-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Association of Secondhand Smoke Exposure with Pediatric Invasive Bacterial Disease and Bacterial Carriage: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Background:

A number of epidemiologic studies have observed an association between secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure and pediatric invasive bacterial disease (IBD) but the evidence has not been systematically reviewed. We carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of SHS exposure and two outcomes, IBD and pharyngeal carriage of bacteria, for Neisseria meningitidis (N. meningitidis), Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae).Methods and Findings:

Two independent reviewers searched Medline, EMBASE, and selected other databases, and screened articles for inclusion and exclusion criteria. We identified 30 case-control studies on SHS and IBD, and 12 cross-sectional studies on SHS and bacterial carriage. Weighted summary odd ratios (ORs) were calculated for each outcome and for studies with specific design and quality characteristics. Tests for heterogeneity and publication bias were performed. Compared with those unexposed to SHS, summary OR for SHS exposure was 2.02 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.52–2.69) for invasive meningococcal disease, 1.21 (95% CI 0.69–2.14) for invasive pneumococcal disease, and 1.22 (95% CI 0.93–1.62) for invasive Hib disease. For pharyngeal carriage, summary OR was 1.68 (95% CI, 1.19–2.36) for N. meningitidis, 1.66 (95% CI 1.33–2.07) for S. pneumoniae, and 0.96 (95% CI 0.48–1.95) for Hib. The association between SHS exposure and invasive meningococcal and Hib diseases was consistent regardless of outcome definitions, age groups, study designs, and publication year. The effect estimates were larger in studies among children younger than 6 years of age for all three IBDs, and in studies with the more rigorous laboratory-confirmed diagnosis for invasive meningococcal disease (summary OR 3.24; 95% CI 1.72–6.13).Conclusions:

When considered together with evidence from direct smoking and biological mechanisms, our systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that SHS exposure may be associated with invasive meningococcal disease. The epidemiologic evidence is currently insufficient to show an association between SHS and invasive Hib disease or pneumococcal disease. Because the burden of IBD is highest in developing countries where SHS is increasing, there is a need for high-quality studies to confirm these results, and for interventions to reduce exposure of children to SHS.

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 7(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000374

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000374Summary

Background:

A number of epidemiologic studies have observed an association between secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure and pediatric invasive bacterial disease (IBD) but the evidence has not been systematically reviewed. We carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of SHS exposure and two outcomes, IBD and pharyngeal carriage of bacteria, for Neisseria meningitidis (N. meningitidis), Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae).Methods and Findings:

Two independent reviewers searched Medline, EMBASE, and selected other databases, and screened articles for inclusion and exclusion criteria. We identified 30 case-control studies on SHS and IBD, and 12 cross-sectional studies on SHS and bacterial carriage. Weighted summary odd ratios (ORs) were calculated for each outcome and for studies with specific design and quality characteristics. Tests for heterogeneity and publication bias were performed. Compared with those unexposed to SHS, summary OR for SHS exposure was 2.02 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.52–2.69) for invasive meningococcal disease, 1.21 (95% CI 0.69–2.14) for invasive pneumococcal disease, and 1.22 (95% CI 0.93–1.62) for invasive Hib disease. For pharyngeal carriage, summary OR was 1.68 (95% CI, 1.19–2.36) for N. meningitidis, 1.66 (95% CI 1.33–2.07) for S. pneumoniae, and 0.96 (95% CI 0.48–1.95) for Hib. The association between SHS exposure and invasive meningococcal and Hib diseases was consistent regardless of outcome definitions, age groups, study designs, and publication year. The effect estimates were larger in studies among children younger than 6 years of age for all three IBDs, and in studies with the more rigorous laboratory-confirmed diagnosis for invasive meningococcal disease (summary OR 3.24; 95% CI 1.72–6.13).Conclusions:

When considered together with evidence from direct smoking and biological mechanisms, our systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that SHS exposure may be associated with invasive meningococcal disease. The epidemiologic evidence is currently insufficient to show an association between SHS and invasive Hib disease or pneumococcal disease. Because the burden of IBD is highest in developing countries where SHS is increasing, there is a need for high-quality studies to confirm these results, and for interventions to reduce exposure of children to SHS.

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' SummaryIntroduction

Invasive bacterial disease (IBD) is an important cause of child mortality in developing and developed countries [1]–[7], accounting for at least as many child deaths as HIV/AIDS and malaria combined [6]–[8]. The organisms responsible for most pediatric IBD cases are S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), and N. meningitidis [1],[2],[4],[6],[7],[9]. In 2000, there were an estimated 14.5 million cases and 826,000 deaths from pneumococcal disease in children under 5 with estimated incidence ranging from 544 per 100,000 in the Americas to 1,778 per 100,000 in Africa [6]. The burden of Hib was estimated at 8.13 million cases and 371,000 deaths with estimated incidence ranging from 504 per 100,000 in Europe to 3,627 per 100,000 in Africa [7]. While there are currently no analyses of global invasive meningococcal disease burden, regional estimates of incidence range from 0.3 to 4 cases per 100,000 in North America to as high as 1,000 cases per 100,000 in the so-called “meningitis belt” in sub-Saharan Africa [9].

Secondhand smoke (SHS; also referred to as involuntary smoking, passive smoking, or environmental tobacco smoke [ETS]) has been shown to increase the risk of several adverse outcomes in children, including lower respiratory tract infections, middle ear infection, asthma, and sudden infant death syndrome [10],[11]. Since the 1980s, epidemiologic studies have also found an association between SHS exposure and IBD or bacterial carriage, including those related to N. meningitidis, Hib, and S. pneumoniae, which suggests that SHS might be an independent risk factor for IBD. Given the persistent or growing SHS exposure in developing countries, especially in Asia, where IBD poses a major health risk, it is essential to delineate the role of exposure to SHS in the epidemiology of IBD. To our knowledge, no reviews have systematically investigated the quality and consistency of epidemiological evidence on this association, which is an important gap in our understanding of the effect of SHS exposure on the burden of infectious diseases. We carried out a systematic review and quantitative assessment of the association between SHS and the risk of IBD from N. meningitidis, Hib, and S. pneumoniae in pediatric populations, aged 1 mo to 19 y (see below). We also included the effects of SHS exposure on pharyngeal carriage of these three bacteria because asymptomatic carriage is also associated with clinical disease [12]–[16].

Methods

Search Strategy

We carried out a systematic literature search of SHS and IBD using Medline (via PubMed), and EMBASE from 1975 through December 2009. PubMed was searched by combining two separate queries composed of medical subject heading (MeSH) and text word (tw) keywords for the exposure and outcome of interest. The first (exposure) query was searched using the following exploded headings and independent terms: “(cigarette smoke[tw] OR “tobacco smoke pollution”[MeSH] OR “cotinine”[MeSH] OR tobacco smoke[tw] OR passive smoking[tw] OR secondhand smoke[tw] OR second hand smoke[tw] OR parental smoking[tw] OR paternal smoking[tw] OR maternal smoking[tw] OR cotinine[tw]).” The second (outcome) query was searched using exploded headings and independent terms for all three bacterial forms of IBD: (“pneumococcal infections”[MeSH] OR “Streptococcus pneumoniae”[MeSH] OR “Haemophilus influenzae”[MeSH] OR “Neisseria meningitidis”[MeSH] OR “Sepsis”[MeSH] OR “Meningitis, Meningococcal”[MeSH] OR “Haemophilus Infections”[MeSH] OR meningococcemia[tw] OR meningococcal[tw] OR pneumococcal[tw] OR Haemophilus influenzae[tw] OR h influenzae[tw] OR h influenza[tw] OR Neisseria meningitidis[tw]).”

We used manual restriction by age and study type (versus using automated methods in PubMed) to avoid unnecessarily eliminating any articles relevant to the search. A similar search strategy and search terms were used in EMBASE. The searches and studies included were not limited by publication date, country, or language. PubMed and EMBASE searches were conducted independently by two authors (C-CL and NAM). To ensure comprehensive acquisition of literature, independent supplemental manual searches were performed on the reference lists of relevant articles and other minor databases, including Web of Science, Cochrane databases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Smoking and Health Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructures (CNKI), Latin American and Caribbean of Health Sciences Information System (LILACS), and African Index Medicus (AIM). Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) and EMbase TREE tool (EMTREE) were used to guide the choice of appropriate search terms in other databases.

Inclusion and Exclusion

Two reviewers independently identified articles eligible for in-depth examination using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were included if at least one of the following outcomes was analyzed: invasive S. pneumoniae disease, invasive Hib disease, invasive N. meningitidis disease, and naso - or oropharyngeal carriage of any of the above three bacteria. IBD was defined as bacterial meningitis, bacterial epiglottitis, bacteremia, or microbiologically documented infection at other normally sterile sites with relevant clinical syndrome. Relevant exposures were defined as SHS or ETS exposure, parental smoking, household smoking or presence of household smoker(s), and regular contact with smokers. We excluded studies in which active smoking was the only exposure, active smoking was not distinguished from passive smoking, or studies that also included prenatal exposure. Study types included were cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional surveys, whereas case reports, review articles, editorials, and clinical guidelines were excluded. We included studies on human participants aged 1 mo to 19 y, i.e. infants, children, and adolescents. We excluded the neonatal period because of its established epidemiologic and pathophysiologic distinction from the post-neonatal period [17]. We included adolescents because age-specific N. meningitidis incidence peaks in childhood as well as adolescence; while S. pneumoniae incidence peaks in childhood and infancy, this disease may also occur in adolescents [4],[6],[9].

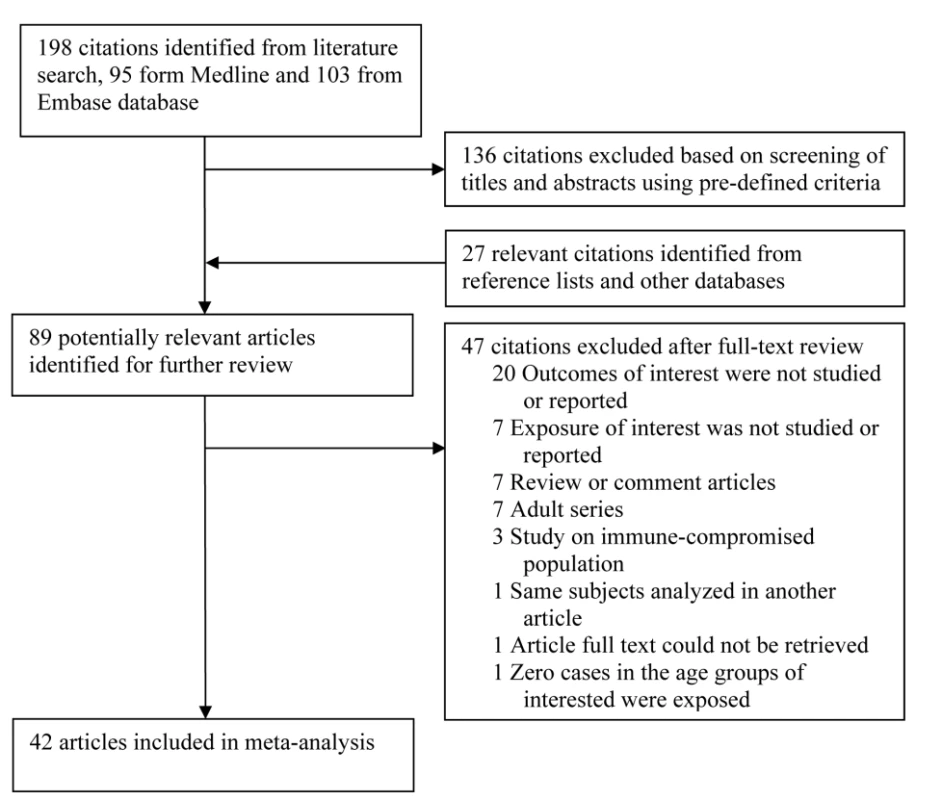

Studies on immunocompromised populations were excluded. When multiple articles reported on the same study population, we included only the most detailed publication that met the inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies on articles meriting inclusion between reviewers were resolved by a consensus meeting of three authors (C-CL, NAM, and ME). Study selection is summarized in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of study identification and inclusion.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were extracted on study location, setting (e.g., community, school, hospital, etc.), population characteristics including age range and sex ratio, number of participants, definition of exposure and diagnosis of outcome, crude and adjusted effect sizes as available, and confidence intervals (CIs). We also recorded quality indicators of study design including presence of appropriate controls and covariates used for adjustment in multivariate analysis. We conducted separate analyses on IBD and bacterial carriage. When studies were identified as containing pertinent data not included in the published article (e.g., when they did not differentiate between pediatric and adult participants), we contacted the authors to obtain the missing data. When a response was not provided and raw data were provided in the article, we manually calculated the unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Otherwise, such articles were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

We followed the PRISMA guidelines for meta-analysis of observational studies in our data extraction, analysis, and reporting (Text S1) [18]. Heterogeneity was tested using the Cochran Q statistic (p<0.05) and quantified with the I2 statistic, which describes the variation of effect size that is attributable to heterogeneity across studies [19],[20]. The value of the I2 statistic was used to select the appropriate pooling method: fixed-effects models were used for I2<50% and random-effects models for I2 ≥50% [19],[20]. CIs of I2 were calculated by the methods suggested by Higgins et al. [21]. Pooled ORs were summarized with Mantel–Haenszel method for fixed-effect models and DerSimonian and Laird method for random effect models [20]. Galbraith plots were used to visualize the impact of individual studies on the overall homogeneity test statistic [22]. Meta-regression was used to evaluate whether effect size estimates were significantly different by specific study characteristics and quality factors, particularly those of adjustment for covariates and whether IBD diagnosis was only the more rigorous laboratory-confirmed or a mix of clinical-only and laboratory-confirmed diagnosis. We defined a study as having laboratory-confirmed diagnosis as the primary outcome if the study had more than 80% of cases confirmed by a positive culture, rapid antigen test, or PCR-based identification. In addition to meta-regression, we reestimated effects size stratified on the same study characteristics and quality factors, so that they are available as separate estimates. Even when the meta-regression result was not statistically significant, we conducted a subgroup analysis when a study characteristic was clinically or epidemiologically relevant, e.g., the age range of study participants.

The presence and the effect of publication bias was examined using a combination of the Begg and Egger tests and the “trim and fill” procedure [19],[23],[24]. This procedure considers the hypothetical possibility of studies that were missed, imputes their ORs, and recalculates a pooled OR that incorporates these hypothetical missing studies [23]. Trim-and-fill ORs are reported when the tests for publication bias were significant.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 10.1 (StataCorp). The metan, metabias, galbr, metareg, and metatrim macros were used for meta-analytic procedures. p-Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Search Results and Study Characteristics

Our search identified a total of 198 studies, of which 95 were from PubMed and 103 from EMBASE. Screening based on title and abstract identified 62 citations for full-text review (Figure 1). An additional 27 studies were identified from reference lists of the identified articles and from other databases. Of the 89 potentially relevant articles, 47 were excluded for reasons in Figure 1, leaving a total of 42 studies that met the inclusion criteria.

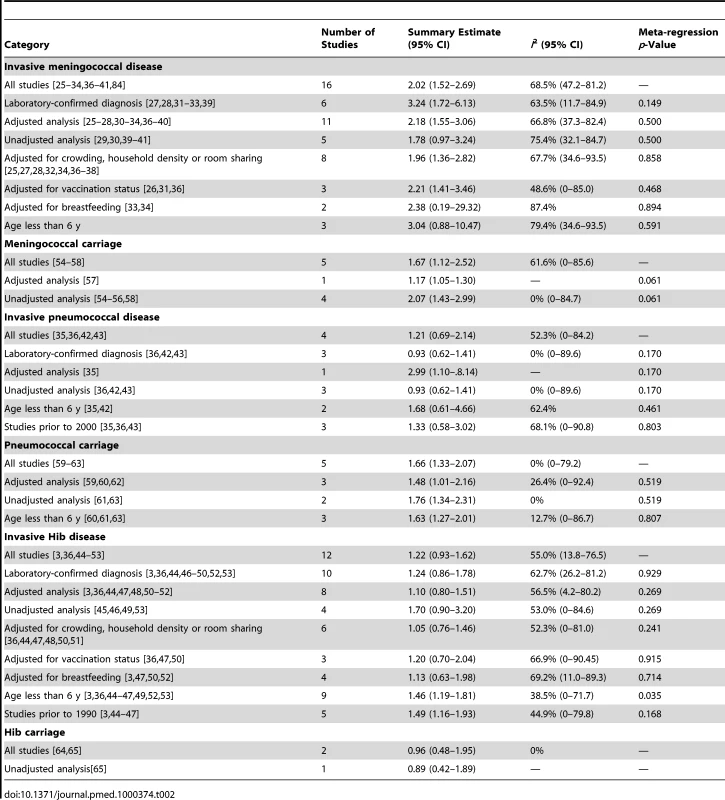

There were 30 studies on invasive disease and 12 on pharyngeal carriage. All invasive disease studies utilized a case-control design and all carriage studies were cross-sectional studies. The studies varied in their SHS exposure metric, age range, and case definition (Table 1). Household smoking or the presence of household smokers was the most frequent measure of SHS exposure (26 of 42 studies), while most others used maternal, paternal, or caregiver smoking. Nineteen of 30 invasive disease studies used laboratory-confirmed diagnosis as the case definition for all participants, while others had individuals with a combination of clinical-only and laboratory-confirmed diagnosis. Where clinical diagnoses were included, they were specific to the organism, including hemorrhagic rash for invasive meningococcal disease and epiglottitis for invasive Hib disease. The inclusion of carefully clinically defined cases has the potential to reduce bias in settings where pre-referral antibiotic treatment is common, either by policy or because of wide availability of antibiotics in the community. All 12 bacterial carriage studies used a culture definition, eight from nasopharyngeal swabs and the remainder from oropharyngeal swabs. The studies also varied in covariates adjusted for as shown in Table 1.

Tab. 1. Summary of studies of the association between SHS exposure and IBD or pharyngeal bacterial carriage.

Individual studies have used different phrasing of exposure metrics. We have used “household smoking” in all cases where the definition was equivalent to smoking by household members or smoking at home. SHS Exposure and IBD

Invasive meningococcal disease

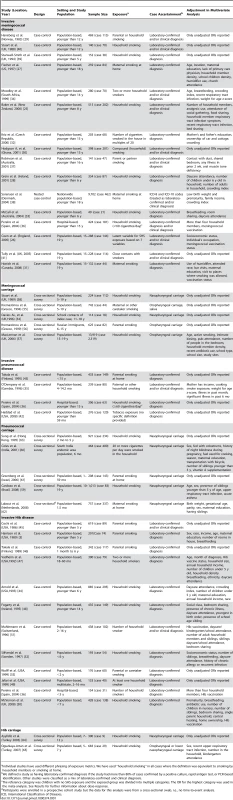

The 16 studies with invasive meningococcal disease as the primary outcome included a total of 1,948 cases and 13,734 controls (Table 1) [25]–[41]. When the results from all studies were combined, SHS exposure was associated with an increased risk of invasive meningococcal disease (pooled OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.52–2.69; test of heterogeneity p<0.001, I2 = 68.5%) (Figure 2A). Galbraith plots showed that two studies from Australia and Ghana were potential sources of heterogeneity [30],[37]. The effect estimate excluding these two studies was slightly reduced compared with the overall effect estimate (OR 1.79, 95% CI 1.56–2.05).

Fig. 2. ORs for invasive bacterial disease for exposure to secondhand smoke compared to nonexposure: (A) meningococcal disease, (B) pneumococcal disease, (C) Hib disease.

Meta-regression analysis did not show any significant effect size modification by the specific study characteristics considered, possibly because of a relatively small number of studies (Table 2). In subgroup analyses, the association was larger in studies that used laboratory-confirmed cases (OR 3.24, 95% CI 1.72–6.13) [27],[28],[31]–[33],[39]. Subgroup analysis of studies with different covariate adjustment generally found similar magnitude and direction of ORs compared with the overall effect size (Table 2) [25]–[28],[30]–[34],[36]–[40]. When the analysis was restricted to the three studies on preschool children (age ≤6 y), the association was stronger but nonsignificant (OR 3.04, 95% CI 0.89–10.47) [28],[33],[39].

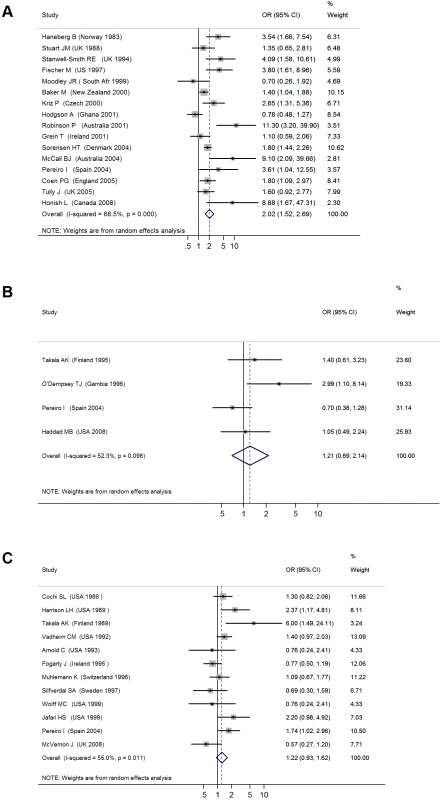

Tab. 2. Summary of subgroup analysis of studies of the association of SHS and IBD or pharyngeal bacterial carriage.

Invasive pneumococcal disease

The four case-control studies on SHS exposure and invasive pneumococcal disease included a total of 412 cases and 842 controls (Table 1) [35],[36],[42],[43]. Combined results from all studies yielded a nonsignificant association (pooled OR 1.21, 95% CI 0.69–2.14; test of heterogeneity p = 0.098, I2 = 52.3%) (Figure 2B). Once again, meta-regression did not show any significant effect size modification by specific study characteristics considered (Table 2). In the case of adjustment, there was only one adjusted study that had a large but imprecise effect estimate (OR 2.99, 95% CI 1.10–8.14) [35]. In subgroup analysis, the three studies with laboratory-confirmed diagnosis had a null effect size of 0.93 (95% CI 0.62–1.41). The association was stronger in studies on preschool children, but remained nonsignificant (OR 1.68, 95% CI 0.61–4.66) (Table 2) [35],[42]. Studies before 2000, when pneumococcal vaccines (including the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine) were not widely available, also showed a stronger but nonsignificant association (OR 1.33, 95% CI 0.58–3.02) (Table 2) [3],[44]–[47].

Invasive Hib disease

The 12 case-control studies on SHS exposure and invasive Hib disease included a total of 1,228 cases and 3,076 controls (Table 1) [3],[36],[44]–[53]. The overall effect size was positive but nonsignificant (pooled OR 1.22, 95% CI 0.93–1.62; test of heterogeneity p = 0.011, I2 = 55.0%) (Figure 2C). Excluding a study in Finland that was a potential source of heterogeneity led to a lower pooled effect size, which remained nonsignificant (OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.99–1.41) [46]. Of study characteristics assessed in meta-regression, only being among preschool children was statistically significant (Table 2). In subgroup analysis, studies with laboratory-confirmed diagnosis had a similar effect size of 1.24 (95% CI 0.86–1.78), whereas adjusted studies yielded a lower and nonsignificant effect size (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.80–1.51) [3],[36],[44],[46]–[53]. Studies on preschool children had a significant positive association (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.19–1.81) (Table 2) [3],[36],[44]–[47],[49],[52],[53]. Studies before 1990, when Hib vaccine was not yet commonly available, had a stronger positive association (OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.16–1.93) than the overall analysis [3],[44]–[47].

SHS Exposure and Pharyngeal Bacterial Carriage

N. meningitidis carriage

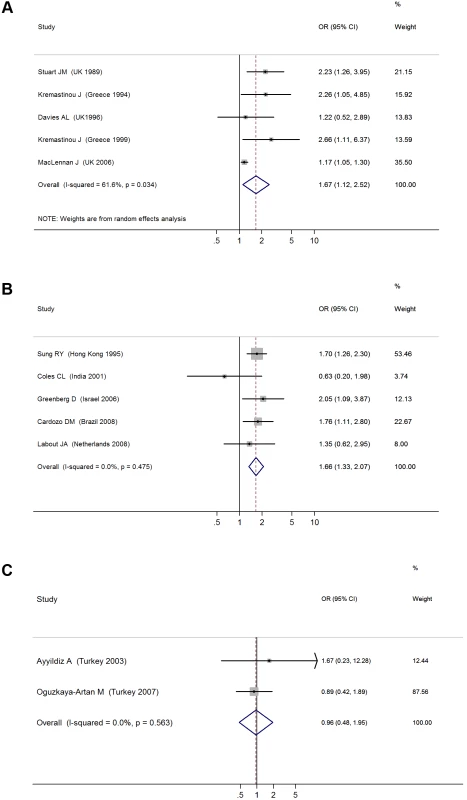

We identified a total of five cross-sectional surveys on pharyngeal carriage of N. meningitidis comprising 2,575 carriers and 15,624 noncarriers (Table 1) [54]–[58]. The pooled OR for all studies showed a significant positive association between SHS exposure and pharyngeal N. meningitidis carriage (pooled OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.12–2.52; test of heterogeneity p = 0.034, I2 = 61.6%) [54]–[58] (Figure 3A). Studies with multivariate adjustment had an OR smaller than the overall analysis, but their pooled effect size remained significant (1.17 [1.05–1.30]) (Table 2) [57]. However, meta-regression analysis indicated that the difference between adjusted and crude effect sizes had borderline statistical significance (p = 0.061).

Fig. 3. ORs for pharyngeal carriage of bacteria for exposure to secondhand smoke compared to nonexposure: (A) <i>N. meningitidis</i>, (B) <i>S. pneumonia</i>, (C) Hib.

S. pneumoniae carriage

There were five cross-sectional surveys on SHS exposure and pharyngeal carriage of S. pneumoniae with a total of 860 carriers and 1,746 noncarriers (Table 1) [59]–[63]. The pooled result from all studies showed a significant positive association (pooled OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.33–2.07; test of heterogeneity p = 0.48, I2 = 0%) (Figure 3B). Adjustment or study characteristics did not significantly modify the effect size in meta-regression analysis (Table 2). Subgroup analysis on the three studies with multivariate adjustment yielded a similar association with borderline significance (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.01–2.16) [59],[60],[62]. Studies on preschool children also had a significant association of similar magnitude (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.27–2.10) (Table 2) [60],[61],[63].

Hib carriage

There were only two cross-sectional studies on SHS exposure and childhood pharyngeal carriage of Hib that included a total of 38 cases and 945 controls (Table 1) [64],[65]. The pooled association was nonsignificant (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.48–1.95; test of heterogeneity p = 0.56, I2 = 0%) (Figure 3C). The study population did not include the most vulnerable age group, i.e., preschool children.

Dose-Response Relationships

Dose-response relationships were examined in four invasive meningococcal disease studies [28],[32],[36],[39], three invasive Hib disease studies [47],[50],[51], and one invasive pneumococcal disease study [36]. The studies had used different metrics to measure exposure and dose including number of cigarettes smoked per day and number of household smokers. The absence of a consistent definition of exposure meant that a pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship was not possible. Broadly, with the exception of the pneumococcal study and one Hib study, there was a dose-response relationship with the number of cigarettes smoked per day or the number of smokers in the household [28],[32],[36],[39],[47],[50],[51].

Publication Bias

The test for publication bias was significant in three of the six outcomes, namely invasive meningococcal and pneumococcal diseases and N. meningitidis carriage (Table 3). The trim-and-fill ORs for meningococcal disease and N. meningitidis carriage were lower but the former remained statistically significant. The positive, but nonsignificant, OR of 1.21 (95% CI 0.69–2.14) for pneumococcal disease was replaced by a trim-and-fill OR of 0.83 (95% CI 0.45–1.53).

Tab. 3. Tests for publication bias and trim-and-fill ORs.

Trim-and-fill ORs were calculated when publication bias tests were statistically significant. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the association between SHS exposure and IBD or pharyngeal carriage of pathogenic bacteria in pediatric populations revealed a consistent and positive association between SHS exposure and invasive meningococcal disease and pharyngeal carriage of N. meningitidis, as well as a positive association with S. pneumoniae carriage. There was also a positive but not statistically significant association with invasive pneumococcal and Hib diseases. The association with Hib carriage was based on only two studies and was null. When subanalyses could be conducted, the pooled effect sizes with and without adjustment for important risk factors were generally similar, becoming slightly smaller for meningococcal and pneumococcal carriage and for invasive Hib disease, and larger for invasive meningococcal and pneumococcal diseases. Studies with laboratory-confirmed diagnosis, the more rigorous outcome, had large and statistically significant effect sizes for meningococcal disease but not for pneumococcal and Hib diseases.

The nonsignificant associations with invasive pneumococcal disease may have been partially due to the relatively small pooled sample sizes (412 cases), whereas that of Hib disease is less likely to be due to sample size (1,228 cases). For Hib disease, studies on the most vulnerable ages (≤6 y old) had larger and significant effect estimates. A factor that may have contributed to the insignificant effects may be the increasing use of Hib vaccine (since 1990) and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (since 2000). Studies before the vaccine era had larger effect sizes for both Hib and pneumococcal diseases, but these were only statistically significant for Hib. These factors, and the strong association that has been observed between active smoking and invasive pneumococcal disease [66], should motivate additional high-quality studies with large sample sizes to clarify the role of SHS in the etiology of invasive pneumococcal disease.

There are plausible mechanisms for the effects of SHS on bacterial diseases. Both in vivo and in vitro experimental studies have found that SHS exposure may induce structural changes in the respiratory tract including peribronchiolar inflammation and fibrosis, increased mucosal permeability, and impairment of the mucociliary clearance [67],[68]. It may also decrease immune defenses, e.g., a decreased level and depressed responses of circulating immunoglobulins, decreased CD4+ lymphocyte counts and increased CD8+ lymphocyte counts, depressed phagocyte activity, and decreased release of proinflammatory cytokines [68]–[72]. All these mechanisms might increase the risk of bacterial invasion and subsequent infection. The significant findings here regarding the association of SHS exposure with bacterial carriage also support a plausible etiological role for SHS in invasive bacterial disease, because asymptomatic carriage is an intermediate step towards invasive disease [12],[13],[15],[16]. Asymptomatic carriage itself has a public health implication because it is important in population transmission of infectious bacteria[12],[15].

Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review has strengths and limitations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence on the association between SHS exposure and pediatric IBD. We were able to include clinical invasive disease as well as the etiologically and epidemiologically important intermediate stage of asymptomatic bacterial carriage. As far as possible, we assessed sensitivity to important methodological design and quality characteristics using meta-regression and subgroup analysis. Our search covered multiple databases without language limitation.

A key limitation of our study was the relatively small number of studies, specifically from developing countries in which the IBD burden is the largest, smoking is increasing, and vaccination coverage may be lower. Notably, two African studies had a nonsignificant effect size for invasive meningococcal disease [30],[34]. One of these studies was from northern Ghana, where more than 93% of participants were exposed to fuelwood smoke [30]. In addition, negative residual confounding (due to the potential negative association of household smoking with economic status) cannot be ruled out as a source of the nonsignificant negative finding. The second study, from urban South Africa, had included an interaction term between recent upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and SHS exposure in the multivariate analysis, which had an OR of 3.6 (95% CI 1.4–7.3) [34]. If recent URTI itself was caused by SHS and can increase the risk of IBD, then this adjustment would attenuate the true effect of the SHS term. A third African study from The Gambia had an OR of 2.99 (95% CI 1.10–8.14) for pneumococcal disease [35]. The limited number of studies from developing countries makes it difficult to assess the role of factors such as background incidence rate, nutritional status, vaccination, and coexposure to wood smoke on the ORs for SHS-IBD association. A second potential limitation is that both the exposure and outcome measurements may have been subject to error, which is likely to have biased our results towards the null and reduced its significance. Third, heterogeneity of effect sizes across studies restricts our ability and confidence to generalize the results of this pooled data analysis to all populations. Fourth, the studies on association with bacterial carriage were distinct from those on IBD and no SHS-IBD studies had assessed carriage at baseline. As a result, we were not able to assess whether SHS exposure only increases the risk for colonization, or increases the risk of subsequent infection, or both. Fifth, because IBD is a complex disease with multiple causes, there is potential for residual confounding in the observational studies included in our analysis. This is especially relevant given that the currently available SHS-IBD studies were case-control or nested case-control studies and those on SHS-bacterial carriage were cross-sectional studies. Our findings on the potential causal associations should motivate new prospective studies. Sixth, our study focused on pediatric SHS exposure and did not assess studies on perinatal SHS exposure as a risk factor for IBD, with some of the effect possibly mediated through low birth weight. [73],[74]. Finally, while we assessed the potential for publication bias and report trim-and-fill ORs, the latter estimates are themselves subject to methodologic limitations especially when the number of studies is small [75].

Despite the limitations of current epidemiologic studies, our meta-analysis provides some evidence of an association between SHS and IBD and pharyngeal carriage, especially in preschool children. Although there are efficacious vaccines against all three pathogens assessed in this study, many children in low-income countries are not covered in routine immunizations and have limited access to case management [76]–[80]. Vaccine pricing remains an obstacle to uptake, while waning immunity and serotype replacement may undermine long-term vaccine effectiveness [78],[81]–[83]. Thus scaling up vaccine coverage and case management must be accompanied by nonvaccine interventions, such as environmental interventions, to address the large burden of IBDs. Tobacco smoking and SHS exposure have increased in low-income and middle-income countries, making SHS exposure a global problem [84],[85]. While public smoking bans have been effective in reducing adult SHS exposure and adverse health effects [86],[87], children's exposure to SHS may occur at home, where bans may be difficult to enforce [11]. An estimated 700 million children worldwide are exposed to SHS at home [84]. If the observed effects are causal, our results indicate that in a population where 25% of young children are exposed to SHS (e.g., Brazil or South Africa), 5%–20% of IBD cases may be attributable to this risk factor; the attributable fraction would be 10%–34% in populations where exposure is 50% (e.g., Egypt or Indonesia). Effects of such magnitude should motivate a number of research and intervention steps specifically related to SHS and pediatric IBD: Firstly, there should be well-designed prospective studies with high-quality measurement of exposure, outcome, and potential confounders to overcome the limitations of the current studies. Secondly, interventions that specifically focus on reducing children's exposure at home, schools, and other environments should be pursued. These two directions are particularly important in developing countries where the IBD burden is high and exposure to SHS is high or increasing. Finally, the effects of other combustion pollutant sources that are common in developing countries, especially smoke from wood and animal dung fuels, on IBD should be subject to research.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BerkleyJA

LoweBS

MwangiI

WilliamsT

BauniE

2005

Bacteremia among children admitted to a rural hospital in Kenya.

N Engl J Med

352

39

47

2. BrentAJ

AhmedI

NdirituM

LewaP

NgetsaC

2006

Incidence of clinically significant bacteraemia in children who present to hospital in Kenya: community-based observational study.

Lancet

367

482

488

3. HarrisonLH

BroomeCV

HightowerAW

1989

Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide vaccine: an efficacy study. Haemophilus Vaccine Efficacy Study Group.

Pediatrics

84

255

261

4. KaijalainenT

KharitSM

KvetnayaAS

SirkiaK

HervaE

2008

Invasive infections caused by Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae among children in St Petersburg, Russia.

Clin Microbiol Infect

14

507

510

5. MulhollandEK

AdegbolaRA

2005

Bacterial infections–a major cause of death among children in Africa.

N Engl J Med

352

75

77

6. O'BrienKL

WolfsonLJ

WattJP

HenkleE

Deloria-KnollM

2009

Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates.

Lancet

374

893

902

7. WattJP

WolfsonLJ

O'BrienKL

HenkleE

Deloria-KnollM

2009

Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5 years: global estimates.

Lancet

374

903

911

8. World Health Organization

2005

Make every mother and child count.

Geneva

World Health Organization

9. HarrisonLH

TrotterCL

RamsayME

2009

Global epidemiology of meningococcal disease.

Vaccine

27

Suppl 2

B51

63

10. California Environmental Protection Agency

2005

Proposed Identification of Environmental Tobacco Smoke as a TAC; Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment CEPA, editor.

Sacramento

California Environmental Protection Agency

11. Office of the Surgeon General

2006

The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General; Department of Health and Human Services C, editor.

Atlanta (Georgia)

Office of the Surgeon General

12. BogaertD

De GrootR

HermansPW

2004

Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization: the key to pneumococcal disease.

Lancet Infect Dis

4

144

154

13. GrayBM

ConverseGMIII

DillonHCJr

1980

Epidemiologic studies of Streptococcus pneumoniae in infants: acquisition, carriage, and infection during the first 24 months of life.

J Infect Dis

142

923

933

14. Lloyd-EvansN

O'DempseyTJ

BaldehI

SeckaO

DembaE

1996

Nasopharyngeal carriage of pneumococci in Gambian children and in their families.

Pediatr Infect Dis J

15

866

871

15. van der PollT

OpalSM

2009

Pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia.

Lancet

374

1543

1556

16. van DeurenM

BrandtzaegP

van der MeerJW

2000

Update on meningococcal disease with emphasis on pathogenesis and clinical management.

Clin Microbiol Rev

13

144

166, table of contents

17. VergnanoS

SharlandM

KazembeP

MwansamboC

HeathPT

2005

Neonatal sepsis: an international perspective.

Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed

90

F220

F224

18. MoherD

LiberatiA

TetzlaffJ

AltmanDG

2009

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement.

Ann Intern Med

151

264

269, W264

19. HigginsJP

ThompsonSG

DeeksJJ

AltmanDG

2003

Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses.

BMJ

327

557

560

20. DerSimonianR

LairdN

1986

Meta-analysis in clinical trials.

Control Clin Trials

7

177

188

21. HigginsJP

ThompsonSG

2002

Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis.

Stat Med

21

1539

1558

22. GalbraithRF

1988

A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials.

Stat Med

7

889

894

23. DuvalS

TweedieR

2000

Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis.

Biometrics

56

455

463

24. EggerM

Davey SmithG

SchneiderM

MinderC

1997

Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test.

BMJ

315

629

634

25. BakerM

McNicholasA

GarrettN

JonesN

StewartJ

2000

Household crowding a major risk factor for epidemic meningococcal disease in Auckland children.

Pediatr Infect Dis J

19

983

990

26. CoenPG

TullyJ

StuartJM

AshbyD

VinerRM

2006

Is it exposure to cigarette smoke or to smokers which increases the risk of meningococcal disease in teenagers?

Int J Epidemiol

35

330

336

27. FischerM

HedbergK

CardosiP

PlikaytisBD

HoeslyFC

1997

Tobacco smoke as a risk factor for meningococcal disease.

Pediatr Infect Dis J

16

979

983

28. GreinT

O'FlanaganD

2001

Day-care and meningococcal disease in young children.

Epidemiol Infect

127

435

441

29. HanebergB

TonjumT

RodahlK

Gedde-DahlTW

1983

Factors preceding the onset of meningococcal disease, with special emphasis on passive smoking, symptoms of ill health.

NIPH Ann

6

169

173

30. HodgsonA

SmithT

GagneuxS

AdjuikM

PluschkeG

2001

Risk factors for meningococcal meningitis in northern Ghana.

Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg

95

477

480

31. HonishL

SoskolneCL

SenthilselvanA

HoustonS

2008

Modifiable risk factors for invasive meningococcal disease during an Edmonton, Alberta outbreak, 1999-2002.

Can J Public Health

99

46

51

32. KrizP

BobakM

KrizB

2000

Parental smoking, socioeconomic factors, and risk of invasive meningococcal disease in children: a population based case-control study.

Arch Dis Child

83

117

121

33. McCallBJ

NeillAS

YoungMM

2004

Risk factors for invasive meningococcal disease in southern Queensland, 2000-2001.

Intern Med J

34

464

468

34. MoodleyJR

CoetzeeN

HusseyG

1999

Risk factors for meningococcal disease in Cape Town.

S Afr Med J

89

56

59

35. O'DempseyTJ

McArdleTF

MorrisJ

Lloyd-EvansN

BaldehI

1996

A study of risk factors for pneumococcal disease among children in a rural area of west Africa.

Int J Epidemiol

25

885

893

36. PereiroI

Diez-DomingoJ

SegarraL

BallesterA

AlbertA

2004

Risk factors for invasive disease among children in Spain.

J Infect

48

320

329

37. RobinsonP

TaylorK

NolanT

2001

Risk-factors for meningococcal disease in Victoria, Australia, in 1997.

Epidemiol Infect

127

261

268

38. SørensenHT

LabouriauR

JensenES

MortensenPB

SchønheyderHC

2004

Fetal growth, maternal prenatal smoking, and risk of invasive meningococcal disease: a nationwide case-control study.

Int J Epidemiol

33

816

820

39. Stanwell-SmithRE

StuartJM

HughesAO

RobinsonP

GriffinMB

1994

Smoking, the environment and meningococcal disease: a case control study.

Epidemiol Infect

112

315

328

40. StuartJM

CartwrightKA

DawsonJA

RickardJ

NoahND

1988

Risk factors for meningococcal disease: a case control study in south west England.

Community Med

10

139

146

41. TullyJ

VinerRM

CoenPG

StuartJM

ZambonM

2006

Risk and protective factors for meningococcal disease in adolescents: matched cohort study.

BMJ

445

450

42. HaddadMB

PorucznikCA

JoyceKE

DeAK

PaviaAT

2008

Risk factors for pediatric invasive pneumococcal disease in the Intermountain West, 1996-2002.

Ann Epidemiol

18

139

146

43. TakalaAK

JeroJ

KelaE

RonnbergPR

KoskenniemiE

1995

Risk factors for primary invasive pneumococcal disease among children in Finland.

JAMA

273

859

864

44. ArnoldC

MakintubeS

IstreGR

1993

Day care attendance and other risk factors for invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b disease.

Am J Epidemiol

138

333

340

45. CochiSL

FlemingDW

HightowerAW

LimpakarnjanaratK

FacklamRR

1986

Primary invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b disease: a population-based assessment of risk factors.

J Pediatr

108

887

896

46. TakalaAK

EskolaJ

PalmgrenJ

RonnbergPR

KelaE

1989

Risk factors of invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b disease among children in Finland.

J Pediatr

115

694

701

47. VadheimCM

GreenbergDP

BordenaveN

ZiontzL

ChristensonP

1992

Risk factors for invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b in Los Angeles County children 18-60 months of age.

Am J Epidemiol

136

221

235

48. FogartyJ

MoloneyAC

NewellJB

1995

The epidemiology of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in the Republic of Ireland.

Epidemiol Infect

114

451

463

49. JafariHS

AdamsWG

RobinsonKA

PlikaytisBD

WengerJD

1999

Efficacy of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines and persistence of disease in disadvantaged populations. The Haemophilus Influenzae Study Group.

Am J Public Health

89

364

368

50. McVernonJ

AndrewsN

SlackM

MoxonR

RamsayM

2008

Host and environmental factors associated with Hib in England, 1998-2002.

Arch Dis Child

93

670

675

51. MuhlemannK

AlexanderER

WeissNS

PepeM

SchopferK

1996

Risk factors for invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease among children 2-16 years of age in the vaccine era, Switzerland 1991-1993. The Swiss H. Influenzae Study Group.

Int J Epidemiol

25

1280

1285

52. SilfverdalSA

BodinL

HugossonS

GarpenholtO

WernerB

1997

Protective effect of breastfeeding on invasive Haemophilus influenzae infection: a case-control study in Swedish preschool children.

Int J Epidemiol

26

443

450

53. WolffMC

MoultonLH

NewcomerW

ReidR

SantoshamM

1999

A case-control study of risk factors for Haemophilus influenzae type B disease in Navajo children.

Am J Trop Med Hyg

60

263

266

54. DaviesAL

O'FlanaganD

SalmonRL

ColemanTJ

1996

Risk factors for Neisseria meningitidis carriage in a school during a community outbreak of meningococcal infection.

Epidemiol Infect

117

259

266

55. KremastinouJ

BlackwellC

TzanakakiG

KallergiC

EltonR

1994

Parental smoking and carriage of Neisseria meningitidis among Greek schoolchildren.

Scand J Infect Dis

26

719

723

56. KremastinouJ

TzanakakiG

VelonakisE

VoyiatziA

NickolaouA

1999

Carriage of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria lactamica among ethnic Greek school children from Russian immigrant families in Athens.

FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol

23

13

20

57. MacLennanJ

KafatosG

NealK

AndrewsN

CameronJC

2006

Social behavior and meningococcal carriage in British teenagers.

Emerg Infect Dis

12

950

957

58. StuartJM

CartwrightKA

RobinsonPM

NoahND

1989

Effect of smoking on meningococcal carriage.

Lancet

2

723

725

59. CardozoDM

Nascimento-CarvalhoCM

AndradeAL

Silvany-NetoAM

DaltroCH

2008

Prevalence and risk factors for nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae among adolescents.

J Med Microbiol

57

185

189

60. ColesCL

KanungoR

RahmathullahL

ThulasirajRD

KatzJ

2001

Pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization in young South Indian infants.

Pediatr Infect Dis J

20

289

295

61. GreenbergD

Givon-LaviN

BroidesA

BlancovichI

PeledN

2006

The contribution of smoking and exposure to tobacco smoke to Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae carriage in children and their mothers.

Clin Infect Dis

42

897

903

62. LaboutJA

DuijtsL

ArendsLR

JaddoeVW

HofmanA

2008

Factors associated with pneumococcal carriage in healthy Dutch infants: the generation R study.

J Pediatr

153

771

776

63. SungRY

LingJM

FungSM

OppenheimerSJ

CrookDW

1995

Carriage of Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae in healthy Chinese and Vietnamese children in Hong Kong.

Acta Paediatr

84

1262

1267

64. AyyildizA

AktasAE

YazgiH

2003

Nasopharyngeal carriage rate of Haemophilus influenzae in children aged 7-12 years in Turkey.

Int J Clin Pract

57

686

688

65. Oguzkaya-ArtanM

BaykanZ

ArtanC

2008

Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in healthy preschool children.

Jpn J Infect Dis

61

70

72

66. NuortiJP

ButlerJC

FarleyMM

HarrisonLH

McGeerA

2000

Cigarette smoking and invasive pneumococcal disease. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team.

N Engl J Med

342

681

689

67. DyeJA

AdlerKB

1994

Effects of cigarette smoke on epithelial cells of the respiratory tract.

Thorax

49

825

834

68. WannerA

SalathéM

O'RiordanTG

1996

Mucociliary clearance in the airways.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

154

1868

1902

69. ArcaviL

BenowitzNL

2004

Cigarette smoking and infection.

Arch Intern Med

164

2206

2216

70. GaschlerGJ

ZavitzCC

BauerCM

SkrticM

LindahlM

2008

Cigarette smoke exposure attenuates cytokine production by mouse alveolar macrophages.

Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol

38

218

226

71. GreenRM

GallyF

KeeneyJG

AlperS

GaoB

2009

Impact of cigarette smoke exposure on innate immunity: a Caenorhabditis elegans model.

PLoS One

4

e6860

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006860

72. Martí-LliterasP

RegueiroV

MoreyP

HoodDW

SausC

2009

Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae clearance by alveolar macrophages is impaired by exposure to cigarette smoke.

Infect Immun

77

4232

4242

73. SorensenHT

LabouriauR

JensenES

MortensenPB

SchonheyderHC

2004

Fetal growth, maternal prenatal smoking, and risk of invasive meningococcal disease: a nationwide case-control study.

Int J Epidemiol

33

816

820

74. YusufHR

RochatRW

BaughmanWS

GargiulloPM

PerkinsBA

1999

Maternal cigarette smoking and invasive meningococcal disease: a cohort study among young children in metropolitan Atlanta, 1989-1996.

Am J Public Health

89

712

717

75. MorenoSG

SuttonAJ

TurnerEH

AbramsKR

CooperNJ

2009

Novel methods to deal with publication biases: secondary analysis of antidepressant trials in the FDA trial registry database and related journal publications.

BMJ

339

b2981

76. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

2005

Direct and indirect effects of routine vaccination of children with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease–United States, 1998-2003.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep

54

893

897

77. De WalsP

DeceuninckG

BoulianneN

De SerresG

2004

Effectiveness of a mass immunization campaign using serogroup C meningococcal conjugate vaccine.

JAMA

292

2491

2494

78. LevineOS

O'BrienKL

KnollM

AdegbolaRA

BlackS

2006

Pneumococcal vaccination in developing countries.

Lancet

367

1880

1882

79. LimSS

SteinDB

CharrowA

MurrayCJ

2008

Tracking progress towards universal childhood immunisation and the impact of global initiatives: a systematic analysis of three-dose diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis immunisation coverage.

Lancet

372

2031

2046

80. MorrisSK

MossWJ

HalseyN

2008

Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine use and effectiveness.

Lancet Infect Dis

8

435

443

81. MadhiSA

AdrianP

KuwandaL

CutlandC

AlbrichWC

2007

Long-term effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae–and associated interactions with Staphylococcus aureus and Haemophilus influenzae colonization–in HIV-Infected and HIV-uninfected children.

J Infect Dis

196

1662

1666

82. MadhiSA

AdrianP

KuwandaL

JassatW

JonesS

2007

Long-term immunogenicity and efficacy of a 9-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine in human immunodeficient virus infected and non-infected children in the absence of a booster dose of vaccine.

Vaccine

25

2451

2457

83. ObaroSK

AdegbolaRA

BanyaWA

GreenwoodBM

1996

Carriage of pneumococci after pneumococcal vaccination.

Lancet

348

271

272

84. World Health Organization

2009

WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic: implementing smoke-free environments.

Geneva

World Health Organization

85. JhaP

ChaloupkaFJ

2000

Tobacco control in developing countries.

Oxford

Oxford University Press

86. LightwoodJM

GlantzSA

2009

Declines in acute myocardial infarction after smoke-free laws and individual risk attributable to secondhand smoke.

Circulation

120

1373

1379

87. SargentRP

ShepardRM

GlantzSA

2004

Reduced incidence of admissions for myocardial infarction associated with public smoking ban: before and after study.

BMJ

328

977

980

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 12- Není statin jako statin aneb praktický přehled rozdílů jednotlivých molekul

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

- Moje zkušenosti s Magnosolvem podávaným pacientům jako profylaxe migrény a u pacientů s diagnostikovanou spazmofilní tetanií i při normomagnezémii - MUDr. Dana Pecharová, neurolog

- Biomarker NT-proBNP má v praxi široké využití. Usnadněte si jeho vyšetření POCT analyzátorem Afias 1

- S prof. Vladimírem Paličkou o racionální suplementaci kalcia a vitaminu D v každodenní praxi

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Clinical Features and Serum Biomarkers in HIV Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome after Cryptococcal Meningitis: A Prospective Cohort Study

- Scaling Up the 2010 World Health Organization HIV Treatment Guidelines in Resource-Limited Settings: A Model-Based Analysis

- Toward a Consensus on Guiding Principles for Health Systems Strengthening

- Association of Secondhand Smoke Exposure with Pediatric Invasive Bacterial Disease and Bacterial Carriage: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- The Health Crisis of Tuberculosis in Prisons Extends beyond the Prison Walls

- A Longitudinal Study of Medicaid Coverage for Tobacco Dependence Treatments in Massachusetts and Associated Decreases in Hospitalizations for Cardiovascular Disease

- Participatory Epidemiology: Use of Mobile Phones for Community-Based Health Reporting

- Nuclear Receptor Expression Defines a Set of Prognostic Biomarkers for Lung Cancer

- Antibiotic Selection Pressure and Macrolide Resistance in Nasopharyngeal A Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial

- Clinical Benefits, Costs, and Cost-Effectiveness of Neonatal Intensive Care in Mexico

- Tuberculosis Incidence in Prisons: A Systematic Review

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Clinical Features and Serum Biomarkers in HIV Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome after Cryptococcal Meningitis: A Prospective Cohort Study

- Participatory Epidemiology: Use of Mobile Phones for Community-Based Health Reporting

- Clinical Benefits, Costs, and Cost-Effectiveness of Neonatal Intensive Care in Mexico

- Scaling Up the 2010 World Health Organization HIV Treatment Guidelines in Resource-Limited Settings: A Model-Based Analysis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání