-

Medical journals

- Career

GUNSHOT INJURIES OF THE OROFACIAL REGION

Authors: A. Oskera 1; O. Res 1; J. Timkovic 2; A. Kopecký 2; M. Paciorek 3; Karol Zeleník 4; P. Handlos 5; J. Stránský 1; J. Stembirek 1,6

Authors‘ workplace: University Hospital Ostrava, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Ostrava, Czech Republic 1; University Hospital Ostrava, Department of Ophthalmology, Ostrava, Czech Republic 2; University Hospital Ostrava, Department of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery, Ostrava, Czech Republic 3; University Hospital Ostrava, Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Ostrava, Czech Republic 4; University Hospital Ostrava, Institute of Forensic Medicine, Ostrava, Czech Republic 5; Czech Academy of Sciences, Institute of Animal Physiology and Genetics, Laboratory of Molecular Morphogenesis, Brno, Czech Republic 6

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 62, 1-2, 2020, pp. 24-28

INTRODUCTION

Gunshot wounds of the orofacial region are not very common in peacetime, they, however, represent a type of injury requiring a complex coordinated interdisciplinary care. Life-threatening comminuted fractures of the splanchnocranium and injuries leading to a loss of the soft tissues occur to a varying degree depending on the structure of the affected tissues as well as on the type, shape and energy of the projectile. Regardless of whether the injury is due to a suicide attempt (which is the most common), accident or an attack by another person, stabilisation of the principal vital function of the injured person according to the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol plays a crucial role in the first stage. Only after this stabilisation and a detailed examination of the extent and character of the injuries, surgical reconstruction (in a single or multiple surgeries) can take place.

82% of suicides or suicide attempts by firearms (or, more generally, projectile weapons) lead to injuries to the head1. The projectile entry wound was usually in the temporal or submental region of the head. The aim of this paper is to describe the destructive effects of a projectile in the orofacial region and the recommended procedure in the primary treatment. The team of authors aimed to clearly present important information originating both from literature and practical experience with this type of injury.

EVALUATION OF THE TOPIC

Weapon and projectile types

Projectile weapons can be divided into mechanical (bow, crossbow, catapults, etc.), gas guns (propelled by compressed gas and its subsequent expansion – air gun, paintball gun, airsoft gun) and firearms defined as “projectile weapons in which the energy necessary for expelling the projectile is supplied by rapid combustion (explosion) of an explosive substance (gunpowder)“2.

This paper will discuss the injuries caused by firearms. Those can be further classified according to the used ammunition into single bullet (single - or multiple-barrelled firearms with one or multiple barrels serving for shooting single bullets, projectiles or other shots intended for such use) and shotguns (single - or multiple-barrelled firearms ejecting multiple pellets instead of a single bullet)2.

Bullets used in guns can be jacketed (with a greater penetration effect), semi-jacketed (deforming or fragmenting after impact to achieve an increased wounding capacity – forbidden for civilian use). Cluster shots (shotgun shells) consist of multiple pellets of identical size2.

Mechanism of shot damage to the tissue

The wounding effect is directly proportional to its energy (mV2/2) but depends also on many other parameters including jacketing or shape of the bullet3. Upon impact and entry of the projectile into the body, crushing, cavitation and stress wave occur to various degrees3. Crushing is a dominant mechanism in low-velocity projectiles transferring the major part of their kinetic energy to the surrounding tissues3,4. The term “cavitation” describes the repeated process of cavity formation and collapse in soft tissues. The cavitation mechanism of injury is predominant in high-velocity projectiles. The terms “stress wave” means the transfer of kinetic energy into tissues surrounding the wound channel. Per the Huygens principle, refraction causes multiplication of the damage in the regions of tissue borders – typically, muscle disinsertion or damage to the vascular endothelia3,5,6.

Types of gunshot injuries

The extent of the injury depends to a great degree on the energy load of the projectile. If the projectile energy is low, non-penetration injuries are common; if the bullets hit the body tangentially, we speak of grazing (or glazing) injuries. Shots with higher kinetic energy may either penetrate or perforate the body. The shape, extent and character of the gunshot wound depend besides the bullet energy, shape and properties also on the shooting range and the part of the body that was hit. If shot from the point-blank or close range, the shape of the entry wound depends on the shooting angle and shot calibre. The entry wound is characterised by an actual loss of tissue with an abrasion collar caused by the abrasion of the superficial parts of the skin during penetration. It can be surrounded by complementary gunshot factors (searing, soot, gunpowder tattoo). The exit wound, on the other hand, is usually rather of a lacerated character with a stellate, crescent or irregular rim, the individual parts of which fit together. The complementary factors of the entry wound are also missing. The wound channel also depends on many factors including the speed, calibre, mass, shape, construction and stability of the projectile as well as on the elasticity, viscosity, density and anatomical structure of the tissue. If the projectile breaks into secondary fragments, extremely complicated injuries can be expected4,5,6.

In the orofacial region, projectile trapping can occur most commonly in the immediate vicinity of bones, in particular in low-energy projectiles or where multiple bones (or hard tissues in general) can be found in the projectile trajectory. The shooting channel is usually not completely straight – the changes in the density of the surrounding tissues lead to changes in turning the projectile in the long axis. In general, it can be said that the more the long axis deviates from the straight path, the more devastating are the effects on the surrounding tissues (in other words, the bigger is the cross-section of the projectile in the shot direction, the bigger is the drag of the projectile on the surrounding tissues and the greater is the damage)5,6,7.

The pre-surgical stage from the surgeon’s point of view

Shot wounds of the face can threaten vital structures and therefore, they must be attended to with maximum care. The basic life-saving tasks should follow the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol. The mnemonic ABCDE sets the basic priorities of the primary evaluation and defines the specific order of the individual examinations and interventions necessary in all trauma cases8,9,10.

Airway (airway check + immobilisation of the cervical spine)

- Breathing (evaluation of ventilation)

- Circulation (examination of circulation and bleeding)

- Disability (examination of the neurological condition)

- Exposure (undressing the patient and examination of body temperature)

Airway – it is necessary to evaluate if the airway is free and, if not so, securing it. It is necessary to consider a possible aspiration of fragments of teeth, bones, dentures or blood, as well as the potential instability of the tongue that can lead to obstruction of the airway. Endotracheal intubation can be used to secure the airway; if the injury is of greater extent and/or the lower jaw is destroyed, it is preferable to perform a tracheostomy. At the same level, we must take care of stabilising the cervical spine.

Breathing – free airway on itself does not necessarily mean sufficient gas exchange. This depends also on sufficient function of the lungs, thoracic wall, and the diaphragm, hence an examination of the chest is necessary.

Circulation – the most common cause for shock in trauma patients is blood loss with subsequent hypovolemia. Bleeding wounds must be located and resolved. The densely vascularised tissues of the head and neck can cause massive bleeding from soft tissues, in particular from the nose and mouth (tongue)8,9. Ligation of individual arteries may not be effective enough; in some cases, ligation of a whole artery branch can be necessary (e.g. a. facialis below the lower jaw, a. lingualis in the trigonum Pirogovi or angulus Beclardi, or ligation of a. carotis externa in the trigonum caroticum. When bleeding from the nasal cavity, anterior or anterior-posterior nasal packing (usually using a double-balloon catheter) is most commonly performed. If the nasal bleeding continues, coagulation or ligation of a. sphenopalatina or, if need be, a. ethmoidalis anterior and posterior can be done by endoscopic endonasal surgery. Another possibility is a selective embolisation of a branch (or branches) of a. carotis externa (most commonly a. maxilaris and a. sphenopalatina). It is often necessary to use blood transfusion to replace the blood loss8,9,10.

Disability – a brief examination of the neurological findings. Awareness is evaluated using the Glasgow Coma Scale, pupil response and potential spine injury must be considered. Approximately 17 % of patients with facial gunshot wounds show signs of direct brain damage9. In gunshot wounds against the submental region, the injuries to the mandible and maxilla are frequently accompanied by injuries to the orbit and it is, therefore, necessary to consider the damage to the eye globe motility, or the eye globe and optical nerve themselves10,11. Among other things, it is necessary to look for signs of retrobulbar haematoma (obvious exophthalmos) that can, even after a very short time, lead to irreversible pressure damage to the optical nerve. In injuries by shots against the temporal region, the direction of the shot has a major influence on the resulting damage to the eye globe and adjacent tissues10,11.

Exposure – this term means a full undressing of the patient and a detailed examination of all parts of the body to exclude additional injuries (such as ricocheted bullets)12. It is of course necessary to cover the patient after examination to maintain the body temperature.

If possible, it is also beneficial to look for the reasons of the suicidal attempt. In our practice, in one patient we have found a terminal stage of cancer to be a reason for such an attempt.

Clinical examination

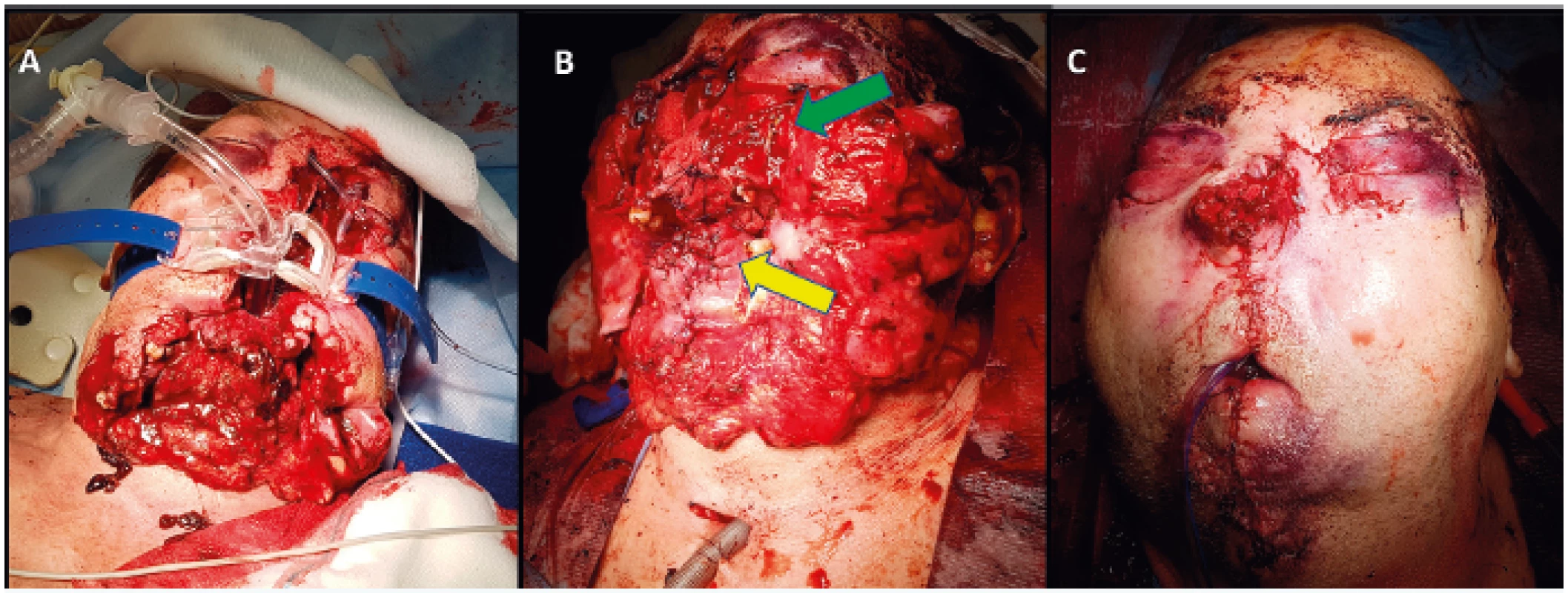

From the surgical perspective, it is necessary to first exclude the direct impact on central nervous system necessitating an urgent neurosurgery consultation or intervention. After that, an examination of the splanchnocranium is performed, which can be difficult due to diffuse bleeding from soft tissues; where loss injuries occur, the wound is also usually very disorganised (Figure 1). It is, therefore, necessary to first identify the source of bleeding12. In the extraoral region, it is important to focus in particular on the examination of visual acuity of each eye separately (if the patient condition allows it), ocular motor control, eye globes, optical nerves and adjacent orbital structures. This should be followed by evaluation of the sensory innervation of all three branches of the n. trigeminus as well as of potential damage to the n. facialis13. Examination of the nasal cavity, evaluating the seriousness of bleeding and assessment of the signs of rhinoliquorrhea should follow. Subsequently, the presence of bleeding from the outer ear canal or oroliquorrhea is evaluated. If any of those are present, a sterile strip is inserted into the outer ear canal and then sent for examination for beta-trace protein. If the patient is conscious, a preliminary check of hearing should be performed using a tuning fork. Once the patient condition is stabilised, an audiometric examination can be performed if the hearing is affected. If possible, we evaluate the presence and character of nystagmus, which can be a sign of either peripheral vestibular lesion or damage to the central nervous system.

1. A) A patient intubated through his mouth following a gunshot injury to the face who was brought to the Accident & Emergency Unit, University Hospital Ostrava. The rigid cervical collar was already removed following a CT examination. B) The patient in the surgical theatre with tracheostomy and nasal packing due to bleeding; the green arrow indicates a primarily reconstructed maxilla and palate, the yellow arrow a reconstructed tongue. A loss injury to the mandible is obvious. C) Primary reconstruction of the face, nose and mouth; the lack of soft tissues is apparent (microstoma, notable lack of the nasal tissues)

Eventually, the extent of soft and hard tissue loss must be evaluated. Assessment of the course of the facial nerve is important. If the wound is in the region of the branches of the facial nerve and those are visible, the primary surgery must always include the finding of the facial nerve branches and if their continuity is damaged, a microscopic suture must be performed. The potential delayed suture of the facial nerve (several weeks later) is much more difficult and the results are significantly worse12,13.

The intraoral examination should follow. Fragments of teeth, bones, prosthetic devices or foreign bodies can be present in the oral cavity12. Occlusion and intercuspidation should be assessed, it is, however (due to the patient condition), not always possible. If this is the case, incisional edges of the frontal teeth or worn out surfaces of the teeth can be helpful12.

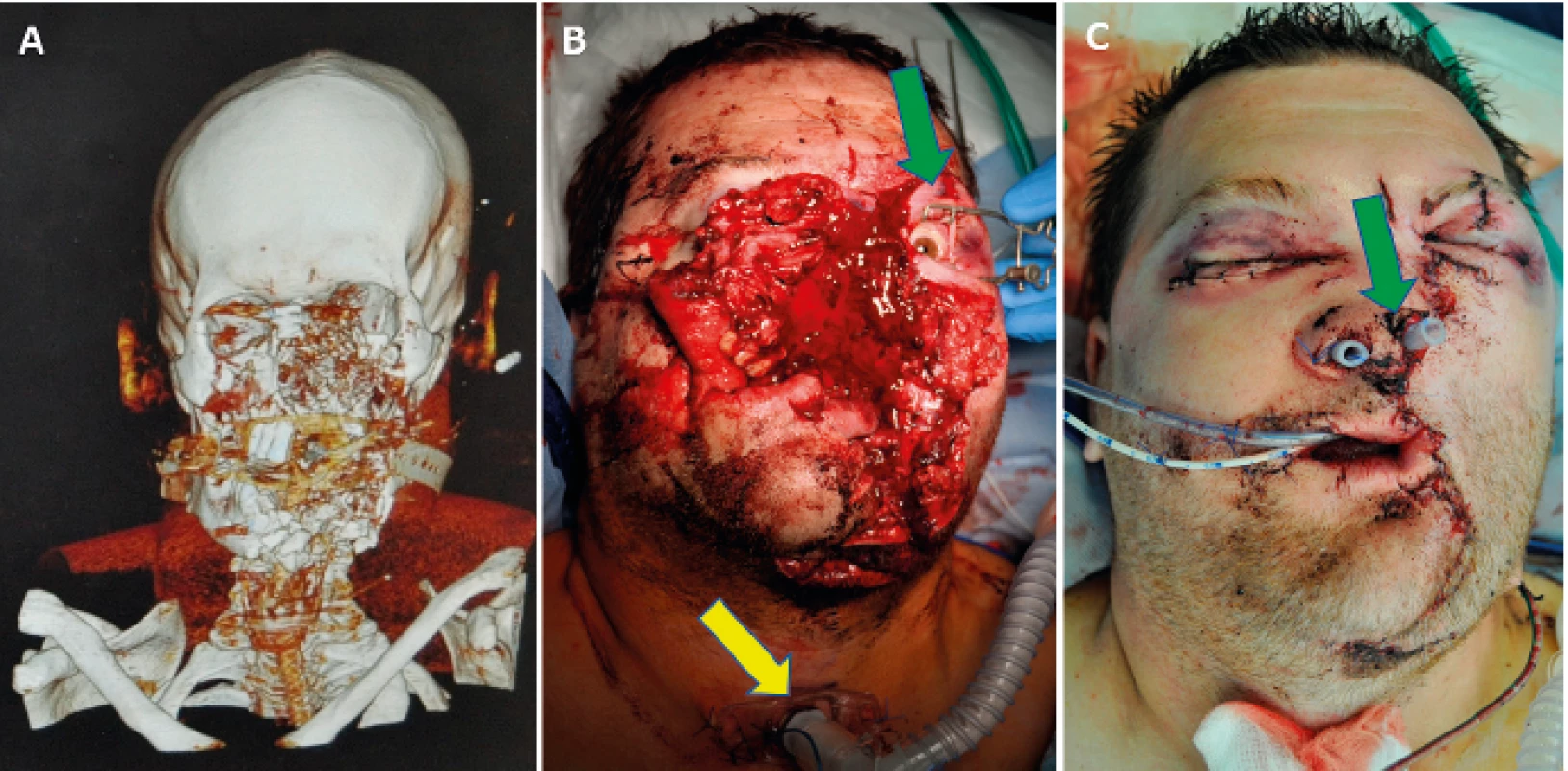

The use of imaging methods is a necessary part of the diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT) of head and neck is a principal imaging method in such cases14. For proper evaluation, at least two mutually perpendicular projections must be taken; if a 3D reconstruction is available, it provides a better general idea of the full extent of the injury (Figure 2).

2. A) CT examination of the same patient with a gunshot injury to the face (intubated through the mouth); the scan shows a comminuted fracture of the lower jaw and a loss injury to the maxilla. B) Eye globe examination using an eyelid opener (green arrow) and tracheostomy (yellow arrow) C) Reconstructed face, the green arrow indicates tubes used for nose reconstruction

Treatment protocol8,9,10

1. Primary life-saving procedures including haemodynamic stabilisation and haemostasis following ATLS guidelines.

2. Imaging methods: Computed tomography (CT) in all gunshot injuries to the splanchnocranium (a 3D reconstruction is desirable).

3. Interdisciplinary patient evaluation (traumatologist, anaesthetist, radiologist, neurosurgeon, neurologist, ENT specialist, maxillofacial surgeon, ophthalmologist, plastic surgeon), diagnosis and classification of the injuries, preparation of a list of diagnoses and establishing priorities of the multidisciplinary treatment protocol.

4. Tracheostomy where extensive loss injuries are concerned (if not performed during the primary life-saving procedures).

5. Treatment of periocular tissues, eye globe(s) and the orbit(s).

6. Stabilisation of the facial skeleton and osteosynthesis of the fragments.

7. If possible, nose reconstruction preserving maximum of soft tissues is desirable.

8. Closure of soft tissue defects (risk of microstoma, lagophthalmos, oronasal and oroantral communication, nose blockage) fully covering the bone fragments.

9. Patient nutrition (nasogastric tube insertion).

CONCLUSION

The extent and severity of the injuries depend, besides the site of the injury, bullet calibre and energy, also on other factors such as the bullet trajectory, formation of secondary projectiles, ricochets/deflections of the projectile from the skeletal structures, etc. In practice, gunshot wounds often cause injuries to the mandible, maxilla, orbit and nose, i.e., to organs requiring broad interdisciplinary cooperation. For clinical practice, the knowledge of the type of the used gun and bullet can be beneficial as it facilitates the possible estimation of the degree of tissue trauma.

The subsequent reconstruction of the orofacial region can represent a major challenge for the entire reconstruction team (Figure 3).

3. A patient 6 months after the primary reconstruction. Scarring and deformation of the entire face are obvious

Author roles: Adam Oskera: review of literature, manuscript writing. Oldrich Res: final manuscript approval, patient treatment Juraj Timkovic: final manuscript approval, patient treatment. Adam Kopecky: final manuscript approval, patient treatment. Martin Paciorek: final manuscript approval, patient treatment. Karol Zelenik: final manuscript approval, patient treatment. Petr Handlos: manuscript writing, final manuscript approval. Jiri Stransky: final manuscript approval, patient treatment. Jan Stembirek manuscript writing, final manuscript approval, patient treatment.

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Grant support: Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic – MZ ČR – RVO – FNOs/2017.

Corresponding author:

Jan Stembirek, MD, MDD, PhD

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery,

University Hospital Ostrava

17. listopadu 1790/5

708 52 Ostrava

Czech Republic

E-mail: jan.stembirek@fno.cz

Sources

1. Český statistický úřad: Zemřelí podle seznamu příčin smrti, pohlaví a věku v ČR, krajích a okresech – 2009 až 2018. Published 20. 11. 2019 [on line] Available from: https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/zemreli-podle-seznamu-pricin-smrti-pohlavi-a-veku-v-cr-krajich-a-okresech-lv8io6up9t.

2. Czech Republic. Act no: 229/2016 Sb., zákon o střelných zbraních. In: Sbírka zákonů. Published 15. 6. 2016.

3. Hirt M. a kol. Soudní lékařství. Grada Publishing 2015, p. 117–146.

4. Cohen MA., Shakenovsky BN., Smith I. Low velocity hand-gun injuries of the maxillofacial region. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986, 14 : 26–33.

5. Stefanopoulos PK., Mikros G., Pinialidis DE., Oikonomakis IN., Tsiatis NE., Janzon BJ. Wound ballistics of military rifle bullets: An update on controversial issues and associated misconceptions. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019, 87 : 690-8.

6. Stefanopoulos PK., Pinialidis DE., Hadjigeorgiou GF., Filippakis KN. Wound ballistics 101: the mechanisms of soft tissue wounding by bullets. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2017, 43 : 579–86.

7. Hanna TN., Shuaib W., Han T., Mehta A., Khosa F. Firearms, bullets, and wound ballistics: an imaging primer. Injury. 2015, 46 : 1186–96.

8. Peled M., Leiser Y., Emodi O., Krausz A. Treatment Protocol for High Velocity/High Energy Gunshot Injuries to the Face, Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2012, 5 : 31–40.

9. Long V., Lo LJ., Chen YR. Facial reconstruction after a Complicated gunshot injury. Chang Gung Med J. 2002, 25 : 557–62.

10. Kihtir T., Ivatury RR., Simon RJ., Nassoura Z., Leban S. Early management of civilian gunshot wounds to the face. J Trauma. 1993, 35 : 569–75.

11. Kopecky A., Rokohl AC., Nemcansky J., Koch KR., Matousek P., Heindl LM. Das retrobulbäre Hämatom – eine potenziell visusbedrohende Komplikation [Retrobulbar Haematoma – a Complication that May Impair Vision] [published online ahead of print, 2019 Aug 15]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2019;10.1055/a-0958-9584. doi:10.1055/a-0958-9584.

12. Hollier L., Grantcharova EP., Kattash M. Facial gunshot wounds: a 4-year experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001, 59 : 277–82.

13. Doctor VS., Farwell DG. Gunshot wounds to the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007, 15 : 213–8.

14. Demetriades D., Chahwan S., Gomez H., Falabella A., Velmahos G., Yamashita D. Initial evaluation and management of gunshot wounds to the face. J Trauma. 1998, 45 : 39–41.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2020 Issue 1-2-

All articles in this issue

- AN OVERVIEW AND OUR APPROACH IN THE TREATMENT OF MALIGNANT CUTANEOUS TUMOURS OF THE HAND

- ENHANCED RECOVERY PROTOCOL FOLLOWING AUTOLOGOUS FREE TISSUE BREAST RECONSTRUCTION

- SKIN SUBSTITUTES IN RECONSTRUCTION SURGERY: THE PRESENT AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

- GUNSHOT INJURIES OF THE OROFACIAL REGION

- INDICATION AND IMPORTANCE OF RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERIES OF FACIAL SKELETON IN MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY: REVIEW

- Editorial

- CURRENT OPTIONS IN PHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS FOR MICROVASCULAR ANASTOMOSIS PATENCY: REVIEW

- ACCIDENTAL FINDING OF SYNCHRONOUS BILATERAL DUCTAL CARCINOMA IN SITU IN A YOUNG MAN REFERRED TO MASTECTOMY DUE TO GYNECOMASTIA – AND WHAT IF LIPOSUCTION HAVE BEEN USED? CASE REPORT

- RED BREAST SYNDROME (RBS) ASSOCIATED TO THE USE OF POLYGLYCOLIC MESH IN BREAST RECONSTRUCTION: A CASE REPORT

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- RED BREAST SYNDROME (RBS) ASSOCIATED TO THE USE OF POLYGLYCOLIC MESH IN BREAST RECONSTRUCTION: A CASE REPORT

- AN OVERVIEW AND OUR APPROACH IN THE TREATMENT OF MALIGNANT CUTANEOUS TUMOURS OF THE HAND

- GUNSHOT INJURIES OF THE OROFACIAL REGION

- SKIN SUBSTITUTES IN RECONSTRUCTION SURGERY: THE PRESENT AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career