-

Medical journals

- Career

Multiple Myeloma

Authors: R. Hájek 1,2,3; M. Krejčí 1; L. Pour 1; Z. Adam 1

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Internal Medicine – Hematooncology, University Hospital Brno, Czech Republic 1; Babak Myeloma Group, Department of Pathological Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic 2; Laboratory of Experimental Hematology and Cell Immunotherapy, Department of Clinical Hematology, University Hospital Brno, Czech Republic 3

Published in: Klin Onkol 2011; 24(Supplementum 1): 10-13

Overview

This manuscript is an introduction to the topic of multiple myeloma. Definition, incidence, etiology, pathogenesis and principles of diagnostics and treatment of multiple myeloma are described briefly in this work. It corresponds with Guidelines for diagnostics and treatment of the myeloma section of the Czech Hematological Society and the Czech Myeloma Group.

Key words:

multiple myeloma – diagnostics – treatment

This work was supported by projects of The Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: LC06027, MSM0021622434; grants of IGA of The Ministry of Health: NS10387, NS10406, NS10408 and grant of Czech Science Foundation GAP304/10/1395.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.Definition and Incidence

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant B-lymphoproliferative disease characterized by infiltration of pathological plasmocytes, osteolytic lesions in the skeleton and presence of monoclonal immunoglobulin (M-Ig) in serum and/or urine. MM comprises about 1% of all cancers but more than 10% of all hematooncological diseases. In the Czech Republic, the incidence of MM is 4/100,000. In Europe, more than 40,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. MM incidence is increasing with age; the median age at diagnosis is 65 [1].

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology of MM is still unclear. MM pathogenesis is a complex multifactorial process. Series of genetic changes in the cell lead to tumor transformation. It is known that there are changes in the microenvironment of the bone marrow allowing for tumor growth. At the same time, the function of the immune system is decreased. Patients are cytopenic and immunosuppressed as B-cells and later T-cells are defective [2]. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is a precancerosis that may lead to MM in a months or even years. Translocations of immunoglobulin gene (Ig) are present in most patients with MM; translocations of the heavy chain loci are described in 70% of cases and of light chain in 20% of cases. In MM patients, genome instability is typical. Cytogenetic analysis of MM cells shows frequent mutations and chromosomal aberrations. Aneuploidy is very common. There are reciprocal chromosomal translocations involving the IgH locus, chromosome 13 monosomy, loss of short arm of chromosome 17 and gains of the long arm of chromosome 1 and others [3]. Since several of these findings are connected to worse prognosis, FISH is performed to test for these [4]. Unlike other hematological malignancies, characterized by a limited number of genetic changes, MM is characterized by various changes; some of them are already used by clinicians as established prognostic markers [5]. Heterogeneity of MM seems to be related to molecular characteristics of the malignant clone [6]. There is also increasing knowledge about the role of cellular and molecular microenvironment of MM, angiogenesis and related factors, chemokines, etc. [7,8].

Diagnostics and Clinical Symptoms

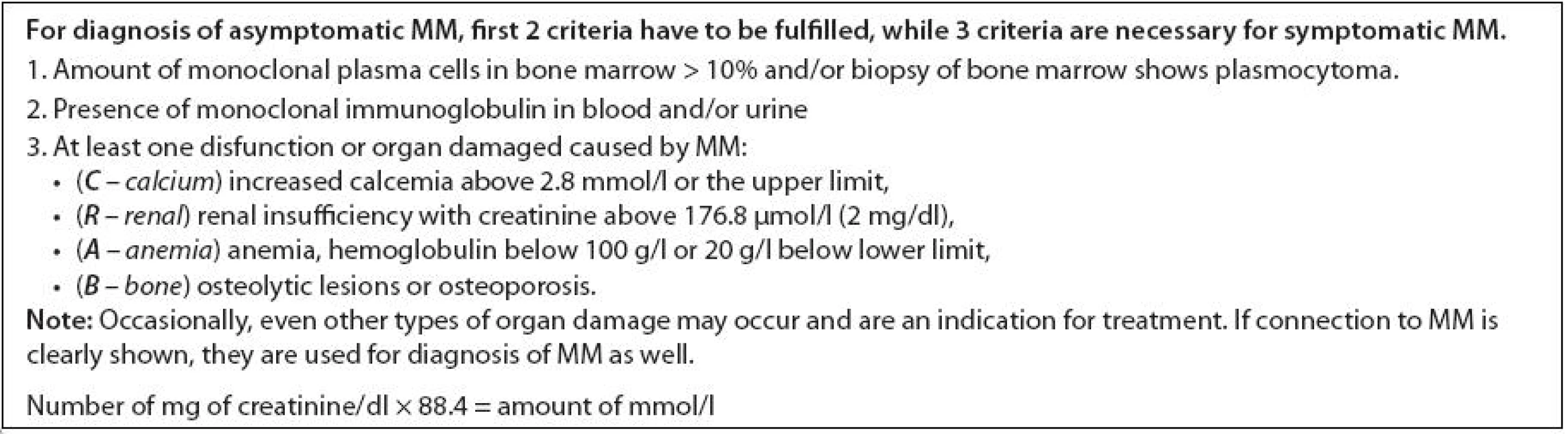

Diagnosis of MM is generally easily done based on typical morphology of the bone marrow (presence of more than 10% of clonal malignant plasmocytes), presence of monoclonal immunoglobulin in serum (mostly IgG and IgA) and/or in urine (light chains), as well as typical osteolytic lesions. Classical immunophenotype of malignant plasmocyte is CD19-56+38+138+. Clinical features are non-specific; most common are bone pain, especially pain in the spine, decreased immunity – recurrent and complicated infections, also features connected to infiltration of the bone marrow – fatigue and bleeding. Hypercalcemia is present in many patients as well as worsening kidney function. Bone involvement is typical, especially of long bones (femoral and humeral), skull and spine where multiple compressive fractures of vertebrae occur. Sometimes diffuse osteoporosis may be a sign of MM. In MM patients, total serum protein is usually elevated, sedimentation is increased and levels of physiological immunoglobulins are decreased. In certain cases, the disease may start as asymptomatic and may be diagnosed only after closer examination based on high sedimentation. For MM diagnosis and clinical staging, several classifications systems are currently used. Based on diagnostics criteria from 2003 [9], that are presented in Tab. 1, the differences between asymptomatic and symptomatic MM are defined. For symptomatic MM, the presence of clonal malignant plasmocytes in the bone marrow, presence of monoclonal immunoglobulin in serum and/or urine as well as presence of the following criteria are necessary: hypercalcemia (C), renal insufficiency (R), anemia (A), bone involvement (B). These criteria are called CRAB and are specified in Tab. 1. Any CRAB criteria present in the patient is a clear signal for treatment.

1. Diagnostic criteria of multiple myeloma based on IMWG, 2003.

Treatment

MM is still an incurable disease. Treatment is indicated in patients with symptomatic MM with presence of CRAB criteria. If the disease is sensitive to treatment, remission of various lengths is usually reached. Relapse or disease progression is common, and response to therapy in advanced disease is always worse. In MM treatment, combination of chemotherapy is used. Autologous transplantation of hematopoietic cells is especially important (indicated for patients younger than 65, symptomatic MM, in the first line of treatment). Radiotherapy is important mostly as palliative treatment, while analgesics as well as bisphosphonates are needed as supportive care. In some cases of MM, pathological verterbral fractures occur and spinal cord may be compressed. In these cases, urgent orthopedic and/or neurosurgical operations are needed. Since the 90s of the 20th century, clinical studies have shown that high-dose chemotherapy with support of autologous transplantation significantly increases complete remission and average survival in comparison to standard chemotherapy [10]. However, it is not curative since most patients relapse. This treatment possibility increases survival to more than 10 years for 20% of MM patients [11].

Development in MM treatment in the first decade of this century has been unprecedented. Our treatment strategy has been changed, and the best clinical protocols increase overall survival of more than 5 years for 80% of patients, while the intensity of treatment is lower and tolerance of treatment is higher [12,13]. This advancement is connected to three new highly efficient drugs – thalidomide, bortezomib and lenalidomide that have been implemented into our treatment protocols based on guidelines of the Myeloma section of the Czech Hematological Society and the Czech Myeloma Group, based on positive results from randomized clinical trials phase III [4]. All three drugs are available in the Czech Republic. They are usually combined with glucocorticoids or alkylating cytostatics (melphalan, cyclophosphamide) leading to increased efficiency. The good news is that treatment options are being increased almost daily. Several new highly efficient drugs (pomalidomide, carfilzomib, bendamustin), which will increase treatment options very soon, will play a key role in overcoming resistance to previous treatment or increase survival of patients. Moreover, many new drugs are being tested in phase I/II of clinical trials.

Ten years ago we left the concept of maintenance therapy with interferon alpha and thought it was a closed chapter forever [14]. Surprisingly, we are returning to this concept. Results of randomized trials with lenalidomide in maintenance therapy are extraordinary [15]. Almost two-fold increased time to next relapse cannot be explained by antitumor activity of the drug. It seems to be connected to the immunomodulatory properties of lenalidomide [16]. After safe interval between treatments is clarified, it will lead to the next advancement of prognosis of MM patients since keeping the disease in remission remained one of the key problems in treatment of MM.

Prognosis

Average length of life of untreated patients is 14 months; the median of survival on standard therapy is 3–4 years after diagnosis; transplantation protocols increased life to 6–7 years and about 20% of patients live longer than 10 years. Using the newest treatment protocols, life expectancy has been increased to 5 years for about 80% of patients and it is possible that in 30–40% of patients will survive more than 10 years. Unfortunately, about 10% of patients are high-risk, and the disease is newly active within a year, usually signaling worst prognosis. Following treatment may increase life expectancy no more than 2–5 years [4]. Many prognostic factors are used in MM: clinical (age, type of IgG paraprotein, absence of renal insufficiency, complete remission), conventional laboratory markers (albumin, beta2microglobulin, lactate dehydrogenasis, morphology of plasmoblasts, light chains, …), molecular biological markers (normal karyotype, presence of hyperdiploidy, risk gene panel etc). Detailed description of significance of each prognostic factor is beyond the scope of this text. Classical combination of beta2-microglobulin and albumin form the basis of the international staging system (ISS) based on Greipp [17]. MM patients are divided into 3 clinical stages that are significantly differ in survival – patients in 1 stage survive the longest (median 62 months), while patients in stage 3 survive the shortest (median 29 months). It seems that this simple prognostic staging system is valid even in the era of new drugs, although it is not perfect [18]. Predictive factors are being intensely studied that would be connected to treatment. Autologous transplantation seems to be the key advancement of the late 90s, while novel agents are the hit of the first decade of the 21st century. Maintenance therapy of lenalidomide may be the next key factor for increasing survival of MM patients.

Conclusion

In this introductory article of the supplementum dedicated to MM, we have introduced topics of clinical importance - diagnostics and therapy. Diagnostic criteria for MM, examinations necessary for MM diagnosis and therapeutic recommendations for MM were published in domestic and international journals repeatedly [4,19]. Prognosis of MM patients has improved exponentially after autologous transplantation and new therapy have been implemented. The difference between long-term survival in the 90s and nowadays (5% vs. 30–40%) is an unprecedented clinical advancement due to intensive research of the past decades. In the case of MM, one can clearly document the large benefit research has brought to treatment. This supplementum of Klinická onkologie has been dedicated to the methods of MM research. It is a pleasure and honor to write this introductory paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank all the patients and physicians of the Czech Myeloma Group, without whom this work would not be possible. We are also grateful to all researchers of the Babak Myeloma Group for their unending enthusiasm for their work.

Prof. MUDr. Roman Hájek, CSc.

Babak Myeloma Group

Department of Pathological Physiology

Faculty of Medicine

Masaryk University

Kamenice 5

625 00 Brno

Czech Republic

e-mail: r.hajek@fnbrno.cz

Sources

1. Adam Z, Bačovský J, Flochová E et al. Diagnostika a léčba mnohočetného myelomu. Doporučení vypracované Českou myelomovou skupinou, Myelomovou sekcí České hematologické společnosti a experty Slovenské republiky pro diagnostiku a léčbu mnohočetného myelomu. Transfuze Hematol Dnes 2005; 11 (Suppl 1): 3–50.

2. Raja KR, Kovarova L, Hajek R. Review of phenotypic markers used in flow cytometric analysis of MGUS and MM, and applicability of flow cytometry in other plasma cell disorders. Br J Haematol 2010; 149(3): 334–351.

3. Pichiorri F, Suh SS, Ladetto M et al. MicroRNAs regulate critical genes associated with multiple myeloma pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105(35): 12885–12890.

4. Hájek R, Adam Z, Maisnar V et al. Souhrn doporučení 2009 „Diagnostika a léčba mnohočetného myelomu“. Doporučení vypracované Českou myelomovou skupinou, Myelomovou sekcí České hematologické společnosti a experty Slovenské republiky pro diagnostiku a léčbu mnohočetného myelomu. Transfuze a hematologie dnes 2009; 15 (Suppl 3): 5–80.

5. Greslikova H, Zaoralova R, Filkova H et al. Negative prognostic significance of two or more cytogenetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma patients treated with autologous stem cell transplantation. Neoplasma 2010; 57(2): 111–117.

6. Munshi NC, Avet-Loiseau H. Genomics in multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17(6): 1234–1242.

7. Yaccoby S. Advances in the understanding of myeloma bone disease and tumour growth. Br J Haematol 2010; 149(3): 311–321.

8. Pour L, Svachova H, Adam Z et al. Levels of angiogenic factors in patients with multiple myeloma correlate with treatment response. Ann Hematol 2010; 89(4): 385–389.

9. International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol 2003; 121(5): 749–757.

10. Bladé J, Rosiñol L, Cibeira MT et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma beyond 2010. Blood 2010; 115(18): 3655–3663.

11. Novitzky N, Thomson J, Thomas V et al. Combined submyeloablative and myeloablative dose intense melphalan results in satisfactory responses with acceptable toxicity in patients with multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010; 16(10): 1402–1410.

12. Barlogie B, Anaissie E, van Rhee F et al. Reiterative survival analyses of total therapy 2 for multiple myeloma elucidate follow-up time dependency of prognostic variables and treatment arms. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(18): 3023–3027.

13. Attal M, Lauwers VC, Marit G et al. Maintenance treatment with lenalidomide after transplantation for MYELOMA: Final analysis of the IFM 2005–02. Proc ASH 2010: Abstract 310.

14. Adam Z, Ševčík P, Vorlíček J. Nádorová kostní choroba. 1. vyd. Praha: Grada 2005.

15. Attal M, Cristini C, Marit G et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after transplantation for myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(15s): Abstract 8018.

16. Zeldis JB, Knight R, Hussein M et al. A review of the history, properties, and use of the immunomodulatory compound lenalidomide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011; 1222(1): 76–82.

17. Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23(15): 3412–3420.

18. Munshi NC, Anderson KC, Bergsagel PL et al. Consensus recommendations for risk stratification in multiple myeloma: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 2. Blood 2011; 117(18): 4696–4700.

19. Engelhardt M, Udi J, Kleber M et al. European Myeloma Network: the 3rd Trialist Forum Consensus Statement from the European experts meeting on multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma 2010; 51(11): 2006–2011.

Labels

Paediatric clinical oncology Surgery Clinical oncology

Article was published inClinical Oncology

2011 Issue Supplementum 1-

All articles in this issue

- Editorial (CZ)

- Radiotherapeutic methods

- Multiple Myeloma

- Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undeterminated Significance: Introduction and Current Clinical Issues

- Sample Processing and Methodological Pitfalls in Multiple Myeloma Research

- Flow Cytometry in Monoclonal Gammopathies

- Flow Cytometric Phenotyping and Analysis of T Regulatory Cells in Multiple Myeloma Patients

- Genomics in Multiple Myeloma Research

- Polymorphisms Contribution to the Determination of Significant Risk of Specific Toxicities in Multiple Myeloma

- Oligonucleotide-based Array CGH as a Diagnostic Tool in Multiple Myeloma Patients

- Visualization of Numerical Centrosomal Abnormalities by Immunofluorescent Staining

- Impact of Nestin Analysis in Multiple Myeloma

- Editorial (EN)

- List of authors and reviewers

- Clinical Oncology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Multiple Myeloma

- Flow Cytometric Phenotyping and Analysis of T Regulatory Cells in Multiple Myeloma Patients

- Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undeterminated Significance: Introduction and Current Clinical Issues

- Flow Cytometry in Monoclonal Gammopathies

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career