-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Generators of Phenotypic Diversity in the Evolution of Pathogenic Microorganisms

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 9(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003181

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003181Summary

article has not abstract

Introduction

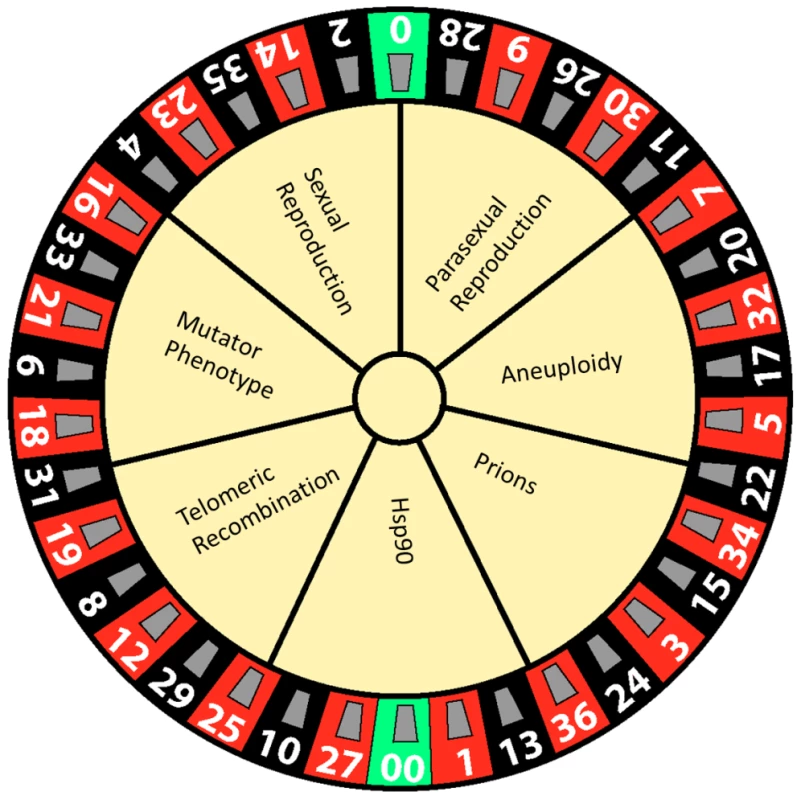

All organisms run the gauntlet of Darwinian selection. Poignant examples include microbial pathogens, which must survive and thrive in their hosts. The process of pathogen adaptation to the host is diverse and is now known to involve a panoply of diversity generators, such as sexual/parasexual reproduction, aneuploidy, prions, mutators, telomeric silencing/recombination, and Hsp90 as a capacitor for evolution [1], [2] (Figure 1). Given the vast diversity of known mechanisms that can generate phenotypic and genotypic assortments, others likely remain to be discovered.

Fig. 1. Generators of phenotypic diversity illustrated as a game of chance.

Evolution is a multifactorial process that depends on numerous complex factors, including routes to diversity that can be deleterious, neutral, or advantageous depending on the environment. Here we depict these evolutionary trajectories using the analogy of a roulette wheel in which one possible path yields a winner that develops a new trait that allows the microorganism to survive in novel conditions, such as a host treated with antimicrobial agents. However, as in roulette, the odds are against the gambler and the other routes and outcomes are deleterious. Sexual and Parasexual Reproduction Create Diversity

Most eukaryotic microorganisms are either known or suspected to undergo sexual reproduction. However, as recently as two decades ago, most pathogenic eukaryotic microbes, including fungi and parasites, were thought to be clonal and asexual [3], [4]. Over the past decade, we have witnessed a renaissance in this field and now appreciate that most, and perhaps all, pathogenic fungi and parasites have retained sexual capacity [5], [6]. In many cases, their sexual cycles can be difficult to observe, due to being cryptic or having a unisexual or even parasexual cycle. These modes of reproduction share the ability to promote some level of genetic exchange, but involve inbreeding or even selfing in many instances, helping to preserve well-adapted genomic configurations while simultaneously generating limited genetic diversity that may promote adaptation to less rapidly changing host or environmental niches.

Pathogenic microbes can reproduce parasexually or sexually. Parasexuality involves cell–cell fusion and ploidy reduction through stochastic, random chromosome loss. This phenomenon was originally described by Pontecorvo for Aspergillus nidulans [7], and has been more recently described in Candida albicans by Forche and colleagues [8]. Parasex can produce genetic diversity via independent chromosomal assortment, mitotic recombination, and the ability of the diploid state to act as a capacitor for evolution by enabling the accumulation of recessive mutations that are deleterious individually but beneficial in combination (so-called reciprocal sign epistasis) [9].

Sexual reproduction can accelerate evolution by purging the genome of deleterious mutations or by bringing together combinations of advantageous alleles. Opposite-sex mating promotes genetic exchange via outcrossing, whereas unisexual reproduction can involve inbreeding or selfing to yield more limited genetic exchange. The capacity to engage in opposite sexual, unisexual, and asexual reproduction may be a bet-hedging strategy that enables microbes to better adapt to a range of environments, including the host. The fact that two of the most common human fungal pathogens, C. albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans, have retained the capacity for a sexual cycle involving opposite-sex mating as well as the capability of unisexual reproduction, provides an illustration of convergent evolution [10], [11]. Recent discoveries on the sexual nature of parasitic pathogens, including examples of unisexuality and selfing [12], [13], unify this paradigm across the two major groups of eukaryotic pathogens.

Aneuploidy: Deleterious or Advantageous?

Aneuploidy can be deleterious, which is exemplified in common human genetic diseases, such as Down's syndrome, and in cancers. However, aneuploidy also can be advantageous. In fungi, aneuploidy confers antifungal drug resistance and enables rapid adaptive evolution. In addition, these findings may extend to protozoan parasites.

In C. albicans, the most common human fungal pathogen, treating patients with fluconazole results in the rapid emergence of drug-resistant aneuploid isolates [14]. These azole-resistant isolates harbor a novel isochromosome containing two left arms of chromosome 5. Notably, this amplified genomic region includes two key genes: ERG11, which encodes lanosterol 14 alpha demethylase, the target of azole antifungal drugs, and TAC1, which encodes a transcription factor that activates drug efflux pump expression. Strikingly, a similar type of aneuploidy underlies azole resistance in C. neoformans, the second most common human systemic fungal pathogen [15]. In this example, disomy of chromosome 1 is responsible for azole heteroresistance and remarkably contains two key target genes: one encodes Erg11 and the second encodes Afr1, a major efflux pump for azoles. Recent studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae further underscore a central role for aneuploidy in enabling rapid adaptive evolution and also reveal novel phenotypes associated with aneuploidy [16], [17]. Additionally, mutations have been identified that allow strains to better tolerate aneuploidy by enabling the turnover of otherwise deleterious proteins in stoichiometric imbalance [18].

The impact of aneuploidy extends beyond model and pathogenic fungi to parasitic pathogens. Recent studies reveal that populations of the protozoan parasite Leishmania are ensembles of different ploidy states, including individuals that are monosomic, disomic, or trisomic for different chromosomes [19], [20]. The resulting state has been termed mosaic aneuploidy [21] and may contribute to drug resistance and promote pathogenesis, analogous to fungal azole resistance, by enabling genotypic and thereby phenotypic diversification.

Hsp90 as a Capacitor for Evolution

The Hsp90 chaperone system alters relationships between genotypes and phenotypes under conditions of environmental stress, and thereby plays a role in evolutionary processes and provides a route to genetically complex traits in a single mechanistic step [22].

Populations contain silent genetic variation, which can be buffered by chaperones such as the heat-shock protein Hsp90. Hsp90 interacts with, and maintains in their active state, a diverse set of “client” proteins, many of which are signal-transducing kinases or transcription factors involved in cell cycle and developmental regulation. Minor changes in amino acid sequence could have important effects on conformational stability or function of these regulatory proteins as well as a wide range of other proteins. Hsp90 recognizes characteristic structures rather than specific sequences, and is therefore able to chaperone these unstable proteins. In this way, Hsp90 buffers genotypic variation, allowing diversity to accumulate in a latent form under neutral conditions. General protein damage, or moderate changes in growth conditions such as heat stress, diverts Hsp90 from its usual targets to different, partially denatured proteins, uncovering morphological variants that are then expressed under these conditions. Eventually, these variants can become fixed genetic traits independent of chaperone regulation or loss. This surprising role for Hsp90 as a capacitor for morphological evolution and phenotypic variation is conserved across the fungal, plant, and animal kingdoms [1], [2], [23]. Hsp90 can also act as a potentiator of variability by: 1) chaperoning mutated cell regulators that are prone to misfolding, or 2) through its interaction with the cell signaling regulator calcineurin, allowing new traits such as drug resistance to appear in a diverse range of fungal species [23].

Prions Can Drive Evolution

Prions were originally discovered via their ability to cause disease in mammals, including spongiform encephalopathies such as Kuru and fatal familial insomnia, and were found to be unusual, infectious, or inheritable variant forms of a host protein. Prions are also known to occur in fungal species where they can also be deleterious [24], [25]. However, prions can provide mechanisms to unveil preexisting variation. One such protein that can become a prion, Sup35, is an S. cerevisiae translation termination factor. Like other prion-forming proteins, Sup35 contains an N-terminal domain that is dispensable for the normal function of the protein and can occasionally adopt an amyloid conformation, converting the protein to its prion state [PSI+]. When this occurs, Sup35 forms inactive complexes sequestering most of the protein and increasing the frequency of stop codon readthrough to result in proteins with novel C-terminal extensions. The ability to switch to the [PSI+] state can thereby provide a temporary survival advantage under diverse conditions by exposing previously concealed genetic variation. This was observed when cells from different genetic backgrounds were grown as the [PSI+] or [psi−] state in more than 150 phenotypic assays, including inhibitors of diverse cellular processes, general stress conditions, and different temperatures [26], [27]. The advantageous switch to the [PSI+] state expands the population size of organisms with this phenotypic state, increasing the likelihood that this new trait may be fixed in the population as a result of subsequent genetic change [28]. By connecting protein homeostasis with stress responses, prions can drive phenotypic plasticity and thereby allow cells to grow under new conditions without necessarily preventing them from surviving in their former environment [29].

Recombinant Telomeres Cloak Microbial Pathogens

Telomeric and subtelomeric regions are locations whose genomic content can be rapidly restructured. Trypanosomes (unicellular, parasitic, and flagellated protozoa) capitalize on this capacity as part of their pathogenic strategy. The trypanosome cell surface is highly immunogenic, but rapid switching to different surface glycoproteins enables immune evasion. The trypanosome genome encodes more than 1,000 different surface glycoproteins, but only one is expressed at any given time by virtue of its location at one of approximately 15 different subtelomeric expression sites. Two of the three predominant mechanisms for switching result from recombination between telomeres, either through homologous recombination or gene conversion [30]. Similarly, in the pathogenic fungus Candida glabrata, a large family of EPA adhesin genes are clustered in subtelomeric genomic regions, and most of these genes are silenced by a SIR3-dependent telomeric silencing pathway. While the loss of any individual member of the EPA family confers little phenotypic change, loss of an entire cluster decreases pathogenicity, suggesting redundancy between different family members [31].

In other pathogens, such the plant pathogenic fungus Magnaporthe grisea, virulence determinants are also clustered in subtelomeric regions. Approximately 50% of identified M. grisea avirulence genes are located in subtelomeres [32]. Avirulence genes typically mediate host invasion, but are individually recognized by hosts with the correct immune receptors. Loss or inactivation of an avirulence gene can therefore increase pathogenicity under some circumstances, while retention is favored in other situations. The telomeres of rye grass–infecting strains of M. grisea are unstable during growth, which may serve as a mechanism to silence or delete avirulence genes [33].

Mutator States Diversify Genomic Repertoire

Diversity can also be generated through the development of a “mutator” state in which the frequency of mutations is dramatically increased. Inactivation of mismatch repair or loss of oxidative stress protection enzymes can create heritable mutator phenotypes by destabilizing the genome. Alternatively, transient mutator states are also possible. Two examples include the induction of the SOS response in Escherichia coli and the stochastic mistranslation of DNA polymerase in a single cell, resulting in errors in DNA replication [34], [35]. While the mutations created by a transient mutator are heritable, the hypermutability state itself is not.

Typically hypermutability would be seen as evolutionarily disfavored, but in the short term, it can enable adaptation to a new, previously inhospitable environment. For example, the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients are often infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Progression of cystic fibrosis injures the lungs, which results in a constantly changing environment for the pathogen. A substantial proportion of chronic P. aeruginosa infections are caused by mutator strains, while acute infections are not, suggesting that mutability potentiates long-term adaptation [36]. In fungi, loss of mismatch repair genes like MSH2 can result in destabilization of repeat tracts [37]. This enables alteration of adhesin genes in S. cerevisiae, many of which contain repeat tracts [38]. Intragenic repeats are also present in the cell surface genes of a number of other pathogens, including Aspergillus fumigatus, C. albicans, and Plasmodium [39]. The majority of hypermutator studies have been conducted in bacteria, and further study in pathogenic fungi and parasites is an area ripe for exploration, as illustrated by a recent study implicating mutator action in C. neoformans colony/cell morphology variation selected by growth with amoeba [40].

Many of the pathways that cause advantageous mutator phenotypes in bacteria or yeasts are implicated in oncogenesis in mammals. Destabilization of repeat tracts in yeast can be adaptive, but loss of the MSH2 homolog in humans results in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer [41], [42]. Likewise, transient mutators are thought to be responsible for some of the multiple hit mutations required for carcinogenesis [43].

Microorganisms are able to evolve via all of the resources they have available, even when many routes seem detrimental at first glance. Here we have endeavored to summarize recent advances to provide a broad vision of this topic. Other examples have not been covered because of space limitations, such as genetic noise or transposon movement, and probably even more will be discovered in the future, since we know from Lewis Carroll that “it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”

Zdroje

1. RutherfordSL, LindquistS (1998) Hsp90 as a capacitor for morphological evolution. Nature 396 : 336–342.

2. QueitschC, SangsterTA, LindquistS (2002) Hsp90 as a capacitor of phenotypic variation. Nature 417 : 618–624.

3. TibayrencM, KjellbergF, ArnaudJ, OuryB, BrenièreSF, et al. (1991) Are eukaryotic microorganisms clonal or sexual? A population genetics vantage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88 : 5129–5133.

4. TibayrencM, KjellbergF, AyalaFJ (1990) A clonal theory of parasitic protozoa: the population structures of Entamoeba, Giardia, Leishmania, Naegleria, Plasmodium, Trichomonas, and Trypanosoma and their medical and taxonomical consequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87 : 2414–2418.

5. HeitmanJ (2006) Sexual reproduction and the evolution of microbial pathogens. Curr Biol 16: R711–725.

6. HeitmanJ (2010) Evolution of eukaryotic microbial pathogens via covert sexual reproduction. Cell Host Microbe 8 : 86–99.

7. PontecorvoG (1956) The parasexual cycle in fungi. Annu Rev Microbiol 10 : 393–400.

8. ForcheA, AlbyK, SchaeferD, JohnsonAD, BermanJ, et al. (2008) The parasexual cycle in Candida albicans provides an alternative pathway to meiosis for the formation of recombinant strains. PLoS Biol 6: e110 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060110

9. SchoustraSE, DebetsAJM, SlakhorstM, HoekstraRF (2007) Mitotic recombination accelerates adaptation in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS Genet 3: e68 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030068

10. LinX, HullCM, HeitmanJ (2005) Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nature 434 : 1017–1021.

11. AlbyK, SchaeferD, BennettRJ (2009) Homothallic and heterothallic mating in the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. Nature 460 : 890–893.

12. PoxleitnerMK, CarpenterML, MancusoJJ, WangCJ, DawsonSC, et al. (2008) Evidence for karyogamy and exchange of genetic material in the binucleate intestinal parasite Giardia intestinalis. Science 319 : 1530–1533.

13. WendteJM, MillerMA, LambournDM, MagargalSL, JessupDA, et al. (2010) Self-mating in the definitive host potentiates clonal outbreaks of the apicomplexan parasites Sarcocystis neurona and Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Genet 6: e1001261 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001261

14. SelmeckiA, ForcheA, BermanJ (2006) Aneuploidy and isochromosome formation in drug-resistant Candida albicans. Science 313 : 367–370.

15. SionovE, LeeH, ChangYC, Kwon-ChungKJ (2010) Cryptococcus neoformans overcomes stress of azole drugs by formation of disomy in specific multiple chromosomes. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000848 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000848

16. RancatiG, PavelkaN, FlehartyB, NollA, TrimbleR, et al. (2008) Aneuploidy underlies rapid adaptive evolution of yeast cells deprived of a conserved cytokinesis motor. Cell 5 : 879–893.

17. TorresEM, SokolskyT, TuckerCM, ChanLY, BoselliM, et al. (2007) Effects of aneuploidy on cellular physiology and cell division in haploid yeast. Science 317 : 916–924.

18. TorresEM, DephoureN, PanneerselvamA, TuckerCM, WhittakerCA, et al. (2010) Identification of aneuploidy-tolerating mutations. Cell 143 : 71–83.

19. MannaertA, DowningT, ImamuraH, DujardinJC (2012) Adaptive mechanisms in pathogens: universal aneuploidy in Leishmania. Trends Parasitol 28 : 370–376.

20. UbedaJM, LégaréD, RaymondF, OuameurAA, BoisvertS, et al. (2008) Modulation of gene expression in drug resistant Leishmania is associated with gene amplification, gene deletion and chromosome aneuploidy. Genome Biol 9: R115.

21. SterkersY, LachaudL, BourgeoisN, CrobuL, BastienP, et al. (2012) Novel insights into genome plasticity in eukaryotes: mosaic aneuploidy in Leishmania. Mol Microbiol 86 : 15–23.

22. JaroszDF, LindquistS (2010) Hsp90 and environmental stress transform the adaptive value of natural genetic variation. Science 330 : 1820–1824.

23. CowenLE, LindquistS (2005) Hsp90 potentiates the rapid evolution of new traits: drug resistance in diverse fungi. Science 309 : 2185–2189.

24. WicknerRB (1994) [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: evidence for a prion analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 264 : 566–569.

25. KellyAC, ShewmakerFP, KryndushkinD, WicknerRB (2012) Sex, prions, and plasmids in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: E2683–2690.

26. TrueHL, LindquistS (2000) A yeast prion provides a mechanism for genetic variation and phenotypic diversity. Nature 407 : 477–483.

27. TrueHL, BerlinI, LindquistSL (2004) Epigenetic regulation of translation reveals hidden genetic variation to produce complex traits. Nature 431 : 184–187.

28. HalfmannR, LindquistS (2010) Epigenetics in the extreme: prions and the inheritance of environmentally acquired traits. Science 330 : 629–632.

29. HalfmannR, JaroszDF, JonesSK, ChangA, LancasterAK, et al. (2012) Prions are a common mechanism for phenotypic inheritance in wild yeasts. Nature 482 : 363–368.

30. Hovel-MinerGA, BoothroydCE, MugnierM, DreesenO, CrossGAM, et al. (2012) Telomere length affects the frequency and mechanism of antigenic variation in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002900 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002900

31. De Las PeñasA, PanS-J, CastañoI, AlderJ, CreggR, et al. (2003) Virulence-related surface glycoproteins in the yeast pathogen Candida glabrata are encoded in subtelomeric clusters and subject to RAP1 - and SIR-dependent transcriptional silencing. Genes Dev17 : 2245–2258.

32. FarmanML (2007) Telomeres in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae: the world of the end as we know it. FEMS Microbiol Lett 273 : 125–132.

33. StarnesJH, ThornburyDW, NovikovaOS, RehmeyerCJ, FarmanML (2012) Telomere-targeted retrotransposons in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae: agents of telomere instability. Genetics 191 : 389–406.

34. FijalkowskaIJ, DunnRL, SchaaperRM (1997) Genetic requirements and mutational specificity of the Escherichia coli SOS mutator activity. J Bacteriol 179 : 7435–7445.

35. NinioJ (1991) Transient mutators: a semiquantitative analysis of the influence of translation and transcription errors on mutation rates. Genetics 129 : 957–962.

36. OliverA, CantonR, CampoP, BaqueroF, BlazquezJ (2000) High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science 288 : 1251–1253.

37. StrandM, ProllaTA, LiskayRM, PetesTD (1993) Destabilization of tracts of simple repetitive DNA in yeast by mutations affecting DNA mismatch repair. Nature 365 : 274–276.

38. VerstrepenKJ, JansenA, LewitterF, FinkGR (2005) Intragenic tandem repeats generate functional variability. Nat Genet 37 : 986–990.

39. LevdanskyE, RomanoJ, ShadkchanY, SharonH, VerstrepenKJ, et al. (2007) Coding tandem repeats generate diversity in Aspergillus fumigatus genes. Eukaryot Cell 6 : 1380–1391.

40. MagditchDA, LiuT-B, XueC, IdnurmA (2012) DNA mutations mediate microevolution between host-adapted forms of the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002936 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002936

41. FishelR, LescoeMK, RaoMR, CopelandNG, JenkinsNA, et al. (1993) The human mutator gene homolog MSH2 and its association with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Cell 75 : 1027–1038.

42. ParsonsR, LiGM, LongleyMJ, FangWH, PapadopoulosN, et al. (1993) Hypermutability and mismatch repair deficiency in RER+ tumor cells. Cell 75 : 1227–1236.

43. DrakeJW, BebenekA, KisslingGE, PeddadaS (2005) Clusters of mutations from transient hypermutability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 12849–12854.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 3- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Choroby jater v ordinaci praktického lékaře – význam jaterních testů

- Diagnostický algoritmus při podezření na syndrom periodické horečky

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Surviving the Heat of the Moment: A Fungal Pathogens Perspective

- Redefining the Immune System as a Social Interface for Cooperative Processes

- Post-Treatment HIV-1 Controllers with a Long-Term Virological Remission after the Interruption of Early Initiated Antiretroviral Therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study

- Rational Engineering of Recombinant Picornavirus Capsids to Produce Safe, Protective Vaccine Antigen

- Influenza Virus Aerosols in Human Exhaled Breath: Particle Size, Culturability, and Effect of Surgical Masks

- Glycomic Analysis of Human Respiratory Tract Tissues and Correlation with Influenza Virus Infection

- Evolution of Virulence in Emerging Epidemics

- Monomeric Nucleoprotein of Influenza A Virus

- The Enterovirus 71 A-particle Forms a Gateway to Allow Genome Release: A CryoEM Study of Picornavirus Uncoating

- HIV Restriction by APOBEC3 in Humanized Mice

- Transcriptional Responses of Praziquantel Exposure in Schistosomes Identifies a Functional Role for Calcium Signalling Pathway Member CamKII

- Genome-wide Determinants of Proviral Targeting, Clonal Abundance and Expression in Natural HTLV-1 Infection

- TIM-3 Does Not Act as a Receptor for Galectin-9

- Chronic Wasting Disease in Bank Voles: Characterisation of the Shortest Incubation Time Model for Prion Diseases

- Escapes Fumagillin Control in Honey Bees

- Generators of Phenotypic Diversity in the Evolution of Pathogenic Microorganisms

- Plasminogen Controls Inflammation and Pathogenesis of Influenza Virus Infections via Fibrinolysis

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Escapes Fumagillin Control in Honey Bees

- TIM-3 Does Not Act as a Receptor for Galectin-9

- HIV Restriction by APOBEC3 in Humanized Mice

- Influenza Virus Aerosols in Human Exhaled Breath: Particle Size, Culturability, and Effect of Surgical Masks

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání