-

Medical journals

- Career

Does working in education affect teachers’ auditory threshold?

Authors: P. Sachová 1,3; E. Mrázková 2,3,4; H. Kollárová 1; K. Vojkovská 2,3; J. Fluksová 2; Z. Nakládal 5; V. Janout 1,2

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Palacký University Olomouc Head Ass Prof Helena Kollárová, MD, PhD 1; Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ostrava Head Prof Vladimír Janout, MD, PhD 2; Center for Hearing and Balance Disorders Head Physician Eva Mrázková, MD, PhD 3; Ear, Nose and Throat Department, Havířov Hospital Head Physician Eva Mrázková, MD, PhD 4; Regional Public Health Authority of the Olomouc Region, Olomouc Director Zdeněk Nakládal, MD, PhD 5

Published in: Pracov. Lék., 68, 2016, No. 4, s. 125-131.

Category: Original Papers

Overview

Hearing loss is a disability; although invisible, it has a significant negative impact on an individual’s quality of life. A regular screening of threshold of hearing in teachers is a challenge of today. During class, teachers are exposed to noise from pupils as well as to background noise (air conditioning, heating, ventilation or traffic). For teachers with any hearing loss, teaching becomes more difficult as they make efforts to listen and understand. The job of a teacher is very demanding, especially from the psychological point of view.

The objectives of the study were to compare auditory threshold levels between nursery (NS) and primary school (PS) teachers and controls exposed to occupational noise and to answer the question of whether school noise may have a negative impact on teachers’ hearing.

Materials for this study were obtained from research in nursery and elementary schools in Ostrava Poruba. An examination of teachers’ hearing by audiometry (232 respondents) is parts of the research. The control group was made by respondents of grant study IGA MZ ČR NT12246-5/2011 – Epidemiologic and genetics study of frequency of hearing defects. Probands were women who worked in the risk of noise for their whole lives (1,133 respondents).

Statistical testing proved deteriorating of threshold of hearing of teachers with the length of their practice which, however, highly correlated with their age. Teachers at the nursery school had the best threshold of hearing, even though in the questionnaire research in 95% they stated they felt problems with hearing. The control group (population exposed to noise in working environment) showed significantly higher losses of hearing. At the highest examined frequencies, the oldest category (practice of the profession longer than 30 years) had losses of hearing worse by 20 dB than the group of teachers.

The research did not prove the original hypothesis that assumed that noise produced in the school environment might have a negative effect on the hearing of educational workers.KEYWORDS:

teacher – loss of hearing – noise – nursery school – primary schoolINTRODUCTION

Hearing loss is a disability, although invisible, it has a significant negative impact on an individual’s quality of life. Hearing damage may vary in severity, ranging from a slight hearing impairment to practically complete deafness. The more severe the impairment has the more profound effects on a person’s everyday life (nervousness, irritability, communication-related frustration, mental problems and, eventually, social isolation). Hearing loss is partly due to the physiological processes associated with ageing of the organism (presbyacusis), apart from that, it is influenced by numerous other factors [1, 2, 4, 7, 8]. The most significant factor is noise, in particular occupational noise exposure. Although teaching is not listed as a high-risk profession, foreign studies have shown that during class, teachers are exposed to high-risk levels of acoustic pressure [13, 15, 18]. A Polish study found that during break time, the most frequent noise level was 86 dB, reaching 95–98 dB in some parts of schools. During physical education lessons, noise levels commonly exceeded 90 dB. For teachers, the mean daily exposure during an 8-hour working day (LAeq8h) was 80 dB, sometimes even 85 dB [14]. Long-term exposure to school noise is likely to result in hearing damage in both teachers and pupils.

During class, teachers are exposed to noise from pupils as well as to background noise (air conditioning, heating, ventilation or traffic). For teachers with any hearing loss, teaching becomes more difficult as they make efforts to listen and understand. Thus, hard of hearing persons need to concentrate a lot to keep pace with their pupils, spending a lot of effort [9, 16].

The objectives of the study were to compare auditory threshold levels between nursery (NS) and primary school (PS) teachers and controls from the Karviná region exposed to occupational noise and to answer the question of whether school noise may have a negative impact on teachers’ hearing. The study was a part of Czech Ministry of Health grant agency project no. NT12246-5/2011 called An Epidemiological and Genetic Study of the Frequency of Hearing Impairment.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study evaluated hearing educationalists was carried out in the Ostrava city borough of Poruba in 2011–2013. The sample comprised nursery (NS) and primary (PS) school teachers. All 19 NSs in the borough took part in the study. A total of 11 ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialists from the towns of Orlová, Karviná, Havířov and Bohumín were involved in the study.

The course of all examinations was standardized, consisting of completion of a preset questionnaire and an objective hearing test performed by an ENT specialist. The questionnaire comprised identification items (age and gender), family history and information on respondents’ health status and self-assessed hearing abilities. It also focused on their occupational history. The respondents were asked about the type of occupation, length of service, exposure to occupational noise, use of personal protective equipment and its type. The risk of occupational noise, however, was not specifically defined and was only subjectively assessed by respondents. Each auditory threshold assessment using pure tone audiometry was preceded by an otoscopic examination. In ENT specialists’ offices, participants were examined with a diagnostic audiometer in a quiet room. In the school setting, hearing was tested with the Smart 130 diagnostic audiometer, always in the quietest room of the building. In two randomly selected respondents from each school, the auditory threshold was verified by tests in an ENT office quiet room and did not differ from the obtained data (a noise level below 20 dB, standardized test conditions). The obtained data were automatically plotted as air conduction threshold curves, separately for the left and right ears, at the commonly predefined frequencies (125, 250, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, 3000, 4000, 6000 and 8000 Hz).

To report the data, basic descriptive statistics was used (the arithmetic mean, standard deviation and frequency tables). The obtained data were compared with those in the control group using a paired t-test. To assess the obtained data at individual frequencies depending on the length of service (categories), the analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. The dependence between the length of service and age was measured with the Pearson correlation coefficient (r). The level of significance of the statistical tests was set at 5%. The statistical analyses were carried out using the Stata v. 10 statistical software package.

Sample characteristics

All 19 NSs in the aforementioned borough took part in the study. A total of 12 PSs were approached, of which 6 agreed to participate; the reason for not participating was teachers’ unwillingness to do so, mainly due to a lack of time. Out of 315 teachers approached, 253 respondents took part (the other teachers were not present at work on the day of survey), a response rate of 80.3%. From the total of 253 teachers, twenty-one were excluded prior to statistical analyses. Firstly, only 18 males (7.8%) participated so all of them were excluded and only females were analyzed to increase the validity of the study as it has been statistically proven that hearing tends to deteriorate faster in males. [6, 9, 10] The other three respondents were excluded due to their asymmetrical hearing loss. The group comprised PS teachers (100 respondents) and NS teachers (132 respondents), with a mean age of 45.8 and 47.1 years, respectively.

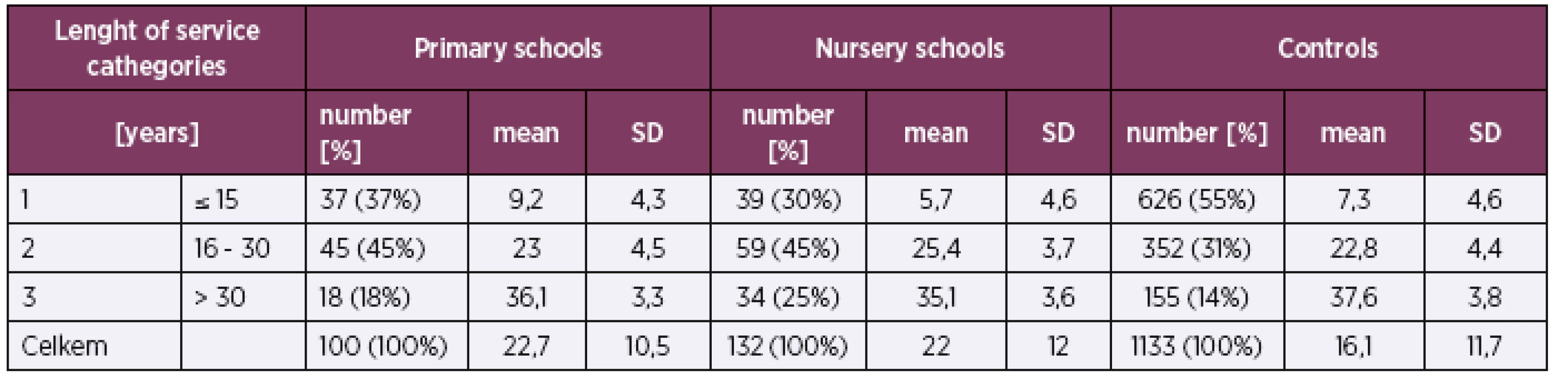

The controls were persons who sought ENT examination for acute disease throughout the Karviná region between September 2011 and December 2014. Over the period, a total of 13,738 people (6448 males and 7290 females) were treated by the cooperating ENT specialists. To compare their quality of hearing with that in teachers, two criteria for inclusion in the control group were set. First, only female controls were included as the teacher groups were also comprised exclusively of females. The second criterion was exposure to noise throughout the entire professional career. After the criteria were applied, 1485 females remained in the control group that is 11% of the original sample. Then, to obtain reliable auditory threshold for workers at risk for exposure to noise, included in the study were only individuals with perceptive hearing loss, negative otoscopic findings, no history of previous hearing impairment, no recurrent otitis media, acoustic trauma or sudden hearing loss or asymmetrical hearing loss. As a result, another 352 respondents had to be excluded. Eventually, the number of controls dropped to 1133 (Table 1). Their mean age and length of service were 60.0 years and 16.4 years, respectively. The largest subgroup was 314 manual workers (31%). Only 16 controls were teachers. The vast majority of all participants were non-smokers (71% of teachers and 64% of controls).

1. Sample characteristics

*SD – Standard Deviation Data obtained from NS and PS teachers and their controls were used to calculate their correlation coefficients (for NSs: r = 0.807; for PSs: r = 0.748) and linear regression functions (for NSs: y = 0.801x – 17.85; for PSs: 0.754x – 16.58). Given the strong correlation between the age and length of service, the subsequent data were processed with respect to the length of service (see Table 1).

RESULTS

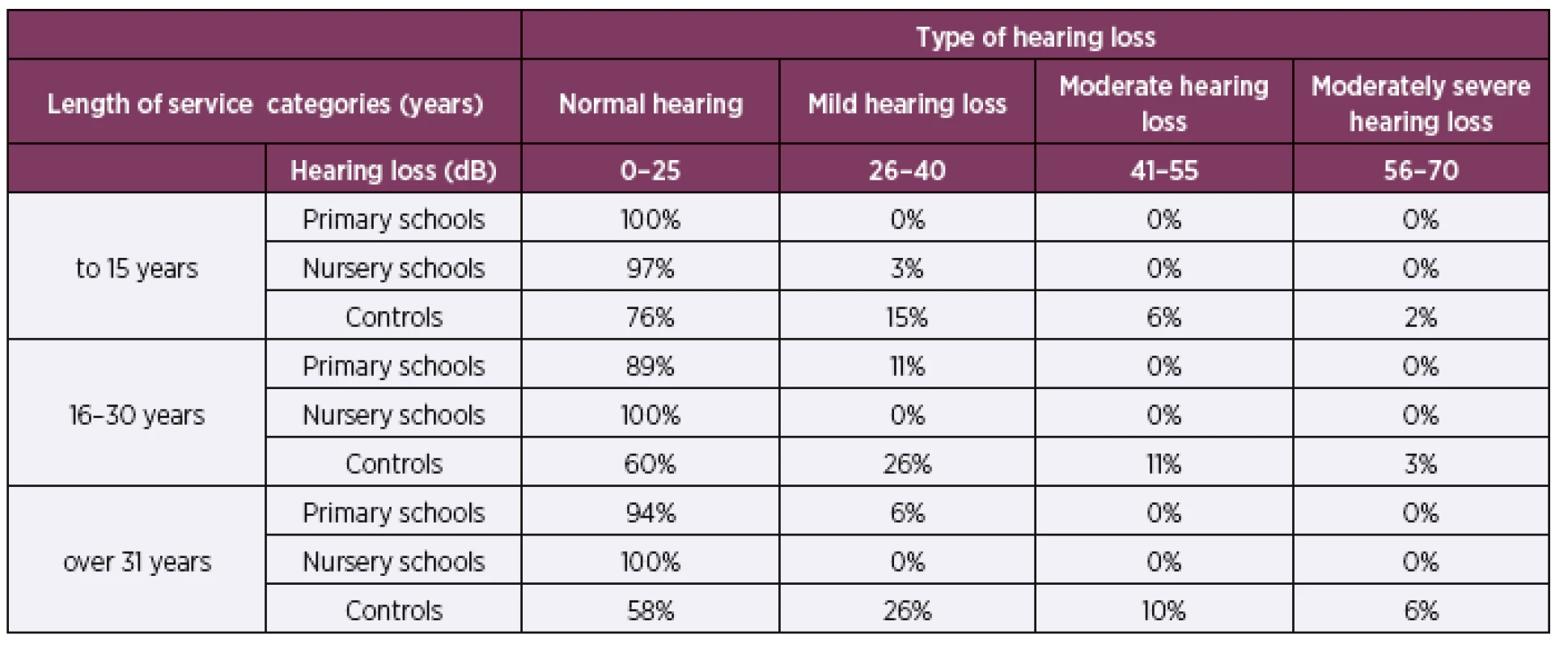

Assessing the degree of hearing impairment

Generally, assessment of the auditory threshold according to the WHO [3, 5] showed that across all teachers’ length of service categories, the best results were observed in NS teachers (Table 2). The vast majority of them had a normal auditory threshold (up to 20 dB hearing loss); only 3% of these females were found to have mild hearing loss. None of these teachers suffered from moderate, severe or profound impairment. The opposite was true for the controls, with 15% of relatively young respondents (length of service ≤ 15 years) suffering from mild hearing loss. The prevalence of hearing loss increased with the length of occupational noise exposure (see Table 2).

2. Prevalence of hearing loss with respect to respondents’ length of service

Comparing the auditory threshold between teachers and controls

The audiograms below suggest that both NS and PS teachers included in the study had a normal auditory threshold. Impairment of the auditory threshold was mainly noted at the highest frequencies (6000 Hz and 8000 Hz). Teachers with more than 30 years of service had a hearing loss of no more than 30 dB at 8000 Hz. At frequencies between 500 and 4000 Hz, most important for understanding speech and human communication, teachers had a normal auditory threshold (up to 20 dB hearing loss) despite their long service in education.

Hearing loss was more prominent in the controls, respondents who, according to their self-assessment, were exposed to occupational noise throughout their professional life. The normal auditory threshold was only found in those with the shortest exposure at low frequencies; the others had an impaired auditory threshold. Even respondents in the first category (up to 15 years of service) had notable hearing loss of 37 dB at the highest frequencies (6000 Hz and 8000 Hz). With an increasing length of service, a decrease in the auditory threshold interfering with the understanding of human speech was observed.

Similarly, an increasing length of teachers’ occupational exposure was found to be associated with a linear impairment in the auditory threshold in teachers. Over the first 15 years of service, the auditory threshold decreased by a mean of 6 dB, 3 dB and 12 dB in PS teachers, NS teachers and controls, respectively (Figures 1–3).

Figure 1. Hearing loss in participants with up to 15 years of service

Figure 2. Hearing loss in participants with 16–30 years of service

Figure 3. Hearing loss in participants more than 30 years of practice

DISCUSSION

Hearing damage is one of the most common types of sensory impairments. Its main causes in adults are age-related hearing loss and exposure to noise [1]. It is a well-known fact that from one’s 20s onward, auditory acuity gradually decreases. Hearing impairment at high frequencies develops, associated with reduced speech intelligibility [17]. Hearing loss related to both age and length of service was confirmed in both female teachers and the control group comprising noise-exposed females from the Karviná region. Even though the greatest hearing loss, namely 34 dB at 8000 Hz, was seen in teachers aged 51 to 70 years (i. e. more than 30 years of service), no impairment of the auditory threshold due to noise exposure was found. Given the age, the values are still in the normal range. Similarly, controls’ threshold curves also showed age-related decreases at high frequencies, albeit statistically significantly higher than those in teachers (49 dB at 8000 Hz).

The present study compared teachers’ auditory thresholds with those in respondents exposed to occupational noise as foreign studies have shown that noise levels encountered mainly by industrial workers may be also experienced by teachers in classrooms [13, 14, 15, 18]. They often complain of dizziness, tinnitus, hearing difficulties, irritability, problems with sleep or concentration and other symptoms potentially related to noise [19]. However, results of the present study showed that both NS and PS teachers of all age categories had lower hearing loss at all frequencies tested than noise-exposed workers in the control group. Moreover, none of the teachers suffered from moderate, severe or profound impairment and the proportion of respondents with mild hearing impairment among all teachers was 11.2%. This suggests a lower prevalence of hearing impairment than that reported by Brazilian authors stating that 25% of teachers had some hearing loss found on audiometric examination [17]. Unlike the present study, however, theirs included males (14%) as well. Males were excluded from the present study prior to statistical analyses because of their small number (only 7.8% of the sample) and the study focused on female respondents as they account for the vast majority of school workers [2, 16, 21]. In the Moravian-Silesian Region, there were 6908.5 PS teachers (84.9% of females) and 3217.9 NS teachers (99.4% females) in the 2012/2013 school year (full-time equivalent) [11]. Females have been shown to lose their hearing more slowly than their age-matched male counterparts [6, 10, 20].

Compared to teachers, noise-exposed respondents were found to have significantly decreased auditory thresholds at frequencies from 6000 Hz to 8000 Hz as early as after 16 years of occupational noise exposure. It is the decrease at high frequencies that is considered to be caused by exposure to noise [4]. Its effects on the auditory apparatus are usually manifested after long exposure, namely 10 to 15 or even more years for higher noise levels [2]. The effects are better seen from hearing loss assessment in the present study, with a higher percentage of noise-exposed respondents with more than 31 years of service having worse auditory thresholds that teachers.

More evidence on the effect of noise on exposed workers was presented by a study carried out in textile workers in India. Those were cotton ginning workers exposed to acoustic pressure levels ranging from 89 dB to 106 dB. Pure tone audiometry assessment showed that the prevalence rates of hearing loss of more than 25 dB were 94% and 97% for high and low frequencies, respectively. The analyses also showed that hearing loss was significantly associated with length of noise exposure [6]. In the present group of noise-exposed workers, hearing loss was related to age and thus to the length of exposure. Compared to the Indian study, the prevalence of hearing impairment was lower, even in the oldest age category (51 to 70 years of age; 37.7%).

Consistently with the above studies, the present results confirmed the well-known fact that noise exposure has a negative impact on the quality of hearing. In noise-exposed controls, hearing was clearly more impaired with increasing age and thus length of service than in teachers who were not continuously exposed to noise throughout their 8-hour working day. However, the assumption was not confirmed that teachers’ hearing would be also affected by school noise which is not negligible, as shown by several studies [13, 14, 15, 18]. The auditory threshold quality is positively influenced mainly by the teachers’ working time, with direct work with children accounting for only four to seven 45-minute lessons per day. After that time, most teachers seek silence and quiet that aid in hair cell regeneration [12]. Teachers’ hearing was only naturally impaired due to their increasing age, suggesting that teachers properly care for their hearing and try to avoid non-occupational exposure to excessive noise.

However, the limitation of the study is that noise in both schools and workplaces of the participants was not objectively measured.

CONCLUSION

The statistical analyses showed auditory threshold impairment (most notably at high frequencies) in nursery and primary school female teachers related to their length of service which was highly correlated with their age. The teachers’ audiograms were not suggestive of occupational noise exposure-related hearing loss but reflected age-related damage to the hearing apparatus. This fact was also confirmed by comparing their auditory thresholds with those in the control group comprising female respondents who had been exposed to high-risk levels of noise for most of their lives. The controls exposed to high-risk occupational noise levels had much worse auditory thresholds and this was true for not only high frequencies.

The original hypothesis that noise in the school setting may have a negative impact on teachers’ hearing was not confirmed. By contrast, the study results showed that teaching in nursery and primary schools was not associated with the quality of teachers’ auditory thresholds. Given the fact that few studies were concerned with noise exposure in schools, it would be reasonable to continue with the research and to focus also on the extra-auditory effect of noise on teachers, in particular the impact of noise on the cardiovascular system, including assessments of blood pressure, sleep disorders, fatigue, stress, problems with communicating, neurological difficulties, problems in mental functioning, etc.

The study was a part of Czech Ministry of Health grant agency project no. NT12246-5/2011 called An Epidemiological and Genetic Study of the Frequency of Hearing Impairment.

Do redakce došlo dne 5. 10. 2016.

Do tisku přijato dne 19. 10. 2016.

Adresa pro korespondenci:

Mgr. Petra Sachová, Ph.D.

Tománkova 100/49

683 01 Rousínov

e-mail: sachova.petra@gmail.com

Sources

1. Albera, R., Lacilla, M., Piumetto, E., Canale, A. Noise-induced hearing loss evolution: influence of age and exposure to noise. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol., 2010 May; 267, 5, s. 665–671.

2. Bencko, V. et al. Hygiena: učební texty k seminářům a praktickým cvičením. Praha: Karolinum 2000.

3. Clark, J. G. Uses and abuses of hearing loss classification. Asha, 1981, 23, 493–500.

4. Concha-Barrientos, M., Campbell-Lendrum, D., Steenland, K. Occupational noise: assessing the burden of disease from work-related hearing impairment at national and local levels. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004.

5. Deafness and hearing loss. World Health Organization. March 2015.

6. Dube, K. J., Ingale, L. T., Ingale, S. T. Hearing impairment among workers exposed to excessive levels of noise in ginning industries. Noise Health., 2011 Sep–Oct, 13, 54, s. 348–355.

7. Eysel-Gosepath, K., Daut, T., Pinger, A., Lehmacher, W., Erren, T. Effects of noise in primary schools on health facets in German teachers. Noise Health., 2012 May–Jun, 14, 58, s. 129–134.

8. Eysel-Gosepath, K., Pape, H. G., Erren, T., Thinschmidt, M., Lehmacher, W., Piekarski, C. Sound levels in nursery schools. HNO, 2010 Oct, 58, 10, s. 1013–1020.

9. Hahn, A. Otorinolaryngologie a foniatrie v současné praxi. Praha: Grada; 2007.

10. Helzner, E. P. et al. Race and Sex Differences in Aged-Related Hearing Loss The Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J. Am. Geriat. Soc., 2005, Volume 53, Issue 12.

11. Jelen, V. Statistická ročenka školství: Výkonové ukazatelé 2012/13. Ministerstvo školství mládeže a tělovýchovy. April 2013.

12. Kabátová, Z., Profant, M. Audiológia. Praha: Grada, 2012.

13. Koszarny, Z., Goryński, P. Exposure of schoolchildren and teachers to noise at school. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig., 1990, 41, 5–6), s. 297–310.

14. Koszarny, Z., Jankowska, D. Determination of the acoustic climate inside elementary schools. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig., 1995, 46, 3, s. 305–314.

15. Koszarny, Z., Jankowska, D. Noise in vocational schools. Causes of occurrence and assessment of exposure to schoolchildren. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig., 1994, 45, 3, s. 249–256.

16. Lejska, M. Základy praktické audiologie a audiometrie. Brno: Institut pro další vzdělávání pracovníků ve zdravotnictví, 1994, ISBN 80-701-3178-0.

17. Martins, R. H., Tavares, E. L., Lima Neto, A. C., Fioravanti, M. P. Occupational hearing loss in teachers: a probable diagnosis. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol., 2007, 73, 2, s. 239–244.

18. Mikulski, T., Sarosiek, F., Kolmer, R. Noise level in Szczecin schools and selected health indicators of students. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig., 1994, 45, 3, s. 257–262.

19. Mrázková, E., Mrázek, J., Lindovská, M. Základy audiologie a objektivní audiometrie. Medicínské a sociální aspekty sluchových vad. Ostrava: Repronis Ostrava, 2006, ISBN 80-7368-226-5.

20. Pray, W. S., Pray, J. J. Aged-related hearing loss in men. US Pharmacist, 2005.

21. Řezanka, M. Zaostřeno na ženy a muže 2012. Český statistický úřad, 2012.

Labels

Hygiene and epidemiology Hyperbaric medicine Occupational medicine

Article was published inOccupational Medicine

2016 Issue 4

Most read in this issue- Exogenous allergic alveolitis „hot tub lung“

- Occupational asthma – an occupational disease with uncertain prognosis

- Diagnosis: The orderly

- Tick-borne encephalitis as an occupational disease – case report

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career