-

Medical journals

- Career

Transcranial magnetic stimulation in borderline personality disorder – case series

Authors: T. Sverak 1; P. Linhartová 1; M. Kuhn 1; A. Latalova 1; B. Bednarova 1; L. Ustohal 1,2; T. Kasparek 1,3

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Psychiatry, Masaryk, University and University Hospital, Brno, Czech Republic 1; Applied Neurosciences Research, Group, Central European Institute of, Technology, Masaryk University (CEITEC, MU), Brno, Czech Republic 2; Behavioral and Social Neuroscience, Group, Central European Institute of, Technology, Masaryk University (CEITEC, MU), Brno, Czech Republic 3

Published in: Cesk Slov Neurol N 2019; 82(1): 48-52

Category: Original Paper

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn201948Overview

Aim:

We present the results of a case series study of individually navigated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in four patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD).

Patients and methods:

Four patients with BPD performed a Go/ NoGo task during functional MRI (fMRI) designed for observing behavioural inhibition neural correlates. The site within the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex with the largest difference in BOLD signal between the NoGo and Go conditions was assigned as a target for rTMS in each patient. Four patients underwent 15 sessions of individually navigated 10-Hz rTMS treatment at 110% of their individual resting motor threshold for 3 weeks (one session per working day). One session contained 1,500 pulses delivered in 15 trains by 10 s, leading to a total of 22,500 pulses during the treatment.

Results:

The treatment was very well tolerated without any serious side effects. After the treatment, the patients reported that they felt better self-control of their emotions, especially anger; that their urges for self-harm and suicidal thoughts decreased or disappeared; and that their derealisation/ depersonalisation episodes disappeared. Patients also showed less depression symptoms after the treatment.

Conclusion:

rTMS with neuronavigation individualised by a fMRI Go/ NoGo task is a promising tool for reducing impulsive behaviour and enhancing emotion regulation in BPD patients. Double-blind placebo-controlled studies in larger samples are necessary to draw further conclusions about rTMS effectiveness in BPD.

Key words

repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation – rTMS – borderline personality disorder – impulsivity – emotion regulation – Go/NoGo task – neuronavigation

边缘性人格障碍的经颅磁刺激 - 病例系列

目的:

我们报告了4例边缘性人格障碍(BPD)患者的个体化导航重复经颅磁刺激(rTMS)病例研究结果。

患者和方法:

4例BPD患者在功能磁共振成像(fMRI)中进行了Go/ NoGo任务,以观察行为抑制神经相关。将NoGo和Go条件下BOLD信号差异最大的右侧背外侧前额叶皮质区域作为每个患者的rTMS靶点。4名患者接受了15次10赫兹rTMS治疗,每次治疗时间为3周(每天1次),每次治疗时间为其静息运动阈值的110%。其中一个疗程包括15列火车在10秒内发出的1500次脉冲,治疗期间总共产生了22,500次脉冲。

结果:

这种疗法耐受性很好,没有任何严重的副作用。治疗后,患者报告说,他们感觉更好地控制自己的情绪,尤其是愤怒;他们对自我伤害和自杀想法的冲动减少或消失了;他们的去人格化/去人格化症状消失了。治疗后患者的抑郁症状也减少了。

结论:

功能磁共振Go/ NoGo任务个性化神经导航rTMS是一种很有前途的工具,可以减少BPD患者的冲动行为,增强情绪调节。为了进一步研究rTMS对BPD的疗效,需要对更大样本进行双盲安慰剂对照研究。

关键字

重复经颅磁刺激 - rTMS -边缘性人格障碍-冲动-情绪调节 - Go/NoGo任务-神经导航

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a devastating pervasive mental illness with an estimated prevalence between 1 and 2% in the general population, up to 10% in psychiatric outpatients, and up to 20% in psychiatric inpatients [1]. The core elements in BPD include marked impulsivity and impaired emotional processing [2]. Patients have increased emotional reactivity with longer time needed for their emotions to return to baseline [3]. At the same time, BPD patients have decreased abilities to regulate emotions [4]. Impulsivity in BPD occurs most often under the influence of emotions and manifests in various forms of risky (self-) destructive behaviour (e. g., drug abuse, risky sexual behaviour, binge eating, aggression, and self-harm, including frequent suicide attempts [1,5,6]). More than 10% of patients with BPD commit suicide, which is about 50 times more than in the general population [7]. Thus, targeting emotional regulation and behavioural inhibition appears crucial for preventing dangerous impulsive behaviour and its consequences in BPD patients [3,8].

On the neural level, emotion regulation and behavioural inhibition are associated with functional impairment of the prefrontal-limbic network [4,9]. In the limbic system, the amygdala has been shown to be hyperactive when processing emotional stimuli; this has been found to be associated with impulsive reactions [3,10 – 12]. Several authors associate impulsive behaviour with altered activity in other frontal regions (primarily the orbitofrontal cortex, ventromedial cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) [12 – 14]). The DLPFC plays an important role in cognitive emotion top-down regulation and in decision making [15,16]. In light of the crucial role of impaired prefrontal areas in BPD patients, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a promising treatment tool because these regions are easily accessed by rTMS coils.

We present our pilot results with rTMS treatment of BPD at the Department of Psychiatry of the University Hospital Brno. To our knowledge, rTMS treatment has not been used in BPD patients in the Czech Republic; five articles [17 – 21] about rTMS and BPD are available in the literature. We introduce individual neuronavigation of rTMS to the right DLPFC (rDLPFC) using individual results from a Go/ NoGo (GNG) task in functional MRI (fMRI) with the aim of finding the most individually suitable target for treating self-control difficulties for the fist time.

Patients and methods

Research sample

Four patients who met the criteria for BPD according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [22], were recruited in our case series study (3 women; average age 22 ± 3.9 years; average years of education 11.75 ± 1.89). Three patients were outpatients during the treatment and one patient was hospitalised at the Department of Psychiatry of the University Hospital Brno during the treatment. All patients had to be on stable medication from 6 weeks before the stimulation until the end of the stimulation. The exclusion criteria were addiction, acute psychotic state, severe depression, and contraindications preventing MRI or rTMS.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Prior to treatment, the patients underwent fMRI with 3T machines Siemens Magnetom Prisma (Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) at the Central European Institute of Technology (CEITEC) in Brno, Czech Republic. During fMRI, the patients performed a GNG task (TR = 2.280 ms; TE = 35 ms; res. 3 × 3 × 3 mm). The stimulation coil was targeted at the site with the individually highest activation in the NoGo > Go contrast, representing a crucial point for patients’ behavioural inhibition.

Go/ NoGo task

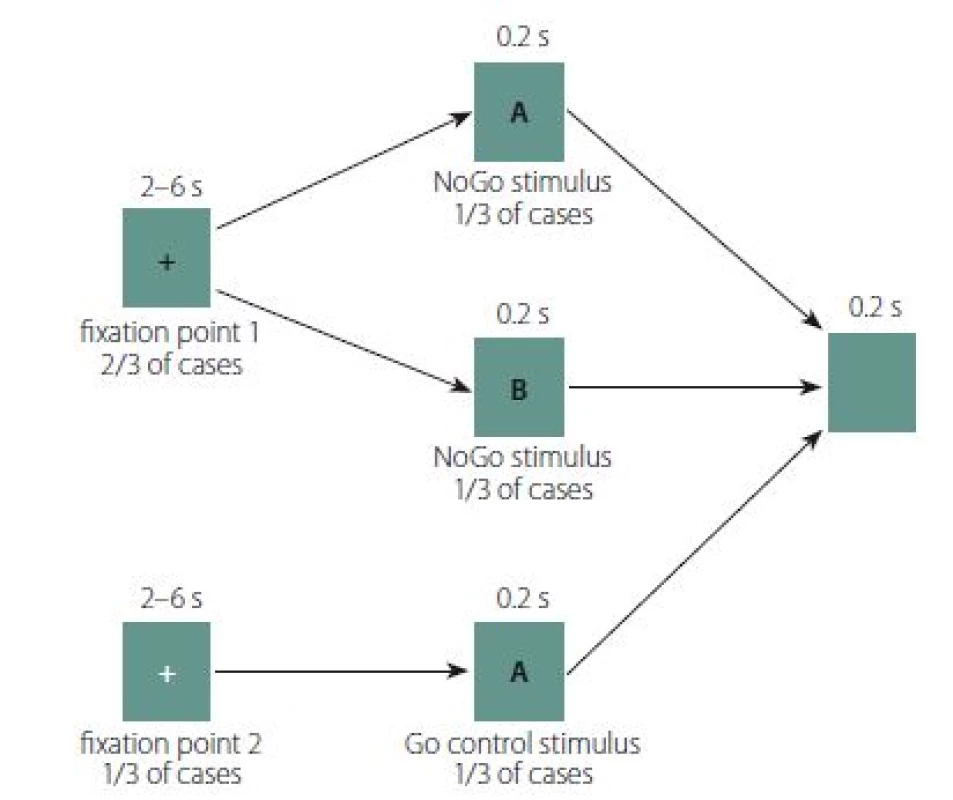

The GNG task design was adapted from Albares et al. [23] (Fig. 1). Each trial in the GNG task consisted of a fixation point lasting between 2 and 6 s, followed by either the Go or NoGo stimulus for 0.2 s, followed by a post-trial black screen for 2 s. White letters A and B on a black background were used as the Go and NoGo stimuli. In 2/ 3 of cases, the fixation point was a red cross; 1/ 3 of the crosses were green. The patients were instructed that either a Go or NoGo stimulus would appear after the red cross, while the green cross would always be followed by a Go stimulus. Patients were further instructed to press a button as quickly as possible whenever the Go stimulus appeared, but not to press the button when the NoGo stimulus appeared (i.e., to perform behavioural inhibition). The task contained 4 blocks of 54 trials each.

Determining the stimulation point

Data analysis was performed in SPM12 (The FIL Methods Group, London, United Kingdom). In our previous analysis, we found that the behavioural inhibition network was more activated during the NoGo condition after the red cross (NoGoRed) than during the Go condition after the red cross (GoRed). Based on these results, the site with the maximum BOLD signal within the rDLPFC in NoGoRed > GoRed contrast was found and used as the rTMS target. The individual rDLPFC mask was derived from the Destrieux Atlas [24] from FreeSurfer software (The General Hospital Corporation, Boston, MA, USA) [25], combining areas from the sulcus frontalis inferior and sulcus frontalis superior to gyrus frontalis medius. The individual rDLPFC mask was obtained by processing anatomical images of each patient using the FreeSurfer 5.3.0 software [25]. The stimulation coil was subsequently targeted to the highest point of NoGoRed > GoRed contrast in the patient’s rDLPFC by Brainsight software TMS neuronavigation, ver. 2.2 (Rogue Research Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada).

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation protocol

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation was performed by DuoMag XT (Rogue Resolutions Ltd, Cardiff, United Kingdom) with a 70BF cool coil. Patients underwent 15 stimulation sessions at 110% of their individual resting motor threshold (MT) over a period of 3 weeks with one session each working day. Patients received 1,500 pulses during one session (total 22,500 pulses during the whole procedure) with 10 Hz frequency. Train lasted 10 s with inter-train interval of 30 s. The MT was measured before the first stimulation session; it was defined as the lowest possible intensity inducing at least five motor responses from 10 pulses in the primary motor cortex above 50 μV measured from the abductor pollicis brevis muscle (measured by EMG, a component of the DuoMag XT stimulator).

Rating scales and semi-structured interview

Patients were assessed using the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Clinical Global Impressions (CGI), and semi-structured interviews. This battery was presented to patients before and after the rTMS treatment. MADRS [26] assesses the presence and severity of depressive symptoms. High-frequency stimulation of rDLPFC could cause depression [27] or have a positive or negative effect on mood [28,29]. This scale was included to monitor any worsening of patient mood. CGI scales are measures of symptom severity, treatment response, and treatment efficacy in patients with mental disorders [30]. The effect of rTMS on impulsive symptoms and emotion regulation was captured by semi-structured interviews focused on the patient’s individual symptoms.

These four patients were part of a larger open study for evaluating the neural effects of rTMS in BPD patients; they were assessed by an unblinded rater.

Results

The average Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital coordinate of the stimulated point in the rDLPFC area was: x = 26.49 ± 2.92; y = 60.89 ± 13.65; z = 57.01 ± 9.23. Treatment with rTMS was very well tolerated without any serious side effects. Two patients reported headaches at the stimulation coil site lasting about 2 h that spontaneously resolved. The following results constitute qualitative case reports based on semi-structured interviews completed with MADRS and CGI before and after the stimulation protocol.

Case study 1

The first patient (20-year-old woman) was medicated with 50 mg sertraline daily. She was treated as an outpatient and had never been hospitalised. She was self-harming by scratching and cutting herself at a frequency of approximately once in 30 – 40 days; had long-term suicidal thoughts, but had never attempted suicide; felt social withdrawal and increased fear of people in social situations; and experienced frequent bursts of anger towards others.

After the rTMS treatment, the patient reported that her ability to recognise her emotions increased, and she was thus better able to regulate emotions. She reported that especially when she was upset in social situations or when she had the urge to hurt herself, she was able to stop and think about what she wanted to do about her urgency or emotional state. She did not harm herself during the treatment and reported fewer emotional outbursts. Moreover, she reported markedly improved attention. Her mood, as rated by MADRS, improved from 19 to 14 points and the CGI was improved from markedly ill (5) to mildly ill (3). Her illness was much improved (2) after the treatment.

Case study 2

The second patient (23-year-old man) was medicated with 10 mg of escitalopram and had been treated since the age of 20. He did not self-harm before the treatment; he had been having suicidal thoughts once a week since the age of 21 and he had attempted suicide four times. He was easily irritated with low frustration toleration. He had problems controlling anger and reported difficulties in concentration.

After the rTMS, the patient reported that he experienced anger at a lower intensity and happiness as more intense, and his irritability decreased, leading to calmer feelings. He also reported that he feels like he has more time to think before speaking impulsively and his attention markedly increased. His MADRS score decreased from 2 to 0 points; CGI improved from moderately ill (4) to mildly ill (3). His illness was minimally improved (3) after the treatment.

Case study 3

The third patient (18-year-old woman) had no medication, was hospitalised twice, and had been treated since the age of 16. She had suicidal thoughts lasting for two years with no suicide attempt, was self-harming by cutting, hitting with a meat gavel, or scratching herself to the point of bleeding every day for two years. In connection with self-harming, she described that she had pseudo-hallucinatory experiences in the form of a man’s voice encouraging her to harm herself and insulting her. She reported that she often said things she immediately regretted; she had outbursts of anger, screaming at people and threatening them; she had frequent episodes of derealisation; and she had abused alcohol daily for 2 years; however, she was abstinent at the beginning of the rTMS treatment.

After the rTMS, the patient improved in her emotion regulation in stressful situations and in anger management. She experienced emotions as intense, but she could better recognise and control them. She did not experience any derealisation episodes and the voice in her head vanished and she also has managed to avoid harming herself, reporting decreased anxiety, improved attention, and improved sleep during the treatment. According to the clinical rating, her mood improved significantly (MADRS dropped from 20 to 3 points) and her CGI decreased from severely ill (6) to mildly ill (3). She was much improved (2) after the treatment.

Case study 4

The fourth patient (27-year-old woman) had been medicated with 11 different psychotropics (citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, trazodone, quetiapine, chlorprothixene, topiramate, lithium, buspirone, promethazine, haloperidol) during her treatment from 1998 to 2017 and underwent 6 psychiatric hospitalisations. She was medicated with lithium, quetiapine, and chlorprothixene at the time of stimulation. She had suicidal thoughts every day and had harmed herself by cutting with a razor blade and bleeding from her veins every day since she was 23, and had attempted suicide 3 times by cutting her veins, had demonstrated risky sexual behaviour (approximately 80 sexual partners over 12 years, although she was married for 5 of those years). She often felt uncontrolled anger toward people around her.

From the beginning of the second treatment week, she reported spontaneous inexplicable crying, after which she felt significant relief. After the treatment, she reported reduced urges for self-harm, better anger management, especially in interpersonal situations, improved attention, decreased anxiety, and improved mood (MADRS from 16 to 11). Her CGI improved from markedly ill (5) to moderately ill (4) and she was minimally improved (3) after the treatment.

Discussion

We report the first study in the Czech Republic using individual fMRI-based navigating rTMS and examining the therapeutical potential of rTMS in BPD patients. rTMS appeared to be well tolerated without serious side effects and led to reduced BPD symptoms in individual patients. After treatment, the patients described increased emotional awareness, which subsequently helped them to regulate emotions more efficiently. Tendency to self-harm, vague suicidal thoughts, derealisation, and increased affective irritation were not experienced by patients approximately from mid-treatment to the end of the treatment. Patients described improved moods and marked improvement in their attention among other effects of rTMS treatment.

Our results are in line with the existing literature, 5 articles focused on treating BPD symptoms with rTMS [17,19 – 21,31]. Individual studies reported similar outcomes in BPD patients in terms of better self-control and emotional regulation, improved mood, and decreased anxiety. Despite the similar pattern of rTMS effects in BPD, studies differ substantially in stimulation parameters, including stimulation brain targets.

Based on previous results, high frequency rTMS should lead to increased metabolism in the stimulated area [32,33]. This could lead to increased prefrontal-limbic connectivity, which represents top-down cognitive emotion regulation, but there has not been a study proving this mechanism. Such effects should lead to improved affective stability, emotion regulation, and impulsivity symptoms as was observed in this pilot study and previous studies. There has not yet been a study about the mechanism of the neural effect of rTMS, optimal stimulation parameters, and the best area for the stimulation in BPD patients.

The limits of our study include the small pilot sample of BPD patients and the prevalence of subjective reports for effects description. Future studies should test rTMS treatment in larger patient samples using protocols for results evaluation, including questionnaires and behavioural tests specifically for BPD patients (like Minnesota Borderline Personality Disorder Scale [MBPD] [34] and the Borderline Symptom list 23 [BSL-23] [35]). We focused primarily on the tolerability of stimulation and clinical effects perceived by patients in our study, but it would be appropriate to quantify and objectivise the effect with at least the above-mentioned scales. Neural effects of rTMS treatment in BPD should also be assessed.

We only observed the patients during the time of treatment. Future studies should evaluate the long-term effects of rTMS in BPD, because the persistence of the effect over time has not yet been examined. The literature about rTMS in depression indicates that the positive effect could persist for 4 to 5 months [36,37]. The maintenance treatment after this time should be further examined. One possibility would be to administer rTMS twice weekly for 1 month, once weekly for 2 months, and twice monthly for 9 months (see in [38]). Because the effects of rTMS in BPD were demonstrated mainly in emotional dimensions, it could be more appropriate to navigate rTMS using an emotional GNG task in future. The study lacked a control group. There are not many double-blind placebo-controlled trials of rTMS in BPD. However, rTMS protocol could possibly induce placebo effects. For the duration of the treatment, the patients visited our department daily and were frequently asked about their state. Double-blind placebo-controlled studies are needed to exclude the influence of placebo effects of rTMS protocols in BPD patients.

Conclusion

The current literature suggests that rTMS is a well-tolerated treatment without any serious side effects in BPD patients and a potentially useful tool for reducing BPD symptoms, including impulsivity and emotion regulation impairment. However, double-blind placebo-controlled studies in larger samples of patients with BPD are needed to further evaluate this method of BPD treatment.

The contribution was supported by the grant of AZV MZ ČR 15-30062A and the project-specific university research of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic MUNI/ A/ 0976/ 2017 and by institutional support MH CZ Development of Research Organization FNBr, 65269705.

We acknowledge the core facility MAFIL of CEITEC supported by the Czech-BioImaging large RI project (LM2015062 funded by MEYS CR) for their support with obtaining scientific data presented in this paper.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Mgr. Tomas Sverak

Department of Psychiatry

Masaryk University

University Hospital Brno

Jihlavska 20

625 00 Brno

Czech Republic

e-mail: tomas.sverak@mail.muni.cz

Accepted for review: 15. 7. 2018

Accepted for print: 10. 12. 2018

Sources

1. Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C et al. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 2004; 364(9432): 453– 461. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(04)16770-6.

2. Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE. Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50(12): 971– 974. doi: 10.1001/ archpsyc.1993.01820240055007.

3. Donegan NH, Sanislow CA, Blumberg HP et al. Amygdala hyperreactivity in borderline personality disorder: implications for emotional dysregulation. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54(11): 1284– 1293. doi: 10.1016/ S0006-3223(03)00636-X.

4. Schulze L, Schmahl C, Niedtfeld I. Neural correlates of disturbed emotion processing in borderline personality disorder: a multimodal meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry 2016; 79(2): 97– 106. doi: 10.1016/ j.biopsych.2015.03.027.

5. American Psychiatric Association. The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. DSM 5. 5th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing 2013.

6. Cyders M, Combs J, Fried RE et al. Emotion-based impulsivity and its importance for impulsive behavioral outcomes. In: Lassiter GH (ed). Impulsivity: causes, control and disorders. New York: Nova Science Publishers 2009 : 105– 126.

7. Oldham JM, Gabbard GO, Goin MK, American Psy-chiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158(Suppl 10): 1–52.

8. Ansell EB, Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH et al. Psychosocial impairment and treatment utilization by patients with borderline personality disorder, other personality disorders, mood and anxiety disorders, and a healthy comparison group. Compr Psychiatry 2007; 48(4): 329– 336. doi: 10.1016/ j.comppsych.2007.02.001.

9. Wager TD, Davidson ML, Hughes BL et al. Prefrontal-subcortical pathways mediating successful emotion regulation. Neuron 2008; 59(6): 1037– 1050. doi: 10.1016/ j.neuron.2008.09.006.

10. Mitchell AE, Dickens GL, Picchioni MM. Facial emotion processing in borderline personality disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev 2014; 24(2): 166– 184. doi: 10.1007/ s11065-014-9254-9.

11. De La Fuente JM, Goldman S, Stanus E et al. Brain glucose metabolism in borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1997; 31(5): 531– 541. doi: 10.1016/ S0022-3956(97)00001-0.

12. Soloff PH, Pruitt P, Sharma M et al. Structural brain abnormalities and suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2012; 46(4): 516– 525. doi: 10.1016/ j.jpsychires.2012.01.003.

13. Matsuo K, Nicoletti M, Nemoto K et al. A voxel-based morphometry study of frontal gray matter correlates of impulsivity. Hum Brain Mapp 2009; 30(4): 1188– 1195. doi: 10.1002/ hbm.20588.

14. Soloff PH, Meltzer CC, Becker C et al. Impulsivity and prefrontal hypometabolism in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2003; 123(3): 153– 163. doi: 10.1016/ S0925-4927(03)00064-7.

15. Kohn N, Eickhoff SB, Scheller M et al. Neural network of cognitive emotion regulation – an ALE meta-analysis and MACM analysis. Neuroimage 2014; 87 : 345– 355. doi: 10.1016/ j.neuroimage.2013.11.001.

16. Krain AL, Wilson AM, Arbuckle R et al. Distinct neural mechanisms of risk and ambiguity: a meta-analysis of decision-making. Neuroimage 2006; 32(1): 477– 484. doi: 10.1016/ j.neuroimage.2006.02.047.

17. Arbabi M, Hafizi S, Ansari S et al. High frequency TMS for the management of Borderline Personality Disorder: a case report. Asian J Psychiatr 2013; 6(6): 614– 617. doi: 10.1016/ j.ajp.2013.05.006.

18. Cailhol L, Roussignol B, Klein R et al. Borderline personality disorder and rTMS: a pilot trial. Psychiatry Res 2014; 216(1): 155– 157. doi: 10.1016/ j.psychres.2014.01.030.

19. De Vidovich GZ, Muffatti R, Monaco J et al. Repetitive TMS on left cerebellum affects impulsivity in borderline personality disorder: a pilot study. Front Hum Neurosci 2016; 10 : 582. doi: 10.3389/ fnhum.2016.00582.

20. Feffer K, Peters SK, Bhui K et al. Successful dorsomedial prefrontal rTMS for major depression in borderline personality disorder: Three cases. Brain Stimul 2017; 10(3): 716– 717. doi: 10.1016/ j.brs.2017.01.583.

21. Reyes-López J, Ricardo-Garcell J, Armas-Castañeda G et al. Clinical improvement in patients with borderline personality disorder after treatment with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: preliminary results. Braz J Psychiatry 2018; 40(1): 97– 104. doi: 10.1590/ 1516-4446-2016-2112.

22. Ustohal L, Přikrylová Kučerová H, Přikryl R et al. Repetitivní transkraniální magnetická stimulace v léčbě depresivní poruchy – randomizovaná, jednoduše slepá, antidepresivy kontrolovaná studie. Cesk Slov Neurol N 2014; 77/ 110(5): 602– 607.

23. Albares M, Lio G, Criaud M et al. The dorsal medial frontal cortex mediates automatic motor inhibition in uncertain contexts: evidence from combined fMRI and EEG studies. Hum Brain Mapp 2014; 35(11): 5517– 5531. doi: 10.1002/ hbm.22567.

24. Destrieux C, Fischl B, Dale A et al. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. Neuroimage 2010; 53(1): 1– 15. doi: 10.1016/ j.neuroimage.2010.06.010.

25. Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E et al. Whole brain segmentation: Automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 2002; 33(3): 341– 355. doi: 10.1016/ S0896-6273(02)00569-X.

26. Williams JB, Kobak KA. Development and reliability of a structured interview guide for the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (SIGMA). Br J Psychiatry 2008; 192(1): 52– 58. doi: 10.1192/ bjp.bp.106.032532.

27. Ustohal L, Prikryl R, Kucerova HP et al. Emotional side effects after high-frequency rTMS of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in an adult patient with ADHD and comorbid depression. Psychiatr Danub 2012; 24(1): 102– 103.

28. Padberg F, Juckel G, Prässl A et al. Prefrontal cortex modulation of mood and emotionally induced facial expressions: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13(2): 206– 212. doi: 10.1176/ jnp.13.2.206.

29. Pascual-Leone A, Catalá MD, Pascual-Leone Pascual A. Lateralized effect of rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation of the prefrontal cortex on mood. Neurology 1996; 46(2): 499– 502. doi: 10.1212/ WNL.46.2.499.

30. Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry 2007; 4(7): 28– 37.

31. Barnow S, Völker KA, Möller B et al. Neurophysiological correlates of borderline personality disorder: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 65(4): 313– 318. doi: 10.1016/ j.biopsych.2008.08.016.

32. Speer AM, Kimbrell TA, Wassermann EM et al. Opposite effects of high and low frequency rTMS on regional brain activity in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48(12): 1133– 1141. doi: 10.1016/ S0006-3223(00)01065-9.

33. Dockx R, Baeken C, Duprat R et al. Regional cerebral blood flow changes after accelerated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the canine frontal cortex. [abstract]. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2015; 42 (Suppl 1): S290– S290.

34. Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ et al. Development and validation of the Minnesota borderline personality disorder scale. Assessment 2011; 18(2): 234– 252. doi: 10.1177/ 1073191111398320.

35. Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Limberger MF et al. The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology 2009; 42(1): 32– 39. doi: 10.1159/ 000173701.

36. Kedzior KK, Reitz SK, Azorina V et al. Durability of the antidepressant effect of the high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the absence of maintenance treatment in major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trials. Depress Anxiety 2015; 32(3): 193– 203. doi: 10.1002/ da.22339.

37. Demirtas-Tatlidede A, Mechanic-Hamilton D, Press DZ et al. An open-label, prospective study of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the long-term treatment of refractory depression: reproducibility and duration of the antidepressant effect in medication-free patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69(6): 930– 934. doi: 10.4088/ JCP.v69n0607.

38. Haesebaert F, Moirand R, Schott-Pethelaz AM et al. Usefulness of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as a maintenance treatment in patients with major depression. World J Biol Psychiatry 2018; 19(1): 74– 78. doi: 10.1080/ 15622975.2016.1255353.

Labels

Paediatric neurology Neurosurgery Neurology

Article was published inCzech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

2019 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Ketogenic diet – effective treatment of childhood and adolescent epilepsies

- Can we accurately diagnose the dyskinetic form of cerebral palsy? YES

- Sub signum coma – current view of chronic disorders of consciousness

- Chronic subdural haematoma

- Iatrogenesis of patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures – possible solutions

- Genetics of neurodegenerative dementias in ten points – what can a neurologist expect from molecular genetics?

- Mild traumatic brain injury management – consensus statement of the Czech Neurological Society CMS JEP

- Contact heat evoked potentials – impact of physiological variables

- Laboratory efficacy testing of acetylsalicylic acid treatment in secondary prevention of ischemic stroke

- Magnetic resonance imaging showing parietal atrophy of the brain in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation in borderline personality disorder – case series

- TNFα and microRNA-15b expression changes in experimental model of subarachnoid haemorrhage

- A Rasch analysis of the Q-LES-Q-SF questionnaire in a cohort of patients with neuropathic pain

- Oligoclonal IgG and free light chains – comparison between agarose and polyacrylamide isoelectric focusing

- New possibilities of ultrasound in predicting low back pain in adolescent males – pilot study

- Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Mild traumatic brain injury management – consensus statement of the Czech Neurological Society CMS JEP

- Chronic subdural haematoma

- Oligoclonal IgG and free light chains – comparison between agarose and polyacrylamide isoelectric focusing

- Ketogenic diet – effective treatment of childhood and adolescent epilepsies

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career