-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 9(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001242

Category: Essay

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001242Summary

article has not abstract

This article was commissioned for the PLoS Medicine series on Big Food that examines the activities and influence of the food and beverage industry in the health arena.

As the PLoS Medicine series on Big Food (www.ploscollections.org/bigfood) kicks off, let's begin this Essay with a blunt conclusion: Global food systems are not meeting the world's dietary needs [1]. About one billion people are hungry, while two billion people are overweight [2]. India, for example, is experiencing rises in both: since 1995 an additional 65 million people are malnourished, and one in five adults is now overweight [3],[4]. This coexistence of food insecurity and obesity may seem like a paradox [5], but over - and undernutrition reflect two facets of malnutrition [6]. Underlying both is a common factor: food systems are not driven to deliver optimal human diets but to maximize profits. For people living in poverty, this means either exclusion from development (and consequent food insecurity) or eating low-cost, highly processed foods lacking in nutrition and rich in sugar, salt, and saturated fats (and consequent overweight and obesity).

To understand who is responsible for these nutritional failures, it is first necessary to ask: Who rules global food systems? By and large it's “Big Food,” by which we refer to multinational food and beverage companies with huge and concentrated market power [7],[8]. In the United States, the ten largest food companies control over half of all food sales [9] and worldwide this proportion is about 15% and rising. More than half of global soft drinks are produced by large multinational companies, mainly Coca-Cola and PepsiCo [10]. Three-fourths of world food sales involve processed foods, for which the largest manufacturers hold over a third of the global market [11]. The world's food system is not a competitive marketplace of small producers but an oligopoly. What people eat is increasingly driven by a few multinational food companies [12].

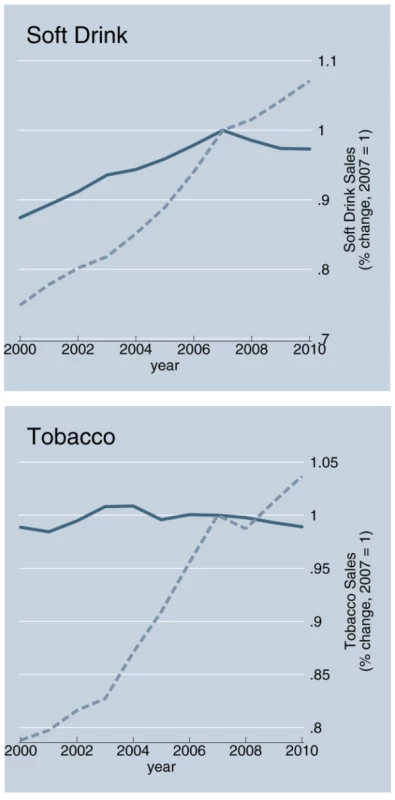

Virtually all growth in Big Food's sales occurs in developing countries [13] (see Figure 1). The saturation of markets in developed countries [14], along with the lure of the 20% of income people spend on average on food globally, has stimulated Big Food to seek global expansion. Its rapid entry into markets in low - and middle-income countries (LMICs) is a result of mass-marketing campaigns and foreign investment, principally through takeovers of domestic food companies [15]. Trade plays a minimal role and accounts for only about 6% of global processed food sales [15]. Global producers are the main reason why the “nutrition transition” from traditional, simple diets to highly processed foods is accelerating [16],[17].

Fig. 1. Growth of Big Food and Big Tobacco sales in developing countries: An example.

Shaded blue line is developed countries, dashed grey line is developing countries. Source: Passport Global Market Information Database: EuroMonitor International, 2011 [12]. Big Food is a driving force behind the global rise in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) and processed foods enriched in salt, sugar, and fat [13]. Increasing consumption of Big Food's products tracks closely with rising levels of obesity and diabetes [18]. Evidence shows that SSBs are major contributors to childhood obesity [19],[20], as well as to long-term weight-gain, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [21],[22]. Studies also link frequent consumption of highly processed foods with weight gain and associated diseases [23].

Of course, Big Food may also bring benefits—improved economic performance through increased technology and know-how and reduced risks of undernutrition—to local partners [24]. The extent of these benefits is debatable, however, in view of negative effects on farmers and on domestic producers and food prices [25].

Public Health Response to Big Food: A Failure to Act

Public health professionals have been slow to respond to such nutritional threats in developed countries and even slower still in developing countries. Thanks to insights from tobacco company documents, we have learned a great deal about how this industry sought to avoid or flout public health interventions that might threaten their profits. We now have considerable evidence that food and beverage companies use similar tactics to undermine public health responses such as taxation and regulation [26],[27],[28],[29], an unsurprising observation given the flows of people, funds, and activities between Big Tobacco and Big Food. Yet the public health response to Big Food has been minimal.

We can think of multiple reasons for the failure to act [30]. One is the belated recognition of the importance of obesity to the burden of disease in LMICs [13]. The 2011 Political Declaration of the United Nations High-Level Meeting on Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) recognized the urgent case for addressing the major avoidable causes of death and disability [31], but did not even mention the roles of agribusiness and processed foods in obesity. Despite evidence to the contrary, some development agencies continue to view obesity as a “disease of affluence” and a sign of progress in combating undernutrition [32].

A more uncomfortable reason is that action requires tackling vested interests, especially the powerful Big Food companies with strong ties to and influence over national governments. This is difficult terrain for many public health scientists. It took five decades after the initial studies linking tobacco and cancer for effective public health policies to be put in place, with enormous cost to human health. Must we wait five decades to respond to the similar effects of Big Food?

If we are going to get serious about such nutritional issues, we must make choices about how to engage with Big Food. Whether, and under what circumstances, we should view food companies as “partners” or as part of the solution to rising rates of obesity and associated chronic diseases is a matter of much current debate, as indicated by the diverse views of officials of PepsiCo and nutrition scientists [24],[27],[28],[33],[34].

Engaging with Big Food—Three Views

We see three possible ways to view this debate. The first favors voluntary self-regulation, and requires no further engagement by the public health community. Those who share this view argue that market forces will self-correct the negative externalities resulting from higher intake of risky commodities. Informed individuals, they say, will choose whether to eat unhealthy foods and need not be subjected to public health paternalism. On this basis, UN secretary-general Ban Ki Moon urged industry to be more responsible: “I especially call on corporations that profit from selling processed foods to children to act with the utmost integrity. I refer not only to food manufacturers, but also the media, marketing and advertising companies that play central roles in these enterprises” [35]. Similarly, the UK Health Minister recently said: “the food and drinks industry should be seen, not just as part of the problem, but part of the solution…An emphasis on prevention, physical activity and personal and corporate responsibility could, alongside unified Government action, make a big difference” [36].

The second view favors partnerships with industry. Public health advocates who hold this view may take jobs with industry in order to make positive changes from within, or actively seek partnerships and alliances with food companies. Food, they say, is not tobacco. Whereas tobacco is demonstrably harmful in all forms and levels of consumption, food is not. We can live without tobacco, but we all must eat. Therefore, this view holds that we must work with Big Food to make healthier products and market them more responsibly.

The third approach is critical of both. It recognizes the inherent conflicts of interest between corporations that profit from unhealthy food and public health collaborations. Because growth in profit is the primary goal of corporations, self-regulation and working from within are doomed to fail. Most proponents of this viewpoint support public regulation as the only meaningful approach, although some propose having public health expert committees set standards and monitor industry performance in improving the nutritional quality of food products and in marketing the products to children.

We support the critical view, for several reasons. First, we find no evidence for an alignment of public health interest in curbing obesity with that of the food and beverage industry. Any partnership must create profit for the industry, which has a legal mandate to maximize wealth for shareholders. We also see no obvious, established, or legitimate mechanism through which public health professionals might increase Big Food's profits.

Big Food attains profit by expanding markets to reach more people, increasing people's sense of hunger so that they buy more food, and increasing profit margins through encouraging consumption of products with higher price/cost surpluses [28]–[31],[37]. Industry achieves these goals through food processing and marketing, and we are aware of no evidence for health gains through partnerships in either domain. Although in theory minimal processing of foods can improve nutritional content, in practice most processing is done so to increase palatability, shelf-life, and transportability, processes that reduce nutritional quality. Processed foods are not necessary for survival, and few individuals are sufficiently well-informed or even capable of overcoming marketing and cost hurdles [38]. Big Food companies have the resources to recruit leading nutritional scientists and experts to guide product development and reformulation, leaving the role of public health advisors uncertain.

To promote health, industry would need to make and market healthier foods so as to shift consumption away from highly processed, unhealthy foods. Yet, such healthier foods are inherently less profitable. The only ways the industry could preserve profit is either to undermine public health attempts to tax and regulate or to get people to eat more healthy food while continuing to eat profitable unhealthy foods [33],[39]. Neither is desirable from a nutritional standpoint. Whereas industry support for research might be seen as one place to align interests, studies funded by industry are 4 - to 8-fold more likely to support conclusions favorable to the industry [40].

Our second reason to support the critical view has to do with the “precautionary principle” [41]. Because it is unclear whether inherent conflicts of interest can be reconciled, we favor proceeding on the basis of evidence. As George Orwell put it, “saints should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent.” We believe the onus of proof is on the food industry. If food companies can rigorously and independently establish self-regulation or private–public partnerships as improving both health and profit, these methods should be extended and replicated. But to date self-regulation has largely failed to meet stated objectives [42],[43],[44],[45],[46],[47], and instead has resulted in significant pressure for public regulation. Kraft's decision to ban trans fats, for example, occurred under pressure of lawsuits [48]. If industry believed that self-regulation would increase profit, it would already be regulating itself.

We believe the critical view has much to offer. It is a model of dynamic and dialectic engagement. It will increase pressures on industry to improve health performance, and it will encourage those who are sympathetic to the first or second views to effect change from within large food and beverage companies.

Public health professionals must recognize that Big Food's influence on global food systems is a problem, and do what is needed to reach a consensus about how to engage critically. The Conflicts of Interest Coalition, which emerged from concerns about Big Food's influence on the U.N. High-Level Meeting on NCDs, is a good place to start [29],[49]. Public health professionals must place as high a priority on nutrition as they do on HIV, infectious diseases, and other disease threats. They should support initiatives such as restrictions on marketing to children, better nutrition standards for school meals, and taxes on SSBs. The central aim of public health must be to bring into alignment Big Food's profit motives with public health goals. Without taking direct and concerted action to expose and regulate the vested interests of Big Food, epidemics of poverty, hunger, and obesity are likely to become more acute.

Zdroje

1. De SchutterO 2011 Report submitted by the Special Rapporteur on the right to food. Geneva: United Nations Available: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/food/docs/A-HRC-16-49.pdf

2. PatelR 2008 Stuffed and starved: The hidden battle for the world food system: Melville House. 448 p

3. DoakCAdairLSBentleyM 2005 The dual burden household and nutrition transition paradox. Int J Obesity 29 129 136

4. SteinADThompsonAMWatersA 2005 Childhood growth and chronic disease: evidence from countries undergoing the nutrition transition. Matern Child Nutr 1 177 184 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16881898

5. CaballeroB 2005 A nutrition paradox – underweight and obesity in developing countries. N Engl J Med 352 1514 1516

6. EckholmERecordF 1976 The two faces of malnutrition. Worldwatch Available: http://www.worldwatch.org/bookstore/publication/worldwatch-paper-9-two-faces-malnutrition

7. PollanM 2003 The (agri)cultural contradictions of obesity. New York Times Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2003/10/12/magazine/12WWLN.html

8. BrownellKWarnerKE 2009 The perils of ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big Food? Milbank Quarterly 87 259 294

9. LysonTRaymerAL 2000 Stalking the wily multinational: power and control in the US food system. Agric Human Values 17 199 208

10. AlexanderEYachDMensahGA 2011 Major multinational food and beverage companies and informal sector contributions to global food consumption: Implications for nutrition policy. Global Health 7 26

11. AlfrancaORamaRTunzelmannN 2003 Technological fields and concentration of innovation among food and beverage multinationals. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 5

12. EuroMonitor International 2011 Passport Global Market Information Database: EuroMonitor International.

13. StucklerDMcKeeMEbrahimSBasuS 2012 Manufacturing Epidemics: The Role of Global Producers in Increased Consumption of Unhealthy Commodities Including Processed Foods, Alcohol, and Tobacco. PLoS Med 6 e 1001235 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001235

14. HawkesC 2002 Marketing activities of global soft drink and fast food companies in emerging markets: A review. Geneva: World Health Organization Available: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/globalization.diet.and.ncds.pdf

15. RegmiAGehlharM 2005 Processed food trade pressured by evolving global supply chains. Amberwaves: US Department of Agriculture Available: http://www.ers.usda.gov/amberwaves/february05/features/processedfood.htm

16. PopkinB 2002 Part II: What is unique about the experience in lower - and middle-income less-industrialised countries compared with the very-high income countries? The shift in the stages of the nutrition transition differ from past experiences! Public Health Nutr 5 205 214 doi:10.1079/PHN2001295

17. HawkesC 2005 The role of foreign direct investment in the nutrition transition. Public Health Nutri 8 357 365

18. BasuSStuckler, D McKeeMGaleaG 2012 Nutritional drivers of worldwide diabetes: An econometric study of food markets and diabetes prevalence in 173 countries. Public Health Nutrition. In press

19. MalivVSchulzeMBHuFB 2006 Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: A systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 84 274 288

20. MorenoLRodriguezG 2007 Dietary risk factors for development of childhood obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 10 336 341

21. HuFMalikVS 2010 Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Physiol Behav 100 47 54

22. MalikVPopkinBMBrayGADespresJPHuF 2010 Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation 121 1356 1364

23. PereiraMKartashovAIEbbelingCBVan HornLSlatteryML 2005 Fast food habits, weight gain and insulin resistance in a 15-year prospective analysis of the CARDIA study. Lancet 365 36 42

24. YachDFeldmanZABradleyDGKhanM 2010 Can the food industry help tackle the growing burden of undernutrition? Am J Public Health 100 974 980

25. EvenettSJennyF 2011 Trade, competition, and the pricing of commodities. Washington D.C.: Center for Economic Policy Research Available: http://www.voxeu.org/reports/CEPR-CUTS_report.pdf

26. ChopraMDarnton-HillI 2004 Tobacco and obesity epidemics: Not so different after all? BMJ 328 1558 1560

27. LudwigDNestleM 2008 Can the food industry play a constructive role in the obesity epidemic? JAMA 300 1808 1811

28. WiistW 2011 The corporate playbook, health, and democracy: The snack food and beverage industry's tactics in context. StucklerDSiegelK editor. Sick Societies: responding to the global challenge of chronic disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

29. StucklerDBasuSMcKeeM 2011 UN high level meeting on non-communicable diseases: An opportunity for whom? BMJ 343 doi:10.1136/bmj.d5336 d5336

30. StucklerD 2008 Population causes and consequences of leading chronic diseases: A comparative analysis of prevailing explanations. Milbank Quarterly 86 273 326

31. UN General Assembly 2011 Political declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs). New York: UN Available: http://www.un.org/en/ga/ncdmeeting2011/

32. MitchellA 2011 Letter to National Heart Forum about ‘Priority actions for the NCD crisis’. LincolnP editor. London: UK DFID.

33. MonteiroCGomesFSCannonG 2009 The snack attack. Am J Public Health 100 975 981

34. AcharyaTFullerACMensahGAYahcD 2011 The current and future role of the food industry in the prevention and control of chronic diseases: The case of PepsiCo. StucklerDSiegelK . Sick Societies: Responding to the global challenge of chronic disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

35. Ki-MoonB 2011 Remarks to the General Assembly meeting on the prevention and control of non-communicable disease. Geneva: UN Available: http://www.un.org/apps/news/infocus/sgspeeches/statments_full.asp?statID=1299

36. LansleyA 2011 4th plenary meeting. Geneva: UN Available: http://www.ncdalliance.org/sites/default/files/rfiles/Monday%20Sep%2019%203pm.pdf

37. KoplanJBrownellKD 2010 Response of the food and beverage industry to the obesity threat. JAMA 304 1487 1488

38. WansinkB 2007 Mindless eating: Why we eat more than we think. Bantam Books

39. WildeP 2009 Self-regulation and the response to concerns about food and beverage marketing to children in the United States. Nutr Rev 67 155 166

40. LesserLEbbelingCBGooznerMWypijDLudwigDS 2008 Relationship between funding source and conclusion among nutrition-related scientific articles. PLoS Med 4 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040005 e5

41. RaffenspergerCTicknerJ 1999 Protecting public health and the environment: implementing the precautionary principle. Washington D.C.: Island Press

42. LewinALindstromLNestleM 2006 Food industry promises to address childhood obesity: Preliminary evaluation. J Public Health Policy 27 327 348

43. LangT 2006 The food industry, diet, physical activity and health: A review of reported commitments and prctice of 25 of the world's largest food companies. London Oxford Health Alliance

44. SharmaLTeretSPBrownellKD 2010 The food industry and self-regulation: Standards to promote success and to avoid public health failures. Am J Public Health 100 240 246

45. BonellCMcKeeMFletcherAHainesAWilkinsonP 2011 The nudge smudge: misrepresentation of the “nudge” concept in England's public health White Paper. Lancet 377 2158 2159

46. CampbellD 2012 High street outlets ignoring guidelines on providing calorie information. The Guardian. London Available: http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/mar/15/high-street-guidelines-calorie-information

47. HawkesCHarrisJL 2011 An analysis of the content of food industry pledges and marketing to children. Public Health Nutr 14 1403 1414

48. ZernikeK 2004 Lawyers shift focus from Big Tobacco to Big Food. New York Times. New York Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/09/us/lawyers-shift-focus-from-big-tobacco-to-big-food.html

49. Conflicts of Interest Coalition 2011 Statement of Concern.

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 6- Není statin jako statin aneb praktický přehled rozdílů jednotlivých molekul

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

- Moje zkušenosti s Magnosolvem podávaným pacientům jako profylaxe migrény a u pacientů s diagnostikovanou spazmofilní tetanií i při normomagnezémii - MUDr. Dana Pecharová, neurolog

- Biomarker NT-proBNP má v praxi široké využití. Usnadněte si jeho vyšetření POCT analyzátorem Afias 1

- S prof. Vladimírem Paličkou o racionální suplementaci kalcia a vitaminu D v každodenní praxi

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Point-of-Care Tests to Strengthen Health Systems and Save Newborn Lives: The Case of Syphilis

- Tobacco Industry Manipulation of Tobacco Excise and Tobacco Advertising Policies in the Czech Republic: An Analysis of Tobacco Industry Documents

- Global Health Governance and the Commercial Sector: A Documentary Analysis of Tobacco Company Strategies to Influence the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- Why Human Health and Health Ethics Must Be Central to Climate Change Deliberations

- Connecting the Global Climate Change and Public Health Agendas

- Protecting Clinical Trial Participants and Protecting Data Integrity: Are We Meeting the Challenges?

- Food Sovereignty: Power, Gender, and the Right to Food

- Clinical Trials Have Gone Global: Is This a Good Thing?

- Analysing Recent Socioeconomic Trends in Coronary Heart Disease Mortality in England, 2000–2007: A Population Modelling Study

- Soda and Tobacco Industry Corporate Social Responsibility Campaigns: How Do They Compare?

- Series on Big Food: The Food Industry Is Ripe for Scrutiny

- Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health

- Manufacturing Epidemics: The Role of Global Producers in Increased Consumption of Unhealthy Commodities Including Processed Foods, Alcohol, and Tobacco

- A Multifaceted Intervention to Improve the Quality of Care of Children in District Hospitals in Kenya: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

- Reproductive Outcomes Following Ectopic Pregnancy: Register-Based Retrospective Cohort Study

- Nevirapine- Versus Lopinavir/Ritonavir-Based Initial Therapy for HIV-1 Infection among Women in Africa: A Randomized Trial

- Long-Term Risk of Incident Type 2 Diabetes and Measures of Overall and Regional Obesity: The EPIC-InterAct Case-Cohort Study

- Comparative Performance of Private and Public Healthcare Systems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review

- Bacterial Vaginosis Associated with Increased Risk of Female-to-Male HIV-1 Transmission: A Prospective Cohort Analysis among African Couples

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Tobacco Industry Manipulation of Tobacco Excise and Tobacco Advertising Policies in the Czech Republic: An Analysis of Tobacco Industry Documents

- Why Human Health and Health Ethics Must Be Central to Climate Change Deliberations

- Clinical Trials Have Gone Global: Is This a Good Thing?

- Point-of-Care Tests to Strengthen Health Systems and Save Newborn Lives: The Case of Syphilis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání