-

Medical journals

- Career

Smoking in women with chronic vaginal discomfort is not associated with decreased abundance of Lactobacillus spp. but promotes Mobiluncus and Gardnerella spp. overgrowth – secondary analysis of trial data including microbiome analysis

Authors: Tužil J. 1,2; Filková B. 1; Malina J. 3; Kerestes J. 4; Doležal T. 1,5

Authors‘ workplace: Value Outcomes Ltd., Prague, Czech Republic 1; First Medical Faculty, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 2; Aeskulab k. s., Prague, Czech Republic 3; Nature Laboratories, Ltd., Husinec, Czech Republic 4; Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic 5

Published in: Ceska Gynekol 2021; 86(1): 22-29

Category: Original Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.48095/cccg202122Overview

Background: Smoking is considered a risk factor for bacterial vaginosis. It is currently unknown which parameters of the vaginal environment are affected and how smoking triggers the disease.

Aim of the study: The primary objective is to estimate the effect size of smoking on vaginal pH and the Nugent score in patients with chronic vulvovaginal discomfort prior to the development of episode of vaginosis. The secondary goal is to investigate the effect of smoking on individual microscopic parameters of the vaginal environment and on subjectively reported symptoms of vaginal discomfort.

Methods: Smoking reported by patients was tested as a predictor, using multivariate logistic and ordinal logistic regression analysis on a dataset from the first visit of a randomized trial NCT04171947, which enrolled patients with intermediate vaginal environment. We tested the primary hypothesis (odds ratio (OR) for vaginal pH > 4.5 and Nugent score > 3 in smokers) at the significance level á = 5%. For exploratory analyses of the effect of smoking on the parameters of the vaginal environment, á was corrected as per Bonferoni.

Results: In a cross-sectional sample of 250 women after adjusting for other risk factors, smoking had an impact on the Nugent score (OR = 3.3 (1.3–8.5), P = 0.011), while pH was not affected (OR = 1.2 (0.5–2.8), P = 0.698). Smoking was associated with the prevalence of clue cells (P < 0.000), Gardnerella spp. (P = 0.001) and Mobiluncus spp. (P = 0.001), while the prevalence of Lactobacillus remained unchanged (P = 0.049).

Conclusion: Contrarily to common assumptions, vaginal Lactobacillus is not directly affected by smoking, which rather promotes the growth of bacteria of Gardnerella and Mobiluncus spp. Given that other parameters remained unaffected, it appears that smoking leads to vaginal dysbiosis by creating specific favourable conditions for these two opportunistic pathogens.

Keywords:

Bacterial vaginosis – smoking – Nugent score – vaginal pH – vaginal flora – Lactobacillus – Gardnerella – Mobiluncus – human microbiome

Introduction

Vaginal microflora dominated by Lactobacillus species represent the main pillar of mucosal homeostasis [1–4]. Along with Lactobacillus, less frequent elements coexist on the vaginal mucosa including bacteria, yeast, protozoa and blood cells [2,5,6]. In healthy women, lactic bacteria actively maintain low pH by anaerobic glycolysis of mucosal glycogen deposits which, along with the production of hydrogen peroxide, restricts the spread of other strains [2,5]. Opportunistic pathogens are thus present in latent numbers unless the conditions favour their overgrowth [6]. The stability of such an ecosystem is inversely proportional to the community diversity [3,5].

Contrarily to lay assumption, vaginal mucosa is a dynamic environment. Natural fluctuations in the composition relate to pregnancy and menstruation. In the course of life, vaginal mucosa is also repeatedly exposed to secretions, hormonal changes, and external influences; some of which have immediate negative effect on the ecosystem stability [7]. In healthy women, however, the microenvironment presents a tendency to spontaneously normalize towards Lactobacillus-dominated microflora [5] and short episodes of bacterial infection resolve spontaneously [7].

The specific conditions allow other strains – typically Mobiluncus and Gardnerella species, to compete with symbiotic Lactobacillus. Albeit often asymptomatic [8], roughly one third of patients with this intermediate flora progress to bacterial vaginosis [7,9] during which the bacteria exceed 100 - to 1,000-fold the numbers seen in healthy women [1].

Globally, bacterial vaginosis is the most common vaginal infection among women of reproductive age [10] having a significant impact on their quality of life [11]. Bacterial vaginosis is also responsible for problematic conception [12,13] adverse pregnancy outcomes [6,8], and increased risk of sexually transmitted infections [14–16], which imposes a large economic burden on society [10].

The treatment strategies for bacterial vaginosis are few [17] and they fail in over one half of patients [17,18]. Moreover, the repeated use of antibiotics represents a risk of the spread of resistant species. From the perspective of public health, the prevention of bacterial vaginosis is vital. Several risk factors have been identified and their avoidance is encouraged via health education [19]. In the common practice, smoking is considered one of them, although the epidemiological evidence is restricted to exploratory analyses burdened with multiple testing. Hellberg et al [20] showed roughly three-fold risk of bacterial vaginosis in smokers. The diagnosis was determined using Amsel criteria not allowing to uncover the impact of smoking on individual parameters. More detailed results were reported by Alnaif et al [21] describing the association between smoking and semiquantitative score developed by Nugent et al [22]. Again, smoking increased the risk about three-fold. Bradshaw et al [23] showed a dose-dependent relationship between the amount of cigarettes smoked and the risk of increased Nugent score in women and their female partners. Taken together, we know that smoking is associated with bacterial vaginosis in observational studies but we do not know what parameters of vaginal environment are affected and how is vaginosis triggered. We do not know if smoking favours pathogenic bacteria, if it restricts the symbiotic organisms and protective leukocytes, or if it acts directly on the mucosal pH.

Material and methods

Our primary hypothesis is that, among patients visiting outpatient gynaecology clinics for vulvovaginal discomfort, smokers have higher odds of Nugent score of > 3 and vaginal pH > 4.5. We further test the relationship between self-reported current smoking, individual subjective symptoms and individual microscopic parameters of the vaginal microenvironment.

This is a secondary analysis of the data from the first visit of the clinical trial MAT072017 [24] (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04171947) which took place in 14 outpatient gynaecology clinics in the Czech Republic in 2018. We included premenopausal patients aged 18 to 55 attending outpatient gynaecology for vulvovaginal discomfort. The subjects had negative pregnancy test, were not breastfeeding, with no antibiotics during the previous month, no bleeding of unknown aetiology, no severe infection requiring antibiotic treatment, and without diabetes mellitus or any oncological condition. For more details, refer to the Clinical Trials registry.

At the first visit, the patients signed informed consent and consent to the processing of personal information. The patients then filled in questionnaires, rated their symptoms on the scale 0 to 4, and underwent initial general examination, their medical history was assessed, pH measurements were taken, and wet mounts were prepared. In all patients, pH was determined using uniform gynaecology test strips (MColorpHast, Merck, Germany) according to a predefined procedure. Wet mounts were prepared from the posterior vaginal wall using a cotton swab. Fixed and blinded slides (4-digit codes) from all study centers were transported to a central accredited laboratory (private accredited laboratory AeskuLab k.s., Prague). One slide was stained by Giemsa-Romanowsky and the other by Gram stain. The blinded slides were assessed by a trained microbiologist using an oil immersion lens, providing total magnification of 1,000×. The following elements were quantified by a microbiologist: squamous epithelial cells; clue cells; mixed flora; yeast as pseudomycelia; Gram neg. diplococci; fibrous Lactobacillus; Gardnerella; spirochetes; parabasal epithelial cells; leukocytes; yeast as blastospores; Gram pos. cocci in chains; Lactobacillus; Mobiluncus; Leptotrichia and Trichomonas vaginalis. The Nugent score was determined, according to Nugent et al [22] (Fig. 1). Pointwise semiquantitative rating was performed according to the laboratory standardized procedure. Briefly, the number of elements per field were categorized into 5 points. For Mobiluncus and Gardnerella, 0 = none; 1~tens; 2~hundreds, 3~thousands; and 4 means abnormal infection. For Lactobacillus, 0 = none; 1~10 to 15; 2~15 to 50, 3~50 to 100; and 4 means over 100 bacteria per field. All ratings were done by the same microscopists. Unclear findings were resolved by another independent expert.

1. Representative micrograms of the vaginal environment. For each patient, one slide was stained by Giemsa-Romanowsky and the other by Gram stain. The slides were assessed using an oil immersion lens, providing total magnifi cation of 1,000X. Nugent scores (NS) were determined according to Nugent et al [22]. Panels A and B represent a microscopic image of bacterial vaginosis. Panels C and D show a normal environment. Panel A: NS = 10 (2+, 4+, 3+); Panel B: NS = 8 (0, 4+, 0) is a typical Gardnerella infection; Panel C: NS = 1 (3+, 0, 0); Panel D: NS = 0 (4+, 0, 0) with frequent rod- -like Lactobacillus. The arrows indicate high diversity mucosal flora typical for higher NS.

Obr. 1. Reprezentativní mikroskopické snímky vaginálního prostředí. U každé pacientky byly provedeny dva stěry, jeden byl obarven dle Giemsy-Romanowského a druhý dle Grama. Roztěr na sklíčku byl odečten imerzním objektivem pod 1 000násobným celkovým zvětšením. Nugentovo skóre (NS) bylo spočteno dle Nugenta et al [22]. Panely A a B představují pacientky s mikroskopickým obrazem bakteriální vaginózy. Panely C a D ukazují normální prostředí. Panel A: NS = 10 (2+, 4+, 3+); Panel B: NS = 8 (0, 4+, 0) je typickou infekcí bakterie Gardnerella; Panel C: NS = 1 (3+, 0, 0); Panel D: NS = 0 (4+, 0, 0) s častými tyčinkami rodu Lactobacillus. Šipky ukazují smíšenou slizniční flóru typickou pro zvýšené NS.![Representative micrograms of the vaginal environment.

For each patient, one slide was stained by Giemsa-Romanowsky and the other by Gram stain. The slides were assessed using an oil

immersion lens, providing total magnifi cation of 1,000X. Nugent scores (NS) were determined according to Nugent et al [22]. Panels

A and B represent a microscopic image of bacterial vaginosis. Panels C and D show a normal environment. Panel A: NS = 10 (2+, 4+,

3+); Panel B: NS = 8 (0, 4+, 0) is a typical Gardnerella infection; Panel C: NS = 1 (3+, 0, 0); Panel D: NS = 0 (4+, 0, 0) with frequent rod-

-like Lactobacillus. The arrows indicate high diversity mucosal flora typical for higher NS.<br>

Obr. 1. Reprezentativní mikroskopické snímky vaginálního prostředí.

U každé pacientky byly provedeny dva stěry, jeden byl obarven dle Giemsy-Romanowského a druhý dle Grama. Roztěr na sklíčku

byl odečten imerzním objektivem pod 1 000násobným celkovým zvětšením. Nugentovo skóre (NS) bylo spočteno dle Nugenta

et al [22]. Panely A a B představují pacientky s mikroskopickým obrazem bakteriální vaginózy. Panely C a D ukazují normální prostředí. Panel A: NS = 10 (2+, 4+, 3+); Panel B: NS = 8 (0, 4+, 0) je typickou infekcí bakterie Gardnerella; Panel C: NS = 1 (3+, 0, 0); Panel D:

NS = 0 (4+, 0, 0) s častými tyčinkami rodu Lactobacillus. Šipky ukazují smíšenou slizniční flóru typickou pro zvýšené NS.](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image_pdf/2c4c9e52f19f9bac32aaeedf9960053a.png)

Current smoking was reported with the patient by the gynaecologist via an electronic case-report form based on the interview with the patient. The smoking status recorded in the electronic case report forms was verified during monitoring visits against the patient’s medical record; any inconsistency was reconciled with the gynaecologist.

The hypothesis was tested in the cross-sectional sample using multivariate logistic regression (binary outcomes) and ordinal logistic regression (pointwise outcomes) at á level 0.05. The same was used to test the relationship between smoking and individual symptoms. The association between smoking and individual microscopic parameters was tested at á level 0.005 (corrected as per Bonferoni). The estimates were adjusted to the prevalence of patient-reported psychological distress, BMI, age, recent menstruation, recent coitus, multiple male sexual partners, soap with normal pH, regular usage of tampons and presence of a female sexual partner, using multivariate regression analysis. These factors were considered potential confounders based on a) the baseline differences between smokers and non-smokers and b) risk factors previously published in the literature. The data was complete thanks to thorough monitoring of the trial MAT072017. No imputation was done.

We report in line with the STROBE statement [25].

Results

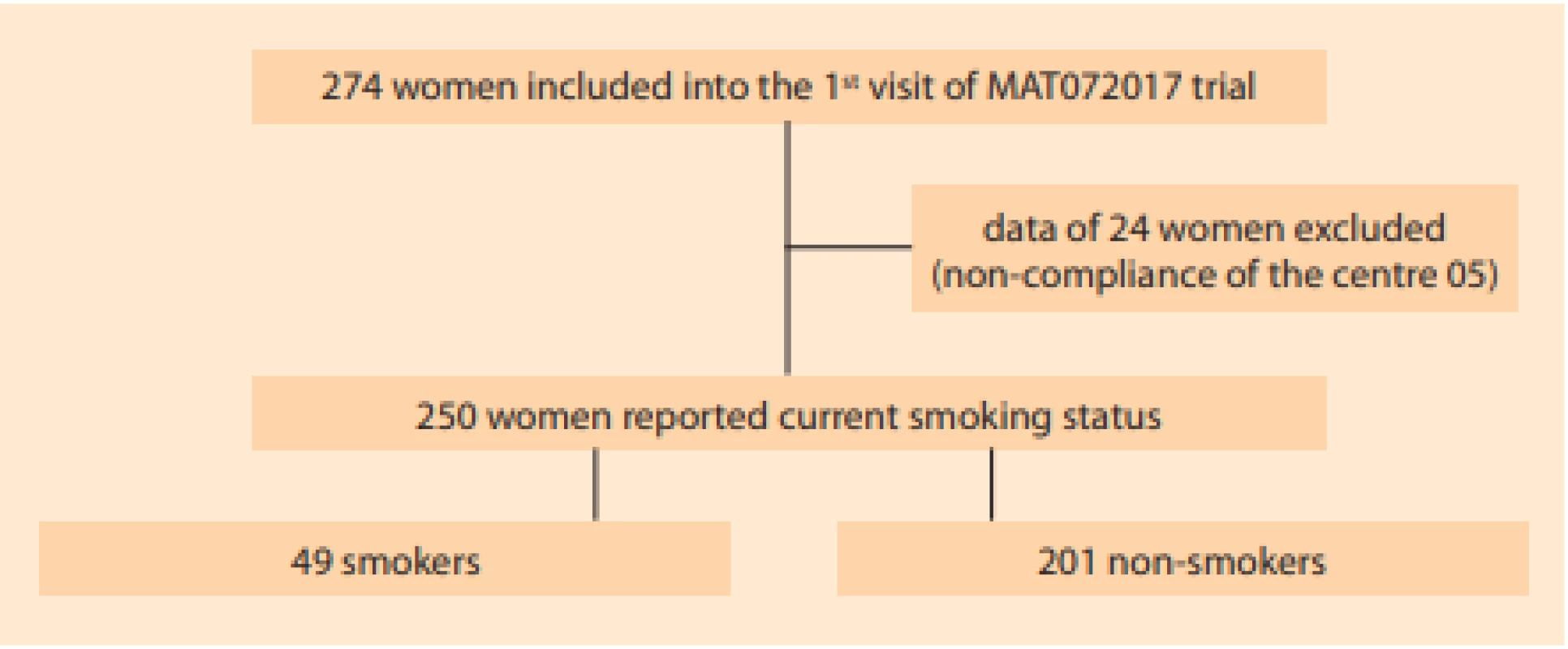

Of 274 patients enrolled in 14 outpatient gynaecology clinics, the data of 24 were excluded from the analysis due to repeated non-compliance of one centre. Of 250 patients attending out-patient gynaecology for vulvo - vaginal discomfort fulfilling the abovementioned criteria, 136 had vaginal pH > 4.5 (107/201 non-smokers vs. 29/49 smokers). Seventy-two subjects had Nugent score > 3 (51/201 non-smokers vs. 21/49 smokers) (Fig. 2). Smokers reported psychological distress (depression, anxiety, bereavement, divorce, job difficulties) roughly twice more often. The remaining characteristics did not differ significantly between smokers and non-smokers (Tab. 1).

2. Patient flow. The data of 24 women (entire centre) were excluded from the analysis for repeated non-compliance of this centre uncovered during several on-site monitoring visits.

Obr. 2. Výběr subjektů. Data 24 pacientek (zařazených v jediném centru) byla vyřazena z analýzy pro opakované porušení protokolu zkoušejícími v tomto centru.

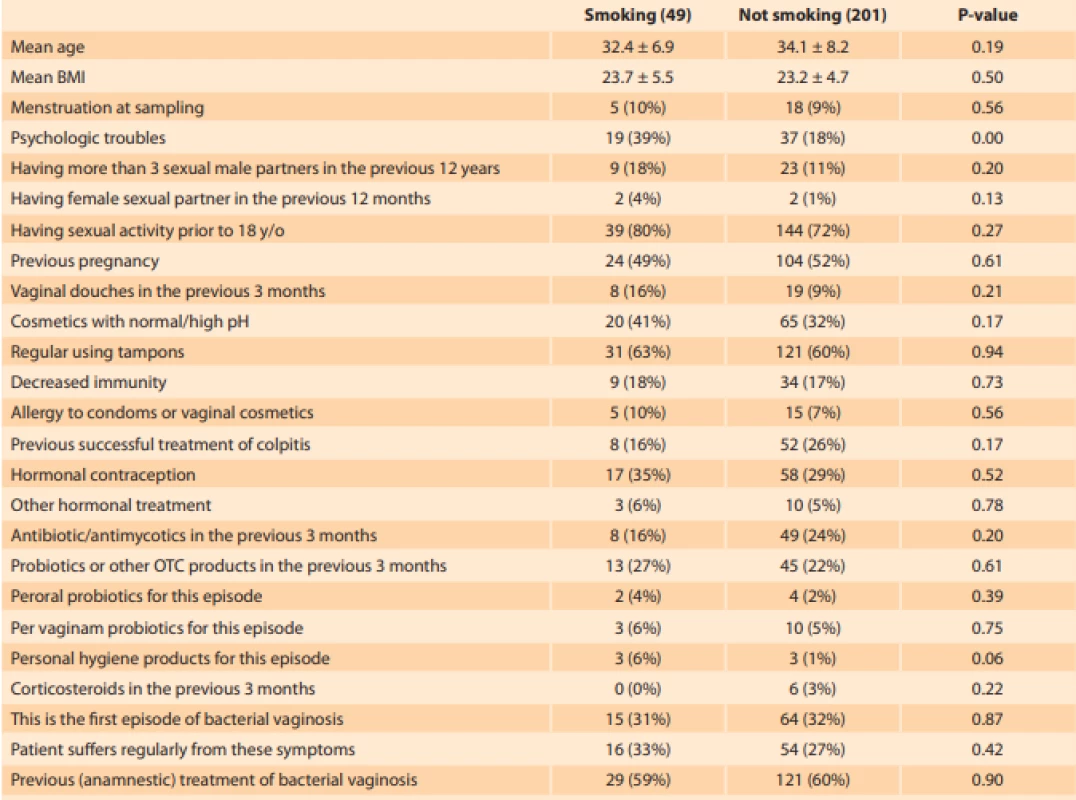

1. Characteristics of smokers and non-smoker attending out-patient gynaecology for vulvovaginal discomfort. The diff erences were tested via Chi2 or t-tests. The smokers suff ered more frequently from self-reported psychologic difficulties. The remaining overall characteristics are balanced.

Tab. 1. Charakteristiky pacientek kuřaček a nekuřaček navštěvujících ambulantní gynekologické ordinace z důvodu vulvovaginálního diskomfortu. Rozdíly byly testovány pomocí Chí kvadrát testu. Kuřačky reportovaly častěji psychologické obtíže, zbývající charakteristiky byly vyvážené.

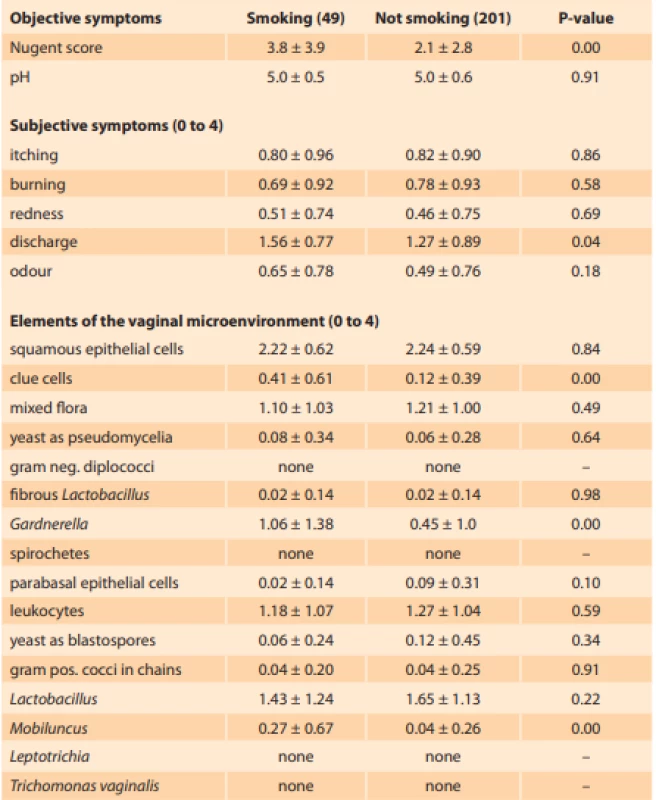

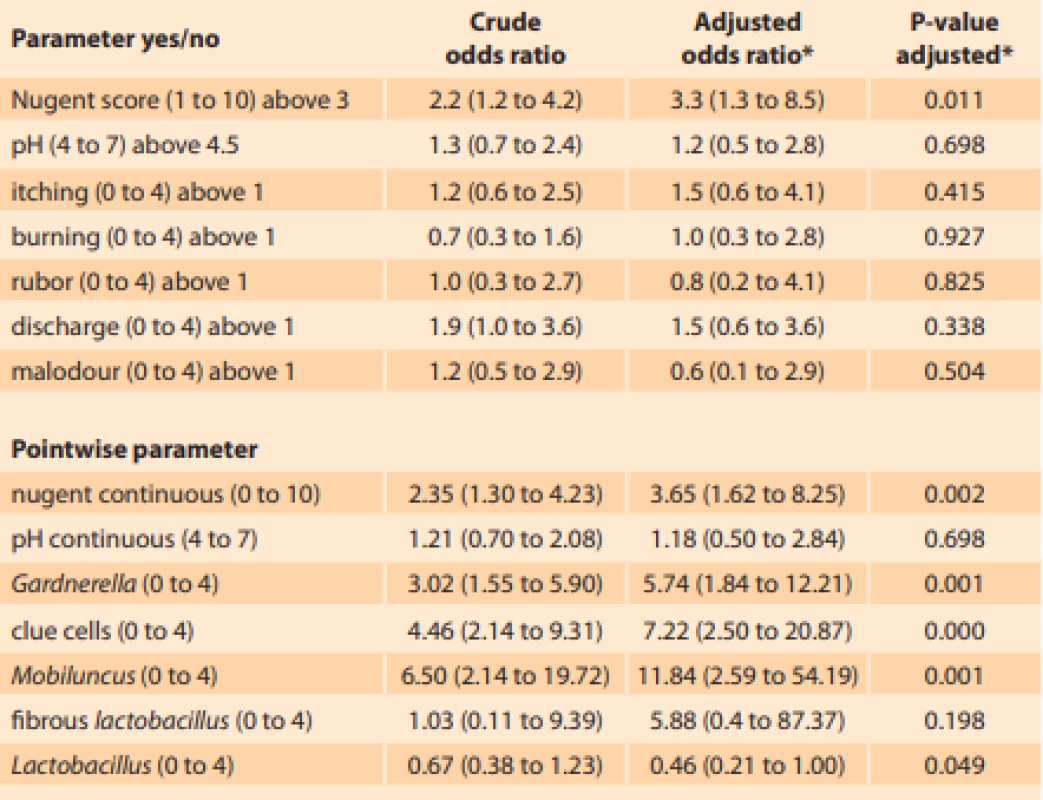

Comparing the differences in outcomes between smokers and non-smokers, we identified higher mean Nugent score and more severe discharge in smokers. The vaginal microenvironment in smokers was characterized by higher abundance of clue cells, Gardnerella species and Mobiluncus species (Tab. 2). The multivariate adjustment showed that smoking was associated with a 3.3-fold (1.3–8.5) higher odds of abnormal Nugent score (adjusted to psychological distress, BMI, age, recent menstruation, recent coitus, multiple male sexual partners, soap with normal pH, usage of tampons and presence of a female sexual partner) (Tab. 3). The estimate remains significant even after further adjustment to previous pregnancy, vaginal douching, allergy to pessary or condoms, use of hormonal contraception, antibiotics, antimycotics or corticosteroids (P = 0.04).

2. Differences in symptoms and elements of vaginal environment between smokers and non-smokers are represented as mean values ± SD

Tab. 2. Rozdíly mezi kuřačkami a nekuřačkami v příznacích a zastoupení mikroskopických prvků vaginálního prostředí jsou vyjádřeny jako průměr ± směrodatná odchylka

The smokers had signifi cantly higher mean Nugent score and more severe discharge. Vaginal microenvironemnt in smokers was characterized by higher abundance of clue cells, Gardnerella species and Mobiluncus species.

Pacientky kuřačky měly v průměru významně vyšší Nugentovo skóre a závažnější výtok. Vaginální mikroskopické prostředí u kuřaček je charakterizováno vyšším zastoupením klíčových buněk, Gardnerella spp. a Mobiluncus spp3. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for increase in individual parameters of the vaginal environment between 201 non-smokers and 49 smokers.

Tab. 3. Očištěné a neočištěné poměry šancí pro jednotlivé parametry vaginálního prostředí u 201 nekuřaček a 49 kuřaček.

The eff ect of smoking (yes/no) on individual parameters was investigated using logistic regression and ordinal logistic regression. The alpha was corrected for multiple testing for all analyses except for the primary hypothesis testing of the pH (binary) and Nugent score (binary).

Vliv kouření (ano/ne) na jednotlivé parametry byl testován pomocí logistické a ordinálně logistické regrese. Hladina alfa byla očištěna o mnohočetné testování u všech analýz kromě testu primární hypotézy u pH (binární) a Nugentova skóre (binární)

*adjusted to: psychological distress, BMI, age, recent menstruation, recent coitus, multiple male sexual partners, soap with normal pH, usage of tampons, female sexual partner.Increased vaginal pH was not associated with subjectively reported smoking (P = 0.577). None of the subjective symptoms are associated with smoking. Among 15 microscopic parameters, only the presence of clue cells, Gardnerella spp. and Mobilluncus spp. are associated with smoking. The reduction in Lactobacillus content is not associated with smoking.

Discussion

Smoking is known to largely affect human microbiome, notably with respect to oral, airway and gut health [26]. We show that, in addition to bacterial vaginosis [20], smoking is also associated with abnormal microflora during chronic recurrent vulvovaginal discomfort.

To date, a specific role of smoking in the aetiology of bacterial vaginosis has not been described. A pilot project using 16S rRNA gene sequencing in vaginal swabs of 20 smokers [27] aimed to identify the species that are most influenced by smoking. The study suggests that smoking correlates with decreased mucosal colonization by symbiotic Lactobacillus spp. and smoking cessation may help restore normal microflora in women already suffering from bacterial vaginosis. Contrarily to this finding, smoking was not related with vaginal pH, nor with the decrease in Lactobacillus content in our cohort of women suffering from recurrent vaginal discomfort. Our results indicate that smoking generates favourable conditions for pathogenic bacteria rather than unfavourable conditions for symbiotic Lactobacillus. Adjusted regression analysis based on the semi-quantitative microscopy shows that Gardnerella and Mobiluncus content increases in smokers along with the frequency of clue cells. Our result complements previous findings and shows that smoking promotes Gardnerella and Mobiluncus growth prior to the development of the clinical episode of bacterial vaginosis.

Our cohort was selected with the aim to represent a typical patient consulting the outpatient gynaecology clinic. Although roughly 70% women in our cohort had suffered with previous episodes of bacterial vaginosis, the swabs were taken prior to the development of the clinical episode or between the episodes. Thus, the conclusions drawn should not be extrapolated to bacterial vaginosis patients. Another limitation is that our sample consisted exclusively of Caucasian women which may somehow limit generalisation in other ethnic groups in which the microbiome dynamic follows different rules [4,28]. Third, inherent to observational research, our conclusion relies on the assumption of no unmeasured confounding which cannot be proved. A randomized study of smoking, however, is and will not be achievable with respect to the ethical considerations.

Conclusion

To conclude, we hope to have presented a piece of evidence on the role of smoking in the development of vaginal dysbiosis. A recent metabolomic study [29] shows increased concentration of nicotine metabolites and other amine compounds on the vaginal mucosa of smokers. Biogenic amine compounds have the ability to increase the virulence of latent opportunistic strains that are present even in healthy women. Further research should focus on the molecular mechanism and triggers responsible for Gardnerella and Mobiluncus overgrowth, notably with respect to smoking-cessation strategies such as nicotine-replacement therapy.

Declaration of interests

J.T. and B.F. are employees of Value Outcomes, a consultancy and research organization that designed, monitored and conducted the primary randomized trial on behalf of the sponsor Nature Laboratories Ltd., T.D. is the director of Value Outcomes. J.M. is the director of the laboratory that performed blinded analysis of the vaginal swabs, J.K. is a co-owner of the Nature Laboratories Ltd. that provided data from the randomized trial MAT072017. There are no competing interests relevant to the analysis, conclusion or interpretation of the data.

Submitted/Doručeno: 27. 10. 2020

Accepted/Přijato: 8. 1. 2021

Jan Tužil

Value Outcomes Ltd.

Václavská 12

120 00 Prague

Czech Republic

Sources

1. Donders GG. Definition and classification of abnormal vaginal flora. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007; 21 (3): 355–373. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.01.002.

2. Bautista CT, Wurapa E, Sateren WB et al. Bacterial vaginosis: a synthesis of the literature on etiology, prevalence, risk factors, and relationship with chlamydia and gonorrhea infections. Mil Med Res 2016; 3 (1): 4. doi: 10.1186/s40779 - 016-0074-5.

3. Fredricks DN, Fiedler TL, Marrazzo JM. Molecular identification of bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med 2005; 353 (18): 1899–1911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043802.

4. Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z et al. Vaginal micro - biome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108 (Suppl 1): 4680–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107.

5. Greenbaum S, Greenbaum G, Moran-Gilad J et al. Ecological dynamics of the vaginal microbiome in relation to health and disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019; 220 (4): 324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.1089.

6. Paavonen J, Brunham RC. Bacterial vaginosis and desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. N Engl J Med 2018; 379 (23): 2246–2254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1808418.

7. Brotman RM, Ravel J, Cone RA et al. Rapid fluctuation of the vaginal microbiota measured by Gram stain analysis. Sex Transm Infect 2010; 86 (4): 297–302. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.040592.

8. Leitich H, Kiss H. Asymptomatic bacterial vagiosis and intermediate flora as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007; 21 (3): 375–390. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.005.

9. Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Nugent RP et al. Characteristics of three vaginal flora patterns assessed by gram stain among pregnant women. Vaginal infections and prematurity study group. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 166 (3): 938–944. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378 (92) 91368-k.

10. Peebles K, Velloza J, Balkus JE et al. High global burden and costs of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis 2019; 46 (5): 304–311. doi: 10.1097/OLQ. 0000000000000972.

11. Bilardi JE, Walker S, Temple-Smith M et al. The burden of bacterial vaginosis: women’s experience of the physical, emotional, sexual and social impact of living with recurrent bacterial vaginosis. PLoS One 2013; 8 (9): e74378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074378.

12. Perslev K, Msemo OA, Minja DT et al. Marked reduction in fertility among African women with urogenital infections: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2019; 14 (1): e0210421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210421.

13. Swidsinski A, Verstraelen H, Loening-Baucke V et al. Presence of a polymicrobial endometrial biofilm in patients with bacterial vaginosis. PLoS One 2013; 8 (1): e53997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053997.

14. Suehiro TT, Malaguti N, Damke E et al. Association of human papillomavirus and bacterial vaginosis with increased risk of high-grade squamous intraepithelial cervical lesions. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2019; ijgc–2018–000076. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2018-000076.

15. Kaida A, Dietrich JJ, Laher F et al. A high burden of asymptomatic genital tract infections undermines the syndromic management approach among adolescents and young adults in South Africa: implications for HIV prevention efforts. BMC Infectious Diseases 2018. [online]. Available from: https: //bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-018-3380-6.

16. McKinnon LR, Achilles S, Bradshaw CS et al. The evolving facets of bacterial vaginosis: implications for HIV transmission. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses 2019. [online]. Available from: https: //www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/AID.2018.0304.

17. Muzny CA, Kardas P. A narrative review of current challenges in the diagnosis and management of bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis 2020; 47 (7): 441–446. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.00 00000000001178.

18. Xiao B, Niu X, Han N et al. Predictive value of the composition of the vaginal microbiota in bacterial vaginosis, a dynamic study to identify recurrence-related flora. Sci Rep 2016; 6 (1): 26674. doi: 10.1038/srep26674.

19. Chen Y, Bruning E, Rubino J et al. Role of female intimate hygiene in vulvovaginal health: global hygiene practices and product usage. Womens Health (Lond) 2017; 13 (3): 58–67. doi: 10.1177/1745505717731011.

20. Hellberg D, Nilsson S, Mårdh PA. Bacterial vaginosis and smoking. Int J STD AIDS 2000; 11 (9): 603–606. doi: 10.1258/0956462001916461.

21. Alnaif B, Drutz HP. The association of smoking with vaginal flora, urinary tract infection, pelvic floor prolapse, and post-void residual volumes. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2001; 5 (1): 7–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-0976.2001.51002.x.

22. Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol 1991; 29 (2): 297–301. doi: 10.1128/JCM.29.2.297-301.1991.

23. Bradshaw CS, Walker SM, Vodstrcil LA et al. The influence of behaviors and relationships on the vaginal microbiota of women and their female partners: the WOW Health Study. J Infect Dis 2014; 209 (10): 1562–1572. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit664.

24. Tuzil J, Filkova B, Jircikova J et al. Tea extract vaginal ovule for intermediate flora: randomized blinded vehicle-controlled multicenter pilot clinical trial with microbiome analysis. J Biol Act Prod Nat 2020; 10 (5): 357–372. doi: 10.1080/22311866.2020.1839557.

25. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61 (4): 344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008.

26. Huang C, Shi G. Smoking and microbiome in oral, airway, gut and some systemic diseases. J Transl Med 2019; 17 (1): 225. doi: 10.1186/ s12967-019-1971-7.

27. Brotman RM, He X, Gajer P et al. Association between cigarette smoking and the vaginal microbiota: a pilot study. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14 : 471. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14 - 471.

28. Zhou X, Brown CJ, Abdo Z et al. Differences in the composition of vaginal microbial communities found in healthy Caucasian and black women. ISME J 2007; 1 (2): 121–133. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.12.

29. Nelson TM, Borgogna JC, Michalek RD et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with an altered vaginal tract metabolomic profile. Sci Rep 2018; 8 (1): 852. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14943-3.

Labels

Paediatric gynaecology Gynaecology and obstetrics Reproduction medicine

Article was published inCzech Gynaecology

2021 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Aspects of embryo selection and their preparation for the formation of human embryonic stem cells intended for human therapy

- Elevated serum concentrations of S100–A11 and AIF-1 in cervical dysplasia patients

- Serum concentrations of S100–A11 and AIF-1 are elevated in cervical cancer patients with lymph node involvement

- Combined peripartal pubic symphysis and sacroiliac joint separation

- Myomas in uterine rudiments in a patient with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome

- Current ethical aspects of absolute uterine factor infertility treatment using uterus transplantation

- Eating disorders in the ambulance of pediatric and adolescence gynecology

- Adverse events of PARP inhibitors

- 30th symposium on assisted reproduction with international participation and 19th Czech-Slovak conference on reproductive medicine, November 10–11, 2020, Brno, Brno

- Editorial

- In memoriam Karel Nouza, MD, DrSc.

- Smoking in women with chronic vaginal discomfort is not associated with decreased abundance of Lactobacillus spp. but promotes Mobiluncus and Gardnerella spp. overgrowth – secondary analysis of trial data including microbiome analysis

- Czech Gynaecology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Adverse events of PARP inhibitors

- Combined peripartal pubic symphysis and sacroiliac joint separation

- Aspects of embryo selection and their preparation for the formation of human embryonic stem cells intended for human therapy

- Eating disorders in the ambulance of pediatric and adolescence gynecology

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career