-

Medical journals

- Career

Fingolimod attenuates harmaline-induced passive avoidance memory and motor impairments in a rat model of essential tremor

Authors: N. Dahmardeh 1,2; M. Asadi-Shekaari 1,2; S. Arjmand 2; M. Haghani 3; M. Shabani 2

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Anatomical Sciences, Afzalipour Medical Faculty, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran 1; Intracellular Recording Lab, Kerman Neuroscience Research Center, Neuropharmacology Institute, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran 2; Department of Physiology, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran 3

Published in: Cesk Slov Neurol N 2018; 81(6): 691-699

Category: Original Paper

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn2018691Overview

Preclinical data suggest that fingolimod (FTY), a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator, could be beneficial for treating common neurological disorders, including Parkinson‘s disease, MS and epilepsy. In the current study, the effects of FTY on harmaline-induced motor and cognitive impairments were studied in male Wistar rats. Passive avoidance memory, exploratory, anxiety-related behaviours, tremor, and motor function were assessed. The memory impairments observed in harmaline-treated rats were somewhat reversed by administration of FTY. The results showed that FTY could recover step width, left and right step length, but failed to recuperate the mobility duration. FTY improved the time spent in the wire grip and rotarod. Results of our study shed light on the beneficial effects of FTY on cognition and motor function in a model of essential tremor (ET) and suggest that sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulators have a potential neuroprotective profile for the management of ET.

Key words:

essential tremor – fingolimod – memory – motor function

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Chinese summary - 摘要

芬戈莫德在基本震颤的大鼠模型中减弱了骆驼因诱导的被动回避记忆和运动损伤

临床前数据表明,芬戈莫德(FTY)是一种鞘氨醇-1-磷酸受体调节剂,可用于治疗常见的神经系统疾病,包括帕金森病,MS和癫痫。 在目前的研究中,在雄性Wistar大鼠中研究了FTY对骆驼因诱导的运动和认知障碍的影响。 评估被动回避记忆,探索性,焦虑相关行为,震颤和运动功能。 通过施用FTY,在harmaline处理的大鼠中观察到的记忆障碍有所逆转。 结果表明,FTY可以恢复步长,左和右的步长长度,但无法恢复活动时间。 FTY减少了线夹和旋转杆所花费的时间。 我们的研究结果揭示了FTY对特发性震颤(ET)模型中认知和运动功能的有益作用,并提示鞘氨醇-1-磷酸受体调节剂具有治疗ET的潜在神经保护特征。

关键词:

特发性震颤 - 芬戈莫德 - 记忆 - 运动功能

Introduction

Essential tremor (ET) is defined as a slow progress and mono-symptomatic movement disorder [1]. With a high prevalence, estimated to be 20 times higher than Parkinson’s disease, ET is known as the most common type of movement disorders [2]. However, despite its high incidence, the etiology of ET is not yet fully understood. Some clinical studies are indicative that along with tremor, patients also suffer from cognitive deficit [3– 5]. Thus, an association may exist between ET and cognitive impairment or dementia [5]. Particularly, the basis of cognitive impairment in ET is still unclear. Furthermore, no pharmacological therapy for cognitive impairment of ET patients has been developed [5].

Although the pathophysiologic mechanisms of tremor are not clear, many previous experimental studies have provided remarkable insight into the pathogenesis of ET [6]. Several animal models of tremor have been developed for evaluation and finding of therapeutic strategies and pathophysiologic basis of the disease. In this regard, isoproterenol (beta adrenoreceptor agonist), the GABA-A receptor alpha-1 knock-out mouse, and most commonly the harmaline model have been used by several research groups [7,8]. Furthermore, in addition to causing several CNS disorders, there is evidence that harmaline plays a crucial role in cognitive disturbances [5]. Besides, many therapeutic agents that improve human tremor also improve harmaline-induced tremor. Thus, this model is supposed to be a useful animal model for assessment and development of prescribed medications.

Data from several studies suggest that an interaction between the central and peripheral nervous system may lead to tremor [5,9]. However, it is becoming extremely difficult to ignore the existence of a relationship between ET and the abnormality in the Guillain-Mollaret triangle (rubral nucleus, inferior olive nucleus [ION] and cerebellum) [10]. Exposure to harmaline has been shown to induce ET via activation of the olive-cerebellar system [8]. It is therefore likely that such connections may exist between ION dysfunction and ET [11]. Moreover, it has previously been observed that harmaline increases the ION neuron excitability [12]. Thus, decrement of neuronal excitability of ION by any treatment modality can be a therapeutic target in the treatment of ET.

Fingolimod (FTY) is a fungus metabolite derived from myriocin and known as sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor agonist [13]. In recent years, we and other researchers have investigated a variety of approaches for FTY and have revealed beneficial effects on treatment of tremor, MS, acute kidney injury, Alzheimer’s disease, and stroke [14– 16]. Evidence suggests that FTY easily crosses the blood brain barrier and modulation of its receptors expressed on the neural cells may exert neuroprotective functions within the CNS [17].

Furthermore, it has been shown that FTY regulates the plasticity and cell survival in the brain through increase in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor and may be useful in the treatment of cognitive deficits related to neuronal disorders [18]. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to analyze the possible neuroprotective effects of FTY on motor and cognitive deficits induced by harmaline in the experimental model of ET.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (40– 60- g, one month old) were used in this study. The rats were divided into five groups of saline, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), harmaline, harmaline + DMSO and FTY + harmaline (N = 10 for each group). All the procedures in this experiment were carried out according to the Neuroscience Research Center of Kerman Medical University (Ethics Code: KNRC/ REC/ 96/ 1456). All of the animals were maintained on a 12-h light-dark cycle with food and water ad libitum.

Design of the study

Harmaline hydrochloride dihydrate and FTY were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Munich, Germany) and dissolved in normal saline and DMSO, resp. The FTY was administered (1 mg/ kg, intraperitoneally [i. p.]) 24 h before harmaline injection (30 mg/ kg, i. p.). Saline was considered as control (vehicle) for harmaline and DMSO for FTY. Thirty min after administration of harmaline, behavioural tests, including open field, wire grip (three trials 180-s with 5-min inter-trial interval), rotarod (three trials 300-s cut off and inter-trial intervals of 5 min) and foot print were carried out with adequate amount of rest between each trial and lasted for 3 h in total. Three hours after the end of these behavioural tests, shuttle box test was performed.

Behavioural studies

Observation

An observer who was blinded to the groups under the study rated the tremors. Thirty min after administration of harmaline, during the open field test, tremor data were quantitatively scored using a four-point scale and grading neurological deficit score test. The normal motor function or no observable tremor was represented by score of 0, occasional tremor affecting only the head and neck was considered as a score of 1, intermittent (occasional tremor affecting all body parts) was represented by score of 2, persistent (persistent tremor affecting all body parts and tail) was scored 3, and severe (persistent tremor rendering the animal unable to stand and/ or walk) was considered as a score of 4 [19].

Open-field test

The apparatus of open field consisted of an arena made of opaque Plexiglas (90 ×90 × 45 [H] cm). The arena floor was divided into 16 small squares to define the central and peripheral sections. The rats were placed in the centre of the arena and their behaviour was recorded during a 5-min interval by an automated video tracking system (Ethovision [Noldus Technology, Wageningen, the Netherlands]). The total time spent in the centre or periphery and the total distance moved were recorded. Between the sessions, the chamber was cleaned with 70% ethanol [5].

Rotarod test

An accelerating rotarod was used to evaluate the motor coordination and balance performance. Prior to experiment, all animals were trained for the test. The experiment started with a speed of 10 rpm and the rod linearly accelerated to 60 rpm. Each rat undertook three trials with inter-trial interval of 30 min. The maximum cut off time of each trial was 300 s. The total duration of each rat remaining on the rod (fall latency) was measured for evaluation of balance performance [20,21].

Wire grip test

We used the wire grip test to check the muscle strength and balance. Each rat suspended with the forepaws on a horizontal steel wire (80 cm long, diameter 6 mm) and held in vertical position while it grasped the wire. Each rat was given three trials with a 30-min inter-trial rest interval. For each animal, the latency to fall was recorded with a stopwatch [22].

Gait analysis test (Footprint)

This test assesses the animal’s walking patterns and gait kinematics. To perform this experiment, the hind paws of each rat were stained with non-toxic inks and the animals were allowed to transverse freely through a plexiglass tunnel (100 [length] × 10 [width] × 10 [height] cm) ending in a darkened cage. The floor of the tunnel was lined with a fresh sheet of white absorbent paper at each final test. The hind paw stride lengths were measured by the distance (cm) between the respective paw prints to the centre of the ipsilateral print. The hind paw stride widths were measured through the distance between the centres of the respective paw prints to the corresponding contralateral stride length measurements at a right angle. Footprints at the beginning and at the end of each run were not measured [23].

Passive avoidance test

This test, as a fear-aggravated test, is used for evaluating learning and memory in rodents. The shuttle box device with dimensions of 100 [length] × 25 [width] × 25 [height] cm and consisting of two compartments (light and dark) separated by a door was used. In this experiment, the animal learns to avoid an environment in which a prior aversive stimulus has been delivered. In the learning phase of the test, the animals were familiarized with the test by putting them in the light chamber (door closed) for 5 min. The next day, each rat was returned to the light compartment, the door opened and the animal was allowed to move to the dark chamber before the door was closed. This phase was repeated once and if an animal failed to move into the dark compartment, it was removed from the study. One hour later, each animal was placed in the light compartment, the door opened, and on entering the dark compartment, was given an electric shock (0.5 mA, 2 s; via wires embedded in the dark chamber floor) [24,25]. This part of the process was repeated up to 5× at 1-h intervals until the animal learned to avoid the dark compartment (remaining in light compartment for at least 300 s) and the number of shocks required for learning was recorded. Twenty-four hours after the learning phase, the assessment phase of the test was undertaken. The animal was placed in the light chamber (door opened) and the time until the animal entered the dark compartment recorded as the step-through latency (STL). The total time spent in the dark compartment (TDC) during a period of 5 min was also recorded [5].

Statistical analysis

Graph Pad Prism 6 (Graph Pad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis of data and figure production. All data were first assessed for normality using a Kolmogorov--Smirnov test. The normally distributed data were then analyzed using one-way ANOVA test. Where a main effect was seen in ANOVA tests, pairwise comparisons between groups were then made using Tukey’s post hoc analysis. Data that were not normally distributed were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis test. All data were expressed as median and interquartile range and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The effect of FTY on tremor and gait disorder

The results obtained from the tremor scale score showed an increase in tremor in the harmaline group compared to the saline group (p < 0.05). Although the score of FTY group showed a significant increment compared to the saline group, it is apparent that FTY has improved the tremor scale score compared to the harmaline group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1A). Moreover, the hind paw stride width, an indication for gait, was also higher in the harmaline group, as compared to the saline group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1B). In addition, the FTY recovered the gait in this group compared to saline group (p < 0.05). However, FTY did not completely improve and recover the gait back to the control levels (Fig. 1B). The saline and DMSO groups showed the same levels for tremor scale score and gait.

1. Effect of FTY on tremor scores (A), step width (B), left (C) and right step length (D) after harmaline (30 mg/kg, intraperitoneally [i. p.]) administration. The tremor score increased in the rats in harmaline group compared to the control groups. Hind step width also significantly increased. Tremor score and hind step width were signifi cantly decreased by FTY treatment compared to the saline + harmaline and DMSO + harmaline groups. Values are represented as medians with interquartile ranges as a box and max./min. as whiskers. No data points were excluded as outliers in the presented analyses.

DMSO – dimethyl sulfoxide; FTY – fingolimod

* p < 0.05, significantly different from the control group

# p < 0.05, significantly different from the vehicle (DMSO, i.p.) treated group

× p < 0.05, significantly different from the harmaline treated group

¤ p < 0.05, significantly different from the harmaline + DMSO treated group

Obr. 1 Účinek FTY na skóre tremoru (A), šířku kroku (B), délku levého (C) a pravého kroku (D) po podání harmalinu (30 mg/kg, intraperitoneálně [i. p.]). Skóre tremoru se zvýšilo u potkanů ve skupině s harmalinem v porovnání s kontrolními skupinami. Rovněž se významně zvýšila šířka zadního kroku. Podání FTY významně snížilo skóre tremoru a šířku zadního kroku v porovnání se skupinami s podáním fyziologického roztoku + harmalinu a DMSO + harmalinu. Hodnoty jsou uvedeny jako mediány v krabicovém grafu s krabicí znázorňující mezikvartilové rozpětí a max./min. hodnotami jako anténami. V předkládaných analýzách nebyly žádné datové body vyloučeny jako odlehlé hodnoty.

DMSO – dimethylsulfoxid; FTY – fingolimod

* p < 0,05, významně se lišící od kontrolní skupiny

# p < 0,05, významně se lišící od skupiny s podáním vehikula (DMSO, i.p.)

× p < 0,05, významně se lišící od skupiny s podáním harmalinu

¤ p < 0,05, významně se lišící od skupiny s podáním harmalinu + DMSO![Effect of FTY on tremor scores (A), step width (B), left (C) and right step length (D) after harmaline (30 mg/kg, intraperitoneally

[i. p.]) administration. The tremor score increased in the rats in harmaline group compared to the control groups. Hind step width also significantly increased. Tremor score and hind step width were signifi cantly decreased by FTY treatment compared to the saline + harmaline and

DMSO + harmaline groups. Values are represented as medians with interquartile ranges as a box and max./min. as whiskers. No data points

were excluded as outliers in the presented analyses.<br>

DMSO – dimethyl sulfoxide; FTY – fingolimod<br>

* p < 0.05, significantly different from the control group<br>

# p < 0.05, significantly different from the vehicle (DMSO, i.p.) treated group<br>

× p < 0.05, significantly different from the harmaline treated group<br>

¤ p < 0.05, significantly different from the harmaline + DMSO treated group<br>

Obr. 1 Účinek FTY na skóre tremoru (A), šířku kroku (B), délku levého (C) a pravého kroku (D) po podání harmalinu (30 mg/kg,

intraperitoneálně [i. p.]). Skóre tremoru se zvýšilo u potkanů ve skupině s harmalinem v porovnání s kontrolními skupinami. Rovněž se významně

zvýšila šířka zadního kroku. Podání FTY významně snížilo skóre tremoru a šířku zadního kroku v porovnání se skupinami s podáním

fyziologického roztoku + harmalinu a DMSO + harmalinu. Hodnoty jsou uvedeny jako mediány v krabicovém grafu s krabicí znázorňující mezikvartilové

rozpětí a max./min. hodnotami jako anténami. V předkládaných analýzách nebyly žádné datové body vyloučeny jako odlehlé

hodnoty.<br>

DMSO – dimethylsulfoxid; FTY – fingolimod<br>

* p < 0,05, významně se lišící od kontrolní skupiny<br>

# p < 0,05, významně se lišící od skupiny s podáním vehikula (DMSO, i.p.)<br>

× p < 0,05, významně se lišící od skupiny s podáním harmalinu<br>

¤ p < 0,05, významně se lišící od skupiny s podáním harmalinu + DMSO](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image_pdf/f447644e5bcdf591389ed16e238d48ab.png)

These data showed that treatment with harmaline induced severe tremor associated with significant functional deficits. Furthermore, a main effect for treatment with harmaline and/ or FTY upon left (Fig. 1C) and right (Fig. 1D) step lengths was not detected.

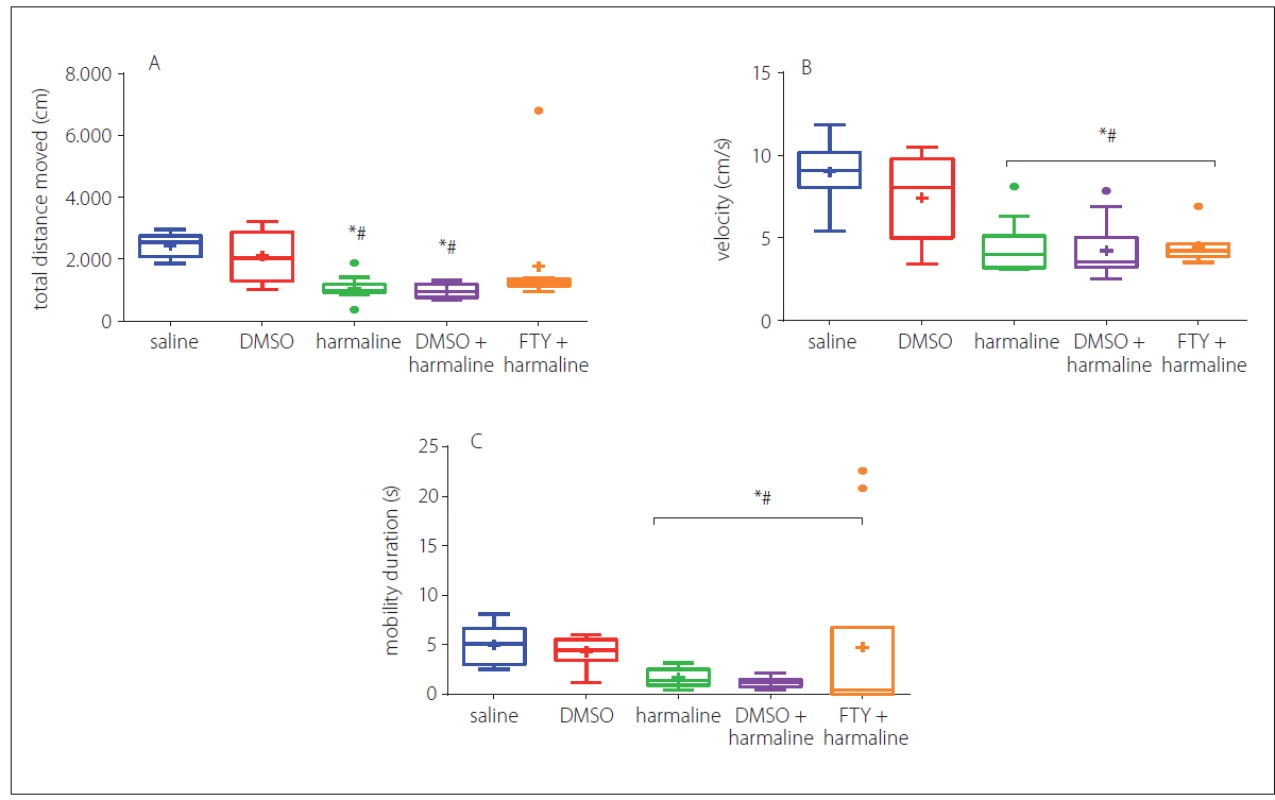

The effect of FTY on explorative and anxiety-like behaviours

Harmaline and harmaline + DMSO groups showed a significant decrease in total distance moved as compared to the control group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). No significant difference was observed among FTY, saline and DMSO groups (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2A). In Fig. 2A, B, there was a clear and significant trend of decrease in velocity (Fig. 2B) and mobility (Fig. 2C) upon treatment with harmaline and/ or FTY. The results indicated that the rats in FTY+ harmaline and harmaline plus DMSO groups showed a decrease in velocity (Fig. 2B), mobility (Fig. 2C) compared to the saline and DMSO groups (p < 0.05) indicating that FTY treatment did not have any effects on harmaline-induced disturbances in velocity and mobility (p > 0.05, Fig. 2B, C). No significant difference in duration of staying in the centre and peripheral zones was observed which is an indirect indicator of anxiolytic-like effects and implies that there is no impaired anxiety-like behaviour at least in the open field test (data have not shown).

2. The effect of FTY on exploratory and anxiety-like behaviour disturbance induced by harmaline. Total distance moved (A), velocity (B) and mobility duration decreased in the harmaline and DMSO + harmaline treated groups as compared to the control group but there was no signifi cant difference between the FTY and control groups in total distance moved. Values are represented as medians with interquartile ranges as a box and max./min. as whiskers.

DMSO – dimethyl sulfoxide; FTY – fi ngolimod

*p < 0.05 as compared to the control group

#p < 0.05 as compared to the DMSO group

×p < 0.05 as compared to the harmaline group

¤p < 0.05 as compared to the harmaline + DMSO group

Obr. 2 Účinek FTY na poruchu průzkumného chování a chování souvisejícího s úzkostí navozenou harmalinem. Celková uražená vzdálenost (A), rychlost (B) a doba trvání mobility se ve skupině s podáním harmalinu a ve skupině s podáním DMSO + harmalinu snížily v porovnání s kontrolní skupinou, nebyl však pozorován žádný významný rozdíl v uražené vzdálenosti mezi FTY a kontrolní skupinou. Hodnoty jsou uvedeny jako mediány v krabicovém grafu s krabicí znázorňující mezikvartilové rozpětí a max./min. hodnotami jako anténami.

DMSO – dimethylsulfoxid; FTY – fingolimod

*p < 0,05 v porovnání s kontrolní skupinou

#p < 0,05 v porovnání se skupinou s podáním DMSO

×p < 0,05 v porovnání se skupinou s podáním harmalinu

¤p < 0,05 v porovnání se skupinou s podáním harmalinu + DMSO

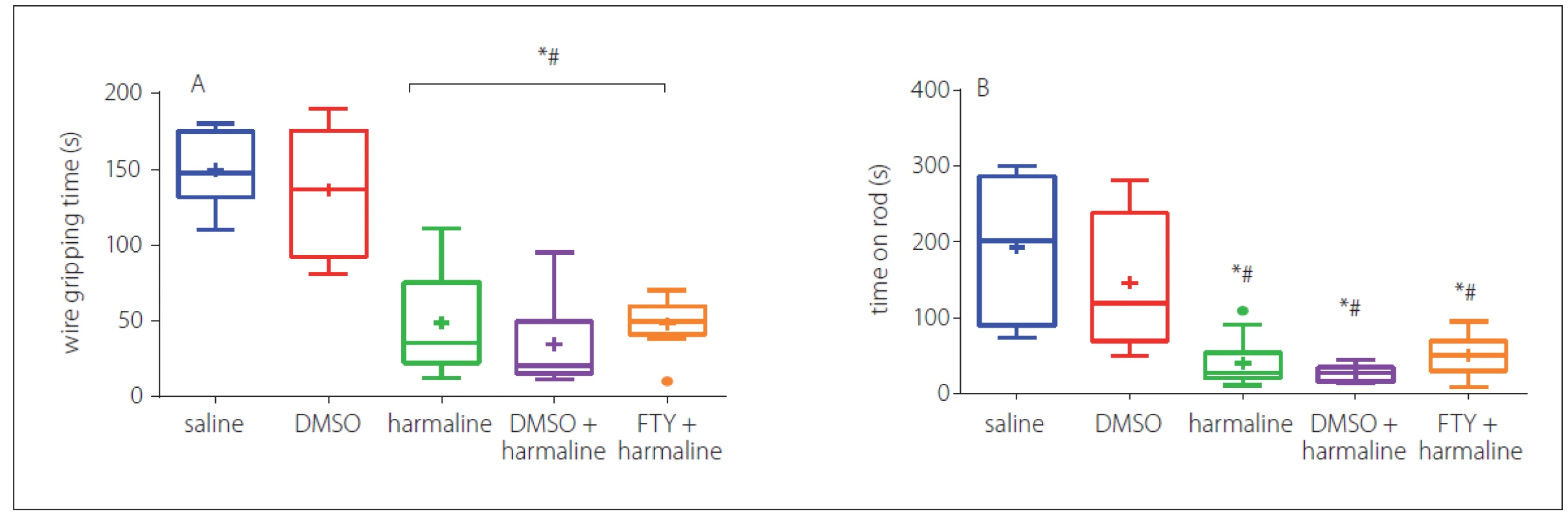

The effect of FTY on muscle strength and balance function

In order to assess the muscle strength and balance function, we performed a wire grip test. In three consecutive trials, the animals of the harmaline and harmaline + DMSO groups showed a decrease in falling time and the time taken on the rod as compared to the control group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3A). However, FTY treatment did not show any recovery impact for either parameters. Rats of the FTY and harmaline groups spent a shorter duration on the wire grip as compared to the saline and DMSO groups (p < 0.05). Moreover, no significant differences were observed among FTY, harmaline, and harmaline + DMSO groups (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3A).

3. Effect of FTY on muscle strength and balance function after harmaline administration: A – mean latency to fall in wire grip test; B – falling time in three trials in rotarod test. The rats in the FTY and harmaline groups spent a shorter duration on the wire grip as compared to the control groups. The rats in the harmaline and harmaline + DMSO groups showed a significant decrease in falling time compared to the control group and the time taken on the rod as compared to the control group. No significant differences were observed among FTY, harmaline, and harmaline + DMSO groups.

DMSO – dimethyl sulfoxide; FTY – fingolimod

*p < 0.05 as compared to the control group

#p < 0.05 as compared to the DMSO group

×p < 0.05 as compared to the harmaline group

¤p < 0.05 as compared to the harmaline + DMSO group

Obr. 3 Účinek FTY na svalovou sílu a rovnováhu po podání harmalinu: A – průměrná latence do pádu v testu závěsu na lanku; B – doba do spadnutí ve třech pokusech v testu na rotující tyči. Potkani ve skupinách s podáním FTY a harmalinu strávili kratší dobu v závěsu na lanku v porovnání s kontrolními skupinami. Potkani ve skupině s podáním harmalinu a ve skupině s harmalinem + DMSO vykazovali významné snížení doby do spadnutí v porovnání s kontrolní skupinou a doby strávené na tyči v porovnání s kontrolní skupinou. Nebyly pozorovány žádné významné rozdíly mezi skupinami s podáním FTY, harmalinu a harmalinu + DMSO.

DMSO – dimethylsulfoxid; FTY – fingolimod

*p < 0,05 v porovnání s kontrolní skupinou

#p < 0,05 v porovnání se skupinou s podáním DMSO

×p < 0,05 v porovnání se skupinou s podáním harmalinu

¤p < 0,05 v porovnání se skupinou s podáním harmalinu + DMSO

In addition, the balance function was evaluated by averaging the three repeated trials of the time stayed on rod; the result indicated that harmaline significantly (p < 0.05) decreased the time on the rod when compared with the saline group, but FTY failed to increase the time that animals spent on the rod. No significant difference was observed between the FTY and harmaline and harmaline + DMSO groups (Fig. 3B).

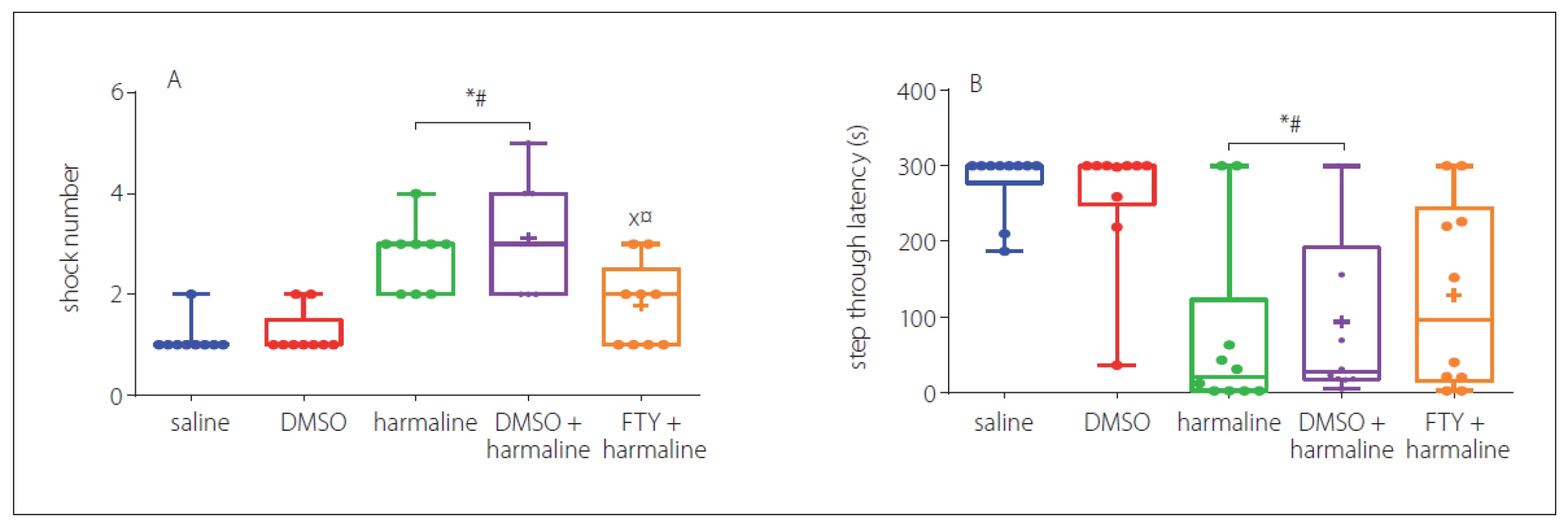

The effect of harmaline and FTY on passive avoidance

In this test, the number of shocks that animals received for the learning phase evaluated the effects of treatment with FTY. In Fig. 4A, it can be seen that the harmaline and harmaline + DMSO groups required significantly more shocks to learn the task (p < 0.05 vs. saline). However, further analysis showed that FTY treatment improved the learning impairment induced by harmaline (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). In addition, 24 h after learning, the effect of treatment on the step through latency, an index for memory retrieval, was evaluated. The result revealed that this measure was significantly decreased in both harmaline and harmaline + DMSO groups (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4B) compared with the saline groups. Treatment with FTY not only improved learning, but also partially improved the STL time to the level of saline group. However, no significant difference was observed between the harmaline + FTY and harmaline and harmaline + DMSO groups. This result indicates that FTY treatment was able to partially improve the harmaline-induced reduction in the step through latency. Moreover, we evaluated the total time spent in the dark compartment. The rats in the harmaline group spent more time in the dark chamber compared with the saline group, while pretreatment with FTY non-significantly decreased this parameter compared with the harmaline group.

4. Effect of FTY on passive avoidance after harmaline administration: A – number of shocks; B – step through latency. The harmaline and harmaline + DMSO groups required significantly more shocks to learn the task compared to the control groups. FTY treatment improved the learning impairment induced by harmaline comparing control groups. Legends merged on each bar indicate group sizes.

DMSO – dimethyl sulfoxide; FTY – fingolimod

*p < 0.05 as compared to the control group

#p < 0.05 as compared to the DMSO group

×p < 0.05 as compared to the harmaline group

¤p < 0.05 as compared to the harmaline + DMSO group

Obr. 4 Účinek FTY na pasivní vyhýbání po podání harmalinu: A – počet šoků; B – latence vstupu do tmavého oddílu. Skupiny s podáním harmalinu a harmalinu + DMSO potřebovaly významně vyšší počet šoků, aby se naučily danou úlohu, v porovnání s kontrolními skupinami. Podání FTY zlepšilo poruchu učení navozenou harmalinem v porovnání s kontrolními skupinami. Body zobrazené na každém sloupci ukazují velikosti skupin.

DMSO – dimethylsulfoxid; FTY – fingolimod

*p < 0,05 v porovnání s kontrolní skupinou

#p < 0,05 v porovnání se skupinou s podáním DMSO

×p < 0,05 v porovnání se skupinou s podáním harmalinu

¤p < 0,05 v porovnání se skupinou s podáním harmalinu + DMSO

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that pretreatment with FTY improved learning, memory deficit, and tremor status in the rat’s model of tremor induced by harmaline, as evaluated by several behavioural tasks. However, there were no significant improvements in muscle strength, balance function, explorative, and anxiety-like behaviour.

Harmaline induces action dependent tremor, and is well-noted as an easy animal model for seeking and evaluating new therapies for ET [26– 28]. After injection of harmaline, tremor developed immediately. Consistent with this notion, we showed that harmaline induced tremor, which was seen as marked deficits in the performance of all behavioural tasks employed. One possible explanation for harmaline induced tremor might be that it synchronizes the electrical activity in the ION [29]. Moreover, evidence shows that the harmaline causes an increase in excitability by opening calcium channels and subsequently bringing about tremor [30]. Many studies have shown that the use of T-type calcium channel blockers in treating neurological diseases in animal models is promising [31]. Recent studies have demonstrated that pulses of T-type calcium in the ION increased by harmaline and T-type calcium channel blockers might be of therapeutic potential for the treatment of tremor [32].

In the current study, we examined the effect of FTY pretreatment upon harmaline-induced tremor and its symptoms. FTY alleviated some symptoms associated with ET in a potentially relevant animal model. The findings of our previous study provided the pharmacological evidence for the specific involvement of S1P receptors in mediating motor deficits induced by harmaline and demonstrated that pretreatment with FTY one hour before harmaline injection could exert protective impacts on impaired locomotion and balance in harmaline--exposed animals [33]. In line with these findings, in the current experiment, FTY significantly decreased the harmaline--induced tremor score, showing helpful effects on the behavioural disturbance exhibited. There are no precise putative mechanisms to explain how FTY exhibits such ameliorative effects, but it may partly be explained by the fact that FTY directly inhibits the atrioventricular conduction [34]. It is also possible that FTY inhibits firing activity at ION and modulates tremor and further research should be ensued to investigate the direct effects of FTY on firing properties of the neurons of the ION.

In addition, we and other researchers have shown that harmaline impaired the muscle strength and balance function [26,35]. Although FTY showed a beneficial effect on tremor, it failed to improve the muscle strength and balance function in the harmaline treated rats. A finding that could be explained by the fact that impairment of muscle strength and balance function may be related to peripheral deficit in muscles rather than the CNS activity. This claim can also be supported by the results of explorative and anxiety-like behaviours where FTY failed to recover these responses. In addition, since harmaline acts as weak or partial agonist of benzodiazepine receptors [36], it has been suggested that its actions may in part be mediated by the benzodiazepine receptors which have a crucial role in the regulation of anxiety [37]. However, our results delineate that FTY might not interact with benzodiazepine receptors to lessen anxious-related behaviours.

In the passive avoidance test, it was shown that harmaline impaired the learning and memory performance as indicated by increased number of received shocks and STL time. It has been suggested that harmaline inactivates gastrointestinal monoamine oxidase and allows the first-pass metabolism of dimethyltryptamine access to systemic circulation and the CNS system where dimethyltryptamine acts as an injurious insult [38]. However, FTY improved the STL and memory performance in harmaline treated animals. It has been suggested that administration of FTY improves learning and memory in the rat’s model of Alzheimer’s disease [39]. The FTY may also act directly via S1P receptors and thereafter activates endogenous neuroprotective mechanisms [40]. Furthermore, it has been shown that FTY ameliorates neural deficit and synaptic plasticity impairment in stroke, independent from its immunosuppressive effects [16]. Moreover, recent evidence has demonstrated that FTY increases the production of neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor and mediates neuroprotective functions [41]. In conclusion, FTY appears to act as a neuroprotective factor to improve learning and memory impairment induced by harmaline and more investigations are needed to evaluate the mechanism of therapeutic effects of FTY on motor and cognitive impairments.

Funding for this study was provided by Kerman University of Medical Sciences as a grant for the PhD research of Narjes Dahmardeh.

Accepted for review: 10. 5. 2018

Accepted for print: 31. 10. 2018

Mohammad Shabani, PhD

Kerman Neuroscience Research Center

Neuropharmacology Institute

Kerman University of Medical Sciences

Jehad Blvd

Ebn Sina Avenue

76198-13159 Kerman, Iran

Sources

1. Bermejo-Pareja F, Puertas-Martín V. Cognitive features of essential tremor: a review of the clinical aspects and possible mechanistic underpinnings. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2012; 2: pii. doi: 10.7916/ D89W0D7W.

2. Tröster A, Woods S, Fields JA et al. Neuropsychological deficits in essential tremor: an expression of cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathophysiology? Eur J Neurol 2002; 9(2): 143– 151.

3. Nasehi M, Ketabchi M, Khakpai F et al. The effect of CA1 dopaminergic system in harmaline-induced amnesia. Neuroscience 2015; 285 : 47– 59. doi: 10.1016/ j.neuroscience.2014.11.012.

4. Bermejo-Pareja F, Louis ED, Benito-León J et al. Risk of incident dementia in essential tremor: a population-based study. Mov Disord 2007; 22(11): 1573– 1580. doi: 10.1002/ mds.21553.

5. Abbassian H, Esmaeili P, Tahamtan M et al. Cannabinoid receptor agonism suppresses tremor, cognition disturbances and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat model of essential tremor. Physiol Behav 2016; 164(Pt A): 314– 320. doi: 10.1016/ j.physbeh.2016.06.013.

6. Macdonell RA. Cortical excitability and neurology: insights into the pathophysiology. Funct Neurol 2012; 27(3): 131– 145.

7. Kralic JE, Criswell HE, Osterman JL et al. Genetic essential tremor in gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor alpha1 subunit knockout mice. J Clin Invest 2005; 115(3): 774– 779. doi: 10.1172/ JCI23625.

8. Martin FC, Thu Le A, Handforth A. Harmaline-induced tremor as a potential preclinical screening method for essential tremor medications. Mov Disord 2005; 20(3): 298– 305. doi: 10.1002/ mds.20331.

9. Arshaduddin M, Al Kadasah S, Biary N et al. Citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor augments harmaline-induced tremor in rats. Behav Brain Res 2004; 153(1): 15– 20. doi: 10.1016/ j.bbr.2003.10.035.

10. Deuschl G, Elble RJ. The pathophysiology of essential tremor. Neurology 1999; 54 (11 Suppl 4): S14– S20.

11. Krahl SE, Martin FC, Handforth A. Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits harmaline-induced tremor. Brain Res 2004; 1011(1): 135– 158. doi: 10.1016/ j.brainres.2004.03.021.

12. Puschmann A, Wszolek ZK. Diagnosis and treatment of common forms of tremor. Semin Neurol 2011; 31(1): 65– 77. doi: 10.1055/ s-0031-1271312.

13. Ingwersen J, Aktas O, Kuery P et al. Fingolimod in multiple sclerosis: mechanisms of action and clinical efficacy. Clin Immunol 2012; 142(1): 15– 24. doi: 10.1016/ j.clim.2011.10.008.

14. English C, Aloi JJ. New FDA-approved disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis. Clin Ther 2015; 37(4): 691– 715. doi: 10.1016/ j.clinthera.2015.03.001.

15. Hemmati F, Dargahi L, Nasoohi S et al. Neurorestorative effect of FTY720 in a rat model of Alzheimer‘s disease: comparison with memantine. Behav Brain Res 2013; 252 : 415– 421. doi: 10.1016/ j.bbr.2013.06.016.

16. Nazari M, Keshavarz S, Rafati A et al. Fingolimod (FTY720) improves hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory deficit in rats following focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res Bull 2016; 124 : 95– 102. doi: 10.1016/ j.brainresbull.2016.04.004.

17. Kappos L, Radue E-W, O‘connor P et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362(5): 387– 401. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMoa0909494.

18. Becker-Krail D, Farrand AQ, Boger AH et al. Effects of fingolimod administration in a genetic model of cognitive deficits. J Neurosci Res 2017; 95(5): 1174– 1181. doi: 10.1002/ jnr.23799.

19. Kolasiewicz W, Kuter K, Wardas J et al. Role of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 1 in the harmaline-induced tremor in rats. J Neur Transm 2009; 116(9): 1059– 1063. doi: 10.1007/ s00702-009-0254-5.

20. Haghani M, Shabani M, Moazzami K. Maternal mobile phone exposure adversely affects the electrophysiological properties of Purkinje neurons in rat offspring. Neuroscience 2013; 250 : 588– 598. doi: 10.1016/ j.neuroscience.2013.07.049.

21. Shabani M, Larizadeh MH, Parsania S et al. Evaluation of destructive effects of exposure to cisplatin during developmental stage: no profound evidence for sex differences in impaired motor and memory performance. Int J Neurosci 2012; 122(8): 439– 448. doi: 10.3109/ 00207454.2012.673515.

22. Van Wijk N, Rijntjes E, Van De Heijning BJ. Perinatal and chronic hypothyroidism impair behavioural development in male and female rats. Exp Physiol 2008; 93(11): 1199– 1209. doi: 10.1113/ expphysiol.2008.042416.

23. Capoccia S, Maccarinelli F, Buffoli B et al. Behavioral characterization of mouse models of neuroferritinopathy. PloS One 2015; 10(2): e0118990. doi: 10.1371/ journal.pone.0118990.

24. Aghaei I, Arjmand S, Yousefzadeh Chabok S et al. Nitric oxide pathway presumably does not contribute to antianxiety and memory retrieval effects of losartan. Behav Pharmacol 2017; 28(6): 420– 427. doi: 10.1097/ FBP. 0000000000000311.

25. Razavinasab M, Shamsizadeh A, Shabani M et al. Pharmacological blockade of TRPV 1 receptors modulates the effects of 6-OHDA on motor and cognitive functions in a rat model of P arkinson‘s disease. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2013; 27(6): 632– 640. doi: 10.1111/ fcp.12015.

26. Vaziri Z, Abbassian H, Sheibani V et al. The therapeutic potential of Berberine chloride hydrate against harmaline-induced motor impairments in a rat model of tremor. Neurosci Lett 2015; 590 : 84– 90. doi: 10.1016/ j.neulet.2015.01.078.

27. Abbassian H, Whalley BJ, Sheibani V et al. Cannabinoid type 1 receptor antagonism ameliorates harmaline-induced essential tremor in rat. Br J Pharmacol 2016; 173(22): 3196– 3207. doi: 10.1111/ bph.13581.

28. Arjmand S, Vaziri Z, Behzadi M et al. Cannabinoids and tremor induced by motor-related disorders: friend or foe? Neurotherapeutics 2015; 12(4): 778– 787. doi: 10.1007/ s13311-0150367-5.

29. Cheng MM, Tang G, Kuo SH. Harmaline-induced tremor in mice: videotape documentation and open questions about the model. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2013; 3: pii. doi: 10.7916/ D8H993W3.

30. Du W, Aloyo VJ, Harvey JA. Harmaline competitively inhibits [3H] MK-801 binding to the NMDA receptor in rabbit brain. Brain Res 1997; 770(1– 2): 26– 29.

31. Kopecky BJ, Liang R, Bao J. T-type calcium channel blockers as neuroprotective agents. Pflügers Arch 2014; 466(4): 757– 765. doi: 10.1007/ s00424-014-1454-x.

32. Miwa H, Kondo T. T-type calcium channel as a new therapeutic target for tremor. Cerebellum 2011; 10(3): 563– 569. doi: 10.1007/ s12311-011-0277-y.

33. Dahmardeh N, Asadi-Shekaari M, Arjmand S et al. Modulation of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor ameliorates harmaline-induced essential tremor in rat. Neurosci Lett 2017; 653 : 376– 381. doi: 10.1016/ j.neulet.2017.06.015.

34. Egom EE, Kruzliak P, Rotrekl V et al. The effect of the sphingosine-1-phosphate analogue FTY720 on atrioventricular nodal tissue. J Cell Mol Med 2015; 19(7): 1729– 1734. doi: 10.1111/ jcmm.12549.

35. Tariq M, Arshaduddin M, Biary N et al. 2-deoxy-D-glucose attenuates harmaline induced tremors in rats. Brain Res 2002; 945(2): 212– 218.

36. Robertson HA. Harmaline-induced tremor: the benzodiazepine receptor as a site of action. Eur J Pharmacol 1980; 67(1): 129– 132.

37. Robertson HA. The benzodiazepine receptor: the pharmacology of emotion. Can J Neurol Sci 1980; 7(3): 243– 245.

38. Riba J, Valle M, Urbano G et al. Human pharmacology of ayahuasca: subjective and cardiovascular effects, monoamine metabolite excretion, and pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003; 306(1): 73– 83.

39. Asle-Rousta M, Kolahdooz Z, Oryan S et al. FTY720 (fingolimod) attenuates beta-amyloid peptide (Abeta42)-induced impairment of spatial learning and memory in rats. J Mol Neurosci 2013; 50(3): 524– 532. doi: 10.1007/ s12031-013-9979-6.

40. Balatoni B, Storch MK, Swoboda EM et al.FTY720 sustains and restores neuronal function in the DA rat model of MOG-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Res Bull 2007; 74(5): 307– 316. doi: 10.1016/ j.brainresbull.2007.06.023.

41. Doi Y, Takeuchi H, Horiuchi H et al. Fingolimod phosphate attenuates oligomeric amyloid β– induced neurotoxicity via increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in neurons. PloS One 2013; 8(4): e61988. doi: 10.1371/ journal.pone.0061988.

Labels

Paediatric neurology Neurosurgery Neurology

Article was published inCzech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

2018 Issue 6-

All articles in this issue

- Diagnostics, symptomatology and findings in diseases and disorders of the autonomic nervous system in neurology

- Patients with extensive early changes (ASPECTS < 5) – recanalization YES

- Patients with extensive early changes (ASPECTS < 5) – recanalization NO

-

Pacient s rozsiahlymi skorými zmenami (ASPECTS < 5) – rekanalizácia

Komentár ku kontroverziám - Pragnancy and multiple sclerosis from a neurologist’s point of view

- Quality of life of caregivers of patients with progressive neurological disease

- New-onset refractory status epilepticus and considered spectrum disorders (NORSE/ FIRES)

- The efficacy of cochlear implantation in adult patients with profound hearing loss

- Clinical results of cervical discectomy and fusion with anchored cage – prospective study with a 24-month follow-up

- A comparison of mini-invasive percutaneous versus classic open pedicle screw fixation of thoracolumbar fractures – retrospective analysis

- Dural reconstruction with usage of xenogenic biomaterial

- Meningococcal meningitis with Chiari malformation (type I)

- Fingolimod attenuates harmaline-induced passive avoidance memory and motor impairments in a rat model of essential tremor

- Comment to the article N. Dahmardeh et al. Fingolimod attenuates harmaline-induced passive avoidance memory and motor impairments in a rat model of essential tremor

- Evaluation of systolic and diastolic cardiac functions and heart rate variability in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

- Reconstruction of the anterior skull base with free muscle flap after iatrogenic injury

- A Bulgarian family with epileptic seizures as a first manifestation of familial cerebral cavernous malformations

- Solitary cerebellar metastasis of uterine cervical carcinoma

- Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Diagnostics, symptomatology and findings in diseases and disorders of the autonomic nervous system in neurology

- New-onset refractory status epilepticus and considered spectrum disorders (NORSE/ FIRES)

- Clinical results of cervical discectomy and fusion with anchored cage – prospective study with a 24-month follow-up

- Pragnancy and multiple sclerosis from a neurologist’s point of view

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career