-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

A -Regulatory Signature for Chordate Anterior Neuroectodermal Genes

One of the striking findings of comparative developmental genetics was that expression patterns of core transcription factors are extraordinarily conserved in bilaterians. However, it remains unclear whether cis-regulatory elements of their target genes also exhibit common signatures associated with conserved embryonic fields. To address this question, we focused on genes that are active in the anterior neuroectoderm and non-neural ectoderm of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Following the dissection of a prototypic anterior placodal enhancer, we searched all genomic conserved non-coding elements for duplicated motifs around genes showing anterior neuroectodermal expression. Strikingly, we identified an over-represented pentamer motif corresponding to the binding site of the homeodomain protein OTX, which plays a pivotal role in the anterior development of all bilaterian species. Using an in vivo reporter gene assay, we observed that 10 of 23 candidate cis-regulatory elements containing duplicated OTX motifs are active in the anterior neuroectoderm, thus showing that this cis-regulatory signature is predictive of neuroectodermal enhancers. These results show that a common cis-regulatory signature corresponding to K50-Paired homeodomain transcription factors is found in non-coding sequences flanking anterior neuroectodermal genes in chordate embryos. Thus, field-specific selector genes impose architectural constraints in the form of combinations of short tags on their target enhancers. This could account for the strong evolutionary conservation of the regulatory elements controlling field-specific selector genes responsible for body plan formation.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000912

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000912Summary

One of the striking findings of comparative developmental genetics was that expression patterns of core transcription factors are extraordinarily conserved in bilaterians. However, it remains unclear whether cis-regulatory elements of their target genes also exhibit common signatures associated with conserved embryonic fields. To address this question, we focused on genes that are active in the anterior neuroectoderm and non-neural ectoderm of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Following the dissection of a prototypic anterior placodal enhancer, we searched all genomic conserved non-coding elements for duplicated motifs around genes showing anterior neuroectodermal expression. Strikingly, we identified an over-represented pentamer motif corresponding to the binding site of the homeodomain protein OTX, which plays a pivotal role in the anterior development of all bilaterian species. Using an in vivo reporter gene assay, we observed that 10 of 23 candidate cis-regulatory elements containing duplicated OTX motifs are active in the anterior neuroectoderm, thus showing that this cis-regulatory signature is predictive of neuroectodermal enhancers. These results show that a common cis-regulatory signature corresponding to K50-Paired homeodomain transcription factors is found in non-coding sequences flanking anterior neuroectodermal genes in chordate embryos. Thus, field-specific selector genes impose architectural constraints in the form of combinations of short tags on their target enhancers. This could account for the strong evolutionary conservation of the regulatory elements controlling field-specific selector genes responsible for body plan formation.

Introduction

The concept of “selector genes” was introduced 30 years ago by Garcia-Bellido to define genes that interpret a transient regulatory state and specify the identity of a given developmental field [1]. The question of how embryos execute distinct and unique differentiation programs using these selector genes can be tackled by focusing on how gene expression is encoded in cis-regulatory elements and their field-specific trans-acting factors (TF).

This concept was more recently extended to terminal selector genes that coordinate the expression of differentiation genes to determine a given cell type [2]. In vertebrates, examples include the Crx TF that interacts with another TF to control the expression of target genes in rod photoreceptors [3]–[5]. In vertebrates as well as in flies, Crx and its Drosophila homolog Otd act through a small cis-regulatory motif overrepresented in the elements flanking the target genes [6]–[10]. In addition to this evolutionary conserved network, many others in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster have shown that cell specific enhancers contain a common “tag” corresponding to a specific cis-regulatory motif, and that this motif is linked to one or a few terminal selector genes [11], [12]. In contrast, during early development, very few studies have reported how a set of region-specific cis-regulatory elements responds to field-specific selector genes. In insects, one of the best characterized sets of functionally related cis-regulatory elements responds to the gradient of nuclearized dorsal TF in the early Drosophila embryo [13], [14]. However, the regulatory mechanism of dorsal-ventral patterning is not enough conserved in chordates to allow comparative studies of the regulatory network.

A more general character of bilaterians is the tripartite organization of the nervous system along the antero-posterior axis [15]. In the posterior part (hindbrain and nerve cord), Hox genes are expressed in a colinear order. In the domain anterior to the Hox genes, several striking similarities in the relative expression patterns of other transcription factors have been noted in bilaterians [16]–[18]. The OTX-like homeobox transcription factors (otd in insects) are expressed in the anteriormost part of animals as diverse as cnidarians, insects, annelids, urochordates and vertebrates [19]–[21]. In chordates, OTX has a sustained expression in the anterior neuroectoderm and in derivatives of anterior ectoderm such as placodes, stomodeum [20], [22]. In mice, null-mutants of this gene lack various head structures [23]. These results suggest that OTX-like proteins belong to a conserved developmental control system operating in the anterior parts of the brain, different from the one encoded by the Hox complexes [24].

Many homeodomain proteins bind to the core DNA sequence ATTA, but several subfamilies have longer binding specificities around this core [25], [26]. OTX homeodomain proteins contain a lysine at position 50 which confers them additional specificity to guanines 5′ of the ATTA motif, resulting in a core recognition sequence of GATTA/TAATC [27]. The DNA binding domains of homeobox gene families are highly similar over large evolutionary distances and cross-species experiments have demonstrated that the OTX proteins can be exchanged between flies, mice and human without major developmental defects [28], [29], and more recently between ascidians and mice [24], [30].

For studies of anterior nervous system development, the ascidian Ciona intestinalis offers the advantage of a simple chordate body plan with the canonical tripartite brain along the antero-posterior axis [31]. In addition, the genome is small, with short intergenic regions which can be aligned with another ascidian species, thus simplifying the identification of cis-regulatory elements [32]. Moreover, complete expression patterns have been determined for thousands of genes and are readily available in public databases [33]–[35]. Therefore, Ciona intestinalis constitutes an ideal model system for combining whole genome bioinformatics and experimental cis-regulatory analyses.

Here, we first focus on one single anterior ectodermal enhancer in Ciona intestinalis. Its detailed analysis points to an internal tandem-like structure and underscores the key role of the selector gene Otx. We then examine if other duplicated putative binding sites for OTX preferentially flank anteriorly expressed genes in the genome.

Results/Discussion

D1 mediates the initiation of Ci-pitx expression in the anterior neural boundary (ANB)

We have previously described an enhancer sequence (called “D1”, 323bp) that controls expression of the Ciona intestinalis Pitx gene in a sub-region overlapping the neural and the non neural ectoderm called the anterior neural boundary (ANB) [36]. For the sake of simplicity, and although ANB has a dual origin, we label it as a derivative of the neuroectoderm and call the region composed of anterior epidermis, ventro-anterior sensory vesicle and ANB, the “anterior neuroectoderm”. For this study, we used a minimal 206 bp fragment of D1 that is sufficient to drive reporter gene expression in the ANB and divided it into five parts (D1a-e, Figure 1A and Figure 2A) for further analysis. Deletion of the first 16pb (D1a, Figure 2A) resulted in the D1bcde fragment (Figure 1A) and led to ectopic reporter gene expression in the anterior epidermis (ae) and ventro-anterior sensory vesicle (vasv) in addition to the expected expression in the ANB. All these elements indicate that D1 responds to neuroectodermal trans-activating factors that are not restricted to the ANB and that D1a contains motifs bound by a repressor factor that restricts D1 expression to the sole ANB.

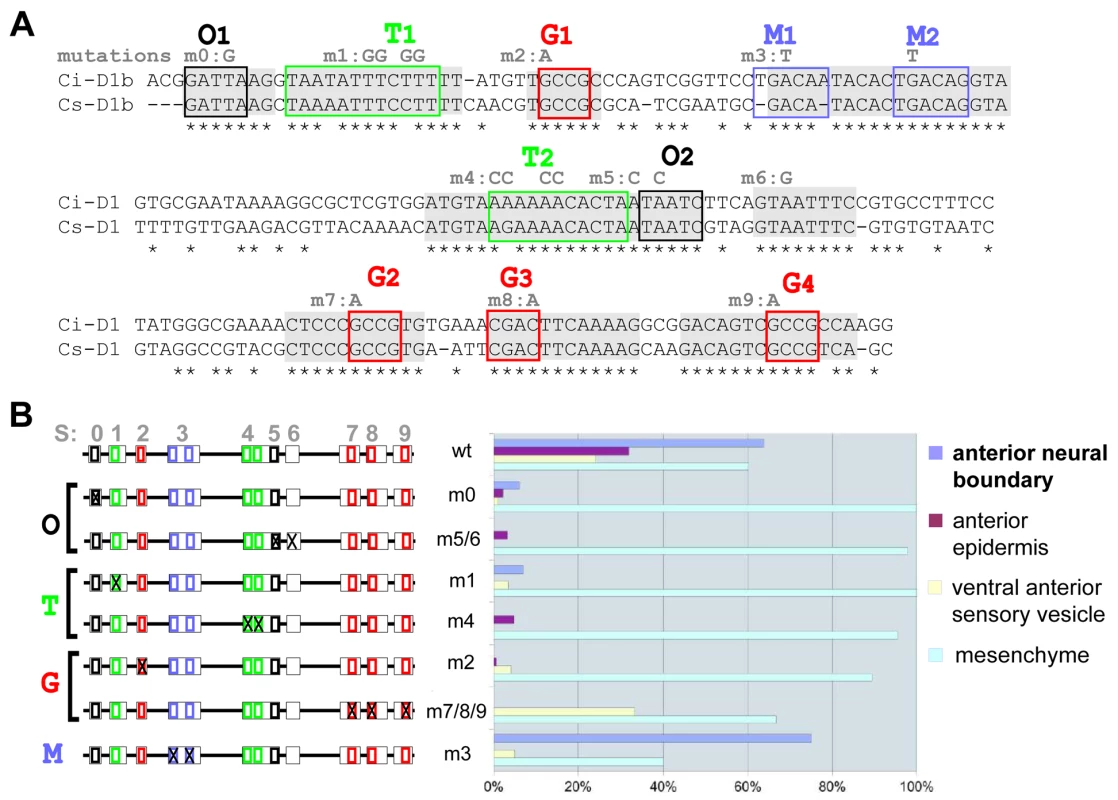

Fig. 1. Mutational analysis of D1(bcde) reveals at least three binding sites necessary for its activity.

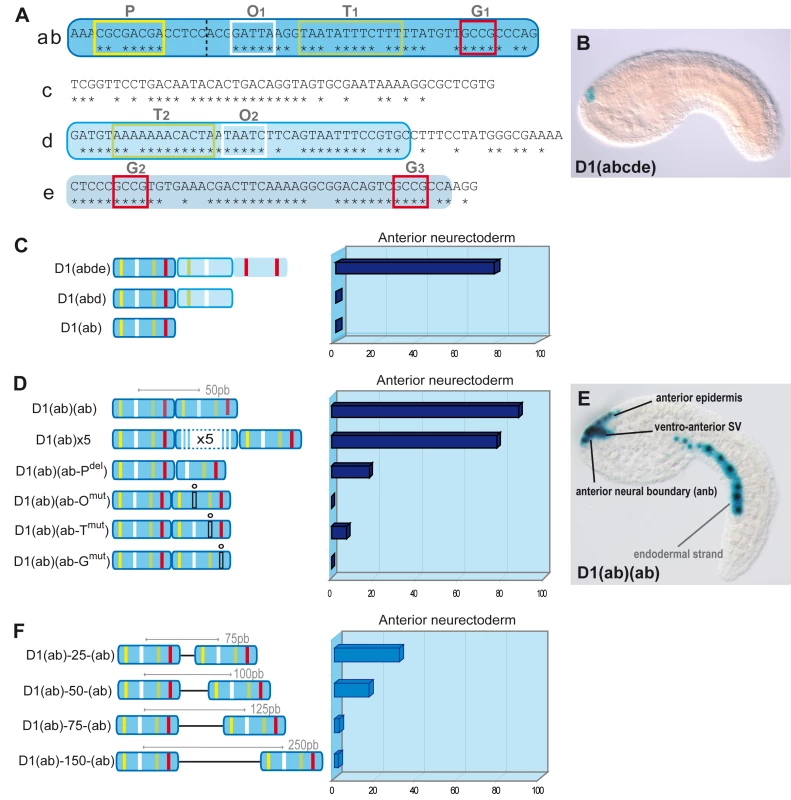

(A) Alignment of D1(bcde) (195pb) between Ci/Cs. Conserved blocks in D1(bcde) with putative transcription factor binding sites (TFBS). Four classes of putative TFBS within ten blocks of conserved sequence: O1 and O2 display the characteristic GATTA/TAATC core sequence that is known to bind K50 Paired-related homeodomain proteins, including otx/otd, pitx and goosecoid. Putative Fox protein binding sites were identified in the blocks called T1 and T2 (T/A-rich). Blocks M1 and M2 show similarity to known binding sites of the TALE-class Meis/TGIF homeodomain proteins. Finally, putative Smad1/5/8 binding sites were observed in blocks labelled G1, G2, G3 (G/C-rich). Conserved blocks of nucleotides are highlighted in grey. Putative binding sites are represented by colored boxes. Mutations designed to disrupt the binding specificity of each sites are indicated in grey above the sequence (m0 to m9). (B) Schematic representation of D1(bcde) and series of mutations introduced into the pD1bcde:CES2 construct. On the right is shown for each construct the rate of mid-tailbud embryos expressing the lacZ reporter in the anterior neural boundary (anb), the anterior epidermis (ae), the ventro-anterior sensory vesicle (vasv) and the mesenchyme (mes) (wt n = 444; m0 n = 198; m1 n = 56; m2 n = 348; m3 n = 40; m4 n = 58; m5/6 n = 182; m7/8/9 n = 29). Most mutations led to a general reduction of the expression level in all of aforementioned domains, while mesenchyme expression remained high. Only construct m3 (block M1 and M2) retained the activity in the anterior neural boundary. Fig. 2. Artificial enhancer constructs reveal a tandem-like structure.

(A) D1(abcde) Ci-Pitx enhancer. Stars show conserved positions with Ciona savignyi. The element has been divided into five parts (a, b, c, d, e). (ab) fragment is in dark blue, (d) in light blue with blue outline, (e) in light blue. Conserved nucleotides stretches contain putative transcription factor binding sites (TF-BS). O1 and O2 sites (white box) correspond to the BS for K-50 Paired homeodomain proteins and P (yellow), T1, T2 (green) and G1, G2, G3 (red) resemble Pax, Forkhead and Smad protein consensus BS respectively. (B) Side view of an early-tailbud embryo electroporated with pD1abcde:CES2:lacZ: expression in the anterior neural boundary (ANB). In some cases, ectopic expression occurs in the mesenchyme and the tail muscles (not shown). (C) Expression of artificial enhancers in the anterior neuroectoderm of mid-tailbud embryos. LacZ expression was observed after two hours of staining. The D1(abde) construct drives lacZ expression in the anterior neuroectoderm (ANB), ventro-anterior sensory vesicle (vasv) and epineural epidermis (ene) in 77.9% of developed embryos (n = 57). Deletions of (e) or (de), but not (c), abolish LacZ expression (D1(abd), D1(ab)). (D) Two (D1(ab)(ab)) or five (D1(ab)×5) copies of the 54bp D1(ab) drive expression in most of the embryos (88% (n = 167) and 77% (n = 72), respectively). Only 17% of the embryos express lacZ following the deletion of the second P site (D1(ab)(ab-Pdel), n = 90). Mutations of O, T, and G sites in the second copy of (ab) strongly decrease lacZ expression. (D1(ab)(ab-Omut): 0% (n = 137), D1(ab)(ab-Tmut): 7% (n = 84), D1(ab)(ab-Gmut): 0% (n = 118)). (E) Mid-tailbud embryo electroporated with pD1(ab)(ab):CES2:lacZ. Expression is visible in the ANB, the vasv, the ene and less frequently in the endodermal strand. (F) Introduction of spacer regions of 25/50/75/150 bp between the two D1(ab) fragments strongly decreased the activity of the tandem constructs. From 88% (D1(ab)(ab)) to 31.6% (n = 76), 16.9% (n = 154), 2.5% (n = 79) and 1.9% (n = 106), respectively. Scores were obtained after one week of LacZ revelation. We tested whether D1bcde controls the onset of Ci-pitx expression in the ANB. Endogenous Ci-Pitx-gene expression was not detected in ANB cells before the initial tailbud stage [37], [38], suggesting that it starts at this stage. To test whether D1bcde recapitulates the temporal pattern of Ci-Pitx expression, we assayed reporter gene expression by either X-gal staining or lacZ in situ hybridization on the same batch of electroporated embryos fixed at successive stages. The rationale is to take advantage of the delay in β-galactosidase protein synthesis (e.g. [39]), which should produce a marked difference between X-gal and in situ staining shortly after the onset of reporter gene expression. We could detect neither lacZ RNAs nor β-galactosidase activity before the initial tailbud stage. At this stage, however, lacZ transcripts could be detected in 55.4% (n = 46 of N = 71) of the embryos while only 7% (n = 5 of N = 83) showed positive ANB cells after X-gal staining (Table S1). Hence, D1bcde-driven transcription starts at the same time as the endogenous pitx gene, which indicates that the D1bcde enhancer element triggers the initiation of Ci-pitx expression in ANB cells.

Short blocks of conserved nucleotides are required for D1 enhancer activity

Conservation between Ciona intestinalis and savignyi genomic sequences is not uniformly distributed throughout conserved non coding elements (CNEs) but rather concentrated in short blocks of identical nucleotides, which point to candidate transcription factor binding sites (TF-BS; Figure 1A, Figure 2A). We identified four classes of putative TF-BS based on nucleotide composition and by querying binding site databases [40], [41]. One of them matches the OTX/K-50 paired homeodomain consensus sequence (sites O1 and O2, Figure 1A and Figure 2A). Other sites, called T (T/A-rich), G (G/C-rich) and M, bear resemblance to Forkhead, Smad and Meis family factors, respectively (Figure 1A). Some of them (P, T1, T2 were not completely conserved in the genome alignment. But each class of these candidate binding sites was represented at least twice in the minimal D1bcde element. The function of these candidate TF-BS was tested by introducing point mutations in the corresponding blocks of conserved sequences, followed by reporter gene expression assays. With the exception of mutations disrupting the “M” sites, each one of the individual modifications of O, T and G sequences reduced reporter gene expression in the anterior neuroectoderm derivatives (Figure 1B). Taken together, these observations indicate that D1 enhancer activity requires at least two copies of each one of three distinct classes of conserved putative TF-BS (Figure 1).

A tandem organization of binding sites is required for D1 activity

The aforementioned observation that the essential putative binding sites occur several times in the enhancer led us to investigate whether the structure of D1 bears functional significance to its enhancer activity. Notably, the 54-bp D1(ab) element (Figure 2A) contains the three previously mentioned conserved motifs O, T and G in addition to a putative Pax binding site (P), but D1(ab) is not sufficient to enhance reporter gene transcription (Figure 2C). Since each of the critical sites is represented at least twice in the full length enhancer, we asked whether D1 enhancer activity relies on this tandem-like repetition of essential binding sites. We created artificial enhancers containing multiple copies of D1(ab) and found that as little as two copies of D1(ab) were sufficient to drive strong lacZ expression in the anterior neuroectoderm (88% of 167 tailbud embryos (Figure 2D and 2E)).

To test whether enhancer activity of the D1(ab) dimer relies specifically on the duplication of O, T and G sites, we introduced point mutations in the second D1(ab) copy. Each of these mutations strongly reduced enhancer activity (Figure 2D). These observations are reminiscent of the requirement for multiple copies of bicoid binding sites for target gene activation during Drosophila head development [42] and the general tendency of binding sites to occur in clusters [43]. Our results demonstrate that duplications of critical binding sites are essential for D1 enhancer activity and do not constitute mere redundancy.

We next asked whether the distance between the duplicated 54bp elements influenced the activity of the artificial D1(ab) dimer. To this aim, we designed sequences that are not predicted to bind any characterized transcription factors from the Uniprobe database (see Materials and Methods) and inserted 25, 50, 75 and 150bp spacers between the D1(ab) duplicates. Overall, enhancer activity of these constructs is reduced compared to the original D1(ab) dimer and almost completely abolished with the 75bp and 150bp spacers (Figure 2F). Similar structural constraints were reported in the Drosophila knirps enhancer, which was shown to require a specific arrangement of duplicated bicoid binding sites for activation [44], [45]. Similarly, even-skipped enhancers contain a conserved structure of paired binding sites [46] and duplicated and relatively distant (30–200bp) TFBS are necessary for a correct activity of the SV40 enhancer [47] and the lac operon [48]. Taken together, our observations demonstrate that D1 enhancer activity relies on the clustering of duplicate short conserved sequences.

Ci-Otx affects D1 enhancer activity

Among D1(ab) essential putative binding sites, the GATTA/TAATC “O” sequences correspond to the consensus for K50-Paired homeodomain proteins. In ascidians, this family includes Goosecoid, Pitx and Otx. Only Otx, is expressed in the right time and place to account for D1 enhancer activation in the anterior neuroectoderm in Ciona [20] and there is only one Otx gene in the Ciona intestinalis genome.

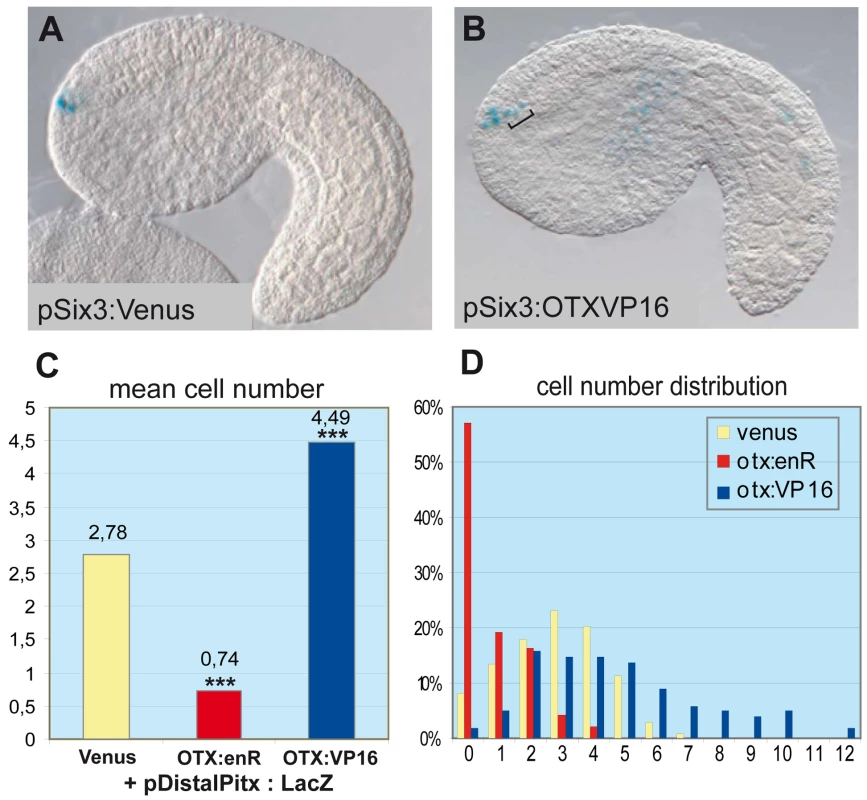

A functional study using morpholino antisense oligonucleotides in Halocynthia roretzi - another ascidian species - showed that the Hr-Otx knockdown strongly perturbs anterior neuroectoderm development, mostly because it is required for early specification events in the gastrula [49]. To avoid this early effect, we used targeted expression of dominant-negative and hyper-active versions of the Ci-OTX protein to interfere with its endogenous activity specifically after gastrulation. We thus engineered protein chimeras between the Ci-OTX homeodomain and the Drosophila engrailed repressor peptide or the VP16 trans-activation domain to create dominant-negative (OTX:EnR) or hyper-active (OTX:VP16) forms, respectively. We then used the Ci-Six3 cis-regulatory DNA to drive expression of these fusion proteins in a region that encompasses the ANB (Figure S1). These constructs were co-electroporated with the Ci-Distal-Pitx reporter plasmid, which contains the D1 enhancer with the two essential O1 and O2 K50-Paired binding sites [36], and the number of anterior neuroectodermal cells expressing the reporter gene was scored at the mid-tailbud stage (Figure 3). In control embryos expressing a Ci-Six3:Venus construct, an average of 2.78 anterior neuroectodermal cells per embryo activated the Ci-Pitx reporter construct, which can be accounted for by the mosaic incorporation of the transgene in the four ANB cells (Figure 3A and 3C). In contrast, targeted expression of Ci-OTX fusion proteins significantly altered Ci-Pitx reporter gene expression in the anterior neuroectoderm: the engrailed fusion inhibited ANB expression, while OTX:VP16 produced ectopic activation in surrounding neuroectodermal cells (Figure 3B–3D). Notably, OTX:VP16 also boosts expression of the ab dimer construct, and is not sufficient to induce overexpression when coelectroporated with one dimer construct bearing one O mutation (data not shown). This indicates that OTX:VP16 indeed binds to the GATTA binding sites. These observations strongly suggest that Ci-OTX trans-activating inputs are required for D1 enhancer activity in the anterior neuroectoderm. In addition, widespread expression of Ci-Otx in the anterior neuroectoderm contributes to the broad D1 trans-activation potential that encompasses the ANB, anterior epidermis and anterior sensory vesicle and is probably defined in D1 by the conserved GATTA/TAATC duplicated sequences. We cannot exclude the possibility that endogenous Ci-Pitx maintains its own expression through the same GATTA/TAATC BS, which binds PITX as well as OTX proteins. However, Otx is the best candidate for the onset of D1 activity, which begins exactly at the same time as the onset of the endogenous Ci-Pitx expression.

Fig. 3. OTX fusions influence the activity of the Ci-pitx cis-regulatory element.

Co-electroporation of Pitx full length distal region (pDistalPitx:lacZ, 5.3kb, containing D1), respectively with pSix3:Venus (control), with pSix3>OTXHD::enR (dominant negative OTX) and pSix3>OTXHD::VP16 (hyper-active OTX). (A) Side view of an embryo co-electroporated with pDistalPitx:lacZ and pSix3:Venus. Three positive cells can be detected in the ANB. (B) Co-electroporation of pDistalPitx:lacZ and pSix3>OTXHD::VP16. In addition to the expression in the ANB, ectopic expression is detected in the ASV cells (bracket) where OTX:VP16 is produced under the control of pSix3. (C) Numbers of lacZ expressing cells decrease with the OTXHD::enR protein (2.78 to 0.74 cells) and increase with the OTXHD::VP16 protein (2.78 to 4.49 cells) The distributions differ significantly from the control in both groups according to two Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney two-sample rank-sum tests: Control/OTXenR (UOTXenR = 3891, n(emb)OTXenR = 139, n(emb)ctrl = 131, P = 2.536e-07 two-tailed) and control/OTXVP16 (UOTXVP16 = 15582.5, n(emb)OTXVP16 = 98, nctrl = 131, P<2.2e-16 two-tailed). (D) Distributions of cell numbers in the ANB and ASV after co-electroporation of DistalPitx:lacZ and OTX fusions (yellow: control, red: enR fusion, blue: VP16 fusion; X-axis: cell numbers, Y-axis: proportions of embryos). Each experiment has been performed twice. Tandems of OTX binding sites preferentially flank anterior neuroectodermal and ectodermal genes

Of the three different duplicated BS that we identified for the ANB expression domain of Pitx and that we suppose to be specific to this restricted area of the anterior neuroectoderm, we concentrated our effort only on the binding sites for OTX as these are the only ones assignable to a well-characterized transcription factor. The observation that the transcriptional response to the broadly expressed head field-selector gene Otx is mediated by duplicated GATTA motifs led us to investigate whether this regulatory architecture was overrepresented in candidate Otx target genes in early tailbud embryos. At this stage, Ci-Otx expression extends over a broad domain referred to as in the anterior neuroectoderm, which derives from the a-line blastomeres and encompasses the ANB as well as other specific neurectodermal territories such as the anterior sensory vesicle, palps, a-line epidermis and rostral trunk epidermal neurons (RTEN). Therefore, we reasoned that candidate Otx target genes could, in principle, be expressed in all or part of the anterior neurectoderm. Hence, we asked whether duplicated GATTA motifs –the candidate signature for Otx binding - were enriched in the conserved noncoding sequences flanking genes with conspicuous expression in the anterior neurectoderm.

To this end, we obtained whole mount in situ hybridization data for 1518 genes showing tissue-specific expression from the model organism database ANISEED (December 2007, http://crfb.univ-mrs.fr/aniseed, see also Protocol S1). From these, we selected genes that are expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) and the ANB and classified them into different territories according to their expression along the antero-posterior axis: following previous reports [49]–[51], the ascidian visceral ganglion and the nerve cord were considered as “posterior” CNS whereas the whole sensory vesicle, including the ANB, constitute the “anterior” nervous system. This lead to a detailed annotation of nervous system expression patterns for 258 genes (Table S2). From this list we retained only those 100 genes that are specifically expressed in the anterior and not the posterior parts of the CNS. Finally, we obtained annotations for additional genes expressed in tissues like muscle, epidermis or notochord, from the database ANISEED. This latter set of genes was used as negative controls, which allowed for background definition for further statistical analyses. In total, our set includes annotations for 904 genes.

We then aimed at studying the distribution of duplicated short DNA motifs around these 904 genes to find those that show a bias towards genes expressed in the anterior or posterior nervous system, muscle, epidermis or notochord. We concentrated on conserved non-coding elements (CNEs), as these have been shown to be enriched in developmental enhancers [52], [53]. To obtain these elements for the genome of Ciona intestinalis, we created a whole-genome alignment with Ciona savignyi [54] and removed aligned positions in transcribed regions from it. This results in 168306 CNEs with an average length of 143 bp.

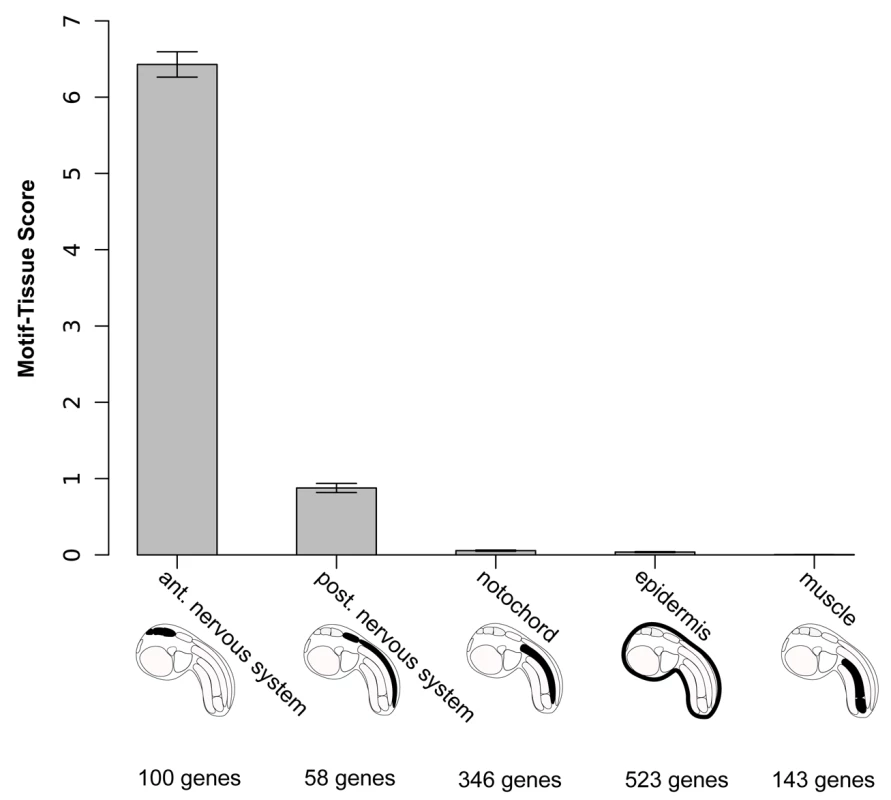

Then, we searched for duplicate matches to all 512 possible pentamers within 125 bp of all CNEs in the Ciona intestinalis genome and subsequently calculated the number of tissue-specific neighboring genes associated to each duplicated conserved pentamer and tissue. The rationale for using consensus and not matrix-based searches was that all subclasses of homeodomain proteins have well characterized binding sites that resemble pentamer motifs without degenerate positions [25], [26]. For the window size parameter, we observed from our case study that the sites had to occur in duplicates with a maximum distance of about 125bp, which was the total length of the fragment between both OTX-sites in the 75bp spacer construct. The score we chose was inspired by [55]; it does not require a sequence background model. This “motif-tissue-score” is the negative logarithm of the binomial probability to obtain a certain number of annotated genes from a given tissue by chance and therefore reflects the association of individual pentamer motifs with specific tissues.

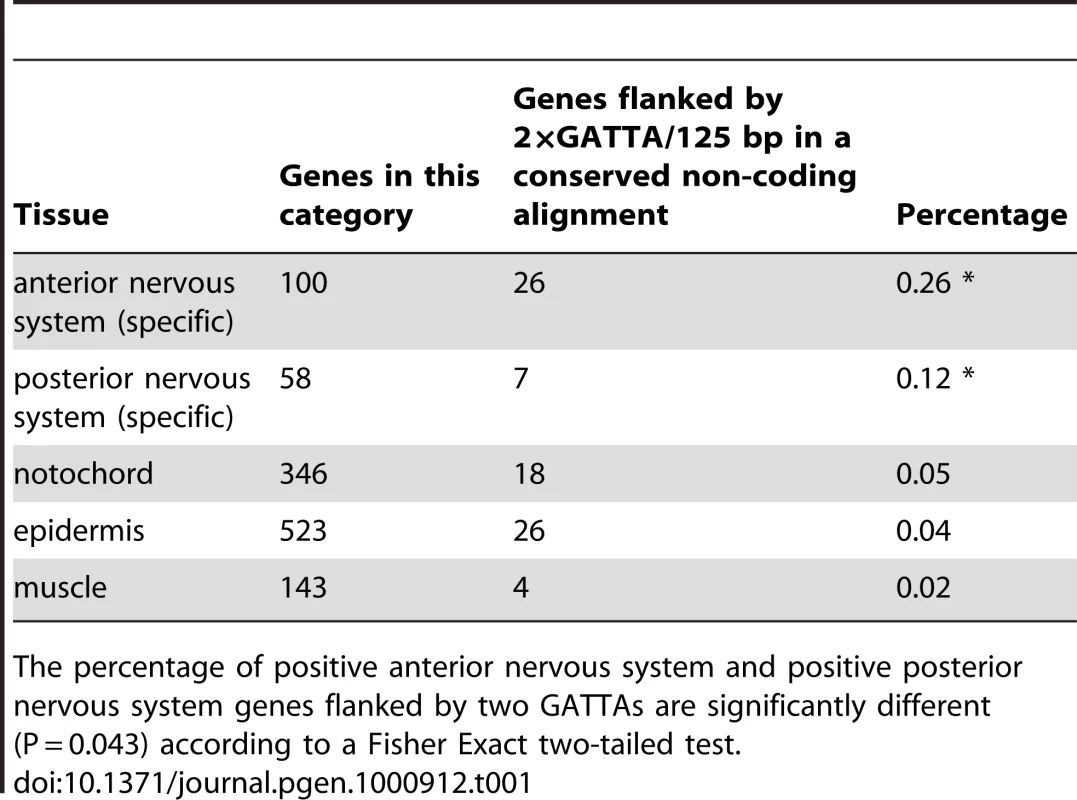

Our first observation was that a duplicated OTX (GATTA) motif within 125 basepairs appears among the motifs with the highest score in the anterior CNS region (Table S3). For instance, genes containing duplicated GATTA motifs within 125bp in their flanking conserved genomic DNA are more likely to be expressed in the anterior nervous system than in any of the other tissues used in this analysis, including the posterior CNS (26% versus 12% or less, Table 1).

Tab. 1. Antero-posterior distribution of enhancers with 2×GATTA tags.

The percentage of positive anterior nervous system and positive posterior nervous system genes flanked by two GATTAs are significantly different (P = 0.043) according to a Fisher Exact two-tailed test. We then set out to assess the robustness of this analysis to variations of all three parameters: copy-number, window size and gene annotation. We varied the number of motif-duplicates from one to four and still obtained the highest motif-tissue scores in the anterior region with two copies. Increasing the window size from 25bp to 300bp did not change the scores to a large extent and the relative order between the anterior nervous system and other tissues always remained the same (Figure S3). The influence of errors in the manual annotation process was investigated by a simulation: we randomized 10% of all gene annotations and repeated this procedure 100 times. The 95% confidence intervals from these are small compared to the total differences between the tissues (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Motif-tissue scores for the motif 2×GATTA/125bp against genes expressed in various tissues.

These territories are also visualized on schematic representation of an ascidian tailbud embryo. The number of genes is indicated for each category. To illustrate that changes in gene annotation are very unlikely to affect the overall ranking, we shuffled 10% of the gene-tissue assignments, repeated the procedure 100 times and plotted 95%-confidence intervals with error bars. These results indicate that a biased distribution of GATTA motifs in CNEs supports the model of anterior ectodermal expression based on D1 enhancer analysis. We conclude that the presence of duplicated and conserved OTX binding sites in a cis-regulatory element is a signature for anterior neuroectoderm enhancer activity.

Duplicated GATTA–motifs identify functional anterior ectoderm enhancers

We then sought to test whether conserved sequences containing duplicated GATTA motifs act as enhancers in the anterior neuroectoderm. Out of all 53 CNEs with at least two conserved GATTAs in a 125 bp window that flank genes expressed in the anterior nervous system, we selected 30 CNEs. We succeeded in cloning 23 of them into a lacZ expression vector. After electroporation, we observed that ten of them are active enhancers in various domains of the anterior neuroectoderm derivatives, where Otx is expressed at the tailbud stage (Figure 5, Figure S2, and Table S4). The remaining non-coding regions were inactive or drove non-specific expression in the mesenchyme, as is often observed in electroporated ascidian embryos [56], [57]. This ratio of positive elements is high compared to a previously published enhancer screen of random DNA fragments (5 active enhancers out of 138 tested fragments) [57] and similar to a prediction based on binding site occurrences in Drosophila muscle founder cells (6 out of 12 tested elements) [58].

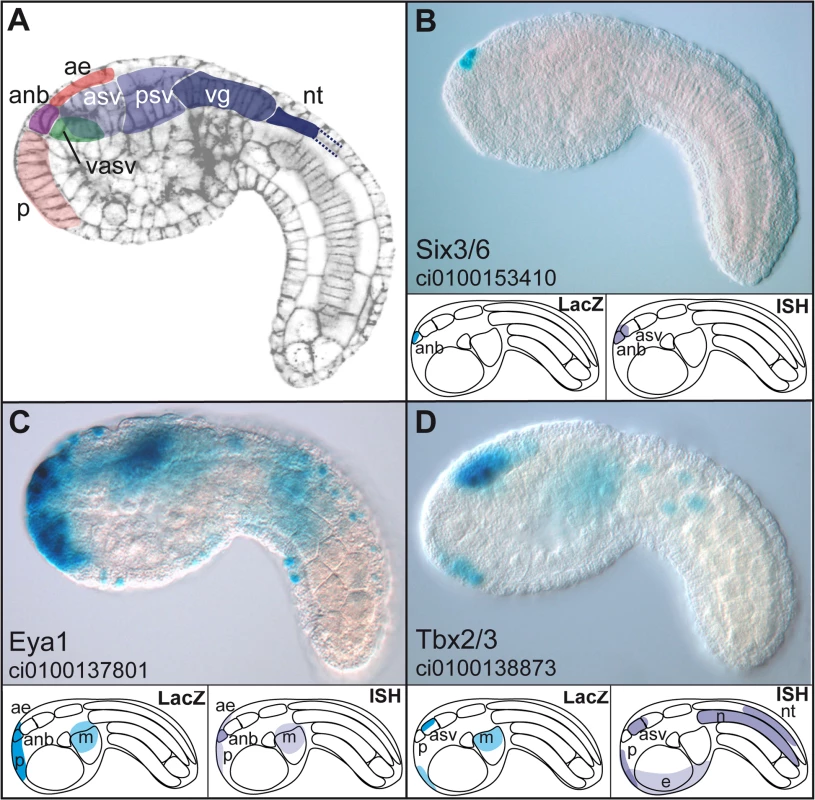

Fig. 5. Enhancers with duplicated GATTA are active in the anterior region of the ascidian embryo.

(A) Schematic representation of the main regions of gene expression in a mid-tailbud Ciona intestinalis embryo. Cell cortices are stained with Alexa-phalloidin (Christiaen et al. 2007). (B–D): expression domains of three enhancers, respectively from Ci-Six3/6, Ci-Eya1 and Ci-Tbx3 after electroporation and X-Gal staining at mid-tailbud stage. Lower panels show a schematic representation of the LacZ expression driven by the enhancer (left) and endogenous gene expression as assayed by in situ hybridization (ISH) (right). Enhancers can be subdivided into different classes following their expression domains: very restricted expression only in the ANB while the gene expression domain is slightly larger (Six3, (B)); broad anterior expression recapitulating more or less the endogenous expression pattern (Eya, (C)); only the most anterior expression domains are driven by the enhancer (Tbx3 (D)). anb: anterior neural boundary, asv: anterior sensory vesicle, psv: posterior sensory vesicle, vg: visceral ganglion, nt: neural tube, ae: anterior epidermis (or epineural epidermis), p: palps (precursors), m: mesenchyme, n: notochord. Lateral views, anterior to the left. We were unable to identify additional motifs that would be predictive of enhancer activity in the anterior neurectoderm (Figure S4). However, additional motifs are required in natural enhancers, as we showed that pentamers of GATTA alone were unable to drive reporter gene activity in the Otx expression domain (data not shown). The diversity of expression patterns obtained with the ten active enhancers rather suggests that different transcription factors, each specific for a subdomain of the anterior neuroectoderm, might be implied in the activity of these elements.

Thus, while there might be additional motifs necessary for anterior neuroectoderm expression, this study shows the importance of the duplicated GATTA regulatory architecture as a predictive tag for the identification of anterior enhancers in chordates.

Could a signature based on GATTA-sites also be predictive in vertebrates? [52] reported that GATTA is over-represented in forebrain enhancers and used it as one of six motifs to predict forebrain enhancers in the mouse genome. We also found other overrepresented motifs in anteriorly expressed genes (see Table S3). Therefore, as determined experimentally with the D1 element, additional complexity must supplement the duplicated GATTA sites to achieve a cell-specific expression. Similar approaches performed in Drosophila and Caenorhabditis have identified several binding sites, which correspond to factors that specify a particular fate or behaviour in a combinatorial fashion, such as the myogenic factors [58],[59]. However, our study identifies for the first time a cis-regulatory signature that determines the transcriptional response to a “master” homeobox gene in a simple chordate and establishes a model for genome-wide predictions of tissue-specific enhancers.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult Ciona intestinalis were purchased at the Station de Biologie Marine de Roscoff (France) and maintained in artificial sea water at 15°C under constant illumination. Eggs and sperm were collected from dissected gonads and used in cross fertilizations. Electroporations, using 70 µg of DNA, and LacZ stainings were performed as previously described [36]. Embryo staging at 13°C were done according to [60], [61]. Images were taken on a Leica DMR microscope.

Mutations in D1bcde

For the mutational analysis of the enhancer D1bcde (Figure 1), we omitted the first 16 bp (AAACGCGACGACCTCC) of D1abcde that were not conserved between Ciona intestinalis and savignyi. Each of the mutations was designed to perturb DNA-binding of the candidate trans-acting factors following various reports in the literature. Mutations were performed using the Stratagene QuickChange Kit. Seven new constructs called m0, m1, m2, m3, m4, m5/6, m7/8/9 were generated. After each electroporation, we observed LacZ expression in the tissues of the anterior neural boundary, anterior epidermis, ventro-anterior sensory vesicle and mesenchyme. We obtained a semi-quantitative estimation of the promoter activity by calculating the percentage of positive embryos.

Artificial enhancers

Plasmids with artificial enhancers were designed by cloning inserts into the pCES2::lacZ vector that contains the basal Ci-Fkh/FoxA promoter [57]. Insert D1(ab) was generated by cloning two long complementary primers with XhoI/XbaI cohesive ends into pCES2. Inserts (abde), (abd), (ab)(ab-Pdel), (ab)(ab-Omut), (ab)(ab-Tmut), (ab)(ab-Gmut) were generated by cloning a second insert consisting of another couple of long complementary primers into the XbaI/BamHI site of D1(ab). The insert of D1(ab)×5 was designed in silico, synthetized by Genecust Europe (Luxembourg) and cloned into pCES2::LacZ between XhoI and BamHI. To obtain D1(ab)(ab), we cut out the first two parts of D1(ab)×5 with SalI/XhoI and ligated them into pCES2.

The spacer sequence between both (ab) parts of D1(ab)-xx-(ab) constructs was created in silico by avoiding all octamers bound by homeodomain factors from a large-scale DNA-protein binding assay [25]. We recursively added random nucleotides to an unbound sequence and backtracked if the new sequence contained an octamer with PBM enrichment score >0.3 from the UniProbe database [62]. These constructs, D1(ab)-xx-(ab) are also derived from D1(ab), but the insert was synthesized by GeneScript Corporation (Piscatway, NJ, USA). We amplified spacers of the appropriate length by PCR from the longer fragment and cloned them between the two duplicated (ab) fragment by restriction/ligation.

OTX fusions

A pSix3:Venus plasmid was digested by BamHI/EcoRI to eliminate the Venus/YFP reporter.

VP16 fusion

the OTXHD fragment was amplified by PCR from tailbud Ciona cDNA using OTXHD-F (CGGGATCCACAATGGTATACAGTTCGTCTAGAAAA) and OTXHD-R (AAACCATGGGTTGTTGCACTTGTTGGCGACA) oligos and digested by BamHI/NcoI. The VP16 domain was amplified with VP16-F (AAGATATCGACAAACCATGGTGCAGCTGGCACCACCGACCGATGTCAG) and VP16-R (AACAGCTGGAATTCTTAGATATCCCCACCGTACTCGTCAATTC) oligos, and digested by NcoI/EcoRI. Both resulting fragments were ligated into the linearized pSix3 driver to obtain the pSix3:OTXHD:VP16 construct.

EnR fusion

the OTXHD fragment was amplified by PCR from tailbud cDNA using OTXHD-F (CGGGATCCACAATGGTATACAGTTCGTCTAGAAAA) and OTXHD-R (AAACCATGGGTTGTTGCACTTGTTGGCGACA) oligos. The enR repressor domain was amplified with enR-F (CTCGAGGCCCTGGAGGATCGC) and enR-R (CGAATTCTATACGTTCAGGTCCT) oligos. Both fragments were fused by additionnal rounds of PCR using oligos that overlap the 3′ part of OTXHD and the 5′ part of enR (enR(OTX)F:TGTCGCCAACAAGTGCAACAACTCGAGGCCCTGGAGGATCGC, OTXHD(enR) R: GCGATCCTCCAGGGCCTCGAGTTGTTGCACTTGTTGGCGACA). The resulting product was digested by BamHI/EcoRI and ligated into into the digested pSix3 driver to obtain the pSix3: OTXHD:enR construct.

Constructs for the enhancer screen

Plasmids containing non-coding elements were created with the Gateway Technology System (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA, USA). We cloned an AttR3/AttR4 Gateway Cassette from [63] into the XhoI/XbaI-site of pCES2 and called the resulting construct AttR3R4-pCES2. Predicted fragments were first amplified by primers including part of the flanking AttB3/AttB4-sequences and then extended by a subsequent PCR to the full length sequences of AttB3/AttB4. These fragments were recombined with BP clonase into the P3/P4-donor Vector [63] and the resulting entry vectors recombined with LR clonase into AttR3R4-pCES2 producing expression vectors.

In silico methods

Computational methods are described in Protocol S1. Programs that were used for whole-genome analyses are accessible at http://genome.ciona.cnrs-gif.fr/scripts/.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Garcia-BellidoA

1975 Genetic control of wing disc development in Drosophila. Ciba Found Symp 0 161 182

2. HobertO

2008 Regulatory logic of neuronal diversity: terminal selector genes and selector motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 20067 20071

3. BlackshawS

FraioliRE

FurukawaT

CepkoCL

2001 Comprehensive analysis of photoreceptor gene expression and the identification of candidate retinal disease genes. Cell 107 579 589

4. ChenS

WangQL

NieZ

SunH

LennonG

1997 Crx, a novel Otx-like paired-homeodomain protein, binds to and transactivates photoreceptor cell-specific genes. Neuron 19 1017 1030

5. HsiauTH

DiaconuC

MyersCA

LeeJ

CepkoCL

2007 The cis-regulatory logic of the mammalian photoreceptor transcriptional network. PLoS ONE 2 e643 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000643

6. AlonU

2007 Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nat Rev Genet 8 450 461

7. KoikeC

NishidaA

UenoS

SaitoH

SanukiR

2007 Functional roles of Otx2 transcription factor in postnatal mouse retinal development. Mol Cell Biol 27 8318 8329

8. NishidaA

FurukawaA

KoikeC

TanoY

AizawaS

2003 Otx2 homeobox gene controls retinal photoreceptor cell fate and pineal gland development. Nat Neurosci 6 1255 1263

9. RanadeSS

Yang-ZhouD

KongSW

McDonaldEC

CookTA

2008 Analysis of the Otd-dependent transcriptome supports the evolutionary conservation of CRX/OTX/OTD functions in flies and vertebrates. Dev Biol 315 521 534

10. TahayatoA

SonnevilleR

PichaudF

WernetMF

PapatsenkoD

2003 Otd/Crx, a dual regulator for the specification of ommatidia subtypes in the Drosophila retina. Dev Cell 5 391 402

11. McDonaldJA

FujiokaM

OddenJP

JaynesJB

DoeCQ

2003 Specification of motoneuron fate in Drosophila: integration of positive and negative transcription factor inputs by a minimal eve enhancer. J Neurobiol 57 193 203

12. WenickAS

HobertO

2004 Genomic cis-regulatory architecture and trans-acting regulators of a single interneuron-specific gene battery in C. elegans. Dev Cell 6 757 770

13. HongJW

HendrixDA

PapatsenkoD

LevineMS

2008 How the Dorsal gradient works: insights from postgenome technologies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 20072 20076

14. ZinzenRP

CandeJ

RonshaugenM

PapatsenkoD

LevineM

2006 Evolution of the ventral midline in insect embryos. Dev Cell 11 895 902

15. DenesAS

JekelyG

SteinmetzPR

RaibleF

SnymanH

2007 Molecular architecture of annelid nerve cord supports common origin of nervous system centralization in bilateria. Cell 129 277 288

16. ChioriR

JagerM

DenkerE

WinckerP

Da SilvaC

2009 Are Hox genes ancestrally involved in axial patterning? Evidence from the hydrozoan Clytia hemisphaerica (Cnidaria). PLoS ONE 4 e4231 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004231

17. DavidsonE

2006 The regulatory genome San Diego Academic

18. LoweCJ

WuM

SalicA

EvansL

LanderE

2003 Anteroposterior patterning in hemichordates and the origins of the chordate nervous system. Cell 113 853 865

19. BruceAE

ShanklandM

1998 Expression of the head gene Lox22-Otx in the leech Helobdella and the origin of the bilaterian body plan. Developmental biology 201 101 112

20. HudsonC

LemaireP

2001 Induction of anterior neural fates in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Mechanisms of development 100 189 203

21. WilliamsN

HollandP

1996 Old head on young shoulders. Nature 383 490 490

22. SchlosserG

2006 Induction and specification of cranial placodes. Developmental Biology 294 303 351

23. AcamporaD

MazanS

LallemandY

AvantaggiatoV

MauryM

1995 Forebrain and midbrain regions are deleted in Otx2−/ − mutants due to a defective anterior neuroectoderm specification during gastrulation. Development (Cambridge, England) 121 3279 3290

24. AcamporaD

GulisanoM

BroccoliV

SimeoneA

2001 Otx genes in brain morphogenesis. Progress in neurobiology 64 69 95

25. BergerMF

BadisG

GehrkeAR

TalukderS

PhilippakisAA

2008 Variation in homeodomain DNA binding revealed by high-resolution analysis of sequence preferences. Cell 133 1266 1276

26. NoyesMB

ChristensenRG

WakabayashiA

StormoGD

BrodskyMH

2008 Analysis of homeodomain specificities allows the family-wide prediction of preferred recognition sites. Cell 133 1277 1289

27. HanesSD

BrentR

1991 A genetic model for interaction of the homeodomain recognition helix with DNA. Science (New York, NY) 251 426 430

28. AcamporaD

AvantaggiatoV

TuortoF

BaroneP

PereraM

1999 Differential transcriptional control as the major molecular event in generating Otx1−/ − and Otx2−/ − divergent phenotypes. Development (Cambridge, England) 126 1417 1426

29. AcamporaD

AvantaggiatoV

TuortoF

BaroneP

ReichertH

1998 Murine Otx1 and Drosophila otd genes share conserved genetic functions required in invertebrate and vertebrate brain development. Development (Cambridge, England) 125 1691 1702

30. AdachiY

NagaoT

SaigaH

Furukubo-TokunagaK

2001 Cross-phylum regulatory potential of the ascidian Otx gene in brain development in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Genes Evol 211 269 280

31. WadaH

SaigaH

SatohN

HollandPW

1998 Tripartite organization of the ancestral chordate brain and the antiquity of placodes: insights from ascidian Pax-2/5/8, Hox and Otx genes. Development 125 1113 1122

32. SatohN

LevineM

2005 Surfing with the tunicates into the post-genome era. Genes Dev 19 2407 2411

33. ImaiKS

HinoK

YagiK

SatohN

SatouY

2004 Gene expression profiles of transcription factors and signaling molecules in the ascidian embryo: towards a comprehensive understanding of gene networks. Development 131 4047 4058

34. SatouY

TakatoriN

YamadaL

MochizukiY

HamaguchiM

2001 Gene expression profiles in Ciona intestinalis tailbud embryos. Development 128 2893 2904

35. TassyO

DaianF

HudsonC

BertrandV

LemaireP

2006 A quantitative approach to the study of cell shapes and interactions during early chordate embryogenesis. Curr Biol 16 345 358

36. ChristiaenL

BourratF

JolyJS

2005 A modular cis-regulatory system controls isoform-specific pitx expression in ascidian stomodaeum. Dev Biol 277 557 566

37. BoormanCJ

ShimeldSM

2002 Pitx homeobox genes in Ciona and amphioxus show left-right asymmetry is a conserved chordate character and define the ascidian adenohypophysis. Evol Dev 4 354 365

38. ChristiaenL

BurighelP

SmithWC

VernierP

BourratF

2002 Pitx genes in Tunicates provide new molecular insight into the evolutionary origin of pituitary. Gene 287 107 113

39. BertrandV

HudsonC

CaillolD

PopoviciC

LemaireP

2003 Neural tissue in ascidian embryos is induced by FGF9/16/20, acting via a combination of maternal GATA and Ets transcription factors. Cell 115 615 627

40. BryneJC

ValenE

TangMH

MarstrandT

WintherO

2008 JASPAR, the open access database of transcription factor-binding profiles: new content and tools in the 2008 update. Nucleic Acids Res 36 D102 106

41. MatysV

FrickeE

GeffersR

GosslingE

HaubrockM

2003 TRANSFAC: transcriptional regulation, from patterns to profiles. Nucleic Acids Res 31 374 378

42. LebrechtD

FoehrM

SmithE

LopesFJ

Vanario-AlonsoCE

2005 Bicoid cooperative DNA binding is critical for embryonic patterning in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 13176 13181

43. ArnoneMI

DavidsonEH

1997 The hardwiring of development: organization and function of genomic regulatory systems. Development 124 1851 1864

44. FuD

ZhaoC

MaJ

2003 Enhancer sequences influence the role of the amino-terminal domain of bicoid in transcription. Molecular and cellular biology 23 4439 4448

45. MaX

YuanD

DiepoldK

ScarboroughT

MaJ

1996 The Drosophila morphogenetic protein Bicoid binds DNA cooperatively. Development 122 1195 1206

46. HareEE

PetersonBK

EisenMB

2008 A careful look at binding site reorganization in the even-skipped enhancers of Drosophila and sepsids. PLoS Genet 4 e1000268 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000268

47. OndekB

GlossL

HerrW

1988 The SV40 enhancer contains two distinct levels of organization. Nature 333 40 45

48. FriedmanAM

FischmannTO

SteitzTA

1995 Crystal structure of lac repressor core tetramer and its implications for DNA looping. Science 268 1721 1727

49. WadaS

SudouN

SaigaH

2004 Roles of Hroth, the ascidian otx gene, in the differentiation of the brain (sensory vesicle) and anterior trunk epidermis in the larval development of Halocynthia roretzi. Mechanisms of development 121 463 474

50. DufourHD

ChettouhZ

DeytsC

de RosaR

GoridisC

2006 Precraniate origin of cranial motoneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 8727 8732

51. ImaiKS

SatohN

SatouY

2002 Region specific gene expressions in the central nervous system of the ascidian embryo. Mech Dev 119 Suppl 1 S275 277

52. PennacchioL

AhituvN

MosesA

PrabhakarS

NobregaM

2006 In vivo enhancer analysis of human conserved non-coding sequences. Nature

53. WoolfeA

GoodsonM

GoodeDK

SnellP

McEwenGK

2005 Highly conserved non-coding sequences are associated with vertebrate development. PLoS Biol 3 e7 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030007

54. KentWJ

BaertschR

HinrichsA

MillerW

HausslerD

2003 Evolution's cauldron: duplication, deletion, and rearrangement in the mouse and human genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 11484 11489

55. Yoseph BarashGB

FriedmanNir

Moret OGaBME, ed. Algorithms in Bioinformatics, First International Workshop, WABI 2001, Aarhus, Denmark, August 28–31, 2001, Proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; 2001 2001; Aarhus, Denmark Springer 278 293

56. CorboJC

LevineM

ZellerRW

1997 Characterization of a notochord-specific enhancer from the Brachyury promoter region of the ascidian, Ciona intestinalis. Development 124 589 602

57. HarafujiN

KeysDN

LevineM

2002 Genome-wide identification of tissue-specific enhancers in the Ciona tadpole. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 6802 6805

58. PhilippakisA

BusserB

GisselbrechtS

HeF

EstradaB

2006 Expression-Guided In Silico Evaluation of Candidate Cis Regulatory Codes for Drosophila Muscle Founder Cells. PLoS Comput Biol 2 e53 doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020053

59. HalfonMS

GradY

ChurchGM

MichelsonAM

2002 Computation-based discovery of related transcriptional regulatory modules and motifs using an experimentally validated combinatorial model. Genome Res 12 1019 1028

60. ChristiaenL

JaszczyszynY

KerfantM

KanoS

ThermesV

2007 Evolutionary modification of mouth position in deuterostomes. Semin Cell Dev Biol 18 502 511

61. HottaK

MitsuharaK

TakahashiH

InabaK

OkaK

2007 A web-based interactive developmental table for the ascidian Ciona intestinalis, including 3D real-image embryo reconstructions: I. From fertilized egg to hatching larva. Dev Dyn 236 1790 1805

62. NewburgerDE

BulykML

2009 UniPROBE: an online database of protein binding microarray data on protein-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 37 D77 82

63. RoureA

RothbacherU

RobinF

KalmarE

FeroneG

2007 A multicassette Gateway vector set for high throughput and comparative analyses in ciona and vertebrate embryos. PLoS ONE 2 e916 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000916

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 4- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Whole-Genome SNP Association in the Horse: Identification of a Deletion in Myosin Va Responsible for Lavender Foal Syndrome

- Human Telomeres Are Hypersensitive to UV-Induced DNA Damage and Refractory to Repair

- Fragilities Caused by Dosage Imbalance in Regulation of the Budding Yeast Cell Cycle

- Admixture Mapping Scans Identify a Locus Affecting Retinal Vascular Caliber in Hypertensive African Americans: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study

- Activation of Estrogen-Responsive Genes Does Not Require Their Nuclear Co-Localization

- Genetic Tests for Ecological and Allopatric Speciation in Anoles on an Island Archipelago

- A Pax3/Dmrt2/Myf5 Regulatory Cascade Functions at the Onset of Myogenesis

- Two New Loci for Body-Weight Regulation Identified in a Joint Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies for Early-Onset Extreme Obesity in French and German Study Groups

- Hypomethylation of a LINE-1 Promoter Activates an Alternate Transcript of the MET Oncogene in Bladders with Cancer

- Candidate Causal Regulatory Effects by Integration of Expression QTLs with Complex Trait Genetic Associations

- Combined Inactivation of pRB and Hippo Pathways Induces Dedifferentiation in the Retina

- Allele-Specific Virulence Attenuation of the HopZ1a Type III Effector via the ZAR1 Resistance Protein

- Down-Regulation of Honey Bee Gene Biases Behavior toward Food Rich in Protein

- A Microarray-Based Genetic Screen for Yeast Chronological Aging Factors

- Actin-Related Protein Arp6 Influences H2A.Z-Dependent and -Independent Gene Expression and Links Ribosomal Protein Genes to Nuclear Pores

- Phosphorylation of the Conserved Transcription Factor ATF-7 by PMK-1 p38 MAPK Regulates Innate Immunity in

- A -Regulatory Signature for Chordate Anterior Neuroectodermal Genes

- Genetic Analysis of Fin Development in Zebrafish Identifies Furin and Hemicentin1 as Potential Novel Fraser Syndrome Disease Genes

- Assembly of a 40 Mb Eukaryotic Genome from Short Sequence Reads: , a Model Organism for Fungal Morphogenesis

- Trait-Associated SNPs Are More Likely to Be eQTLs: Annotation to Enhance Discovery from GWAS

- Absence of Evidence for MHC–Dependent Mate Selection within HapMap Populations

- The TALE Class Homeobox Gene Defines the Anterior Compartment for Head Regeneration

- Cyclic Expression of Lhx2 Regulates Hair Formation

- Genetic Evidence for Hybrid Trait Speciation in Butterflies

- Epigenetic Regulation of a Murine Retrotransposon by a Dual Histone Modification Mark

- Chromosome 9p21 SNPs Associated with Multiple Disease Phenotypes Correlate with Expression

- S Phase Progression in Human Cells Is Dictated by the Genetic Continuity of DNA Foci

- The Next Generation Becomes the Now Generation

- Acts as a Tumor Suppressor in a Murine Retinoblastoma Model by Facilitating Tumor Cell Death

- Genome-Wide Association Study of Lp-PLA Activity and Mass in the Framingham Heart Study

- The Five Zinc Transporters Undergo Different Evolutionary Fates towards Adaptive Evolution to Zinc Tolerance in

- MicroRNA–Directed siRNA Biogenesis in

- Deletion of the WD40 Domain of LRRK2 in Zebrafish Causes Parkinsonism-Like Loss of Neurons and Locomotive Defect

- Incipient Balancing Selection through Adaptive Loss of Aquaporins in Natural Populations

- GTPase Activity Plays a Key Role in the Pathobiology of LRRK2

- Natural Single-Nucleosome Epi-Polymorphisms in Yeast

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Whole-Genome SNP Association in the Horse: Identification of a Deletion in Myosin Va Responsible for Lavender Foal Syndrome

- Admixture Mapping Scans Identify a Locus Affecting Retinal Vascular Caliber in Hypertensive African Americans: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study

- Genetic Tests for Ecological and Allopatric Speciation in Anoles on an Island Archipelago

- Human Telomeres Are Hypersensitive to UV-Induced DNA Damage and Refractory to Repair

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání