-

Medical journals

- Career

Impact of cesarean section in a private health service in Brazil: indications and neonatal morbidity and mortality rates

Authors: M. A. Almeida 3; Edward Araujo Júnior 3; L. Camano 3; A. B. Peixoto 1,3; W. P. Martins 2; R. Mattar 3

Authors‘ workplace: Mário Palmério University Hospital, University of Uberaba (UNIUBE), Uberaba-MG 1; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine-São Paulo University, (FMRP-USP), Ribeirão Preto-SP 2; Department of Obstetrics, Paulista School of Medicine-Federal University of São Paulo (EPM-UNIFESP), São Paulo-SP, Brazil 3

Published in: Ceska Gynekol 2018; 83(1): 4-10

Overview

Objective:

To evaluate the incidence of, indications of, and maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality rates in cesarean sections in a private health service in Brazil.Design:

Retrospective and observational study.Setting:

Private health service in Vitória, Espírito Santo, Brazil.Methods:

The patients were interviewed using a structured questionnaire to determine maternal age, gestational age at the time of delivery, number of previous deliveries, type of delivery performed, duration of labor, indications for cesarean delivery, point at which cesarean section was performed, physician responsible for delivery, and maternal morbidity, fetal morbidity, and fetal mortality rates. A descriptive analysis of the data was conducted. Student‘s t-test was performed to compare quantitative variables, and Fisher‘s exact test was performed for categorical variables.Results:

A total of 584 patients were evaluated. Of these, 91.8% (536/584) had cesarean sections, while only 8.2% (48/584) had vaginal deliveries. There were no reports of forceps-assisted vaginal deliveries. In 87.49% of the deliveries, the number of gestational weeks was more than 37. In terms of indications for performing cesarean section, 48.5% were for maternal causes, 30.41% were for fetal causes, and 17.17% were elective. Maternal re-hospitalization due to puerperal complications was necessary in 10.42% of the vaginal deliveries and in 0.93% of the cesarean deliveries (p<0.001). Complications were observed in 18.75% of the vaginally delivered newborns and in 17.16% of those delivered by cesarean section. Of the newborns with complications at birth, 40.59% (41/101) had to be admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. There were no cases of maternal death. There were seven cases of fetal/neonatal death.Conclusion:

We observed that the vast majority of deliveries in the private sector are performed by cesarean section, without labor, and by the patient‘s obstetrician. We found no serious maternal complications or increased neonatal morbidity rates associated with cesarean section.Keywords:

Brazil, cesarean section, maternal complications, neonatal morbidityINTRODUCTION

The worldwide increase in the rate of cesarean sections is the result of multiple factors. In the United States, the rate of cesarean sections increased from 4.5% in 1965 to 32.9% in 2009 [15]. In Brazil, according to data from the World Health Organization, the rate of cesarean deliveries is 45.9% [10]. However, when distribution by social class is considered, the rates of cesarean deliveries are as high as 80% in higher social classes, mainly because of the higher number of elective cesarean sections performed [3, 10].

The reasons for performing elective cesarean section include fear of specific elements of labor and concern about maternal and fetal morbidity attributed to vaginal delivery [4]. Elective cesarean section has been associated with iatrogenic prematurity, complications arising from cesarean section scarring in future pregnancies, and repeat cesarean delivery [4]. For this reason, efforts have been made to avoid the first cesarean section.

Approximately 70% of cesarean sections in the United States of America (USA) occur in primigravida patients. The three main indications for undergoing a first cesarean section in the USA are prolonged labor (35%), non-reassuring fetal status (24%), and abnormal presentation (19%) [7]. In Brazil, Oliveira et al. [19] showed that in the public healthcare system, the existence of a prior cesarean delivery increases the risk of another cesarean section by a factor of approximately 16.99 (Odds ratio – OR = 16.99; 95%CI = 2.23–129.40).

Maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity rates increase with the number of cesarean sections performed [17]; these rates are higher in cases of emergency cesarean section [6] and when cesarean section is performed during the second phase of labor [1]. The most common maternal complications not associated with the anesthetic procedure are hemorrhage, uterine complications (infections, hematoma, seroma, and dehiscence), pelvic organ injury, and thromboembolism [11].

The objective of this study was to evaluate the incidence and indications for cesarean section, as well as maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality rate in a private health service in Brazil.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective, observational study in Vitória, Espírito Santo, Brazil. The patients selected for the study were parturients in a private health service. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP).

The patients were interviewed using a structured questionnaire administered during 6–18 months following delivery. Interviews were scheduled in advance and conducted in interviewees‘ homes or in several cases, by telephone. Selected women who could not be located were excluded.

The following variables were evaluated: maternal age, gestational age at the time of delivery (≤34 + 6 weeks, 35–37 + 6 weeks, 38–40 + 6 weeks, or ≥41 weeks), number of previous deliveries (1 delivery, 2–4 deliveries, or ≥5 deliveries), type of delivery (vaginal, cesarean section, or forceps), time in labor, indications for cesarean section, physician responsible for delivery (the patient‘s obstetrician or another obstetrician), and maternal morbidity, maternal mortality, fetal morbidity, and fetal mortality rates.

Maternal morbidity was defined as the presence of maternal complications following delivery (post-partum depression, post-partum headache, surgical wound infection, urinary tract infection, vesicouterine fistula, or mastitis) and the need for admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). We define maternal mortality as the death of a woman during pregnancy or within 42 days of delivery, with the exception of deaths due to accidental causes.

Fetal morbidity was defined as the presence of complications in the newborn following birth, such as jaundice, transient tachypnea, hypoglycemia, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, impetigo, other infections, the need for admission to the neonatal (ICU), intrapartum anoxia, or hyaline membrane disease. Stillbirths were defined as fetuses that were born dead, and deaths were defined as those neonates who died on or before the 28th day of life.

Data were transferred to an Excel 2003 worksheet (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and analyzed using PASW, version 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). First, a descriptive analysis was performed based on percentages (%), and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed on quantitative variables. Variables showing normal distribution are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), and variables showing non-normal distribution are presented as median and range. Categorical variables are expressed as absolute frequency and percentages and compared using Fisher‘s exact test. The level of significance in all tests was p < 0.05.

RESULTS

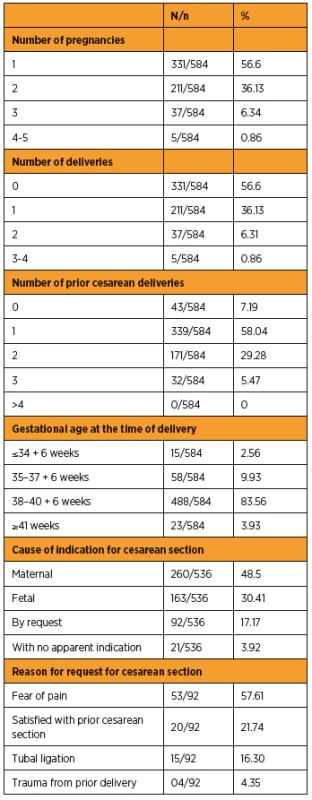

A total of 584 patients were evaluated during the study period. When the type of delivery was considered, 91.8% (536/584) were cesarean sections, while only 8.2% (48/584) were vaginal deliveries. There were no reports of forceps-assisted vaginal deliveries. In 74.63% (400/536) of the cases, patients did not go into labor and had to undergo cesarean section. The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

1. Characteristics of the study population

The most frequent reason for which cesarean delivery was indicated was cephalopelvic disproportion (21.82%), followed by a prior cesarean section (19.78%), gestational hypertension (4.66%), pre-gestational or gestational diabetes mellitus (1.48%), umbilical hernia (0.19%), an older primigravida (>35 years of age) (0.19%), a prior pelvic fracture (0.19%), and psychological depression (0.19%).

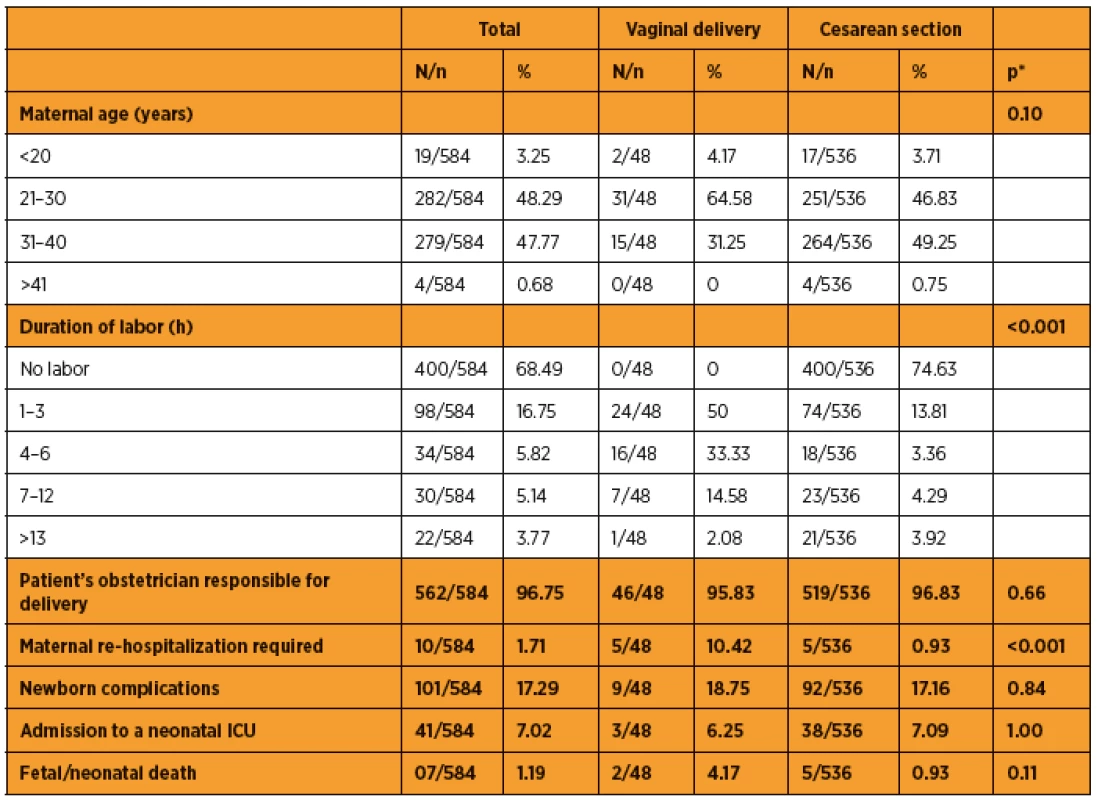

The most frequent fetal cause for an indication of cesarean delivery was functional dystocia (11.01%), followed by pelvic presentation (6.53%), acute fetal distress (3.74%), nuchal cord (2.99%), post-term pregnancy (>40 weeks) (2.05%), oligohydramnios (amniotic fluid index ≤5 cm) (1.49%), premature placental separation (1.30%), multiple births (0.68%), placenta previa (0.37%), and polyhydramnios (ILA ≥25 cm) (0.18%). Table 2 shows the characteristics of the population according to the type of delivery.

2. Characteristics of the population according to the type of delivery

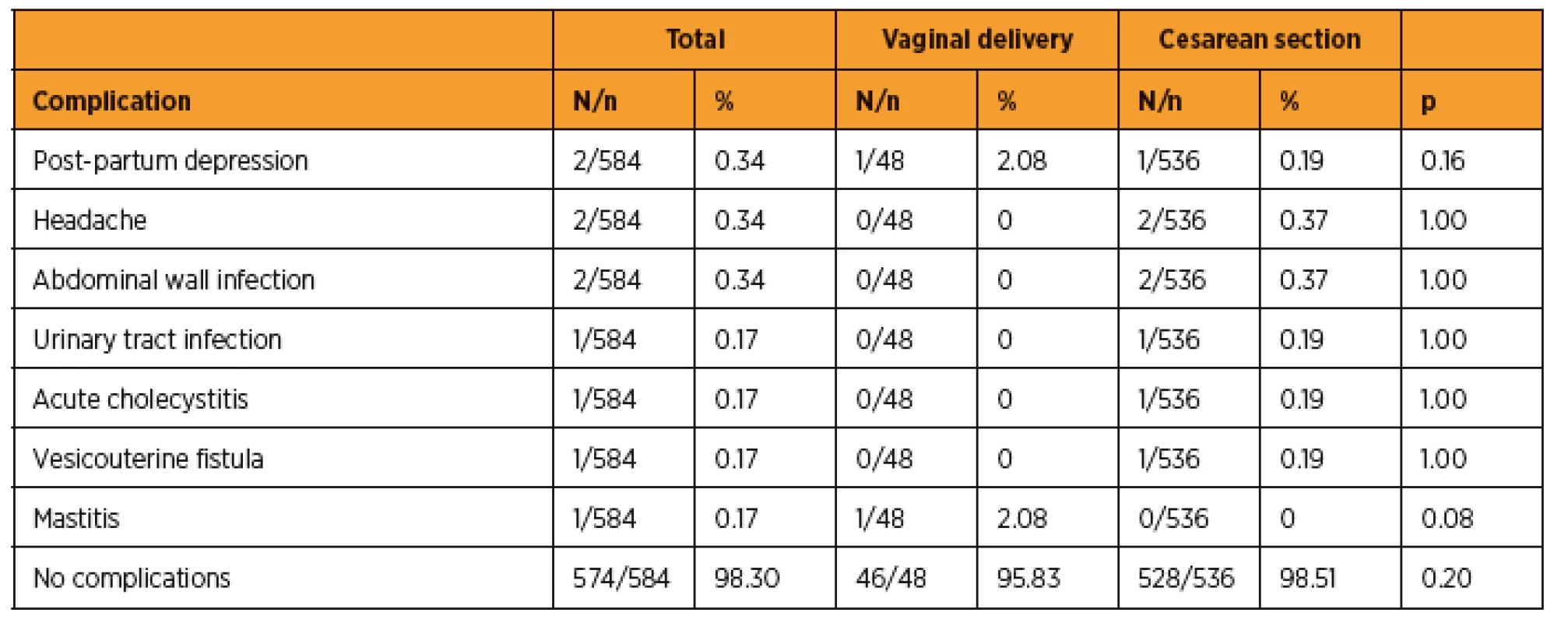

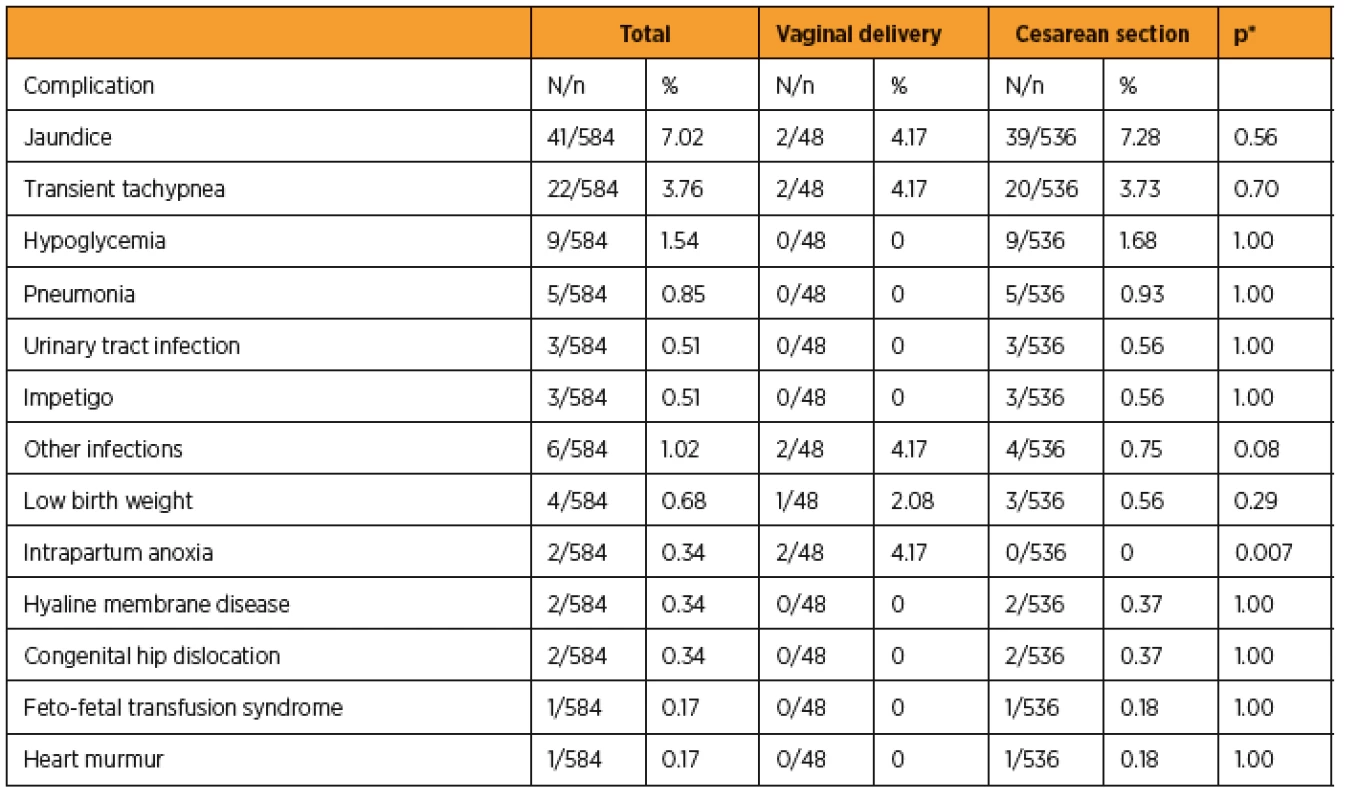

ICU: intensive care unit The incidence of maternal complications was 1.71% (10/584), while that of neonatal complications was 17.29% (101/584). Of the newborns who had complications at birth, 40.59% (41/101) had to be admitted to the NICU. There were no maternal deaths or requirement for admission to the ICU for any of the 584 patients. Of the 584 deliveries analyzed, 3 stillbirths and 4 newborn deaths were recorded: 2 (28.58%) from cardiopulmonary malformation, 2 (28.58%) from premature placental separation, 1 (14.28%) from genitourinary system malformation, 1 (14.28%) from prematurity, and 1 (14.28%) from septicemia. When gestational age was considered in the cases of the 7 newborns who died, 1 (14.28%) was born at <30 weeks, 3 (42.85%) were born between 30 and 34 weeks, 2 (28.58%) were born between 34 and 36 weeks, and 1 (14.28%) was born between 38 and 40 weeks. No deaths were recorded after 40 gestational weeks. Tables 3 and 4 show maternal and newborn complications according to the type of delivery, respectively.

3. Maternal complications according to the type of delivery

4. Newborn complications according to the type of delivery

DISCUSSION

The worldwide increase in cesarean delivery rates is evident in the literature. This increase is more evident in some countries, including Brazil, particularly among patients at higher socioeconomic levels [8].

In our study, we observed that 91.68% of the deliveries were cesarean sections, while only 8.22% were vaginal deliveries. The incidence of cesarean sections was significantly higher than the national average for cesarean deliveries (45.9%) [10]. According to the international literature, the incidence of cesarean sections ranges from 17.4% to 27.8% in Asian and European countries and from 26.3% to 30.3% in North American countries [10].

The indications for surgical deliveries coincide with those in the literature; however, the order of frequency is not always consistent. In our study, 48.50% of the cesarean section indications were for maternal causes, 30.41% were for fetal causes, 17.17% were by patient request, and 3.92% had no apparent indication. The most frequent indications for apparently justified maternal causes were cephalopelvic disproportion (21.82%) and a prior cesarean section (19.78%). Functional dystocia was the most frequent fetal cause (11.01%), followed by acute fetal distress (4.73%). Osava et al. [20] mentioned functional dystocia and cephalopelvic disproportion as the main reasons for cesarean delivery. In the USA, cephalopelvic disproportion accounted for 35% of the indications for cesarean section [16]. In Brazil, the incidence of cesarean delivery due to a prior cesarean delivery is higher than that in other countries; it is 43% in Campinas, S?o Paulo [5].

It is important to question cases in which cesarean section was indicated due to cephalopelvic disproportion in our study, given that 21.09% of the cesarean deliveries performed had no clinical indication and 74.63% of the patients whose deliveries were evaluated did not go into labor. Today, clinical criteria are no longer the only important factors in indications for type of delivery. Advances in obstetrics and medicine, in general, along with social factors and other criteria such as fear of pain, the comfort of a pregnant woman and her obstetrician, repeat cesarean section, and even tubal ligation have the same or greater weight as clinical criteria in the indication for cesarean section. However, we should be cautious when indicating cesarean delivery as it can be associated with a series of long-term perinatal and maternal complications, such as prematurity, endometriosis, uterine complications, injuries to pelvic organs, abnormal placental implantation, uterine rupture, chronic pelvic pain, and irregular menstruation [2, 9, 13, 14].

Maternal morbidity rates are higher in cesarean deliveries than in vaginal deliveries [18]. However, in our study, we did not find serious maternal complications directly associated with cesarean sections, such as hypovolemia, puerperal infection, bladder injuries, ureteral injury, respiratory infections, paralytic ileus, and thrombophlebitis. Although vaginal delivery results in a statistically higher need for maternal re-hospitalization (p<0.001), we did not observe any statistical difference in maternal complications according to the type of delivery.

There are controversies surrounding cesarean delivery and neonatal morbidity rates [4, 12, 22]. Some authors associate elective cesarean section with a higher incidence of iatrogenic prematurity [4]. In our study, 74.63% of the patients underwent cesarean section without entering labor, and in 17.17%, the indication for cesarean section was at the patient‘s request. Despite these numbers, we did not observe a higher incidence of neonatal complications when we compared vaginal delivery with cesarean section. In contrast, we observed a higher incidence of intrapartum anoxia in those who had vaginal delivery. However, the number of vaginal deliveries was too small for us to draw any definite conclusions regarding intrapartum anoxia.

Pearson and Mackenzie [21] evaluated the incidence, indications, and complications of cesarean delivery during the second stage of labor over the last 30 years at 10-year intervals. They observed that newborns delivered by cesarean section during the second stage of labor had a lower Apgar score and lower umbilical cord blood pH than those delivered by cesarean section during the initial stages of labor. They authors did not observe a decrease in the rate of neonatal trauma when they compared cesarean section performed during the second stage of labor to that performed without labor or during the first stage of labor. In contrast, Visco et al. [23] found a higher incidence of transient tachypnea among patients who underwent cesarean section without labor.

There were no cases of maternal death in our study. Although the vast majority of births were by cesarean section, we cannot affirm that this type of delivery influences maternal mortality rates. There were 3 stillbirths and 4 newborn deaths. However, because the ultimate causes were not found, we cannot attribute these deaths to the type of delivery.

Among the limitations of the study are the fact that it is retrospective, that it relied on a structured questionnaire for data collection, and that there are few vaginal deliveries in private health services in Brazil. However, the large number of patients interviewed allowed us to characterize the deliveries performed in the private health service in our study, which can be extrapolated to other regions in Brazil.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we conclude that most deliveries in the private health service in our study were by cesarean section without labor and were performed by the patient‘s obstetrician. We did not find any serious maternal complications or increased neonatal morbidity rates to be directly associated with cesarean section.

Correspondence:

Prof. Edward Araujo Júnior, Ph.D.

Rua Belchior de Azevedo, 156 apto. 111 Torre Vitoria

São Paulo-SP

Brazil

CEP 05089-030

e-mail: araujojred@terra.com.br

Sources

1. Alexander, JM., Leveno, KJ., Rouse, DJ., et al. Comparison of maternal and infant outcomes from primary cesarean delivery during the second compared with first stage of labor. Obstet Gynecol, 2007, 109(4), p. 917–921.

2. Armson, BA. Is planned cesarean childbirth a safe alternative? CMAJ, 2007, 176(4), p. 475–476.

3. Barros, FC., Victora, CG., Barros, AJD., et al. The challenge of reducing neonatal mortality in middle-income countries: findings from three Brazilian birth cohorts in 1982, 1993, and 2004. Lancet, 2005, 365(9462), p. 847–854.

4. Boyle, A., Reddy, UM., Landy, HJ., et al. Primary cesarean delivery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol, 2013, 122(1), p. 33–40.

5. Cecatti, JG., Andreucci, CB., Cacheira, PS., et al. [Factors Associated with Cesarean Section in Primipara Women with One Previous Cesarean Section]. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet, 2000, 22(3), p. 175–179.

6. Declercq, E., Barger, M., Cabral, HJ., et al. Maternal outcomes associated with planned primary cesarean births compared with planned vaginal births. Obstet Gynecol, 2007, 109(3), p. 669–677.

7. Ecker, J. Elective cesarean delivery on maternal request. JAMA, 2013, 309(18), p. 1930–1936.

8. Fabri, HR., Murta, FE. [Delivery and Medical Attendance Types in Uberaba-MG]. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet, 1999, 21(2), p. 99–104.

9. Getahun, D., Oyelese, Y., Salihu, HM., Ananth, CV. Previous cesarean delivery and risks of placenta previa and placental abruption. Obstet Gynecol, 2006, 107(4), p. 771–778.

10. Gibbons, L., Belizán, JM., Lauer, JA., et al. Inequities in the use of cesarean section deliveries in the world. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2012, 206(4), p. 331.e1–19.

11. Hammad, IA., Chauhan, SP., Magann, EF., Abuhamad, AZ. Peripartum complications with cesarean delivery: a review of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network publications. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2014, 27(5), p. 463–474.

12. Hankins, GD., Clark, SM., Munn, MB. Cesarean section on request at 39 weeks: impact on shoulder dystocia, fetal trauma, neonatal encephalopathy, and intrauterine fetal demise. Semin Perinatol, 2006, 30(5), p. 276–287.

13. Levine, EM., Ghai, V., Barton, JJ., Strom, CM. Mode of delivery and risk of respiratory diseases in newborns. Obstet Gynecol, 2001, 97(3), p. 439–442.

14. Marshall, NE., Fu, R., Guise, JM. Impact of multiple cesarean deliveries on maternal morbidity: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2011, 205(3), p. 262.e1–8.

15. Martin, JA., Hamilton, BE., Ventura, SJ., et al. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep, 2012, 61(1), p. 1–71.

16. Moraes, MS., Goldenberg, P. [Cesarean sections: an epidemic profile]. Cad Saude Publica, 2001, 17(3), p. 509–519.

17. National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement vaginal birth after cesarean: new insights March 8–10, 2010. Semin Perinatol. 2010, 34(5), p. 351–365.

18. Oladapo, OT., Lamina, MA., Sule-Odu, AO. Maternal morbidity and mortality associated with elective Caesarean delivery at a university hospital in Nigeria. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol, 2007, 47(2), p. 110–114.

19. Oliveira, RR., Mělo, EC., Novaes, ES., et al. Factors associated to Caesarean delivery in public and private health care systems. Rev Esc Enferm USP, 2016, 50(5), p. 733–740.

20. Osava, RH., Silva, FM., Tuesta, EF., et al. Cesarean sections in a birth center. Rev Saude Pública, 2011, 45(6), p. 1036–1043.

21. Pearson, GA., Mackenzie, IZ. A cross-sectional study exploring the incidence of and indications for second-stage cesarean delivery over three decades. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2017 Jun 11. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12236. [Epub ahead of print]

22. Pergialiotis, V., Vlachos, DG., Rodolakis, A., et al. First versus second stage C/S maternal and neonatal morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2014, 175, p. 15–24.

23. Visco, AG., Viswanathan, M., Lohr, KN., et al. Cesarean delivery on maternal request: maternal and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol, 2006, 108(6), p. 1517–1529.

Labels

Paediatric gynaecology Gynaecology and obstetrics Reproduction medicine

Article was published inCzech Gynaecology

2018 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Medroxyprogesteron acetate use to block LH surge in oocyte donor stimulation

- Development of prenatal diagnostics of congenital heart defects, profit of standardized scanning planes

- Intravenous leiomyomatosis as a rare tumor of myometrium

- Various approaches of endometrial preparation for frozen-thawed embryo transfer

- Validation of a new tool for identification of barriers to cervical cancer prevention in Slovakia

- Vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation

- Woman´s subarachnoid hemmorage in pregnancy

- Non-Hodgkin´s B-lymphoma of the ovaries with an unfavourable prognosis – incidental finding during caesarean section

- Hysteroscopically assisted laparoscopic salpingostomy in the treatment of tubal pregnancy

- One-Step Nucleic Acid Amplification method – what is the future of sentinel lymph node management?

- Pregnancy in women with solid-organ transplants

- Antibiotic therapy in pregnancy

- Impact of cesarean section in a private health service in Brazil: indications and neonatal morbidity and mortality rates

- Czech Gynaecology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Various approaches of endometrial preparation for frozen-thawed embryo transfer

- Antibiotic therapy in pregnancy

- Vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation

- Medroxyprogesteron acetate use to block LH surge in oocyte donor stimulation

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career