-

Medical journals

- Career

Effects of cervical cerclage on cervical length and the impact of changes in cervical length on pregnancy prognosis

Authors: S. S. R. Herbst 3; A. B. Peixoto 1,2,3; Edward Araujo Júnior 3; A. F. Moron 3; R. Mattar 3

Authors‘ workplace: Mário Palmério University Hospital, University of Uberaba (UNIUBE), Uberaba-MG, Brazil 1; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Federal University of Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM), Uberaba-MG, Brazil 2; Department of Obstetrics, Paulista School of Medicine – Federal University of São Paulo (EPM-UNIFESP), São Paulo-SP, Brazil 3

Published in: Ceska Gynekol 2018; 83(5): 341-347

Category:

Overview

Objective:

To identify any cervix-related morphological and functional marker that can be correlated with pregnancy prognosis in patients who have undergone cerclage for cervical incompetence. Design: An observational and prospective study.

Setting:

Department of Obstetrics, Paulista School of Medicine – Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP-EPM).

Methods:

Patients with cervical incompetence who underwent cervical cerclage using a modified version of the McDonald procedure during or before the 22nd week of pregnancy. The patients were examined by transvaginal ultrasound in the preoperative period, the immediate postoperative period, and between 20 and 24 weeks, 24 weeks + 1 day and 28 weeks, and 28 weeks + 1 day and 32 weeks. Cervical length and the presence of funneling were evaluated during all examinations. Changes in cervical length, presence or absence of funneling, percent increase or decrease in cervical length, and cervical length of less than established values (<25 mm, <20 mm, <15 mm) were determined and correlated with the occurrence of premature birth. Results: Eighty-three patients were evaluated. A significant decrease in cervical length was observed between 28 + 1 day and 32 weeks of pregnancy (from 31.4 ± 8.5 to 29.4 ± 8.9; p = 0.029) compared with cervical length before the cervical cerclage procedure. The longer the cervical length, the longer the pregnancy was found to last. Cervical lengths of <25 mm and <15 mm at 20–24 weeks of pregnancy were found to be highly correlated with delivery <35 weeks.

Conclusion:

Cervical lengths of <25 mm and <15 mm at 20–24 weeks of pregnancy were found to be a risk factor for preterm birth in patients treated with cervical cerclage for cervical incompetence.

Keywords:

cervical incompetence, cervical cerclage, transvaginal ultrasonography, cervical length, preterm birth

INTRODUCTION

Cervical incompetence (CI) is defined as the inability of the cervix to maintain pregnancy during the second trimester in the absence of uterine contractions and labor [1]. It is a frequent condition and is responsible for 16%–20% of pregnancy losses during the second trimester and extreme preterm labor [21].

CI can be diagnosed based on the presence of a classic obstetric history or on a combination of obstetric history and measurements of cervical length during pregnancy through the use of transvaginal ultrasound [10]. Although not used as diagnostic methods, the evaluation of cervical function using Hegar dilators and hysterosalpingography during the intrapartum period enables the identification of possible uterine anomalies and consequent risk factors for CI [10].

In most cases, CI treatment is surgical and may or may not involve the use of progesterone; treatment typically varies only in terms of the procedure employed [3]. Information to identify factors predictive of the success of cervical cerclage remains an important area of study, particularly because extreme preterm birth is an increasingly frequent obstetric complication-one which is responsible for a high rate of neonatal morbidity and mortality [4, 11, 20]. In this regard, transvaginal ultrasound after cervical cerclage is used to evaluate the morphological and biometric parameters of the cervix and thereby to estimate the risk of preterm birth.

Song et al. [19] demonstrated that cervical length measurements after cerclage are predictive of preterm labor. Patients with a cervical length of <25 mm are at a significantly increased risk of labor before 32 weeks of pregnancy. Guzman et al. [9] reported that a cervical length of <10 mm after cerclage had a positive predictive value of 70.6% for preterm birth before 36 weeks. A more recent study found that shortening of the cervix by 1 mm per week after cerclage was associated with a 59% risk of preterm birth [6]. These studies correlated cervical length with a general risk of preterm birth, in which CI is involved as one of several factors.

The objective of this study was to identify cervix-related morphological and functional markers in patients who underwent cervical cerclage using a modified version of the McDonald procedure for CI with two sutures to determine which markers could be correlated with pregnancy prognosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An observational and prospective study was performed by the recurrent miscarriage team of the Department of Obstetrics of the Paulista School of Medicine of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP-EPM) over the course of 24 months. The study was approved by UNIFESP‘s Research Ethics Committee, and the patients who agreed to participate in this study signed an informed consent form.

Pregnant patients underwent cervical cerclage using a modified version of the McDonald procedure with two sutures, which was performed during or before the 22nd week of pregnancy. Cases of multiple births, other cerclage procedures, and loss to follow-up were excluded.

Tests for CI were considered positive when the women underwent both the Hegar 8 test and hysterosalpingography in the intrapartum period and tested positive on at least one of the tests. Pregnant patients undergoing prenatal follow-up without prior confirmation of CI, but with a suspected case based on obstetric history (two or more consecutive pregnancy losses during the second trimester or preterm births at <28 weeks, or both, associated with the minimal presence of symptoms or none at all) were examined by transvaginal ultrasound every 2 weeks starting at the 16th week of pregnancy. Ultrasound screening was considered positive for CI when cervical length was <25 mm, when the cervix was found to have shortened by ≥25% relative to the measurement obtained in the previous evaluation, or when at least 25% funneling was present. Tests for CI were also considered positive in patients with no previous confirmation but who had had three or more pregnancy losses during the second trimester or preterm births before 28 weeks, or both, associated with minimal or no symptoms.

All the cerclage procedures were performed by the same surgeon, who used a modified version of the McDonald procedure with two sutures, as proposed by Pontes et al [14]. In this procedure, two cervical sutures were made: the first was fixed at the top of the internal orifice and the second was fixed below it, i.e., at approximately 1.0 cm from the first suture. The sutures were removed as part of an outpatient procedure around the 38th week of gestation or when necessary as a result of signs of labor. Micronized progesterone was not administered vaginally or orally in any of the cases included in this study.

Transvaginal ultrasounds were performed to measure cervical length and the status of the internal orifice was defined in relation to the presence of funneling. The first evaluation occurred no more than 7 days before the procedure. The second evaluation was performed 15–30 days after the surgical procedure (postoperative period 1 or PO1). The other measurements of cervical length were obtained between 20 and 24 weeks (PO2), 24 weeks + 1 day and 28 weeks (PO3), and 28 weeks + 1 day and 32 weeks (PO4). When funneling was present, proximal cervical length and the cervical length distal to the herniation of the amniotic membrane were measured.

For the examinations, the pregnant patients were asked to completely empty their bladder and then lie in the lithotomy position. Transvaginal ultrasound examinations were performed by three examiners with at least 8 years of experience in ultrasonography using a 7.0-MHz convex transvaginal transducer and an opening angle of 200°. The transducer was inserted into the anterior fornix of the vagina taking care not to put pressure on the cervix to avoid unnecessary stretching. The sagittal image of the cervix was obtained, and the endocervical mucosa (cervical gland area) was used as a guide to the correct position of the internal orifice, thus avoiding confusion with the lower segment of the uterus [17]. Calipers were used to measure the linear distance between the hypoechoic triangular area and the external and internal orifices. In the presence of angular cervical canals, the measurement was performed in two stages in which the cervix was divided into two rectilinear portions. In these cases, the cervical length considered was the sum of the measurements of the two segments [7]. Each ultrasound examination was performed for a period of 5 min to determine any changes to the cervix. Each measurement was repeated three times to ensure the reproducibility of the procedure and, as a consequence, the accuracy of the value found. The lowest value found was considered to be the cervical length of the gestational stage in question.

To characterize the study population, the following variables were evaluated: maternal age, gestational age at the time of cerclage, reason for cerclage indication (obstetric history or current history strongly suggestive of CI, serial ultrasound, obstetric conditions suggestive of CI, and diagnostic tests between births), number of prior pregnancies, number of preterm births and prior miscarriages, whether elective or emergency cerclage was performed, and gestational age at delivery.

The following morphological and functional characteristics of the cervix were also evaluated: cervical length before and after cerclage (PO1, PO2, PO3, and PO4), cervical length of <25 mm, <20 mm, and <15 mm with the occurrence of labor before 35 weeks, percent variation of cervical length in PO1 and PO2 relative to the length before cerclage (cervical enlargement - increase in cervical length >10%, stable – variation ± 10%, decrease – reduction in cervical length <10%), and internal orifice status at the time of cerclage (presence/absence of funneling).

Data were transferred to an Excel 2003 worksheet (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and analyzed using PASW software, version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive analysis was performed using percentages, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate the quantitative variables. Normal distribution variables have been presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables have been expressed as absolute frequency and percentages. To compare the means, Student‘s t-test and Fisher‘s exact test were used as well as the chi-squared test (χ2) for the comparison of categorical variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was used to correlate the cervical length before the cerclage and the time interval between cerclage and birth. The significance level for all tests was p <0.05.

RESULTS

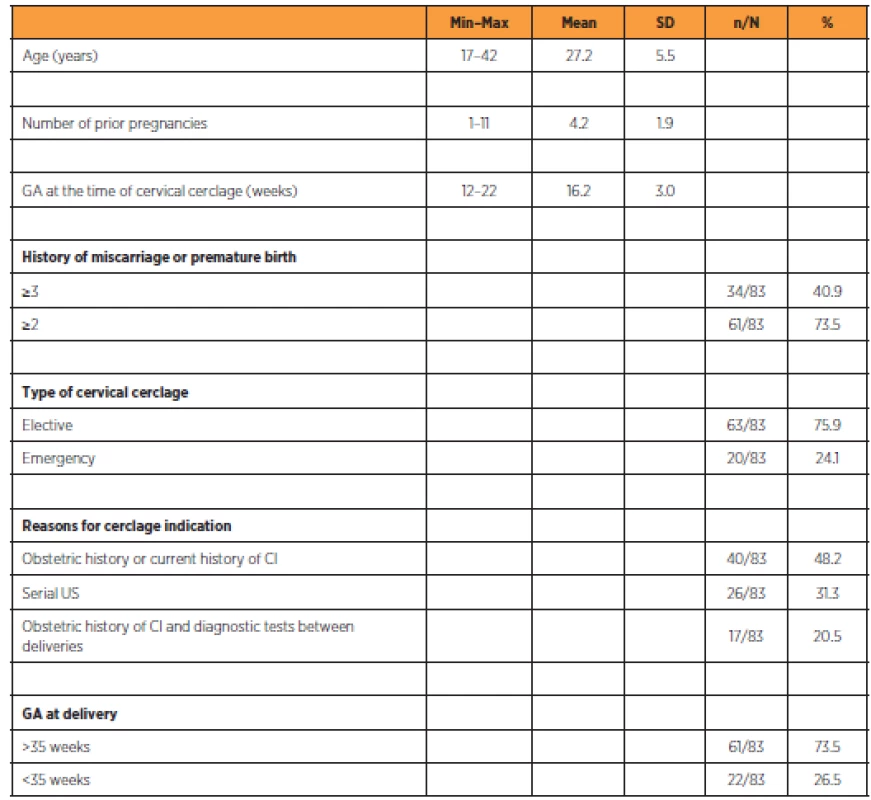

Eighty-three patients were evaluated as part of this study. The mean age ± SD of the patients was 27.2 ± 5.5 years, whereas the number of previous pregnancies was 1-11 (mean 4.2 ± 1.9). Most patients had a history of at least two miscarriages or preterm births in previous pregnancies (73.5%). Elective cerclage was the most commonly performed procedure (75.9%); mean gestational age was 16.2 ± 3.0 weeks. The presence of obstetric conditions or a current history strongly suggestive of CI was the most frequent indication for cerclage in the study population (48.2%). Most births (73.5%) occurred after 35 weeks of gestation (Table 1).

1. Descriptive analysis of the study population

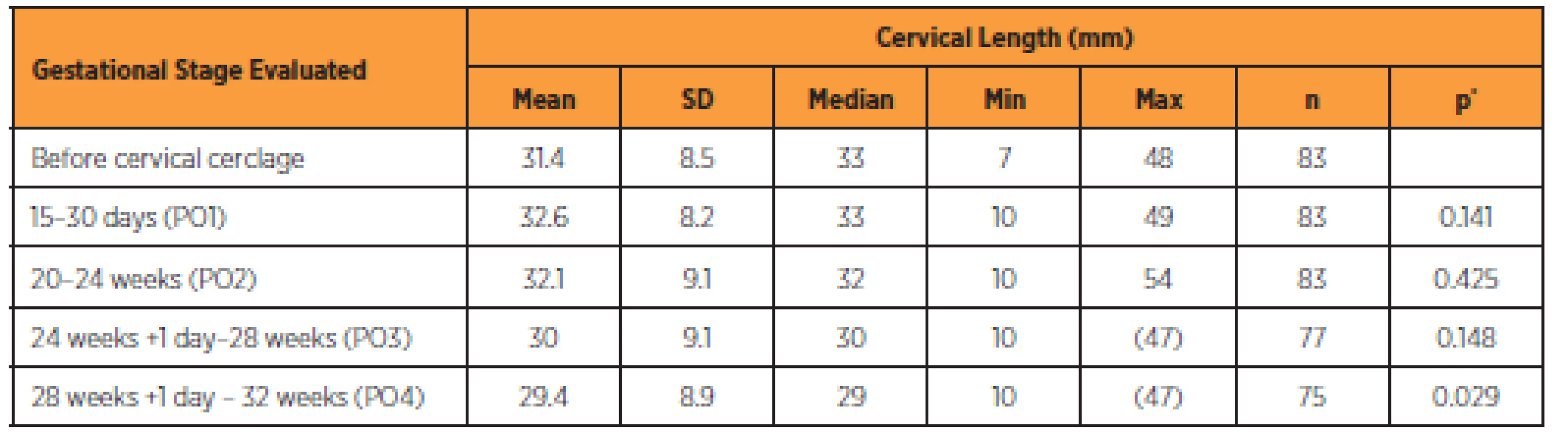

Descriptive analysis of the study population A non-significant increase in cervical length (mm) was observed during PO1 (31.4 ± 8.5 to 32.6 ± 8.2, p = 0.141) and PO2 (31.4 ± 8.5 to 32.1 ± 9.1, p = 0.425). A non-significant decrease in cervical length (mm) was observed during PO3 (31.4 ± 8.5 to 30 ± 9.1, p = 0.148), and a significant decrease in cervical length was observed during PO4 (31.4 ± 8.5 to 29.4 ± 8.9, p = 0.029) compared with the cervical length before the cerclage (Table 2).

2. Comparison between cervical lengths at different stages before and after cervical cerclage

SD: standard deviation, Min: minimum; Max: maximum.

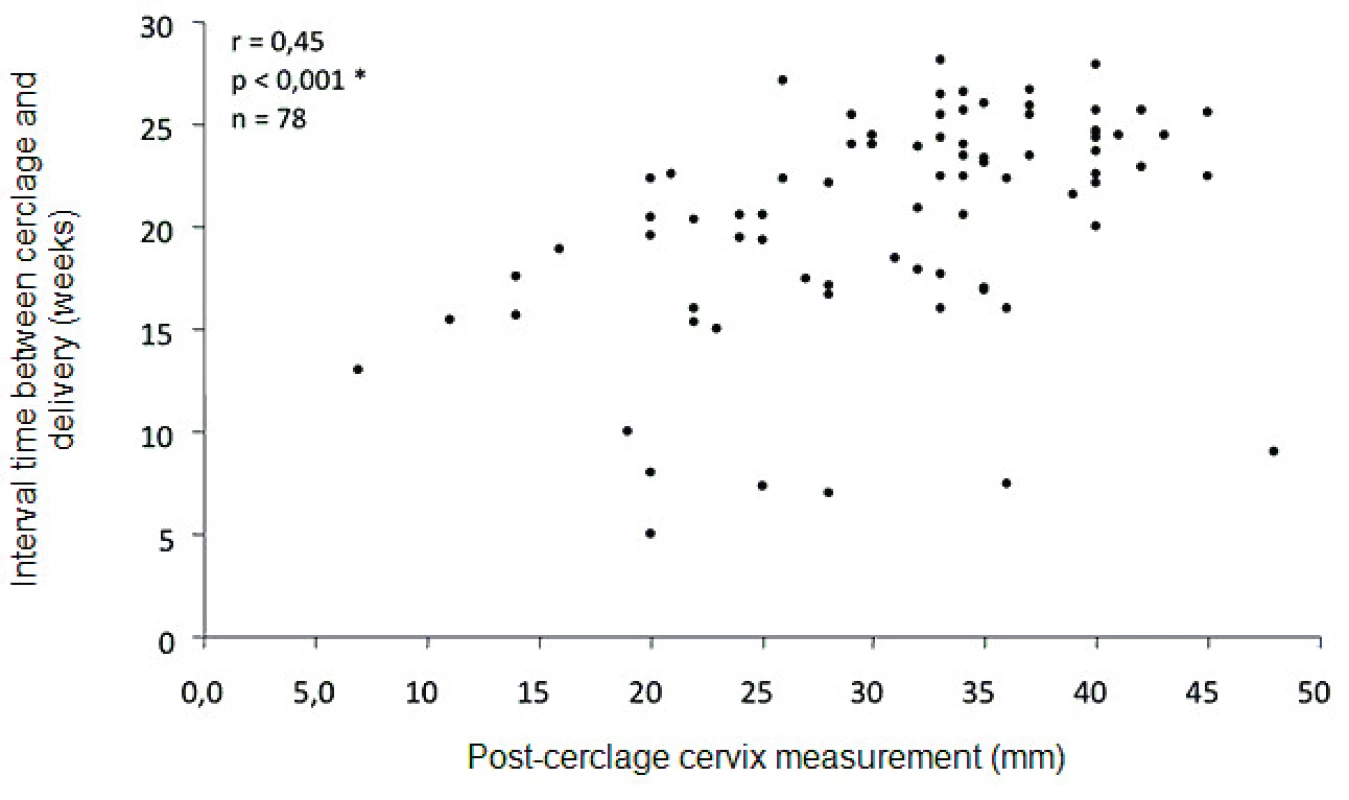

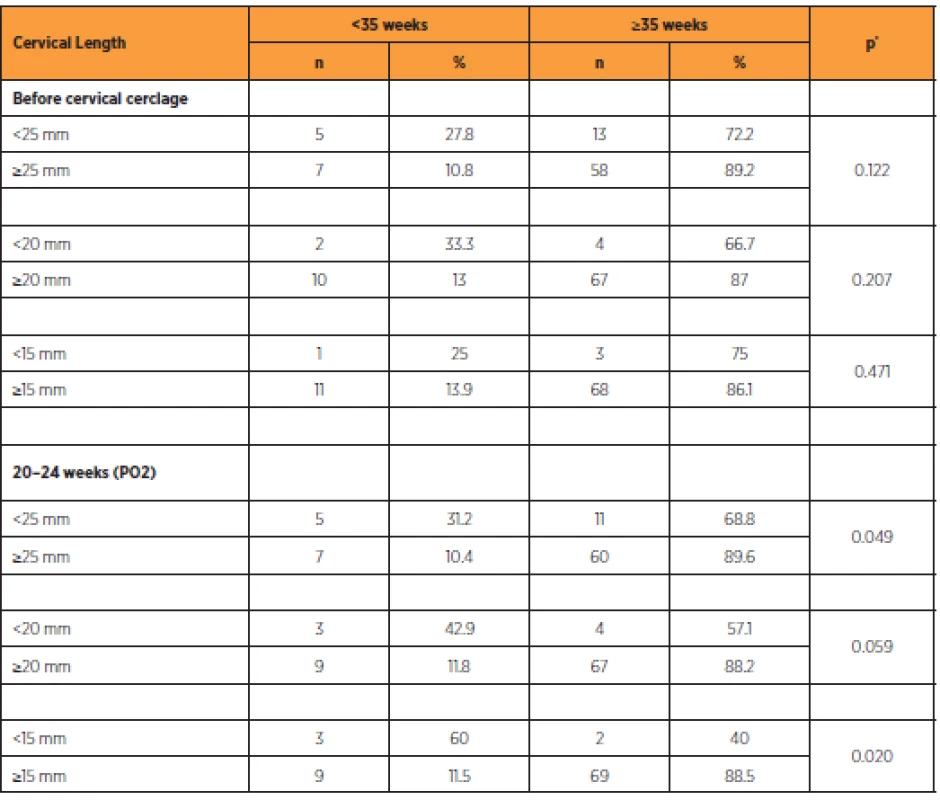

*Student’s t-test.The longer the cervical length before the cerclage procedure, the longer the pregnancy was found to last (Figure 1); however, there was no significant difference between cervical length and gestational age in cases of deliveries < 35 weeks (Table 3). Between 20 and 24 weeks of pregnancy, cervical lengths of <25 mm and <15 mm were also found to be highly associated with delivery <35 weeks (Table 3).

1. Comparison between preoperative cervical length and duration of pregnancy after cervical cerclage

3. Comparison between cervical length and birth before 35 weeks of gestation

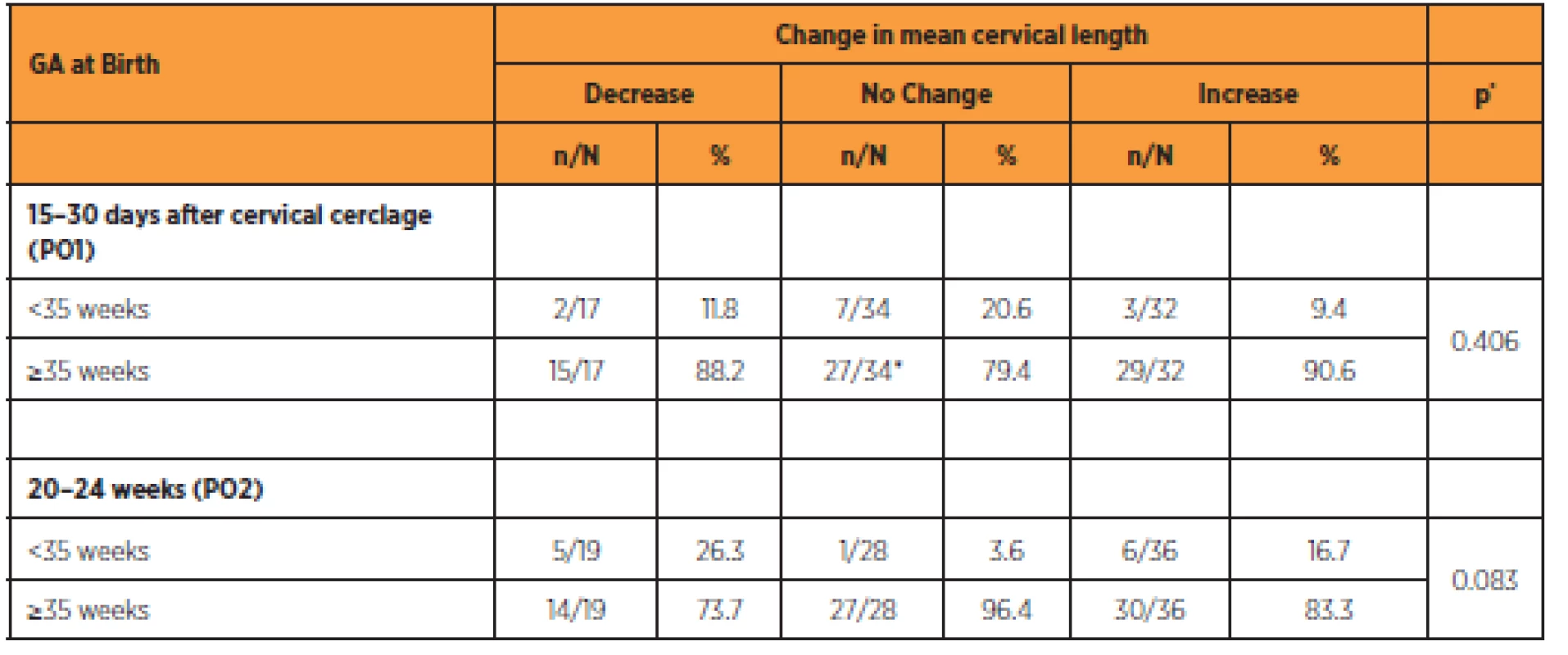

*Fisher’s exact test The variation in cervical length during PO1 and PO2 was not found to be associated with the occurrence of delivery <35 weeks, at 35 weeks, or >35 weeks, respectively (Table 4). No statistically significant association was found between the presence of funneling at the time of cerclage and the occurrence of delivery <35 weeks (p = 0.937).

4. Comparison between changes in cervical length and delivery < 35 weeks of gestation

GA: gestational age, *chi-squared test (χ2) DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the cervical length measurement after cerclage and correlated these values with the risk of preterm birth. We used the McDonald procedure as modified by Pontes, which is a widely used technique in Brazil for cases of CI [15]. In addition, the patients did not receive vaginal progesterone, which may have interfered with the results, since this adjuvant therapy reduces the rates of spontaneous preterm birth [12].

Values in the PO2 period (20–24 weeks) exhibited a tendency to increase relative to the preoperative values, although not statistically significant. However, cervical length of <15 and <25 mm in PO2 were predictors of delivery <35 weeks. In the study by Dijkstra et al. [5] on pregnant women who received elective and emergency cerclage procedures, the mean postpartum cervical length was 34.1 mm; this finding was similar to that of our study, although it was not found to be associated with preterm birth. However, the population used in the study by Dijkstra et al. [15 was markedly heterogeneous; it included women with CI and cases of short cervix (<25 mm) in the second trimester.

The reduction in cervical length in subsequent phases (PO3 and PO4) was not found to be correlated with a risk of preterm birth. In a cohort of low-risk pregnancies in a Brazilian population, the reduction in cervical length seems to be a physiological event in which a slow but significant reduction occurs as gestational age increases (12–36 weeks) [2]. A significant reduction in cervical length (26.6 ± 7 mm before surgery to 13.2 ± 7 mm at delivery) was observed in 20 ICU patients who underwent elective vaginal cerclage at a mean gestational age of 17 weeks [4].

In our study, preoperative measurement of cervical length was not found to be a predictor of preterm birth. According to Groom et al. [8], who evaluated 380 pregnancies at high risk of preterm birth, preoperative cervical length was a better independent predictor than postoperative measurement. In a study by Sim et al. [16] the preoperative measurement of cervical length (whether in elective or emergency cerclage procedures) did not differ in cases of preterm births (<37 weeks) or full-term births (≥37 weeks). We believe that early and elective therapy in most of our cases (75.9%) hastened the onset of the cervical-shortening process with consequent gestational loss or preterm birth, since this process leads to the breakdown of the mechanical protective barrier, thus exposing the amniotic-choriodecidual interface to the external flora [13].

In our sample, we observed no correlation between funneling at the time of cerclage and preterm birth. In a study by Song et al. [18], a short cervix with post-cerclage funneling was found to be a predictor of preterm birth; the mean gestational age at birth was 33.7 weeks when these patients were compared with those with a short cervix and no funneling. However, the study by Song et al. [18] differed from ours in that it evaluated post-cerclage funneling as well.

CONCLUSION

In summary, a cervical length of <25 mm and <15 mm between 20 and 24 weeks of pregnancy was found to be a risk factor for preterm birth in patients treated with cervical cerclage for CI using a modified McDonald procedure.

Correspondence:

Edward Araujo Júnior, PhD

Rua Belchior de Azevedo, 156 apto. 111 Torre Vitoria

CEP 05089-030

São Paulo - SP, Brazil

e-mail: araujojred@terra.com.br

Sources

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No.142: Cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol, 2014, 123(2 Pt 1), p. 372–379.

2. Andrade, KC., Bortoletto, TG., Almeida, CM., et al. Reference ranges for ultrasonographic measurements of the uterine cervix in low-risk pregnant women. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet, 2017, 39(9), p. 443–452.

3. Berghella, V., Rafael, TJ., Szychowski, JM., et al. Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography in women with singleton gestations and previous preterm birth: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol, 2011, 117(3), p. 663–671.

4. Bolla, D., Gasparri, ML., Badir, S., et al. Cervical length after cerclage: comparison between laparoscopic and vaginal approach. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2017, 295(4), p. 885–890.

5. Dijkstra, K., Funai, EF., O‘Neill, L., et al. Change in cervical length after cerclage as a predictor of preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol, 2000, 96(3), p. 346–350.

6. Drassinower, D., Vink, J., Zork, N., et al. Does the rate of cervical shortening after cerclage predict preterm birth? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2016, 29(14), p. 2233–2239.

7. Gramellini, D., Fieni, S., Molina, E., et al. Transvaginal sonographic cervical length changes during normal pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med, 2002, 21(3), p. 227–232.

8. Groom, KM., Shennan, AH., Bennett, PR. Ultrasound-indicated cervical cerclage: outcome depends on preoperative cervical length and presence of visible membranes at time of cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2002, 187(2), p. 445–449.

9. Guzman, ER., Houlihan, C., Vintzileos, A., et al. The significance of transvaginal ultrasonographic evaluation of the cervix in women treated with emergency cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1996, 175(2), p. 471–476.

10. Hua, W., Wei, Z., Ling, F., et al. Effects of Maternal Cervical Incompetence on Morbidity and Mortality of Preterm Neonates with Birth weight Less than 2000g. Iran J Pediatr, 2014, 24(6), p. 759–765.

11. Hui, SY., Chor, CM., Lau, TK., et al. Cerclage pessary for preventing preterm birth in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix at 20 to 24 weeks: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Perinatol, 2013, 30(4), p. 283–288.

12. Jung, EY., Oh, KJ., Hong, JS., et al. Addition of adjuvant progesterone to physical-exam-indicated cervical cerclage to prevent preterm birth. J Obstet Gynaecol Res, 2016, 42(12), p. 1666–1672.

13. Owen, J., Iams, JD., Hauth, JC. Vaginal sonography and cervical incompetence. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2003, 188(2), p. 586–596.

14. Pontes, MD. Abortamento habitual. In: Neme B. Patologia da gestação. São Paulo: Savier; 1988. p. 1–20.

15. Rodrigues, LC., Mattar, R., Camano, L. [Characterization of pregnancy with cervical incompetence]. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet, 2003, 25(1), p. 29–34.

16. Sim, S., Da Silva Costa, F., Araujo Júnior, E., Sheehan, PM. Factors associated with spontaneous preterm birth risk assessed by transvaginal ultrasound following cervical cerclage. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol, 2015, 55(4), p. 344–349.

17. Sonek, J., Shellhaas, C. Cervical sonography: a review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 1998, 11, p. 71–78.

18. Song, JE., Lee, KY., Kim, MY., Jun, HA. Cervical funneling after cerclage in cervical incompetence as a predictor of pregnancy outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2012, 25(2), p. 147–150.

19. Song, RK., Cha, HH., Shin, MY., et al. Post-cerclage ultrasonographic cervical length can predict preterm delivery in elective cervical cerclage patients. Obstet Gynecol Sci, 2016, 59(1), p. 17–23.

20. Taghavi, K., Gasparri, ML., Bolla, D., Surbek, D. Predictors of cerclage failure in patients with singleton pregnancy undergoing prophylactic cervical cerclage. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017 Nov 29. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4600-9. [Epub ahead of print].

21. Weissman, A., Jakobi, P., Zahi, S., Zimmer, EZ. The effect of cervical cerclage on the course of labor. Obstet Gynecol, 1990, 76(2), p. 168–171.Labels

Paediatric gynaecology Gynaecology and obstetrics Reproduction medicine

Article was published inCzech Gynaecology

2018 Issue 5-

All articles in this issue

- HCG level after embryo transfer as a prognostic indicator of pregnancy finished with delivery

- Advance maternal age – risk factor for low birhtweight

- Eating disorders in pregnancy

- Factors affecting the uterine sarcomas developement and possibilities of their clinical diagnosis

- Vaginal microbiome

- The effect of polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorinated pesticides on human reproduction

- Pelvic actinomycosis and IUD

- Screening and the diagnostics of the gestational diabetes mellitus

- Gestational diabetes mellitus

- Effects of cervical cerclage on cervical length and the impact of changes in cervical length on pregnancy prognosis

- Pitfalls in screening for gestational diabetes in the Czech Republic – patient survey

- Consecutive intrapartum uterine rupture following endoscopic resection of deep rectovaginal and bladder endometriosis

- Czech Gynaecology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- HCG level after embryo transfer as a prognostic indicator of pregnancy finished with delivery

- Vaginal microbiome

- Pelvic actinomycosis and IUD

- Eating disorders in pregnancy

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career