-

Medical journals

- Career

Pseudotumors and mimickers of malignancy of the head and neck pathology

Authors: M. Michal; D. Kacerovská; D. V. Kazakov; A. Skálová

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Pathology, Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Medicine in Plzen, Czech Republic

Published in: Čes.-slov. Patol., 48, 2012, No. 4, p. 190-197

Category: Reviews Article

Overview

We are summarizing some of the difficult pitfalls in tumors of the head and neck, which we have encountered in our biopsies referred for consultation as well as from our routine praxis in the last 20 years. Shortly we are presenting the following lesions of head and neck: multifocal sclerosing thyroiditis, mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the thyroid, solid cell nests, Chievitz organ, rhomboid glossitis, ectopic parathyroid, signet ring cell change of salivary glands, mucocele, epithelial misplacement of the vocal cord squamous cell epithelium, and angiomatoid nasal polyps.

Keywords:

multifocal sclerosing thyroiditis – mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the thyroid –solid cell nests – Chievitz organ – rhomboid glossitis – ectopic parathyroid – signet ring cell change of salivary glands – mucocele – epithelial misplacement of the vocal cord squamous cell epithelium, angiomatoid nasal polypsHead and neck pathology represents one of the most difficult parts of the discipline, because it encompasses many different lesions in several organs including major and minor salivary gland pathology, thyroid lesions, specific soft tissue pseudotumors and tumors, lymphomas unique to this region and others. In addition, head and neck pathology includes various embryological aberrations not occurring elsewhere in the human body. Pathologists of Plzen laboratories have been receiving for many years consultations virtually from the whole world. During the last 20 years, we collectively obtained nearly 100.000 referral cases, and head and neck lesions represent an important bulk of this collection filed in our registries.

The diagnostic problems addressed in this paper are not chosen systematically, but rather haphazardly, with emphasis on histopathological changes that may represent a serious diagnostic pitfalls to the unwary and which we consider to be the most interesting and treacherous. Thus, the aim of this article is not to present a systematic clinicopathologic overview, but to draw attention to dangerous pitfalls which can be encountered by pathologists in this difficult diagnostic field and to provide our colleagues with a knowledge that would allow them to avoid diagnostic traps. In many cases, a mere awareness of the below described lesions that are often identifiable with the use of simple hematoxylin and eosin stains is helpful.

1. LESIONS OF MINOR SALIVARY GLANDS WITH NON-NEOPLASTIC SIGNET-RING CELLS

The term “signet-ring cells” is used to describe the round shaped cells with a crescent nucleus caused by its compression by accumulation of mucin in the cytoplasm. The nucleus is often dislodged at the periphery of the cells by the intracytoplasmic mucus. Traditionally, the signet-ring cells have been considered a hallmark of signet ring cell adenocarcinoma with a poor prognosis, most of which originate in the gastrointestinal tract, and the stomach in particular. There are, however, exceptions to this rule, and, rarely, these signet-ring cells have been described in various organs where they represented non-neoplastic lesions caused by inflammation or adjacent necrosis. Non-neoplastic signet-ring cells have been reported in the colon (1–4), salivary glands (5), cervix (6), gallbladder (2,6), gastrointestinal and biliary tract (7), prostate (8), urinary bladder (9), lymph nodes (10) and endometrium (11). In salivary glands, occurrence of epithelial non-neoplastic signet-ring cells is extremely rare (12). In contrast to metastatic signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma, in which malignant signet-ring cells grow diffusely demonstrating no relation to the preexisting structures, epithelial non-neoplastic signet-ring cells, albeit often seen in a dyscohesive manner are usually situated within the limits of the basal membrane of preexisting structures of salivary gland acini (Fig. 1A). Thus, occurrence of signet-ring cells within the confines of salivary gland acini structures may serve a clue to a non-neoplastic and benign nature of the pathologic process. There are, however, two more frequently encountered situations, in which signet-ring change may be seen outside the salivary gland and the signet-ring cells occur within the mesenchymal moiety of both types of the lesions. One of them represents a mucocele with a leakage of mucus into the surrounding stroma (Fig. 1B). In our experience, when the surgical material obtained from mucocele is fragmented, the surrounding stromal cells packed with epithelial mucicarmine stainable mucus can closely simulate metastatic adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1C). The other situation is occurrence of signet ring cells within the stroma, usually around minor salivary glands, without an apparent reason (Fig. 1D,E). The latter phenomenon probably represents a fixation artifact.

Fig. 1. A: Epithelial non-neoplastic signet-ring cells in a dyscohesive manner within the limits of the basal membrane of a preexisting salivary gland acini (magnification 400x). B: Mucocele with a spillage of the mucus into the surrounding tissues (40x). C: Stromal cells around mucocele are packed with epithelial mucicarmine stainable mucus and closely simulate a metastatic adenocarcinoma (200x). D, E: Signet-ring cell change within the stroma around salivary gland simulates a metastatic adenocarcinoma (20x and 400x, resp.).

2. PARATHYROID GLAND TISSUE MIMICKING CLEAR CELL CARCINOMAS

Minute foci of parathyroid gland tissue can infrequently be seen as small inclusions within the vagus nerve, especially in the rostral part of it. Such inclusions have been observed in 6 % of children (13) in the first year of life and 4 % (14) of the adult vagus nerves. They may simulate either vagus paraganglia or even inclusions of a metastatic clear cell carcinoma, especially from the kidney. In contrast to these minute clear cell parathyroid gland inclusions which are clinically unapparent and usually found incidentally on microscopic examination, metastatic renal clear cell carcinoma usually grows as a large mass that is easily detectable grossly. A case of parathyroid inclusions within the cervical ganglion (probably related to the vagus nerve) in a patient with papillary thyroid carcinoma has been described (15).

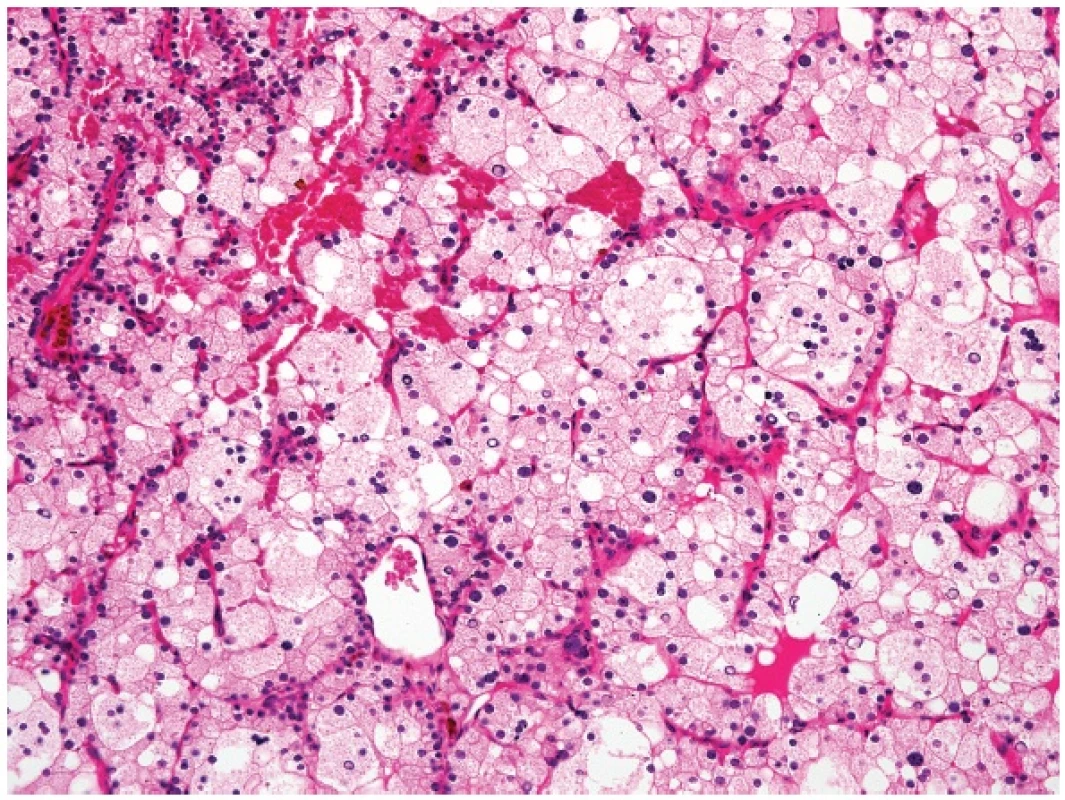

Another situation when parathyroid tissue may resemble a metastatic renal clear cell carcinoma is water-clear cell hyperplasia (WCCH) of the parathyroid gland (16) (Fig. 2). The confusion can be caused by the gross appearance of WCCH which, in contrast to other well-circumscribed parathyroid gland benign proliferations, may look worrisome, with pseudopods of typical brown chocolate color that may extend a considerable distance from the main mass of the parathyroid glands (17).

Immunohistochemical positivity to antibodies to parathormone, chromogranin and synaptophysin distinguishes WCCH from any metastatic renal clear cell carcinomas.

1. Water-clear cell hyperplasia of the parathyroid gland (magnification 200x).

3. HYPERPLASTIC SOLID CELL NESTS OF THE THYROID MIMICKING METASTATIC SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

Solid cell nests (SCNs) are remnants of the ultimobranchial body and can rarely undergo considerable hyperplasia as to occasion a resemblance to a metastatic squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 3A,B). In this context, SCNs can be distinguished from carcinoma by the p63 positivity, near lack of MIB1 positivity and frequent lymphotropism (18) (Fig. 3C). We have seen cases in which the hyperplasia of SCNs was so prominent so that it was difficult to be distinguished from well differentiated mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the thyroid gland (Fig. 3D-F). Such lesions usually arise on the background of Hashimoto thyroiditis. It is our empirical experience that the cases in which a pathologist cannot decide between hyperplastic SCNs and mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the thyroid the lesion will likely behave in a benign way.

Contrary to the literature reports stating that calcitonin positive cells are typically found in SCNs, in our experience no such cells can sometimes be seen in SCNs, especially in cases with atrophic changes in the surrounding thyroid gland parenchyma. In the extreme scenario, most of the thyroid parenchyma is atrophic (Fig. 3G), and hyperplastic SCNs may be surrounded by a branchial cleft cyst as the only structures left (19).

Fig. 3. Prominent hyperplasia of solid cell nests simulating a metastatic carcinoma (A, magnification 100x). Note, however a bland appearance without atypia and mitoses (B, 200x). Heavy lymphotropism in solid cell nests (C, 200x). D-F: Hyperplasia of SCNs which is difficult to be distinguished from well differentiated mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the thyroid. MIB1 antibody stained less than 1 % of the cells in this case. All figures are from the same case (40x, 100x and 200x, resp.). G: Atrophic thyroid parenchyma with hyperplastic solid cell nests (100x).

4. MULTIFOCAL SCLEROSING THYROIDITIS

Multifocal sclerosing thyroiditis is a little known and apparently underrecognized lesion described only in a short single case report in 2009 (20). Surprisingly, no clinicopathologic series has so far been published, given the fact that the lesion is not uncommon and certainly represents one of the greatest pitfalls in thyroid pathology. Poli et al. likened multifocal sclerosing thyroiditis to the radial scar of the mammary glands (20) (Fig. 4A,B.) and suggested that the lesion begins with a localized injury to the tissue (sometimes accompanied by identifiable necrosis) and is followed by desmoplastic stromal response, which leads to entrapment and reactive or compensatory hyperplasia of the epithelial elements (thyroid follicles). The authors further posited that in some instances this “reactive atypia” may proceed to the development of papillary (micro)carcinoma (20). In our experience, this lesion, in spite of being mostly multifocal, may also occur as a solitary lesion. In contrast to papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland, multifocal sclerosing thyroiditis is negative for CK19 (our unpublished observations) and its nuclear features differ from those seen in papillary carcinoma of the thyroid (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4. A: Configuration of sclerosing thyroiditis is similar to the radial scar of the mammary gland. B: Focus of sclerosing thyroiditis containing collagen and some elastic fibres. Van Gieson stain. C: A close-up view showing that the nuclei lack the cytologic features of papillary thyroid carcinoma (magnification 40x, 40x and 200x, resp.).

5. SEQUESTERED THYROID NODULE

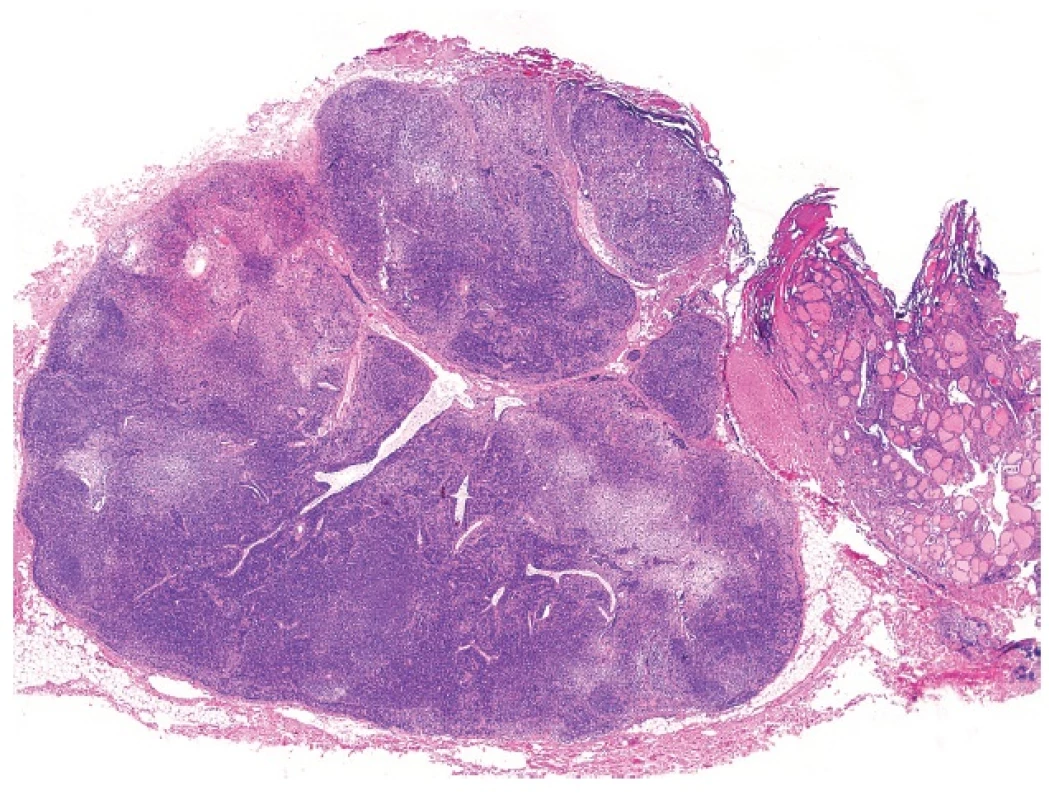

This phenomenon, also known as parasitic or accessory nodule, denotes the occurrence of a peripherally located thyroid nodule in which the anatomic connection to the main thyroid gland is lost or could not be identified by the surgeon. The nodule is usually an expression of nodular hyperplasia or nodular Hashimoto thyroiditis, less commonly of diffuse thyroidal hyperplasia (Graves disease) (21). Sequestered nodule is subject to the same morphologic alterations as is the main gland and this may cause significant interpretation problems, especially in Hashimoto thyroiditis, in which the combination of nuclear atypia and a heavy lymphoid infiltrate may result in the appearances closely simulating lymph nodal structures containing a metastatic tumor. Another problem may occur when a sequestered thyroid nodule is juxtaposed to a lymph node simulating a metastatic thyroidal carcinoma (Fig. 5).

2. Sequestered thyroidal nodule juxtaposed to a lymph node simulating a metastatic thyroid carcinoma (magnification 20x).

6. MEDIAN RHOMBOID GLOSSITIS

Median rhomboid glossitis (MRG) was described nearly a century ago; however, it appears that the lesion is still little known among pathologists. MRG affects males in 70–80 % of the cases. Its etiology is unknown, although it has been repeatedly proposed that the lesion may be caused by chronic candidiasis. There is a strong association with immunesuppression, particularly HIV (22) and there may be a localized immunologic defect in otherwise healthy individuals suffering from MRG (23). In spite of the fact that in most cases of MRG Candida albicans can be demonstrated morphologically or by culture tests, some patients with MRG have identical histological changes on the tongue without a demonstrable infection agent.

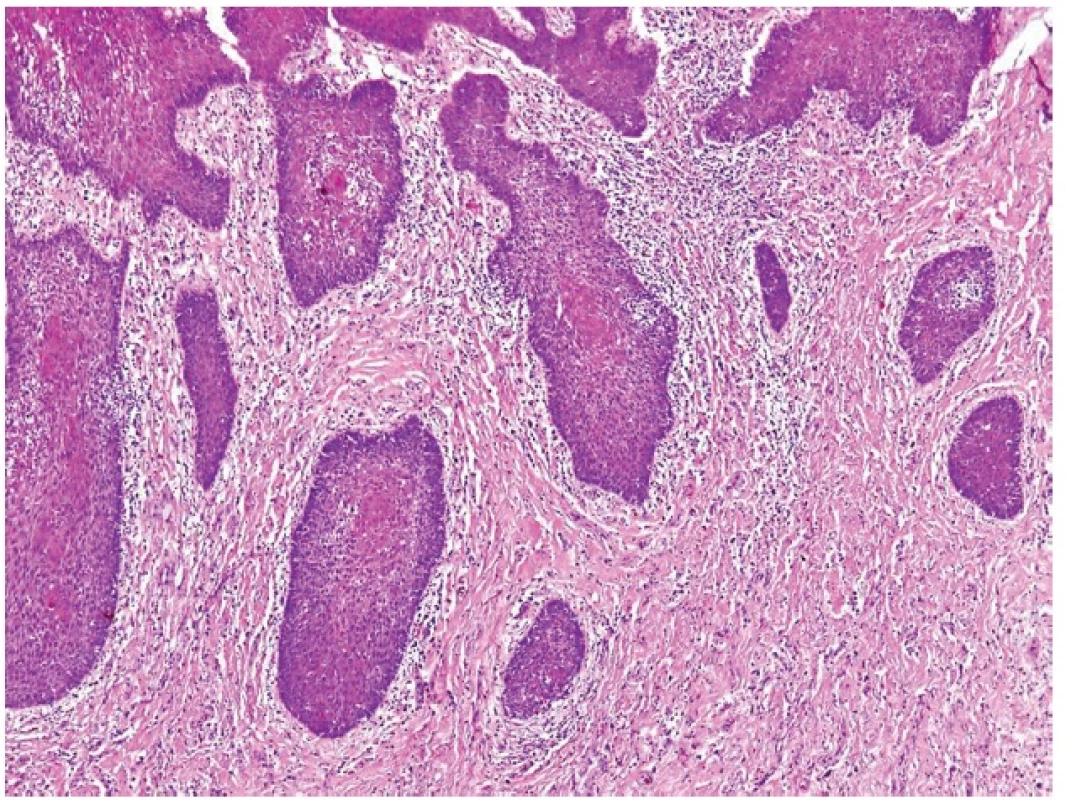

Usually, as the name implies, MRG involves the median parts of the tongue. However, MRG may sometimes be seen in atypical sites, especially in paramedian locations (24). Clinically, it presents as an indurated, erythematous lump on the dorsal midline of the tongue anterior to the foramen cecum (25). and may grossly simulate a carcinoma. Microscopically, MRG shows a loss of the normal surface papillations with underlying, complex squamous pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia simulating invasive well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 6). The neighbouring seromucinous glands may undergo squamous metaplasia (24). Awareness of the clinical features and lack of cytological atypia on histology allows the distinction from a malignant lesion. It should be born in mind that occurrence of squamous cell carcinoma in this precise lingual location is quite rare! MRG is entirely benign.

3. Median rhomboid glossitis. Squamous pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia simulating invasive well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (magnification 100x).

7. WELL DIFFERENTIATED ACINIC CELL CARCINOMA WITH LYMPHOID STROMA MIMICKING METASTATIC ACINIC CELL CARCINOMA

Acinic cell carcinoma (AciCC) of the salivary glands is infrequently associated with lymphoid stroma, which, interestingly, is present only in cases of well differentiated AciCC, whereas high-grade lesions usually lack the lymphoid component (26). The important differential diagnosis of AciCC with lymphoid stroma is a lymph node metastasis of an adenocarcinoma originating in the parotid gland (or elsewhere). Identification of a residual nodal architecture with identifiable subcapsular and medullary sinusoids would be indicative of a metastatic lesion but one should also consider the extremely rare cases of true ectopic AciCC primarily arising in intraparotid lymph nodes (27,28). However, we believe that some cases described as primary nodal AciCC (29,30), in fact represent examples of the tumor with lymphoid stroma. Remarkably, in each of these reported cases the growth pattern of the AciCC was microcystic, and lymph node sinusoids were not either documented at all (30) or the provided illustrations were not convincing (29).

4. Well differentiated acinic cell carcinoma with lymphoid stroma mimicking metastatic acinic cell carcinoma within a lymph node (A). Round shaped mass of acinic cell carcinoma with lymphoid stroma. No sinuses can be recognized (B) (magnification 10x and 200x, resp.).

8. JUXTAORAL ORGAN OF CHIEVITZ

The juxtaoral organ of Chievitz is one of the most treacherous pitfalls in surgical pathology with respect to lesions in the head and neck area. It is an enigmatic structure originally described by a Dutch anatomist in 1885 during his study on the development of salivary glands (31). Various names have been given to this structure, including orbital inclusions, buccopharyngeal tract (32), buccotemporal organ (33) and juxtaoral organ (34,35), reflecting diverse theories regarding its embryologic origin (36).

The juxtaoral organ of Chievitz may be quite a frequent finding in humans when meticulous exploration of the area at the angle of the mandible near the insertion of the pterigomandibular raphe is performed (Fig. 8A) (37). Tschen and Fechner found the juxtaoral organ of Chievitz in 14 out of 25 consecutive autopsies in adults who had no evidence of a carcinoma or another lesion of the oral mucosa (35). The squamous cell nests of the juxtaoral organ of Chievitz can manifest luminization (35). The Chievitz organ may cause suspicion of invasion of carcinoma even on radiological examination (38) or it may rarely form a tumoriform mass (39). A case with melanin pigmentation has been described (40). The main surgical pathological significance lies in the fact that the squamous epithelial nests in the juxtaoral organ of Chievitz occur in the vicinity of a peripheral nerve (Fig. 8B); therefore pathologists unwary of the existence of these structures might misinterpret them as a squamous cell carcinoma with a perineurial spread. This mistake is particularly threatening in the patients operated for primary squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and may lead to unnecessary devastating operations. The lack of mitoses and especially the knowledge to the existence of the juxtaoral organ of Chievitz is the best way to avoid such a mistake.

Fig. 8. Juxtaoral organ of Chievitz. (A). Small islands of bland squamous cell epithelium often juxtaposed to twigs of peripheral nerves (B) (magnification 40x and 200x, resp.).

9. METASTASES OF SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA OF THE TONSILS AND OROPHARYNGEAL REGION TO THE NECK SIMULATING CARCINOMA ARISING IN A BRANCHIOGENIC CYST

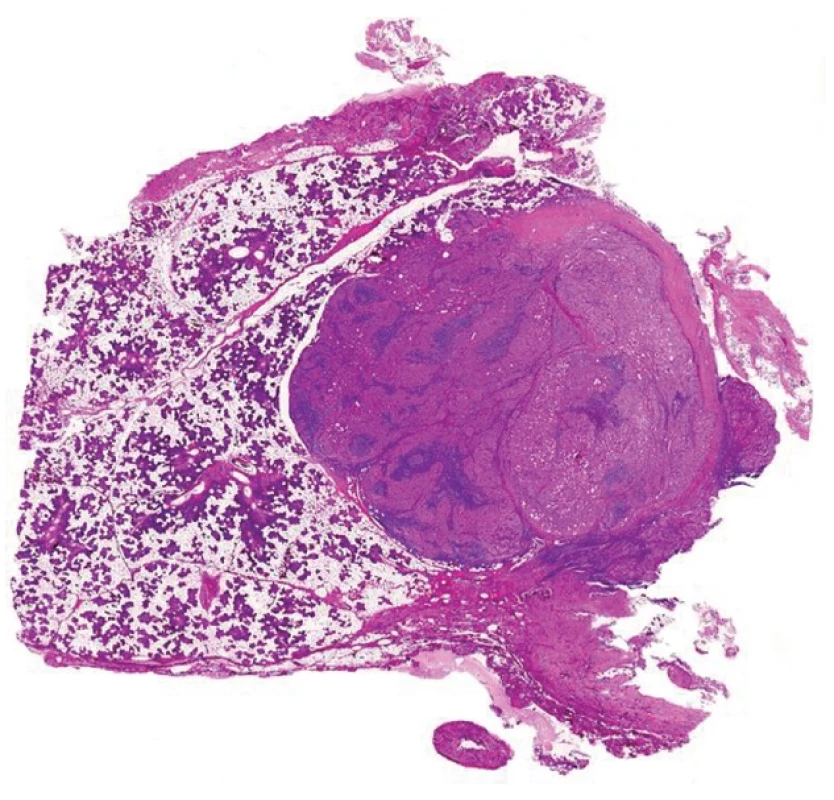

Metastases of squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsils and the oropharyngeal region to the subcutaneous tissues of the lateral neck represents a special pitfall in pathology because these tumors can often metastasize while the primary tumor is occult and silent, sometimes many years after the occurrence of metastatic disease. At scanning magnification, these metastatic lesions can imitate some adnexal tumors, especially a cystic poroid hidradenoma (Fig. 9A,B). Additionally, the epithelium of these tumors often displays the morphology of immature squamous epithelium thus resembling the urothelial transitional cell epithelium (Fig. 9B). These lesions are sometimes misdiagnosed as “squamous cell carcinoma arising in branchiogenic cyst”, probably because of a frequent lymphocytic admixture and epithelial lymphotropism. It should be noted that squamous cell carcinoma hardly, if ever occurs in branchiogenic cysts, and most if not all cases published as such in the older literature likely represent the above phenomenon (41).

At low power magnification, the lesions are cystically changed and multinodular. Very often, there is an accompanying lymphocytic infiltrate, and the cytological features of a high-grade malignant neoplasm may not be apparent at low power view. The primary location of the tumor in most cases is the lingual tonsilar crypt epithelium (42). Many of these tumors are caused by high risk HPV and, accordingly, often demonstrate diffuse and strong immunohistochemical positivity for p16 (43), which appears to be very specific in this context. It is important to diagnose correctly these metastases of HPV caused carcinomas inasmuch as the neoplasms have an excellent prognosis when properly treated (44).

Fig. 9. Metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil. The lesion is cystically changed and surrounded by lymphatic tissue occasioning a resemblance to branchiogenic cyst (A). Cytologically it may look quite blandly and it can simulate an adnexal tumor cystic tumor (B) (magnification 20x and 100x, resp.).

10. ANGIOMATOID CHANGE IN NASAL AND PARANASAL POLYPS

Angiomatoid polyps of the nasal and paranasal region (APNPR) are underrecognized lesions. (Fig. 10A). As recently pointed out by Heffner (45), secondary changes resulting from infarction may impart unusual histopathological appearances causing considerable diagnostic difficulties, and these features have not been adequately described in the literature until recently (46). The most likely explanation of vascular changes in the paranasal inflammatory polyps can be inferred from the anatomical position of the majority of these polyps. They originate mostly in the maxillary sinus. Antrochoanal polyps are polyps that arise in the maxillary antrum and extend into the middle meatus projecting posteriorly through the ipsilateral choana. The polyps that arise in the maxillary sinus and extend into the middle meatus projecting anteriorly are known as antronasal polyps. Less frequently, the origin of sinonasal polyps is in the sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses. They pass through sinus ostia via a small stalk into the nasal cavity, so that the main bulk of the lesion occurs usually in the nasal cavity (47). The growth rate may be prominent and the polyps sometimes extend as far as into the nasopharynx or even oropharynx. Because the polyps may form a large mass with a small stalk and because the stalk extends through a relatively small channel causing a compression and stasis of the feeder vessel, the lesions are particularly subject to secondary changes resulting from chronic or subacute vascular compromise. Rarely, strangulation with necrosis resulting in “autopolypectomy” can be observed. Because a minority of APNPRs occurring in the nasal septum and lateral walls of nasal cavity manifest angiomatoid changes with identical to those seen in lesions involving antrum Highmori, ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses, it is apparent that necrosis may be induced by other means than the strangulation of the stalks of antrochoanal polyps. The most likely explanation appears to be the local pressure caused by the bulky size of the nasal polyp which often entirely obtrudes the whole nasal cavity.

The histology of the secondary changes may range from simple increase in stromal fibrosis to more striking alterations resulting from hemorrhagic infarction, including vascular proliferations simulating angiosarcoma (Fig. 10B,C). Reparative changes, especially those occurring in patients with recurrent disease may result in a large keloid scar, a lesion potentially confused with desmoid fibromatosis (46). The above mechanisms and the extension of the polyp through the paranasal sinus ostium in the lateral nasal cavity wall partly explain bone erosions (48). In our recently published series (46) we have found bone reactive changes in the vicinity of the necrotic polyp masses (Fig. 10D), suggesting that bone necrosis and subsequent reparative skeletal bone process are related to the necrosis of the polyps. In some patients, this bone loss may be impressive. There are on record cases of nasal polyps with severe destruction of the skull bones, and in one case it caused even blindness of the patient (49). This skeletal bone defects may further contribute to the clinical-radiologic impression of an infiltrative growth and possible malignancy.

An important differential diagnostic consideration of APNPR is nasopharyngeal angiofibroma which is a lesion with aggressive growth. Large tumors may have even intracranial extension which often requires extensive surgical approach (50). Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma occurs nearly exclusively in young boys. These clinical features (age and gender) can help in differentiating between nasopharyngeal angiofibroma and APNPR in most cases, as only a minority of APNPRs occurs in this age/gender group. In our consultations, some referring pathologists suggested a diagnosis of nasopharyngeal angiofibroma due to several recurrences of APNPRs, but, overall, a diagnosis of nasopharyngeal angiofibroma was suggested in nearly one third of the referral cases in our recently published series (46). Clinically, APNPR can also be differentiated from nasopharyngeal angiofibroma by the location of the lesion. Appearance of an expansile nasal tumor without a nasopharyngeal mass excludes the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. In addition, anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries are not often involved as the main feeding vessels, and, if they are found, the possibility of a primary nasal mass should be considered instead of a nasopharyngeal mass (51).

The most important differential diagnostic consideration is angiosarcoma. It should be kept in mind that angiosarcomas in this anatomic area are vanishingly rare and most pathologists will probably never encounter one in the paranasal region in their whole professional life. It is likely that most of the few reports of sinonasal angiosarcomas in fact are mistaken diagnoses (48). While we have found in our consultation and routine files 45 cases of APNPR, we have encountered only a single case of paranasal angiosarcoma among nearly 100.000 consultation cases and more than 2.000.000 routine cases (46).

Fig. 10. A: Angiomatoid nasal polyp. B, C: Angiomatoid nasal polyp may display severe atypias and simulate angiosarcoma. D: Bone reactive changes in the vicinity of the necrotic masses of angiomatoid polyp (magnification 100x (A), 200x (BD).

11. EPITHELIAL MISPLACEMENT OF THE VOCAL CORD SQUAMOUS CELL EPITHELIUM

To the best of our knowledge, epithelial misplacement of the vocal cord squamous cell epithelium (EMVCSE) is so far an unpublished phenomenon which represents a diagnostic pitfall. We have seen 15 patients with this lesion that have occurred in adult to old patients, with male predominance. Squamous cell epithelium in these lesions displays various degrees of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, with an interesting feature: the hyperplastic squamous epithelium forms pseudopods of varying lengths, frequently running deep into the stroma of the vocal cords. When these squamous cell pseudopods or bulks of seemingly misplaced epithelium with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia are tangentially cut, they may simulate an invasive squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 11A). The stroma surrounding these pseudopods is usually of two types. Either it is very vascular so that it can impart a pyogenic granuloma-like appearance or it is identical to that seen in singer nodules, revealing stromal edema, vascular ectasia, extracellular amyloid-like fibrin deposits preferentially located around epithelial basal membranes (52). The superficial epithelium can form minute ridges extending from the basal parts of epithelium simulating microinvasion (Fig. 11B).

With respect to differential diagnosis, cases of squamous cell carcinomas of the vocal cords caused by HPV (in our experience 1/3 of all squamous cell carcinomas of this region) are easily distinguished from EMVCSE by negative p16 oncogene immunohistochemical staining, which is a good surrogate for HPV genotyping in these lesions. While HPV induced squamous cell carcinoma of the vocal cords shows strong and diffuse immunoreactivity for p16, EMVCSE reveals only rare, if any p16 positive cells.

Fig. 11. A: Tangentially cut misplaced epithelium mimicking a focus of well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. B: Superficial epithelium showing pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, with epithelial ridges simulating microinvasion (magnification 100x).

Correspondence address:

Prof. MUDr. Michal Michal

Bioptická laboratoř s.r.o.

Mikulášské nám. 4, 32600 Plzeň

e-mail: michal@medima.cz

Sources

1. Chen KTK. Benign signet ring cell aggregates in Peutz-Jeghers polyps: a diagnostic pitfall. Surg Pathol 1989; 2 : 235–238.

2. Michal M, Chlumská A, Mukenšnabl P. Signet ring cell aggregates simulating carcinoma in colon and gallbladder mucosa. Pathol Res Pract 1998; 194 : 197–200.

3. Shiffman R. Signet-ring cells associated with pseudomembranous colitis. Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20 : 599–602.

4. Sidhu JS, Liu D. Signet-ring cells associated with pseudomembranous colitis. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 5 : 542–543.

5. Zámečník M, Gogora M. Signet-ring cells simulating carcinoma in minor salivary glands of the lip. Pathol Res Pract 1999; 195 : 723–724.

6. Ragazzi M, Carbonara C, Rosai J. Nonneoplastic signet-ring cells in the gallbladder and uterine cervix. A potential source of overdiagnosis. Hum Pathol 2009; 40 : 326–231.

7. Dhingra S, Wang H. Nonneoplastic signet-ring cell change in gastrointestinal and biliary tracts: a pitfall for overdiagnosis. Ann Diagn Pathol 2011; 15 : 490–496.

8. Wang HL, Humphrey PA. Exaggerated signet-ring cell change in stromal nodule of prostate: a pseudoneoplastic proliferation. Am J Surg Pathol 2002; 26 : 1066–1070.

9. Oliva E, Young RH. Nephrogenic adenoma of the urinary tract: a review of the microscopic appearance of 80 cases with emphasis on unusual features. Mod Pathol 1995; 8 : 722–730.

10. Guerrero-Medrano J, Delgado R, Albores-Saavedra J. Signet-ring sinus histiocytosis: a reactive disorder that mimics metastatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer 1997; 80 : 277–285.

11. Iezzoni JC, Mills SE. Nonneoplastic emdometrial signet-ring cells. Vacuolated decidual cells and stromal histiocytes mimicking adenocarcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2001; 115 : 249–255.

12. Michal M. Signet-ring cell aggregates simulating carcinoma in colon and gallbladder mucosa. Pathol Res Pract 1998; 194 : 197–200.

13. Lack EE, Delay S, Linnoila RI. Ectopic parathyroid tissue within the vagus nerve. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1988; 112 : 304–306.

14. Lack EE. Hyperplasia of vagal and carotid body paraganglia in patients with chronic hypoxemia. Am J Pathol 1978; 91 : 497–516.

15. Michal M. Ectopic parathyroid within a neck paraganglion. Histopathology 1993; 22 : 85–87.

16. Daum O, Mukensnabl P, Michal M. Mediastinal water clear cell hyperplasia of the parathyroid. Pathol Case Rev 2006; 11 : 218–221.

17. Castleman B, Roth SI. Tumors of the parathyroid glands. In: Atlas of Tumor Pathology; 2nd series, fascicle 14. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1978.

18. Michal M, Plank L, Szepe P, Mukenšnabl P. Lymphoepithelial lesions formed by lymphoma cell infiltration of the solid cell nests of the thyroid gland. Histopathology 1996; 28 : 569–571.

19. Michal M, Mukenšnabl P, Kazakov DV. Branchial-like cysts associated with solid cell nests. Pathol Int 2006; 56 : 150–153.

20. Poli F, Trezzi R, Fellegara G, Rosai J. Multifocal sclerosing thyroiditis. Int J Surg Pathol 2009; 17 : 144.

21. Shimizu M, Hirokawa M, Manabe T. Parasitic nodule of the thyroid in a patient with Graves disease. Virchows Arch 1999; 434 : 241–244.

22. Kolokotronis A, Kioses V, Antoniades D, Mandraveli K, Doutsos I, Papanayotou P. Median rhomboid glossitis. An oral manifestation in patients infected with HIV. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994; 78 : 34–40.

23. Walsh LJ, Cleveland DB, Cumming CG. Quantitative evaluation of Langerhans cells in median rhomboid glossitis. J Oral Pathol Med 1992; 21 : 28–32.

24. Mendez LL, Carrion AB, Freitas MD, Vila PG, Garcia AG, Rey JMG. Rhomboid glossitis in atypical location: case report and differential diagnosis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2005; 10 : 123–127.

25. Delemarre JF, van der Waal I. Clinical and histopathologic aspects of median glossitis. Int J Oral Surg 1973; 2 : 203–208.

26. Michal M, Skálová A, Simpson R.H, Leivo I, Ryška A, Stárek I. Well-differentiated acinic cell carcinoma of salivary glands associated with lymphoid stroma. Hum Pathol 1997; 28 : 595–600.

27. Bhaskar SN. Acinic cell carcinoma of salivary gland-report of 21 cases. Oral Surg 1964; 17 : 62–74.

28. Perzin KH, LiVolsi VA. Acinic cell carcinoma arising in ectopic salivary gland tissue. Cancer 1980; 45 : 967–972.

29. Lidang M, Kier JH. Acinic cell carcinoma with primary presentation in an intraparotid lymph node. Pathol Res Pract 1992; 188 : 226–231.

30. Minic AJ. Acinic cell carcinoma arising in a parotid lymph node. Int J Maxillofac Surg 1993; 22 : 289–291.

31. Chievitz JH. Beiträzur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Speicheldrűsen. Arch Anat Physiol 1885; 9 : 401–436.

32. Brachet A. Sur le tractus bucco-pharingien; organe de Chievitz “Orbital inclusion”. C R Hebd Soc Biol 1919; 71 : 923–925.

33. Zenker W, Hanzl L. Beitrag zur Entwicklung des Chievitzchen Organ beim Menschen. Z Anat Entw Gesch 1953;117 : 215–236.

34. Leibl W, Pflűger H, Kerjaschki D. A case of nodular hyperplasia of the juxtaoral organ in man. Virchovs Arch A Pathol Anat Histol 1976; 371 : 389–391.

35. Tschen JA, Fechner RE. The juxtaoral organ of Chievitz. Am J Surg Pathol 1979; 3 : 147–150.

36. Merida-Velasco JR, Rodriguez-Vazquez JF, de la Cuadra-Blanco C, Salmeron JI, Sanchez-Montesino I, Merida-Velasco JA. Morphogenesis of the juxtaoral organ in humans. J Anat 2005; 206 : 155–163.

37. Lutman GB. Epithelial nests in the intraoral sensory nerve endings simulating perineural invasion in patients with oral carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1974; 61 : 275–284.

38. Kasufuka K, Kameya T. Juxtaoral organ of Chievitz, radiologically suspicious for invasion of lingual squamous cell carcinoma. Pathol Int 2007; 57 : 754–756.

39. Ide F, Mishima K, Saito I. Juxtaoral organ of Chievitz presenting clinically as a tumour. J Clin Pathol 2003; 56 : 789–790.

40. Ide F, Mishima K, Saito I. Melanin pigmentation in organ of Chievitz. Pathol Int 2003; 53 : 262–263.

41. Kazakov DV, Michal M, Kacerovska D, McKee P. Cutaneous Adnexal Tumors. Wolters Kluwer Health, Lippincott, Williams&Wilkins, 2012.

42. Thompson LDR, Heffner DK. The clinical importance of cystic squamous cell carcinomas in the neck. Cancer 1998; 82 : 944–956.

43. McHugh JB. Association of cystic neck metastases and human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Med Lab Pathol 2009; 133 : 1798–1803.

44. Lewis JS, Thorstad WL, Chernock RD, Haughey BH, Yip JH, Zhang Q, El-Mofty SK. P16 positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: an entity with favorable prognosis regardless of HPV status. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34 : 1988–1996.

45. Heffner DK. Problems in pediatric otorhinolaryngic pathology. II. Vascular tumors and lesions of the sinonasal tract and nasopharynx. Int J Pediatr Otolaryngol 1983; 5 : 125–138.

46. Hadravský L, Skalová A, Kacerovská D, Kazakov D.V, Chudáček Z, Michal M. Angiomatoid polyps of nasal and paranasal regions: An underrecognized and commonly misdiagnosed lesion. Report of 45 cases. Virchows Arch 2012, in press.

47. De Vuysere S, Hermans R, Marchal G. Sinochoanal polyp and its variant, the angiomatous polyp. Head Neck Radiol 2001; 11 : 55–58.

48. Heffner DK. Sinonasal angiosarcoma? Not likely (a brief description of infracted nasal polyps). Ann Diagn Pathol 2010; 14 : 233–234.

49. Rejowski JE, Caldarelli DD, Campanella RS, Penn RD. Nasal polyps causing bone destruction and blindness. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1982; 90 : 505–506.

50. Radkovski D, McGill T, Healy GB, Ohlms L, Jones DT. Angiofibroma. Changes in staging and treatment. Arch. Otololaryngol. Head Neck Surg 1997; 123 : 115–116.

51. Som PM, Cohen A, Sacher M, Coi IS, Bryan NR. The angiomatous polyp and the angiofibroma: Two different lesions. Radiology 1982; 144 : 329–334.

52. Cipriani NA, Martin DE, Corey JP, et al. The clinicopathologic spectrum of benign mass lesions of the vocal fold due to vocal abuse. Int J Surg Pathol 2011; 19 : 583–587.

Labels

Anatomical pathology Forensic medical examiner Toxicology

Article was published inCzecho-Slovak Pathology

2012 Issue 4-

All articles in this issue

- Pleomorphic adenoma of salivary glands: diagnostic pitfalls and mimickers of malignancy

- Pseudotumors of the central nervous system

- Histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis / Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (HNL/K-F) and its differential diagnosis: analysis of 19 patients

- Expression of p57 marker in differential diagnosis of complete and partial mole – correlation with DNA analysis

- Pseudotumors and mimickers of malignancy of the head and neck pathology

- Gliosarcoma with alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma-like component: Report of a case with a hitherto undescribed sarcomatous component

- Perineural cell differentiation in ganglioneuromas. Report of 8 cases with immunohistochemical expression of perineural cell markers

- Czecho-Slovak Pathology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Pleomorphic adenoma of salivary glands: diagnostic pitfalls and mimickers of malignancy

- Histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis / Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (HNL/K-F) and its differential diagnosis: analysis of 19 patients

- Pseudotumors of the central nervous system

- Expression of p57 marker in differential diagnosis of complete and partial mole – correlation with DNA analysis

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career