-

Medical journals

- Career

Dedifferentiated carcinoma of the ovary. A case report

Authors: Kristýna Němejcová 1; Jana Rosmusová 1; Michaela Bártů 1; Radoslav Matěj 1,2; Pavel Dundr 1

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Pathology, First Faculty of Medicine Charles University and General Teaching Hospital in Prague, Czech Republic 1; Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, Thomayer Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic 2

Published in: Čes.-slov. Patol., 54, 2018, No. 1, p. 33-36

Category: Original Article

Overview

We report the case of a 54-year-old female with dedifferentiated carcinoma of the ovary. Grossly, both ovaries were affected by a tumor of up to 25 mm (right ovary) and 220 mm (left ovary) in diameter. Microscopically, the tumors of both ovaries showed features of well differentiated endometrioid carcinoma with mucinous differentiation. Moreover, in the left ovary there was an undifferentiated solid component consisting of larger cells. Immunohistochemically, the undifferentiated component showed diffuse vimentin positivity and focal expression of cytokeratin 18. Other markers examined including PAX8, estrogen receptors and progesterone receptors were all negative. Dedifferentiated carcinomas consist of an undifferentiated epithelial component and a component of endometrioid carcinoma of FIGO grade 1 or 2. Clinically, they represent aggressive tumors with unfavorable prognosis mostly occurring in the endometrium. To the best of our knowledge, thus far only 6 cases arising in the ovary have been reported in the literature.

Keywords:

ovarian carcinoma – dedifferentiated carcinoma – undifferentiated carcinoma – low-grade endometrioid carcinoma

Dedifferentiated and undifferentiated carcinomas of the female genital tract are rare, clinically aggressive tumors, mostly arising in the endometrium (1,2). While undifferentiated carcinomas are malignant epithelial tumors without any differentiation, dedifferentiated carcinomas also contain, apart from the undifferentiated component, a second component of endometrioid carcinoma of FIGO grade 1 or 2. This association was first reported in endometrial tumors, and later on the dedifferentiated/undifferentiated carcinoma was also described in the ovary (3). Similar to the endometrial tumors, this type of carcinoma is associated with an unfavorable prognosis. To the best of our knowledge, only 6 cases of dedifferentiated carcinoma of the ovary have been described in literature to date (3-5).

Case Report

Clinical history

A 54-year-old woman with lower extremity pain was referred by a local physician for a complex examination, including an abdominal ultrasound which revealed some “suspect findings”. During the following check-up, a bilateral ovarian tumor was detected and the patient was referred to the oncogynecological center where she underwent a hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy. Subsequently, she received six cycles of adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy. She was also genetically tested for hereditary mutations in 13 genes including BRCA1and BRCA2, via the NGS and MLPA method, but no significant variants in coding sequence were found. Currently, 9 months after the surgery, the patient is under regular follow-ups with no signs of the disease.

Materials and Methods

Sections from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Selected sections were analyzed immunohistochemically using the avidin-biotin complex method with antibodies directed against the following antigens: cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (1 : 50, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), cytokeratin 18 (clone DC 10, dilution 1 : 50, Dako), cytokeratin 7 (clone OV-TL 12/30, 1 : 50, Dako), Ki-67 (clone MIB-1, 1 : 50, Dako), estrogen receptors (ER, clone 6F11, 1 : 50, Novocastra, Newcastle, UK), progesterone receptors (PR, clone 16, 1 : 200, Novocastra), p53 (clone BP 53-12, 1 : 200, Zytomed Systems, Berlin, Germany), synaptophysin (clone DAK-SYNAP, 1 : 50, Dako), chromogranin A (clone LK2H10, 1 : 400, Zytomed), S-100 protein (1 : 1600, Dako), HNF-1 β (polyclonal, dilution 1 : 500, Sigma-Aldrich, Prestige antibodies, St. Louis, United States), desmin (clone D33, 1 : 200, Dako), actin (clone HHF35, 1 : 400, Dako), Ber EP4 (clone Ber-EP4, 1 : 50, Dako), CD45/LCA (clone 2B11+PD7/26, 1 : 100, Dako), EMA (clone E29, 1 : 100, Dako), vimentin (clone V9, 1 : 50, Dako), PAX 8 (1 : 50, Cell Marque, Rocklin, California), Oct-4 (MRQ-10, 1 : 100, Cell Marque), SALL 4 (6E3, 1 : 100, Cell Marque), MLH-1 (clone G168-15, 1 : 50; Zytomed Systems), MSH-2 (clone FE 11, 1 : 50, Zytomed Systems), MSH-6 (clone FE 11, 1 : 50; Zytomed Systems), and PMS-2 (clone EPR3947, ready-to-use; Zytomed Systems), INI-1 (clone MRQ-27, 1 : 50, Cell Marque), Brg-1 (clone G-7, 1 : 25, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), and WT-1 (clone 6F-H2, 1 : 50, Dako)

Results

Grossly a bilateral adnexal involvement was apparent. The right ovary measured 50 x 30 x 20 mm and consisted of solid tumorous masses of up to 25 mm in diameter, with some visible cysts. The left ovary measured 220 x 140 x 120 mm and was multicystic in appearance, with some cauliflower-like masses on the external surface, measuring up to 60 mm. Both fallopian tubes seemed to be normal. The uterus was of normal size, with only a few small leiomyomas in the myometrium and an unsuspicious endometrial polyp the largest dimension of which being 25 mm.

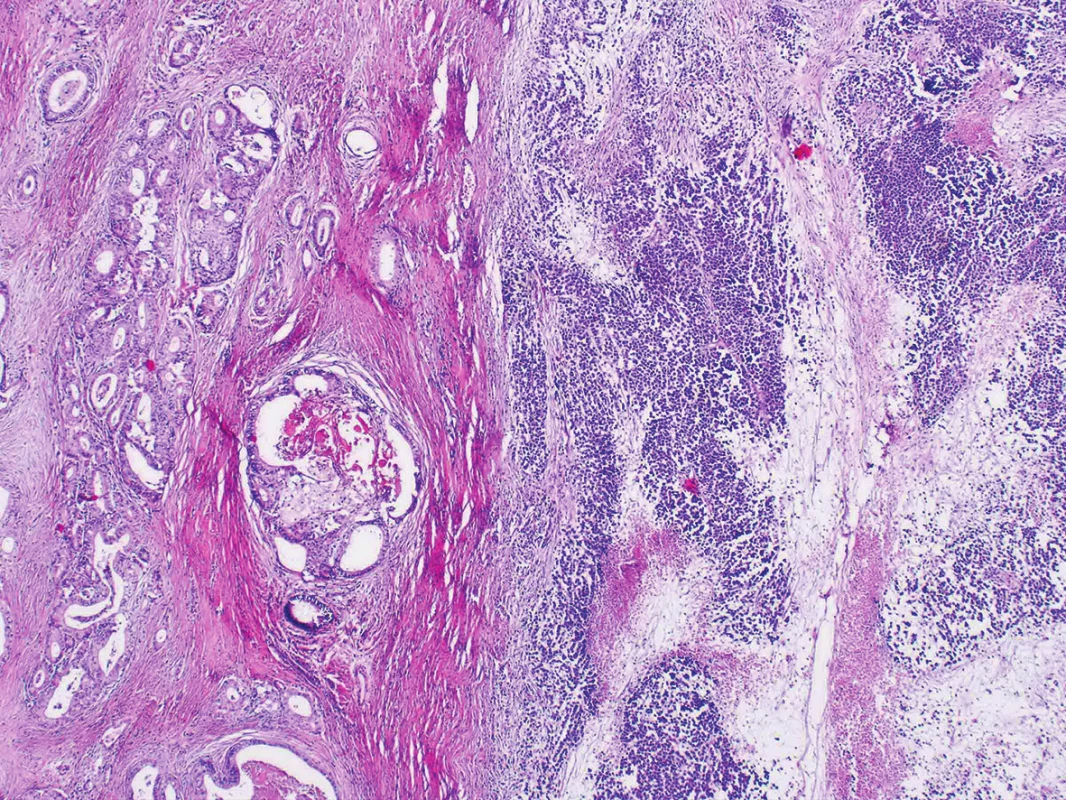

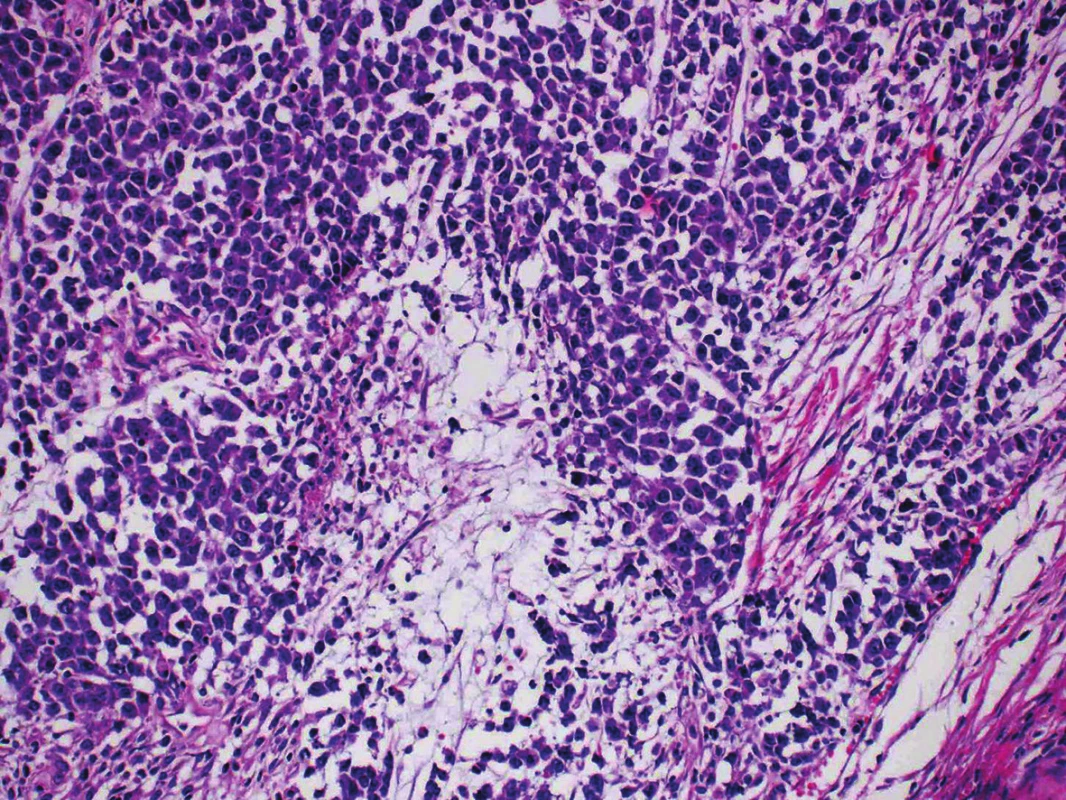

Microscopic examination of both ovaries revealed structures of well differentiated endometrioid carcinoma with extensive mucinous differentiation, comprising 35 % of the tumor area. Moreover, in the left ovary large areas of undifferentiated tumor with variable amounts of necrosis were found, consisting of medium-sized oval cells arranged in sheets, showing cellular dyscohesion in some areas (Fig. 1). Tumor cells in these areas had variable amounts of amphophilic cytoplasm as well as irregular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 2). The mitotic activity was high, up to 70 mitoses per 10 high-power fields. The tumor stroma contained disperse, predominantly chronic inflammatory infiltrate. The microscopic findings in the fallopian tubes and uterus were without any significant changes. Corporal endometrium was atrophic with endometrial polyp without atypias.

1. Dedifferentiated carcinoma with undifferentiated and well-differentiated components (H&E, original magnification 40x).

2. Undifferentiated component consisting of dyscohesive atypical cells arranged in sheets. (H&E, original magnification 400x).

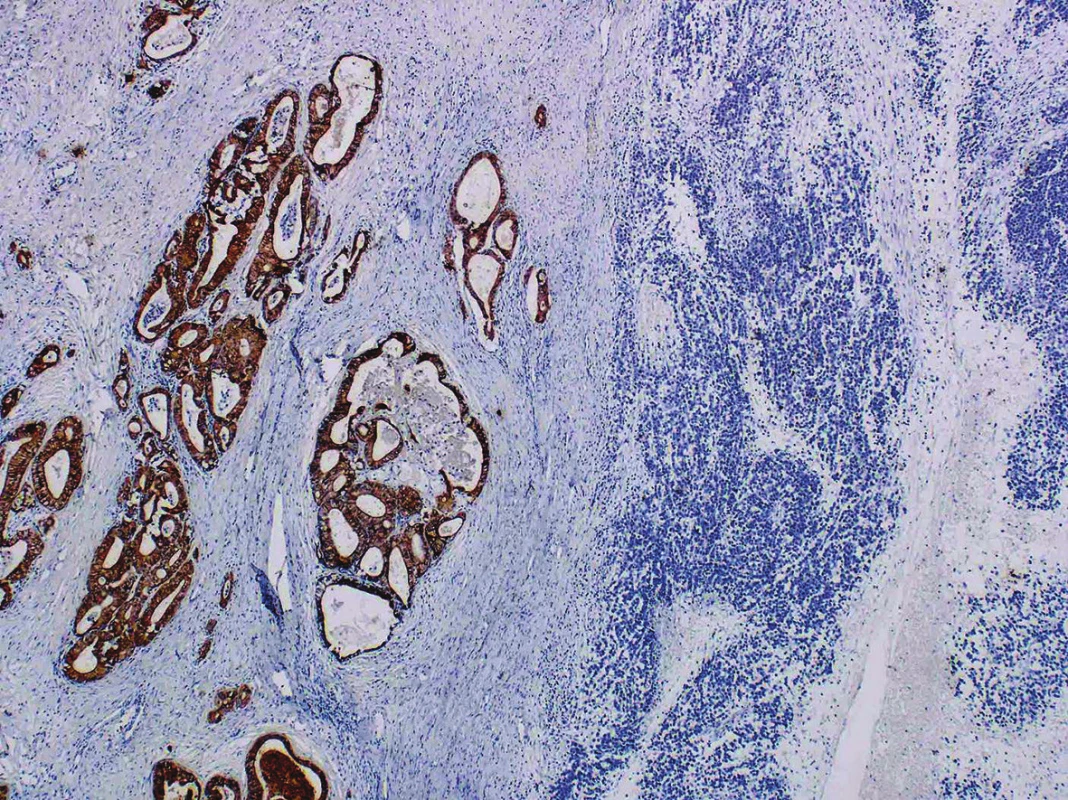

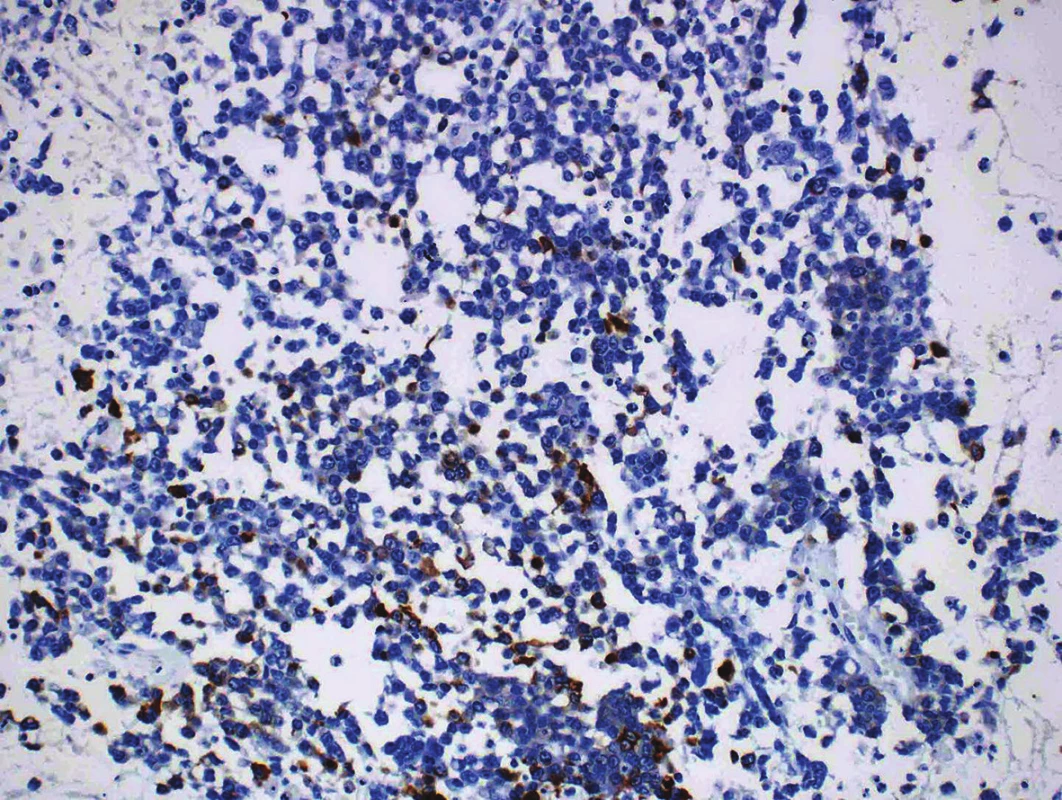

Immunohistochemical findings of both tumor components differed from each other. The well-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma showed diffuse expression of cytokeratin AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 18, and focal positivity of EMA (Fig. 3). Estrogen and progesterone receptors were positive in 30 % and 40 % of nuclei of the tumor cells, respectively. The cells in the undifferentiated component were almost diffusely positive for vimentin and focally positive for cytokeratin 18, in up to 15 % of the tumor cells. EMA, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, WT-1, estrogen and progesterone receptors, actin, desmin, S100 protein, BerEP4, HNF1-β, SALL 4, Oct-4, LCA, chromogranin and synaptophysin were all negative (Fig. 4). Both tumor components exhibited positive nuclear staining for the MMR proteins (MLH-1, MSH-2, MSH-6, PMS-2), negativity of PAX8 and weak nuclear p53 positivity in scattered cells and moderate nuclear positivity in sporadic cells, in keeping with the “wild-type” expression. The nuclear expression of INI-1 and Brg-1 was retained in both components. The Ki-67 proliferation index in the well-differentiated component was about 5 %, and in the undifferentiated component it was up to 80 % of tumor cells.

3. Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 positivity in well-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma and negativity in an undifferentiated component (original magnification 40x)

4. Focal expression of cytokeratin 18 in an undifferentiated component (original magnification 200x).

DISCUSSION

Undifferentiated and dedifferentiated carcinoma of the ovary and endometrium are clinically aggressive and, presumably, often misdiagnosed neoplasms (1-4). According to the WHO classification, undifferentiated carcinoma is defined as a malignant epithelial tumor showing no differentiation of any specific Müllerian cell type (2). Undifferentiated carcinoma either occurs in a pure form, or it can be associated with a second component of low-grade (FIGO grade 1 or 2) endometrioid carcinoma, and in the ovary possibly in combination with low-grade serous carcinoma. In these cases, the tumor is called dedifferentiated carcinoma (2). The undifferentiated component is usually composed of intermediate-sized round to oval cells arranged in solid sheets, often with a dyscohesive pattern and without apparent glandular differentiation, sometimes with cells displaying rhabdoid features. The stroma is generally unapparent, however, some tumors can have a myxoid matrix. The presence of necroses and high mitotic activity are a common finding. Almost half of the undifferentiated carcinomas display microsatellite-instability with MLH1 promoter methylation and a loss of expression of mismatch repair proteins, most frequently MLH1 and PMS2, but sometimes MSH2/MSH6 (6). It has been suggested that undifferentiated carcinoma may be linked to the group of tumors belonging to hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma (Lynch) syndrome (7). Ovarian carcinomas most often associated with Lynch syndrome are either pure endometrioid carcinomas, mixed carcinomas with an endometrioid, mucinous or clear cell component, or pure clear cell carcinomas (8). In our case, the well-differentiated component revealed rather extensive mucinous differentiation, but the loss of MMR protein expression was not found and this case is not likely to be associated with Lynch syndrome.

In almost half of the cases of undifferentiated carcinomas inactivating mutations of the SMARCA4 (BRG1) or SMARCB1(INI1) genes were identified. These genes encode members of the SWI/SNF pathway, and are the likely molecular events underlying dedifferentiation. The gene inactivation results in a loss of Brg-1 or INI-1 protein expression in the undifferentiated component and is often accompanied by the loss of expression of PAX8 and estrogen receptors (9,10). Approximately one-quarter of dedifferentiated endometrial and ovarian carcinomas also show concurrent ARID1A and ARID1B gene inactivating mutations, with a consequent loss of protein expression in the undifferentiated component. One recent study suggested that ARID1A and ARID1B co-inactivation appears to represent a major alternative mechanism to BRG1 or INI1 inactivation in the progression from endometrioid to undifferentiated carcinoma (9).

Moreover, abnormalities of SMARCB1 (INI1) and SMARCA4 (BRG1) genes are supposed to be associated with rhabdoid morphology, which could be found in a subset of dedifferentiated/undifferentiated endometrial carcinomas (10). The loss of expression of the SMARCA4 (BRG1) may often be accompanied by a concomitant loss of SMARCA2 (BRM) expression, but no correlation was found between the SMARCA2 (BRM) expression and rhabdoid morphology, neither between the SMARCA4 (BRG1) nor SMARCA2 (BRM) expression and clinical outcome. Our case did not display any rhabdoid morphology and expression of INI-1 and Brg-1 was retained in both tumor components. Intact expression of Brg-1 with simultaneous absent expression of PAX-8 and ER (which was found in about 75 % of undifferentiated endometrial carcinomas, even in our case of dedifferentiated ovarian carcinoma) suggests that other mechanisms are likely to be involved in the loss of expression of these markers, which appear to represent the hallmarks of dedifferentiation (10).

The differential diagnosis of undifferentiated / dedifferentiated ovarian carcinoma includes high grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma (FIGO grade 3), serous carcinoma, and also tumors of other histogenesis such as some sarcomas, lymphoma or melanoma. Because poorly differentiated carcinomas are known to be heterogeneous in their antigen expression, several markers used in a panel may be needed to achieve a correct diagnosis.

The distinction between undifferentiated ovarian carcinoma and an endometrioid adenocarcinoma (FIGO grade 3) can be difficult, but the cytological features and architecture of the latter are rather different with typical solid sheets of dyscohesive small to intermediate-sized cells without any glandular, trabecular or nested architecture. In the dedifferentiated carcinoma there are not only solid areas present but also a low-grade glandular component (2). Immunohistochemically, the undifferentiated component usually shows a reduction in the expression of keratins and EMA, which are not only patchy and focal but in some cases are even absent, whereas endometrioid carcinomas should show strong diffuse staining throughout. Regarding the other markers; the expression of hormonal receptors is usually absent in undifferentiated carcinomas, but endometrioid adenocarcinoma (FIGO grade 3) could also be negative. The positive staining of vimentin is quite often found in both tumor types. In addition, in a minority of undifferentiated/dedifferentiated tumor cell components the expression of chromogranin and synaptophysin may be found (3).

Although endometrioid carcinomas (FIGO grade 3) are generally considered high-grade neoplasms with a poor prognosis, undifferentiated / dedifferentiated carcinomas exhibit an even more aggressive clinical course (3).

Other tumors which should be considered in the differential diagnosis of undifferentiated / dedifferentiated carcinoma include serous carcinoma. Serous carcinomas are commonly composed of solid masses of cells with slit-like spaces, and high grade nuclear atypias. In addition, papillary, glandular and cribriform areas are quite common. Immunohistochemically, serous carcinoma usually exhibits a nuclear expression of WT1 and PAX8, unlike undifferentiated carcinoma (5).

Malignant melanoma can be excluded by the positivity of melanoma markers, such as S100 protein, SOX10, HMB-45, and Melan-A. Moreover, melanomas are typically negative for antibodies against “epithelial” markers, such as cytokeratins.

The correct diagnosis of ovarian undifferentiated / dedifferentiated carcinoma is based on a combination of morphological features with immunohistochemical results, but the immunophenotype of these tumors is not specific and must be evaluated in the context of all other features.

In summary, we have described an additional case of dedifferentiated carcinoma of the ovary. Although this type of ovarian carcinoma is rare its correct diagnosis is important because of its aggressive clinical behavior and very poor prognosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by Ministry of Health, Czech Republic - conceptual development of research organization 64165, General Teaching Hospital in Prague, Czech Republic, by Charles University (Project Progres Q28/LF1, UNCE 204024), and by OPPK (Research Laboratory of Tumor Diseases, CZ.2.16/3.1.00/24509).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Correspondence address:

Kristýna Němejcová, MD, Ph.D.

Department of Pathology, First Faculty of Medicine Charles University and General Teaching Hospital in Prague

Studničkova 2, Prague 2, 12800, Czech Republic

tel.: +420224968632

email: kristyna.nemejcova@vfn.cz

Sources

1. Kurman RJ, Ellenson LH, Ronnett BM. Blaustein’s Pathology of the Female Genital Tract (6th ed). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2011 : 430-771.

2. Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Young RH, Herrington CS (Eds.). WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs (4th edn). IARC: Lyon; 2014 : 40-133.

3. Silva EG, Deavers MT, Bodurka DC, Malpica A. Association of low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of the uterus and ovary with undifferentiated carcinoma: a new type of dedifferentiated carcinoma? Int J Gynecol Pathol 2006; 25(1): 52-58.

4. Chen L, Pang S, Shen Y, Liu Z, Luan J, Shi Y, Liu Y. Low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary associated with undifferentiated carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014; 7(7): 4422-4427.

5. Boyd C, McCluggage WG. Low-grade ovarian serous neoplasms (low-grade serous carcinoma and serous borderline tumor) associated with high-grade serous carcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma: report of a series of cases of an unusual phenomenon. Am J Surg Pathol 2012; 36(3): 368-375.

6. Tafe LJ, Garg K, Chew I, Tornos C, Soslow RA. Endometrial and ovarian carcinomas with undifferentiated components: clinically aggressive and frequently underrecognized neoplasms. Mod Pathol 2010; 23(6): 781-789.

7. Garg K, Leitao MM Jr, Kauff ND, Hansen J, Kosarin K, Shia J, Soslow RA. Selection of endometrial carcinomas for DNA mismatch repair protein immunohistochemistry using patient age and tumor morphology enhances detection of mismatch repair abnormalities. Am J Surg Pathol 2009; 33(6): 925-933.

8. Chui MH, Ryan P, Radigan J, et al. The histomorphology of Lynch syndrome-associated ovarian carcinomas: toward a subtype-specific screening strategy. Am J Surg Pathol 2014; 38(9):1173-1181.

9. Coatham M, Li X, Karnezis AN, et al. Concurrent ARID1A and ARID1B inactivation in endometrial and ovarian dedifferentiated carcinomas. Mod Pathol 2016; 29(12):1586-1593.

10. Ramalingam P, Croce S, McCluggage WG. Loss of expression of SMARCA4 (BRG1), SMARCA2 (BRM) and SMARCB1 (INI1) in undifferentiated carcinoma of the endometrium is not uncommon and is not always associated with rhabdoid morphology. Histopathology 2017; 70(3):359-366.

Labels

Anatomical pathology Forensic medical examiner Toxicology

Article was published inCzecho-Slovak Pathology

2018 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Predictive diagnosis in breast cancer - What‘s new in 2018?

- Prediction of EGFR blockade responses in metastatic colorectal carcinoma

- Predictive diagnostics of gastric cancer in 2018

- Evaluation of inflammatory cells (tumor infiltrating lymphocytes – TIL) in malignant melanoma

- Dedifferentiated carcinoma of the ovary. A case report

- Nonfunctioning parathyroid carcinoma associated with parathyromatosis. A case report

- Czecho-Slovak Pathology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Evaluation of inflammatory cells (tumor infiltrating lymphocytes – TIL) in malignant melanoma

- Dedifferentiated carcinoma of the ovary. A case report

- Predictive diagnosis in breast cancer - What‘s new in 2018?

- Prediction of EGFR blockade responses in metastatic colorectal carcinoma

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career