-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Our First Experience with Primary Lip Repair in Newborns with Cleft Lip and Palate

Autoři: J. Borský 1; M. Tvrdek 1; J. Kozák 2; Michal Černý 3

; J. Zach 4

Působiště autorů: Plastic Surgery Clinic, rd Medical Faculty and Faculty Hospital Královské Vinohrady, Charles University, Prague 1; Pediatric Stomatology Clinic, 2nd Medical Faculty and Faculty Hospital Motol, Charles University Prague 2; Obstetric and Gynecology Clinic, Department of Newborns with Intensive Care Unit, Faculty Hospital Motol, Prague, and 3; Newborn Department with Intensive Care, Thomayer Faculty Hospital, Krč, Prague, Czech Republic 4

Vyšlo v časopise: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 49, 4, 2007, pp. 83-87

INTRODUCTION

Nonsyndromic orofacial clefts are among the most frequent congenital deformities. In the Czech Republic during the years 1983–1997 the incidence was one cleft in 534 born living children. Prenatal diagnostics has improved in recent years which, together with the decreased birth-rate, has led to a gradual reduction of newborns with cleft deformity to about one child in 850 born children (7, 13, 14). The deformity significantly deforms the face esthetically, complicates food intake and breathing, and without an operation it would negatively influence speech development. Treatment starts soon after birth, continuing until adulthood, and the approach is multidisciplinary involving a team of specialized experts (plastic surgeon, phoniatrist, speech therapist, clinical psychologist, orthodontist/prosthetist, and in some cases maxillary/facial surgeon) (1, 8). Cleft deformities make it more difficult for the patient to socialize. Often they are stigmatized by postsurgical scars with typical facial deformity, less understandable speech and at times even a certain degree of hypacusia (after repeated otitis media) (4).

MATERIAL AND METHOD

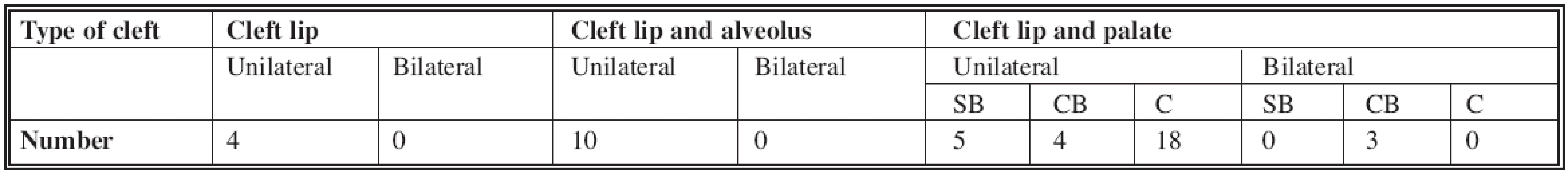

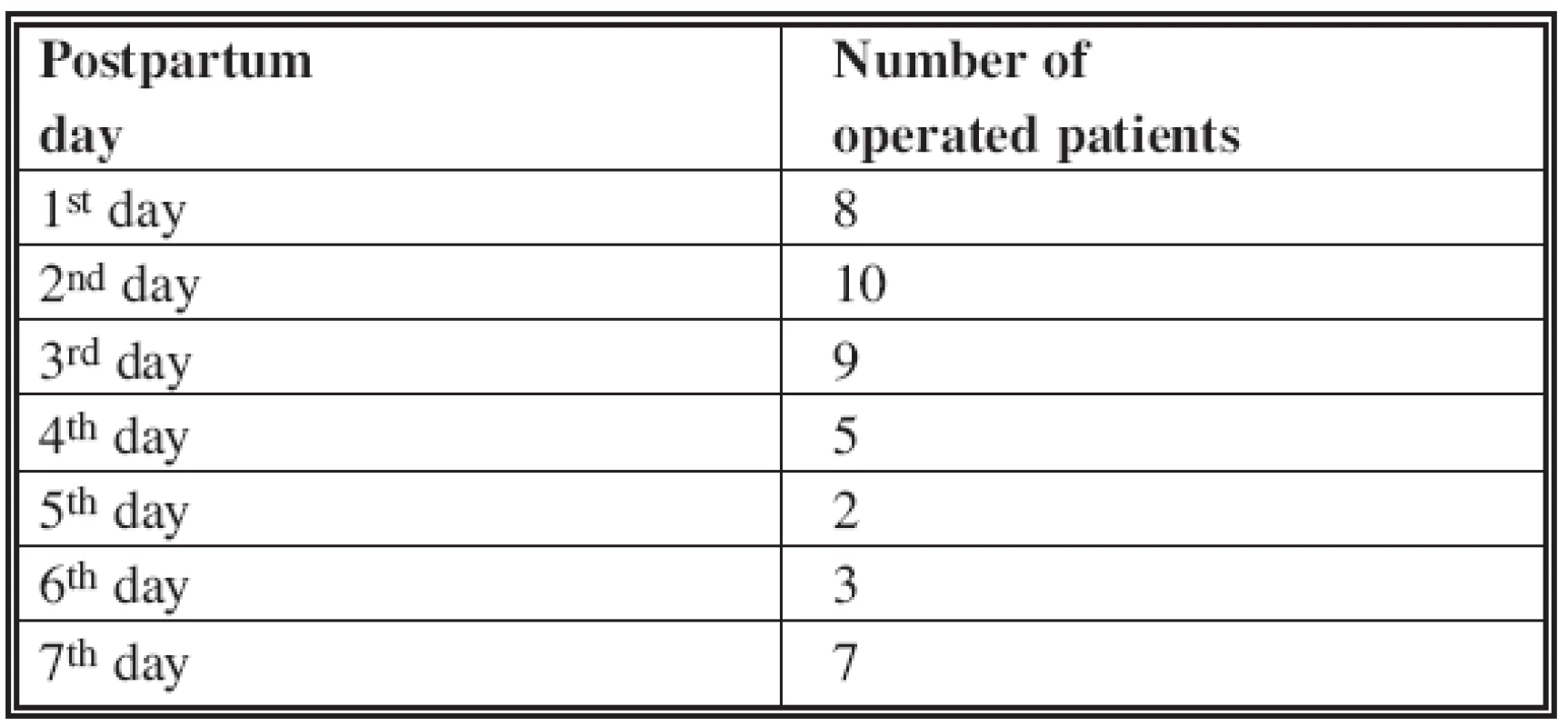

We started our early surgery in 2005 as an alternative to the common protocol, when primary lip suture is completed at the age of 3 months. The group contains 44 patients operated on at between 12 hours and 7 days after birth (Table 1, 2). The surgical method was uniform; the surgery was completed by one surgeon only. Before the surgery an imprint of the palate was taken (Fig. 1). Primary lip repair was completed by the modified method according to Tennison (Fig. 2–5) under general anesthesia (average length was 50 minutes) and after previous draft cleft edges had been cut and two mucosal flaps prepared: one for deepening the upper oral vestibulum (A), and one (B) for deepening the base and lateral side of the nasal passage and Tennison’s flap for the completion of the shortened philtrum on the cleft side. Next, the orbicularis oris muscle is isolated and tilted, and reposition of the nasal septum is completed. Finally, the rotated and dislocated alar cartilage on the cleft side is released and corrected. In the next stage, suture of the upper vestibule with deepening by the prepared flap (A) and suture of the base and the lateral side of the nasal passage with the flap (B) prepared by deepening are completed.

Tab. 1. Range of the cleft deformities of the operated patients

* SB = Soft bridge CB = combined bridge C = complete Tab. 2. Frequency of operated patients in particular days after birth

Fig. 1. Plaster cast of the cleft of the second patient

Fig. 2. Diagram of the surgery slices according to Tennison’s modified method – view of the lip

Fig. 3. Diagram of the surgery slices according to Tennison’s modified method – view of the buccal cavity

Fig. 4. Elevated mucosal flaps: A for the deepening of the vestibule, B for the deepening of the base and the side of the nasal passage

Fig. 5. Diagram of the postsurgical scar

Next, suture of the lip muscle is completed, the released and corrected nasal septum is pushed into the cut in the side of the columella, lip suture is completed, Tennison’s flap is pushed into the separate cut and lastly suture of the red part of the upper lip is completed. Suture is completed by Vicryl 6/0 and covered on the external side of the lip by sterile tape. After surgery the intubated newborn babies were transferred to a specialized newborn intensive care unit, where they remained in care until extubation, which was performed 12–24 hours after surgery. Afterwards they were offered breast or were fed by an artificial nipple. The newborn babies were discharged from the hospital around the 5th day after the surgery. After the surgery they temporarily wore silicone nostrils (Fig. 6) which retain the shape of the corrected nasal septum. Patients remain in the multidisciplinary team care of the plastic surgery department. We complete repair of the palate between the 6th and 12th month of age according to the extent of the deformity. All surgeries were uncomplicated. In the post-surgical period we recorded an allergic reaction to silicon in one case. An allergologist confirmed polyvalent allergy in this patient, to silicon among others. Children are systematically monitored. Preliminary evaluation of the achieved results is based on the following parameters: shape and lip symmetry, scar appearance, its width, speed of maturing, symmetry of the position and distance of alae nasi, nasal tip and nostrils. Due to the short interval from the surgery we cannot yet objectify the results, and because of the short time span we do not evaluate potential impact on maxillary growth. Evaluation of the preliminary results shows that it will likely be necessary to complete small cosmetic corrections in later years, such as correction of an excess red part of the lip, correction of small mucous plica of the nasal passage or approximation of the wing of the nostril in about 25% of the operated patients.

Fig. 6. Nostrils made by the Erilens Company

RESULTS

We operated on 44 patients less than 1 week old: the youngest was 12 hours, the oldest 7 days old (see Table 1, 2); 61% of patients underwent the surgery before the third day of their life. Preoperatively there were no complications. In postoperative courses we noted one allergic reaction to silicone, which was later confirmed by the allergologist as a polyvalent allergy. This patient healed i. p.p. Postoperatively, we have found very good results in patients (nose and lip). Scars mature faster than in children operated according to the common protocol at the age of 3 months, and they are barely visible after 8 months. As an illustration we present two patients: the first with a cleft lip and indentation into maxilla on the right side (Fig. 7–10), and the second with a complete right-sided cleft (Fig. 11–15).

Fig. 7. First patient with incomplete lip cleft and indentation into the maxilla first day after birth, when he underwent surgery

Fig. 8. First patient with incomplete lip cleft and indentation into the maxilla first day after birth, when he underwent surgery

Fig. 9. First patient 8 months after primary lip suture

Fig. 10. First patient 8 months after primary lip suture

Fig. 11. Second patient with complete right-sided cleft of the lip and palate second day after birth when she underwent surgery

Fig. 12. Second patient with complete right-sided cleft of the lip and palate second day after birth when she underwent surgery

Fig. 13. Second patient 8 months after primary lip suture

Fig. 14. Second patient 8 months after primary lip suture

Fig. 15. 3D model of the upper jaw in a newborn with wide unilateral complete cleft lip and palate prepared for 3D measurement

DISCUSSION

A specialist study (19) involves 260 workplaces from around the world where about 6400 primary repairs of the lip are performed annually. The study shows the following information: Primary repair of the lip is performed before the child is one month old at 33.3% of workplaces; 65.9% of the workplaces complete the surgery when the child is 3–6 months old, and only 0.7% of the workplaces complete primary repair of the lip at the age of 6 months or later. The given data show that about a third of workplaces around the world prefer early surgery. A further study (15) refers to about 178 cleft centers that have 171 various protocols of treatment of unilateral clefts.

Cannon (3) recommends the first 24 hours after birth as an optimal time for primary repair of the lip. Lewin (9) considers the optimal time for primary repair of the lip to be the time between 6–12 weeks after birth on the basis that there is less risk concerning anesthesia, the lip is bigger and allows for more accurate work for the surgeon, and parents accept postponing of the surgery well.

Wilhelmsen and Musgrave (20) recommend what is known as the rule of 10: The child should weigh 10 pounds, the level of hemoglobin should be 10 or more, and leucocytes should be less than 10,000. These authors warn that if this rule is not respected the level of postsurgical complications significantly increases.

Weatherley-White et al. (18) did not find any difference in morbidity in children operated on during the first three weeks after birth or in children operated on later. Stark (16) recommends primary repair during the first 14 days after birth as safe. From the surgical point of view the lip grows only 2 mm in the vertical direction during the first 3 months of life.

Mcheik et al. (11) mention 10 years of experience with early surgery (under 1 month of age) in 123 children and report very good results.

Bromley (2) did not find increased morbidity after surgeries in children under the age of one week.

Yuzuriha et al. (21) present a comparative study of post-operative results in 52 patients after 15 years of age of which 42 underwent primary lip repair under the age of 1 month, while for the remaining 11 patients primary repair was completed around the age of 3 months. The need for secondary lip correction was lower in the first group of patients (who underwent operations during newborn age). The impact of primary lip suture on maxillary growth was not confirmed. Newborn tissues are very delicate and fragile, and the surgical result is influenced by the surgical technique as well as the skills and proficiency of the whole therapeutic team. Esthetic results are very good, and the child’s family protected from a great psychological burden at this stage.

Mcheik and Levard (12) present a study about the psychological impact of the diagnosis in mothers of children with a cleft diagnosed prenatally and postnatally. A group of 24 mothers of children with clefts was psychologically analyzed in detail. The results confirmed the presence of stress, misunderstanding about the situation, anxiety caused by the cleft and great satisfaction and joy after early lip surgery.

Goodacre et al. (5) present a comparative study of surgical results in children with clefts operated on during newborn age and at the age of 3 months, concluding that primary repair in newborn age does not bring any significant advantages.

In our group of patients we have not registered any complications caused by the surgery or anesthesia. In the post-operative period only one complication arose, though this was not related to the surgery, which was an allergic reaction to Topigel-silicon (this child was later diagnosed with a polyvalent allergy, also to silicon). The timing of the surgeries was between 12 hours after birth to 7 days after birth. The weight of children was between 1200g and 4330g. Children were carefully evaluated by a neonatologist, and other associated deformities which would have taken priority over cleft surgery were excluded. The surgical procedure was uniform; the same surgeon performed all the surgeries. The children were hospitalized for 5 days on average. The nasal passages were temporarily supported by nostrils. The parents cooperated without any problems, and they greatly appreciated results of the whole multidisciplinary team work.

CONCLUSION

Our preliminary results after early primary lip repair are very encouraging, and we consider it to be the best method. Evaluation of the preliminary results show that it will probably be necessary to complete small cosmetic corrections at a later age in approximately 25% of operated patients; that is one percent less than in patients operated according to the classic procedure. Due to the short time span we cannot evaluate possible impact on maxillary growth. We will continue in this type of surgery and evaluate its other aspects, along with its impact on the maxillary and nasal development. To significantly improve the appearance of patients with cleft, improve quality of scars, food intake, speech, hearing and to decrease the psychological impact of this deformity on the whole family are the primary objectives in this era of plastic surgery.

Address for correspondence:

J. Borský, M.D.

Šrobárova 50

100 34 Prague 10

Czech Republic

E-mail: jiri.borsky@tiscali.cz

Zdroje

1. Bardach J., Morris HL. (Eds). Multidisciplinary Management of Cleft Lip and Palate. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1990, p. 586–591.

2. Bromley GS., Rothmans KO., Goulian D. Cleft lip: Morbidity and mortality in early repair. Ann. Plast. Surg., 10, 1983, p. 214–217.

3. Cannon B. Current concepts: Unilateral cleft lip. N. Eng. J. Med., 277, 1967, p. 583–585.

4. Desai SN. Neonatal Surgery of the Cleft Lip and Palate, Stoke Mandewille Hospital Buckinghamshire UK, World Scientific Publishing Co Pte, Ltd., 1997.

5. Goodacre TE., Hentges F., Moss TL., Short V., Murray L. Does repairing a cleft lip neonatally have any effect on the longer-term attractiveness of repair? Cleft Palate Craniofac. J., 41, 2004, p. 603–608.

6. Goodrich JT., Hall CD. Craniofacial Anomalies Growth and Development from a Surgical Perspective. 1st ed. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, 1995, p. 149–174.

7. Klásková O. Incidence of cleft lip and palate in Bohemia (in Czech). Rozhl. Chir., 53, 1974, p. 147–150.

8. Kuderová J., Borský J., Černý M., Müllerová Ž., Vohradník M., Hrivnáková J. Care of patients with facial clefts at the department of plastic surgery in Prague. Acta Chir. Plast., 38, 1996, p. 99–103.

9. Lewin ML. Management of cleft lip and palate in the United States and Canada. Plast. Reconstr. Surg., 33, 1964, p. 383.

10. McCarthy JG. Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders, 1990, vol. 4, p. 2632–2633.

11. Mcheik JN., Levard G. Neonatal lip repair, psychological impact on mothers. Archives dé Pédiatrie, 13, 2006, p. 346–351.

12. Mcheik LN., Sfalli P., Bondonny JM., Levard G. Early repair for infants with cleft lip and nose. Internat. J. Ped. Otorhinolaryngol., 70, 2006, p. 1785–1790.

13. Peterka M., Peterková R., Likovský Z., Tvrdek M., Fára M. Incidence of orofacial clefts in Bohemia (Czech Republic) in 1964–1992. Acta Chir. Plast., 37, 1995, p. 122–126.

14. Peterka M., Peterková R., Tvrdek M., Kuderová J., Likovský Z. Significant differences in the incidence of orofacial clefts in fifty-two Czech districts between 1983–1997. Acta Chir. Plast., 42, 2000, p. 124–129.

15. Semb G., Shaw WC. Facial growth after different methods of surgical interventions in patients with cleft lip and palate. Acta Odont. Scand., 56, 1998, p. 352–355.

16. Stark BP. Cleft Palate. New York: Hoeber, 1968.

17. Tvrdek M., Hrivnáková J., Kuderová J., Šmahel Z., Borský J. Influence of primary septal cartilage reposition on development of the nose in UCLP. Acta Chir. Plast., 39, 1997, p. 113–116.

18. Weatherley-White RCA., Kuehn DP., Miret P., Gilman JJ., Weatherley-White CC. Early repair and breast-feeding for infants with cleft lip. Plast. Reconstr. Surg., 79, 1987, p. 879–885.

19. Weinfeld AB., Hollier LH., Spira M., Stal S. International trends in treatment of cleft lip and palate. Clin. Plast. Surg., 32, 2005, p. 19–23.

20. Wilhelmsen HR., Musgrave RH. Complication of Cleft Lip Surgery. Cleft Palate. New York: Hoeber, 1968.

21. Yuzuriha S., Matsuo K., Kondoh S., Narimatsu I., Yano S. Primary lip repair in newborn babies with unilateral cleft lip, long term follow up. Jpn. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg., 49, 2006, p. 483–491.

Štítky

Chirurgie plastická Ortopedie Popáleninová medicína Traumatologie

Článek vyšel v časopiseActa chirurgiae plasticae

Nejčtenější tento týden

2007 Číslo 4- Metamizol jako analgetikum první volby: kdy, pro koho, jak a proč?

- Metamizol v léčbě různých bolestivých stavů – kazuistiky

- Neodolpasse je bezpečný přípravek v krátkodobé léčbě bolesti

- Léčba akutní pooperační bolesti z pohledu ortopeda

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- TREPHINATIONS – OLD SURGICAL INTERVENTION

- ČESKÉ SOUHRNY

- CONTENTS

- INDEX

- Our First Experience with Primary Lip Repair in Newborns with Cleft Lip and Palate

- DENTURE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE EDENTULOUS UPPER JAW IN CLEFT PALATE USING IMPLANTS – CLINICAL REPORT

- SATISFACTION AND COMPLICATIONS IN POST-BARIATRIC SURGERY ABDOMINOPLASTY PATIENTS

- NECROTIZING FASCIITIS AFTER LIPOSUCTION

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Our First Experience with Primary Lip Repair in Newborns with Cleft Lip and Palate

- TREPHINATIONS – OLD SURGICAL INTERVENTION

- NECROTIZING FASCIITIS AFTER LIPOSUCTION

- SATISFACTION AND COMPLICATIONS IN POST-BARIATRIC SURGERY ABDOMINOPLASTY PATIENTS

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání