-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaA Médecins Sans Frontières Ethics Framework for Humanitarian Innovation

Kiran Jobanputra and colleagues describe an ethics framework to support the ethics oversight of innovation projects in medical humanitarian contexts.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 13(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002111

Category: Health in Action

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002111Summary

Kiran Jobanputra and colleagues describe an ethics framework to support the ethics oversight of innovation projects in medical humanitarian contexts.

Summary Points

Humanitarian organisations often have to innovate to deliver health care and aid to populations in complex and volatile contexts.

Innovation projects can involve ethical risks and have consequences for populations even if human participants are not directly involved. While high-level principles have been developed for humanitarian innovation, there is a lack of guidance for how these should be applied in practice.

Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) has well-established research ethics frameworks, but application of such frameworks to innovation projects could stifle innovation by introducing regulation disproportionate to the risks involved. In addition, the dynamic processes of innovation do not fit within conventional ethics frameworks.

MSF developed and is piloting an ethics framework for humanitarian innovation that is intended for self-guided use by innovators or project owners to enable them to identify and weigh the harms and benefits of such work and be attentive towards a plurality of ethical considerations.

Background

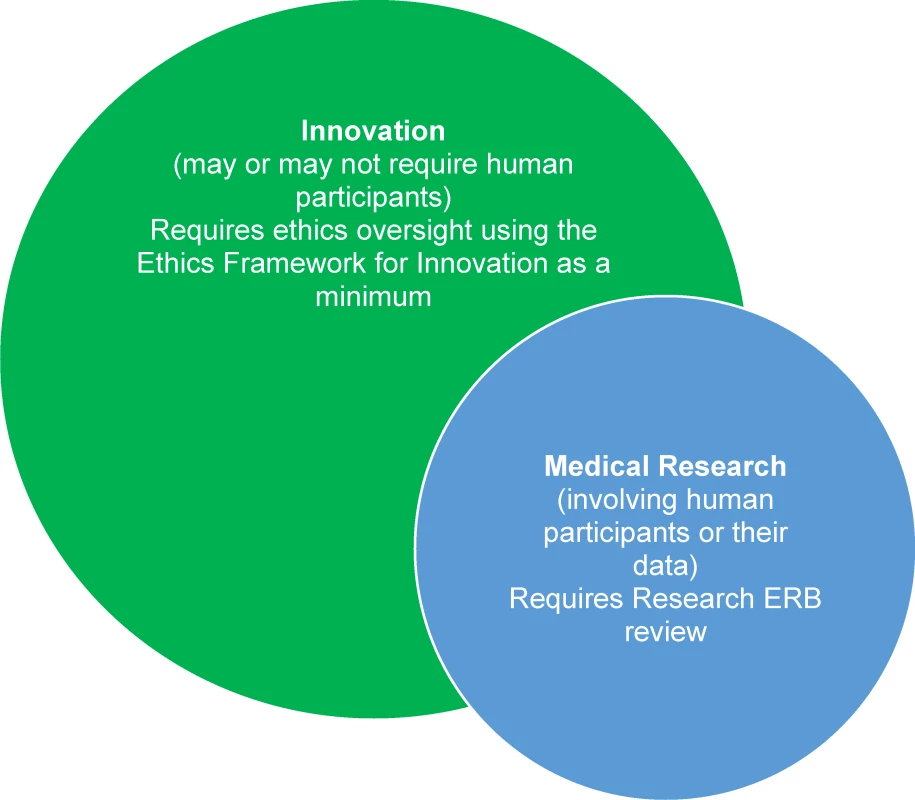

Innovation is at the core of humanitarian action. Humanitarian contexts are often volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous, requiring responders to take a flexible, learning approach. For a medical humanitarian organisation such as Médecins sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF), the challenges of delivering assistance to people in need mean that innovation is an ethical obligation; we cannot rely on old solutions for new problems. For instance, the unprecedented scale of the West African Ebola outbreak presented challenges in patient and data management that required rapid adoption of new tools and methods of working [1,2]. For MSF, innovation involves the creation or implementation of new products or processes to improve quality of care and become more effective in pursuit of our goals of providing medical assistance and “témoignage” (witnessing) to populations in need [3]. Along with intended benefits, however, can come harms, either to the individuals or populations we seek to benefit; to our staff, processes, and reputation; or to the trust placed in us by those in need (Box 1). Well-established ethical guidance exists for medical research in humanitarian settings [4–10]. However, many innovations fall outside the purview of formal research ethics review, and there is a need for ethics guidance for innovations specific to humanitarian action. To address this issue in MSF, we have developed and piloted an ethics framework for innovation projects. Fig 1 outlines the relationship between innovation and research in MSF and clarifies when use of the framework would be appropriate. Research involving human participants, including use of their data, requires approval by the MSF Ethics Review Board (ERB) [6,7], and, similarly, innovation projects that constitute medical research (i.e., involving human participants or their data) should follow the research ethics review process.

Box 1. Harms That May Arise from Innovation Projects

Privacy harms: these include inappropriate use, transfer, or storage of personal data.

Failure to consider the impact of the innovation on the culture, attitudes, or values of the target populations (which may be heterogeneous).

A failure to engage appropriately those likely to be affected by the innovation. Humanitarian innovation must be rooted in a respect for dignity. Parachuting innovations into complex environments without working collaboratively with affected individuals and populations can be perceived as patronizing, undermine trust, and result in failure. It can also lead to wrongs if innovations produce commercial benefits that are not shared with the community.

A failure to consider local solutions. Humanitarian interventions are often characterized by a significant power differential. A failure to identify and (where appropriate) build on local solutions could jeopardize the acceptance and sustainability of an innovation.

Harms to the organization responsible for the innovation, which may subsequently compromise the ability to deliver aid. These include:

Threats to trust: interventions cannot succeed without the trust of the recipient individuals and populations.

Reputational harms (closely linked to trust). Humanitarian agencies depend on their reputations as trusted independent, neutral, and impartial providers of medical relief. Innovation can involve working with nontraditional partners, including commercial providers, governments, or militaries. As such, reputational risks can arise as a result of conflicting partnerships, when partners have agendas that may be—or may be perceived to be—antagonistic to humanitarian goals. Likewise, conflicts of interest may occur when innovators have personal (nonhumanitarian) interests in the innovation.

Fig. 1. Relation between humanitarian innovation and medical research and their oversight in MSF.

The framework is intended for self-guided use by nonmedical innovators (or innovation project owners) with little or no knowledge of medical ethics. Our hope is that it will provide a useful tool to organisations undertaking innovative projects in humanitarian settings by enabling staff to identify and weigh the harms and benefits of such work and be attentive towards a plurality of ethical considerations.

The Need for a Framework

Why not just use existing research ERBs for innovation projects? Importantly, many humanitarian innovation projects do not directly involve human participants or their data, even if they may ultimately have an impact on patient care or services provided for communities. For such projects, the approach to ethics oversight should be proportionate to the reasonably foreseeable harms. In seeking innovative solutions, ethical judgements may need to be made that require potential benefits and harms to be identified and weighed. However, excessive or disproportionate regulation could stifle innovation such that potential benefits could be lost [11]. MSF, as an organization, wants to create an environment conducive to innovation without imposing excessive or disproportionate bureaucratic oversight. This tension between the imperative to innovate and the need to avoid or mitigate harm was key to the decision to develop our ethics framework. Furthermore, innovation is a dynamic process, seldom a one-off event. It involves identifying problems, developing and selecting possible solutions, preliminary implementation and testing, and, where merited, widespread adoption [12]. An ethics framework for innovation should therefore not be an initial hurdle to be jumped but a guide that promotes and informs reflection throughout the innovation cycle.

Deriving an Ethics Framework for Humanitarian Innovation

The framework was developed through an iterative discursive process between senior MSF medical and operations managers and bioethicists with experience in humanitarian medical programming and service delivery. The starting point was our core humanitarian values of neutrality and impartiality [3]. The emerging framework was reviewed in light of literature on biomedical and research ethics as well as ethics of humanitarian innovation [3,4,11,13–16]. Two resources were particularly important: firstly, the MSF Research Ethics Framework, which elaborates key concerns in planning and enacting research, some of which are translatable to innovation projects [4]; secondly, recent elaborations of high-level ethics principles in humanitarian innovation [14,15]. However, one issue that arises when using exclusively high-level principles is the absence of decision-guiding content in specific circumstances—they can leave moral judgment “undetermined” [16]. A major challenge with a principled approach is therefore stepping down from high-level principles to practical decision-making. We thus decided that our framework should capture the moral concerns of the innovation principles from an MSF vantage point that includes the foundation of the MSF Research Ethics Framework [4]. Our intention is to facilitate and focus MSF innovation and thus to be practically oriented in guiding action.

We give particular emphasis to promoting a participatory approach to innovation, as the relationship between humanitarian organisations and the populations they assist can be the source of ethical tensions and opportunities. This also informs the focus of the framework on the needs of particularly vulnerable groups—a central moral concern for MSF. Our framework is not intended to give simple binary outcomes. This is where the hard work of ethical judgment takes place. It involves specifying which of the principles are active in any given decision—that is to say, what the respect for any individual principle means in the context under discussion—and the strength of the claims arising from it. It may also involve weighing the claims arising from different principles and adjudicating between them where they conflict.

A Médecins Sans Frontières Ethics Framework for Humanitarian Innovation

This framework is intended to be used to guide work that does not directly involve human participants and does not lie within the purview of formal research ethics oversight.

Clearly identify the problem you are seeking to address and what benefit you expect the innovation to have. This step may seem obvious, so what is its ethical significance? When identifying the problem, there should be consideration of upstream solutions that may address the problem in a holistic and sustainable way. For instance, rather than focusing on technocratic fixes, what are the sociopolitical determinants of the problem and the wider possibilities for solutions? Who has stakes in finding a solution and who may have interests in perpetuating the problem? Is the problem a moving target? Collaboration and cross-fertilization with other disciplines should be considered in order to help to see the problem from various perspectives. In short, do not underestimate the importance of fully identifying the problem.

Ensure that the innovation shows respect for human dignity. While this is a broad concept, it has practical implications. The focus of concern is respect for human beings, reminding us that the simplest or most direct solutions may not be ethically appropriate. Innovators must show due respect for the multiple and overlapping interests of those affected by the innovation. It extends beyond a concern for physical wellbeing to include psychological and cultural integrity. It also incorporates a concern for individual privacy and a respect for the confidentiality of individual-, family-, and community-based data.

Clarify how you will involve the end user from the start of the process. Innovation should be driven by the requirements of the user. The innovation cycle should be participatory, using methods to involve relevant individuals and communities. Innovators must be sensitive to power dynamics between and within cultures and power imbalances between aid workers and beneficiaries.

Identify and weigh harms and benefits. When considering innovations, a critical first step is the identification, as far as is reasonably possible, of potential harms along with the anticipated benefits. The next step involves weighing these harms and benefits.

Where reasonably foreseeable harms outweigh the likely benefits, implementation will not be ethical. Potential harms include, but are not limited to, physical and psychological harms to individuals. There is also need to consider potential harm to communities.

Where innovation involves a favourable balance of benefits and harms, all reasonable steps must be taken to minimise (mitigate) the harms as far as possible. Unnecessary harms must be eliminated. Where harms are unavoidable, those affected should be informed of the nature and severity of the risks involved.

Conflicted partnerships or conflicts of interest may result in reputational harm to the organisation. If these are identified, then oversight by an existing ERB is recommended.

Describe the distribution of harms and benefits, and ensure that the risk of harm is not borne by those who do not stand to benefit. Innovators need to give careful consideration to the distribution of benefits and harms associated with their projects. Do the risks or benefits fall unequally across groups? If so, is it appropriate to proceed, and how can these inequalities of distribution be addressed or mitigated? Equally, it is important that the innovation takes into account vulnerable groups; it may be ethically warranted to give particular attention to those who have particular needs. Just as we tend to give more health care to the unwell, so particular attention may need to be given to those who are vulnerable or who may not be able to protect their own interests. This is expressed in the humanitarian principle of impartiality. In addition, consider whether anyone is “wronged” by the innovation. A “wrong” is an infringement that is distinct from harm. For example, selecting one group for an innovation project over another may wrong the other group (as opposed to harming them).

Plan (and carry out) an evaluation that delivers the information needed for subsequent decisions to implement or scale-up the innovation, and then ensure that the beneficiaries have access to the innovation. Innovation requires an acceptance of the risk of failure—not all innovation projects will achieve their desired outcome. But in all cases, we can learn and apply these lessons in the future. Given the time, energy, and resources that these projects require, rigorous evaluation and sharing of lessons is itself a moral obligation. Therefore, consideration should be given to dissemination of findings, since it may be important to avoid further exposure to potential harm by sharing findings, whether these are positive or negative. Likewise, there should be a willingness and strategy for wider implementation of the innovation if found to be successful and a commitment to ensure beneficiaries—at least in the communities where it was tested and ideally in similar communities affected by humanitarian crises—have access to the innovation subsequently.

Applying the Framework

The case studies presented in Tables 1–3 are based on analysis of abstracts and slides of conference presentations of MSF innovation projects [17–19]. Project leaders were contacted and gave permission for their project to be analysed and to provide clarification where necessary. Each case study contains a brief outline of the project, analysis of the project using the innovation ethics framework, and conclusions about the ethical considerations raised and what might have been done differently if the framework had been applied at the start of the project. Application of the framework identified ethical concerns in all three of the innovation projects. In addition, the conclusion is reached that many of these concerns could have been mitigated had the framework been applied initially. From discussions at fora such as the annual Humanitarian Innovation Conference [20], it is clear that these issues are not unique to MSF but are common across the humanitarian sector.

Tab. 1. New technology for an old disease: unmanned aerial vehicles for tuberculosis sample transport in Papua New Guinea [<em class="ref">15</em>]. ![New technology for an old disease: unmanned aerial vehicles for tuberculosis sample transport in Papua New Guinea [<em class="ref">15</em>].](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image/2da8fd216d685b2df31ebe9d1010bc29.png)

Tab. 2. The Niger REFRESH borehole project: a paradigm change [<em class="ref">16</em>]. ![The Niger REFRESH borehole project: a paradigm change [<em class="ref">16</em>].](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image/7b6079aba0494a83ba4ca8cab2e8758c.png)

Tab. 3. Mobilisation of local people and technology in mapping for the Sierra Leone Ebola epidemic response [<em class="ref">17</em>]. ![Mobilisation of local people and technology in mapping for the Sierra Leone Ebola epidemic response [<em class="ref">17</em>].](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image/d0aee631e5f1319f1709bff03f9b9275.png)

What Next?

The framework has been shared widely within MSF and made available on the submission site for the MSF Scientific Days conference in May 2016 [21]. All authors submitting an abstract on an innovation project were required to confirm either that the project had undergone formal ethics review (in the case of projects involving formal research with human participants or their data) or that the author had used the framework to critically appraise and oversee their own project together with the project sponsor. The framework as presented here represents a first attempt to generate a robust but user-friendly tool to support the ethics oversight of these innovation projects. We intend to evaluate its use and assess its utility through auditing innovation abstracts and surveying their authors as well as through sharing and conversing with other innovators within and outside MSF.

We believe that this framework will help to improve the quality and learning potential of innovation projects as well as the anticipation of potential harms and (where appropriate) their mitigation. Far from discouraging innovation, we hope that this framework will contribute towards a culture of responsible and informed medical humanitarian innovation.

Zdroje

1. Gallego MS, Deneweth W, Adamson B, Vincent-Smith R, Verdonck G. Project ELEOS: a barcode/handheld-computer based solution for Ebola Management Centres. MSF Scientific Day, London, UK; May 7, 2015. http://www.msf.org.uk/sites/uk/files/3._16_silva_gallego_e-health_ocb_sv_edit_final.pdf.

2. Gayton I, Shankar G, Achar J, Greig J, Crossan S, Yee K-P. A tablet-based clinical management tool: building technology for Ebola Management Centres. MSF Scientific Day, London, UK; May 7, 2015. http://www.msf.org.uk/sites/uk/files/4._28_gayton_e-health_oca_sv_final.pdf.

3. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). MSF Charter and principles. http://www.msf.org/msf-charter-and-principles.

4. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). (2013) MSF Research Ethics Framework–Guidance Document (November 2013). http://fieldresearch.msf.org/msf/handle/10144/305288.

5. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). MSF Ethics Review Board Ethics Review Research Template (November 2013). http://fieldresearch.msf.org/msf/handle/10144/347132.

6. Schopper D, Dawson A, Upshur R, Ahmad A, Jesani A, Ravinetto R, et al. Innovations in research ethics governance in humanitarian settings. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16 : 10. doi: 10.1186/s12910-015-0002-3 25890281

7. Schopper D, Upshur R, Matthys F, Singh JA, Bandewar SS, Ahmad A, et al. (2009) Research Ethics Review in Humanitarian Contexts: The Experience of the Independent Ethics Review Board of Médecins Sans Frontières. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000115 19636356

8. The PLoS Medicine Editors. Ethics Without Borders. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 28;6(7):e1000119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000119 19636357

9. House DR, Marete I, Meslin EM. To research (or not) that is the question: ethical issues in research when medical care is disrupted by political action: a case study from Eldoret, Kenya. J Med Ethics. 2016;42(1):61–65. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2013-101490 26474601

10. Sumathipala A, Siribaddana S. Research and clinical ethics after the tsunami: Sri Lanka. The Lancet. 2005 Oct;366(9495):1418–20.

11. Agich GJ. Ethics and Innovation in Medicine. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2001. http://jme.bmj.com/content/27/5/295.full.

12. Betts A, Bloom L. Humanitarian Innovation: The State of the Art. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 2014. https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/OP9_Understanding%20Innovation_web.pdf.

13. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF (1979). Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press.

14. Oxford University Refugee Studies Centre. Principles for ethical humanitarian innovation. 2015. http://www.oxhip.org/assets/downloads/Principles_for_Ethical_Humanitarian_Innovation_-_final_paper.pdf.

15. International Association of Professionals in Humanitarian Assistance and Protection (PHAP). Live online consultation: Principles for Ethical Humanitarian Innovation. 2015. http://www.elrha.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/150708-Principles-for-Ethical-Humanitarian-Innovation-event-report.pdf.

16. Beauchamp TL. ‘The Four Principles Approach to Health Care Ethics.’ In Ashcroft R.E. et al. (2007) Principles of Health Care Ethics. Chichester: John Wiley.

17. Chikwanha I, Pujo E. New technology for an old disease: unmanned aerial vehicles for tuberculosis sample transport in Papua New Guinea. MSF Scientific Day, London, UK; May 7, 2015. http://www.msf.org.uk/sites/uk/files/1._2_chikwanha_new_operational_models_ocp_sv_final_0.pdf.

18. Nuttinck J-Y, Zongo M, Faure G, Madondo H, Van den Bergh R, Maes P. The Niger REFRESH borehole project: a paradigm change. MSF Scientific Day, London, UK; May 7, 2015. http://www.msf.org.uk/sites/uk/files/2_30_maes_new_models_ocb_sv_final.pdf.

19. Gayton I, Lochlainn LN, Theocharopoulos G, Bockarie S, Caleo G. Mobilisation of local people and technology in mapping for the Sierra Leone Ebola epidemic response. MSF Scientific Day, London, UK; May 7, 2015. http://www.msf.org.uk/sites/uk/files/3_26_lochlainn_gayton_e-health_oca_sv_final_1.pdf.

20. The Humanitarian Innovation Project. Humanitarian Innovation Conference 2015. http://www.oxhip.org/events/hip2015/.

21. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). MSF Scientific Days. http://www.msf.org.uk/msf-scientific-days.

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2016 Číslo 9- Není statin jako statin aneb praktický přehled rozdílů jednotlivých molekul

- S prof. Vladimírem Paličkou o racionální suplementaci kalcia a vitaminu D v každodenní praxi

- Moje zkušenosti s Magnosolvem podávaným pacientům jako profylaxe migrény a u pacientů s diagnostikovanou spazmofilní tetanií i při normomagnezémii - MUDr. Dana Pecharová, neurolog

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

- Biomarker NT-proBNP má v praxi široké využití. Usnadněte si jeho vyšetření POCT analyzátorem Afias 1

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Reporting of Adverse Events in Published and Unpublished Studies of Health Care Interventions: A Systematic Review

- A Public Health Framework for Legalized Retail Marijuana Based on the US Experience: Avoiding a New Tobacco Industry

- Improving Research into Models of Maternity Care to Inform Decision Making

- Associations between Extending Access to Primary Care and Emergency Department Visits: A Difference-In-Differences Analysis

- Sex Differences in Tuberculosis Burden and Notifications in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Use by Breastfeeding HIV-Uninfected Women: A Prospective Short-Term Study of Antiretroviral Excretion in Breast Milk and Infant Absorption

- A Comparison of Midwife-Led and Medical-Led Models of Care and Their Relationship to Adverse Fetal and Neonatal Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study in New Zealand

- Scheduled Intermittent Screening with Rapid Diagnostic Tests and Treatment with Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine versus Intermittent Preventive Therapy with Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine for Malaria in Pregnancy in Malawi: An Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial

- Tenofovir Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women at Risk of HIV Infection: The Time is Now

- The Policy Dystopia Model: An Interpretive Analysis of Tobacco Industry Political Activity

- International Criteria for Acute Kidney Injury: Advantages and Remaining Challenges

- Chronic Kidney Disease in Primary Care: Outcomes after Five Years in a Prospective Cohort Study

- Potential for Controlling Cholera Using a Ring Vaccination Strategy: Re-analysis of Data from a Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial

- Association between Adult Height and Risk of Colorectal, Lung, and Prostate Cancer: Results from Meta-analyses of Prospective Studies and Mendelian Randomization Analyses

- The Incidence Patterns Model to Estimate the Distribution of New HIV Infections in Sub-Saharan Africa: Development and Validation of a Mathematical Model

- Antimicrobial Resistance: Is the World UNprepared?

- A Médecins Sans Frontières Ethics Framework for Humanitarian Innovation

- Reduced Emergency Department Utilization after Increased Access to Primary Care

- "The Policy Dystopia Model": Implications for Health Advocates and Democratic Governance

- Interplay between Diagnostic Criteria and Prognostic Accuracy in Chronic Kidney Disease

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Sex Differences in Tuberculosis Burden and Notifications in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- International Criteria for Acute Kidney Injury: Advantages and Remaining Challenges

- Potential for Controlling Cholera Using a Ring Vaccination Strategy: Re-analysis of Data from a Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial

- The Policy Dystopia Model: An Interpretive Analysis of Tobacco Industry Political Activity

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání