-

Medical journals

- Career

Early vedolizumab trough levels are not associated with short-term response in patients with inflammatory bowel disease

Authors: Pudilova K. 1; Kolar M. 1; Ďuricová D. 1; Malickova K. 1,2; Hrubá V. 1; Machková N. 1; Vanickova R. 1; Mitrová K. 1; Lukas M. 1; Vasatko M. 1; Bortlík M. 1,3,4

Authors‘ workplace: The Clinical and Research Centre for Inflammatory Diseases ISCARE I. V. F. a. s., Prague, Czech Republic 1; Institute of Medical Biochemistry and Laboratory Diagnostics, General University Hospital and First Faculty of Medicine Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 2; Department of Internal Medicine, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and Military University Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic 3; Institute of Pharmacology, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 4

Published in: Gastroent Hepatol 2019; 73(1): 32-36

Category: IDB: Original Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amgh201932Overview

Background:

Data about the usefulness of monitoring vedolizumab therapy are sparse and conflicting. Here, the aim was to assess the association between early vedolizumab trough levels (VTLs) and responses to induction therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Methods:

The study population comprised consecutive IBD patients from a prospective cohort of vedolizumab treated individuals at our centre, in whom VTLs and anti-vedolizumab antibodies (AVAs) were measured during the induction phase of therapy. Included patients received vedolizumab (300 mg) at weeks 0, 2 and 6, with an extra dose at week 10 in cases of inadequate response after the third infusion. Clinical response was evaluated by a physician at 1 month after the last induction dose (week 10 or 14). Measurement of VTL and AVA was performed by ELISA.

Results:

Eighty-seven patients, 31 with Crohn’s disease and 56 with ulcerative colitis, were included. Only 15% of patients were naïve to anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy; 61% used concomitant systemic steroids and 26% used thiopurines. An additional dose at week 10 was given to 39% of individuals. Clinical response to induction was reported in 77% of IBD patients. The median VTL at week 6 was 30.6 µg/mL (range: 1.1–80.0). When comparing patients with and without a clinical response to vedolizumab, we found no significant difference in the median VTL at week 6 (29.4 vs. 34.4 µg/mL, respectively; p = 0.71). Likewise, VTL did not differ significantly between individuals receiving an additional dose at week 10 and those receiving standard induction (40.0 vs. 28.5, respectively; p = 0.69). Seven per cent of patients developed positive AVA up until weeks 10–14. Diagnosis type, concomitant immunosuppressants or previous biologic therapy had no impact on VTL.

Conclusion:

There was no association between early VTL and clinical response to induction therapy. Further studies should address the clinical relevance of therapeutic drug monitoring during long-term vedolizumab treatment.

Key words:

inflammatory bowel disease – vedolizumab – trough levels – clinical response

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) comprises ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn‘s disease (CD), which are characterised by idiopathic relapse-remitting inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. These chronic disorders can result in irreversible mucosal damage, disability, and increased incidence of colitis-associated neoplasia [1]. The mainstay of treatment for IBD is inducing and maintaining disease remission. New therapeutic goals also involve achieving mucosal healing, which has been shown to lead to improved clinical outcomes, including lower rates of surgical intervention [2].

Traditionally, the drugs used in the treatment of IBD are mesalazine derivatives, glucocorticoids and immunomodulators. With the advances in medical science and technology, a new group of drugs emerged, called the biologics. The most widely used biologics are the tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors such as infliximab and adalimumab, which are highly effective in the treatment of both UC and CD. The newer biologic agents in IBD include the integrin receptor antagonist vedolizumab and IL-12 and IL-23 antagonist, ustekinumab [3].

Despite these advances, a significant proportion of patients either fail to initially respond to biologics, or lose response with time. Therefore, there is an unmet need to optimise biologics in order to improve patient outcomes [4]. The role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) – measuring drug through levels and specific antidrug antibodies – in guiding therapeutic decisions in IBD patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors is now widely accepted since it has shown to deliver more clinically effective dosing [5,6]. TDM has now become the standard of care when prescribing anti-TNF-α therapy in patients with IBD, in particular for managing primary or secondary loss of response [4].

Vedolizumab is a humanised immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody that binds exclusively to the lymphocyte integrin α4 β7 and is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with moderately to severely active UC or CD. By binding specifically to α4 β7, vedolizumab inhibits the interaction of α4 β7 – expressing cells, in particular memory T lymphocytes, with mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) on endothelial cells, thereby blocking the infiltration of these cells into the gastrointestinal mucosa and gut-associated lymphoid tissue and suppressing gut inflammation [7– 9].

Published data regarding the role of TDM for IBD patients treated with vedolizumab are limited and it is still unknown whether TDM of vedolizumab could improve patient management [10]. The aim of our study was thus to assess the association between early vedolizumab through levels (VTL) and response to induction therapy in patients with IBD.

Methods

Patient population

Study population comprised consecutive IBD patients from a prospective cohort of vedolizumab-treated patients at our centre, who initiated vedolizumab therapy between 2/ 2017 and 8/ 2018. Eligible patients for the study have had VTL (vedolizumab trough levels) and anti-vedolizumab antibodies (AVA) measured during induction phase of therapy. All patients received vedolizumab 300 mg infusion at weeks 0, 2 and 6. In case of inadequate response after the 3rd infusion, an additional dose at week 10 was administered upon discretion of the treating physician.

Data collection

The data on patients’ demographics, disease characteristics and details on vedolizumab therapy were obtained primarily from the CREdIT registry which is a national database of IBD patients on biologic treatment. Data on biologic therapy, including dosage, treatment regime, adverse events and disease activity, are entered prospectively into the registry. Disease activity is determined by Harvey-Bradshaw index for CD and partial Mayo score for UC based on patients’ questionnaires that are filled out before each administration of biologic drug. Laboratory parameters such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and faecal calprotectin (FC) as well as missing information on clinical characteristics in the registry were obtained from patients’ medical records.

Clinical scores

Response to vedolizumab therapy was assessed one month after the last induction infusion (week 10 or week 14 in those receiving additional dose at week 10) and determined by physician global assessment (PGA). PGA was evaluated retrospectively using data from registry and medical records and defined as follows:

- a) complete response – complete improvement of clinical symptoms and laboratory markers (CRP < 5 mg/ L; FC < 150 µg/ g);

- b) partial response – improvement of clinical symptoms and/ or laboratory markers.

Patients who did not experience any improvement by the end of the induction phase were classified as primary non-responders.

Vedolizumab through levels and anti-vedolizumab antibodies measurement

At our centre, VTL and AVA are prospectively measured prior to each infusion starting at week 2 of induction phase of the treatment. VTL were quantified using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) following the manufacturer’s protocol (ImmunoGuide, Tani Medical). This ELISA is based on a vedolizumab-specific monoclonal antibody (catcher Ab, ImmunoGuide clone19F3). The level of detection of the assay was 1.9 µg/ mL and the measurement range of VTL was 0– 600 µg/ mL. AVA measurement was performed by a bridging type ELISA (ImmunoGuide, Tani Medical) for a semi-quantitative determination of free antibodies to vedolizumab in serum and plasma. Cut-off value for the AVA levels was set at 3AU (arbitrary units)/ mL, samples with an equal and higher AVA than the cut-off value were considered to be positive.

Statistical analysis

Standard descriptive statistical analyses were performed, including frequency distributions for categorical data and calculation of median and range for continuous variables. Difference between outcome variables (VTLs, CRP and FC) was analyzed using a Mann-Whitney test, not assuming normal distribution of the variables. A receiver operating characteristic analysis was performed for analysis of the discriminatory accuracy of vedolizumab levels for PGA response outcome. Multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression to evaluate predictive value of selected factors for PGA response. The statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.1) and IBM SPSS Statistics 24. A p-value (two-tailed) < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

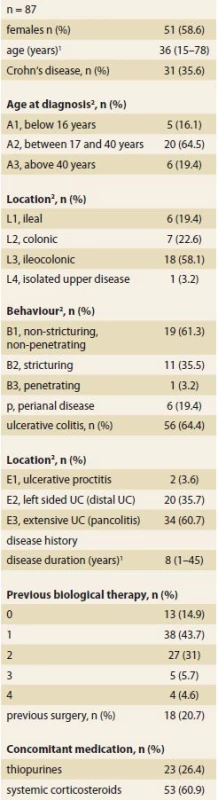

A total of 87 IBD patients were included, 31 with CD and 56 with UC. Most of the patients (74, 85.1%) were anti-TNF-α experienced, only a minority were naïve to biologic therapy (13, 14.9%). Concomitant use of thiopurines was present in 23 (26.4%) patients and 53 (60.9%) patients had systemic corticosteroids. Disease and baseline characteristics of included patients are shown in Tab. 1.

1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients at week 0.

Tab. 1 Demografické a klinické charakteristiky pacientů v týdnu 0.

1 median (range)

2 Montreal classifi cation

UC – ulcerative colitisMedian (range) CRP levels at the beginning of therapy (week 0) were 7.6 (0.3– 97.9) mg/ L in CD patients and 2.0 (0.2– 62.8) mg/ L in UC patients. Week 0 FC levels were 1 419 (55– 6 000) µg/ g in CD patients and 2 207 (34– 6 274) µg/ g in UC patients.

Treatment response

One third of patients (33, 38%) needed additional dose of vedolizumab at week 10 (9 patients with CD and 24 patients with UC). Data for evaluation of clinical response at week 10– 14 were available for 77 out of 87 IBD patients (88.5%). Of them, 59 (76.6%) patients were considered responders to induction therapy, 8 (10.4%) had complete and 51 (66.2%) partial response while 18 (23.4%) experienced primary non-response (Graph 1).

1. Response to vedolizumab therapy according to Physician Global Assessment at week 10-14. Graf 1. Odpověď na léčbu vedulizumabem hodnocená dle Physician Global Assessment v týdnu 10-14.

Vedolizumab Trough Levels and Antibodies

At week 6, median VTLs in the entire study population were 30.6 µg/ mL (1.1– 80.0) with no significant difference between CD and UC (27.8 vs 33.5 µg/ mL; p = 0.21).

Out of 85 patients with available AVA values, 6 (7.1%) developed positive AVA until week 10– 14.

Comparing patients with and without clinical response to vedolizumab induction therapy, no significant difference in median VTL was found (29.4 vs 34.4 µg/ mL; p = 0.71). A subgroup analysis of individuals with CD and UC separately revealed similar findings to the whole cohort (Graph 2a,b,c). Furthermore, week 6 VTLs of patients with additional dose at week 10 did not significantly differ from those obtaining standard induction only (40.0 vs. 28.5 µg/ mL; p = 0.69).

2. a,b,c. Vedolizumab trough levels at week 6 according to treatment response at week 10-14 in patients with – a. inflammatory bowel disease, b. Crohn‘s disease, c. ulcerative colitis.

Results are expressed as median (range).

Graf 2a,b,c. Hladiny vedolizumabu v týdnu 6 dle odpovědi na léčbu v týdnu 10-14 u pacientů s – a. idiopatickým střevním zánětem, b. Crohnovou nemocí, c. ulcerózní kolitidou.

Výsledky jsou uvedeny ve formátu medián (range).

Analysis of factors with potential impact on VTL revealed no significant association with age, gender, disease characteristics, previous anti-TNF-α therapy or use of concomitant immunosuppressive treatment (data not shown).

Discussion

In our observational study, we explored the association between early VTL and response to induction therapy in patients with IBD. Around three quarters of patients were considered responders to induction therapy. However, approximately one third of them required an additional dose at week 10. VTLs at week 6 were neither predictive of short-term response to vedolizumab nor of a need for treatment intensification during induction phase. Immunogenicity was slightly higher with AVA being detected in 7% of patients.

The rate of short-term response observed in our cohort is in agreement with findings of other observational studies despite different definitions used [11]. Slightly over one third of our patients needed an additional dose at week 10 of induction phase. Previous studies reported wide range of treatment intensification during induction phase, from 11% to 54% of treated patients, which may reflect different treatment policy of individual centres [10– 12].

We failed to demonstrate significant difference in early VTLs comparing patients with and without clinical response to vedolizumab induction therapy. In the literature, results on predictive value of early VTL on short-term but also long-term vedolizumab response are conflicting. While some studies suggested significant differences in VTL already at week 2 of vedolizumab therapy, others failed to prove any associations of VTL during induction phase with short - or long-term efficacy [7,10– 14].

Furthermore, no difference in VTL, stratified by need for additional dose at week 10, was found in our study. Similar results were reported in other observational cohort studies [10,11].

The role of TDM in optimising anti-TNFs agents to treat IBD has been long established, especially in situations of treatment failure [15]. For vedolizumab, however, the efficacy of TDM and its potential use for improving clinical outcomes is yet to be determined. It has been reported that serum concentrations of vedolizumab needed for complete receptor occupancy, either on circulating or mucosal T cells, do not correspond to that required for therapeutic efficacy [16]. Recent study from Israel showed that already low concentrations of vedolizumab led to full receptor saturation of peripheral blood T cells and that the rate of receptor occupancy on both peripheral and mucosal T cells was unrelated to treatment response [10]. So, as discussed by Ward et al., it is possible that unlike anti-TNFs, serum through levels alone may be inadequate to predict clinical response with vedolizumab. Therefore, new biomarkers which more accurately reflect the vedolizumab pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship are needed [4].

Seven percent of patients from our cohort developed positive AVA by week 10– 14. This is slightly higher than reported by studies using drug-sensitive assays with AVA rates of less than 5% [4]. Interestingly, data from Leuven (using drug tolerant assay) suggested that most of these early AVAs are only transient, have no impact on treatment response, and disappear during maintenance phase [17]. Similar observation was reported also in the study from Israel [10].

No significant association was found between VTL and diagnosis, sex, age, disease characteristics or use of immunomodulators or systemic corticosteroids. A recently published study by Al-Bawardy et al. supports our findings by having observed there was no significant difference in median VTLs between patients receiving and not receiving immunosuppressants (16.1 µg/ mL vs. 14.8 µg/ ; p = 0.81) or between those treated or not treated with corticosteroids (16.8 µg/ mL vs. 14.8 µg/ mL; p = 0.76) [18].

There are several limitations of our study. Firstly, our patient cohort was relatively small, especially regarding CD patients. Furthermore, some data were collected retrospectively, including assessment of disease activity by PGA. Finally, we did not evaluate objective parameters of treatment response such as biomarkers alone or mucosal healing.

In conclusion, our study did not find any association between early VTL and a short-term response to induction therapy in IBD patients. There is a need for further studies with larger patient populations to address the usefulness of TDM in short and long-term vedolizumab treatment.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE „uniform requirements“ for biomedical papers.

Funding

This study was supported by the IBD-COMFORT foundation.

Submitted: 28. 1. 2019

Accepted: 3. 2. 2019

MUC. Karolína Pudilová

The Clinical and Research Centre

for Inflammatory Diseases

ISCARE I.V.F. a.s.

Jankovcova 1569/ 2c

170 00 Prague

Czech Republic

Sources

1. Nemati S, Teimourian S. An overview of inflammatory bowel disease: general consideration and genetic screening approach in diagnosis of early onset subsets. Middle East J Dig Dis 2017; 9(2): 69– 80. doi: 10.15171/ mejdd.2017.54.

2. Chan HC, Ng SC. Emerging biologics in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol 2017; 52(2): 141– 150. doi: 10.1007/ s00535-016-1283-0.

3. Rawla P, Sunkara T, Raj JP. Role of biologics and biosimilars in inflammatory bowel disease: current trends and future perspectives. J Inflamm Res 2018; 11 : 215– 226. doi: 10.2147/ JIR.S165330.

4. Ward MG, Sparrow MP, Roblin X. Therapeutic drug monitoring of vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease: current data and future directions. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2018; 11 : 1756284818772786. doi: 10.1177/ 1756284818772786.

5. Yacoub W, Williet N, Pouillon L et al. Early vedolizumab trough levels predict mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: a multicentre prospective observational study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 47(7): 906– 912. doi: 10.1111/ apt.14548.

6. Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, Kupfer SS et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2017; 153(3): 827– 834. doi: 10.1053/ j.gastro.2017.07.032.

7. Rosario M, French JL, Dirks NL et al. Exposure-efficacy relationships for vedolizumab induction therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn‘s disease. J Crohns Colitis 2017; 11(8): 921– 929. doi: 10.1093/ ecco-jcc/ jjx021.

8. Loftus EV Jr, Colombel JF, Feagan BG et al. Long-term efficacy of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2017; 11(4): 400– 411. doi: 10.1093/ ecco-jcc/ jjw177.

9. Vermeire S, Colombel JF, Feagan BG et al. Long-term efficacy of vedolizumab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohn Colitis 2017; 11(4): 412– 424. doi: 10.1093/ ecco-jcc/ jjw176.

10. Ungar B, Kopylov U, Yavzori M et al. Association of vedolizumab level, anti-drug antibodies, and α4β7 occupancy with response in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 16(5): 697– 705.e7. doi: 10.1016/ j.cgh.2017.11.050.

11. Dreesen E, Verstockt B, Bian S et al. Evidence to support monitoring of vedolizumab trough concentrations in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 16(12): 1937– 1946.e8. doi: 10.1016/ j.cgh.2018.04.040.

12. Williet N, Boschetti G, Fovet M et al. Association between low trough levels of vedolizumab during induction therapy for inflammatory bowel diseases and need for additional doses within 6 months. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15(11): 1750– 1757.e3. doi: 10.1016/ j.cgh.2016.11.023.

13. Schulze H, Esters P, Hartmann F et al. A prospective cohort study to assess the relevance of vedolizumab drug level monitoring in IBD patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 2018; 53(6): 670– 676. doi: 10.1080/ 00365521.2018.1452974.

14. Yarur A, Bruss A, Fox C et al. DOP048 Vedolizumab levels during induction are associated with long-term clinical and endoscopic remission in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2018; 12 (Suppl 1): S064– S065. doi: 10.1093/ ecco-jcc/ jjx180.085.

15. Mitrev N, Vande Casteele N, Seow CH et al. Review article: consensus statements on therapeutic drug monitoring of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 46(11– 12): 1037– 1053. doi: 10.1111/ apt.14368.

16. Rosario M, Dirks NL, Milch C et al. A review of the clinical pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and immunogenicity of vedolizumab. Clin Pharmacokinet 2017; 56(11): 1287– 1301. doi: 10.1007/ s40262-017-0546-0.

17. Bian S, Dreesen E, Tang HT et al. Antibodies toward vedolizumab appear from the first infusion onward and disappear over time. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017; 23(12): 2202– 2208. doi: 10.1097/ MIB.0000000000001255.

18. Al-Bawardy B, Ramos GP, Willrich MAV et al. vedolizumab drug level correlation with clinical remission, biomarker normalization, and mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018. doi: 10.1093/ ibd/ izy272.

Labels

Paediatric gastroenterology Gastroenterology and hepatology Surgery

Article was published inGastroenterology and Hepatology

2019 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- News in 2019

- Biologics for inflammatory bowel disease – forth time

- Inflammatory bowel disease and medical assessment service

- Treatment of a pregnant Crohn’s disease patient with ustekinumab: a case report

- Surprising etiology of terminal common bile duct stricture

- Therapeutic trial of proton pump inhibitors for management of patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux

- Does abdominal compression improve the success rate of and tolerance to colonoscopy?

- Toxic and drug damage of the liver and kidneys

- The selection from international journals

- Clensia® – the first combined cleansing agent with simeticone

- Vedolizumab vs. ustekinumab as second-line therapy in Crohn’s disease in clinical practice

- Early vedolizumab trough levels are not associated with short-term response in patients with inflammatory bowel disease

- Ileocaecal Crohn’s disease and familial adenomatous polyposis in one patient – a case report

- First European Conference of Young Gastroenterologists – ECYG

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Clensia® – the first combined cleansing agent with simeticone

- Toxic and drug damage of the liver and kidneys

- Surprising etiology of terminal common bile duct stricture

- Therapeutic trial of proton pump inhibitors for management of patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career