-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaSocial Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review

Background:

The quality and quantity of individuals' social relationships has been linked not only to mental health but also to both morbidity and mortality.Objectives:

This meta-analytic review was conducted to determine the extent to which social relationships influence risk for mortality, which aspects of social relationships are most highly predictive, and which factors may moderate the risk.Data Extraction:

Data were extracted on several participant characteristics, including cause of mortality, initial health status, and pre-existing health conditions, as well as on study characteristics, including length of follow-up and type of assessment of social relationships.Results:

Across 148 studies (308,849 participants), the random effects weighted average effect size was OR = 1.50 (95% CI 1.42 to 1.59), indicating a 50% increased likelihood of survival for participants with stronger social relationships. This finding remained consistent across age, sex, initial health status, cause of death, and follow-up period. Significant differences were found across the type of social measurement evaluated (p<0.001); the association was strongest for complex measures of social integration (OR = 1.91; 95% CI 1.63 to 2.23) and lowest for binary indicators of residential status (living alone versus with others) (OR = 1.19; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.44).Conclusions:

The influence of social relationships on risk for mortality is comparable with well-established risk factors for mortality.

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 7(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316Summary

Background:

The quality and quantity of individuals' social relationships has been linked not only to mental health but also to both morbidity and mortality.Objectives:

This meta-analytic review was conducted to determine the extent to which social relationships influence risk for mortality, which aspects of social relationships are most highly predictive, and which factors may moderate the risk.Data Extraction:

Data were extracted on several participant characteristics, including cause of mortality, initial health status, and pre-existing health conditions, as well as on study characteristics, including length of follow-up and type of assessment of social relationships.Results:

Across 148 studies (308,849 participants), the random effects weighted average effect size was OR = 1.50 (95% CI 1.42 to 1.59), indicating a 50% increased likelihood of survival for participants with stronger social relationships. This finding remained consistent across age, sex, initial health status, cause of death, and follow-up period. Significant differences were found across the type of social measurement evaluated (p<0.001); the association was strongest for complex measures of social integration (OR = 1.91; 95% CI 1.63 to 2.23) and lowest for binary indicators of residential status (living alone versus with others) (OR = 1.19; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.44).Conclusions:

The influence of social relationships on risk for mortality is comparable with well-established risk factors for mortality.

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' SummaryIntroduction

“Social relationships, or the relative lack thereof, constitute a major risk factor for health—rivaling the effect of well established health risk factors such as cigarette smoking, blood pressure, blood lipids, obesity and physical activity”

—House, Landis, and Umberson; Science 1988 [1]

Two decades ago a causal association between social relationships and mortality was proposed after a review of five large prospective studies concluded that social relationships predict mortality [1]. Following the publication of this provocative review, the number of prospective studies of mortality that included measures of social relationships increased exponentially. Although the inverse association between social relationships and nonsuicide mortality has received increased attention in research, neither major health organizations nor the general public recognize it as a risk factor for mortality. This may be due in part to the fact that the literature has become unwieldy, with wide variation in how social relationships are measured across a large number of studies and disappointing clinical trials [2]. “Social relationships” has perhaps become viewed as a fuzzy variable, lacking the level of precision and control that is preferred in biomedical research. Thus, the large corpus of relevant empirical research is in need of synthesis and refinement.

Current evidence also indicates that the quantity and/or quality of social relationships in industrialized societies are decreasing. For instance, trends reveal reduced intergenerational living, greater social mobility, delayed marriage, dual-career families, increased single-residence households, and increased age-related disabilities [3],[4]. More specifically, over the last two decades there has been a three-fold increase in the number of Americans who report having no confidant—now the modal response [3]. Such findings suggest that despite increases in technology and globalization that would presumably foster social connections, people are becoming increasingly more socially isolated. Given these trends, understanding the nature and extent of the association between social relationships and mortality is of increased temporal importance.

There are two general theoretical models that propose processes through which social relationships may influence health: the stress buffering and main effects models [5]. The buffering hypothesis suggests that social relationships may provide resources (informational, emotional, or tangible) that promote adaptive behavioral or neuroendocrine responses to acute or chronic stressors (e.g., illness, life events, life transitions). The aid from social relationships thereby moderates or buffers the deleterious influence of stressors on health. From this perspective, the term social support is used to refer to the real or perceived availability of social resources [6]. The main effects model proposes that social relationships may be associated with protective health effects through more direct means, such as cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and biological influences that are not explicitly intended as help or support. For instance, social relationships may directly encourage or indirectly model healthy behaviors; thus, being part of a social network is typically associated with conformity to social norms relevant to health and self-care. In addition, being part of a social network gives individuals meaningful roles that provide self-esteem and purpose to life [7],[8].

Social relationships have been defined and measured in diverse ways across studies. Despite striking differences, three major components of social relationships are consistently evaluated [5]: (a) the degree of integration in social networks [9], (b) the social interactions that are intended to be supportive (i.e., received social support), and (c) the beliefs and perceptions of support availability held by the individual (i.e., perceived social support). The first subconstruct represents the structural aspects of social relationships and the latter two represent the functional aspects. Notably, these different subconstructs are only moderately intercorrelated, typically ranging between r = 0.20 and 0.30 [9],[10]. While all three components have been shown to be associated with morbidity and mortality, it is thought that each may influence health in different ways [11],[12]. Because it is presently unclear whether any single aspect of social relationships is more predictive than others, synthesis of data across studies using several types of measures of social relationships would allow for essential comparisons that have not been conducted on such a large scale.

Empirical data suggest the medical relevance of social relationships in improving patient care [13], increasing compliance with medical regimens [13], and promoting decreased length of hospitalization [14],[15]. Likewise, social relationships have been linked to the development [16],[17] and progression [18]–[21] of cardiovascular disease [22]—a leading cause of death globally. Therefore, synthesis of the current empirical evidence linking social relationships and mortality, along with clarifications of potential moderators, may be particularly relevant to public health and clinical practice for informing interventions and policies aimed at reducing risk for mortality.

To address these issues, we conducted a meta-analysis of the literature investigating the association between social relationships and mortality. Specifically, we addressed the following questions: What is the overall magnitude of the association between social relationships and mortality across research studies? Do structural versus functional aspects of social relationships differentially impact the risk for mortality? Is the association moderated by participant characteristics (age, gender, health status, cause of mortality) or by study characteristics (length of clinical follow-up, inclusion of statistical controls)? Is the influence of social relationships on mortality a gradient or threshold effect?

Methods

Identification of Studies

To identify published and unpublished studies of the association between social relationships and mortality, we used three techniques. First, we conducted searches of studies from January 1900 to January 2007 using several electronic databases: Dissertation Abstracts, HealthSTAR, Medline, Mental Health Abstracts, PsycINFO, Social Sciences Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts via SocioFile, Academic Search Premier, ERIC, and Family & Society Studies Worldwide. To capture the broadest possible sample of relevant articles, we used multiple search terms, including mortality, death, decease(d), died, dead, and remain(ed) alive, which were crossed with search words related to social relationships, including the terms social and interpersonal linked to the following words: support, network, integration, participation, cohesion, relationship, capital, and isolation To reduce inadvertent omissions, we searched databases yielding the most citations (Medline, PsycINFO) two additional times. Next, we manually examined the reference sections of past reviews and of studies meeting the inclusion criteria to locate articles not identified in the database searches. Finally, we sent solicitation letters to authors who had published three or more articles on the topic.

Inclusion Criteria

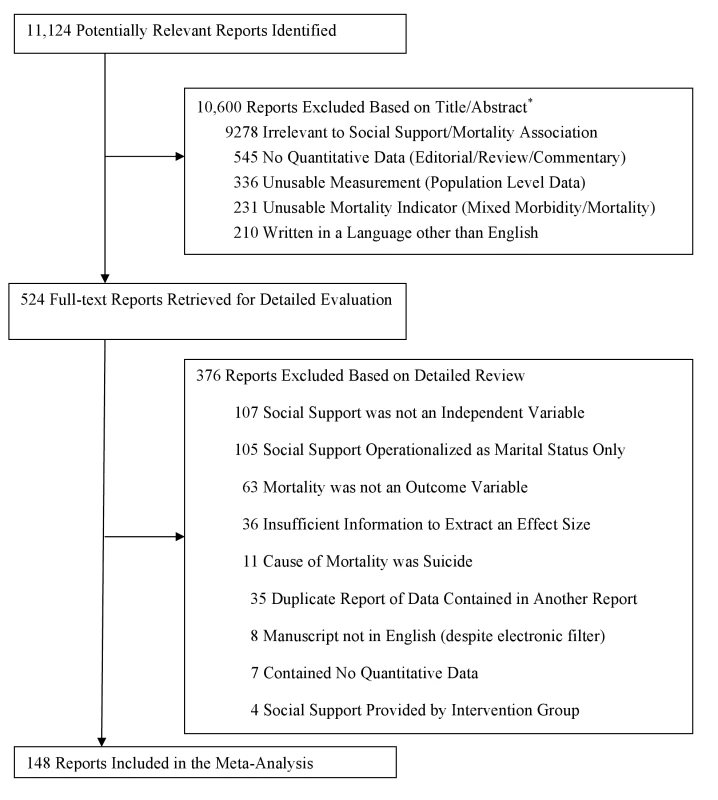

We included in the meta-analysis studies that provided quantitative data regarding individuals' mortality as a function of social relationships, including both structural and functional aspects [23]. Because we were interested in the impact of social relationships on disease, we excluded studies in which mortality was a result of suicide or injury. We also excluded studies in which the only measurement of social support was an intervention provided within the context of the study (e.g., support group), the source of social support was nonhuman (e.g., a pet or higher power), or the social support was provided to others (i.e., giving support to others or measures of others' benefit from the support provided) rather than to the individual tracked for mortality status. We coded studies that included participant marital status as one of several indicators of social support, but we excluded studies in which marital status was the only indicator of social support. We also excluded studies in which the outcome was not explicitly and solely mortality (e.g., combined outcomes of morbidity/mortality). Reports with exclusively aggregated data (e.g., census-level statistics) were also excluded. Manuscripts coded were all written in English, which accounted for 98% of the total retrieved. See Figure 1 for additional details.

Data Abstraction

To increase the accuracy of coding and data entry, each article was initially coded by two raters. Subsequently, the same article was independently coded by two additional raters. Coders extracted several objectively verifiable characteristics of the studies: (a) the number of participants and their composition by age, gender, marital status, distress level, health status, and pre-existing health conditions (if any), as well as the percentage of smokers and percentage of physically active individuals, and, of course, the cause of mortality; (b) the length of follow up; (c) the research design; and (d) the aspect of social relationships evaluated.

Data within studies were often reported in terms of odds ratios (ORs), the likelihood of mortality across distinct levels of social relationships. Because OR values cannot be meaningfully aggregated, all effect sizes reported within studies were transformed to the natural log OR (lnOR) for analyses and then transformed back to OR for interpretation. When effect size data were reported in any metric other than OR or lnOR, we transformed those values using statistical software programs and macros (e.g., Comprehensive Meta-Analysis [24]). In some cases when direct statistical transformation proved impossible, we calculated the corresponding effect sizes from frequency data in matrices of mortality status by social relationship status. When frequency data were not reported, we recovered the cell probabilities from the reported ratio and marginal probabilities. When survival analyses (i.e., hazard ratios) were reported, we calculated the effect size from the associated level of statistical significance, often derived from 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Across all studies we assigned OR values less than 1.00 to data indicative of increased mortality and OR values greater than 1.00 to data indicative of decreased mortality for individuals with relatively higher levels of social relationships.

When multiple effect sizes were reported within a study at the same point in time (e.g., across different measures of social relationships), we averaged the several values (weighted by standard error) to avoid violating the assumption of independent samples. In such cases, the aggregate standard error value for the lnOR were estimated on the basis of the total frequency data without adjustment for possible correlation among the averaged values. Although this method was imprecise, the manuscripts included in the meta-analysis did not report the information necessary to make the statistical adjustments, and we decided not to impute values given the wide range possible. In analyzing the data we used the shifting units of analysis approach [25] which minimizes the threat of nonindependence in the data while at the same time allowing more detailed follow-up analyses to be conducted (i.e., examination of effect size heterogeneity).

When multiple reports contained data from the same participants (publications of the same database), we selected the report containing the whole sample and eliminated reports of subsamples. When multiple reports contained the same whole sample, we selected the one with the longest follow-up duration. When multiple reports with the same whole sample were of the same duration, we selected the one reporting the greatest number of measures of social relationships.

In cases where multiple effect sizes were reported across different levels of social relationships (i.e., high versus medium, medium versus low), we extracted the value with the greatest contrast (i.e., high versus low). When a study contained multiple effect sizes across time, we extracted the data from the longest follow-up period. If a study used statistical controls in calculating an effect size, we extracted the data from the model utilizing the fewest statistical controls so as to remain as consistent as possible across studies (and we recorded the type and number of covariates used within each study to run post hoc comparative analyses). We coded the research design used rather than estimate risk of individual study bias. The coding protocol is available from the authors.

The majority of information obtained from the studies was extracted verbatim from the reports. As a result, the inter-rater agreement was quite high for categorical variables (mean Cohen's kappa = 0.73, SD = 0.13) and for continuous variables (mean intraclass correlation [26] = 0.80, SD = .14). Discrepancies across coding pairs were resolved through further scrutiny of the manuscript until consensus was obtained.

Aggregate effect sizes were calculated using random effects models following confirmation of heterogeneity. A random effects approach produces results that generalize beyond the sample of studies actually reviewed [27]. The assumptions made in this meta-analysis clearly warrant this method: The belief that certain variables serve as moderators of the observed association between social relationships and mortality implies that the studies reviewed will estimate different population effect sizes. Random effects models take such between-studies variation into account, whereas fixed effects models do not [28]. In each analysis conducted, we examined the remaining variance to confirm that random effects models were appropriate.

Results

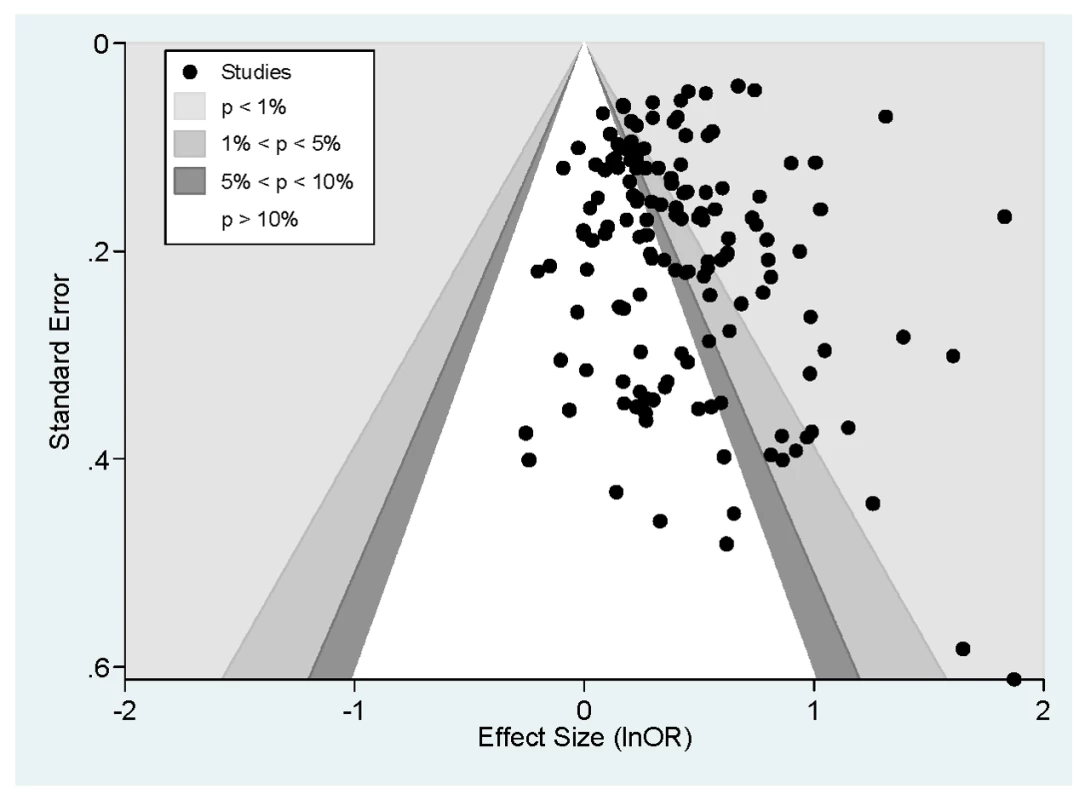

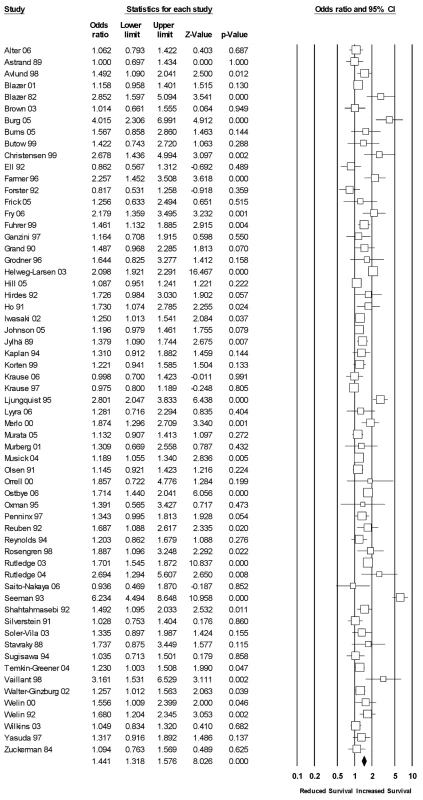

Statistically nonredundant effect sizes were extracted from 148 studies ([29]–[176]; see Table 1). Data were reported from 308,849 participants, with 51% from North America, 37% from Europe, 11% from Asia, and 1% from Australia. Across all studies, the average age of participants at initial evaluation was 63.9 years, and participants were evenly represented across sex (49% female, 51% male). Of the studies examined, 60% involved community samples, but 24% examined individuals receiving outpatient medical treatment, and 16% utilized patients in inpatient medical settings. Of studies involving patients with a pre-existing diagnosis, 44% were specific to cardiovascular disease (CVD), 36% to cancer, 9% to renal disease, and the remaining 11% had a variety of conditions including neurological disease. Research reports most often (81%) considered all-cause mortality, but some restricted evaluations to mortality associated with cancer (9%), CVD (8%), or other causes (2%). Participants were followed for an average of 7.5 years (SD = 7.1, range = 3 months to 58 years), with an average of 29% of the participants dying within each study's follow-up period.

Tab. 1. Overview of the 148 studies included in the meta-analysis.

Chi, chi-square; Combin, combined statistics; Freq, frequency counts; m, months; M & SD, means and standard deviations; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio; RR, risk ratio; p, level of statistical significance; t, t-scores; y, years. Omnibus Analysis

Across 148 studies, the random effects weighted average effect size was OR = 1.50 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.42 to 1.59), which indicated a 50% increased likelihood of survival as a function of stronger social relations. Odds ratios ranged from 0.77 to 6.50, with substantial heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 81% [95% CI = 78% to 84%]; Q(147) = 790, p<0.001; τ2 = 0.07), suggesting that systematic effect size variability was unaccounted for. Thus factors associated with the studies themselves (e.g., publication status), participant characteristics (e.g., age, health status), and the type of evaluation of social relationships (e.g., structural social networks versus perceptions of functional social support) may have moderated the overall results. We therefore conducted additional analyses to determine the extent to which these variables moderated the overall results.

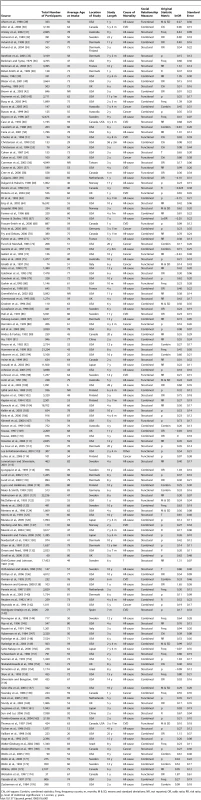

To assess the possibility of publication bias [177], we conducted several analyses. First, we calculated the fail-safe N [177] to be 4,274, which is the theoretical number of unpublished studies with effect sizes averaging zero (no effect) that would be needed to render negligible the omnibus results. Second, we employed the “trim and fill” methodology described by Duval and Tweedie [178],[179] to estimate the number of studies missing due to publication bias, but this analysis failed to reveal any studies that would need to be created on the opposite side of the distribution, meaning that adjustment to the omnibus effect size was unnecessary. Third, we calculated both Egger's regression test and the alternative to that test recommended by Peters and colleagues [180] that is better suited to data in lnOR format. The results of both analyses failed to reach statistical significance (p>0.05). Finally, we plotted a contour-enhanced funnel plot (Figure 2) [181]. The data obtained from this meta-analysis were fairly symmetrical with respect to their own mean; fewer than ten studies were “missing” on the left side of the distribution that would have made the plot symmetrical. Based on these several analyses, publication bias is unlikely to threaten the results.

Fig. 2. Contour enhanced funnel plot.

Moderation by Social Relationship Assessment, and by Participant and Study Characteristics

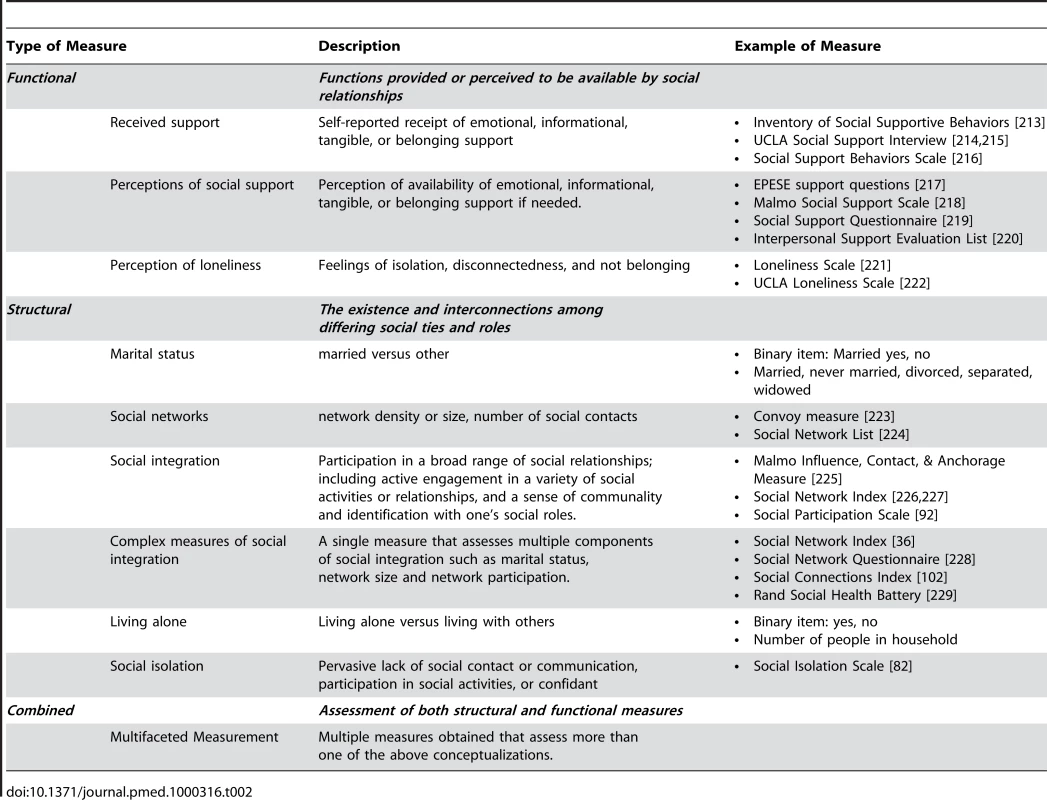

Given that structural versus functional components of social relationships may influence health in different ways [11],[12], the high degree of heterogeneity observed in the omnibus results may have been due in part to differences between the components of social relationships evaluated within and across studies. Hence the remaining analyses separately evaluate effect sizes obtained from structural, functional, and combined (structural and functional) measures of social relationships. Table 2 provides definitions of the types and subtypes of social relationships evaluated.

Tab. 2. Descriptive coding of the measures used to assess social relationships.

Structural aspects of social relationships

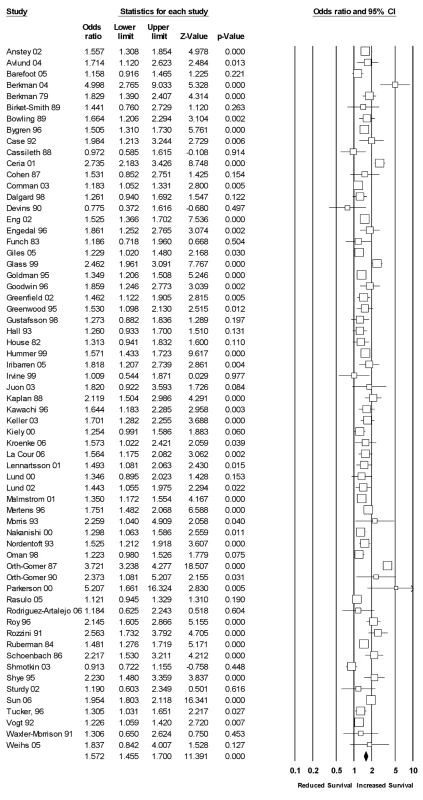

Sixty-three studies had data exclusive to structural measures of social relationships (see Figure 3). Across these studies, the random effects weighted average effect size was OR = 1.57 (95% CI = 1.46 to 1.70), which value fell within the CI of the omnibus results reported previously. The heterogeneity across studies was still quite large (I2 = 84% [95% CI = 80% to 87%]; Q(62) = 390, p<0.001; τ2 = 0.07), so we undertook metaregression with prespecified participant and study characteristics.

Fig. 3. Forest plot of structural measures.

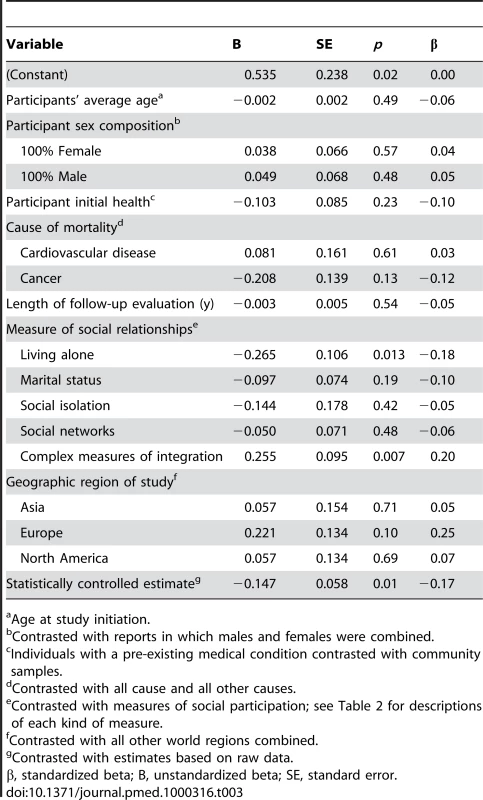

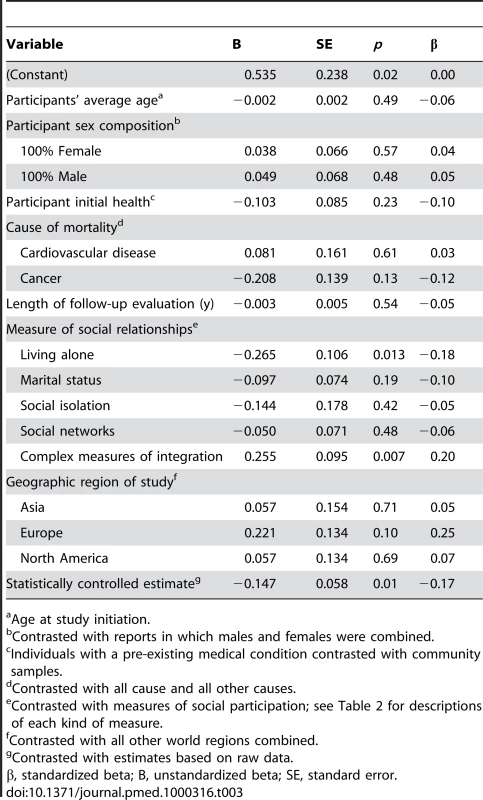

Metaregression is an analogue to multiple regression analysis for effect sizes. Its primary purpose is to ascertain which continuous and categorical (dummy coded) variables predict variation in effect size estimates. Using random effects weighted metaregression, we examined the simultaneous association (with all variables entered into the model) between effect sizes and prespecified participant and study characteristics (Table 3). To examine the most precise effect size estimates available and to increase the statistical power associated with this analysis, we shifted the unit of analysis [24] and extracted effect sizes within studies that were specific to measures of structural aspects of social relationships. That is, if a study contained effect sizes from both structural and functional types of social relationships, we extracted the structural types for this analysis (with identical subtypes aggregated), which resulted in a total of 230 unique effect sizes across 116 studies. A total of 18% of the variance in these effect sizes was explained in the metaregression (p<0.001). As can be seen in Table 3, effect sizes based on data controlling for other variables were lower in magnitude than those based on raw data. Moreover, effect sizes differed in magnitude across the subtype of structural social relationships measured. Complex measures of social integration were associated with larger effect size values than measures of social participation. Binary measures of whether participants lived alone (yes/no) were associated with smaller effect size values. Average random effects weighted odds ratios for the various subtypes of social relationships are reported in Table 4.

Tab. 3. Random effects metaregression for effect size estimates of structural social relationships.

Age at study initiation. Tab. 4. Weighted average effect sizes across different measures of social relationships.

These analyses shifted the units of analysis, with distinct effect size estimates within studies used within different categories of measurement, such that many studies contributed more than one effect size but not more than one per category of measurement. Functional aspects of social relationships

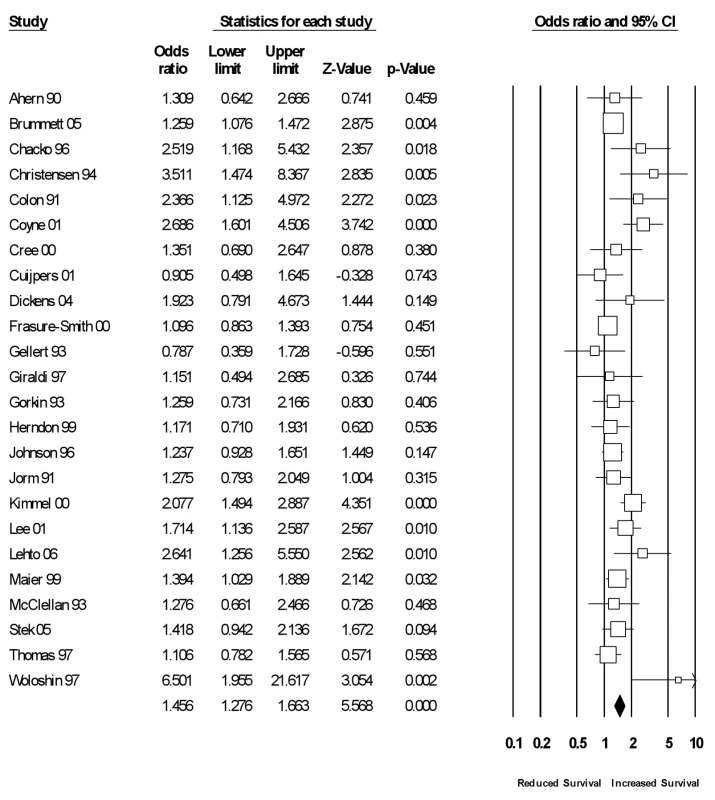

Twenty-four studies had data exclusive to functional measures of social relationships (see Figure 4). Across these studies, the random effects weighted average effect size was OR = 1.46 (95% CI = 1.28 to 1.66), which value fell within the CI of the omnibus results reported previously. There was moderate heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 47% [95% CI = 16% to 68%]; Q(23) = 44, p<0.01; τ2 = 0.04), so we conducted a random effects metaregression using the same variables and analytic procedures described previously. We extracted 87 unique effect sizes that were specific to measures of functional social relationships within 72 studies. A total of 16.5% of the variance in these effect sizes was explained in the metaregression, but the model did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.46). The results were not moderated by any of the specified participant characteristics (age, sex, initial health status, cause of mortality) or study characteristics (length of follow-up, geographic region, statistical controls).

Fig. 4. Forest plot of functional measures.

Combined assessments of social relationships

Sixty-one studies had combined data of both structural and functional measures of social relationships (see Figure 5). Across these studies, the random effects weighted average effect size was OR = 1.44 (95% CI = 1.32 to 1.58). A large degree of heterogeneity characterized studies (I2 = 82% [95% CI = 78% to 86%]; Q(60) = 337, p<0.001; τ2 = 0.09), and we conducted a random effects metaregression using the same variables and analytic procedures described previously. We extracted 64 unique effect sizes that evaluated combined structural and functional measures of social relationships within 61 studies. The metaregression explained only 6.8% of the variance in these effect sizes, and the model failed to reach statistical significance (p = 0.95). None of the variables in the metaregression moderated the results.

Fig. 5. Forest plot of combined measures.

Discussion

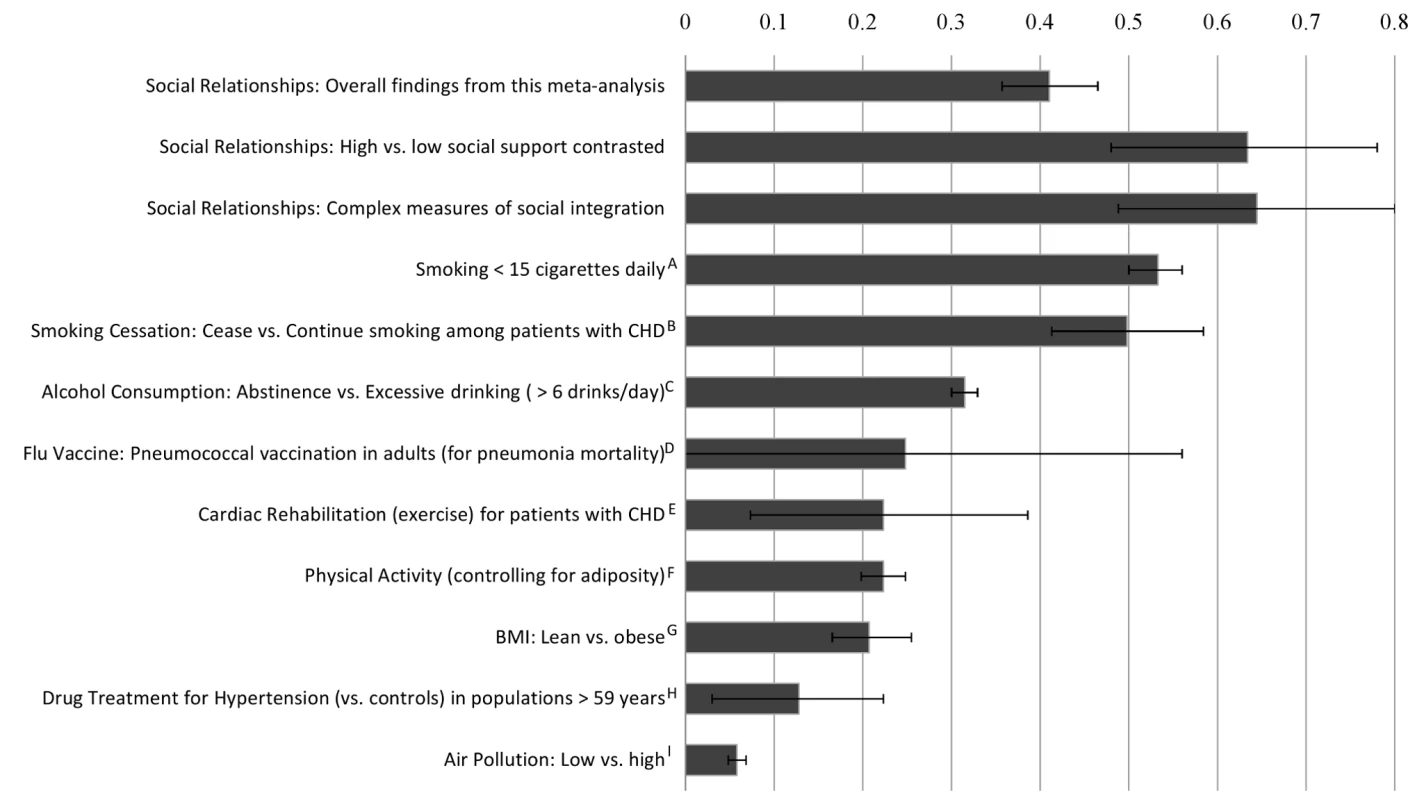

Cumulative empirical evidence across 148 independent studies indicates that individuals' experiences within social relationships significantly predict mortality. The overall effect size corresponds with a 50% increase in odds of survival as a function of social relationships. Multidimensional assessments of social integration yielded an even stronger association: a 91% increase in odds of survival. Thus, the magnitude of these findings may be considered quite large, rivaling that of well-established risk factors (Figure 6). Results also remained consistent across a number of factors, including age, sex, initial health status, follow-up period, and cause of death, suggesting that the association between social relationships and mortality may be generalized.

Fig. 6. Comparison of odds (lnOR) of decreased mortality across several conditions associated with mortality.

Note: Effect size of zero indicates no effect. The effect sizes were estimated from meta analyses: ; A = Shavelle, Paculdo, Strauss, and Kush, 2008 [205]; B = Critchley and Capewell, 2003 [206]; C = Holman, English, Milne, and Winter, 1996 [207]; D = Fine, Smith, Carson, Meffe, Sankey, Weissfeld, Detsky, and Kapoor, 1994 [208]; E = Taylor, Brown, Ebrahim, Jollife, Noorani, Rees et al., 2004 [209]; F, G = Katzmarzyk, Janssen, and Ardern, 2003 [210]; H = Insua, Sacks, Lau, Lau, Reitman, Pagano, and Chalmers, 1994 [211]; I = Schwartz, 1994 [212]. The magnitude of risk reduction varied depending on the type of measurement of social relationships (see Table 4). Social relationships were most highly predictive of reduced risk of mortality in studies that included multidimensional assessments of social integration. Because these studies included more than one type of social relationship measurement (e.g., network based inventories, marital status, etc.), such a measurement approach may better represent the multiple pathways (described earlier) by which social relationships influence health and mortality [182]. Conversely, binary evaluations of living alone (yes/no) were the least predictive of mortality status. The reliability and validity of measurement likely explains this finding, and researchers are encouraged to use psychometrically sound measures of social relationships (e.g., Table 2). For instance, while researchers may be tempted to use a simple single-item such as “living alone” as a proxy for social isolation, it is possible for one to live alone but have a large supportive social network and thus not adequately capture social isolation. We also found that social isolation had a similar influence on likelihood of mortality compared with other measures of social relationships. This evidence qualifies the notion of a threshold effect (lack of social relationships is the only detrimental condition); rather, the association appears robust across a variety of types of measures of social relationships.

This meta-analysis also provides evidence to support the directional influence of social relationships on mortality. Most of the studies (60%) involved community cohorts, most of whom would not be experiencing life-threatening conditions at the point of initial evaluation. Moreover, initial health status did not moderate the effect of social relationships on mortality. Although illness may result in poorer or more restricted social relationships (social isolation resulting from physical confinement), such that individuals closer to death may have decreased social support compared to healthy individuals, the findings from these studies indicate that general community samples with strong social relationships are likely to remain alive longer than similar individuals with poor social relations. However, causality is not easily established. One cannot randomly assign human participants to be socially isolated, married, or in a poor-quality relationship. A similar dilemma characterizes virtually all lifestyle risk factors for mortality: for instance, one cannot randomly assign individuals to be smokers or nonsmokers. Despite such challenges, “smoking represents the most extensively documented cause of disease ever investigated in the history of biomedical research” [183]. The link between social relationships and mortality is currently much less understood than other risk factors; nonetheless there is substantial experimental, cross-sectional, and prospective evidence linking social relationships with multiple pathways associated with mortality (see [182] for review). Existing models for reducing risk of mortality may be substantially strengthened by including social relationship factors.

Notably, the overall effect for social relationships on mortality reported here may be a conservative estimate. Many studies included in the meta-analysis utilized single item measures of social relations, yet the magnitude of the association was greatest among those studies utilizing complex assessments. Moreover, because many studies statistically adjusted for standard risk factors, the effect may be underestimated, since some of the impact of social relationships on mortality may be mediated through such factors (e.g., behavior, diet, exercise). Additionally, most measures of social relations did not take into account the quality of the social relationships, thereby assuming that all relationships are positive. However, research suggests this is not the case, with negative social relationships linked to greater risk of mortality [184],[185]. For instance, marital status is widely used as a measure of social integration; however, a growing literature documents its divergent effects based on level of marital quality [186],[187]. Thus the effect of positive social relationships on risk of mortality may actually be much larger than reported in this meta-analysis, given the failure to account for negative or detrimental social relationships within the measures utilized across studies.

Other possible limitations of this review should be acknowledged. Statistical controls (e.g., age, sex, physical condition, etc.) employed by many of the studies rule out a number of potentially confounding variables that might account for the association between social relationships and mortality. However, studies used an inconsistent variety of controlling variables, and some reports involved raw data (Table 1). Although effect size magnitude was diminished by the inclusion of statistical controls only within the data obtained by measures of structural social relationships (but not functional or combined measures), future research can better specify which variables are most likely to impact the overall association. It must also be acknowledged that existing data primarily represent research conducted in North America and Western Europe. Although we found no differences across world region, future reviews inclusive of research written in all languages (not only English) with participants better representing other world regions may yield better estimates across populations.

Approximately two decades after the review by House and colleagues [1], a generation of empirical research validates their initial premise: Social relationships exert an independent influence on risk for mortality comparable with well established risk factors for mortality (Figure 6). Although limited by the state of current investigations and possible omission of pertinent reports, this meta-analysis provides empirical evidence (nearly 30 times the number of studies previously reported) to support the criteria for considering insufficient social relationships a risk factor of mortality (i.e., strength and consistency of association across a wide range of studies, temporal ordering, and gradient of response) [188]. The magnitude of the association between social relationships and mortality has now been established, and this meta-analysis provides much-needed clarification regarding the social relationship factor(s) most predictive of mortality. Future research can shift to more nuanced questions aimed at (a) understanding the causal pathways by which social participation promotes health, (b) refining conceptual models, and (c) developing effective intervention and prevention models that explicitly account for social relations.

Some steps have already been taken identifying the psychological, behavioral, and physiological pathways linking social relationships to health [5],[182],[189]. Social relationships are linked to better health practices and to psychological processes, such as stress and depression, that influence health outcomes in their own right [190]; however, the influence of social relationships on health cannot be completely explained by these processes, as social relationships exert an independent effect. Reviews of such findings suggest that there are multiple biologic pathways involved (physiologic regulatory mechanisms, themselves intertwined) that in turn influence a number of disease endpoints [182],[191]–[193]. For instance, a number of studies indicate that social support is linked to better immune functioning [194]–[197] and to immune-mediated inflammatory processes [198]. Thus interdisciplinary work and perspective will be important in future studies given the complexity of the phenomenon.

Perhaps the most important challenge posed by these findings is how to effectively utilize social relationships to reduce mortality risk. Preliminary investigations have demonstrated some risk reduction through formalized social interventions [199]. While the evidence is mixed [2],[6], it should be noted that most social support interventions evaluated in the literature thus far are based on support provided from strangers; in contrast, evidence provided in this meta-analysis is based almost entirely on naturally occurring social relationships. Moreover, our analyses suggest that received support is less predictive of mortality than social integration (Table 4). Therefore, facilitating patient use of naturally occurring social relations and community-based interventions may be more successful than providing social support through hired personnel, except in cases in which patient social relations appear to be detrimental or absent. Multifaceted community-based interventions may have a number of advantages because such interventions are socially grounded and include a broad cross-section of the public. Public policy initiatives need not be limited to those deemed “high risk” or those who have already developed a health condition but could potentially include low - and moderate-risk individuals earlier in the risk trajectory [200]. Overall, given the significant increase in rate of survival (not to mention quality of life factors), the results of this meta-analysis are sufficiently compelling to promote further research aimed at designing and evaluating interventions that explicitly account for social relationship factors across levels of health care (prevention, evaluation, treatment compliance, rehabilitation, etc.).

Conclusion

Data across 308,849 individuals, followed for an average of 7.5 years, indicate that individuals with adequate social relationships have a 50% greater likelihood of survival compared to those with poor or insufficient social relationships. The magnitude of this effect is comparable with quitting smoking and it exceeds many well-known risk factors for mortality (e.g., obesity, physical inactivity). These findings also reveal significant variability in the predictive utility of social relationship variables, with multidimensional assessments of social integration being optimal when assessing an individual's risk for mortality and evidence that social isolation has a similar influence on mortality to other measures of social relationships. The overall effect remained consistent across a number of factors, including age, sex, initial health status, follow-up period, and cause of death, suggesting that the association between social relationships and mortality may be general, and efforts to reduce risk should not be isolated to subgroups such as the elderly.

To draw a parallel, many decades ago high mortality rates were observed among infants in custodial care (i.e., orphanages), even when controlling for pre-existing health conditions and medical treatment [201]–[204]. Lack of human contact predicted mortality. The medical profession was stunned to learn that infants would die without social interaction. This single finding, so simplistic in hindsight, was responsible for changes in practice and policy that markedly decreased mortality rates in custodial care settings. Contemporary medicine could similarly benefit from acknowledging the data: Social relationships influence the health outcomes of adults.

Physicians, health professionals, educators, and the public media take risk factors such as smoking, diet, and exercise seriously; the data presented here make a compelling case for social relationship factors to be added to that list. With such recognition, medical evaluations and screenings could routinely include variables of social well-being; medical care could recommend if not outright promote enhanced social connections; hospitals and clinics could involve patient support networks in implementing and monitoring treatment regimens and compliance, etc. Health care policies and public health initiatives could likewise benefit from explicitly accounting for social factors in efforts aimed at reducing mortality risk. Individuals do not exist in isolation; social factors influence individuals' health though cognitive, affective, and behavioral pathways. Efforts to reduce mortality via social relationship factors will require innovation, yet innovation already characterizes many medical interventions that extend life at the expense of quality of life. Social relationship–based interventions represent a major opportunity to enhance not only the quality of life but also survival.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HouseJS

LandisKR

UmbersonD

1988 Social relationships and health. Science 241 540 545

2. BerkmanLF

BlumenthalJ

BurgM

2003 Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. JAMA 289 3106 3116

3. McPhersonM

Smith-LovinL

2006 Social Isolation in America: Changes in core discussion networks over two decades. Am Sociol Rev 71 353 375

4. PutnamRD

2000 Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community New York, NY, US Simon & Schuster

5. CohenS

GottliebBH

UnderwoodLG

2000 Social Relationships and Health.

CohenS

UnderwoodLG

GottliebBH

Measuring and intervening in social support New York Oxford University Press 3 25

6. CohenS

GottliebBH

UnderwoodLG

2001 Social relationships and health: challenges for measurement and intervention. Adv Mind Body Med 17 129 141

7. CohenS

2004 Social relationships and health. Am Psychol 59 676 684

8. ThoitsPA

1983 Multiple identities and psychological well-being: A reformulation and test of the social isolation hypothesis. Am Sociol Rev 48 174 187

9. BrissetteI

CohenS

SeemanTE

2000 Measuring social integration and social networks.

CohenS

UnderwoodLG

GottliebBH

Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists New York, NY, US Oxford University Press 53 85

10. ReinhardtJP

BoernerK

HorowitzA

2006 Good to have but not to use: Differential impact of perceived and received support on well-being. J Soc Pers Relat 23 117 129

11. LakeyB

CohenS

2000 Social support theory and measurement.

CohenS

UnderwoodLG

GottliebBH

Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists New York, NY, US Oxford University Press 29 52

12. CohenS

GottliebBH

UnderwoodLG

2000 Social relationships and health.

CohenS

UnderwoodLG

GottliebBH

Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists New York, NY, US Oxford University Press 3 25

13. DiMatteoMR

2004 Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 23 207 218 (2004)

14. MurphyBM

ElliottPC

Le GrandeMR

HigginsRO

ErnestCS

2008 Living alone predicts 30-day hospital readmission after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 15 210 215

15. LettHS

BlumenthalJA

BabyakMA

CatellierDJ

CarneyRM

2007 Social support and prognosis in patients at increased psychosocial risk recovering from myocardial infarction. Health Psychol 26 418 427

16. KnoxSS

AdelmanA

EllisonRC

ArnettDK

SiegmundK

2000 Hostility, social support, and carotid artery atherosclerosis in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study. Am J Cardiol 86 1086 1089

17. KopWJ

BermanDS

GransarH

WongND

Miranda-PeatsR

2005 Social network and coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic individuals. Psychosom Med 67 343 352

18. BrummettBH

BarefootJC

SieglerIC

Clapp-ChanningNE

LytleBL

2001 Characteristics of socially isolated patients with coronary artery disease who are at elevated risk for mortality. Psychosom Med 63 267 272

19. WangHX

MittlemanMA

LeineweberC

Orth-GomerK

2006 Depressive symptoms, social isolation, and progression of coronary artery atherosclerosis: the Stockholm Female Coronary Angiography Study. Psychother Psychosom 75 96 102

20. WangHX

MittlemanMA

Orth-GomerK

2005 Influence of social support on progression of coronary artery disease in women. Soc Sci Med 60 599 607

21. AngererP

SiebertU

KothnyW

MuhlbauerD

MudraH

2000 Impact of social support, cynical hostility and anger expression on progression of coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 36 1781 1788

22. KnoxSS

Uvnas-MobergK

1998 Social isolation and cardiovascular disease: an atherosclerotic pathway? Psychoneuroendocrinology 23 877 890

23. CohenS

WillsTA

1985 Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 98 310 357

24. BorensteinM

HedgesL

HigginsJ

RothsteinH

2005 Comprehensive Meta-analysis Version 2, Biostat, Englewood NJ

25. CooperH

1998 Synthesizing research: A guide for literature reviews 3rd ed Thousand Oaks Sage

26. ShroutPE

FleissJL

1979 Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 86 420 428

27. HedgesLV

VeveaJL

1998 Fixed - and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods 3 486 504

28. MostellerF

ColditzGA

1996 Understanding research synthesis (meta-analysis). Annual Review of Public Health 17 1 23

29. AhernD

GorkinL

AndersonJ

TierneyC

HallstromA

1990 Biobehavioral variables and mortality or cardiac arrest in the cardiac arrhythmia pilot study (CAPS). Am J Cardiol 66 59 62

30. AlterDA

ChongA

AustinPC

MustardC

IronK

2006 Socioeconomic status and mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 144 82 93

31. AnsteyJK

LuszczMA

2002 Mortality risk varies according to gender and change in depressive status in very old adults. Psychosom Med 64 880 888

32. AstrandNE

HansonBS

IsacssonSO

1989 Job demands, job decision latitude, job support, and social network factors as predictors of mortality in a Swedish pulp and paper company. Br J Ind Med 46 334 340

33. AvlundK

DamsgaardMT

HolsteinBE

1998 Social relations and mortality. An eleven year follow-up studey of 70 year-old men and women in Denmark. Soc Sci Med 47 635 643

34. AvlundK

LundR

HolsteinBE

DueP

Sakari-RantalaR

2004 The impact of structural and functional characteristics of social relations as determinants of functional decline. J Gerontol 59B s44 s51

35. BarefootJC

GrobaekM

JensenG

Schnohr

PrescottE

2005 Social network diversity and risks of ischemic heart disease and total mortality: Findings from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Ame J Epidemiol 161 960 967

36. BerkmanLF

SymeSL

1979 Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol 109 186 204

37. BerkmanLF

MelchiorM

ChastangJF

NiedhammerI

LeclercA

2004 Social integration and mortality: A prospective study of French employees of electricity of France-Gas of France: the GAZEL Cohort. Ame J Epidemiol 159 167 174

38. Birket-SmithM

KnudsenHC

NissenJ

BlegvadN

KøhlerO

1989 Life events and social support in prediction of stroke outcome. Psychother Psychosom 52 146 150

39. BlazerDG

1982 Social support and mortality in an elderly community population. Am J Epidemiol 115 684 694

40. BlazerD

HybelsC

PieperC

2001 The association of depression and mortality in elderly persons: a case for multiple, independent pathways. J Gerontol: Medical Sciences, 56A M505 M509

41. BowlingA

1989 Who dies after widow(er)hood? A discriminant analysis. Omega 19 135 153

42. BrownSL

NesseRM

VinokurAD

SmithDM

2003 Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychol Sci 14 320 327

43. BrummettBH

MarkDB

SieglerIC

WilliamsRB

BabyakMA

2005 Perceived social support as a predictor of mortality of coronary patients: Effects of smoking, sedentary behavior, and depressive symptoms. Psychosom Med 67 40 45

44. BurgMM

BarefootJ

BerkmanL

CatellierDJ

CzajkowskiS

2005 ENRICHD Investigators. Low perceived social support and post-myocardial infarction prognosis in the enhancing recovery in coronary heart disease clinical trial: The effects of treatment. Psychosom Med 67 879 888

45. BurnsCM

CraftPS

RoderDM

2005 Does emotional support influence survival? Findings from a longitudinal study of patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 13 295 302

46. ButowPN

CoatesAS

DunnSM

1999 Psychosocial predictors of survival in Metastatic Melanoma. J Clin Oncol 17 2256 2263

47. BygrenLO

KonlaanBB

JohanssonS

1996 Attendance at cultural events, reading books or periodicals, and making music or singing in a choir as determinants for survival: Swedish interview survey of living conditions. BMJ 313(7072) 1577 1580

48. CaseRB

MossAJ

CaseN

McDermottM

EberlyS

1992 Living alone after myocardial infarction. JAMA 267 515 519

49. CassilethBR

WalshWP

LuskEJ

1988 Psychosocial correlates of cancer survival: A subsequent report 3 to 8 years after cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 6 1753 1759

50. CeriaCD

MasakiKH

RodriguezBL

ChenR

YanoK

2001 The relationship of psychosocial factors to total mortality among older Japanese-American men: The Honolulu Heart Program. J Am Geriatr Soc 49 725 731

51. ChackoRC

HarperRG

GottoJ

1996 Young J. Psychiatric interview and psychometric predictors of cardiac transplant survival. Am J Psychiatry 153 1607 1612

52. ChristensenAJ

DorninkR

EhlersSL

SchultzSK

1999 Social Environment and Longevity in Schizophrenia. Psychosom Med 61 141 145

53. ChristensenAJ

WiebeJS

SmithTW

TurnerCW

1994 Predictors of survival among hemodialysis patients: Effect of perceived family support. Health Psychol 13 521 525

54. CohenCI

TeresiJ

HolmesD

1987 Social networks and mortality in an inner-city elderly population. Int J Aging Hum Dev 24 257 269

55. ColonEA

CalliesAL

PopkinMK

McGlavePB

1991 Depressed mood and other variables related to bone marrow transplantation survival in acute leukemia. Psychosomatics 32 420 425

56. CornmanJC

GoldmanN

GleiDA

WeinsteinM

ChangM

2003 Social ties and perceived support: Two dimensions of social relationships and health among the elderly in Taiwan. J Aging Health 15 616 644

57. CoyneJC

RohrbaughMJ

ShohamV

SonnegaJS

NichlasJM

2001 Prognostic importance of marital quality for survival of congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 88 526 529

58. CreeM

SoskloneCL

BelseckE

HornigJ

McElhaneyJE

2000 Mortality and institutionalization following hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 48 283 288

59. CuijpersP

2000 Mortality and depressive symptoms in inhabitants of residential homes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 16 131 138

60. DalgardOS

HaheimLL

1998 Psychosocial risk factors and mortality: A prospective study with special focus on social support, social participation, and locus of control in Norway. J Epidemiol Community Health 52 476 481

61. DevinsGM

MannJ

MandinH

PaulLC

HonsRB

1990 Psychological predictors of survival in end-stage renal disease. J Nerv Ment Dis 178 127 133

62. DickensCM

McGowanL

PervicalC

DouglasJ

TomensonB

2004 Lack of close confidant, but not depression, predicts further cardiac events after myocardial infarction. Heart 90 518 522

63. EllK

NishimotoR

MedianskyL

MantellJ

HamovitchM

1992 Social relations, social support, and survival among patients with cancer. J Psychosom Res 36 531 541

64. EngPM

RimmEB

FitzmauriceG

KawachiI

2002 Social ties and change in social ties in relation to subsequent total and cause-specific mortality and coronary heart disease incidence in men. Ame J Epidemiol 155 700 709

65. EngedalK

1996 Mortality in the elderly–A 3-year follow-up of an elderly community sample. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 11 467 471

66. FarmerIP

MeyerPS

RamseyDJ

GoffDC

WearML

1996 Higher levels of social support predict greater survival following acute myocardial infarction: The Corpus Christi heart project. Behav Med 22 59 66

67. ForsterLE

StollerEP

1992 The impact of social support on mortality: A seven-year follow-up of older men and women. J App Gerontol 11 173 186

68. Frasure-SmithN

LesperanceF

GravelG

MassonA

JuneauM

2000 Social support, depression, and mortality during the first year after myocardial infarction. Circulation 101 1919 1924

69. FrickE

MotzkeC

FischerN

BuschR

BumederI

2005 Is perceived social support a predictor of survival from patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation? Psychooncology 14 759 770

70. FryPS

DebatsDL

2006 Sources of life strengths as predictors of late-life mortality and survivorship. Int J Aging Hum Dev 62 303 334

71. FuhrerR

DufouilC

AntonucciTC

ShipleyJM

HeimerC

1999 Psychological disorder and mortality in French older adults: do social relations modify the association? Am J Epidemiol 149 116 126

72. FunchDP

MarshallJ

1983 The role of stress, social support and age in survival from breast cancer. J Psychosom Res 27 77 83

73. GanziniL

SmithDM

FennDS

LeeMA

1997 Depression and mortality in medically ill older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 45 307 312

74. GellertGA

MaxwellRM

SiegelBS

1993 Survival of breast cancer patients receiving adjunctive psychosocial support therapy: A 10-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 11 66 69

75. GilesLC

GlonekGFV

LuszczMA

AndrewsGR

2004 Effects of social networks on 10 year survival in very old Australians: The Australian longitudinal study of aging. J Epidemiol Community Health 59 547 579

76. GiraldiT

RodaniMG

CartelG

GrassiL

1997 Psychosocial factors and breast cancer: A 6-year Italian follow-up study. Psychother Psychosom 66 229 236

77. GlassTA

Mendes de LeonC

MarottoliRA

BerkmanLF

1999 Population based study of social and productive activities as predictors of survival among elderly Americans. BM J 319 478 483

78. GoldmanN

KorenmanS

WeinsteinR

1995 Marital status and health among the elderly. Soc Sci Med 40 1717 1730

79. GoodwinJS

SametJM

HuntWC

1996 Determinants of Survival in Older Cancer Patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 88 1031 1038

80. GorkinL

SchronEB

BrooksMM

WiklundI

KellenJ

1993 Psychosocial predictors of mortality in the cardiac arrhythmia suppression trial-1 (CAST-1). Am J Cardiol 71 263 267

81. GrandA

GrosclaudeP

BocquetH

PousJ

AlbaredeJL

1990 Disability, psychosocial factors, and mortality among the elderly in a rural French population. J Clin Epidemiol 43 773 783

82. GreenfieldTK

RehmJ

RogersJD

2002 Effects of depression and social integration on the relationship between alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality. Addiction 97 29 38

83. GreenwoodD

PackhamC

MuirK

MadeleyR

1995 How do economic status and social support influence survival after initial recovery from acute myocardial infarction? Soc Sci Med 40 639 647

84. GrodnerS

PrewittLM

JaworskiBA

MyersR

KaplanR

1996 The impact of social support in pulmonary rehabilitation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Behav Med 18 139 145

85. GustafssonTM

IsacsonDGL

ThorslundM

1998 Mortality in elderly men and women in a Swedish municipality. Age Ageing 27 584 593

86. HallEM

JohnsonJV

TsouTS

1993 Women, occupation, and risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Occup Med 8 709 718

87. Helweg-LarsenM

KjollerM

ThonigH

2003 Do age and social relations moderate the relationship between self-rated health and mortality among adult Danes. Soc Sci Med 57 1237 1247

88. HerndonJE

FleishmanS

KornblithAB

KostyM

GreenMR

1999 Is quality of life predictive of the survival of patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer 85 333 340

89. HillTD

AngelJL

EllisonCG

AngelRJ

2005 Religious attendance and mortality: An 8-year follow-up of older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol 60B S102 S109

90. HirdesJP

ForbesWF

1992 The importance of social relationships, socioeconomic status, and health practices with respect to mortality among healthy Ontario males. J Clin Epidemiol 45 175 182

91. HoSC

1991 Health and social predictors of mortality in an elderly Chinese cohort. Ame J Epidemiol 133 907 921

92. HouseJS

RobbinsC

MetznerHL

1982 The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: Prospective evidence from the Tecumseh community health study. Ame J Epidemiol 116 123 140

93. HummerRA

RogersRG

NamCB

EllisonCG

1999 Religious involvement and U.S. adult mortality. Demography 36 273 285

94. IribarrenC

JacobsDR

KiefeCI

LewisCE

MatthewsKA

2005 Causes and demographic, medical, lifestyle and psychosocial predictors of premature mortality: The CARDIA study. Soc Sci Med 60 471 482

95. IrvineJ

BasinskiA

BakerB

JandciuS

PaquetteM

1999 Depression and risk of sudden cardiac death after acute myocardial infarction: testing for the confounding effects of fatigue. Psychosom Med 61 729 737

96. IwasakiM

OtaniT

SunagaR

MiyazakiH

XiaoL

2002 Social networks and mortality base on the Komo-ise cohort study in Japan. Int J Epidemiol 31 1208 1218

97. JohnsonJE

FinneyJW

MoosRH

2005 Predictors of 5-year mortality following inpatients/residential group treatment of substance use disorders. Addict Behav 30 1300 1316

98. JohnsonJV

StewartW

HallEM

FredlundP

TheorellT

1996 Long-term psychosocial work environment and cardiovascular mortality among Swedish men. Am J Public Health 86 324 331

99. JormAF

HendersonAS

KayDWK

JacombPA

1991 Mortality in relation to dementia, depression, and social integration in an elderly community sample. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 6 5 11

100. JuonH

EnsmingerME

FeehanM

1989 Childhood adversity and later mortality in an urban African American cohort. Am J Public Health 93 2044 2046

101. JylhäM

AroS

1989 Social ties and survival among the elderly in Tampere, Finland. Int J Epidemiol 18 158 173

102. KaplanGA

SalonenJT

CohenRD

BrandRJ

SymeSL

1988 Social connections and mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease: Prospective evidence from eastern Finland. Ame J Epidemiol 28 370 380

103. KaplanGA

WilsonTW

CohenRD

KauhanenJ

WuM

1994 Social functioning and overall mortality: Prospective evidence from the Kuipio ischemic heart disease risk factor study. Epidemiology 5(5) 495 500

104. KawachiI

ColditzGA

AscherioA

RimmEB

GiovannucciE

1996 A prospective study of social networks in relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease in men in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health 50 245 251

105. KellerBK

MagnusonTM

CerninPA

StonerJA

PotterJF

2003 The significance of social network in a geriatric assessment population. Aging Clin Exp Res 15 512 517

106. KielyDK

SimonSE

JonesRN

MorrisJN

2000 The protective effect of social engagement on mortality in long-term care. J Am Geriatr Soc 48 1367 1372

107. KimmelPL

PetersonRA

WeihsKL

ShidlerN

SimmensSJ

2000 Dyadic relationship conflict, gender, and mortality in Urban hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 11(8) 1518 1525

108. KortenAE

JormAF

JaioZ

LetenneurL

JacombPA

1999 Health, cognitive, and psychosocial factors as predictors of mortality in an elderly community sample. J Epidemiol Community Health 53 83 88

109. KrauseN

1997 Received support, anticipated support, social class, and mortality. Res Aging 19 387 422

110. KrauseN

2006 Church-based social support and mortality. J Gerontol 61B(3) S140 S146

111. KroenkeCH

KubzanskyLD

SchernhammerES

HolmesMD

KawachiI

2006 Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 24 1105 1111

112. La CourP

AvlundK

Schultz-LarsenK

2005 Religion and survival in a secular region. A twenty year follow-up of 734 Danish adults born in 1914. Soc Sci Med 62 157 164

113. LeeM

Rotheram-BorusMJ

2001 Challenges associated with increased survival among parents living with HIV. Am J Public Health 91 1303 1309

114. LehtoUS

OjanenM

DybaT

AromaaA

Kellokumpu-LehtinenP

2006 Baseline psychosocial predictors of survival in localized breast cancer. Br J Cancer 94 1245 1252

115. LennartssonC

SilversteinM

2001 Does engagement with life enhance survival of elderly people in Sweden? The role of social and leisure activities. J Gerentol 56B S335 S342

116. LjungquistB

BergS

SteenB

1995 Prediction of survival in 70-year olds. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 20 295 307

117. LundR

DueP

ModvigJ

HolsteinBE

DamsgaardMT

2002 Cohabitation and marital status as predictors of mortality–an eight year follow-up study. Soc Sci Med 55 673 679

118. LundR

ModvigJ

DueP

HolsteinBE

2000 Stability and change in structural social relations as predictor or mortality among elderly women and men. Eur J Epidemiol 16 1087 1097

119. LyyraT

HeikkinenR

2006 Perceived social support and mortality in older people. J Gerontol 61B S147 S152

120. MaierD

SmithJ

1999 Psychological predictors of mortality in old age. J Gerontol: Series B: Psychol Scis & Social Sciences 54B 44 54

121. MalmstromM

JohanssonS

SundquistJ

2001 A hierarchical analysis of long-term illness and mortality in socially deprived areas. Soc Sci Med 3 265 275

122. McClellanWM

StanwyckDJ

AnsonCA

1993 Social support and subsequent mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 4 1028 1034

123. MerloJ

OstergrenP

ManssonN

HansonBS

RanstamJ

2000 Mortality in elderly men with low psychosocial coping resources using anxiolytic-hypnotic drugs. 1403–4948 28 294 297

124. MertensJR

MoosRH

BrennanPL

1996 Alcohol consumption, life context, and coping predict mortality among late-middle-aged drinkers and former drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 20 313 319

125. MorrisPLP

RobinsonRG

AndrzejewskiP

SamuelsJ

PriceTR

1993 Association of depression with 10-year post stroke mortality. Am J Psychiatry 150 124 129

126. MurataC

KondoT

HoriY

MiyaoD

TamakoshiK

2005 Effects of social relationships on mortality among the elderly in a Japanese rural area: An 88-month follow-up study. J Epidemiol 15 78 84

127. MurbergTA

BruE

2001 Social relationships and mortality in patients with congestive heart failure. J Psychosom Res 51 521 527

128. MusickMA

HouseJS

WilliamsDR

2004 Attendance at religious services and mortality in a national sample. J Health Soc Behav 45 198 213

129. NakanishiN

TataraK

2000 Correlates and prognosis in relation to participation in social activities among older people living in a community in Osaka, Japan. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology 6 299 307

130. NordentoftM

BreumL

MunckLK

NordestgaardAG

HundingA

BjaeldagerPAL

1993 High mortality by natural and unnatural causes: A 10 year follow up study of patients admitted to a poisoning treatment centre after suicide attempts. Br Med J 306(6893) 1637 1641

131. OlsenRB

OlsenJ

Gunner-SvenssonF

WaldstromB

1991 Social networks and longevity: A 14 year follow-up study among elderly in Denmark. Soc Sci Med 33 1189 1195

132. OmanD

ReedD

1998 Religion and mortality among the community-dwelling elderly. Am J Public Health 88 1469 1475

133. OrrellM

ButlerR

BebbingtonP

2000 Social factors and the outcome of dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 15 515 520

134. Orth-GomerK

JohnsonJV

1987 Social network interaction and mortality. J Chronic Dis 40 949 957

135. Orth-GomerK

UndenAL

1990 Type A behavior, social support, and coronary risk: Interaction and significance for mortality in cardiac patients. Psychosom Med 52 59 72

136. OstbyeT

KrauseKM

NortonMC

TschanzJ

SandersL

2006 Cache County Investigators, Ten dimensions of health and their relationships with overall self-reported health and survival in a predominately religiously active elderly population: The Cache County memory study. J Am Geriatr Soc 54 199 209

137. OxmanTE

FreemanDH

ManheimerED

1995 Lack of social participation or religious strength and comfort as risk factors for death after cardiac surgery in the elderly. Psychosom Med 57 5 15

138. ParkersonGR

GutmanRA

2000 Health-related quality of life predictors of survival and hospital utilization. Health Care Financ Rev 21 171 184

139. PennixBWJH

TilburgT

KriegsmanDMW

DeegDJH

1997 Effects of social support and personal coping resources on mortality in older age: The longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. Am J Epidemiol 146 510 519

140. RasuloD

ChristensenK

TomassiniC

2005 The influence of social relations on mortality in later life: A study on elderly Danish twins. Gerontologist 45 601 609

141. ReubenDB

RubensteinLV

HirschSH

HaysRD

1992 Value of functional status as a predictor of mortality: Results of a prospective study. Am J Med 93 663 669

142. ReynoldsP

BoydPT

BlacklowRS

JacksonJS

GreenbergRS

1994 The relationship between social ties and survival among Black and White breast cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1055–9965 3 252 259

143. Rodriguez-ArtalejoF

Guallar-CastillonP

HerreraMC

OteroCM

ChivaMO

2006 Social network as a predictor of hospital readmission and mortality among older patients with heart failure. J Card Fail 12 621 627

144. RosengrenA

Orth-GomerK

WilhelmsenL

1998 Socioeconomic differences in health indices, social networks and mortality among Swedish men: A study of men born in 1933. Scand J Soc Med 26 272 280

145. RoyAW

FitzGibbonPA

HaugMM

1996 Social support, household composition, and health behaviors as risk factors for four-year mortality in an urban elderly cohort. J App Gerontol 15 73 86

146. RozziniR

BianchettiA

FranzoniS

ZanettieO

TrabucchiM

1991 Social, functional, and health status influences on mortality: Consideration of a multidimensional inquiry in a large elderly population. J Cross Cult Gerontol 6 83 90

147. RubermanW

WeinblattE

GoldbergJD

ChaudharyBS

1984 Psychosocial influences on mortality after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 9 552 559

148. RutledgeT

MatthewsK

LuiL

StoneKL

CauleyJA

2003 Social networks and marital status predict mortality in older women: Prospective evidence from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF). Psychosom Med 65 688 694

149. RutledgeT

ReisSE

OlsonM

OwensJ

KelseySF

2004 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Social networks are associated with lower mortality rates among women with suspected coronary disease: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation Study. Psychosom Med 66 882 888

150. Saito-NakayaK

NakayaN

FujimoriM

AkizukiN

YoshikawaE

KobayakawaM

NagaiK

NishiwakiN

TsubonoY

UchitomiY

2006 Marital status, social support and survival after curative resection in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci 97 206 213

151. SchoenbachVJ

KaplanBH

FredmanL

KleinbaumDG

1986 Social ties and mortality in Evans County, Georgia. Am J Epidemiol 123 577 591

152. SeemanT

BerkmanL

KohoutF

LacroixA

GlynnR

1993 Intercommunity variations in the association between social ties and mortality in the elderly: A comparative analysis of three communities. Eur Psychiatry 4 325 335

153. ShahatahmasebiS

DaviesR

WengerGC

1992 A longitudinal analysis of factors related to survival in old age. Gerontologist 32 404 413

154. ShmotkinD

BlumsteinT

ModanB

2003 Beyond keeping active: Concomitants of being a volunteer in old-old age. Psychol Aging 18 602 607

155. ShyeD

MulloolyJP

FreebornDK

PopeCR

1995 Gender differences in the relationship between social network support and mortality: A longitudinal study of an elderly cohort. Soc Sci Med 41 935 947

156. SilversteinM

BengtsonVL

1991 Do close parent-child relations reduce the mortality risk of older parents? J Health Soc Behav 32 382 395

157. Soler-VilaH

KaslSV

JonesBA

2003 Prognostic significance of psychosocial factors in African-American and White breast cancer patients: A population based study. Cancer 98 1299 1308

158. StavrakyKM

DonnerAP

KincadeJE

StewartMA

1988 The effect of psychosocial factors on lung cancer mortality at one year. J Clin Epidemiol 41 75 82

159. StekML

VinkersDJ

GusseklooJ

BeekmanATF

Van der MastRC

2005 Is depression in old age fatal only when people feel lonely? The Am J Psychiatry 162 178 180

160. SturdyPM

VictorCR

AndersonHR

BlandJM

ButlandBK

2002 Psychological, social and health behavior risk factors for deaths certified as asthma: A national case-control study. Thorax 57 1034 1039

161. SugisawaH

LiangJ

LiuX

1994 Social networks, social support, and mortality among older people in Japan. J Gerontol 49 S3 S13

162. SunR

LiuY

2006 Mortality of the oldest old in China: The role of social and solitary customary activities. J Aging Health 18 37 55

163. Temkin-GreenerH

BajorskaA

PetersonDR

KunitzSJ

GrossD

2004 Social support and risk-adjusted mortality in a frail, older population. Med Care 42 779 788

164. ThomasSA

FriedmannE

WimbushF

SchronE

1997 Psychosocial factors and survival in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST): A reexamination. Am J Crit Care 6 116 126

165. TuckerJS

FriedmanHS

WingardDL

SchwartzJE

1996 Marital history at midlife as a predictor of longevity: alternative explanations to the protective effects of marriage. Health Psychol 15 94 101

166. VaillantGE

MeyerSE

MukaamalK

SoldzS

1998 Are social supports in late midlife a cause or a result of successful physical ageing? Psychol Med 28 1159 1168

167. VogtTM

MulloollyDE

ErnstE

PopeCR

HollisJF

1992 Social networks as predictors of ischemic heart disease, cancer, stroke, and hypertension: incidence, survival, and mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 45 659 666

168. Walter-GinzburgA

BlumsteinT

ChetritA

ModanB

2002 Social factors and mortality in old-old in Israel: The CALAS study. J Gerontol 57b S308 S318

169. Waxler-MorrisonN

HislopG

MearsB

KanL

1991 Effects of social relationships on survival for women with breast cancer: A prospective study. Soc Sci Med 33 177 183

170. WeihsKL

SimmensSJ

MizrahiJ

EnrightTM

HuntME

2005 Dependable social relationships predict overall survival in stages II and III breast carcinoma patients. J Psychosom Res 59 299 306

171. WelinC

LappasG

WilhelmsenL

2000 Independent importance of psychosocial factors for prognosis after myocardial infarction. J Intern Med 247 629 639

172. WelinL

LarssonB

SvardsuddK

TibblinB

TibblinG

1992 Social network and activities in relation to mortality from cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and other causes: A 12 year follow up of the Study of Men Born in 1913 and 1923. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 46 127 132

173. WilkinsK

2003 Social support and mortality in seniors. Health Rep 14 21 34

174. WoloshinS

SchwartzLM

TostesonANA

ChangCH

WrightB

1997 Perceived adequacy of tangible social support and health outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. J Gen Intern Med 12 613 618

175. YasudaN

ZimmermanSI

HawkesW

FredmanL

HebelJR

1997 Relation of social network characteristics to 5-year mortality among young-old versus old-old White women in an urban community. Am J Epidemiol 145 516 523

176. ZuckermanDM

KaslSV

OstfeldAM

1984 Psychosocial predictors of mortality among the elderly poor. Am J Epidemiol 19 410 423

177. Rosenthal, The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull 86 638 641

178. DuvalS

TweedieR

2000 A non-parametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc 95 89 98

179. DuvalS

TweedieR

2000 Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56 455 463

180. PetersJL

SuttonAJ

JonesDR

AbramsKR

RushtonL

2006 Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA 295 676 680

181. PetersJ

SuttonA

JonesD

AbramsK

RushtonL

Contour-enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. Journal Of Clinical Epidemiology October 2008;61 991 996

182. UchinoBN

2006 Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med 29 377 387

183. SametJM

1990 The 1990 Report of the Surgeon General: The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation. Am Rev Respir Dis 142 993 994

184. FriedmanHS

TuckerJS

SchwartzJE

Tomlinson-KeaseyC

MartinLR

1995 Psychosocial and behavioral predictors of longevity: The aging and death of the ‘Termites’. Am Psychol 50 69 78

185. TuckerJS

FriedmanHS

WingardDL

SchwartzJE

1996 Marital history at midlife as a predictor of longevity: Alternative explanations to the protective effect of marriage. Health Psychol 15 94 101

186. CoyneJC

RohrbaughMJ

ShohamV

SonnegaJS

NicklasJM

2001 Prognostic importance of marital quality for survival of congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 88 526 529

187. EakerED

SullivanLM

Kelly-HayesM

D'AgostinoRBSr

BenjaminEJ

2007 Marital status, marital strain, and risk of coronary heart disease or total mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Psychosom Med 69 509 513

188. RothmanKJ

GreenlandS

LashTL

2008 Modern Epidemiology Philadelphia Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

189. UchinoBN

CacioppoJT

Kiecolt-GlaserJK

1996 The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull 119 488 531

190. RozanskiA

BlumenthalJA

KaplanJ

1999 Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation 99 2192 2217

191. CohenS

1988 Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychol 7 269 297

192. UchinoBN

Holt-LunstadJ

UnoD

CampoR

ReblinM

2007 The Social Neuroscience of Relationships: An Examination of Health-Relevant Pathways. Social neuroscience: Integrating biological and psychological explanations of social behavior New York, NY, US Guilford Press 474 492

193. UchinoBN

UnoD

Holt-LunstadJ

1999 Social support, physiological processes, and health. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 8 145 148

194. LutgendorfSK

SoodAK

AndersonB

McGinnS

MaiseriH

2005 Social support, psychological distress, and natural killer cell activity in ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 23 7105 7113

195. MiyazakiT

IshikawaT

NakataA

SakuraiT

MikiA

2005 Association between perceived social support and Th1 dominance. Biol Psychol 70 30 37 (2005)

196. MoynihanJA

LarsonMR

TreanorJ

DubersteinPR

PowerA

2004 Psychosocial factors and the response to influenza vaccination in older adults. Psychosom Med 66 950 953

197. CohenS

DoyleWJ

SkonerDP

RabinBS

GwaltneyJMJr

1997 Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA 277 1940 1944

198. Kiecolt-GlaserJK

LovingTJ

StowellJR

MalarkeyWB

LemeshowS

2005 Hostile marital interactions, proinflammatory cytokine production, and wound healing. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62 1377 1384

199. SpiegelD

BloomJR

KraemerH

GottheilE

1989 Psychological support for cancer patients. Lancet 2(8677) 1447

200. AltmanDG