-

Medical journals

- Career

Early postoperative complications after elective degenerative lumbar spine surgery in elderly patients

Authors: P. Snopko; B. Kolarovszki; R. Opšenák; R. Richterová; M. Benčo; M. Hanko

Authors‘ workplace: Clinic of Neurosurgery, Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Comenius University in Bratislava and Martin University Hospital, Slovakia 1

Published in: Cesk Slov Neurol N 2018; 81(4): 450-456

Category: Original Paper

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn2018450Overview

Objective:

Degenerative lumbar spine disease is an increasing problem nowadays, affecting more and more people, especially, the elderly population. The older age of patients is generally associated with a higher rate of postoperative complications.Patients and methods:

A retrospective analysis of patients aged 60 years or older who underwent the elective spine surgery at the Clinic of Neurosurgery at the University Hospital Martin from January 2015 to December 2016. Authors assessed the incidence of early postoperative complications after lumbar spine surgery in older patients and found a correlation between comorbidities, selected risk factors and the occurrence of postoperative complications.Results:

Overall, 107 patients were assessed (48 men and 59 women). The incidence of postoperative complications was 24.3%. The incidence of major complications was 9.4%, the incidence of minor complications was 17.8%. 7.5% of patients needed revision surgery. 83.2% of patients underwent decompressive surgery alone while, 16.8% of patients underwent spinal surgery with fusion. The rate of complications was higher in those patients who underwent surgery with instrumentation in comparison to the decompressive surgery alone (23.6 vs. 27.8%; p = 0.7561). There was a statistically significant association between the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and the incidence of complications (p = 0.0082). The length of a surgical procedure strongly affected the occurrence of postoperative complications (p = 0,001).Conclusion:

Almost one quarter of patients aged 60 years or older developed postoperative complications with the predominance of minor complications. The study showed an increasing rate of complications in patients who underwent a surgical procedure with instrumentation compared to patients with decompressive surgery only, but without statistical significance. We proved an association between the surgery length, the length of the hospital stay, the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and the presence of postoperative complications.Key words:

spine surgery – postoperative complications – degenerative spine – comorbiditiesIntroduction

It is well known that the number of elderly people is increasing, so there is also an associated increase of age-related diseases, such as degenerative changes in lumbar spine [1,2]. An aging population requires that surgeons must increasingly consider operative intervention in elderly patients. At the time of surgery indication, it is important to assess the risk of complications incidence, especially surgical ones, because when they occur, they usually lead to reoperation, prolonged hospitalisation and drug use, economic consequences and a compromised postoperative outcome and benefits [3,4]. Precise knowledge on postoperative complications is very important and valuable for a surgeon, as well as for a patient. If we want to perform degenerative lumbar spine surgery safely, it also requires understanding the factors that predict a successful outcome as well as the complications. The occurrence of postoperative complications in spine surgery varies widely in literature [5]. In this study, we assess the impact of risk factors (body mass index; BMI, the type of surgical procedure, the length of surgical procedure) and comorbidities on the occurrence of postoperative complications. In the planning of spine surgery, there are differences in indications among the neurosurgeons and orthopaedic surgeons, usually depending on the surgeon’s own experience. Surgery in older patients has its clear and proven postoperative benefits and a successful outcome when it is appropriately indicated, but there is a question of overtreatment [6]. Specific indications for procedures in pain-related surgery are generally lacking, therefore, in procedure selection, the characteristics of a patient and a disease may be outweighed by the individual preferences of a surgeon [7]. These choices are very important, especially in older patients, because greater invasiveness is usually associated with more complications [8,9]. Lots of trials showed an equal efficiency between decompression only and decompression with fusion. Preoperative risk assassment is crucial for successful outcomes after any spine surgery [10,11]. Many factors may contribute to the complications incidence [12,13]. Better information about postoperative complications and risk factors would help surgeons to estimate risks and benefits, and to make more individual decisions and indications [14 – 16].

Patients and methods

In this study, we assessed all patients aged 60 years or older who had undergone the surgery due to the degenerative lumbar spine disease in the period of 2 years (2015 – 2016). We included patients with any kind of degenerative lumbar spine disease – degenerative disc disease, lumbar spine stenosis, degenerative spondylolisthesis and lumbar spine segmental instability. The inclusion criteria were diagnosis and the patient’s age.

All patients received 2 g of cefazolin (600 mg of clindamycin, event.) 60 min before skin incision. Antibiotics were administered until 24 h postoperatively. Prolonged antibiotic microbial prophylaxis (48 h postoperatively) was administered, when the time of surgery exceeded 240 min.

Regarding deepvein thrombosis prophylaxis, graduated stockings, as well as low molecular weight heparin were used in all patients.

Transpedicular screw insertion was controlled by C-arm fluoroscopy (Phillips, Amster-dam, The Netherlands) during the surgery. Peroperative haemostasis was controlled by unipolar and bipolar coagulation, excessive bleeding was controlled by topical haemostatic agents (Spongostan, Gelaspon). Suction drains were used in almost all patients (except five patients after one-level discectomy or hemilaminectomy). Drains were placed over the laminectomy/ hemilaminectomy as close as possible to the thecal sac, negative vacuum pressure was applied immediately after the wound closure. Drains were removed between the 1st and 3rd postoperative day, depending on the amount of suction.

Each patient with diabetes mellitus (DM) on insulin therapy or oral antidiabetics un-derwent diabetologic preoperative examination with preoperative, peroperative and postoperative treatment recommendations. Glucose concentration was recorded in a 6-h glycemic profile before surgery. The use of oral antidiabetics (especially biguanides) was discontinued before surgery, glycemia was controlled with short acting insulin.Only patients with an adequate compensation of DM (glucose levels within 4.0–8.0 mmol/l range) underwent surgical procedure. Glycemic profile was examined postoperatively in all patients with DM, levelsof glycemia were controlled by standard insulin therapy, hyperglycemia was controlledby short acting insulin. Oral antidiabetics were restarted, when the patient has resumed adequate and regular oral intake.

We focused on the occurrence of in-hospital postoperative complications using a retrospective analysis. There was no specific consensus in previous articles regarding the definition of a postoperative complication in spine surgery. We used the most relevant scheme dividing postoperative complications into major (adverse events with permanent sequelae, usually requiring a reoperation) and minor (adverse perioperative events with a transient effect) [17]. We also assessed the mortality of patients and the necessity for further reoperation.

We conducted this study to determine an association between postoperative complications and patient’s comorbidities. We assessed all comorbidities from which patients, who underwent spine surgery, were suffering, and we separately evaluated the impact of comorbidities on the occurrence of postoperative complications using a statistical analysis.

The antropometric factors of our interest were BMI and gender. We analysed if the time of surgery and the type of surgical procedure (the level of invasiveness) had influenced the occurrence of postoperative complications. According to the level of invasiveness, we divided patients into two groups – decompression only and decompression with fusion. Decompression included any kind of discectomy, hemilaminectomy or laminectomy without fusion.

The results were assessed by descriptive statistics. Statistical significance of the results obtained was assessed by descriptive statistics, Student’s t-test and a Fisher’s test Data were assessed by GraphPad Software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Probability values of < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

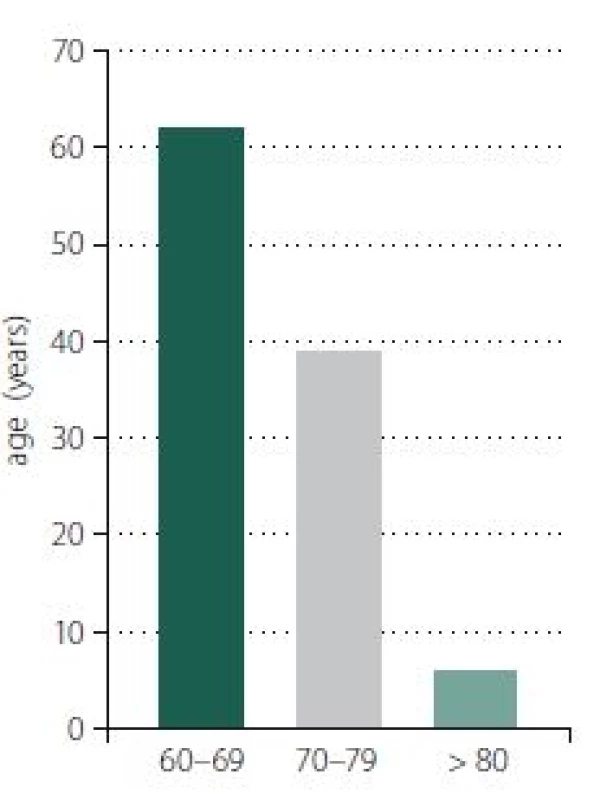

In the entire study, data from 107 patients aged 60 years or older were assessed (Fig. 1). The average age of included patients was 69.5 years. 48 patients (44.9%) were males, 59 patients (55.1%) were females. Among these patients, 72.9% had the diagnosis of spinal stenosis, 14.3% of patients had spondylolistesis, 65.4% had diagnosis of herniated or degenerative disc disease, 14.1% had segmental instability.

1. Patients divided according to age.

Obr. 1. Rozdelenie pacientov podľa veku.

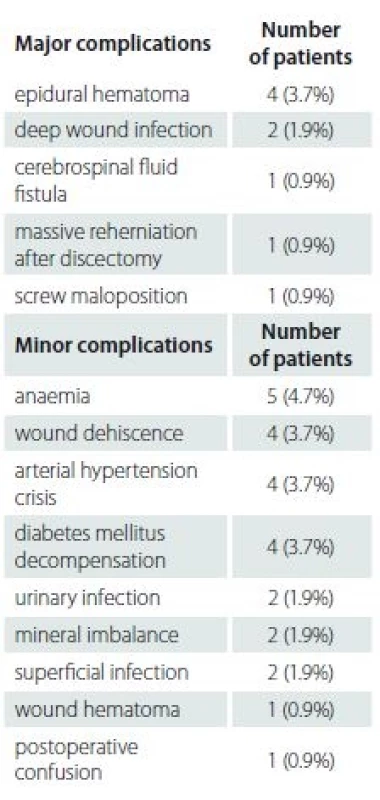

Postoperative complications were divided into 2 main groups – major and minor complications. Perioperative events leading to adverse sequelae, usually requiring a return to an operating room, were assessed as major complications. Other events, associated with transient sequelae, were deemed as minor. In this study cohort, we reported 9 major complications in 8 patients (7.4%) and 25 minor complications in 19 patients (17.8%). Overall, 26 patients (24.1%) had 34 complications (Tab. 1).

1. Major complications (9 complications/ 8 patients) and minor complications (25 complications/ 19 patients).

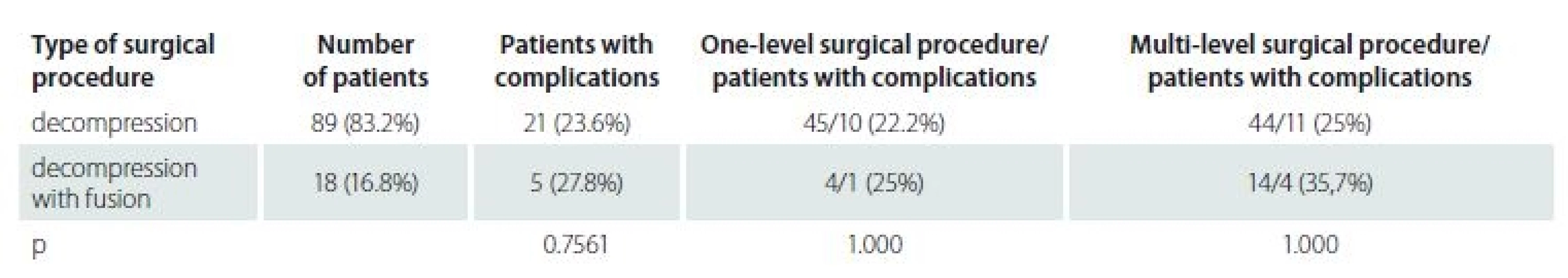

Out of the total cohort of 107 patients, 89 (83.2%) patients underwent only decompressive surgery. 21 (23.6%) patientsof this group had complications. 18 (16.8%)patients underwent surgery with instrumentation, 5 developed postoperative complications (27.8%). Patients, in whom a surgical procedure was performed with instrumentation were more likely to develop complications, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.7561).

We divided patients according to the level of invasiveness. Patients with a higher number of levels of surgical procedure developed more complications, but the difference was not statistically significant (Tab. 2).

2. Occurrence of postoperative complications according to the level of invasiveness.

Eight patients underwent revision surgery, 4 of them due to epidural hematoma, 1 due to cerebrospinal fluid leak, the next one due to the malposition of the transpedicular screw, another one due to the deep wound infection. The last patient underwent revision surgery due to postoperative massive dis creherniation. Major complications were strongly associated with reoperation. One patient with postoperative epidural hematoma was without the application of subfascialsuction drain.

We analysed an association between selected antropometric parameters (BMI, gender, age) and the occurrence of complications. The mean age of patients with complications was 69.4 years, and without complications was 70.2 years (p = 0.5309). BMI was higher in patients with complications (29.2 vs. 28.9), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.8941). The presence of complications was higher in a cohort of female patients than in male patients (28.9 vs. 18.8%; p = 0.2630).

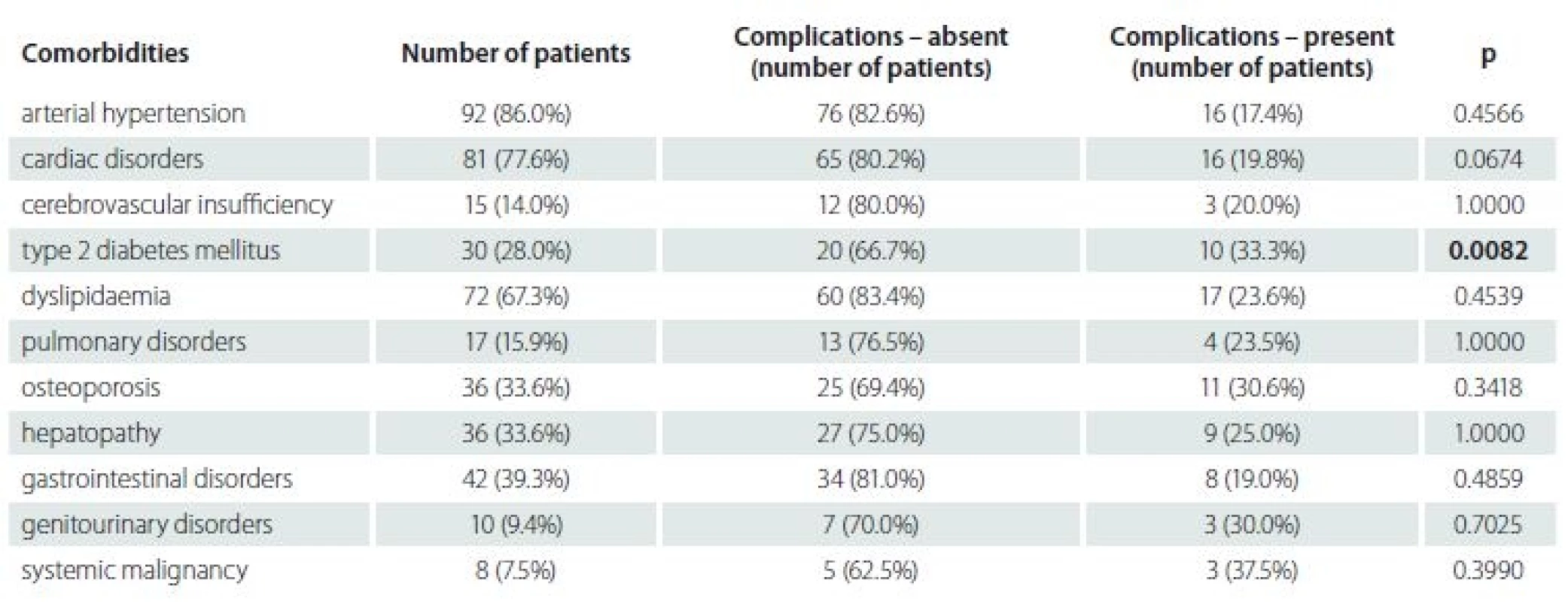

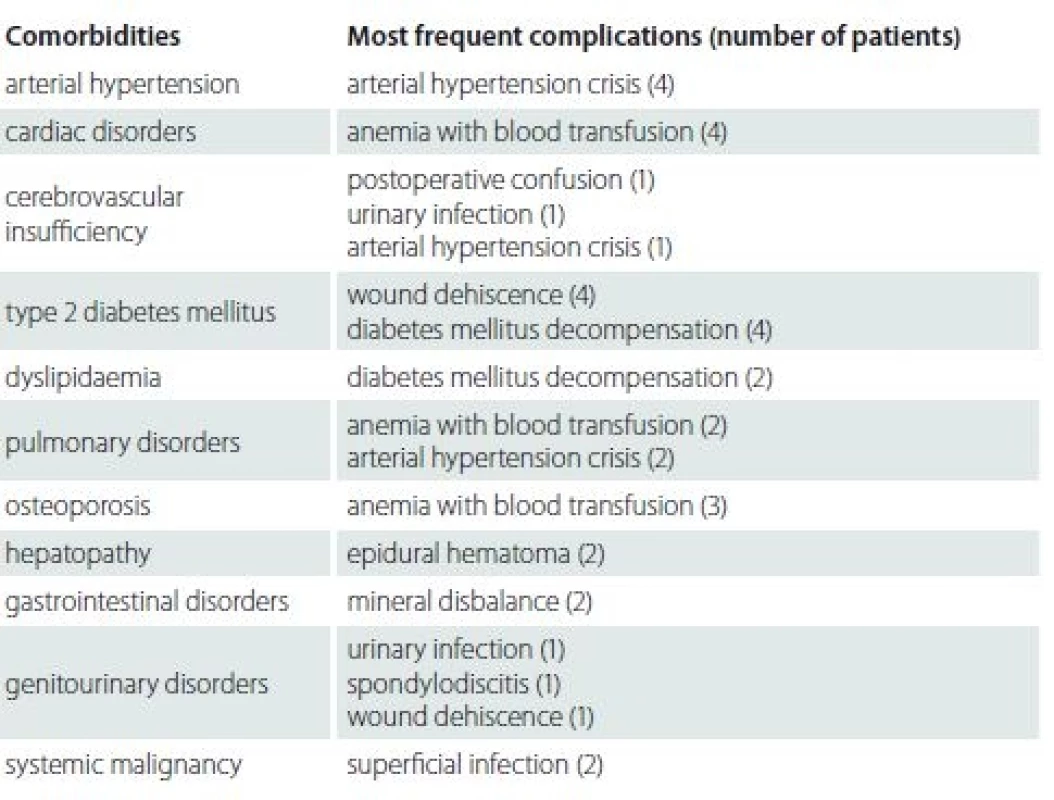

Comorbidities such as arterial hypertension, osteoporosis, DM and other systemic diseases were assessed to determine any correlation with postoperative complications. The comorbidities that mostly occurred were evaluated separately. The most common comorbidity was arterial hypertension (86% of patients). We found a statistically significant association between the presence of type 2 DM and the occurrence of postoperative complications (Tab. 3, 4). Ten patients with type 2 DM had postoperative complications, 12 patients were on oral antidiabetics, 8 patients were on insulin therapy. 33.3% of patients on oral antidiabetics and 75% of patients on insulin therapy had postoperative complications. Complications in patients with type 2 DM were wound dehiscence (4 patients), DM decompensation (4 patients), urinary infection (1 patient) and postoperative anaemia with blood transfusion (1 patient).

3. Comorbidities – correlation between presence of comorbidities and the occurrence of complications.

4. Most frequent postoperative complications according to the comorbidities.

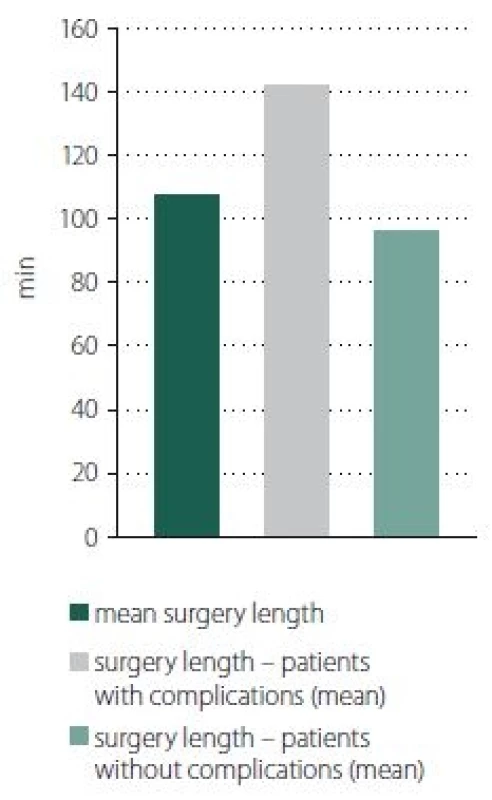

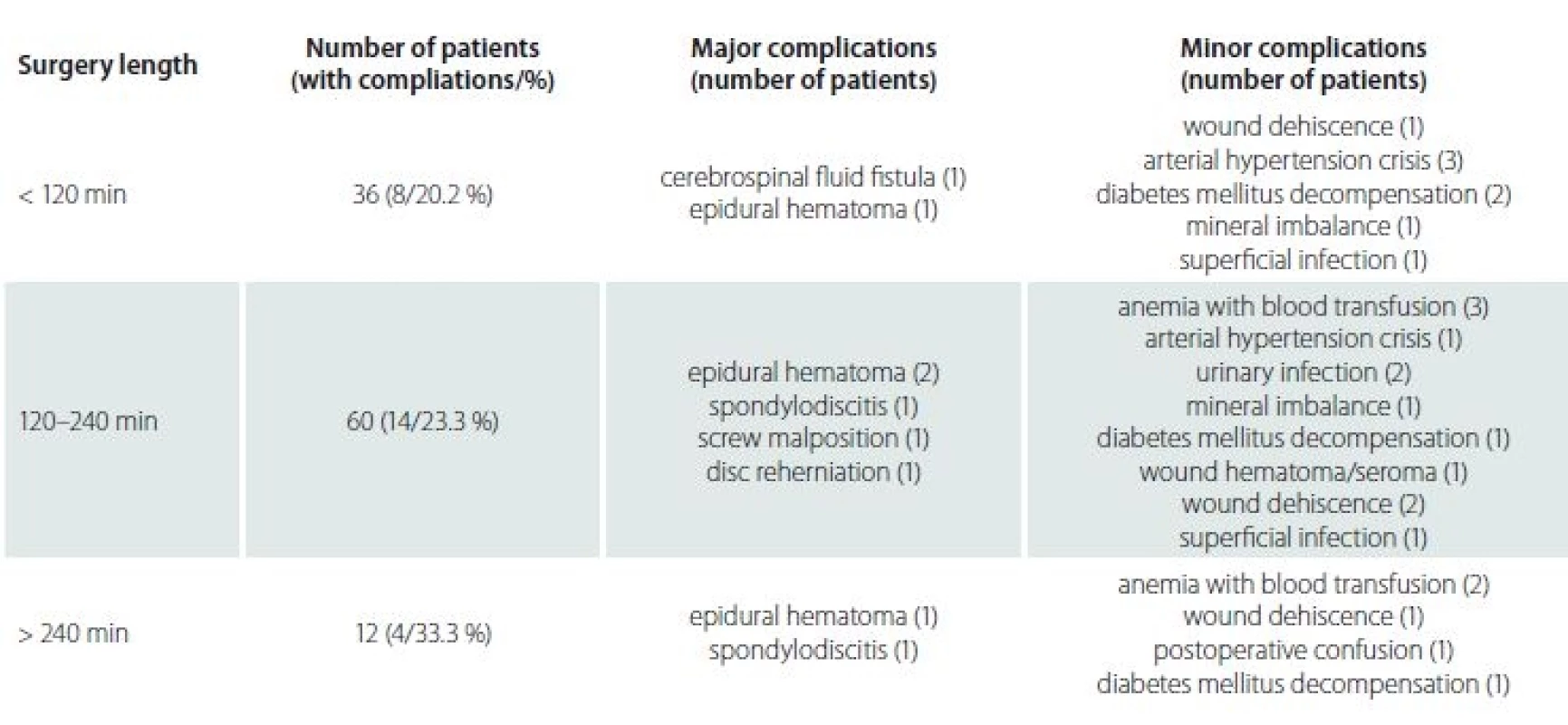

The average time of surgical procedure was 107.3 min. Patients with postoperative complications had longer surgery time (142.0 vs. 96.2 min), and this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). We can consider the longer time of surgery as an important risk factor of postoperative complications. Postoperative complications were also divided according to the time of surgery (Tab. 5).

2. Surgery length – comparison between patients with and without complications.

Obr. 2. Dĺžka operácie – porovnanie medzi pacientmi s komplikáciami a bez komplikácií.

5. Occurence of postoperative complications according to the surgery length.

The length of stay in hospital ranged from 7 to 51 days. The occurrence of complications strongly affected the duration of hospitalisation. An average hospital stay in patients without complications was 9 days, whereas in patients with complications, the average hospital stay extended to 14 days (p < 0.001). On the basis of these results, we can also predict increased medical costs of the hospitalisation of patients with complications after spine surgery.

Discussion

Nowadays, postoperative complications of spine surgery in older patients represent an important object of study because of the improvement of health care services and growing medical costs [18,19]. Complications after surgery are also an important stress factor to patients themselves, patients’ families, as well as for surgeons [20]. This disease usually affects the elderly part of the population, therefore, the surgeons who evaluate these patients must carefully consider the potential benefit and possible risk factors, such as substantial comorbidities. When the surgical treatment of degenerative lumbar spine is successful, it can produce a remarkable improvement in function, ambulation and activities of daily living.

The rate of postoperative complications in spine surgery widely differs in literature. In our study, we focussed on major and minor complications. Our results confirmed that spine surgery in older patients carries relatively high risk of postoperative complications. This study revealed an overall complication incidence of 24.1% , which is similar to previous studies [10 – 12,20,21]. The overall incidence of major complications was 7.4%, the incidence of minor complications was 17.8%. Cassinelli et al revealed the incidence of 33.1%, with the predominance of minor complications [21], Button et al reported the complication incidence of 30% [22]. Findings by Deyo et al demonstrated an 18% complications rate in a similar group of patients [6]. The most common major complication requiring revision surgery was epidural hematoma. The most common minor complications were DM decompensation and wound dehiscence.

In this study, the rate of postoperative complications was higher in patients who underwent surgery with instrumentation than in patients with decompression only (27.8 vs. 23.6%), but without statistical significance. More complex procedures were associated with the higher rate of complications, but in general, the evidence for better efficacy of more complex procedures for degenerative lumbar spine disease is lacking [23]. It is not surprising that more complex surgery is associated with a higher complications risk because fusion usually requires longer surgery time, more extensive dissection and placement of implants [24]. A few studies proved equivalent efficacy for decompression alone vs. decompression and fusion (with the absence of spondylolisthesis) [25]. These results revealed that it is very important for a surgeon to assess whether decompression alone is sufficient enough, whether stabilising structures (facet joints, interspinous ligaments) should be preserved, when the fusion is indicated and to what extent instrumentation is needed [26].

This study showed a statistically significant correlation between the time of surgery and the occurrence of complications. This result is also associated with the type of surgical procedure, because the time of surgical procedures with fusion was longer than the time of decompressive surgery only. There was a statistically significant difference between the length of hospital stay in patients with and without complications (9 vs. 14 days). These results can predict economic importance of the occurrence of postoperative complications, because a longer hospital stay may significantly increase medical costs of hospitalisation.

There were no statistically significant differences in gender distribution (female vs. male – 28.9 vs. 18.8%) and BMI (29.2 vs. 28.9) among patients who developed complications and those who did not. BMI was higher in patients with complications, but the difference was not statistically significant. Other trials showed various results, a few studies showed an association between obesity and complications, but other studies failed to prove this correlation [26 – 28].

An association between comorbidities and complications in spine surgery is not conclusively demonstrated in literature. Other previous studies used various types of comorbidity indexes to evaluate an impact on the occurrence of complications. In this study, we evaluated the impact of comorbidities separately and despite a different type of evaluation, our results were similar to other previous trials [8,29 – 34]. We divided comorbidities into 11 groups according to their incidence and importance. This study revealed an association between the presence of the type 2 DM and the increased risk of complications. This result showed a statistical significance (p < 0.05) as well. Management of glycemia before and during surgery is very important, especially in diabetic patients, because of negative effects of surgical stress and anaesthesia on blood glucose levels. Nowadays, there is no evidence-based guideline indicating when to cancel surgery due to hyperglycaemia. Elective surgery should not be performed in patients with a compromised metabolic state. Careful glycaemic management in patients with preoperative diabetologic examination with given recommendations may reduce morbidity and mortality and improve surgical outcomes. In our study, instead of adequate compensation of DM preoperatively and postoperatively, type 2 DM was a statistically significant risk factor of postoperative complications [35,36].

Two of the patients developed spondylodiscitis after surgery, despite of standard preoperative and postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis and aseptic rules. Both patients underwent surgical procedure with instrumentation. One of the patients was treated conservatively, the other one was treated surgically. Our results were similar to other studies showing the incidence of postoperative deep wound infection of 0.21 – 3.6% [37]. A study by Hey et al reported a reduced risk of postoperative surgical site infection using prophylactic intraoperative local vancomycin powder in patients undergoing instrumented spine surgery [38].

Incidence of postoperative epidural hematoma is a serious complication. In our study, 4 patients had a symptomatic postoperative epidural hematoma leading to reoperation. Only 5 patients were without applications of subfascial suction drains. One patient from this group had postoperative epidural hematoma. Use of the suction drain facilitates the removal of an intrawound hematoma, however, several studies have reported that the suction drain does not prevent the development of such a complication. Study by Dong Ki Ahn et al showed, that suction drains functioned well before a coagulation nidus was formed. Drains should be placed as close as possible to the thecal sac, a vacuum should be connected before the clotting of extravascular blood. It is recommended not to use any materials, that activate platelet and facilitate coagulation of extravascular blood to prevent dysfunction of suction drains, but the type of prevention depends mainly on a surgeon‘s experience. Drains should be removed between the 1st and the 3rd day after surgery. Prolonged use of drains is considered as a risk factor of postoperative surgical site infections [39,40].

Complications incidence in spine surgery widely varies and may be influenced by many factors. Almost one quarter of elderly patients developed postoperative complications with the predominance of minor complications. On the basis of this study, we proved the correlation between the surgery length, the length of hospital stay, the presence of the type 2 DM and the incidence of postoperative complications. We equally proved an increasing rate of complications in those elderly patients who underwent surgical procedure with instrumentation than in the patients with decompressive surgery only. Spinal surgery in elderly patients carries a relatively high risk of postoperative complications, but more individual decisions at the time of surgery indication, the knowledge about risk factors leading to the higher complications rate and better information about patients may lead to serious improvement in healthcare services, better postoperative outcomes and a decrease in medical costs.

This work was supported by project The application of PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication System) in the research and development, ITMS 26210120004.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Accepted for review: 9. 1. 2018

Accepted for print: 28. 5. 2018

doc. MUDr. Branislav Kolarovszki, PhD.

Clinic of Neurosurgery

Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin

Comenius University in Bratislava

and Martin University Hospital

Kollárova 2

036 59 Martin

Slovakia

e-mail: kolarovszki@jfmed.uniba.sk

Sources

1. Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans Update 2006: Key Indicators of Well--Being. [online]. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office 2006. Available from URL: https:/ / agingstats.gov/ docs/ PastReports/ 2006/ OA2006.pdf.

2. Rudinsky B, Kolejak K. Degeneratívne ochorenie driekovej chrbtice – možnosti chirurgickej liečby. Neurol praxi 2008; 9(3): 134 – 139.

3. Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL et al. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalisation, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1999; 20(11): 725 – 730. doi: 10.1086/ 501572.

4. Calderone RR, Garland DE, Capen DA et al. Cost of medical care for postoperative spinal infections. Orthop Clin North Am 1996; 27(1): 171 – 182.

5. Campbell PG, Yadla S, Nasser R et al. Patient comorbidity score predicting the incidence of perioperative complications: assessing the impact of comorbidities on complications in spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine 2012; 16(1): 37 – 43. doi: 10.3171/ 2011.9.SPINE11283.

6. Deyo RA, Nachemson A, Mirza SK. Spinal-fusion surgery – the case for restraint. N Engl J Med 2004; 350(7): 722 – 726. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMsb031771.

7. Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson PR et al. United States trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992 – 2003. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006; 31(23): 2707 – 2714. doi: 10.1097/ 01.brs.0000248132.15231.fe.

8. Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH et al. Trends, complications, and costs for hospital admission and surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017; 42(22): 1737 – 1743. doi: 10.1097/ BRS.0000000000002207.

9. DeWald CJ, Stanley T. Instrumentation-related complications of multilevel fusions for adult spinal deformity patients over age 65: surgical considerations and treatment options in patients with poor bone quality. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006; 31 (19 Suppl): 144 – 151. doi: 10.1097/ 01.brs.0000236893.65878.39.

10. Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI et al. Trends, major medical complications, and charges associated with surgery for lumbar spine stenosis in older adults. JAMA 2010; 303(13): 1259 – 1265. doi: 10.1001/ jama.2010.338.

11. Mirza SK, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ et al. Development of an index to characterize the “invasiveness” of spine surgery: validation by comparison to blood loss and operative time. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008; 33(24): 2651 – 2661. doi: 10.1097/ BRS.0b013e31818dad07.

12. Li G, Patil CG, Lad SP,et al. Effects of age and comorbidities on complication rates and adverse outcomes after lumbar laminectomy in elderly patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008; 33(11): 1250 – 1255. doi: 10.1097/ BRS.0b013e3181714a44.

13. Hrabalek L, Adamus M, Wanek T et al. Surgical complications of the anterior approach to the L5/ S1 intervertebral disc. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2012; 156(4): 354 – 358. doi: 10.5507/ bp.2011.064.

14. Grob D, Humke T, Dvorak J. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: decompression with and without arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77(7): 1036 – 1041.

15. Lebude B, Yadla S, Albert T et al. Defining “complications” in spine surgery: neurosurgery and orthopaedic spine surgeons‘ survey. J Spinal Disord Tech 2010; 23(8): 493 – 500. doi: 10.1097/ BSD.0b013e3181c11f89.

16. Durny P. Možnosti miniinvazívnej chirurgickej liečby pacientov s degeneratívnym ochorením driekovej chrbtice. Slov Chir 2014; 11(2): 48 – 52.

17. Sebesta P, Stulík J, Vyskocil T et al. Cauda equine syndrome after elective lumbar spine surgery. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 2009; 76(6): 505 – 508.

18. Micankova Adamova B, Vohanka S. Kvantifikace postižení u pacientů s lumbální spinální stenózou. Cesk Slov Neurol N 2013; 76/ 109(5): 570 – 574.

19. Micankova Adamová B, Hnojcikova M, Vohanka S et al. Oswestry dotazník, verze 2.1a - výsledky u pacientů s lumbální spinální stenózou, srovnání se starší verzí dotazníku. Cesk Slov Neurol N 2012; 75/ 108(4): 460 – 467.

20. Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Lew RA. Lumbar laminectomy alone with instrumented or non-instrumented arthrodesis in degenerative lumbar spine stenosis: patient selection, costs, and surgical outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997; 22(10): 1123 – 1131.

21. Cassinelli EH, Eubanks J, Vogt M et al. Risk factors for development of perioperative complications in elderly patients undergoing lumbar decompression and arthrodesis for spina stenosis: an analysis of 166 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007; 32(2): 230 – 235.

22. Button G, Gupta M, Barrett C et al. Three - to six-year follow-up of stand-alone BAK cages implanted by a single surgeon. Spine J 2005; 5(2): 155 – 160.

23. Ciol MA, Deyo RA, Howell E et al. An assessment of surgery for spinal stenosis: time trends, geographic variations, complications, and reoperations. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996; 44(3): 285 – 290.

24. Grob D, Humke T, Dvorak J. Degenerative lumbar spine stenosis: decompression with and without arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77(7): 1036 – 1041.

25. Cho KJ, Suk SI, Park SR et al. Complications in posterior fusion and instrumentation for degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007; 32(20): 2232 – 2237. doi: 10.1097/ BRS.0b013e31814b2d3c.

26. Patel N, Bagan B, Vadera S et al. Obesity and spine surgery: relation to perioperative complications. J Neurosurg Spine 2007; 6(4): 291 – 297. doi: 10.3171/ spi.2007.6.4.1.

27. Yadla S, Malone J, Campbell PG et al. Obesity and spine surgery: reassessment based on a prospective evaluation of perioperative complications in elective degenerative thoracolumbar procedures. Spine J 2010; 10(7): 581 – 587. doi: 10.1016/ j.spinee.2010.03.001.

28. Yagi M, Patel R, Boachie-Adjei O. Complications and unfavourable clinical outcomes in obese and overweight patients treated for adult lumbar or thoracolumbar scoliosis with combined anterior/ posterior surgery. J Spinal Disord Tech 2015; 28(6): E368 – E376. doi: 10.1097/ BSD.0b013e3182999526.

29. Li G, Patil CG, Lad SP et al. Effects of age and comorbidities on complication rates and adverse outcomes after lumbar laminectomy in elderly patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008; 33(11): 1250 – 1255. doi: 10.1097/ BRS.0b013e3181714a44.

30. Benz RJ, Ibrahim ZG, Afshar P et al. Predicting complications in elderly patients undergoing lumbar decompression. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; 384 : 116 – 121.

31. Glassman SD, Alegre G, Carreon L et al. Perioperative complications of lumbar instrumentation and fusion in patients with diabetes mellitus. Spine J 2003, 3(6): 496 – 501.

32. Okuda S, Oda T, Miyauchi A et al. Surgical outcome of posterior lumbar interbody fusion in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88 : 2714 – 2720. doi: 10.2106/ JBJS.F.00186.

33. Carreon LY, Puno RM, Dimar JR 2nd et al. Perioperative complications of posterior lumbar decompression and arthrodesis in older adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-A(11): 2089 – 2092.

34. Browne JA, Cook C, Pietrobon R et al. Diabetes and early postoperative outcomes following lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007; 32 : 2214 – 2219. doi: 10.1097/ BRS.0b013e31814b1bc0.

35. Guzman JZ, Iatridis JC, Skovrlj B et al. Outcomes and complications of diabetes mellitus on patients undergoing degenerative lumbar spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014; 39(19): 1596 – 1604. doi: 10.1097/ BRS.0000000000000482.

36. Epstein NE. Predominantly negative impact of diabetes on spinal surgery: a review and recommendation for better preoperative screening. Surg Neurol Int 2017; 8 : 107. doi: 10.4103/ sni.sni_101_17.

37. Smith JS, Shaffrey CI, Sansur CA et al. Rates of infection after spine surgery based on 108,419 procedures. Spine 2011; 36 : 556 – 563. doi: 10.1097/ BRS.0b013e3181eadd41.

38. Hey HW, Thiam DW, Koh ZS et al. Is intraoperative local vancomycin powder the answer to surgical site infections in spine surgery? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017; 42(4): 267 – 274. doi: 10.1097/ BRS.0000000000001710.

39. Ahn DK, Kim JH, Chang BK et al. Can we prevent a postoperative spinal epidural hematoma by using larger diameter suction drains? Clin Orthop Surg 2016; 8(1): 78 – 83. doi: 10.4055/ cios.2016.8.1.78.

40. Rao BR, Vasquez G, Harrop J et al. Risk factors for surgical site infections following spinal fusion procedures: a case-control study. Clin Inf Dis 2011; 53(7): 686 – 692. doi: 10.1093/ cid/ cir506.

Labels

Paediatric neurology Neurosurgery Neurology

Article was published inCzech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

2018 Issue 4-

All articles in this issue

- Detection of unstable carotid plaque in ischemic stroke prevention

- Aggressive treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage with lowering of blood pressure and indication of surgery - YES

- Aggressive treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage with lowering of blood pressure and indication of surgery - NO

- Aggressive treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage with lowering of blood pressure and indication of surgery - COMMENT

- Treatment targeted for B lymphocytes – significant progress in the treatment of multiple sclerosis

- Possibilities of regulation of neuroimmune and neuroendocrine processes using physiotherapy

- Parietal atrophy score on magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in normally aging people

- Imaging of peripheral nerves using diffusion tensor imaging and MR tractography

- The differences in clinical, radiological and treatment modalities of cervical intramedullary arachnoid cysts and cervical syringomyelia – report of 12 cases

- The relationship between tinnitus intensity and the degree of sensorineural hearing loss from the aspect of contribution of hyperbaric oxygen therapy

- Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in carotid endarterectomies

- A comparison of efficacy of subcutaneous interferon β-1a 44 μg, dimethyl fumarate and fingolimod in the real-life clinical practise – a multicenter observational study

- A set of pictures with the opposite difficulty of naming

- Pharyngo-cervico-brachial variant of Guillain-Barré syndroma

- Bilateral abducens nerve palsy after head and cervical spinal injury

- Late-onset Huntington’s disease – an overlooked diagnosis

- Early postoperative complications after elective degenerative lumbar spine surgery in elderly patients

- Orolingual bradykinin angioedema after tissue plasminogen activator in acute stroke – treatment with or without C1-esterase inhibitor

- Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in carotid endarterectomies

- Bilateral abducens nerve palsy after head and cervical spinal injury

- Imaging of peripheral nerves using diffusion tensor imaging and MR tractography

- Late-onset Huntington’s disease – an overlooked diagnosis

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career