-

Medical journals

- Career

Pleural exudate positive for paraprotein and free light chains as a very first sign of multiple myeloma

Authors: T. Franěk; R. Průša; M. Fořtová

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Medical Chemistry and Clinical Biochemistry, University Hospital Motol, Charles University, Second Faculty of Medicine, Prague

Published in: Klin. Biochem. Metab., 27, 2019, No. 2, p. 78-82

Overview

Objective: To describe a patient with pleural exudate in multiple myeloma and to show the importance of the examination of protein electrophoresis and free light chains (FLC) in the pleural effusion.

Design: Case report.

Settings: Department of Medical Chemistry and Clinical Biochemistry, University Hospital Motol, Charles University, Second Faculty of Medicine, V Úvalu 84, 150 06 Prague 5 (Czech Republic).

Material and Methods: Case report description.

Results: The paper describes a patient with multiple myeloma (IgG Lambda type) with pleural exudate, but without typical symptoms of multiple myeloma. There were found only paraprotein and elevation of FLC in serum, urine and pleural effusion, slightly increased serum β-2-microglobulin and lactate dehydrogenase. Diagnosis of multiple myeloma was confirmed by bone marrow biopsy.

Conclusion: This case highlights the differential diagnostic significance of paraprotein and FLC examination in pleural effusion of unclear aetiology.

Keywords:

free light chains – pleural exudate – electrophoresis – immunofixation

Introduction

Multiple myeloma is a malignant proliferation of plasma cells that affects predominantly bone marrow and skeletal system and constitutes approximately 10 % of all haematological malignancies [1,2].

Incidence of multiple myeloma in Czech Republic is 2.65 / 100 000 [3]. The pleural effusion is uncommon symptom of multiple myeloma. Only 6 % of patients with multiple myeloma are affected by pleural effusion and 0.8 % is caused by myelomatous pleural effusion [4-7].

The most common causes of pleural effusion associated with multiple myeloma are heart failure, renal fai-lure, nephrotic syndrome, hypoalbuminemia, effusions related to pneumonia, and amyloidosis [8].

Myelomatous pleural effusion is rarely associated with multiple myeloma and its diagnostic criteria were defined as follows: 1) a monoclonal protein in pleural fluid electrophoresis, 2) atypical plasmacytes in the pleural effusions, and 3) histological confirmation by a pleural biopsy or by an autopsy [1, 2]. These effusions may arise from either: extension of plasmacytomas of the chest wall, invasion from adjacent skeletal lesions, direct pleural involvement by myeloma (pleural plasmacytoma) or following lymphatic obstruction secondary to lymph node infiltration [1, 9-11].

Serum and urine protein electrophoretic analysis (and subsequent immunofixation) and free light chain (FLC) concentrations assessment are significant in the diagnosis and effectiveness of the treatment of multiple myeloma. Here, we focused on the significance of these examinations in pleural effusion in the diagnosis of multiple myeloma through a case report.

Case report

A 69-year old woman suffering from dyspnoea and intermittent pain of the chest was admitted to our hospital. She has lost 4 kg of weight within last six months. Her medical history included Caesarean section, ova-rian cyst surgery, arterial hypertension, and chronic venous insufficiency. Large right-sided pleural effusion was detected on the chest X-ray.

The basic biochemical examinations performed on admission were within reference range except the higher level of total serum protein (83.9 g/L, reference interval: 62.0 – 77.0 g/L). CRP was in reference range too, but the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was more than 100 mm/h. Red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets values in the blood count examination were also physiological.

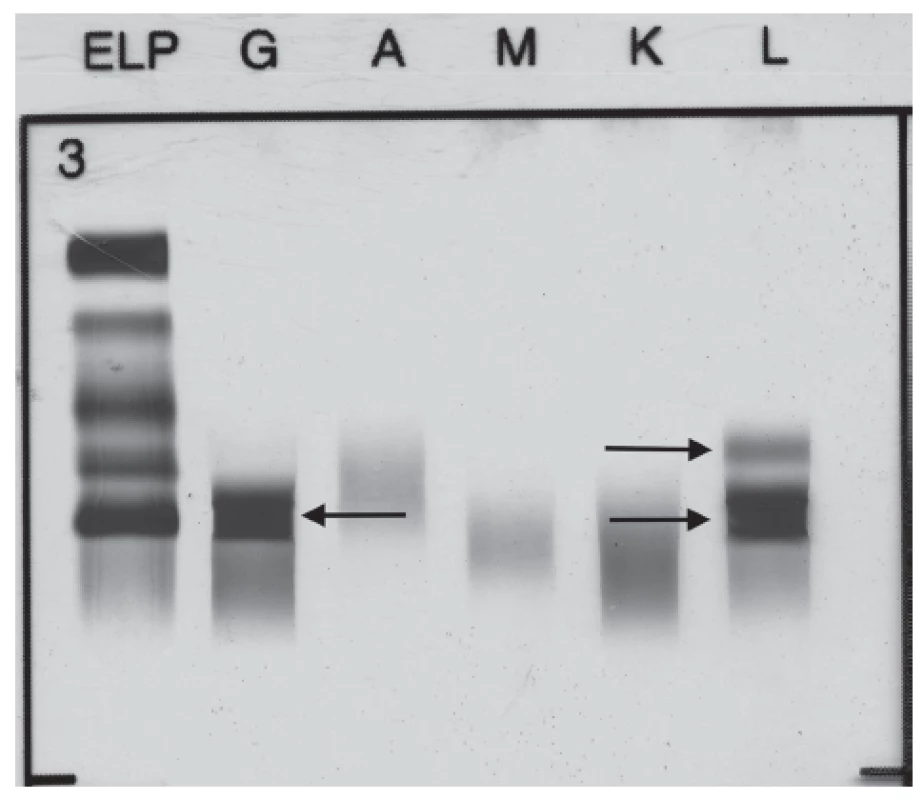

The broad laboratory examinations of this patient included tests for detection of monoclonal gammopathies. Serum protein electrophoresis showed hypoalbuminemia (39.4 %, reference interval: 55.8 – 66.1 %), hypergammaglobulinemia (29.7 %, reference interval: 11.0 – 18.8 %) with monoclonal band. Immunofixation performed from this sample showed the presence of monoclonal IgG Lambda 24.5 g/L and the band of FLC Lambda (Fig. 1). Serum level of FLC Kappa was less than 6 mg/L (reference interval: 3.3 – 19.4 mg/L), and FLC Lambda 332.5 mg/L (reference interval: 5.7 – 26.3 mg/L). FLC Kappa/Lambda ratio was < 0.018 (refe-rence interval: 0.26 – 1.65). The levels of serum immunoglobulins were as follows: IgG 31.6 g/L (reference interval: 6.7 – 15.0 g/L), IgA 0.74 g/L (reference interval: 0.90 – 3.70 g/L) and IgM 1.18 g/L (reference interval: 0.60 – 2.20 g/L). The level of serum β-2-microglobulin was 2.63 mg/L (reference interval: 1.00 – 2.30 mg/L) and serum lactate dehydrogenase 3.56 µkat/L (refe-rence interval: 1.67 – 3.17 µkat/L).

1. Immunofixation electrophoresis of patient´s serum sample presenting paraprotein IgG Lambda and FLC Lambda.

According to Light’s criteria [12], a pleural effusion was determined as exudate on the basis of following biochemical examination: total protein 46.3 g/L, albumin 25.7 g/L, lactate dehydrogenase 2.21 µkat/L, cholesterol 2.1 mmol/L (serum albumin was 35.9 g/L and cholesterol 5.3 mmol/L, the other serum parameters needed to evaluate the character of the effusion were mentioned above).

Microscopic examination of pleural effusion did not show typical signs of malignancy. A protein precipitate with lymphocyte infiltration and numerous polymorphonuclear cells were found in the cytoblock. Occasionally mesothelial cells were detected. The finding corresponded to florid inflammatory changes.

Pleural effusion flow cytometry finding cannot be unambiguously evaluated. Only a small number of mature B lymphocytes (1.8 % of the total number of cells), mostly without evidence of surface Ig light chains, were captured in the sample. The following cells were found in the sample: T lymphocytes (20.5 %), NKT lymphocytes (0.6 %) and NK lymphocytes without aberrant expression of the investigated traits (0.8 %), monocytes (10.7 %), granulocytes (approx. 52 %). It was not possible to decide whether this was a reactive B cell clone during another disease or unspecified B malignant disease.

The results of pleural fluid bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative.

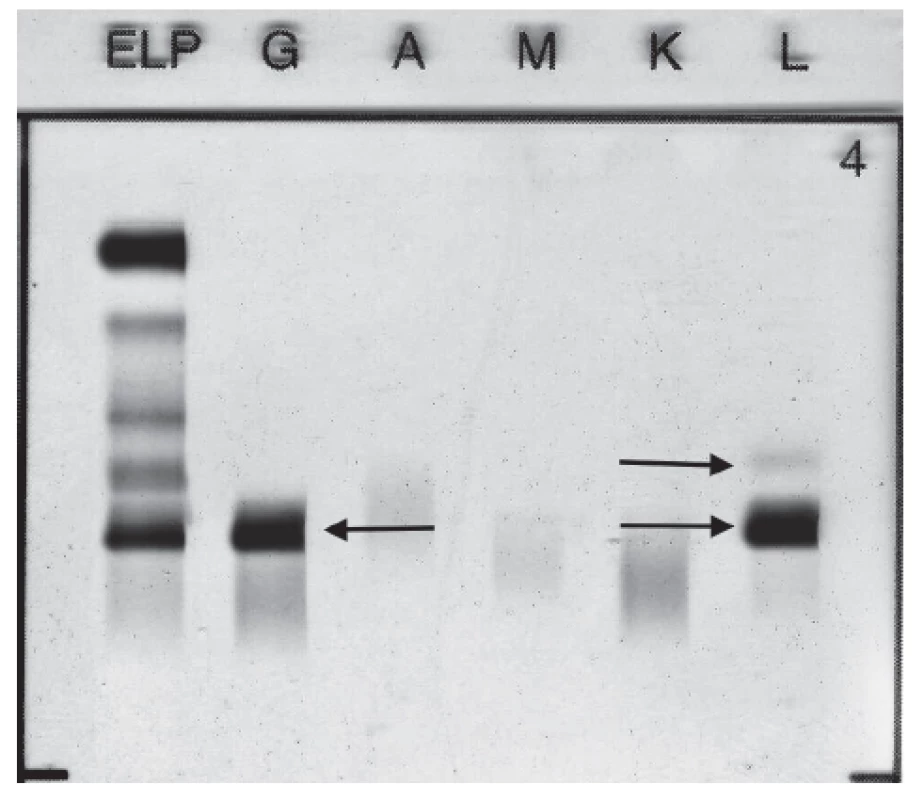

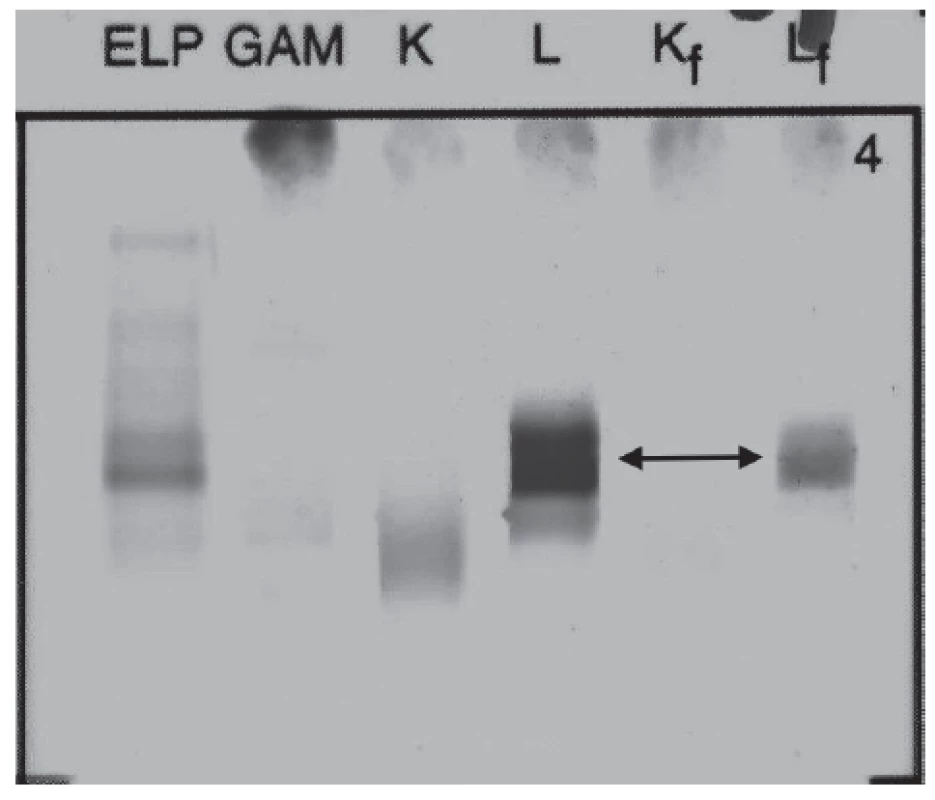

Standard electrophoretic analysis of the native pleural effusion showed the band migrating in the γ globulins zone. Immunofixation of pleural effusion detected presence of monoclonal IgG Lambda 11.5 g/L and FLC Lambda (Fig. 2). Quantitative analysis of FLC in pleural sample fluid showed level of FLC Kappa 28.5 mg/L, level of FLC Lambda 172.5 mg/L, FLC Kappa/Lambda ratio was 0.17.

2. Immunofixation electrophoresis of patient´s pleural fluid sample presenting paraprotein IgG Lambda and FLC Lambda.

Urine protein electrophoresis showed the presence of Bence-Jones protein Lambda (Fig. 3). Quantitative analysis of FLC in urine showed high level of FLC Lambda 68.9 mg/L (reference interval: 0.8 – 10.1 mg/L), level of FLC Kappa was 10.6 mg/L (reference interval: 0.4 – 15.1 mg/L), FLC Kappa/Lambda ratio was 0.15 (reference interval: 0.46 – 4.00). Proteinuria was 93 mg per day.

3. Immunofixation electrophoresis of patient´s urine sample presenting Lambda Bence-Jones protein.

Protein electrophoresis evaluations of serum, urine and pleural fluid were performed using the Hydrasys® electrophoresis system Sebia. Serum, urine and pleural concentrations of FLC were determined nephelometrically using the automatic analyzer Immage 800 (Beckman Coulter, reagents Binding Site). Serum concentrations of immunoglobulins were determined immunoturbidimetrically on the automatic analyzer Advia 1800 (Siemens, Dako).

Other biochemistry tests revealed the following pathological values in serum: CA 125 : 119.2 kU/L (re-ference interval 0 – 30 kU/L), NT-proBNP: 510.6 ng/L (reference interval: 20.0 – 125.0 ng/L).

An examination of a bone marrow biopsy showed the presence of more than 50 % plasmatic cells marked with CD 138 in their cytoplasmic membranes, with light-chains Lambda restriction. This finding corresponds to the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Bronchoscopic examination was also performed, with this result: without macroscopic and microscopic malignant changes. Pleural biopsy was not performed.

This patient did not have any of the CRAB features, it means: serum calcium was 2.2 mmol/L (re-ference interval: 2.05 – 2.40 mmol/L), ionized calcium 1.24 mmol/L (reference interval: 1.16 – 1.29 mmol/L), serum creatinine 52 µmol/L (reference interval: 42 to 80 µmol/L), eGFRCKD-EPI 1.57 mL/s/1.73 m2, red blood cell count 4.25 x 1012/L (reference interval: 3.80 – 5.20 x 1012/L), haemoglobin 128 g/L (reference interval: 120 – 160 g/L), without osteolytic bone lesions (X-ray of the cranium, spine, pelvis, upper and lower limbs; MRI of the cranium and spine; CT of the chest were performed).

A gynaecological examination was performed due to increased level of CA 125, and its conclusion was: benign ovarian cyst, otherwise normal finding. Echocardiography was supplemented due to increased NT-proBNP, its finding was normal. However, the CT scan showed a slight cardiomegaly. The findings on the other organs (brain, breast, organs of the chest and abdomen) were normal, without evidence of any tumour using MRI, CT and mammography examinations.

Discussion

In the case of our patient, we cannot unequivocally determine whether the pleural effusion was the exudate of a truly myelomatous origin or the exudate only associated with multiple myeloma diagnosis.

A pleural biopsy that would be needed to confirm the diagnosis of myelomatous pleural effusion was not performed. Microscopic examination of pleural effusion showed only inflammatory, not tumorous, changes. Nevertheless, flow cytometry of pleural effusion did not exclude the presence of B malignant disease.

We found the monoclonal protein IgG Lambda and both FLC Kappa and FLC Lambda in pleural fluid, which would suggest for myelomatous character of pleural effusion. However, the IgG Lambda and FLC Lambda concentrations in the pleural fluid were approximately half that of serum (11.5 vs. 24.5 g/L and 172.5 vs. 332.5 mg/L). It is reported in the literature [6, 8] that, on the contrary, a higher value of paraprotein in pleural effusion compared with serum is typical for myelomatous pleural effusion, which suggested for a local synthesis of paraprotein in pleural fluid. The conclusion of these studies was that myelomatous pleural effusion could be characterized by an absolute paraprotein value which is much higher than that in the serum. These facts raise the question of whether it was not a passive diffusion of paraprotein from the blood in our case report. On the other hand, a higher concentration of FLC kappa was found in pleural effusion of our patient in comparison with serum (28.5 mg/L vs. less than 6 mg/L). This may be indicative for either local (reactive or malignant) lymphocyte/plasmacyte synthesis or different clearance mechanism in the pleural fluid and in the blood [6].

The pleural effusion of our patient was the exudate, thus excluding heart failure, chronic renal failure, nephrotic syndrome and hypoalbuminemia reasons of its origin [8]. A slight form of heart failure (with slight cardiomegaly on the CT scan and NT-proBNP 510.6 ng/L) could have hypothetically contributed to the pleural fluid formation. However, NT-pro BNP cut-off value (when fluidothorax of cardiac aetiology is formed) is most commonly reported as 1500 ng/L. Most often, exudate is of inflammatory, infectious, or cancerous ori-gin [13]. Infectious character of exudate was excluded using microbiological examination.

We also considered the relationship to the ovarian pathology with elevated CA 125 in differential diagnosis of right-sided pleural effusion of our patient. Right-si-ded pleural effusion is typical for Meigs syndrome or for atypical Meigs syndrome. Meigs syndrome is triade of ascites, right-sided pleural effusion and benign ovarian tumor (ovarian fibroma, fibrothecoma, Brenner tumor and occasionally granulosa cell tumour), atypical Meigs syndrome is characterized by benign pelvic mass with right-sided pleural effusion but without ascites. Because the transdiaphragmatic lymphatic channels are larger in diameter on the right, the pleural effusion is classically on the right side. Ascitic fluid and pleural fluid in Meigs syndrome can be either transudative or exudative. Both of these syndromes were excluded because our patient had no benign tumor but the ovary cyst and had no ascites [14].

The presence of an IgA paraprotein is most commonly associated with myelomatous pleural effusions (in up to 80 % cases in some studies) [1, 10, 11].

Our reported patient had an underlying IgG paraprotein in pleural effusion. IgG paraprotein associated with myelomatous pleural effusion has been described in the case report of Miller et al. [11]. This was a 66-year old woman with already diagnosed multiple mye-loma treated with chemotherapy. On this therapy she remained 8 months in remission. Subsequently, a large right-sided pleural effusion developed. Unlike our patient, there was a marked right-sided pleural thickening on CT scan and positive cytology of pleural effusion with the presence of plasma cells. Histology from pleural biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of pleural plasmacytoma (in our case, pleural biopsy was not performed). Unlike us, in this case report, paraprotein was examined only in serum (not in the pleural effusion as in our case).

In our patient, pleural effusion was the first sign of multiple myeloma, causing dyspnoea and chest pain. This patient had no organ disorders typical for myeloma or thickening of the pleura on CT examination. We found only paraprotein and elevation of FLC in serum, urine and pleural effusion, slightly increased serum β-2-microglobulin and lactate dehydrogenase and diagnosis was confirmed by bone marrow biopsy.

Bilateral pleural effusion as an initial manifestation of multiple myeloma (IgD type) without affecting of other organs was described by Jiang et al. in their case report [15]. In this patient, pleural fluid cytology revealed atypical plasma cells. These authors did not assess paraprotein and FLC in pleural fluid.

Turkish authors [7] examined serum, pleural fluid and urine immunofixation electrophoresis in 56 years old man with left pleural effusion. They found IgG Kappa paraprotein in serum and pleural fluid and the Bence-Jones protein in urine. Pleural biopsy showed plasmacyte infiltration and bone marrow biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Complete regression of the pleural effusion was achieved after one round of chemotherapy.

The adjacent finding in our patient was increased tumour marker CA 125 in serum. This elevation could have been due to proven non-malignant ovarian cyst or to the affection of the pleura in the presence of pleural effusion. It has been reported in myelomatous pleural effusion [16] and its presence in serum might raise the concern for this effusion [17]. Elevated CA 125 is very common in patients with effusions [18]. In the case report of Wang et al. [18], there were no specific traits of pleural effusion in patient with multiple myeloma, except for elevated serum CA 125 levels. The development of myelomatous pleural effusion and increased serum CA 125 due to this diagnosis is associated with poor prognosis [11, 16, 17, 18].

This detailed analysis shows that the aetiology of pleural exudate in our patient was not clear. Chemotherapy was started after determining of the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. The outcome is not yet available.

Conclusion

This case report describes the extremely rare case of a patient with multiple myeloma presenting with pleural effusion only as the first sign of multiple myeloma (clinically presented as dyspnoea and chest pain). All examinations typical for the multiple myeloma were negative, except of the bone marrow biopsy, presence of the paraprotein and FLC in serum, urine and pleural effusion, and elevated CA 125.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Do redakce došlo: 12. 2. 2019

Adresa pro korespondenci:

MUDr. Tomáš Franěk, Ph.D.

Ústav lékařské chemie a klinické biochemie 2. LF UK a FN Motol

V Úvalu 84

150 06 Praha 5

e-mail: tomas.franek@fnmotol.cz

Sources

1. Rodríguez, J. N., Pereira, A., Martínez, J. C., Conde, J., Pujol, E. Pleural effusion in multiple myeloma. Chest, 1994, 105 (2), p. 622–624.

2. Natori, K., Izumi, H., Nagase, D., Fujimoto, Y., Ishihara, S., Kato, M., Umeda, M., Kuraishi, Y. IgD mye-loma indicated by plasma cells in the peripheral blood and massive pleural effusion. Ann. Hematol., 2008, 87 (7), p. 587–589.

3. http://www.myeloma.cz/index.php?pg=mnohocetny-myelom--zakladni-udaje--statistika (accessed 11. 08. 2015).

4. Kintzer, J. S., Rosenow E. C., Kyle R. A. Thoracic and pulmonary abnormalities in multiple myeloma. A review of 958 cases. Arch. Intern. Med., 1978, 138 (5), p. 727–730.

5. Alexandrakis, M. G., Passam, F. H., Kyriakou, D. S., Bouros D. Pleural effusions in hematologic malignancies. Chest, 2004, 125 (4), p. 1546–1555.

6. Tsukamoto, A., Yoshiki, Y., Yamazaki, S., Kumano, K., Nakamura F., Kurokawa M. The significance of free light chain measurements in the diagnosis of myelomatous pleural effusion. Ann. Hematol., 2014, 93 (3), p. 507–508.

7. Uskül, B. T., Türker, H., Emre Turan, F., Unal Bayraktar, O., Melikoğlu, A., Tahaoğlu C, Oz, B. Pleural effusion as the first sign of multiple myeloma. Tuberk. Toraks., 2008, 56 (4), p. 439–442.

8. Oudart, J. B., Maquart, F. X., Semouma, O., Lauer, M., Arthuis-Demoulin, P., Ramont L. Pleural effusion in a patient with multiple myeloma. Clin. Chem., 2012, 58 (4), p. 672–674.

9. Gogia, A., Agarwal, P. K., Jain S., Jain K. P. Mye-lomatous pleural effusion. J. Assoc. Physicians India, 2005, 53, p. 734–736.

10. Yokoyama, T., Tanaka, A., Kato, S., Aizawa, H. Multiple myeloma presenting initially with pleural effusion and a unique paraspinal tumor in the thorax. Intern. Med., 2008, 47 (21), p. 1917–1920.

11. Miller, J., Alton, P. A. Myelomatous pleural effusion-A case report. Respir. Med. Case Rep., 2012, 5, p. 59–61.

12. Light, R. W., McGregor, M. I., Luchsinger, P. C., Ball, W. C. Pleural effusions: The diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann. Intern. Med., 1972, 77 (4), p. 507–513.

13. Marel, M. Doporučený postup diagnostiky a léčby fluido-toraxu. Aktualizace 2016. Accessible on www. pneumologie.cz/upload/1480180128.pdf.

14. Morán-Mendoza, A., Alvarado-Luna, G., Calderillo-Ruiz, G., Serrano-Olvera, A., López-Graniel, C. M., Gallardo-Rincón, D. Elevated CA125 level associated with Meigs’ syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer., 2006, 16 (1): p. 315–318.

15. Jiang, A. G., Yang, Y. T., Gao, X. Y., Lu, H. Y. Bila-teral pleural effusion as an initial manifestation of multiple myeloma: A case report and literature review. Exp. Ther. Med., 2015, 9 (3), p. 1040–1042.

16. Xu, X. L., Shen, Y. H., Shen, Q., Zhou, J. Y. A case of bilateral pleural effusion as the first sign of multiple mye-loma. Eur. J. Med. Res., 2013, 18 (7), p. 1–4.

17. Suwatanapongched, T., Pornsuriyasak, P., Kanoksil, W., Morasert, T., Virayavanich, W. A. 76-year-old man with anemia, bone pain, and progressive dyspnea. Chest, 2014, 145 (4), p. 913–918.

18. Wang, Z., Xia, G., Lan, L., Liu, F., Wang, Y., Liu, B., Ding, Y., Dai, L., Zhang, Y. Pleural effusion in multiple myeloma. Intern. Med., 2016, 55 (4), p. 339–345.

Labels

Clinical biochemistry Nuclear medicine Nutritive therapist

Article was published inClinical Biochemistry and Metabolism

2019 Issue 2-

All articles in this issue

- Vysoce citlivé (hs) kardiální troponiny. Pomníček velkému úsilí, které tak hned neustane.

- Comparison of troponin I (Abbott, Beckman Coulter, Siemens) and troponin T (Roche) high-sensitivity measurement results

- Role of rs17817449 FTO gene polymorphism in patients with type 1. diabetes in terms of obesity and diabetes control

- Fatty acid elongases and their involvement in the pathogenesis of disease states

- POCT system for the fecal calprotectin detection in the tele-monitoring of patients with inflammatory bowel disease

- Changes in urinary and serum markers of renal injury in adult patients after angiographic contrast medium administration

- Rare pyrophosphate renal stone in 5 years old boy with congenital hypophosphatasia

- Pleural exudate positive for paraprotein and free light chains as a very first sign of multiple myeloma

- Clinical Biochemistry and Metabolism

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Comparison of troponin I (Abbott, Beckman Coulter, Siemens) and troponin T (Roche) high-sensitivity measurement results

- POCT system for the fecal calprotectin detection in the tele-monitoring of patients with inflammatory bowel disease

- Changes in urinary and serum markers of renal injury in adult patients after angiographic contrast medium administration

- Fatty acid elongases and their involvement in the pathogenesis of disease states

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career