Fumarate hydratase deficient renal cell carcinoma and fumarate hydratase deficient-like renal cell carcinoma: Morphologic comparative study of 23 genetically tested cases

Authors:

Kristýna Pivovarčíková 1; Petr Martínek 1; Kiril Trpkov 2; Reza Alaghehbandan 3; Cristina Magi-Galluzzi 4; Enric Condom Mundo 5; Daniel Berney 6; Saul Suster 7; Anthony Gill 8; Boris Rychlý 9; Květoslava Michalová 1; Tomáš Pitra 10; Milan Hora 10; Michal Michal 1; Ondřej Hes 1

Authors‘ workplace:

Department of Pathology, Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Medicine in Plzeň, Pilsen, Czech Republic

1; Calgary Laboratory Services and University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

2; Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Royal Columbian Hospital, Vancouver, BC, Canada

3; Robert J. Tomsich Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA

4; Department of Pathology, Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL), Barcelona, Spain

5; Bart’s Cancer Center, London, United Kingdom

6; Department of Pathology, Medical College Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA

7; Royal North Shore Hospital, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

8; Department of Pathology, Cytopathos, Bratislava, Slovakia

9; Department of Urology, Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Medicine in Plzeň, Pilsen, Czech Republic

10

Published in:

Čes.-slov. Patol., 55, 2019, No. 4, p. 244-249

Category:

Overview

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma-associated renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC)/ fumarate hydratase deficient renal cell carcinoma (FHRCC) is an aggressive tumor defined by molecular genetic changes - alteration in fumarate hydratase (FH) gene. The morphologic spectrum of HLRCC/FHDRCC is remarkably variable. The presence of large nuclei and prominent dark red inclusion-like nucleoli and perinucleolar clearing are considered as helpful morphologic clue. We selected 23 renal neoplasms primarily based on their morphologic features suspicious for HLRCC/FHDRCC. Morphological, basic immunohistochemical, and genetic analysis was performed. The tumors were divided in two groups according to the molecular genetic findings. The first group included 13 tumors with detected FH mutation/LOH (compatible with diagnosis FHRCC), and the second group included 10 tumors without FH mutation/LOH (FH-like RCCs). In the FHRCC group, the vast majority of cases (9/13) had mixed morphology with different architectural growth patterns. All cases showed prominent macronucleoli, and perinucleolar clearing was found in 10/13 cases. Immunohistochemically, 6/7 FHRCC cases were negative for FH antibody, while one case showed strong diffuse FH reactivity. The FH-like RCC group showed more uniform architectural growth pattern. All 10 tumors had prominent macronucleoli, and perinucleolar clearing was present in 8/10 cases. Eight FH-like RCC cases showed diffuse strong positivity for FH, although 2 cases were completely negative for FH. It is evident that neither morphologic feature nor immunohistochemical analysis can be reliably used in routine practice for the diagnosis of HLRCC/FHRCC. In suspected cases, the diagnosis of HLRCC/FHRCC can be confirmed by molecular-genetic testing for FH mutation. It should be noted that the traditionally described morphologic features of HLRCC/FHRCC (prominent eosinophilic macronuclei with perinucleolar halos) can frequently be seen in other renal neoplasms.

Keywords:

fumarate hydratase – HLRCC – Renal cell carcinoma

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma-associated renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) is an aggressive tumor defined by molecular genetic changes, namely mutation in fumarate hydratase (FH) gene. It has been recently proposed that renal tumors associated with impaired FH gene to be named fumarate hydratase deficient renal cell carcinoma (FHRCC). The term HLRCC is used for patients with germline mutation of FH gene, autosomal dominant heredity and syndromic presentation with concurrent presence of cutaneous and/or uterine leiomyomas (1, 2). On the other hand, the term FHRCC is recommended for tumors with suggestive morphology and typical immunophenotype in the setting of uncertain clinical and family history and unknown genetic status. FHRCC also allows designation of cases that might represent apparently sporadic forms, harboring somatic (not germline) alterations in the FH gene (3-5). Overall, HLRCC/FHRCC is a distinct histomolecular entity.

The morphologic spectrum of HLRCC/FHRCC is remarkably variable, with various architectural and histologic features being reported in the literature (4-19). Immunohistochemical examination can be helpful in the diagnosis of these tumors with combined negative staining for fumarate hydratase (FH) and strong positive staining for 2-succinocysteine (2SC), demonstrating good sensitivity and excellent specificity (4, 20). Nonetheless, molecular genetic testing for FH mutation/LOH still remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of HLRCC/FHRCC.

While HLRCC/FHRCC is one of the most challenging renal tumors in routine practice, its detection can have a significant impact on family members and potentially the patient. Thus, pathologists should be aware of this entity, given its highly variable morphology and difficult immunohistochemical evaluation, to be able to identify suspect cases to be genetically tested.

In this study, we compared morphologic, immunohistochemical and molecular-genetic features between FHRCC (confirmed cases) and FH-like RCC tumors (suspicious cases).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Case identification

Twenty three tumors suspect for FHRCC primarily based on morphology were identified in the Plzen Tumor Registry out of 26,000 renal neoplasms. Nine cases in this study were previously published (4), and 13 cases were included which were previously published by our group (21). All cases were reviewed by two Urologic Pathologists (KP and OH). Tissues for light microscopy were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin using routine procedure. Sections 4 µm thick were cut from tissue blocks and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). There were 1 to 48 tissue blocks (median 1) for each case. However all original HE slides were reviewed and evaluated. One representative block was selected for immunohistochemical and molecular–genetic studies (usually block with internal positive control of non-neoplastic renal parenchyma).

Tumors were divided in two groups after molecular genetic analysis. The first group included 13 tumors with detected FH mutation/LOH (compatible with diagnosis FHRCC), and the second group included 10 tumors without FH mutation/LOH (these cases are hereafter referred as FH-like RCC).

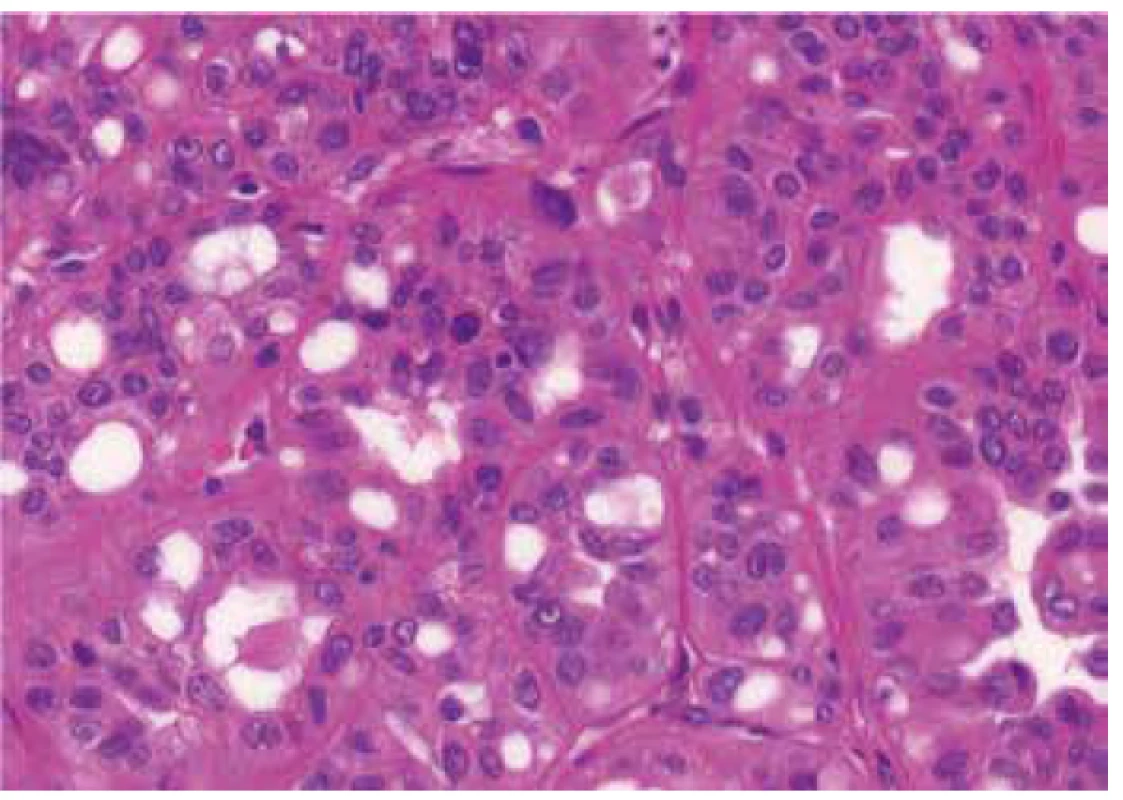

Architectural patterns, and morphologic features including the presence of prominent macronucleoli and perinucleolar clearing were analyzed in all 23 tumors. Macronucleoli were described as a prominent dark red inclusion-like nucleoli, and a perinucleolar clearing was defined as an clear area between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (as seen by light microscopy at high magnification). Different growing patterns were detected in the tumors (papillary, tubulary, solid, cribriform, sarcomatoid, multicystic), every architectural pattern representing more than 5% of the whole tumor mass were count into definitive architectural results.

Immunohistochemistry

The immunohistochemical analysis was performed using a VentanaBenchMark ULTRA (Ventana Medical System, Inc., Tucson, Arizona), FH antibody (J-13, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, dilution 1:3000) was used. Appropriate positive controls were included.

Molecular genetic testing

All cases demonstrating suspicious morphology for FHRCC underwent molecular evaluation for FH gene mutation status by Sanger sequencing and loss of heterozygosity studies on DNA extracted from macrodissected FFPE tissue. We also evaluated 10 cases with retained FH expression for FH mutation, as a negative control group. Previously described custom primer sets were used for Sanger sequencing, and the whole coding sequence including exon-intron junctions was sequenced using primers designed to produce short amplicons suitable for degraded formalin fixed DNA(22). Loss of heterozygosity studies were performed using a previously described set of 6 polymorphic short tandem repeat markers (D1S517, D1S2785, D1S180, AFM214xe11, D1S547, and D1S2842), surrounding the FH gene (22).

RESULTS

Fumarate hydratase renal cell carcinoma group (FH RCC group)

FHRCC cohort included 13 tumors from 12 patients. Patients were 8 males and 4 females, with age range of 24-65 years (mean 50.8 years). Tumor size ranged from 0.9-18 cm (mean 9.6 cm).

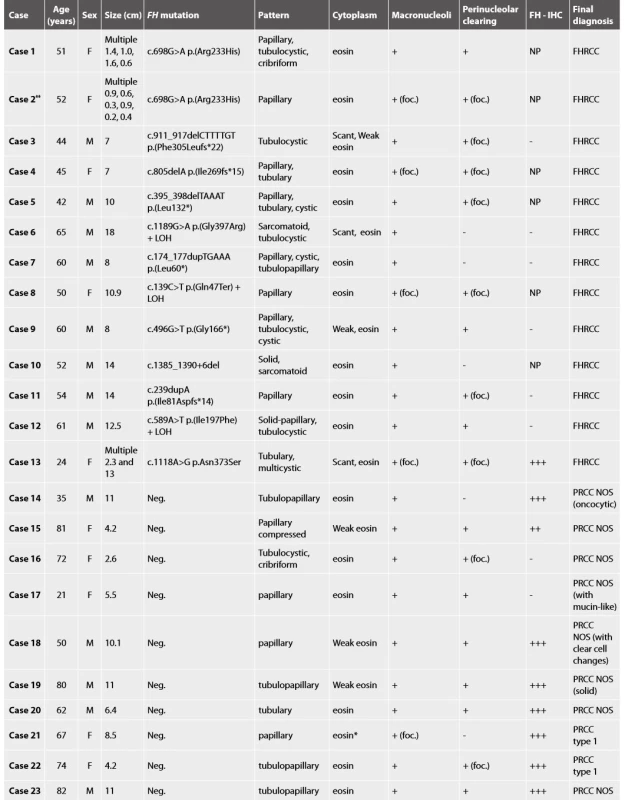

Molecular genetic analysis confirmed the presence of FH mutation/LOH in all 13 cases (Table 1).

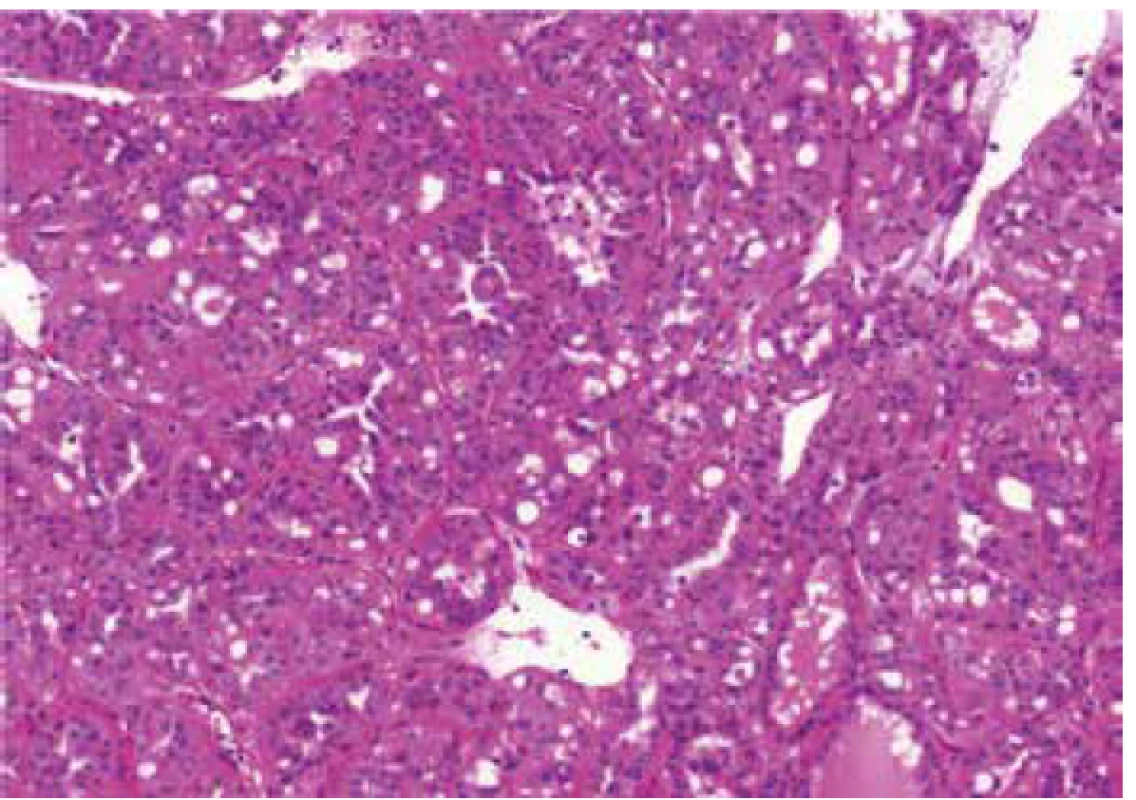

Histologic assessment showed mixed patterns in majority of cases (9/13 cases). Pure papillary architecture was detected only in 3/13 cases. Sarcomatoid differentiation was identified in 2/13 tumors. Cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells were bright eosinophilic in 9/13 cases, and weak to scant eosinophilic in four cases. All 13 tumors had prominent macronucleoli (focally in 4 tumors). Perinucleolar clearing was found in 10/13 (focally in 7 tumors).

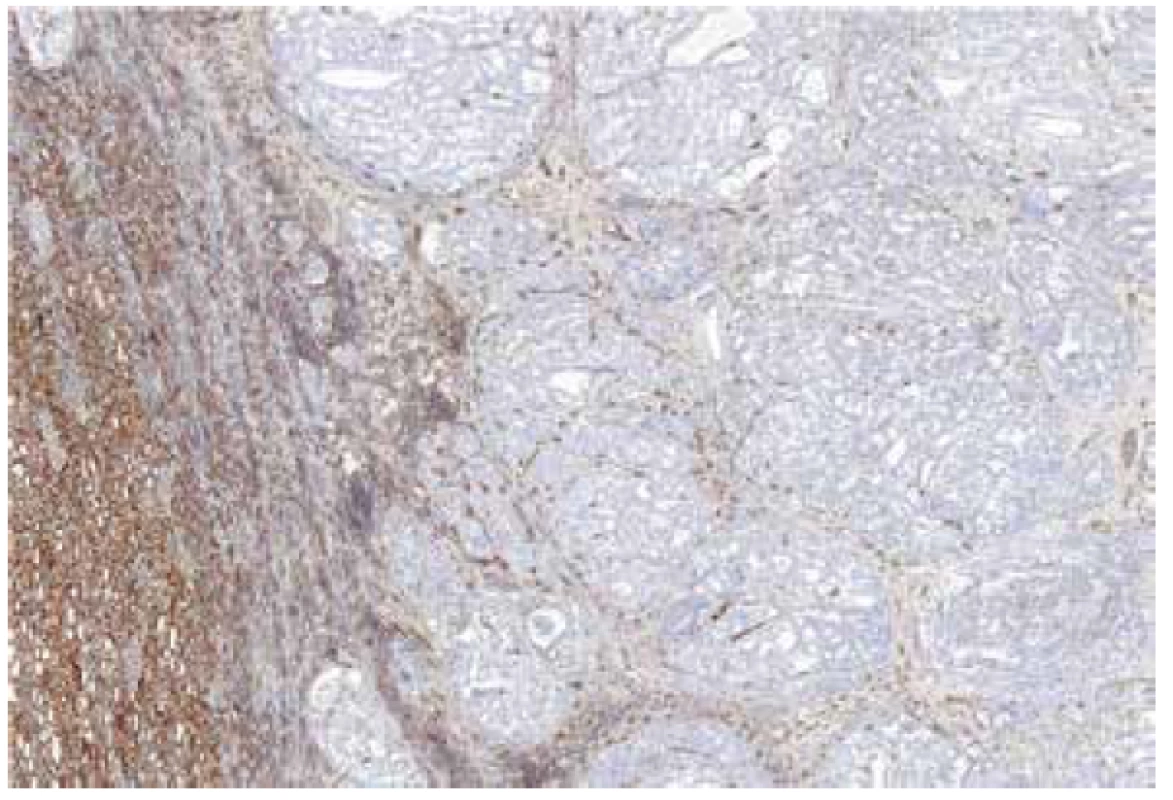

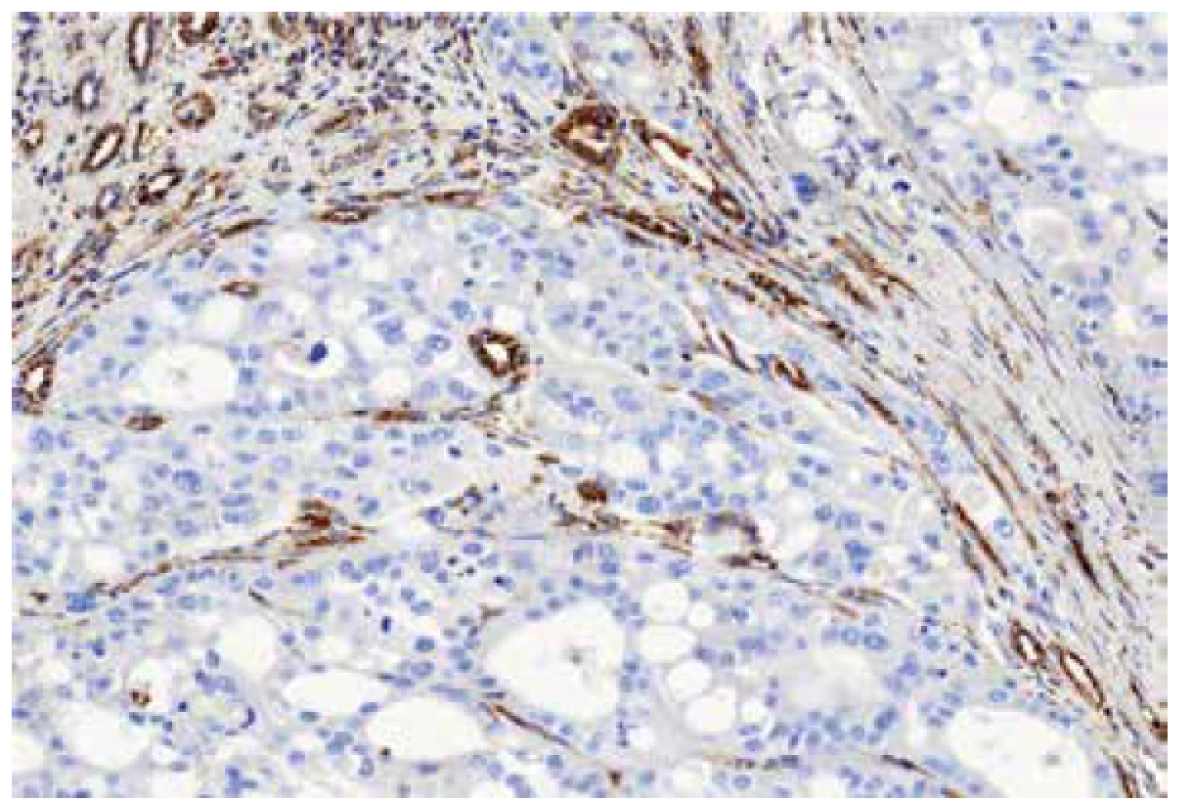

Material for seven tumors was available for immunohistochemical examination with FH antibody (7/13). Negative staining for FH was found in six cases (with presence of an appropriate positive internal control in adjacent non-neoplastic renal parenchyma), while one case showed strong diffuse FH reactivity (this case demonstrated genetically FH mutation c.1118A>G p.Asn373Ser).

Fumarate hydratase-like renal cell carcinoma group (FH-like RCC group)

Five males and five females with age range of 21-82 years (mean 62.4 years) were included in this group. Tumor size ranged from 2.6-11 cm (mean 7.5 cm).

No mutations/LOH of FH gene was identified in these 10 cases.

All 10 cases were considered suspicious for FHRCC based on morphology. These tumors were purely papillary in 4 cases, tubulopapillary in 4 cases, tubular in one case, and combined tubulo-cystic and cribriform in one case. Cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells was bright eosinophilic in 8/10 cases, while only focally in two cases. All 10 tumors had prominent macronucleoli (in one case only focally), and perinucleolar clearing was present in 8/10 cases (in 2 cases focally).

Immunohistochemistry showed diffuse strong positivity for FH in 8 cases, which was confirmed by the absence of FH mutations. Although 2 cases were completely negative for FH by immunohistochemistry (with an appropriate positive internal control), we were unable to demonstrate FH mutations in these cases.

Finally, all these 10 cases were classified as papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC), according to the current WHO classification (2). Two cases fulfilled the criteria for diagnosis PRCC type 1, and 8 tumors were classified as PRCC not otherwise specified (NOS).

DISCUSSION

In early publications, even in WHO 2004, the HLRCC/FHRCC was described as displaying typically PRCC type 2 histology (6,9). In recent years, the morphologic spectrum of HLRCC/FHRCC has expanded. It is now evident that the histologic appearance of this tumor is nearly unpredictable. HLRCC/FHRCC includes tumors with predominantly papillary or tubulocystic architecture, usually mixed with other growing patterns (cystic, tubulary, tubulopapillary, tubulocystic, solid). Sometimes, these tumors can closely mimic other renal neoplastic entities – e.g. collecting duct carcinoma, clear cell RCC, tubulocystic RCC, unclassified oncocytic tumor, or even oncocytic type of RCC resembling SDH-deficient RCC (4,5,7,8,10-13,15-19).

Historically, the presence of large nuclei, prominent dark red inclusion-like nucleoli and perinucleolar clearing were considered as helpful morphologic clue (11). However, it is now recognized that even these morphologic features are not consistently present. Recent study by Muller´s group clearly showed that these histologic features are not distinctive for HLRCC/FHRCC. They compared pathological features and imunohistochemical profile (FH/2SC immunohistochemistry) of 24 renal cell carcinomas from proven FH mutations carriers and 12 PRCC type 2 from patients without FH mutations. In this study, they reported the presence of prominent eosinophilic macronuclei with perinucleolar clearing in 58% PRCC type 2 from patients with no FH germline mutation. Further, they concluded that multiplicity of architectural patterns, rhabdoid/sarcomatoid components and combined FH/2SC staining can differentiate HLRCC from type 2 PRCC with efficient FH gene (20).

We investigated 23 renal tumors with suspicious histology for HLRCC/FHRCC. The vast majority of these cases were send to us by experienced uropathologists, either for a second opinion or for a molecular-genetic study. The histology was indeed suggestive of FHRCC in all cases, with predominantly papillary growth, often mixed with other patterns, prominent macronuclei (23/23), and perinucleolar clearing (18/23). The FH mutation/LOH was confirmed genetically in 13 cases. Four of the 13 genetically proven FHRCC in our cohort showed uniform architecture (3 with papillary and one with tubulocystic pattern), while 9 FHRCCs demonstrated mixed architectural patterns. On the other hand, the tumors that resembled FHRCC (FH-like RCC) were more architecturally uniform. Only one FH-like RCC had mixed growth pattern. Our study along with Muller’s study clearly showed that the multiplicity of architectural patterns in conjunction with pertinent immunohistochemical profile may help differentiate HLRCC/FHRCC from PRCC. It should be noted that prominent macronucleoli and perinucleolar clearing are not very specific for this type of neoplasia, and as such it should not be used as a determining criteria for the diagnosis of HLRCC/FHRCC.

Immunohistochemistry can be a useful diagnostic tool in these tumors. Concurrent negative staining for FH and positive staining for 2SC should demonstrate a very good sensitivity and specificity for detecting HLRCC/FHRCC (4). Unfortunately, 2SC immunohistochemistry is still not commercially available. In this study, we found that separate immunohistochemistry for FH, although useful as a screening test, is not 100% sensitive and specific. We identified 2 cases which showed negative FH reactivity by immunohistochemistry, in which we could not confirm a mutation/LOH of the FH gene by molecular-genetic tests (FH-like RCCs). Concurrently, immunohistochemical staining with FH antibody reached the sensitivity of 86% in our FHRCC/HLRCC cases. Other recently published study determined that single use of FH antibody shows specificity of 100% but sensitivity of 87.5% (20). This illustrates the limitations of the immunohistochemistry screening for FH in suspicious cases with overlapping histomorphologic patterns. In our view, all morphologically suspicious cases should be evaluated for FH gene mutations to separate the true HLRCC/FHRCC from their mimickers, regardless of the FH immunohistochemistry findings.

It is evident that neither morphologic feature nor immunohistochemical analysis can solely be used in routine practice for the diagnosis of HLRCC/FHRCC. Yet morphology and immunohistochemistry could aid and be used as a further screening tool in detecting suspicious cases for genetic testing.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings showed that it was virtually impossible to separate genuine HLRCC/FHRCC from cases that demonstrate morphologic similarities (FH-like RCC) solely based on morphologic features. Considering the limitations of immunohistochemistry, analysis of FH gene is currently the only reliable method for distinguishing HLRCC/FHRCC from their mimickers. Traditionally described histologic features of HLRCC/FHRCC (prominent eosinophilic macronuclei with perinucleolar halos) are frequently found in other renal neoplasms.

FUNDING

The study was supported by the Charles University Research Fund (project number Q39) and by Institutional Research Fund FN 00669806.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Kristýna Pivovarčíková, MD, PhD

Department of Pathology

Medical Faculty and Charles University Hospital Plzen

Alej Svobody 80, 304 60 Pilsen

Czech Republic

e-mail: pivovarcikovak@fnplzen.cz

Sources

1. Srigley JR, Delahunt B, Eble JN, Egevad L, Epstein JI, Grignon D, et al. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Vancouver Classification of Renal Neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37(10): 1469-1489.

2. Moch H, Humphrey PA, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Lyon: IARC; 2016.

3. Smith S, Trpkov K, Mehra R, Divatia M, Hes O, Menon S, et al. Is Tubulocystic Carcinoma With Dedifferentiation a form of HLRCC/Fumarate Hydratase-Deficient RCC? United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology (USCAP) - 104th Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, March 21-27, 2015. Mod Pathol 2015; 95 (Suppl 1): 260A.

4. Trpkov K, Hes O, Agaimy A, Bonert M, Martinek P, Magi-Galluzzi C, et al. Fumarate Hydratase-deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma Is Strongly Correlated With Fumarate Hydratase Mutation and Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 2016; 40(7): 865-875.

5. Smith SC, Trpkov K, Chen YB, Mehra R, Sirohi D, Ohe C, et al. Tubulocystic Carcinoma of the Kidney With Poorly Differentiated Foci: A Frequent Morphologic Pattern of Fumarate Hydratase-deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2016; 40(11): 1457-1472.

6. Launonen V, Vierimaa O, Kiuru M, Isola J, Roth S, Pukkala E, et al. Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001; 98(6): 3387-3392.

7. Alam NA, Rowan AJ, Wortham NC, Pollard PJ, Mitchell M, Tyrer JP, et al. Genetic and functional analyses of FH mutations in multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis, hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cancer, and fumarate hydratase deficiency. Hum Mol Genet 2003; 12(11): 1241-1252.

8. Toro JR, Nickerson ML, Wei MH, Warren MB, Glenn GM, Turner ML, et al. Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 73(1): 95-106.

9. Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours Pathology and Genetics Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. IARC Press Lyon. 2004.

10. Wei MH, Toure O, Glenn GM, Pithukpakorn M, Neckers L, Stolle C, et al. Novel mutations in FH and expansion of the spectrum of phenotypes expressed in families with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. J Med Genet 2006; 43(1): 18-27.

11. Merino MJ, Torres-Cabala C, Pinto P, Linehan WM. The morphologic spectrum of kidney tumors in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 2007; 31(10): 1578-1585.

12. Grubb RL, 3rd, Franks ME, Toro J, Middelton L, Choyke L, Fowler S, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: a syndrome associated with an aggressive form of inherited renal cancer. J Urol 2007; 177(6): 2074-2080.

13. Lehtonen HJ, Blanco I, Piulats JM, Herva R, Launonen V, Aaltonen LA. Conventional renal cancer in a patient with fumarate hydratase mutation. Hum Pathol 2007; 38(5): 793-796.

14. Koski TA, Lehtonen HJ, Jee KJ, Ninomiya S, Joosse SA, Vahteristo P, et al. Array comparative genomic hybridization identifies a distinct DNA copy number profile in renal cell cancer associated with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2009; 48(7): 544-551.

15. Harris M, Wallace J, Winship I, Hale L, Gardner M. Hereditary renal cell carcinoma: the clue can be in the skin. Intern Med J 2009; 39(12): e12-13.

16. Chen YB, Brannon AR, Toubaji A, Dudas ME, Won HH, Al-Ahmadie HA, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome-associated renal cancer: recognition of the syndrome by pathologic features and the utility of detecting aberrant succination by immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol 2014; 38(5): 627-637.

17. Smith SC, Sirohi D, Ohe C, McHugh JB, Hornick JL, Kalariya J, et al. A distinctive, low-grade oncocytic fumarate hydratase-deficient renal cell carcinoma, morphologically reminiscent of succinate dehydrogenase-deficient renal cell carcinoma. Histopathology 2017; 71(1): 42-52.

18. Vocke CD, Ricketts CJ, Merino MJ, Srinivasan R, Metwalli AR, Middelton LA, et al. Comprehensive genomic and phenotypic characterization of germline FH deletion in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2017; 56(6): 484-492.

19. Li Y, Reuter VE, Matoso A, Netto GJ, Epstein JI, Argani P. Re-evaluation of 33 ‘unclassified’ eosinophilic renal cell carcinomas in young patients. Histopathology 2018; 72(4): 588-600.

20. Muller M, Guillaud-Bataille M, Salleron J, Genestie C, Deveaux S, Slama A, et al. Pattern multiplicity and fumarate hydratase (FH)/S-(2-succino)-cysteine (2SC) staining but not eosinophilic nucleoli with perinucleolar halos differentiate hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma-associated renal cell carcinomas from kidney tumors without FH gene alteration. Mod Pathol 2018; 31(6): 974-983.

21. Alaghehbandan R, Stehlik J, Trpkov K, Magi-Galluzzi C, Condom Mundo E, Pane Foix M, et al. Programmed death-1 (PD-1) receptor/PD-1 ligand (PD-L1) expression in fumarate hydratase-deficient renal cell carcinoma. Ann Diagn Pathol 2017; 29: 17-22.

22. Martinek P, Grossmann P, Hes O, Bouda J, Eret V, Frizzell N, et al. Genetic testing of leiomyoma tissue in women younger than 30 years old might provide an effective screening approach for the hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome (HLRCC). Virchows Arch 2015; 467(2): 185-191.

Labels

Anatomical pathology Forensic medical examiner ToxicologyArticle was published in

Czecho-Slovak Pathology

2019 Issue 4

Most read in this issue

- Clinical perspective on the myocarditis and cardiomyopathies

- Fumarate hydratase deficient renal cell carcinoma and fumarate hydratase deficient-like renal cell carcinoma: Morphologic comparative study of 23 genetically tested cases

- A practical approach to the examination of the congenitally malformed heart at autopsy

- Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the uterus – case report