that in rumi mutants, the Eys protein fails to fold properly and as a result, a significant fraction of Eys remains inside the cell instead of being secreted into the extracellular space. Therefore, at the mid-pupal stage Eys fails to fully separate the rhabdomeres from one another. Once the critical time window between 45–55% PD (step 1) passes, continued Eys secretion in step 2 (IRS expansion) cannot separate rhabdomeres anymore. However, since in each rumi ommatidium some rhabdomeres separate from one another, Eys can reach the central IRS and can gradually increase the IRS size. This two-step model of rhabdomere separation and IRS expansion is further supported by the observation that overexpression of Eys in an eys null background after 65% PD fails to separate the rhabdomeres [6].

Lack of photoreceptor abnormalities in crb mutants with no intact Rumi target sites was somewhat surprising, given that Crb has the second highest number of O-glucosylation motifs in all fly proteins and that multiple EGF repeats in human CRB1 and CRB2 contain the Rumi consensus sequence. Our data indicate that O-glucosylation of Crb is not required for viability, fertility and photoreceptor morphogenesis in flies, at least in a laboratory setting. The Crb extracellular domain is dispensable for proper apical-basal polarity in embryos [32], but is required in other contexts, such as stalk membrane formation [11], regulation of the head size [24], prevention of light-induced photoreceptor degeneration [21] and invagination of the salivary gland placode in embryos [33]. While the stalk membrane formation is not impaired upon mutating all Crb O-glucose sites, it remains to be determined whether O-glucosylation of Crb is required for the regulation of other processes regulated by the Crb extracellular domain, and whether O-glucosylation of mammalian CRB proteins is required for their function.

Although a number of mammalian species including mice, rats, guinea pigs and sheep have lost Eys during evolution [34], humans have an Eys homolog (EYS), which shows an overall protein domain organization similar to the fly Eys (Figure 4) [35]. Transgenic expression of human EYS in a Drosophila eys null background produces pockets of IRS, presumably at the location of secretion, but fails to rescue the rhabdomere attachment phenotype [9]. However, when human EYS is coexpressed in eys−/− animals with a human homolog of the Drosophila Prom called PROM1, some rhabdomeres separate from their neighbors [9]. Since binding between Drosophila Eys and Prom is important for IRS formation [6], these rescue experiments highlight the evolutionary conservation of the Eys-Prom interaction in the visual system. Of note, mutations in human EYS and PROM1 cause several forms of retinal degeneration including autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa, rod-cone dystrophies and cone-rod dystrophy [34]–[43]. Human EYS contains seven target sites for O-glucosylation, 4–5 of which are clustered similar to the Rumi target sites in EGF1-5 of Drosophila Eys. Therefore, O-glucosylation might play an important role in the function of the human EYS.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila strains and genetics

The following strains were used in this study: 1) Canton-S, 2) y w, 3) w; nocSco/CyO; TM3, Sb1/TM6, Tb1, 4) y w; D/TM6, Tb1, 5) N55e11/FM7c, 6) y1 w67c23 P{Crey}1b; D*/TM3, Sb1, 7) y1 M{vas-int.Dm}ZH-2A w*; VK31, 8) y1 M{vas-int.Dm}ZH-2A w*; VK22, 9) w67 c23 P{lacW}Hsc70-3G0102/FM7c, 10) GMR-GAL4 (on 2) (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center), 11) GMR-GAL4 (on 3) [44], 12) eys734 [5], 13) P{rumigt-FLAG} (rumi rescue transgene), 14) y w; FRT82B rumi79/TM6, Tb1, 15) y w; FRT82B rumiΔ26/TM6, Tb1 [12], 16) y w; PBac{Ngt-4-35}attVK22 [14], 17) eys734/CyO; FRT82B rumiΔ26/TM6, Tb1, 18) y w; crb1-7::HA-A (crb1-7-HA), 19) UAS-attB-eyswt-VK31, 20) UAS-attB-eys1-4-VK31, 21) UAS-attB-eys1-5-VK31, 22) UAS-attB-rumiwt-FLAG-VK22, 23) UAS-attB-rumi79-FLAG-VK22 (this study), 24) y w; crbwt::HA-A (crbwt-HA) [25], 25) crb11A22/TM6, Tb1 [10].

All rumi mutant crosses were raised at 18°C to minimize the temperature-dependent defects in Notch signaling unless otherwise specified. To obtain N55e11/Y; PBac{Ngt-4-35}attVK22/+ animals, N55e11/FM7c females were crossed to y w/Y; PBac{Ngt-4-35}attVK22 males and the male progeny were selected based on the absence of the FM7 bar eye phenotype.

To remove one copy of Hsc70-3 in rumi−/− animals, w67 c23 P{lacW}Hsc70-3G0102/FM7c females were first crossed to y w; FRT82B rumiΔ26/TM6, Tb1 males. The w67 c23 P{lacW}Hsc70-3G0102/y w; FRT82B rumiΔ26/+ female progeny from this cross were backcrossed to y w; FRT82B rumiΔ26/TM6, Tb1 males. w67 c23 P{lacW}Hsc70-3G0102/y w; FRT82B rumiΔ26/FRT82B rumiΔ26 progeny were selected based on the eye color from the Hsc70-3 allele and the rumi mutant bristle phenotype [14] and used for TEM analysis.

O-Glucose site mapping on Drosophila Crb and Eys fragments expressed in S2 cells

A construct encoding EGF1-5 from Drosophila Eys (harboring four out of the five Rumi target sites of Eys) was synthesized (Genewiz, Inc.). EGF12-17 from Drosophila Crb (harboring five out of the seven Rumi targets sites of Crb) was amplified using region-specific primers from genomic DNA extracted from flies carrying a UAS-crb-full-length transgene [20]. The genomic DNA was obtained using a DNA purification kit from Promega. The Eys fragment was cloned in frame to an N-terminal signal peptide from Drosophila Acetylcholine esterase and C-terminal V5 and 6x-Histidine tags in the pMT/V5-HisB-ACE vector [12]. The Crb fragment was cloned into a pMT/BiP/3xFLAG vector using EcoRI and XbaI [45]. Eys-EGF1-5-V5-His and Crb-EGF12-17-3xFLAG were expressed in Drosophila S2 cells, purified from medium by Nickel column or anti-FLAG resin, respectively, reduced and alkylated, and subjected to in-gel protease digests as described [46], [47] with minor modifications. O-Glucose modified glycopeptides were identified by neutral loss of the glycans during collision-induced dissociation (CID) using nano-LC-MS/MS as described [13].

Dissections, staining, processing, image acquisition and quantification

For dissection at 55% and 65% pupal development, animals were selected at the white prepupal stage and aged for 4.5 days (55%) and 5.5 days (65%) at 18°C. For animals raised at higher temperatures, the white prepupae were placed at 25°C at zero hours APF for 1 day and subsequently placed at 30°C until 55% or 75% PD for dissection. The pupal case was removed and heads were pierced to allow proper fixation. Corneas were removed from the eyes in PBS. Tissues were fixed using 4% formaldehyde for 30–40 minutes, and then washed in 0.3–0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS. Blocking and antibody incubations were performed in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and 5% Serum (Donkey or Goat). The following antibodies were used: mouse anti-Eys (21A6) 1∶250 and mouse anti-ELAV (9F8A9) 1∶200 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), guinea pig anti-Eys 1∶1000 [5], guinea pig anti-Boca 1∶1000 [48], rat anti-Crb 1∶500 [11], rabbit anti-Lava lamp 1∶2000 [49], rabbit anti-Rab11 1∶1000 [50], Rabbit anti-Rab7 1∶100 [51], mouse anti-Rab11 1∶100 (BD Biosciences), guinea pig anti-Senseless 1∶2000 [52], goat anti-mouse-Cy3 1∶500, goat anti-mouse-Cy5 1∶500, donkey anti-mouse-Dylight649 1∶500, donkey anti-mouse-Cy3 1∶500, donkey anti-rabbit-Cy3 1∶500, donkey anti-guinea pig-Dylight649 1∶500 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Phalloidin Alexa488 conjugated 1∶500 (Life Technologies) was used to visualize rhabdomeres. Confocal images were taken with either a Leica TCS-SP5 microscope with an HCX-PL-APO oil 63x, NA 1.25 objective and an HCX-PL-APO 20x, 0.7 NA objective with a PMT SP confocal detector, or a TCS-SP8 microscope with an HC-PL-APO glycerol 63x, NA 1.3 objective and HyD SP GaAsp detector. All images were acquired using Leica LAS-SP software. Amira 5.2.2 and Adobe Photoshop CS4 were used for processing and figures were assembled in Adobe Illustrator CS5.1.

To quantify IRS size, the electron micrographs were opened using “Fiji is just ImageJ” open source image processing software. The scale was set by tracing the scale bar in the image using the line tool and using the “set scale” function. The IRS was traced using the freehand selection tool and the area was measured using the “measure” function.

To quantify total pixel intensity, the Amira 5.2.2 image processing software was used. A single ommatidium was cropped, which was done twice for each image to obtain data from 2 different ommatidia per animal. The desired channel for quantification was labeled with the “label field” function, and the “segmentation editor” was opened. The IRS was traced using the lasso freehand tool, placed in a separate “material”, and the rest of the pixels in the channel were selected using the threshold tool and placed in a separate “material”. The same threshold was used for all ommatidia. In the “object pool” module, the total pixel intensities for IRS and the rest of the ommatidium were obtained using the “material statistics” option.

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted by lysing the heads in RIPA buffer (Boston BioProducts) containing a dissolved protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche Diagnostics). Approximately 10 µL RIPA buffer was used per fly head. The following antibodies were used: guinea pig anti-Hsc70-3 1∶5000 [27], guinea pig anti-Eys 1∶10000 [5], mouse anti-FLAG 1∶1000 (M2, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-Tubulin 1∶1000 (Santa Cruz Biotech), goat anti-guinea pig-HRP 1∶5000 and goat anti-mouse-HRP 1∶5000 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Western blots were developed using Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrates (Thermo Scientific). The bands were detected and quantified using an ImageQuant LAS 4000 system and ImageQuant TL software, respectively, from GE Healthcare. At least two independent immunoblots were performed for each experiment.

Transmission electron microscopy

To process flies using transmission electron microscopy, heads were dissected and fixed overnight at 4°C in paraformaldehyde, glutaraldehyde and cacodylic acid and processed as previously described [53]. Briefly, after fixation, heads were post fixed with 1–2% OsO4, dehydrated with ethanol and propylene oxide, and then embedded in Embed-812 resin. Thin sections (∼50 nm thick) were stained with 1–2% uranyl acetate as the negative stain and then stained with Reynold's lead citrate. Images were obtained using three different transmission electron microscopes: 1) Hitachi H-7500 with a Gatan US100 camera: images were captured using Digital Micrograph, v1.82.366 software; 2) JEOL 1230 with a Gatan Ultrascan 1000 camera: images were captured with Gatan Digital Micrograph software; 3) JEOL JEM 1010 with an AMT XR-16 camera: images were captured using AMT Image Capture Engine V602. All images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS4 and figures were assembled in Adobe Illustrator CS5.1.

Generation of the knock-in and transgenic animals

To generate the crb1-7::HA-A knock-in allele (crb1-7-HA), a crb mutant founder line was used in which 10 kb of the crb locus harboring most of the coding region is replaced with an attP and a loxP site [25]. Multiple rounds of end overlap PCR were used to introduce serine-to-alanine mutations in all seven Rumi target sites of Crb in the pGE-attBGMR-crbwt::HA-A targeting vector [25] to generate the pGE-attBGMR-crb1-7::HA-A targeting construct. ΦC31-mediated integration was used to introduce the crb1-7::HA-A fragment into the crb locus of the crb mutant founder line. A Cre-expressing transgene [54] was used to remove the GMR-hsp::white and the remaining vector sequences from the knock-in allele and to obtain the white− allele crb1-7::HA-A used in our study. Genomic PCR with multiple primer pairs in the region was performed to confirm correct integration and Cre-mediated recombination, as described previously [25]. Primer sequences are available upon request.

To generate the wild-type and mutant eys transgenes, the full length eys cDNA was retrieved from the pUAST-eys construct [6] using restriction digestion and cloned into the pUASTattB vector [28], resulting in pUASTattB-eyswt. To generate the mutant eys transgenes, a 603-bp cDNA fragment containing EGF1-5 of Eys with serine-to-alanine mutations in the four target sites in this region (EGF1-3 and EGF5) was synthesized (Genewiz, Inc.). The wild-type EGF1-5 region in pUASTattB-eyswt construct was replaced with the synthesized mutant version using two rounds of end-overlap PCR [55] with three overlapping fragments. The resulting 1.2-kb fragment containing the first four mutant Rumi target sites was placed in pUASTattB-eyswt by using BglII and SacII restriction enzymes to generate pUASTattB-eys1-4. To mutate the fifth (last) Rumi target site in eys, a 4-kb fragment of the eys cDNA containing the target site (EGF9) and flanked by NdeI and KpnI restriction sites was PCR amplified using Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). The PCR product was cloned into pSC-B using the Strataclone blunt PCR cloning kit (Agilent Technologies) to generate pSC-B-Eys-EGF9. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using complementary primers and Phusion DNA polymerase to introduce the serine-to-alanine mutation. The wild-type 4-kb fragment from pUASTattB-eys1-4 was replaced with the mutant version by using NdeI and KpnI to generate pUASTattB-eys1-5. All three constructs were integrated into the VK31 docking site using standard methods [28], [29]. Correct integration was confirmed by PCR.

To generate wild-type and mutant rumi transgenes, FLAG-tagged versions of rumiwt and rumi79 (G189E) ORF were excised from pUAST-rumiwt-FLAG and pUAST-rumi79-FLAG [12] by using EcoRI-KpnI double digestion and were cloned into the pUAST-attB vector [28]. After verification by sequencing, the constructs were integrated into the VK22 docking site using standard methods and verified by PCR [28], [29].

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. To compare the number of rhabdomere clusters per ommatidium, ANOVA with Scheffé or Tukey multiple comparisons or t-test was performed. To compare the IRS size between wild-type and rumi ommatidia at 65% PD, unpaired t-test was used.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BorstA (2009) Drosophila's view on insect vision. Curr Biol 19: R36–47.

2. NilssonDE (1990) From cornea to retinal image in invertebrate eyes. Trends Neurosci 13 : 55–64.

3. ClandininTR, ZipurskySL (2000) Afferent growth cone interactions control synaptic specificity in the Drosophila visual system. Neuron 28 : 427–436.

4. KirschfeldK (1967) [The projection of the optical environment on the screen of the rhabdomere in the compound eye of the Musca] (Original in German). Exp Brain Res 3 : 248–270.

5. HusainN, PellikkaM, HongH, KlimentovaT, ChoeKM, et al. (2006) The agrin/perlecan-related protein eyes shut is essential for epithelial lumen formation in the Drosophila retina. Dev Cell 11 : 483–493.

6. ZelhofAC, HardyRW, BeckerA, ZukerCS (2006) Transforming the architecture of compound eyes. Nature 443 : 696–699.

7. CoelhoDS, CairraoF, ZengX, PiresE, CoelhoAV, et al. (2013) Xbp1-independent Ire1 signaling is required for photoreceptor differentiation and rhabdomere morphogenesis in Drosophila. Cell Rep 5 : 791–801.

8. GurudevN, YuanM, KnustE (2014) chaoptin, prominin, eyes shut and crumbs form a genetic network controlling the apical compartment of Drosophila photoreceptor cells. Biol Open 3 : 332–341.

9. NieJ, MahatoS, MustillW, TippingC, BhattacharyaSS, et al. (2012) Cross species analysis of Prominin reveals a conserved cellular role in invertebrate and vertebrate photoreceptor cells. Dev Biol 371 : 312–320.

10. TepassU, TheresC, KnustE (1990) crumbs encodes an EGF-like protein expressed on apical membranes of Drosophila epithelial cells and required for organization of epithelia. Cell 61 : 787–799.

11. PellikkaM, TanentzapfG, PintoM, SmithC, McGladeCJ, et al. (2002) Crumbs, the Drosophila homologue of human CRB1/RP12, is essential for photoreceptor morphogenesis. Nature 416 : 143–149.

12. AcarM, Jafar-NejadH, TakeuchiH, RajanA, IbraniD, et al. (2008) Rumi is a CAP10 domain glycosyltransferase that modifies Notch and is required for Notch signaling. Cell 132 : 247–258.

13. RanaNA, Nita-LazarA, TakeuchiH, KakudaS, LutherKB, et al. (2011) O-glucose trisaccharide is present at high but variable stoichiometry at multiple sites on mouse Notch1. J Biol Chem 286 : 31623–31637.

14. LeonardiJ, Fernandez-ValdiviaR, LiYD, SimcoxAA, Jafar-NejadH (2011) Multiple O-glucosylation sites on Notch function as a buffer against temperature-dependent loss of signaling. Development 138 : 3569–3578.

15. PerdigotoCN, SchweisguthF, BardinAJ (2011) Distinct levels of Notch activity for commitment and terminal differentiation of stem cells in the adult fly intestine. Development 138 : 4585–4595.

16. Fernandez-ValdiviaR, TakeuchiH, SamarghandiA, LopezM, LeonardiJ, et al. (2011) Regulation of the mammalian Notch signaling and embryonic development by the protein O-glucosyltransferase Rumi. Development 138 : 1925–1934.

17. TakeuchiH, Fernandez-ValdiviaRC, CaswellDS, Nita-LazarA, RanaNA, et al. (2011) Rumi functions as both a protein O-glucosyltransferase and a protein O-xylosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 16600–16605.

18. LeeTV, SethiMK, LeonardiL, RanaNA, BuettnerFF, et al. (2013) Negative Regulation of Notch Signaling by Xylose. PLoS Genet 9: e1003547.

19. LongleyRLJr, ReadyDF (1995) Integrins and the development of three-dimensional structure in the Drosophila compound eye. Dev Biol 171 : 415–433.

20. IzaddoostS, NamSC, BhatMA, BellenHJ, ChoiKW (2002) Drosophila Crumbs is a positional cue in photoreceptor adherens junctions and rhabdomeres. Nature 416 : 178–183.

21. JohnsonK, GraweF, GrzeschikN, KnustE (2002) Drosophila crumbs is required to inhibit light-induced photoreceptor degeneration. Curr Biol 12 : 1675–1680.

22. ChenCL, GajewskiKM, HamaratogluF, BossuytW, Sansores-GarciaL, et al. (2010) The apical-basal cell polarity determinant Crumbs regulates Hippo signaling in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 15810–15815.

23. LingC, ZhengY, YinF, YuJ, HuangJ, et al. (2010) The apical transmembrane protein Crumbs functions as a tumor suppressor that regulates Hippo signaling by binding to Expanded. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 10532–10537.

24. RichardsonEC, PichaudF (2010) Crumbs is required to achieve proper organ size control during Drosophila head development. Development 137 : 641–650.

25. HuangJ, ZhouW, DongW, WatsonAM, HongY (2009) From the Cover: Directed, efficient, and versatile modifications of the Drosophila genome by genomic engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 8284–8289.

26. RobinsonBS, HuangJ, HongY, MobergKH (2010) Crumbs regulates Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling in Drosophila via the FERM-domain protein Expanded. Curr Biol 20 : 582–590.

27. RyooHD, DomingosPM, KangMJ, StellerH (2007) Unfolded protein response in a Drosophila model for retinal degeneration. Embo J 26 : 242–252.

28. BischofJ, MaedaRK, HedigerM, KarchF, BaslerK (2007) An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 3312–3317.

29. VenkenKJ, HeY, HoskinsRA, BellenHJ (2006) P[acman]: a BAC transgenic platform for targeted insertion of large DNA fragments in D. melanogaster. Science 314 : 1747–1751.

30. MoloneyDJ, ShairLH, LuFM, XiaJ, LockeR, et al. (2000) Mammalian Notch1 is modified with two unusual forms of O-linked glycosylation found on epidermal growth factor-like modules. J Biol Chem 275 : 9604–9611.

31. TakeuchiH, KanthariaJ, SethiMK, BakkerH, HaltiwangerRS (2012) Site-specific O-glucosylation of the epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) repeats of notch: efficiency of glycosylation is affected by proper folding and amino acid sequence of individual EGF repeats. J Biol Chem 287 : 33934–33944.

32. WodarzA, HinzU, EngelbertM, KnustE (1995) Expression of crumbs confers apical character on plasma membrane domains of ectodermal epithelia of Drosophila. Cell 82 : 67–76.

33. RoperK (2012) Anisotropy of Crumbs and aPKC drives myosin cable assembly during tube formation. Developmental cell 23 : 939–953.

34. Abd El-AzizMM, BarraganI, O'DriscollCA, GoodstadtL, PrigmoreE, et al. (2008) EYS, encoding an ortholog of Drosophila spacemaker, is mutated in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet 40 : 1285–1287.

35. CollinRW, LittinkKW, KleveringBJ, van den BornLI, KoenekoopRK, et al. (2008) Identification of a 2 Mb human ortholog of Drosophila eyes shut/spacemaker that is mutated in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet 83 : 594–603.

36. IwanamiM, OshikawaM, NishidaT, NakadomariS, KatoS (2012) High prevalence of mutations in the EYS gene in Japanese patients with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53 : 1033–1040.

37. LittinkKW, van den BornLI, KoenekoopRK, CollinRW, ZonneveldMN, et al. (2010) Mutations in the EYS gene account for approximately 5% of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa and cause a fairly homogeneous phenotype. Ophthalmology 117 : 2026–2027, 2026-2033, 2033, e2021-2027.

38. AudoI, SahelJA, Mohand-SaidS, LancelotME, AntonioA, et al. (2010) EYS is a major gene for rod-cone dystrophies in France. Hum Mutat 31: E1406–1435.

39. KatagiriS, AkahoriM, HayashiT, YoshitakeK, GekkaT, et al. (2014) Autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy associated with compound heterozygous mutations in the EYS gene. Doc Ophthalmol 128 : 211–217.

40. PrasE, AbuA, RotenstreichY, AvniI, ReishO, et al. (2009) Cone-rod dystrophy and a frameshift mutation in the PROM1 gene. Mol Vis 15 : 1709–1716.

41. ZhangQ, ZulfiqarF, XiaoX, RiazuddinSA, AhmadZ, et al. (2007) Severe retinitis pigmentosa mapped to 4p15 and associated with a novel mutation in the PROM1 gene. Hum Genet 122 : 293–299.

42. BeryozkinA, ZelingerL, Bandah-RozenfeldD, ShevachE, HarelA, et al. (2014) Identification of mutations causing inherited retinal degenerations in the israeli and palestinian populations using homozygosity mapping. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55 : 1149–1160.

43. PermanyerJ, NavarroR, FriedmanJ, PomaresE, Castro-NavarroJ, et al. (2010) Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa with early macular affectation caused by premature truncation in PROM1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51 : 2656–2663.

44. XuD, WangY, WilleckeR, ChenZ, DingT, et al. (2006) The effector caspases drICE and dcp-1 have partially overlapping functions in the apoptotic pathway in Drosophila. Cell death and differentiation 13 : 1697–1706.

45. OkajimaT, XuA, IrvineKD (2003) Modulation of notch-ligand binding by protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 and fringe. J Biol Chem 278 : 42340–42345.

46. XuA, HainesN, DlugoszM, RanaNA, TakeuchiH, et al. (2007) In vitro reconstitution of the modulation of Drosophila Notch-ligand binding by Fringe. J Biol Chem 282 : 35153–35162.

47. Nita-LazarA, HaltiwangerRS (2006) Methods for analysis of O-linked modifications on epidermal growth factor-like and thrombospondin type 1 repeats. Methods Enzymol 417 : 93–111.

48. CuliJ, MannRS (2003) Boca, an endoplasmic reticulum protein required for wingless signaling and trafficking of LDL receptor family members in Drosophila. Cell 112 : 343–354.

49. SissonJC, FieldC, VenturaR, RoyouA, SullivanW (2000) Lava lamp, a novel peripheral golgi protein, is required for Drosophila melanogaster cellularization. J Cell Biol 151 : 905–918.

50. SatohAK, O'TousaJE, OzakiK, ReadyDF (2005) Rab11 mediates post-Golgi trafficking of rhodopsin to the photosensitive apical membrane of Drosophila photoreceptors. Development 132 : 1487–1497.

51. ChinchoreY, MitraA, DolphPJ (2009) Accumulation of rhodopsin in late endosomes triggers photoreceptor cell degeneration. PLoS Genet 5: e1000377.

52. NoloR, AbbottLA, BellenHJ (2000) Senseless, a Zn finger transcription factor, is necessary and sufficient for sensory organ development in Drosophila. Cell 102 : 349–362.

53. Fabian-FineR, VerstrekenP, HiesingerPR, HorneJA, KostylevaR, et al. (2003) Endophilin promotes a late step in endocytosis at glial invaginations in Drosophila photoreceptor terminals. J Neurosci 23 : 10732–10744.

54. SiegalML, HartlDL (1996) Transgene Coplacement and high efficiency site-specific recombination with the Cre/loxP system in Drosophila. Genetics 144 : 715–726.

55. HiguchiR, KrummelB, SaikiRK (1988) A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 16 : 7351–7367.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek The COP9 Signalosome Converts Temporal Hormone Signaling to Spatial Restriction on Neural CompetenceČlánek Coordinate Regulation of Stem Cell Competition by Slit-Robo and JAK-STAT Signaling in the TestisČlánek The CSN/COP9 Signalosome Regulates Synaptonemal Complex Assembly during Meiotic Prophase I ofČlánek GPA: A Statistical Approach to Prioritizing GWAS Results by Integrating Pleiotropy and AnnotationČlánek Functional Diversity of Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Enabling a Bacterium to Ferment Plant BiomassČlánek Heat-Induced Release of Epigenetic Silencing Reveals the Concealed Role of an Imprinted Plant GeneČlánek p53- and ERK7-Dependent Ribosome Surveillance Response Regulates Insulin-Like Peptide SecretionČlánek The Complex I Subunit Selectively Rescues Mutants through a Mechanism Independent of MitophagyČlánek Rad59-Facilitated Acquisition of Y′ Elements by Short Telomeres Delays the Onset of SenescenceČlánek ARTIST: High-Resolution Genome-Wide Assessment of Fitness Using Transposon-Insertion Sequencing

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 11- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Establishing a Multidisciplinary Context for Modeling 3D Facial Shape from DNA

- RNA Processing Factors Swd2.2 and Sen1 Antagonize RNA Pol III-Dependent Transcription and the Localization of Condensin at Pol III Genes

- Inversion of the Chromosomal Region between Two Mating Type Loci Switches the Mating Type in

- A Thermolabile Aldolase A Mutant Causes Fever-Induced Recurrent Rhabdomyolysis without Hemolytic Anemia

- The Role of Regulatory Evolution in Maize Domestication

- Stress Granule-Defective Mutants Deregulate Stress Responsive Transcripts

- 24-Hour Rhythms of DNA Methylation and Their Relation with Rhythms of RNA Expression in the Human Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex

- Pseudoautosomal Region 1 Length Polymorphism in the Human Population

- Fungal Communication Requires the MAK-2 Pathway Elements STE-20 and RAS-2, the NRC-1 Adapter STE-50 and the MAP Kinase Scaffold HAM-5

- The COP9 Signalosome Converts Temporal Hormone Signaling to Spatial Restriction on Neural Competence

- The Protein -glucosyltransferase Rumi Modifies Eyes Shut to Promote Rhabdomere Separation in

- The Talin Head Domain Reinforces Integrin-Mediated Adhesion by Promoting Adhesion Complex Stability and Clustering

- Quantitative Genetics of CTCF Binding Reveal Local Sequence Effects and Different Modes of X-Chromosome Association

- Coordinate Regulation of Stem Cell Competition by Slit-Robo and JAK-STAT Signaling in the Testis

- Genetic Analysis of a Novel Tubulin Mutation That Redirects Synaptic Vesicle Targeting and Causes Neurite Degeneration in

- A Systems Genetics Approach Identifies , , and as Novel Aggressive Prostate Cancer Susceptibility Genes

- Three RNA Binding Proteins Form a Complex to Promote Differentiation of Germline Stem Cell Lineage in

- Approximation to the Distribution of Fitness Effects across Functional Categories in Human Segregating Polymorphisms

- The CSN/COP9 Signalosome Regulates Synaptonemal Complex Assembly during Meiotic Prophase I of

- SAS-1 Is a C2 Domain Protein Critical for Centriole Integrity in

- An RNA-Seq Screen of the Antenna Identifies a Transporter Necessary for Ammonia Detection

- GPA: A Statistical Approach to Prioritizing GWAS Results by Integrating Pleiotropy and Annotation

- Let's Face It—Complex Traits Are Just Not That Simple

- Glutamate Receptor Gene , Coffee, and Parkinson Disease

- The Red Queen Model of Recombination Hotspots Evolution in the Light of Archaic and Modern Human Genomes

- The Ethics of Our Inquiry: An Interview with Hank Greely

- Functional Diversity of Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Enabling a Bacterium to Ferment Plant Biomass

- Regularized Machine Learning in the Genetic Prediction of Complex Traits

- Phylogenetically Driven Sequencing of Extremely Halophilic Archaea Reveals Strategies for Static and Dynamic Osmo-response

- Lack of Replication of the -by-Coffee Interaction in Parkinson Disease

- Natural Polymorphisms in Human APOBEC3H and HIV-1 Vif Combine in Primary T Lymphocytes to Affect Viral G-to-A Mutation Levels and Infectivity

- A Germline Polymorphism of Thymine DNA Glycosylase Induces Genomic Instability and Cellular Transformation

- Heat-Induced Release of Epigenetic Silencing Reveals the Concealed Role of an Imprinted Plant Gene

- ATPase-Independent Type-III Protein Secretion in

- p53- and ERK7-Dependent Ribosome Surveillance Response Regulates Insulin-Like Peptide Secretion

- The Complex I Subunit Selectively Rescues Mutants through a Mechanism Independent of Mitophagy

- Evolution of DNA Methylation Patterns in the Brassicaceae is Driven by Differences in Genome Organization

- Regulation of mRNA Abundance by Polypyrimidine Tract-Binding Protein-Controlled Alternate 5′ Splice Site Choice

- Systematic Comparison of the Effects of Alpha-synuclein Mutations on Its Oligomerization and Aggregation

- Rad59-Facilitated Acquisition of Y′ Elements by Short Telomeres Delays the Onset of Senescence

- A Functional Portrait of Med7 and the Mediator Complex in

- Systematic Analysis of the Role of RNA-Binding Proteins in the Regulation of RNA Stability

- ARTIST: High-Resolution Genome-Wide Assessment of Fitness Using Transposon-Insertion Sequencing

- Genomic Evidence of Rapid and Stable Adaptive Oscillations over Seasonal Time Scales in Drosophila

- Genome-Wide Associations between Genetic and Epigenetic Variation Influence mRNA Expression and Insulin Secretion in Human Pancreatic Islets

- HAM-5 Functions As a MAP Kinase Scaffold during Cell Fusion in

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- An RNA-Seq Screen of the Antenna Identifies a Transporter Necessary for Ammonia Detection

- Systematic Comparison of the Effects of Alpha-synuclein Mutations on Its Oligomerization and Aggregation

- Functional Diversity of Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Enabling a Bacterium to Ferment Plant Biomass

- Regularized Machine Learning in the Genetic Prediction of Complex Traits

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání