-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

BCKDH: The Missing Link in Apicomplexan Mitochondrial Metabolism Is Required for Full Virulence of and

The mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle is one of the core metabolic pathways of eukaryotic cells, which contributes to cellular energy generation and provision of essential intermediates for macromolecule synthesis. Apicomplexan parasites possess the complete sets of genes coding for the TCA cycle. However, they lack a key mitochondrial enzyme complex that is normally required for production of acetyl-CoA from pyruvate, allowing further oxidation of glycolytic intermediates in the TCA cycle. This study unequivocally resolves how acetyl-CoA is generated in the mitochondrion using a combination of genetic, biochemical and metabolomic approaches. Specifically, we show that T. gondii and P. bergei utilize a second mitochondrial dehydrogenase complex, BCKDH, that is normally involved in branched amino acid catabolism, to convert pyruvate to acetyl-CoA and further catabolize glucose in the TCA cycle. In T. gondii, loss of BCKDH leads to global defects in glucose metabolism, increased gluconeogenesis and a marked attenuation of growth in host cells and virulence in animals. In P. bergei, loss of BCKDH leads to a defect in parasite proliferation in mature red blood cells, although the mutant retains the capacity to proliferate within 'immature' reticulocytes, highlighting the role of host metabolism/physiology on the development of Plasmodium asexual stages.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 10(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004263

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004263Summary

The mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle is one of the core metabolic pathways of eukaryotic cells, which contributes to cellular energy generation and provision of essential intermediates for macromolecule synthesis. Apicomplexan parasites possess the complete sets of genes coding for the TCA cycle. However, they lack a key mitochondrial enzyme complex that is normally required for production of acetyl-CoA from pyruvate, allowing further oxidation of glycolytic intermediates in the TCA cycle. This study unequivocally resolves how acetyl-CoA is generated in the mitochondrion using a combination of genetic, biochemical and metabolomic approaches. Specifically, we show that T. gondii and P. bergei utilize a second mitochondrial dehydrogenase complex, BCKDH, that is normally involved in branched amino acid catabolism, to convert pyruvate to acetyl-CoA and further catabolize glucose in the TCA cycle. In T. gondii, loss of BCKDH leads to global defects in glucose metabolism, increased gluconeogenesis and a marked attenuation of growth in host cells and virulence in animals. In P. bergei, loss of BCKDH leads to a defect in parasite proliferation in mature red blood cells, although the mutant retains the capacity to proliferate within 'immature' reticulocytes, highlighting the role of host metabolism/physiology on the development of Plasmodium asexual stages.

Introduction

The phylum of Apicomplexa comprises a large number of obligate intracellular parasites that infect organisms across the whole animal kingdom. Two important members of this phylum, Plasmodium spp. and Toxoplasma gondii, are the etiological agents of malaria and toxoplasmosis, respectively. Malaria remains one of the most significant global public health challenges (World Malaria Report 2012, www.who.int), while toxoplasmosis causes severe disease and death in immunocompromised individuals and can lead to complications in development of the foetus if contracted during pregnancy [1].

Both Plasmodium spp and T. gondii invade a range of mammalian cells and replicate within a membrane-enclosed compartment called the parasitophorous vacuole (PV). Residence within the PV provides protection from host cell defence mechanisms, while allowing the rapidly developing parasite stages to access small molecules that can diffuse freely across the PV membrane (PVM) [2], [3]. Both T. gondii replicative forms and Plasmodium blood stages were thought to rely primarily on glucose uptake and glycolysis for generation of ATP and other intermediates required for energy generation and replication [4]–[8], and to lack a canonical, pyruvate-fuelled TCA cycle. In particular, Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes exhibit an extraordinarily high rate of glucose uptake [9] and selective inhibitors of the Plasmodium hexose transporter are cytotoxic [10], [11]. Moreover, genomic and biochemical studies have shown that apicomplexan parasites target their single canonical pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH) to the apicoplast, a non-photosynthetic plastid organelle involved in fatty acid biosynthesis, rather than to the mitochondrion [12]–[14]. The absence of a mitochondrial PDH complex in these parasites suggested that glycolytic pyruvate was not converted to acetyl-CoA in the mitochondrion and further catabolised through the TCA cycle [13]–[15].

In other organisms, lipids and branched chain amino acids (BCAA) can be catabolised in the mitochondrion to generate acetyl-CoA via pathways not dependent on PDH (Fig. 1A). However, Plasmodium spp. lack the enzymes needed for the β-oxidation of fatty acids and BCAA degradation. While T. gondii retained the enzymatic machinery necessary for β-oxidation, these parasites appear to lack a typical mitochondrial acyl-carnitine/carnitine carrier [16], [17]. Moreover, the genes coding for β-oxidation enzymes are apparently not expressed in tachyzoites, although they may be active in oocysts [18]. The possibility that T. gondii tachyzoites rely on host BCAA to generate mitochondrial acetyl-CoA was recently investigated, but disruption of the gene encoding the first enzyme involved in BCAA degradation, branched chain amino acid transferase (BCAT) in tachyzoites presented no phenotypic defect [19]. Together, these studies suggested that there was minimal synthesis and catabolism of acetyl-CoA in the mitochondrion.

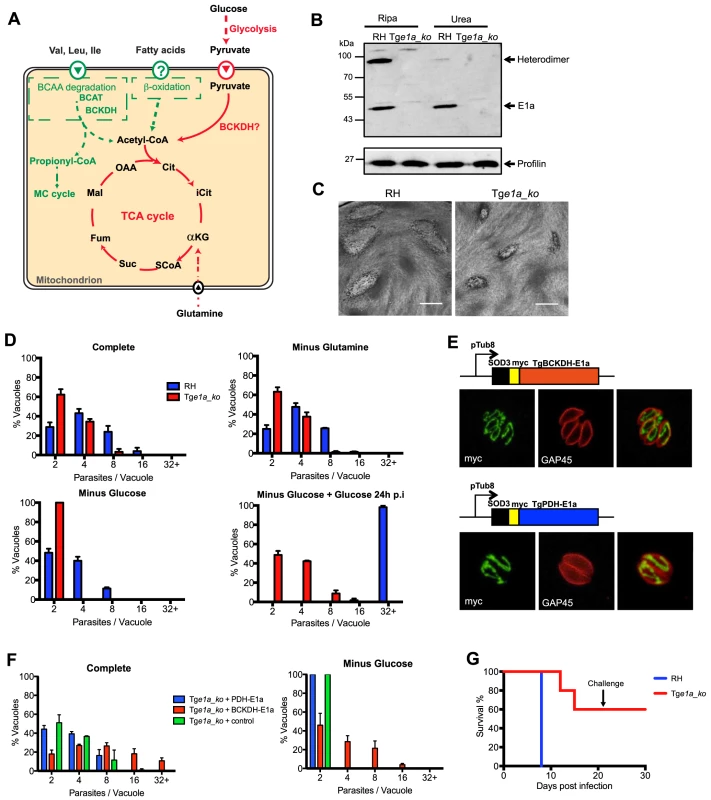

Fig. 1. Toxoplasma gondii BCKDH-complex is required for normal growth and virulence.

(A) Schematic representation of pathways to produce acetyl-CoA in the mitochondrion. In green are pathways specific to T. gondii and in red pathways common to T. gondii and Plasmodium spp. (B) Total lysates from extracellular RHku80_ko (RH) and Tge1a_ko tachyzoites were analysed by Western blot. Expression of BCKDH-E1a was assessed using polyclonal anti-PfBCKDH-E1a antibodies. Detection of profilin was used as loading control. (C) Plaque assays were performed by inoculating HFF monolayers with RH or Tge1a_ko parasites for 7 days. Plaques were revealed by Giemsa staining of HFFs. Scale bar represents 1 mm. (D) Intracellular growth of RH (blue) and Tge1a_ko (red) was assessed after 24 h in complete media, media lacking glutamine, or glucose. Following 24 h of growth in glucose-depleted environment, glucose was added back to the media and rescue of the parasite’s growth was assessed. Data are represented as means ± SD from three independent biological replicates. (E) The apicoplast targeting sequence of TgPDH-E1a (aa 1–225, ABE76506) and mitochondrial targeting sequence of TgBCKDH-E1a (aa 1–73, XP_002366588) were replaced with the mitochondrial transit peptide of the superoxide dismutase 3 (SOD3) and myc-tagged [71] to direct the expression of the fusion protein in the mitochondrion of Tge1a_ko parasites for complementation (creating pTub8-SOD3mycPDHE1a and pTub8-SOD3mycBCKDHE1a respectively). Immunofluorescence assay shows localization of SOD3mycPDHE1a and SOD3mycBCKDHE1a in the single tubular mitochondrion (anti-myc (in green), anti-GAP45 (pellicle marker in red)). (F) Intracellular growth assay at 32 h post transient transfection of Tge1a_ko with pTub8-SOD3mycPDHE1a, pTub8-SOD3mycBCKDHE1a and pTub8-mycNtGAP45 (negative control) in complete media or media depleted in glucose. Data are represented as means ± SD from three independent biological replicates. Only vacuoles containing parasites transiently expressing the transgene were taken into account. Over 200 vacuoles were counted per replicate. (G) CD1 mice were infected with RH (in blue) or Tge1a_ko (in red) tachyzoites (∼15 parasites per mouse) and survival was assessed over 21 days. A challenge with ∼1000 wild-type RH tachyzoites was performed on mice that survived initial infection and survival followed for a further 10 days. Five mice were infected per condition. Several studies have recently led to a reappraisal of this model of carbon metabolism in Apicomplexa. Firstly, detailed 13C-glucose and 13C-glutamine tracer experiments on T. gondii tachyzoite stages showed that carbon skeletons derived from both carbon sources were actively catabolised in a canonical TCA cycle, with the majority of pyruvate entering via acetyl-CoA. Chemical disruption of the aconitase enzyme activity, catalysing an early step in the TCA cycle, completely ablated parasite growth and infectivity in mammalian cells, indicating that the conversion of citrate to isocitrate is important for parasite growth and pathogenesis and that dysregulation of glucose catabolism in the mitochondrion is likely to be lethal [20]. Second, similar studies undertaken in P. falciparum indicate that glucose is further catabolised in the TCA cycle in asexual blood stages [21]–[23], and at a dramatically increased rate in sexual gametocyte stages [21]. A functional, canonical TCA cycle capable of generating reducing equivalents is likely necessary for maintenance of mitochondrial protein transport and the re-oxidation of inner membrane dehydrogenases required for pyrimidine biosynthesis [24]–[28]. The importance of an active respiratory chain in P. falciparum blood stages is highlighted by the sensitivity of this stage to the antimalarial drug atovaquone, which targets respiratory chain complexes [29], and by the increased expression of TCA cycle enzymes in parasites isolated from patients in endemic areas [30], [31]. Atovaquone is also known to kill the rapidly dividing tachyzoite and cyst-forming bradyzoite stages of T. gondii [32].

These studies suggest that the translocation of the conventional mitochondrial PDH to the apicoplast was associated with a new enzyme activity that functionally replaced PDH in regulating TCA cycle metabolism, although the identity of this enzyme remains unknown. The possibility that other mitochondrial dehydrogenases may individually or collectively fill this missing link was raised by the finding that the P. falciparum α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α-KDH) can catalyze the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA in vitro, although slightly less efficiently than PDH [33]. On the other hand, Cobbold et al., proposed that the P. falciparum branched chain ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH), the only enzyme implicated in BCAA degradation retained in the Plasmodium spp., may substitute for PDH based on the finding that catabolism of glucose in the TCA cycle in a P. falciparum PDH mutant was inhibited by oxythiamine, an inhibitor of thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP)-dependent dehydrogenases [22]. However, oxythiamine also inhibits α-KDH (and all other TPP-dependent enzymes), and the enzymatic activity of P. falciparum BCKDH was not tested. The identity of the enzyme(s) that link glycolysis with mitochondrial metabolism, and their functional significance in the normal growth and virulence of these parasites therefore remains an open question.

The genomes of the apicomplexan parasites that contain a functional mitochondrion encode all of the subunits of the BCKDH complex, which include the branched chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase E1 subunits (EC 1.2.4.4), the dihydrolipoyl transacylase E2 subunit (EC 2.3.1.168), and the lipoamide dehydrogenase E3 subunit (EC 1.8.1.4)–(Table S1). The eukaryotic BCKDH and PDH complexes share many structural and enzymatic properties, catalysing analogous reactions in central carbon metabolism where the initial α-ketoacid is decarboxylated by the E1 subunit - a thiamine diphosphate (TPP)-dependent heterotetramer consisting of two α subunits (E1a) and two β subunits (E1b) [34]. Given the functional similarity between these complexes, we have previously postulated that the BCKDH complex could have assumed the function of the mitochondrial PDH in the Apicomplexa [16].

In this study, we provide unequivocal evidence that BCKDH primarily fulfils the function of mitochondrial PDH in both T. gondii and Plasmodium berghei, a rodent model for malaria. P. berghei allows phenotypic evaluation under physiological conditions in vivo and offers the potential to interrogate the whole parasite life cycle from mosquito to mouse. We find that genetic disruption of the BCKDH-E1a subunit in these parasites leads to a block in the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, and global changes in metabolic fluxes, as shown by metabolite profiling and comprehensive 13C-stable isotope labelling approaches. More importantly, the functional disruption of the BCKDH multi-enzyme complex was associated with a growth defect and reduced virulence of T. gondii in mice, while in P. berghei it resulted in strong alteration of intraerythrocytic development and severely diminished virulence in mice. In addition, the absence of BCKDH affects all the vector stages and blocks oocyst development in the mosquito, indicating that this pathway is essential for transmission of the disease.

Results

Toxoplasma gondii BCKDH is required for normal intracellular growth and virulence

Point mutations in human BCKDH-E1a are associated with complete loss of catalytic activity [34], indicating that genetic depletion of this subunit should be sufficient to abrogate BCKDH function. Deletion of the gene coding for the E1a subunit of TgBCKDH was achieved by double homologous recombination (Tge1a_ko) in the RHku80_ko (hereafter termed ‘RH’) background strain, which favours homologous recombination over random integration (Fig. S1A) [35], [36]. Transgenic parasites were cloned and loss of TgBCKDHE1a was demonstrated by genomic PCR (Fig. S1B), while absence of the protein was confirmed by Western blot using cross-reacting anti-P. falciparum E1a antibodies (Fig. 1B). The E1a subunit was detected as a ∼45 kDa and a ∼90 kDa band in Western blots of wild type parasites. The 90 kDa band likely corresponds to the E1a/E1b heterodimer, as the intensity of this band was severely diminished under strong denaturating conditions (Fig. 1B). Neither band was detected in the knockout.

The Tge1a_ko formed smaller plaques in a human foreskin fibroblast (HFF) lytic plaque assay compared to the parental RH strain (Fig. 1C) indicating a reduced ability to infect and/or grow in host cells. Further phenotypic analyses revealed that neither Tge1a_ko tachyzoite invasion nor egress from infected host cells were affected (data not shown) and that the reduction in fitness was due to significantly reduced intracellular growth compared to RH parasites, as monitored by the reduced number of parasites per vacuole established by Tge1a_ko after 24 h (Fig. 1D). This phenotype was exacerbated when infected HFF were cultivated in the absence of glucose in a reversible fashion, while removal of glutamine did not aggravate this defect (Fig. 1D).

To validate that the phenotypes observed in Tge1a_ko are only due to the loss of the E1a subunit of BCKDH, we targeted a second copy of the E1a subunit where the N-terminal mitochondrion targeting signal was replaced by the mitochondrial transit signal of TgSOD3 (SOD3mycBCKDH-E1a, Fig. 1E) in Tge1a_ko parasites. In addition, we attempted to complement Tge1a_ko parasites by targeting the product of a second copy of the TgPDH-E1a subunit to the mitochondrion via replacement of its bipartite targeting signal with the mitochondrial transit signal of TgSOD3 (SOD3mycPDH-E1a, Fig. 1E). TgPDH-E1a and TgBCKDH-E1a show significant similarity by sequence alignment (∼25%) and the catalytic residues are clearly conserved between the two subunits (Fig. S3A). The mitochondrial SOD3mycPDH-E1a was unable to rescue the intracellular growth defect of Tge1a_ko parasites while complementation with SOD3mycBCKDH-E1a restored the growth of Tge1a_ko (Fig. 1F). This highlights a lack of permissiveness to interchange subunits between the different α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes but moreover confirmed that the phenotypes observed with Tge1a_ko are solely due to the absence of BCKDH activity.

To further examine whether BCKDH is required for virulence, mice were injected intraperitoneally with ∼15 RH or Tge1a_ko tachyzoites. The inoculation of virulent RH parasites resulted in acute toxoplasmosis in all mice after 8 days leading to their culling. In contrast, 3 out of 5 mice infected with Tge1a_ko parasites remained alive after 21 days (Fig. 1G). The surviving mice had seroconverted and were resistant to subsequent challenge with ∼1,000 RH parasites (Fig. 1G). Taken together, these results establish that the BCKDH complex is implicated in glucose catabolism and is important for both parasite fitness in vitro and virulence in vivo.

BCKDH is required for catabolism of pyruvate in the TCA cycle of T. gondii

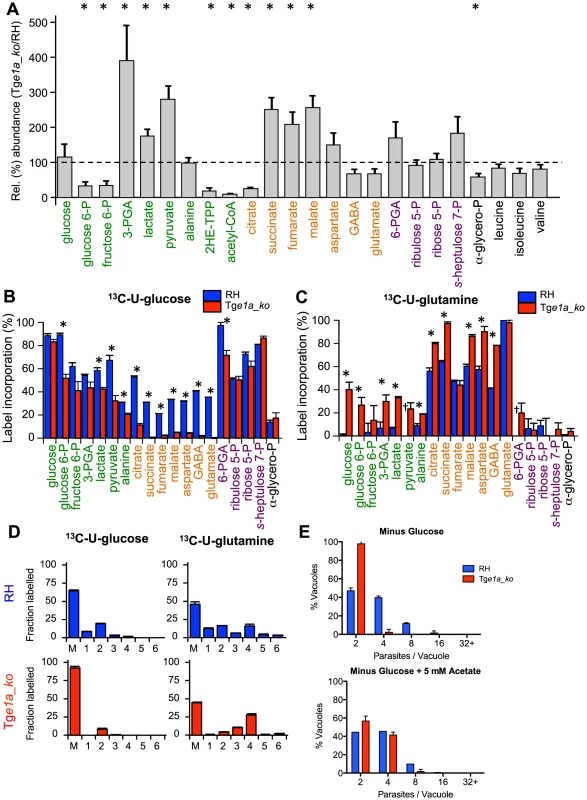

To investigate the underlying basis of the intracellular growth defect in the BCKDH mutant, T. gondii RH and Tge1a_ko tachyzoites were cultivated in HFF and metabolite levels in egressed tachyzoites determined by both GC-MS and LC-MS (Fig. 2A). Significant differences were observed in the levels of several glycolytic and early TCA cycle intermediates in Tge1a_ko tachyzoites, compared to the RH control strain. This included a 4 - to 10-fold decrease in 2-hydroxyethyl-TPP (the intermediate in synthesis of acetyl-CoA from pyruvate), acetyl-CoA, and citrate, and a 2 - to 4-fold increase in 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA), pyruvate and lactate (Fig. 2A). These data are consistent with a defect in the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA and citrate as well as an increased flux to lactate production.

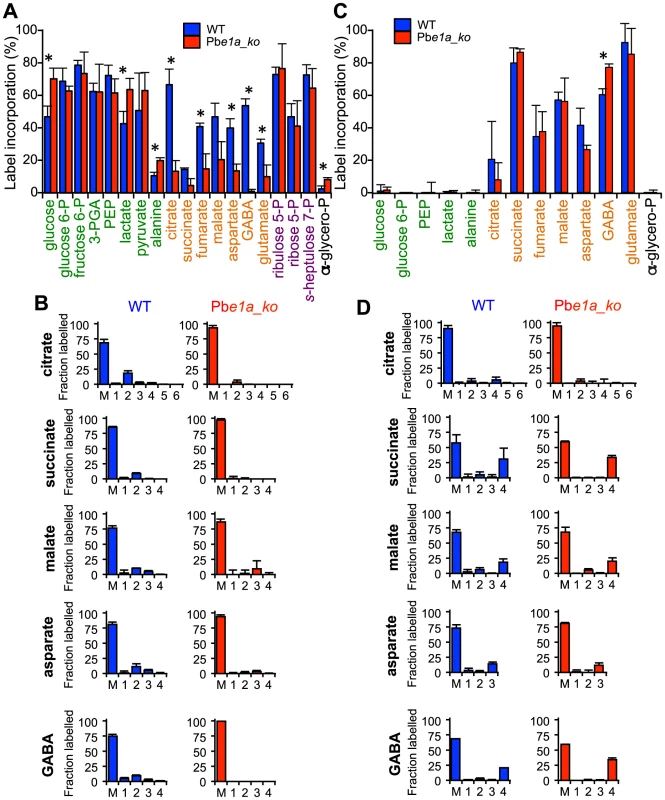

Fig. 2. BCKDH is required for conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA and catabolism of glucose in the mitochondrion.

Freshly egressed RH and Tge1a_ko tachyzoites were labelled with 13C-U-glucose or 13C-U-glutamine for 4 h. Abundance and label incorporation were assessed by GC-MS and LC-MS. (A) Relative (%) abundance of selected metabolites in the TgE1a_ko mutant parasites. Bars represent abundance of metabolites in Tge1a_ko cells compared with a parental (RH) control. The dashed line refers the abundance of the metabolite in the parental control (‘100%’). 2HE-TPP refers to 2-hydroxyethyl-thiamine pyrophosphate, the stable intermediate specifically generated by pyruvate dehydrogenase activity. 2HE-TPP and acetyl-CoA were measured by LC-MS while other metabolites were measured by GC-MS (B) 13C-glucose and (C) 13C-glutamine incorporation into central carbon metabolites in RH (blue) and Tge1a_ko (red) tachyzoites, where label incorporation is the fraction of molecules of that metabolite containing one or more 13C carbons (after correction for natural abundance). In A, B and C metabolites are colour-coded by metabolic pathway; central carbon metabolism, green; TCA cycle and associated amino acids, orange; PPP, purple; other, black. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3–6). Significance as determined by t-test is shown (corrected for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method), with significant (p-values of 0.05) differences indicated by an asterisk. † indicates metabolite not detected. (D) Mass isotopologue abundances of citrate generated in 13C-glucose and 13C-glutamine-fed RH and Tge1a_ko tachyzoites. ‘M’ indicates the monoisotopic mass containing no 13C atoms. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3). (E) Intracellular growth of RH (blue) and Tge1a_ko (red) was assessed after 24 h in medium depleted of glucose complemented or not with 5 mM exogenous acetate. Data are represented as means ± SD from three independent biological replicates. To confirm that Tge1a_ko parasites have a defect in acetyl-CoA synthesis, freshly egressed RH and Tge1a_ko tachyzoites were metabolically labelled with 13C-U-glucose. The intermediates in glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and the TCA cycle were strongly labelled in RH parasites (Fig. 2B). Citrate isotopomers were generated containing +2, +3 and +4 13C carbons, indicative of entry of both 13C2-acetyl-CoA and 13C3-oxaloacetate derived from pyruvate into the TCA cycle of RH parasites (Fig. 2D). In contrast, the labelling of acetyl-CoA and TCA cycle intermediates, including citrate and the C4 dicarboxylic acids, were dramatically reduced in Tge1a_ko (Fig. S2A, 2B and 2D), suggesting that loss of BCKDH is associated with a block in entry of glucose-derived pyruvate into the TCA cycle. This was supported by complementary labelling with 13C-U-glutamine, which revealed equivalent or elevated enrichment of label in all TCA cycle intermediates in Tge1a_ko compared to RH parasites (Fig. 2C). The predominant citrate isotopologue generated in 13C-glutamine-fed Tge1a_ko had +4 13C atoms (Fig. 2D) indicating that glutamine-derived 13C4-oxaloacetate combines with a residual source of unlabelled acetyl-CoA to allow citrate synthesis. This could reflect low level capacity of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase to convert pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, or more likely, the conversion of mitochondrial-produced 13C4-oxaloacetate to citrate in the cytosol via the ATP-citrate lyase or the second putative citrate lyase (TGME49_203110, www.toxodb.org) present in the genome of T. gondii. Interestingly, significant labelling of glycolytic intermediates and hexose-phosphate was detected in 13C-glutamine-fed Tge1a_ko tachyzoites, which was absent in wild type parasites (RH) (Fig. 2C). Collectively, these findings show that the BCKDH is required for the conversion of pyruvate to mitochondrial acetyl-CoA and operation of a cyclical TCA cycle. In the absence of BCKDH, the continued production of C4 dicarboxylic acids derived from glutamine by the oxidative TCA cycle leads to increased gluconeogenic fluxes despite the fact that these parasites continue to utilize glucose and have a high glycolytic flux.

To investigate whether BCKDH is also required for catabolism of branched chain amino acids (BCAA), RH and Tge1a_ko were labelled with 13C-U-leucine, 13C-U-isoleucine and 13C-U-valine. An untargeted metabolome-wide isotope analysis detected no significant 13C-enrichment in TCA cycle intermediates, despite detecting efficient uptake of branched chain amino acids and conversion to the respective 13C-labeled branched chain keto acids (data not shown). No significant differences in the steady state levels of leucine, isoleucine or valine were detected between the parental and knock out strains (Fig. 2A). Together these data strongly suggest that mitochondrial acetyl-CoA is not derived from BCAAs under normal growth conditions (Fig. S2B).

To determine whether the role of BCKDH in acetyl-CoA production could be by-passed by addition of exogenous acetate, fibroblasts infected with Tge1a_ko were cultivated in media with or without acetate. Supplementation of the medium with acetate led to a partial but significant rescue of the severe growth defect observed in the absence of glucose (Fig. 2E). This result is consistent with BCKDH having a role in acetyl-CoA production and suggests some redundancy in the functions of BCKDH and acetyl-CoA synthetase in generating mitochondrial and/or cytoplasmic pools of acetyl-CoA.

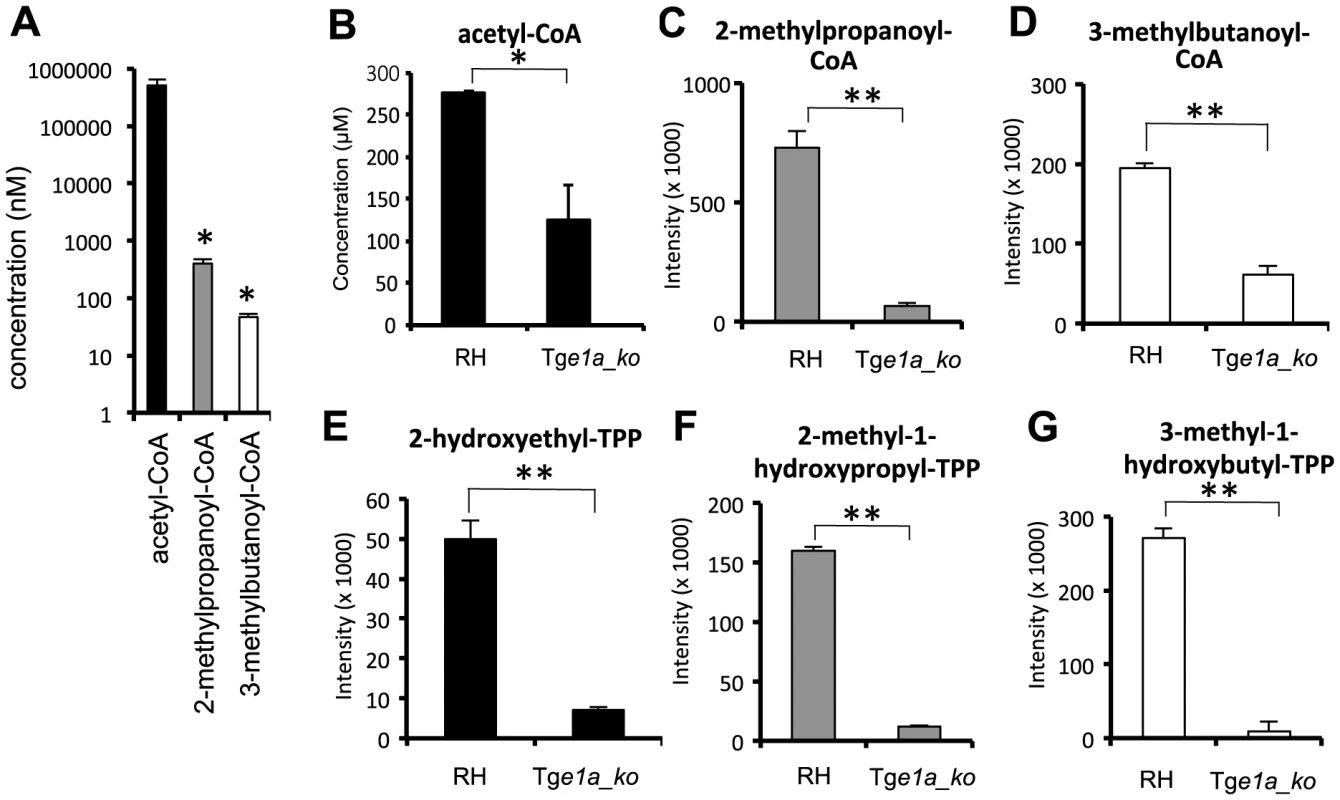

BCKDH is a PDH-like enzyme

In vitro enzyme assays were performed to investigate the substrate selectivity of T. gondii BCKDH. As attempts to express an active, recombinant BCKDH complex were unsuccessful, enzyme assays were performed on whole cell lysates from RH and Tge1a_ko parasites. PDH activity was detected when cell lysates were incubated with 0.5 mM pyruvate in the presence of cofactors, with over two-fold higher concentration of acetyl-CoA production observed in RH (276 µM) than Tge1a_ko (124 µM) extracts, confirming a role of BCKDH in acetyl-CoA production (Fig. 3B) (p<0.05). The significant level of background PDH-like activity observed in Tge1a_ko extracts is likely mediated by the apicoplast PDH or mitochondrial α-KDH complexes. Minimal production of the branched chain acyl-CoAs, 3-methylpropanoyl-CoA (128 nM) and 3-methylbutanoyl-CoA (below limit of quantitation; LOQ = 5 nM), was detected following incubations with their respective substrates, 4-methyl-2-oxopentanoate and 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate. Branched chain acyl-CoA formation was significantly lower in Tge1a_ko compared to RH extracts (Fig. 3C–D), suggesting BCKDH does indeed possess classical BCKDH-like activity. However, accurate quantification of acyl-CoA products from assays with higher substrate concentrations (2 mM) confirmed that the BCKDH-like activity was 1000 - to 10,000-fold lower than the PDH-like activity (Fig. 3A), suggesting that this enzyme functions primarily as a PDH in vivo. Interestingly, the hydroxyalkyl-TPP intermediates for all three substrates were detected in a BCKDH-dependent manner (Fig. 3E–G).

Fig. 3. BCKDH possesses PDH activity.

(A) In vitro enzyme activity indicates a low level of classical branched chain keto-acid dehydrogenase activity and extensive pyruvate dehydrogenase activity in RH T. gondii cell lysates. Concentrations (mean ± SD) of acetyl-CoA (black), 2-methylpropanoyl-CoA (grey), and 3-methylbutanoyl-CoA (white columns), were measured following incubation of RH lysates with 2 mM pyruvate (black), 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate (grey) or 4-methyl-2-oxopentanoate (white columns), respectively. (B) concentration of acetyl-CoA following in vitro incubation of RH or Tge1a_ko extracts with 0.5 mM pyruvate (C–D) Relative abundance of acyl-CoA products following in vitro incubation of RH or Tge1a_ko extracts with 0.5 mM (C) 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate or (D) 4-methyl-2-oxopentanoate. (E–G) Relative abundance of hydroxyalkyl-TPP intermediates following incubation of RH or Tge1a_ko lysates with 0.5 mM (E) pyruvate, (F) 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate or (G) 4-methyl-2-oxopentanoate. Metabolite intensity (y-axis) is measured by LC-MS peak area (mean ± SD; n = 2). Significance as determined by t-test is shown, with p-values of <0.05 and <0.01 indicated by an asterisk and double asterisk, respectively. BCKDH activity is required for correct intraerythrocytic development of P. berghei

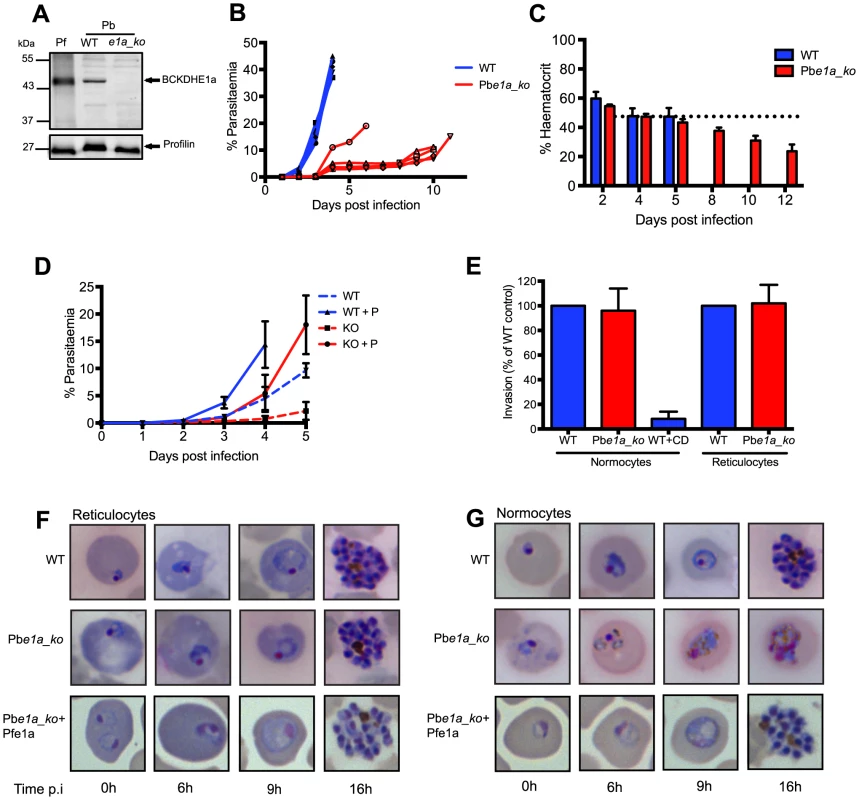

To determine whether BCKDH has a similar role in malaria parasites, a P. berghei mutant lacking the BCKDH E1a subunit was generated by double homologous recombination (Pbe1a_ko) (Fig. S4A). Several independent positive transgenic pools were obtained after drug cycling. However, their slow growth hampered the cloning of the mutants by limiting dilution in wild type immunocompetent CD1 mice. Since the parasites seemed to exhibit a severe fitness defect that might lead to clearance of the infection by the mouse immune system, we switched to immunodeficient RAG-1 -/ - mice for cloning purposes [37]. Loss of expression of Pbe1a in the clonal Pbe1a_ko line from these mice, was demonstrated by genomic PCR and Western blot analysis (Fig. S4D and 4A). Strikingly, mice infected with 15×106 Pbe1a_ko parasites had constant low parasitaemias (5–15% over 10 days), while infection with WT parasites led to an exponential rise in parasitaemia (up to 45% after 4 days), leading to culling due to illness (Fig. 4B). Despite having much lower parasitaemias, mice infected with Pbe1a_ko parasites developed symptoms of severe anaemia and were culled 10–12 days post-infection (Fig. 4B). The haematocrit level between the mice infected with WT or Pbe1a_ko was comparable during the first five days of infection (Fig. 4C). Haematocrit levels continuously decreased over the subsequent 7 days in the Pbe1a_ko-infected mice (Fig. 4C), consistent with the observed anaemia in these animals.

Fig. 4. BCKDH is required for growth of Plasmodium berghei in mature RBCs.

(A) Total lysates from a mixed population of parasitic stages for P. falciparum 3D7 (Pf), Pb wild type (WT) and Pbe1a_ko were analysed by Western blot. Expression of BCKDH-E1a (shown by the arrow) was assessed using cross-reacting anti-PfBCKDH-E1a antibodies. Profilin was used as loading control. (B) Parasitaemia was followed daily in mice infected with WT (blue line) or Pbe1a_ko (red line). Each line corresponds to the parasitaemia of one mouse. 5 mice were infected per condition. (C) Haematocrit was followed over the course of infection in mice infected with WT (blue) or Pbe1a_ko (red). Corresponding parasitaemia levels of this experiment are shown in Fig. S3B. The dotted line represents the mean haematocrit level of uninfected control mice followed throughout the experiment. Data show mean ± SD from 4 mice per condition. (D) Parasitaemia was followed daily in mice pre-treated (full lines) or not (dotted lines) with phenylhydrazine to induce reticulocytosis 3 days prior infection with parasites. Mice were infected with 5×106 WT (blue line) or Pbe1a_ko (red line) parasites. 5 mice were infected per condition and lines represent mean parasitaemia ± SD. (E) Invasion of Pbe1a_ko (red) compared to WT (blue). Vybrant Green-labeled purified schizonts were incubated with DDAO-SE-labeled purified normocytes or reticulocytes, and free merozoites were allowed to invade. Parasitaemia in the DDAO-SE-labeled target population was determined by flow cytometry. Invasion efficiency was determined as a percentage of the WT control parasites. Cytochalasin D (CD)-treated schizonts were used as a negative control. Data are represented as mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates. (F) Giemsa-stained blood smears showing normal development of WT, Pbe1a_ko and complemented Pbe1a_ko+Pfe1a parasites to the schizont stage in purified reticulocytes. Parasites were cultured in vitro for the times indicated. (G) Giemsa-stained blood smears showing development of the different strains within purified normocytes. WT parasites mature normally from ring to schizont stage while Pbe1a_ko degenerate rapidly. Complemented Pbe1a_ko+Pfe1a restored the ability of Pbe1a_ko to develop within normocytes. Parasites were cultured in vitro for the times indicated. To understand why the haematocrit level decreased despite relatively low parasitaemia, parasite distribution was further investigated in the different red blood cell types. In wild type parasite infected mice, parasites could be found both within reticulocytes as well as in normocytes. In contrast, the majority of Pbe1a_ko parasites were present within reticulocytes throughout the course of infection. To assess the importance of this apparent cell tropism, we induced reticulocytosis in mice with phenylhydrazine prior to infection. In mice infected with wild type, parasitaemia increased as expected and phenylhydrazine pre-treatment slightly accentuated the growth of the parasites. Pre-treatment of mice with phenylhydrazine rescued significantly the growth defect observed with Pbe1a_ko (although not to wild type levels as reticulocytes maturate into normocytes over the course of infection) while in mice not pre-treated the parasitaemia levels remained low throughout the 5 days of infection supporting the observation that Pbe1a_ko seemed to preferentially infect reticulocytes (Fig. 4D). This differential distribution is not explained by an invasion defect of the Pbe1a_ko parasites for normocytes as shown in (Fig. 4E). Indeed, we observed no difference in invasion efficiency between WT and Pbe1a_ko parasites when using purified normocytes and reticulocytes as target host cells.

In vitro maturation was examined following in vitro invasion of purified normocytes or reticulocytes. This selective distribution appears to be due to rapid loss of viability of Pbe1a_ko in the normocytes. Specifically, WT parasites developed to the schizont stage in both reticulocytes and normocytes (Fig. 4F and 4G, respectively), whereas Pbe1a_ko parasites developed normally in reticulocytes (Fig. 4F), but rapidly degenerated within normocytes (Fig. 4G). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that a functional BCKDH complex is required for the development of P. berghei in mature erythrocytes. The abortive infections of normocytes are most likely eliminated from the circulation by the spleen and liver, resulting in the lower parasitaemia and protracted course of infection of the mutant.

To confirm that the observed attenuation phenotype is solely attributable to the deletion of the PbBCKDH-E1a gene, Pbe1a_ko parasites were complemented with a copy of the P. falciparum BCKDH-E1a gene, PfE1a (Fig. S4C). Pbe1a_ko+PfE1a parasites were obtained after several passages in mice with intermittent drug selection. Integration of the complementation plasmid and PfE1a protein expression were confirmed by genomic PCR (Fig. S4D) and Western blot analyses (Fig. S4E). Complementation with PfE1a restored the ability of these parasites to complete their development in mature erythrocytes (Fig. 4F and 4G) and their growth rate in vivo was comparable to the parental WT strain (Fig. S4F). These results also indicate that the E1a subunit from P. falciparum can assemble with the P. berghei subunits to form a functional BCKDH multi-enzyme complex.

BCKDH acts as a PDH-like complex in the mitochondrion of P. berghei

To determine whether the BCKDH complex fulfils the function of a mitochondrial PDH in the P. berghei asexual blood stages, ring/early trophozoite stages of WT and Pbe1a_ko parasite-infected RBCs (iRBCs) were matured to schizonts in vitro and labelled with 13C-U-glucose or 13C-U-glutamine over the final 5 h of maturation. Schizont-iRBCs were purified and the labelling of intracellular metabolite pools determined by GC-MS. Intermediates in glycolysis, the PPP and TCA cycle were highly enriched when RBCs infected with WT parasites were labelled with 13C-glucose (Fig. 5A and S5A) while in uninfected RBCs, 13C-labelling from glucose was only detected in the glycolysis and PPP metabolites (Fig. S5A). After 5 h labelling, the major isotopologues of citrate in WT iRBCs contained two 13C-carbons, reflecting the incorporation of 13C2-acetyl-CoA into citrate after one round of the TCA cycle (Fig. 5B). While a similar labelling of glycolytic and PPP intermediates was observed in Pbe1a_ko-iRBC, incorporation into TCA intermediates and associated amino acids was greatly diminished in the Pbe1a_ko compared to WT iRBCs (Fig. 5A, 5B and S5A). It is notable that +3 isotopologues of malate and aspartate (a proxy of oxaloacetate) were still detected in 13C-glucose-fed parasites, reflecting continued conversion of pyruvate to malate (via oxaloacetate) by the action of PEPC (Fig. 5B), as recently observed [23]. These findings demonstrate that BCKDH is required for the mitochondrial catabolism of glucose by conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA in P. berghei blood stage parasites.

Fig. 5. P. berghei parasites lacking the BCKDH-E1a subunit exhibit a perturbed TCA cycle.

Cultures containing ring/early-trophozoite WT and Pbe1a_ko P. berghei-infected RBCs were allowed to mature to schizonts and labelled with 13C-U-glucose or 13C-U-glutamine for 5 hr. Label incorporation was assessed by GC-MS. (A) Total 13C-glucose-derived label incorporation into central carbon metabolism metabolites in WT (blue) and Pbe1a_ko (red) P. berghei-infected RBCs, where label incorporation is the fraction of molecules of that metabolite containing one or more 13C carbons (after correction for natural abundance). Metabolites are colour-coded by metabolic pathway; central carbon metabolism, green; TCA cycle and associated amino acids, orange; PPP, purple; other, black. Error bars represent standard deviation (N = 4). Significance as determined by t-test is shown (corrected for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method), with significant (p-value<0.05) differences indicated by an asterisk. † indicates metabolite not detected. (B) Mass isotopologue distributions of the TCA intermediates shown in Panel A. The x-axis indicates the number of 13C-atoms in each metabolite (‘M’ indicates the monoisotopic mass containing no 13C atoms). The y-axis indicates fractional abundance of each isotopologue when labelled with 13C-U-glucose (present in the culture medium at ∼50%). Error bars indicate standard deviation (N = 4). (C, D) As for A and B, but after labelling with 13C-U-glutamine (present in the culture medium at ∼98%). Importantly, both wild type and Pbe1a_ko-infected RBC catabolized 13C-U-glutamine in a canonical TCA cycle (Fig. 5C and 5D), as has recently been shown to occur in P. falciparum [21]–[23]. However, in contrast to the situation in T. gondii, no evidence for increased gluconeogenesis in the Pbe1a_ko-infected RBC was observed, consistent with the absence of key gluconeogenic enzymes in these parasites [10].

As anticipated, label derived from 13C-U-leucine was not incorporated into TCA cycle intermediates in either WT, Pbe1a_ko-infected RBC, or uninfected RBCs (Fig. S5B), indicating that PbBCKDH does not catabolise α-ketoacids generated from BCAA and consistent with the absence of BCAA-specific aminotransferase (BCAT) in the malaria parasite genomes (Table S1).

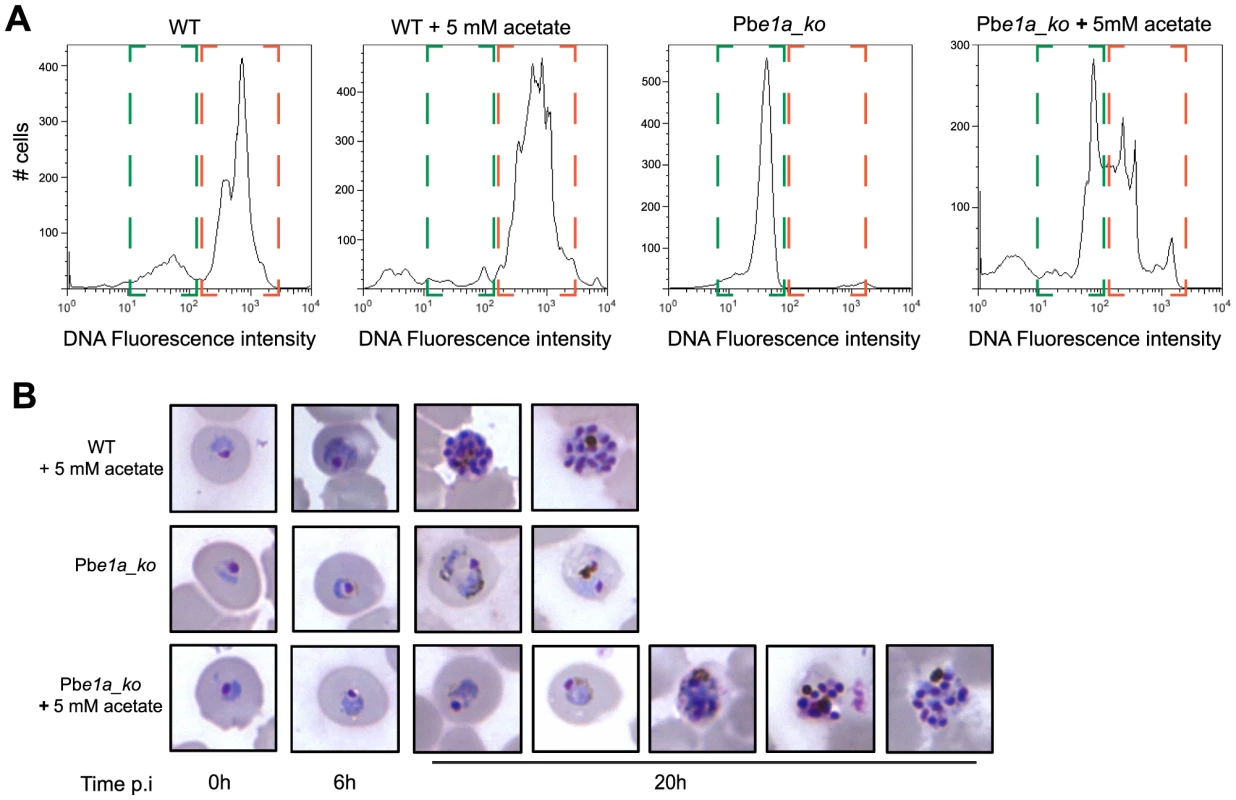

To assess whether differences in the acetyl-CoA levels of Pbe1a_ko, via conversion of acetate to acetyl-CoA from the acetyl-CoA synthetase, could be responsible for the reticulocyte tropism that is observed, we followed in vitro maturation of wild type and Pbe1a_ko parasites within normocytes in presence or not of exogenous acetate. Pbe1a_ko parasite growth in normocytes was partially restored by supplementation of the medium with acetate (Fig. 6A–B and S6A), indicating that the presence of acetate in reticulocytes could be one of the factors contributing to the ability of Pbe1a_ko parasites to survive and develop within this cell type but not within normocytes.

Fig. 6. Acetate complementation of P.berghei BCKDH null mutants.

(A) Following in vitro invasion of normocytes with WT or Pbe1a_ko, parasites were allowed to mature in vitro for 20 h in media supplemented or not with 5 mM acetate. Replication of DNA content was taken as measure of parasite maturation. DNA was labelled using Vybrant DyeCycle Ruby Stain and fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. Highlighted in green is the ring/parasites degenerated early in their development fraction while trophozoite/schizont stage iRBCs are highlighted in orange. The results of two other biological replicate can be found in Fig. S6. (B) Giemsa-stained blood smears showing development of the different strains within normocytes in medium complemented or not with 5 mM acetate. WT mature from ring to schizonts within normocytes in presence of 5 mM acetate. Pbe1a_ko degenerate rapidly within normocytes in normal culture conditions while complementation with 5 mM acetate rescues partially their viability and maturation. Figure shows the various stages of Pbe1a_ko maturation that can be observed over the in vitro culture period. Parasites were cultured in vitro for the times indicated. BCKDH has roles in P. berghei sexual development and oocyst maturation

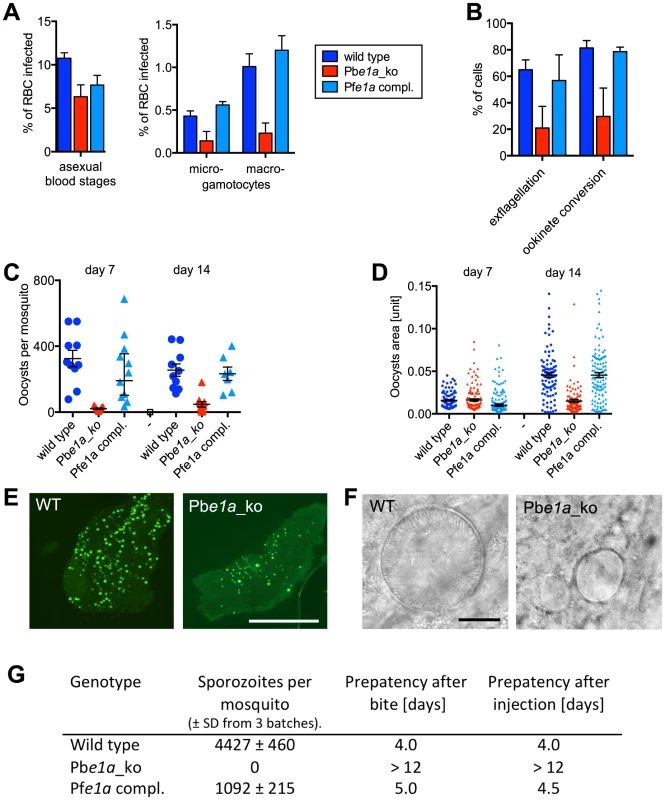

We next assessed the effect of deleting the BCKDH-E1a gene on sexual development and mosquito transmission of P. berghei. To minimise a potential indirect effect of the attenuated growth of the Pbe1a_ko mutant on gametocyte numbers, mice were injected with phenylhydrazine two days before infection, inducing mild anaemia and increased reticulocytosis. As a result, a similar parasitaemia was obtained for all strains on day 3 post-infection (Fig. 7A). The numbers of morphologically mature female (macro-) and male (micro-) gametocytes were lower in Pbe1a_ko parasites than in either wild type or PfE1a complemented clones (Fig. 7A). The small number of microgametocytes in the Pbe1a_ko clone had a considerably reduced capacity to differentiate (exflagellate) into microgametes when stimulated by xanthurenic acid in vitro. Possibly as a result, the ability of macrogametocytes to convert into ookinetes upon activation in vitro was also reduced (Fig. 7B). Absence of BCKDH thus reduced both the numbers of morphologically mature gametocytes and their ability to develop in vitro.

Fig. 7. Role of BCKDH during sexual development and in mosquito stages of P. berghei.

(A) Asexual parasitaemia and male (micro-) and female (macro-) gametocytaemia in the peripheral blood of mice 3 days post infection with 1×107 parasites i. p. Error bars show standard deviations from 3 mice. (B) Developmental capacity of gametocytes in vitro measured from the same infections shown in panel A. The relative ability of microgametocytes to release microgametes was assessed by counting exflagellation centres in a haemocytometer 15 min after addition to activating medium. The ability of activated macrogametocytes to become fertilised and convert to ookinetes was assessed by quantifying round and ookinete-shaped parasites following life staining of the surface marker P28. Colour code as in panel A; error bars show standard deviations. (C) Oocyst numbers on the midguts of individual A. stephensi mosquitoes on different days after feeding on three infected mice per mutant. Geometric means and 95% confidence intervals are also shown. (D) Sizes of individual oocysts from infected midguts at different days after infection. Black lines show geometric means and 95% confidence intervals. (E) Fluorescence micrographs of representative A. stephensi midguts dissected 14 days after feeding on wild type and mutant parasites expressing GFP. Scale bar = 0.5 mm. (F) Phase contrast images of representative oocysts. Scale bar = 10 µm. (G) Sporozoite numbers per mosquito as determined from 3 batches of 10 dissected salivary glands. Transmission from mosquito to mice was examined by measuring the prepatent period in 2 mice per group after bites from ∼20 mosquitoes or intraperitoneal injection of homogenates from 10 pairs of salivary glands. Data shown in all panels are representative of two independent experiments each performed with three infected mice per parasite line. To assess the role of BCKDH in transmission, Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes were allowed to feed on infected mice. Consistent with the in vitro data, the Pbe1a_ko mutant gave rise to a considerably reduced number of oocysts per infected mosquito midgut, an effect that was fully reversed by complementation with the PfE1a gene (Fig. 7C). Importantly, after day 7 of infection, Pbe1a_ko showed a marked inability to increase in size (Fig. 7D and 7E), and the mutant cysts invariably failed to undergo sporogony (Fig. 7F). Pbe1a_ko-infected mosquitoes contained no sporozoites in their salivary glands on day 21 post infection, neither were they able to re-infect mice, either by bite or intravenous injection of disrupted salivary glands (Fig. 7G). Taken together, these data demonstrate that in addition to its role for blood stage development in normocytes, BCKDH is necessary for normal gametocyte production and fitness, and that BCKDH is essential for oocysts to mature and undergo sporogony.

Discussion

Using a combination of genetic and metabolomic approaches, we show that the BCKDH complex not only substitutes for the loss of mitochondrial PDH in Apicomplexa, but is also required for normal growth and virulence of T. gondii and P. berghei. While T. gondii and Plasmodium spp. were thought to depend on glycolysis for energy, recent studies have highlighted the potential importance of oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial metabolism [27], [28], [30], [38]. Indeed 13C-glucose and 13C-glutamine labelling studies have recently confirmed the operation of a canonical TCA cycle in both T. gondii and P. falciparum [20], [21]. A critical question raised by these studies concerns the identity of the enzyme(s) that feed carbon skeletons into the TCA cycle. In most organisms, the operation of the TCA cycle is dependent on production acetyl-CoA from pyruvate, via the catalytic activity of a mitochondrial PDH complex. Apicomplexa have a canonical PDH, but this complex is targeted to the apicoplast, suggesting that other enzymes fulfil the function of the PDH in the mitochondrion [13]–[15]. Recent studies have raised the possibility that mitochondrial acetyl-CoA could be generated from glycolytic pyruvate via one of the other TPP-dependent mitochondrial dehydrogenases [22], [33]. However, direct evidence for involvement of either BCKDH or α-KDH, or another uncharacterized dehydrogenase has not been obtained.

Here, we have generated T. gondii and P. berghei BCKDH null mutants by reverse genetics and demonstrated loss of mitochondrial glucose metabolism. Deletion of the BCKDH-E1a gene from T. gondii and P. berghei was non-lethal, but in each case led to a marked reduction in growth rate and impacted on parasite virulence in mice. Metabolite profiling coupled with 13C-U-glucose labelling established that BCKDH catalyses the conversion of mitochondrial pyruvate to 13C2-acetyl-CoA and fuels a canonical TCA cycle both in T. gondii and P. berghei. Specifically, deletion of BCKDH-E1a was associated with loss of labelling of 13C2-acetyl-CoA and +2 13C-isotopologues of other TCA cycle intermediates. In T. gondii, loss of the BCKDH-E1a gene also led to significant decreases in 2-hydroxyethyl-TPP, the intermediate in acetyl-CoA production from pyruvate, as well as acetyl-CoA and citrate. Conversely, pyruvate levels increased in a manner consistent with this substrate no longer being consumed by the enzyme. In vitro analysis of α-ketoacid dehydrogenase activity in T. gondii extracts demonstrated some affinity for both pyruvate and branched-chain keto-acids, but with a high selectivity for the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA compared to the minimal conversion of branched chain keto-acids to their respective branched chain acyl-CoA products. Taken together, our data demonstrate that the apicomplexan BCKDH complex has been repurposed to function as a PDH and allow the further oxidation of pyruvate in a canonical TCA cycle.

Sequence alignment analysis of the T. gondii and P. berghei E1a with other BCKDH-E1a (Fig. S3B and S3C) and E1b subunits failed to ascertain whether active site residue substitutions can account for substrate versatility [39], [40] and further structural characterization will be required to refine our understanding of the substrate specificity of this class of enzyme. However, these results account for the retention of BCKDH genes in Plasmodium spp., despite the loss of other genes involved in BCAA degradation. They are also consistent with the presence of the two genes coding for the subunits of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier recently described in yeast [41], [42] (Table S1). Interestingly, more distantly related members of the Alveolata, such as dinoflagellates also lack a conventional mitochondrial PDH complex, but retain a BCKDH [17], suggesting that the repurposing of BCKDH evolved early in the evolution of this group and is likely to be conserved in all members of this group that contain a functional TCA cycle.

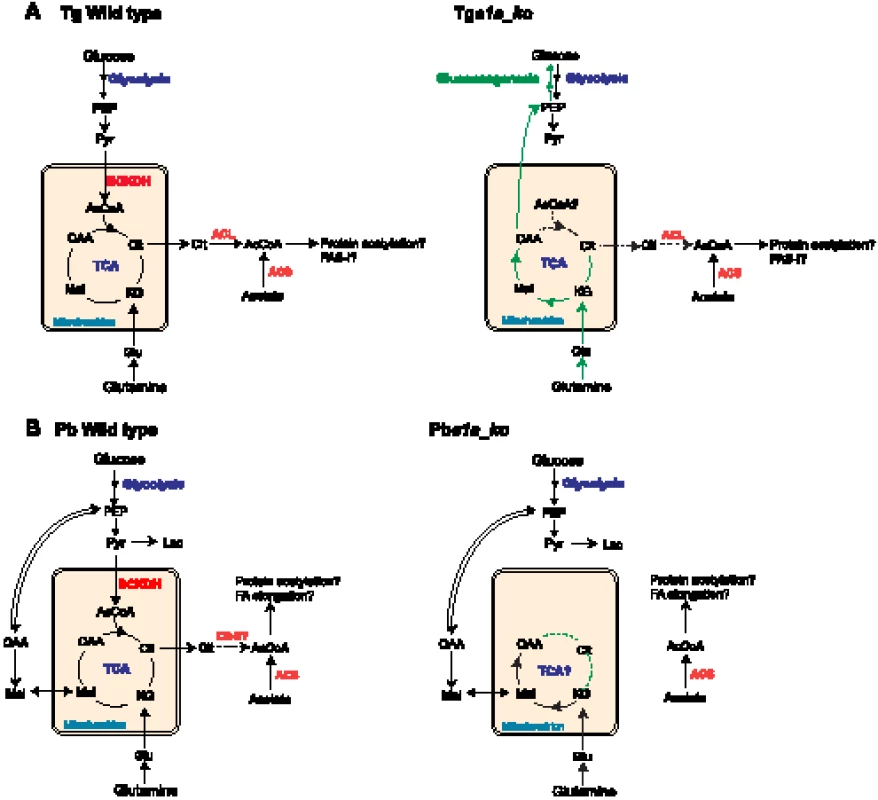

Intriguingly, the disruption of the BCKDH enzyme complex was associated with significant remodelling in the central carbon metabolism in T. gondii (Fig. 8). Metabolic profiling of Tge1a_ko parasites revealed that despite a decrease in citrate, other TCA cycle metabolites including the C4-dicarboxylic acids succinate, fumarate and malate were all unaltered or even increased in abundance, indicating that an alternative carbon source enters the TCA cycle below α-ketoglutarate. T. gondii tachyzoites co-utilize glutamine in the presence of glucose and appear to use this amino acid as an alternative substrate in the absence of glucose [43]. Unexpectedly, we found that carbon skeletons derived from 13C-glutamine were channelled into the gluconeogenic pathway in Tge1a_ko parasites under glucose-replete conditions (Fig. 2C and 8). This metabolic perturbation is not due to interruption of the early steps in the TCA cycle or increased glutaminolysis, since increased gluconeogenic flux is not observed in parasites treated with sodium fluoroacetate, an inhibitor of the TCA cycle enzyme aconitase [20]. Increased gluconeogenesis in Tge1a_ko might result from allosteric activation of key enzymes, as a result of the accumulation of pyruvate or other metabolites. Alternatively, the decreased production of acetyl-CoA in the mutant could lead to global changes in the acetylation state of multiple enzymes in these pathways [44]–[46]. The gluconeogenic enzyme, phosphenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) is activated by deacetylation [47], and this enzyme has been shown to be acetylated in T. gondii tachyzoites, as is cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) [48]. Bacterial acetylated GAPDH has been reported to drive the forward reaction during glycolysis, while it is more active in catalysing the reverse reaction used in gluconeogenesis when deacetylated [45]. A global decrease in protein acetylation as a consequence of blocked acetyl-CoA synthesis could therefore underlie the inappropriate activation of gluconeogenesis in Tge1a_ko (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Proposed metabolic pathways, compartmentalisation and metabolic remodelling in T. gondii and P. berghei.

(A) Schematic representation of the metabolism in T. gondii WT (left panel) and Tge1a_ko (right panel) incorporating data from this study. (B) Scheme of the metabolism in P. berghei WT (left panel) and Pbe1a_ko (right panel). For both (A) and (B), the remodelling of the parasites metabolism upon ablation of BCKDH activity is highlighted in green. Dotted lines represent drops and disruption in the corresponding reactions. Abbreviations: AcCoA, acetyl-CoA; α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; Cit, citrate; Glc, glucose; Glu, glutamate; Gln, glutamine; Lac, lactate; Mal, malate; OAA, oxaloacetic acid; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; Pyr, pyruvate; Suc, succinate. Enzymes in red: BCKDH, branched chain keto acid dehydrogenase; ACL, ATP-citrate lyase; ACS, Acetyl-CoA synthetase; CS-II, second isoform of citrate synthetase. The phenotypic analyses of the BCKDH null mutant revealed an important impact on the physiology of the blood stages of the rodent malaria parasite. In contrast to other P. berghei mutants with defects in central carbon metabolism, such as the mitochondrial complex II (succinate-ubiquinone reductase) [28] and the type II NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (NDH2) [27], the Pbe1a_ko mutant exhibited an obvious phenotypic defect during asexual development in mature red blood cells. Pbe1a_ko parasites readily invaded reticulocytes and normocytes, but failed to develop to schizonts in the latter. While the molecular basis for the selective growth in reticulocytes compared to normocytes is unknown, it is likely that differences in the metabolism of these two host cell types contribute to the observed tropism. In particular, reticulocytes are known to be metabolically more active than normocytes, and may contain essential metabolites that could compensate for the loss of BCKDH function [49], [50]. In support of this conclusion, Pbe1a_ko parasite growth in normocytes was partially restored by supplementation of the medium with acetate (Fig. 6 and 8), indicating that the mutant is able to scavenge acetate or other essential nutrients from reticulocytes in order to survive in the absence of BCKDH. Alternatively, intrinsic - and parasite-induced differences in the permeability of the reticulocyte/normocyte plasma membrane [51]–[53] could lead to a differential accumulation of toxic compounds, such as lactate and pyruvate, and lethality in the Pbe1a_ko strain. These findings also raise the question of the importance of BCKDH for each of the different human malaria parasite species, given that P. falciparum can develop in both immature and mature erythrocytes, whereas P. vivax exhibits a strict preference for reticulocytes [54] and establishes a chronic infection in the liver [55].

We have recently shown that flux of pyruvate derived from glucose into the TCA cycle increases markedly as P. falciparum asexual RBC stages differentiate to gametocyte stages, implying that the steps catalysed by BCKDH may be regulated in a stage-specific manner [21]. Consistent with an increased role for P. falciparum BCKDH in sexual development, the P. berghei BCKDH-E1a mutant exhibited a reduction in both numbers and fitness of gametocytes. Both phenotypes were reversed by complementing the mutant with an orthologous gene from P. falciparum. While a reduction in gametocyte numbers alone would be difficult to interpret given the different infection courses of wild type and mutant parasites, a reduction in the ability of each microgametocyte to release microgametes and of macrogametes to convert to ookinetes is highly significant. Our phenotype is clearly less severe, but otherwise resembles that described by [28] in P. berghei for a mutant in mitochondrial complex II, predicted to have a disrupted TCA cycle downstream of both glucose and glutamine. These data are entirely consistent with a key role for BCKDH in a glucose-fuelled TCA cycle that in P. berghei increases in importance during sexual development.

The P. berghei BCKDH-E1a is essential for transmission through mosquitoes as it is required for sporogony, a period when the young oocysts grow rapidly in size and differentiate into thousands of sporozoites. Oocyst growth was also blocked in an NDH2-deficient P. berghei mutant [27], further highlighting the importance of oxidative phosphorylation during these stages of parasite development. Together, our data suggest that BCKDH plays a key role in the stage-specific changes in flux of glycolytic pyruvate into the TCA cycle in mosquito stages.

This study highlights the metabolic adaptations that have occurred during the evolution of this diverse group of protists and provides new insights into the central carbon metabolism of key pathogenic stages. Since perturbation of mitochondrial metabolism results in significant decrease in parasite fitness in the mammalian host and inhibition of vector transmission, components of the BCKDH complex may be suitable targets for drug development.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were approved and performed in accordance with a project licence issued by the UK Home Office and by the Direction générale de la santé, Domaine de l’expérimentation animale (Avenue de Beau-Séjour 24, 1206 Genève) with the authorization Number (1026/3604/2, GE30/13) according to the guidelines set by the cantonal and international guidelines and regulations issued by the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office.

No human samples were used in these experiments. Human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) were obtained from ATCC.

Antibodies

The antibodies used in this study were described before as follows: mouse monoclonal anti-myc (9E10), polyclonal rabbit anti-GAP45 [56], rabbit anti-PfProfilin [56]. For the production of specific polyclonal antibodies, PfBCKDH-E1a sequence (PF13_0070, aa 277 to 425) was amplified using primers 2391 and 2392 (Table S2) and cloned into pETHb in frame with 6 histidine residues between the NcoI and SalI restriction sites. The corresponding recombinant protein was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 strain and purified by affinity chromatography on Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol under denaturing conditions. Antibodies against PfBCKDH-E1a were raised in rabbits by Eurogentec S.A. (Seraing, Belgium) according to their standard protocol.

Immunofluorescence assay (IFA) and Western blots analysis with these antibodies were performed as previously described [33].

T. gondii strains and culture

T. gondii tachyzoites (RHku80_ko (RH), RHku80_ko/bckdhE1a_ko (Tge1a_ko)) were maintained in HFF using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, GIBCO, Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% foetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine and 25 µg/ml gentamicin at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Generation T. gondii Tge1a_ko

2 kb genomic flanking sequences (FS) of TgBCKDH-E1a (TGME49_239490, www.toxodb.org) ORF were amplified using LATaq polymerase (TaKaRa) and primers 2821 and 2822 for the 5’FS and primers 2823 and 2824 for the 3’FS (Table S2). Amplified regions were then cloned into the KpnI, XhoI sites for the 5’FS and BamHI, NotI sites for the 3’FS of the pTub5HXGPRT vector. T. gondii RHku80_ko tachyzoites were transfected by electroporation as previously described [57] and stable transfectants were selected for by hypoxanthine-xanthine-guanine-phosphoribosyltransferase (HXGPRT) expression in the presence of mycophenolic acid and xanthine as described earlier [58]. Parasites were cloned by limiting dilution in 96 well plates and clones were assessed by genomic PCR and Western blot analysis.

Phenotypic analyses

Plaque assays: HFF monolayers were infected with parasites and let to develop for 7 days before fixation with PFA/GA and Giemsa staining (Sigma-Aldrich GS500) mounted with Fluoromount G and visualized using ZEISS MIRAX imaging system equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 20×/0.8 objective at the bioimaging facility of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva.

Intracellular growth assays: Prior to infection, the HFF monolayers were washed and pre-incubated for 24 h with medium containing the relevant carbon source and kept in this medium for the rest of the experiment. Complete medium is DMEM 41966 (Gibco, Life Technologies) supplemented with 5% FCS, up to 6 mM glutamine, 25 µg/ml gentamicine. Medium depleted in glutamine is DMEM 11960 supplemented with 25 µg/ml gentamicine (Gibco, Life Technologies) and medium depleted in glucose is DMEM 11966 supplemented with up to 6 mM glutamine and 25 µg/ml gentamicine. HFF were inoculated with parasites and coverslips were fixed 24 h post-infection with 4% PFA and stained by IFA with rabbit anti-TgGAP45, mouse anti-myc 9E10. Number of parasites per vacuole was counted in triplicates for each condition (n = 3). More than 200 vacuoles were counted per replicate.

In vivo virulence assay

On day 0, mice were infected by intraperitoneal injection with either wild type RH or Tge1a_ko parasites (∼15 parasites per mouse). 5 female CD1 mice were infected per group. The health of the mice was monitored daily until they presented severe symptoms of acute toxoplasmosis (bristled hair and complete prostration with incapacity to drink or eat) and were sacrificed on that day in accordance to the Swiss regulations of animal welfare. 21 days post-infection, sera from mice that survived primary infection were assessed for seroconversion by Western blot for the presence of anti-T. gondii antibodies. Mice were then challenged with ∼1000 wild-type RH parasites to assess immunization and survival.

Plasmodium berghei culturing

The P. berghei ANKA GFP-con clone 2.3.4 was used to generate transgenic parasites and maintained in female CD1 or Theiler's Original outbred mice as described previously [59]. The course of infection was monitored on Giemsa-stained tail blood smears.

Generation of P. berghei transgenic line

PbBCKDH-E1a sequence was retrieved from the online Plasmodium genome database, (PBANKA_141110, www.plasmodb.org). To generate the PbBCKDH-E1a knockout (Pbe1a_ko), primers 3835 and 2482 were used to amplify a 2 kb region of homology at the 5’end of the PbBCKDH-E1a locus (Table S2). The PCR fragment was cloned between KpnI and ApaI restriction sites of the pBS-DHFR vector containing the T. gondii dhfr conferring pyrimethamine resistance [60]. The 3’ flanking region 2 kb was amplified using primers 3836 and 2483 and cloned between EcoRV and BamHI restriction sites of pBS-DHFR. The final construct was linearized with NotI prior to transfection.

Complementation of Pbe1a_ko by P. falciparum BCKDH-E1a was performed using a knock-in strategy in the promoter region of PbBCKDH-E1a still present in Pbe1a_ko parasites. Primers 4067 and 4068 were used to amplify this promoter region and the PCR (pPbE1a) fragment was cloned between the NotI and ApaI sites of pARL-GFP-Ty-hDHFR. Primers 4070 and 4256 were used to amplify the PfBCKDH-E1a cDNA (PF3D7_1312600, www.plasmodb.org) and cloned between the ApaI and NcoI of the pPbE1a-GFP-Ty-hDHFR. Finally, the 3’UTR of PbBCKDH-E1a was amplified using primers 4257 and 4258 and the PCR fragment cloned between the NcoI and EcoRV sites of pPbE1a-PfE1a-Ty-hDFR in order to generate the final plasmid, pPbE1a-PfE1a-3’PbE1a-hDHFR. This plasmid was linearized by MfeI prior transfection in Pbe1a_ko strain.

Transfections were carried out as previously described [61]. Briefly, after overnight culture of infected red blood cells (37°C, 90 rpm), mature schizont-infected RBC were purified by Nycodenz gradient and collected. 100 µL of Human T Cell Nucleofector Kit (Amaxa) and 15 µg of digested DNA. Electroporation was performed using the U33 program of the Nucleofector electroporator (Amaxa/Lonza). Electroporated parasites were mixed with blood enriched in reticulocytes from phenylhydrazine-treated mice to allow re-invasion and immediately injected (intraperitoneal) into CD1 female mice. Mice were treated with pyrimethamine in drinking water (conc. Final = 0.07 mg/ml), 24 hr after infection. After 3 drug-cycling, infected blood was collected and P. berghei genomic DNA was extracted with SV Wizard Genomic DNA kit (Promega). Pbe1a_ko pools were cloned in RAG-1 -/ - mice by limiting dilution. The integration of the different constructs was confirmed by genomic PCR, using primers listed in table S2 and loss or presence of the protein was validated by Western blot analysis.

Reticulocyte purification and invasion assay of Plasmodium berghei

After separation of the plasma from red blood cells and washes in RPMI by centrifugation (300× g for 10 min), mouse reticulocytes were separated from normocytes by Percoll/NaCl density gradient (1.096–1.058 g/mL) and centrifuged at 250× g for 30 min, as previously described [62], [63]. Reticulocytes were collected from the interface of the two Percoll layers and washed twice with RPMI before culturing. Invasion efficiency in normocytes or purified reticulocytes was assessed by flow cytometry as previously described [64].

Haematocrit

Haematocrit levels were observed in mice over the course of infection with P. berghei wild type and Pbe1a_ko parasites. Briefly, every two days, haematocrit-capillaries (Hirschmann Laborgeräte, 75 mm/18 µL, ammonia heparinized 0,9 IU/capillary) were filled with tail blood and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min to separate the blood layers. Percentage haematocrit was calculated by dividing the packed red blood cell volume length by the total blood volume length (red blood cells and serum).

P. berghei phenotyping through the life cycle

The mice used for the phenotyping were pretreated with 150 µl of 6 mg/ml of phenylhydrazine and infected with 107 parasites two days later. Three days after infection parasitaemia and gametocytaemia were quantified on Giemsa-stained thin blood smears. To quantify exflagellation rates 10 µl blood collected from the tail vain was mixed with 500 µl of ookinete medium (RPMI1640 containing 25 mM HEPES, 20% FCS, 100 µM xanthurenic acid, pH 7.4) and examined using an improved Neubauer hemocytometer 12 min later. The number of erythrocytes and exflagellating microgametocytes were counted and expressed as a percentage of all microgametocytes as independently determined from stained blood films.

To assess ookinete formation 100 µl infected blood were cultured in 10 ml ookinete medium at 19°C for 20 h. Live staining with a Cy3-congugated mouse monoclonal antibody against the P28 protein labeled banana shaped ookinetes and undifferentiated macrogamete derived parasites, whose shape was assessed by microscopy and recorded for at least 100 cells per sample. For transmission studies ∼200 female A. stephensi mosquitos were allowed to feed on the same infected mice. Exflagellation assays, ookinete cultures and mosquito feeds were performed using the same animals (three per strain) on day three of the infection.

Midguts from 20 fed mosquitoes from each cage were dissected in PBS 7 and 14 days after feeding, examined for oocysts, photographed and analysed as described [65]. On day 21 post feeding salivary glands from 20 mosquitoes per group were dissected, homogenized and sporozoites quantified in a hemocytometer. Finally, on day 23 the remaining mosquitoes were allowed to feed on uninfected mice that had been pre-treated with phenylhydrazine two days before. In parallel the salivary glands from 20 mosquitoes were homogenized and injected intravenously into different mice. All animals were observed for 14 days and the time of parasite appearance in the blood was noted.

Metabolite extraction and analysis of T. gondii tachyzoites

Metabolite extraction and analysis of T. gondii tachyzoites was performed as previously described [20]. Intracellular and egressed tachyzoites (2×108 cell equivalents) were extracted in chloroform/methanol/water (1∶3∶1 v/v containing 1 nmol scyllo-inositol or 5 nmol 13C-valine as internal standard for GC-MS and LC-MS, respectively) for 1 h at 4°C, with periodic sonication. For GC-MS analysis polar and apolar metabolites were separated by phase partitioning. Polar metabolite extracts were derivitised by methoximation and trimethylsilylation (TMS) and analysed by GC-MS as previously described [66]. For LC-MS analysis, monophasic metabolite extracts were analysed directly with a ZIC-pHILIC - Orbitrap platform and data analysed with IDEOM as previously described [19], [67]. All metabolites were identified by comparison of retention time and exact mass (LC-MS) or mass spectra (GC-MS) with authentic chemical standards, with the exception of 2-hydroxyethyl-TPP putatively identified by exact mass (<1 ppm) and predicted retention time based on a quantitative structure-retention relationship model for this chromatographic method [68].

Stable isotope labelling of T. gondii tachyzoites, P. berghei-infected and uninfected RBCs

T. gondii: stable isotope labelling, metabolite extraction, and GC-MS analysis was performed for polar metabolites, as previously described [20]. Briefly, infected HFF or freshly egressed tachyzoites were incubated in low-glucose, glutamine-free DMEM, supplemented with either 13C-U-glucose, 13C-U-glutamine, 13C-U-leucine or 13C-U-leucine/13C-U-isoleucine/13C-U-valine (final concentration 8 mM, Spectra Stable Isotopes). Parasites were harvested after 4 h and metabolites extracted as above. Changes in the mass isotopologue abundances of key intermediates in central carbon metabolism were assessed by GC-MS or LC-MS analysis. The level of labelling of individual metabolites was calculated as the percent of the metabolite pool containing one or more 13C atoms after correction for natural abundance and amount of 13C-carbon source compared to 12C-carbon source in the culture medium (as determined by GC-MS analysis). The mass isotopologue distributions (MIDs) of individual metabolites were corrected for the occurrence of natural isotopes in both the metabolite and, in GC-MS experiments, the derivatisation reagent [69]. An untargeted metabolome-wide isotope analysis was performed on high resolution LC-MS data to detect all labelled metabolic products of 13C-U-glucose or 13C-U-leucine/13C-U-isoleucine/13C-U-valine according to the method previously described [70].

P. berghei: stable isotope labelling, metabolite extraction, and GC-MS analysis was adapted from the above protocol. Blood (1 mL) from individual mice infected (iRBC) with WT or Pbe1a_ko parasites (blood at equivalent parasitemia of ∼4%) was collected and all white cells removed by passage of the blood over cellulose CF11 columns. Parasites were cultured for maturation in vitro for 5 h (RPMI1640 containing 25 mM HEPES [Sigma], 0.5% Albumax, 0.2 mM hypoxanthine [pH 7.5], 25 µg/ml Gentamycin), before addition of 8 mM 13C-U-glucose, 13C-U-glutamine, or 13C-U-leucine as required. After 5 h of labelling, cultures were rapidly transferred to a 50 mL centrifuge tube and cellular metabolism quenched as above and schizont-infected RBCs (iRBCs) were purified from uninfected and ring-infected RBCs on Nycodenz gradient, at 4°C. iRBCs and uninfected RBCs (control) were pelleted by centrifugation (800× g, 10 min, 4°C), washed three times with ice-cold PBS, extracted and analysed as above.

In vitro keto-acid dehydrogenase enzyme assay

Cell extracts were prepared from 108 freshly egressed T. gondii tachyzoites by hypotonic lysis with ice-cold lysis buffer (1 mM NaHEPES (pH 7.4, Sigma), 2 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (Sigma), 2 mM dithiothreitol (Biovectra)) for 10 min on ice, in the presence of EDTA-free protease inhibitors (complete, Roche). Extracts were incubated with 0.5 mM or 2 mM of the test keto-acid (4-methyl-2-oxopentanoate, 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate or pyruvate) in the presence of cofactors (5 mM NAD+, 1 mM CoA, 0.1 mM Thiamine-PP, 0.1 mM FAD and 0.05 mM lipoic acid) in 200 µL MgCl2/KH2PO4 (1.3 mM/33 mM) buffer (pH 7) at 37°C for 2 h (n = 2). Samples (20 µL) were extracted in 80 µL methanol/acetonitrile (1∶3) and analysed by LC-MS (pHILIC-QTOF) as described in the metabolomics methods. 3-methylbutanoyl-CoA, 2-methylpropanoyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA were quantified by reference to calibration curves of authentic standards in sample matrix (extracted lysates). Additional TPP intermediates were not quantified due to lack of authentic reference standards, and data are expressed as LC-MS peak areas. The raw high-resolution MS data were interrogated for the occurrence of other possible metabolic products derived from the branched chain keto-acids or acyl-CoAs, and none were detected. Additional controls were analysed to validate the assay including substrate-free and cofactor-free incubations, technical replicates of pooled samples for LC-MS quality control and matrix controls for RH and Tge1a_ko samples (data not shown).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. WeissLM, DubeyJP (2009) Toxoplasmosis: A history of clinical observations. Int J Parasitol 39 : 895–901.

2. DesaiSA, KrogstadDJ, McCleskeyEW (1993) A nutrient-permeable channel on the intraerythrocytic malaria parasite. Nature 362 : 643–646.

3. SchwabJC, BeckersCJ, JoinerKA (1994) The parasitophorous vacuole membrane surrounding intracellular Toxoplasma gondii functions as a molecular sieve. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91 : 509–513.

4. JensenMD, ConleyM, HelstowskiLD (1983) Culture of Plasmodium falciparum: the role of pH, glucose, and lactate. J Parasitol 69 : 1060–1067.

5. RothEJr (1990) Plasmodium falciparum carbohydrate metabolism: a connection between host cell and parasite. Blood Cells 16 : 453–460 discussion 461–456.

6. Al-AnoutiF, TomavoS, ParmleyS, AnanvoranichS (2004) The expression of lactate dehydrogenase is important for the cell cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. J Biol Chem 279 : 52300–52311.

7. van DoorenGG, StimmlerLM, McFaddenGI (2006) Metabolic maps and functions of the Plasmodium mitochondrion. FEMS Microbiol Rev 30 : 596–630.

8. PomelS, LukFC, BeckersCJ (2008) Host cell egress and invasion induce marked relocations of glycolytic enzymes in Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. PLoS Pathog 4: e1000188.

9. ShermanIW (1979) Biochemistry of Plasmodium (malarial parasites). Microbiol Rev 43 : 453–495.

10. BlumeM, HliscsM, Rodriguez-ContrerasD, SanchezM, LandfearS, et al. (2011) A constitutive pan-hexose permease for the Plasmodium life cycle and transgenic models for screening of antimalarial sugar analogs. FASEB J 25 : 1218–1229.

11. SlavicK, StraschilU, ReiningerL, DoerigC, MorinC, et al. (2010) Life cycle studies of the hexose transporter of Plasmodium species and genetic validation of their essentiality. Mol Microbiol 75 : 1402–1413.

12. CrawfordMJ, Thomsen-ZiegerN, RayM, SchachtnerJ, RoosDS, et al. (2006) Toxoplasma gondii scavenges host-derived lipoic acid despite its de novo synthesis in the apicoplast. EMBO J 25 : 3214–3222.

13. FothBJ, StimmlerLM, HandmanE, CrabbBS, HodderAN, et al. (2005) The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum has only one pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, which is located in the apicoplast. Mol Microbiol 55 : 39–53.

14. FleigeT, FischerK, FergusonDJ, GrossU, BohneW (2007) Carbohydrate metabolism in the Toxoplasma gondii apicoplast: localization of three glycolytic isoenzymes, the single pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, and a plastid phosphate translocator. Eukaryot Cell 6 : 984–996.

15. RalphSA (2005) Strange organelles–Plasmodium mitochondria lack a pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Mol Microbiol 55 : 1–4.

16. SeeberF, LimenitakisJ, Soldati-FavreD (2008) Apicomplexan mitochondrial metabolism: a story of gains, losses and retentions. Trends Parasitol 24 : 468–478.

17. DanneJC, GornikSG, MacraeJI, McConvilleMJ, WallerRF (2013) Alveolate mitochondrial metabolic evolution: dinoflagellates force reassessment of the role of parasitism as a driver of change in apicomplexans. Mol Biol Evol 30 : 123–139.

18. PossentiA, FratiniF, FantozziL, PozioE, DubeyJP, et al. (2013) Global proteomic analysis of the oocyst/sporozoite of Toxoplasma gondii reveals commitment to a host-independent lifestyle. BMC Genomics 14 : 183.

19. LimenitakisJ, OppenheimRD, CreekDJ, FothBJ, BarrettMP, et al. (2013) The 2-methylcitrate cycle is implicated in the detoxification of propionate in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Microbiol 87 : 894–908.

20. MacRaeJI, SheinerL, NahidA, TonkinC, StriepenB, et al. (2012) Mitochondrial metabolism of glucose and glutamine is required for intracellular growth of Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Host Microbe 12 : 682–692.

21. MacRaeJI, DixonMW, DearnleyMK, ChuaHH, ChambersJM, et al. (2013) Mitochondrial metabolism of sexual and asexual blood stages of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Biol 11 : 67.

22. CobboldSA, VaughanAM, LewisIA, PainterHJ, CamargoN, et al. (2013) Kinetic flux profiling elucidates two independent acetyl-CoA biosynthetic pathways in Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem 288 : 3638–3650.

23. StormJ, SethiaS, BlackburnGJ, ChokkathukalamA, WatsonDG, et al. (2014) Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxylase Identified as a Key Enzyme in Erythrocytic Plasmodium falciparum Carbon Metabolism. PLoS Pathog 10: e1003876.

24. FoxBA, BzikDJ (2002) De novo pyrimidine biosynthesis is required for virulence of Toxoplasma gondii. Nature 415 : 926–929.

25. HydeJE (2007) Targeting purine and pyrimidine metabolism in human apicomplexan parasites. Curr Drug Targets 8 : 31–47.

26. KeH, MorriseyJM, GanesanSM, PainterHJ, MatherMW, et al. (2011) Variation among Plasmodium falciparum strains in their reliance on mitochondrial electron transport chain function. Eukaryot Cell 10 : 1053–1061.

27. BoysenKE, MatuschewskiK (2011) Arrested oocyst maturation in Plasmodium parasites lacking type II NADH:ubiquinone dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem 286 : 32661–32671.

28. HinoA, HiraiM, TanakaTQ, WatanabeY, MatsuokaH, et al. (2012) Critical roles of the mitochondrial complex II in oocyst formation of rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. J Biochem 152 : 259–268.

29. SrivastavaIK, RottenbergH, VaidyaAB (1997) Atovaquone, a broad spectrum antiparasitic drug, collapses mitochondrial membrane potential in a malarial parasite. J Biol Chem 272 : 3961–3966.

30. DailyJP, ScanfeldD, PochetN, Le RochK, PlouffeD, et al. (2007) Distinct physiological states of Plasmodium falciparum in malaria-infected patients. Nature 450 : 1091–1095.

31. SanaTR, GordonDB, FischerSM, TichySE, KitagawaN, et al. (2013) Global Mass Spectrometry Based Metabolomics Profiling of Erythrocytes Infected with Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS One 8: e60840.

32. AraujoFG, HuskinsonJ, RemingtonJS (1991) Remarkable in vitro and in vivo activities of the hydroxynaphthoquinone 566C80 against tachyzoites and tissue cysts of Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 35 : 293–299.

33. ChanXW, WrengerC, StahlK, BergmannB, WinterbergM, et al. (2013) Chemical and genetic validation of thiamine utilization as an antimalarial drug target. Nat Commun 4 : 2060.

34. ÆvarssonA, ChuangJL, WynnRM, TurleyS, ChuangDT, et al. (2000) Crystal structure of human branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase and the molecular basis of multienzyme complex deficiency in maple syrup urine disease. Structure 8 : 277–291.

35. HuynhMH, CarruthersVB (2009) Tagging of endogenous genes in a Toxoplasma gondii strain lacking Ku80. Eukaryot Cell 8 : 530–539.

36. FoxBA, RistucciaJG, GigleyJP, BzikDJ (2009) Efficient gene replacements in Toxoplasma gondii strains deficient for nonhomologous end joining. Eukaryot Cell 8 : 520–529.

37. MombaertsP, IacominiJ, JohnsonRS, HerrupK, TonegawaS, et al. (1992) RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell 68 : 869–877.

38. PainterHJ, MorriseyJM, MatherMW, VaidyaAB (2007) Specific role of mitochondrial electron transport in blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 446 : 88–91.

39. BunikVI, DegtyarevD (2008) Structure-function relationships in the 2-oxo acid dehydrogenase family: substrate-specific signatures and functional predictions for the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase-like proteins. Proteins 71 : 874–890.

40. AndrewsFH, McLeishMJ (2012) Substrate specificity in thiamin diphosphate-dependent decarboxylases. Bioorg Chem 43 : 26–36.

41. BrickerDK, TaylorEB, SchellJC, OrsakT, BoutronA, et al. (2012) A mitochondrial pyruvate carrier required for pyruvate uptake in yeast, Drosophila, and humans. Science 337 : 96–100.

42. HerzigS, RaemyE, MontessuitS, VeutheyJL, ZamboniN, et al. (2012) Identification and functional expression of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Science 337 : 93–96.

43. BlumeM, Rodriguez-ContrerasD, LandfearS, FleigeT, Soldati-FavreD, et al. (2009) Host-derived glucose and its transporter in the obligate intracellular pathogen Toxoplasma gondii are dispensable by glutaminolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 12998–13003.

44. WellenKE, HatzivassiliouG, SachdevaUM, BuiTV, CrossJR, et al. (2009) ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science 324 : 1076–1080.

45. WangQ, ZhangY, YangC, XiongH, LinY, et al. (2010) Acetylation of metabolic enzymes coordinates carbon source utilization and metabolic flux. Science 327 : 1004–1007.

46. ZhaoS, XuW, JiangW, YuW, LinY, et al. (2010) Regulation of cellular metabolism by protein lysine acetylation. Science 327 : 1000–1004.

47. JiangW, WangS, XiaoM, LinY, ZhouL, et al. (2011) Acetylation regulates gluconeogenesis by promoting PEPCK1 degradation via recruiting the UBR5 ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell 43 : 33–44.

48. JeffersV, SullivanWJJr (2012) Lysine acetylation is widespread on proteins of diverse function and localization in the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Eukaryot Cell 11 : 735–742.

49. YamasakiM, OtsukaY, YamatoO, TajimaM, MaedeY (2000) The cause of the predilection of Babesia gibsoni for reticulocytes. J Vet Med Sci 62 : 737–741.