-

Medical journals

- Career

Breast implant rupture: A sports trauma report

Authors: A. Krajcová 1; K. Hurt 2; R. Kufa 3; M. Molitor 1

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Plastic Surgery, 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University Prague, Bulovka Teaching Hospital, head M. Molitor, MD, PhD 1; Department of OBGYN, 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University Prague, Bulovka Teaching Hospital, head prof. M. Zikán, MD, PhD 2; Perfect Clinic, Plastic Surgery dpt, Prague, head R. Kufa, MD 3

Published in: Ceska Gynekol 2020; 85(2): 116-119

Category: Case Report

Overview

Objective: Breast augmentation is one of the most commonly performed plastic surgery procedures worldwide. Because of the quality of the implant material, implant rupture may first occur about 10 years after implantation. Ruptured breast implants caused by competitive sport events are rare but should be considered in women athletes as a potential risk factor. The authors report a noteworthy case of this kind.

Design: Literature overview and case report.

Setting: Department of Plastic and Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1st faculty of Charls University, Bulovka hospital, Prague.

Methods: Evaluation of the literature and an observational study.

Conclusion: Breast implant ruptures are generally at high risk in competitive contact sports. We do not recommend the use of breast implants in women competing in contact sports such as boxing.

Keywords:

trauma – rupture – breast implant – boxing

INTRODUCTION

Breast implants are essential components for plastic and reconstructive surgery. They are mainly divided into three groups:

- Silicone gel-filled implants

- Textured saline-filled breast implants

- Hydrogel-filled breast implants

The first group has mostly been used in modern medicine since their invention by Cronin in the early 1960s. The implant could be placed within different layers of the breast, mainly divided into subglandular (denotes superficial to the pectoralis major muscle) and subpectoral (denotes deep to pectoralis major). Breast implant ruptures (BIRs) are rare in the first 10 years of use but occur more often in the following years [2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 12]. After 10 years, the rupture rate is about 10%. The rupture rate is dependent on the kind of augmentation/reconstruction, the brand and technique used and is surgeon sensitive. Other possible complications include capsular contraction, gel bleed, scarring, folding and changes in nipple sensitivity [5, 8]. BIRs can be divided into two main types: intracapsular and extracapsular [4]. Generally, about three-fourths of implant ruptures are intra-capsular and the remaining one-fourth extracapsular. Only 10% of the implants with intra-capsular ruptures progress to extracapsular rupture. The extracapsular rupture is often connected with the capsular contracture (on the Baker scale grade III or IV) [5, 6, 14].

CASE REPORT

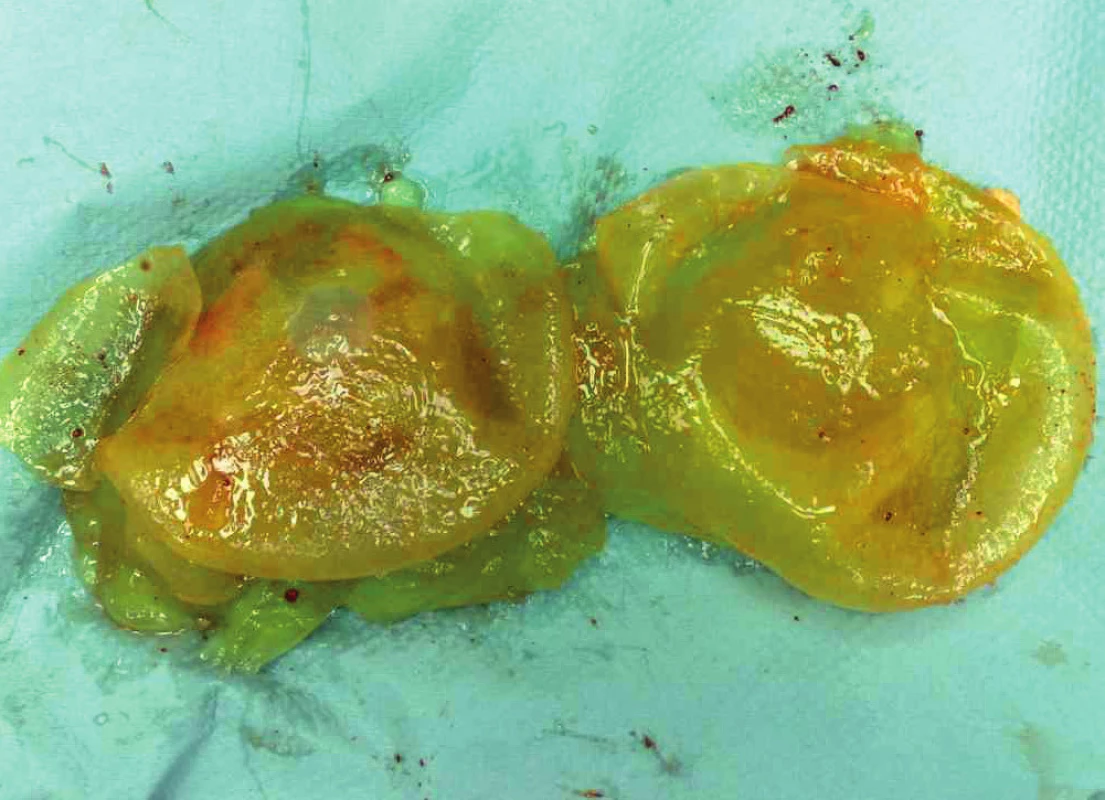

A 29-year-old patient was examined at our clinic for acute pain in her breasts after a sports injury. The patient was a professional female boxer who underwent breast subglandular augmentation 6 months before the injury. After augment-recovery, she had three competitions. She won the first two without incident (no notable injury) but her implants were injured in the third fight. A physical examination determined the ruptures (Baker grade IV, Fig. 1, Fig. 2). US examination was performed revealing the classic “snowstorm sign” of extracapsular rupture (Fig. 3). The patient’s status was notably altered: she had fever, dizziness, her c-reactive protein (CRP) was 105 and she had early symptoms of inflammation. The patient underwent immediate surgery, which confirmed the diagnosis of ruptured implants. Implants and implant capsules were removed and leaked silicone was evacuated (Fig. 4). Suction drains were inserted followed by administration of antibiotics. The patient’s postoperative status was normal and she was released two days after surgery (Fig. 5). The last question of the patient was when she could undergo the nose job. The patient has given written consent to publish data (including pictures) related to her case.

1. Patient at admission, Baker grade IV, front view

2. Patient at admission, Baker grade IV, side view

3. Ultrasound image of ruptured implant

5. Status after the reconstruction procedure

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of BIRs is possible using several methods [6]. The first is the physical examination. The sensitivity/specificity of this method is about 30–60%. Mammography is a relatively inexpensive and frequently used modality for women with and without breast implants. Extracapsular rupture with free silicone can easily be detected by mammography; however, the intracapsular is covered because of the density of silicone [4, 13]. Consequently, this method has serious limitations. More favourable methods in the diagnosis of implant ruptures are US and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Their sensitivity/specificity rates ranges from approximately 50–90% (US) and 80–90% (MRI). Concordance between US and MRI is as high as 85%. MRI is certainly the best method for diagnostics, although it has some limitations in contraindications and costs [5, 8, 10, 14, 15]. For the broader population, US is the most convenient method. Stepladder is the most reliabe ultrasonographic finding in breast implant intracapsular rupture, whereas snowstorm is the most reliable US finding in breast implant extracapsular rupture. If in doubt, a MRI can be used to judge the case [1, 4, 5, 8, 11]. We argue that the present case is important for two reasons. First, leakage of the silicon after the implant rupture could lead to inflammation, although the opposite opinion is often mentioned in databases. Second, breast implants should not be recommended for women involved in competitive contact sports in which the risk of injury is significant.

CONCLUSIONS

The frequency of sports injuries rises with the severity of the stress-strain state. Acute injuries often occur in contact situations, especially in competitive sports. Aesthetic implants and fillings could be at higher risk in such contexts. We briefly described possible complications of breast implants and mentioned appropriate diagnostics methods to detect BIRs. In our case-report of a very uncommon sports injury we have discussed potential problems of women who underwent breast augmentation in contact-sports.

We obtained the patient’s fully informed, written consent to publish the photos, materials and the whole case.

Corresponding author

Karel Hurt, MD, PhD

Department of OBGYN, Charles University

Bulovka teaching hospital

Budinova 2

180 00 Prague 8

Czech Republic e-mail: hurt@prahainfo.com

Sources

1. Caskey, CI., Berg, WA., Anderson, ND., et al. Breast implant rupture: diagnosis with US. Radiology. 1994, 190(3), p. 819–23.

2. Colombo, G., Ruvolo, V., Stifanese, R., et al. Prosthetic breast implant rupture: imaging – pictorial essay. Aesthetic Plast Surg, 2011, 35(5), p. 891–900. doi: 10.1007/s00266-011-9694-z. PubMed PMID: 21487917

3. Cook, RR., Bowlin, SJ., Curtis, JM., Hoshaw, SJ., et al. Silicone gel breast implant rupture rates: research issues. Ann Plast Surg, 2002, 48(1), p. 92–101.

4. Hillard, C., Fowler, JD., Barta, R., Cunningham, B. Silicone breast implant rupture: a review. Gland Surg, 2017, 6(2), p. 163–168. doi: 10.21037/gs.2016.09.12. PubMed PMID: 28497020; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5409893.

5. Hold, PM., Alam, S., Pilbrow, WJ., et al. How should we investigate breast implant rupture? Breast J, 2012, 18(3), p. 253–256.

6. Holmich, LR., Fryzek, JP., Kjoller, K., et al. The diagnosis of silicone breast-implant rupture – Clinical findings compared with findings at magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Plastic Surg, 2005, 54(6), p. 583–589. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000164470.76432.4f. PubMed PMID: WOS:000229690100001.

7. Chung, KC., Greenfield, M., Walters, M. Decision-analysis methodology in the work-up of women with suspected silicone breast implant rupture. Plastic Reconstruct Surg, 1998, 102(3), p. 689–695. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199809030-00011. PubMed PMID: WOS:000075605400011.

8. Lake, E., Ahmad, S., Dobrashian, R. The sonographic appearances of breast implant rupture. Clin Radiol, 2013, 68(8), p. 851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2013.03.014. PubMed PMID: 23623260.

9. Mallon, P., Ganachaud, F., Malhaire, C., et al. Bilateral poly implant prothese implant rupture: an uncommon presentation. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open, 2013, 1(4), p. e29. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0b013e318298e026. PubMed PMID: 25289223; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4173840.

10. Netscher, DT., Weizer, G., Malone, RS., et al. Diagnostic value of clinical examination and various imaging techniques for breast implant rupture as determined in 81 patients having implant removal. South Med J, 1996, 89(4), p. 397–404.

11. Park, AJ., Walsh, J., Reddy, PS., et al. The detection of breast implant rupture using ultrasound. Br J Plast Surg, 1996, 49(5), p. 299–301.

12. Quaba, O., Quaba, A. PIP silicone breast implants: rupture rates based on the explantation of 676 implants in a single surgeon series. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg, 2013, 66(9), p. 1182–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.05.003. PubMed PMID: 23725742.

13. Samuels, JB., Rohrich, RJ., Weatherall, PT., et al. Radiographic diagnosis of breast implant rupture: current status and comparison of techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg, 1995, 96(4), p. 865–877.

14. Tark, KC., Jeong, HS., Roh, TS., Choi, JW. Analysis of 30 breast implant rupture cases. Aesthetic Plast Surg, 2005, 29(6), p. 460–469; discussion 70–71. doi: 10.1007/s00266-004-0146-x. PubMed PMID: 16328645.

15. Weizer, G., Malone, RS., Netscher, DT., et al. Utility of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography in diagnosing breast implant rupture. Ann Plast Surg, 1995, 34(4), p. 352–361.

Labels

Paediatric gynaecology Gynaecology and obstetrics Reproduction medicine

Article was published inCzech Gynaecology

2020 Issue 2-

All articles in this issue

- Is the finding of endometrial hyperplasia or corporal polyp an mandatory indication for biopsy?

- Possibilities of objectivization of pelvic floor muscle exercises in patients with urine leakage after delivery

- Laparoscopic correction of isthmocele combined with ventrosuspensios of uterus

- Incidental occurrence of high grade serous tubal adenocarcinoma after prophylactic adnexectomy in benign gynecological surgery

- Enteral cystic duplicature in peripartum period – case report

- MODY diabetes and screening of gestational diabetes

- Hypoglycemia in oral glucose tolerance test in gestational diabetes mellitus screening – is it of any clinical importance?

- Modern terminology and classification of female pelvic organ prolapse

- The International Network of Obstetric Survey System

- Inflammatory bowel diseases in pregnancy

- 4. seminář reprodukční medicíny

- Výsledky voleb Výboru Sekce gynekologické endoskopie ČGPS ČLS JEP

- Breast implant rupture: A sports trauma report

- Czech Gynaecology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Is the finding of endometrial hyperplasia or corporal polyp an mandatory indication for biopsy?

- Modern terminology and classification of female pelvic organ prolapse

- Laparoscopic correction of isthmocele combined with ventrosuspensios of uterus

- MODY diabetes and screening of gestational diabetes

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career