-

Medical journals

- Career

Emergency peripartum hysterectomy – our 6 years of experience

Authors: R. Erin; D. Kulaksiz

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Health Sciences, Trabzon Kanuni Training and Research Hospital, Turkey

Published in: Ceska Gynekol 2022; 87(3): 179-183

Category: Original Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.48095/cccg2022179Overview

Objective: Peripartum hysterectomy is a life-saving procedure performed during and after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. The incidence of placental invasion anomaly is increasing in parallel with the increase in the number of births by cesarean section. It was aimed to evaluate the frequency, risk factors and outcomes of peripartum hysterectomy performed in a tertiary hospital. Materials and methods: Research data were obtained by a retrospective review of patient files. Patients who underwent peripartum hysterectomy because of postpartum hemorrhage in the Gynecology and Obstetrics Clinic of Trabzon Kanuni Training and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences, Turkey, were included in the present study. The patients were divided into two groups as those who underwent emergency peripartum hysterectomy (EPH) and those who did not. Demographic variables, fetal and maternal mortality, EPH indications, additional surgeries performed during EPH, and intra - or postoperative complications were collected. Pearson chi-square test was used for statistical analysis. Results: There were 22,464 deliveries, of which 13,514 were delivered vaginally and 8,950 by cesarean section. Peripartum hysterectomy was performed on 42 patients (vaginal 16, cesarean section 26). The most common EPH indications in both groups were placenta accreta spectrum (42.9/ 3.2%), followed by uterine atony (38.1/ 2.5%). The most common risk factor for EPH was found to be a history of previous cesarean sections. Conclusion: Placental invasion anomalies that cause severe postpartum hemorrhage are due to increased cesarean rates. Currently, the most common indication of EPH is placental invasion anomalies.

Keywords:

peripartum hysterectomy – Postpartum hemorrhage – placental invasion anomaly

Introduction

Peripartum hysterectomy is a life-saving procedure performed during and after a vaginal delivery or cesarean section to manage life-threatening obstetric bleeding and uterine sepsis. This ope ration was first successfully applied by Porro in 1871 [1]. Peripartum hysterectomy was frequently performed in the middle of the 20th century, due to bleeding and urinary system injuries. Nowadays, its frequency has decreased due to the prominence of medical and uterus-sparing surgeries [2,3]. However, the incidence of placental invasion anomaly increases in parallel with the increase in the number of births by cesarean section. Today, these cases and uterine atony constitute most of the peri partum hysterectomies [4]. It was reported that the incidence of emergency peripartum hysterectomy was estimated as 0.7 per 1,000 births for high-income countries and 2.7 per 1,000 births for low-income countries [2]. In Turkey, the frequency of emergency peripartum hysterectomy (EPH) was reported in a range of 0.4–5/ 1,000 births [5–8]. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the frequency, risk factors, and outcomes of peripartum hysterectomy performed in a tertiary hospital in the Eastern Black Sea Region to guide treatments in future potential cases.

Materials and methods

Research data were obtained by a retrospective review of patient files. Patients who underwent peripartum hysterectomy because of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) in the Gynecology and Obstetrics Clinic of Trabzon Kanuni Training and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences, Turkey between January 2013 and January 2019 were included in this work. Local ethics committee approval (2019/ 32) was obtained from the Trabzon Kanuni Health Practice and Research Center Ethics Committee.

Exclusion criteria: patients who underwent hysterectomy for gynecological reasons, pregnancies under 20 weeks, and patients with incomplete hospital records were excluded from this study. Patients who underwent EPH after failing to control bleeding with medical treatment (using oxytocin, methergine, misoprostol, and carbetocin) and/ or with surgical treatment (such as uterine fundal massage, postpartum uterine curettage, Bakri balloon, b-Lynch, Hayman suture, hypogastric artery ligation, and uterine artery ligation) within 24 hours after vaginal delivery or cesarean section were included in the study. We divided patients into two groups, EPH applied and non-applied (control) patients. The data relating to age, body mass index (BMI), parity, weeks of gestation, previous cesarean section history, medical treatments applied before EPH, the duration between delivery and hysterectomy, estimated blood loss, operation time, the number of blood transfusions, hospital stay, APGAR scores of fetus in 1st and 5th minutes, fetal and maternal mortality, indications for EPH, additional surgeries performed during EPH, and complications during or after surgery were collected.

The gestational week of the patients was calculated according to their last menstrual period. The gestational week was calculated based on the fi rst-trimester ultrasonography for patients whose last menstrual period was uncertain and could not be remembered. The time between delivery and discharge was used as the length of hospital stay. According to the blood transfusion guidelines of the Ministry of Health, patients who were symptomatic and/ or had a hemoglobin value below 7 g/ dL were given a blood transfusion.

Statistical Package for Social Sciences 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. The distribution of data was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation) were used. Pearson chisquare test was used for the statistical analysis. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

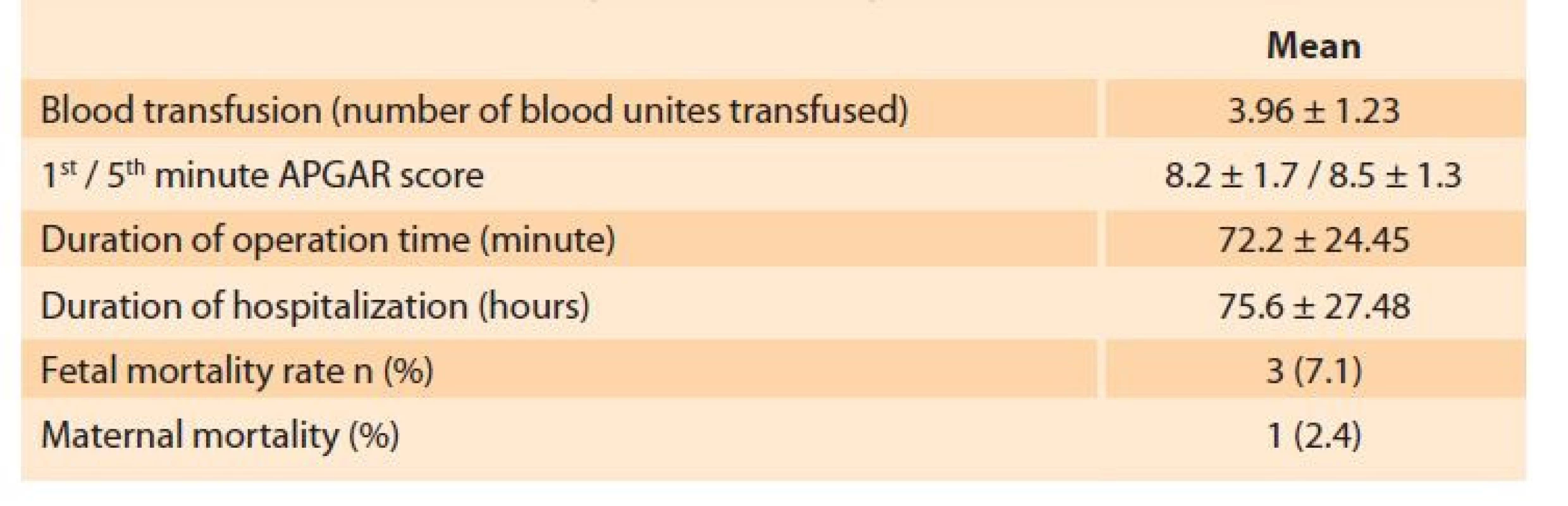

Out of 22,464 deliveries, 13,514 were accounted as vaginal deliveries and 8,950 were cesarean sections performed at our center in January in the years 2013–2019. We performed a peripartum hysterectomy (PH) procedure in 42 patients of which 16 were carried out after vaginal deliveries, and 26 were applied after cesarean section. Demographic data and operation information of the patients are given in Tab. 1. We divided the cases into two groups, those with and without PH.

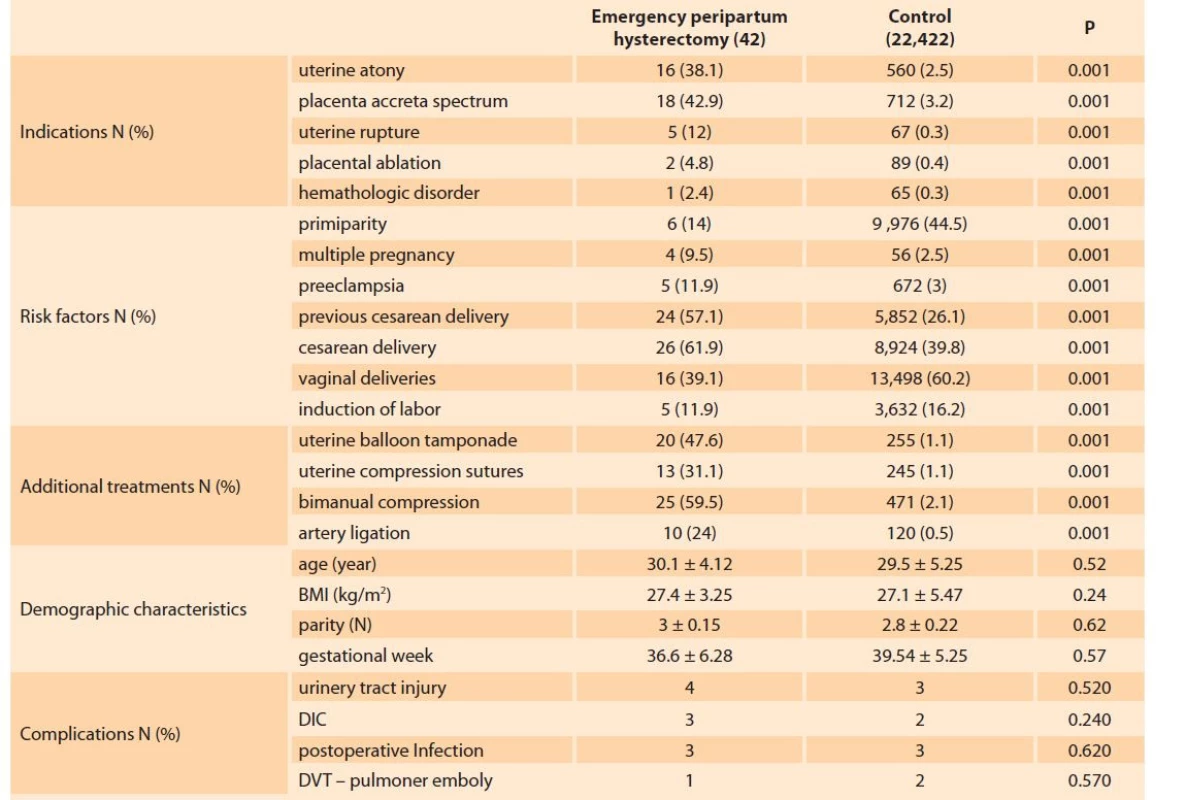

There was no significant difference amongst the groups in terms of age, parity, the duration between delivery and hysterectomy, estimated blood loss, number of blood transfusions, length of hospital stay, weeks of gestation, fetal death, and maternal death rates (P > 0.05) (Tab. 1). The most common PH indications in both groups were placenta accreata spectrum (PAS) in 18 patients (42.9%) for the PH group and 712 patients (3.2%) for the control group, followed by uterine atony in 16 patients (38.1%) and 560 patients (2.5%), respectively (Tab. 2).

1. Operation characteristics of peripartum hysterectomy.

Tab. 1. Operační charakteristiky peripartální hysterektomie.

The most common risk factor for EPH was previous cesarean section history as 24 patients (57.1%) for the PH group and 5,852 patients (26.1%) for the control group. Most risk was attributed to the patients with a vaginal delivery as 16% patients (39.1%) for the PH group and 13,498 patients (60.2%) for the control group. Bimanual compression was the most commonly applied additional hemostatic procedure in both groups. Uterine balloon tamponade was the second most common procedure in the experimental (case) group (Tab. 2).

2. Peripartum hysterectomy indications, risk factors and additional treatments.

Tab. 2. Indikace peripartální hysterektomie, rizikové faktory a doplňková léčba.

Data as shown mean ± std and percentage.

BMI – body mass index, DIC – disseminated intravascular coagulation, DVT – deep vein thrombosisDiscussion

Emergency peripartum hysterectomy is performed because of placental invasion anomaly and postpartum hemorrhage [4]. Cesarean section rates, the most crucial risk factor for placental invasion anomaly, have increased in recent decades [9]. Parallel to this, the incidences of placental invasion anomalies have been rising over the years [10]. In the present study, the incidences, indications, risk factors, morbidity, and mortality rates of peripartum hysterectomy cases were evaluated. The prevalence of peripartum hysterectomy was 1.9/ 1,000 births in all deliveries in the current study. In the study of de la Cruz et al [11], the incidence of EPH in the world was reported as 0.61/ 1,000 births. In a different systematic review, the incidence of PH was reported as 1/ 1,000 births [2]. Thus, there has been a dispute in the trend of PH incidence. Although several studies reported that the incidences of PH increase over time, others said that the incidence rates do not change, even slightly, and may even decrease [12]. The increase in cesarean rates can explain the reports on the increasing trends over time in studies examining the incidence of EPH. Considering the improved treatments for uterine atony, the increased rate of EPH is even more surprising.

The incidence of PH was higher than the value reported in previous literature. In studies conducted in Turkey, the incidence of PH was determined as 0.29/ 1,000 births by Yücel et al [6] as 0.37/ 1,000 births by Kayabaşoğlu et al [7], as 0.36/ 1,000 births by Tapısız et al [8], as 4.68/ 1,000 births by Erdemoğlu et al [5] and as 6.1/ 1,000 births by Çağlayan et al [13]. In the study of Peker et al, a total of 28,9793 cases have been evaluated. They reported the prevalence as 0.5/ 1,000 patients [14]. Therefore, past literature demonstrated that the incidence of PH in Turkey seems to be higher than in the values reported for other countries. Our results also supported the findings obtained for Turkey. The most important reasons for higher incidence rates for Turkey can be explained by the increase in the spectrum of placenta accreta in parallel with the increasing number of cesarean sections as the patients are usually referred too late because of socioeconomic status and the health system [9,10].

Evaluating the cesarean and vaginal births separately, it was observed that the incidence value was changed. It was reported that the incidence of EPH was 0.1–0.3 per 1,000 births and 1.–8.9 per 1,000 births after vaginal and cesarean deliveries, respectively [15,16]. Çağlayan et al [13] reported the incidence of EPH after vaginal and cesarean deliveries as 2.7 and 7.1 per 1,000 deliveries, respectively. In this study, we obtained the incidence value as 1.2/ 1,000 births for vaginal deliveries and 2.9/ 1,000 births for cesarean sections. As our hospital is the referral hospital for the region, the referral of complicated cases seems to be effective at these rates.

Cesarean section is a known factor for EPH in most studies. Compared to women who had their first cesarean section, Silver et al found that women with a third cesarean were 1.4 times more likely to have EPH, women with a fourth cesarean section were 3.8 times more likely to have EPH, women with a fifth cesarean section were 5.6 times more likely to have EPH, and those with a sixth or greater cesarean section were found to have EPH reported at a probability of 15.2 times higher [10].

The effect of cesarean section on EPH may be direct and indirect. It was suggested that with a cesarean section in the current delivery, removal of the uterus might be a more accessible practice. However, in vaginal deliveries, practitioners are advised to try other methods of controlling bleeding before resorting to EPH [17]. One further pro bable explanation is that cesarean delive ries lead to increased placenta previa, accreta, and uterine rupture in future deliveries, all of which may lead to EPH [10].

Advanced maternal age, abnormal placentation, high parity, and cesarean delivery in a previous or current pregnancy are risk factors for a peripartum hysterectomy [18]. Huque et al examined PH risk factors and found that bleeding from placenta previa/ accreta (17%) had a higher risk of hysterectomy (17%) than uterine atony (3%). In the same study, the adjusted odds ratio for hysterectomy in women with placenta previa/ accreta was 3.2 (95% CI 2.7–3.8) compared with uterine atony [18].

An increased risk of hysterectomy associated with placental pathologies and cesarean section has been reported in several studies [19,20]. They have associated cesarean delivery with a four-fold higher probability of hysterectomy than vaginal delivery (AOR 4.3, 95% CI 3.6–5.0) [18]. In the current study, the values of parity, age, cesarean delivery, and previous cesarean section history show increased risk of EPH compared to the control group.

While the most common cause of EPH was identified as previously uncontrolled postpartum bleeding, most of the studies in recent years have reported that the most common indication is abnormal placentation compared to uterine atony [21]. Abnormal placentation, including placenta previa and placenta accreta, exceeds uterine atony as the major factor leading to bleeding and EPH. In a systematic review, 45% of bleeding and EPH cases have been reported to be caused due to abnormal placentation, and 29% corresponded to uterine atony [22]. Flood et al investigated EPH cases for the past four decades, and a significant increase in the placenta accreta rates was found [21].

In the present study, the most common cause of EPH was found to be placental invasion anomalies. In placenta accreta, placental tissue invades the myometrium. After birth, it remains firmly attached to the uterine wall and causes severe blood loss [18]. The time to attempt conservative treatment in placenta accrete is very limited, and therefore, obstetricians may switch directly to hysterectomy [18]. This situation explains the shorter time interval between postpartum hemorrhage diagnosis and hysterectomy in women with placenta previa/ accreta than other bleeding causes. Some obstetricians prefer a conservative treatment method for abnormal placentation and leave the placenta in place. However, this can lead to sepsis and secondary bleeding and ultimately to hysterectomy [23]. Cesarean section causes scarring of the uterus which predisposes to abnormal placentation in later pregnancies [24]. Therefore, the main indication for peripartum hysterectomy has shifted from uterine atony to placenta accreta in recent years, with the increase in cesarean delivery rates [21].

The maternal mortality rates during or after EPH were reported around 3% worldwide [25]. Although EPH is a rare event, evidence suggests that it increases with a sharp rise in cesarean sections. In addition, EPH requires more hospital staff , blood products, mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit admission, and longer hospital stay than vaginal or cesarean deliveries [26], and has a significant psychological impact on affected women [25].

In the current study, the most common complication after EPH was urinary tract injury and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). In a systematic review of Rossi et al, the most common intraoperative complication was urinary tract injury (33.4%), and the most common postoperative complication was DIC (20.4%). Thus, the current study results were compatible with the existing literature in terms of complications [22].

Reducing EPH rates is linked to the fight against PPH. PPC prevention strategies, medical and surgical applications can reduce EPH rates. For example, uterotonic administration, compression sutures, balloon tamponade, and myometrial resection, which have been described recently and reported in reducing the rate of EPH, may be applied in experienced hands and in selected patients [27].

Limitations of the research: Unfortunately, most literature data on EPH is based on retrospective data. We have also based our study on retrospective data. Therefore, the study may not reflect the total population, as data from a single-center are used. The small number of cases and the short follow-up years are also limitations. Therefore, the current study should be supported by future studies with a long follow-up period and large participation.

Conclusion

Placental invasion anomalies increase with increasing cesarean rates, and in this case, they cause severe postpartum hemorrhages. As a result, EPH rates increase. There are not enough studies reporting the incidence and risk factors of EPH in this region. Therefore, this study contributes new information on EPH incidence, risk factors, and preventive procedure data for this region. The results may be analyzed and used in the future for preventive measures of EPH cases.

ORCID autors

R. Erin 0000-0002-9488-5414

D. Kulaksiz 0000-0003-2351-1367

Submitted/ Doručeno: 14. 10. 2021

Accepted/ Přijato: 1. 4. 2022

Deniz Kulaksiz, MD

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Health Sciences

Trabzon Kanuni Training

and Research Hospital

Maras Street

61040, Trabzon

Turkey

Sources

1. Mesleh R. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy. 2009 [online]. Available from: http:/ / www. tandfonline.com/ doi/ full/ 10.1080/ 0144361986 6264.

2. van den Akker T, Brobbel C, Dekkers OM et al. Prevalence, indications, risk indicators, and outcomes of emergency peripartum hysterectomy worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2016; 128(6): 1281–1294. doi: 10.1097/ AOG.0000000000001736.

3. Turgut A. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: our experience with 189 cases. Perinat J 2013; 21(3): 113–118. doi: 10.2399/ prn.13.0213003.

4. Demirci O, Tuğrul AS, Yılmaz E et al. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy in a tertiary obstetric center: nine years evaluation. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2011; 37(8): 1054–1060. doi: 10.1111/ j.1447-0756.2010.01484.x

5. Erdemoğlu M, Kale A, Akdeniz N. Obstetrik nedenlerle acil histerektomi yapilan 52 olgunun analizi. Dicle Tıp Derg 2006; 33(4): 227–230.

6. Yucel O, Ozdemir I, Yucel N et al. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: a 9-year review. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2006; 274(2): 84–87. doi: 10.1007/ s00404-006-0124-4.

7. Kayabasoglu F, Guzin K, Aydogdu S et al. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy in a tertiary Istanbul hospital. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2008; 278(3): 251–256. doi: 10.1007/ s00404-007-0551-x.

8. Tapisiz OL, Altinbas SK, Yirci B et al. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy in a tertiary hospital in Ankara, Turkey: a 5-year review. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012; 286(5): 1131–1134. doi: 10.1007/ s00404-012-2434-z.

9. Eyi EG, Mollamahmutoglu L. An analysis of the high cesarean section rates in Turkey by Robson classification. J Matern Neonatal Med 2021; 34(16): 2682–2692. doi: 10.1080/ 147 67058.2019.1670806.

10. Silver RM, Branch DW. Placenta accreta spectrum. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(16): 1529–1536. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMcp1709324.

11. de la Cruz CZ, Thompson EL, O’Rourke K et al. Cesarean section and the risk of emergency peripartum hysterectomy in high-income countries: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2015; 292(6): 1201–1215. doi: 10.1007/ s004 04-015-3790-2.

12. Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Callaghan WM et al. Peripartum hysterectomy in the United States: nationwide 14 year experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012; 206(1): 63.e1–63.e8. doi: 10.1016/ j. ajog.2011.07.030.

13. Özcan HÇ, Uğur MG, Balat Ö et al. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: single center ten-year experience. J Matern Neonatal Med 2017; 30(23): 2778–2783. doi: 10.1080/ 14767 058.2016.1263293.

14. Peker N, Turan G, Aydin E et al. Analysis of patients undergoing peripartum hysterectomy for obstetric causes according to delivery methods: 13-year experience of a tertiary center. Dicle Tıp Derg 2020; 47(1): 122–129. doi: 10.5798/ dicletip.706086.

15. Zelop CM, Harlow BL, Frigoletto FD Jr et al. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993; 168(5): 1443–1448. doi: 10.1016/ S0002-9378(11)90779-0.

16. Sahin S, Guzin K, Eroğlu M et al. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: our 12-year experience. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014; 289(5): 953 – 958. doi: 10.1007/ s00404-013-3079-2.

17. Whiteman MK, Kuklina E, Hillis SD et al. Incidence and determinants of peripartum hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108(6): 1486–1492. doi: 10.1097/ 01.AOG.0000245445.36116.c6.

18. Huque S, Roberts I, Fawole B et al. Risk factors for peripartum hysterectomy among women with postpartum haemorrhage: analy sis of data from the WOMAN trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018; 18(1): 186. doi: 10.1186/ s12884-018-1829-7.

19. Campbell SM, Corcoran P, Manning E et al. Peripartum hysterectomy incidence, risk factors and clinical characteristics in Ireland. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016; 207 : 56–61. doi: 10.1016/ j.ejogrb.2016.10.008.

20. Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P et al. Cesarean delivery and peripartum hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 2008; 111(1): 97 – 105. doi: 10.1097/ 01.AOG.0000296658.832 40.6d.

21. Flood KM, Said S, Geary M et al. Changing trends in peripartum hysterectomy over the last 4 decades. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 200(6): 632.e1–632.e6. doi: 10.1016/ j.ajog.2009.02.001.

22. Rossi AC, Lee RH, Chmait RH. Emergency postpartum hysterectomy for uncontrolled postpartum bleeding: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 115(3): 637–644. doi: 10.1097/ AOG.0b013e3181cfc007.

23. Chantraine F, Langhoff-Roos J. Abnormally invasive placenta – AIP. Awareness and pro-active management is necessary. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013; 92(4): 369–371. doi: 10.1111/ aogs.12130.

24. Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM. Clinical risk factors for placenta previa-placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997; 177(1): 210–214. doi: 10.1016/ s0002-9378(97)70463-0.

25. de la Cruz CZ, Coulter ML, O’Rourke K et al. Women’s experiences, emotional responses, and perceptions of care after emergency peripartum hysterectomy: a qualitative survey of women from 6 months to 3 years postpartum. Birth 2013; 40(4): 256–263. doi: 10.1111/ birt.12070.

26. Knight M. Peripartum hysterectomy in the UK: management and outcomes of the associated haemorrhage. BJOG 2007; 114(11): 1380 – 1387. doi: 10.1111/ j.1471-0528.2007.01507.x.

27. Sebghati M, Chandraharan E. An update on the risk factors for and management of obstetric haemorrhage. Womens Health (Lond) 2017; 13(2): 34–40. doi: 10.1177/ 1745505717716860.

Labels

Paediatric gynaecology Gynaecology and obstetrics Reproduction medicine

Article was published inCzech Gynaecology

2022 Issue 3-

All articles in this issue

- Relationship between urethrovesical junction mobility changes and postoperative progression of stress urinary incontinence following sacrospinous ligament fixation – a subanalysis of a multicentre randomized study

- Screening for congenital defects and genetic diseases of the fetus at University Hospital in Olomouc and sending/ reporting to the National register of reproductive health in the Czech Republic

- Timing of caesarean section and its impact on levator ani musle avulsion at the first subsequent vaginal birth – a pilot study

- Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome – rare case of malignancy of dysgenetic gonads

- Hydronephrosis as a symptom of clinically silent ureteral endometriosis

- Cesarean scar pregnancy

- Systemic lupus erythematosus and secondary antiphospholipid syndrome in native sisters with reduced fertility

- Fertility sparing approach in young women with endometrial cancer

- Balloon vaginoplasty as a minimally invasive method in the management of vaginal aplasia

- Ovarian tumors and genetic predisposition

- Steroid metabolome and multiple pregnancy

- Recenze knihy Pôrodníctvo

- Prof. Alois Martan, MD, DrSc. – 70-year-old

- Emergency peripartum hysterectomy – our 6 years of experience

- Czech Gynaecology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Cesarean scar pregnancy

- Hydronephrosis as a symptom of clinically silent ureteral endometriosis

- Ovarian tumors and genetic predisposition

- Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome – rare case of malignancy of dysgenetic gonads

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career