-

Medical journals

- Career

Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Metastases of Adenocarcinoma as a Dominant Clinical Manifestation of Malignancy of Unknown Origin – a Case Report

Authors: Bartoš Vladimír 1; Hamarová Kamila 2

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Pathology, Faculty Hospital with polyclinic Žilina, Slovakia 1; Department of Surgery, Faculty Hospital with polyclinic Žilina, Slovakia 2

Published in: Klin Onkol 2018; 31(2): 143-147

Category: Case Report

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amko2018143Overview

Background:

Cutaneous metastases occur in 0.6–10.4% of all patients with underlying malignancy. Among them, the site of origin remains unknown in 4.4–14.5% of all cases.Case:

The authors describe a 68-year-old man with widespread skin and soft tissue metastases appearing as the first and dominant clinical manifestation of oncologic disease. Physical examination and CT scans revealed multiple cutaneous and subcutaneous tumor nodules arising in the neck, chest, abdomen, lumbar region and right forearm, as well as in the gluteal and iliacus muscles and in the proximal part of the left thigh. Light microscopy confirmed a metastasis of adenocarcinoma exhibiting a tubuloglandular pattern and a slight mucin production. It was immunoreactive for cytokeratin 7 and carcinoembryonic antigen and negative for cytokeratin 20, CDX-2, TTF-1 and prostatic specific antigen. Based upon the histomorphology and immunophenotype, the pathologist suggested a primary tumor in the stomach or biliopancreatic tract. However, further clinical workup did not clearly identify a primary lesion.Conclusion:

Determining the origin of cutaneous metastases might be a challenging issue for both clinicians and pathologists. The case we describe is uncommon because widespread skin and subcutaneous metastases appeared as the first and dominant clinical sign of adenocarcinoma, the origin of which has not been established. This unusual tumor behavior may suggest that a spreading and colonization of metastatic cancer cells in the skin and soft tissue may be a specific biologic process.Key words:

skin metastases – malignancy of unknown origin – adenocarcinomaIntroduction

Cutaneous metastases occur in 0.6 – 10.4% of all patients with underlying malignant neoplasm [1–3]. However, an accurate evaluation of the prevalence is difficult, because it requires a long follow-up period, which is not possible in many oncologic patients. In theory, any malignant tumor can spread to the skin, but it is quite a rare finding in a routine clinical practice [4,5]. Grossly, the skin metastases do not have a uniformly characteristic appearance, which may vary depending on the histologic type and location of originating malignancy [1,4–7]. They usually manifest as a firm, painless and some-times ulcerated cutaneous or subcutan-eous nodule (s) of various size and color [4,5]. However, the clinical present-ation may be highly variable and can often mimic other nosologic entities [4–9], leading to incorrect initial treat-ment and management. Most cutaneous metastases (73–88%) are found in patients with a known primary origin [3,6]. Occasionally, this may be also the first clinical manifestation of an occult primary malignancy [3,6,9,10]. Such cases comprise approximately 12–26.8% of all individuals with cutaneous metastases [3,6]. In some instances, the site of origin remains uncertain despite extensive clinical workup [3,6,7,11]. These cases represent a substantial diagnostic challenge for clinicians and pathologists. In the Czechoslovak medical literature, a few case reports dealing with skin metastases [8–10,12,13] have been published so far. Herein, we describe an additional new case of a patient with multiple cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases of adenocarcinoma as a do-minant clinical manifestation of malignancy, the origin of which has remained unknown.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old man (casus socialis) was admitted (September, 2016) to the Neurology Department for intense back pain in the lumbosacral region, irradiating to the left lower limb. Clinical anamnesis revealed a history of previously treated chronic duodenal ulcer and pulmonary tuberculosis, as well as chronic ethylismus and nicotinismus. No oncologic disease was known until that time. On initial physical examination, multiple cutaneous and subcutaneous nodosities of various size were visible in the neck, chest, abdominal wall, lumbar region and in the right forearm. The patient claimed the lesions have been present for the last 3–4 months and grew progressively. They were painless with a slightly brown-reddish color. At the first glance, they appeared like inflamed atheromas. The size of the lesions varied from about 1–8 cm in the largest diameter. The biggest one (7 × 7 × 5 cm) arose in the right lumbar region. It was fixed by touch with a livid surface, surrounded by erythematous skin. On computed tomography (CT), the lesion was oval, well demarcated and located in the paravertebral subcutaneous soft tissue in the vicinity of L3. Based on CT scan findings and locality, the clinical impression was a neurofibroma. With respect to pronounced symptomatology and unclear etiology of disease, a bi-opsy was indicated. The presumptive clinical diagnoses were as follows: subcutaneous atheromas or abscesses, multiple tumor metastases of unknown origin or secondary tbc infiltrates (as the patient suffered from lung tuberculosis in the past). A probatory biopsy of the lesion arising in the right lumbar region was done, and the sample was sent for histopathology.

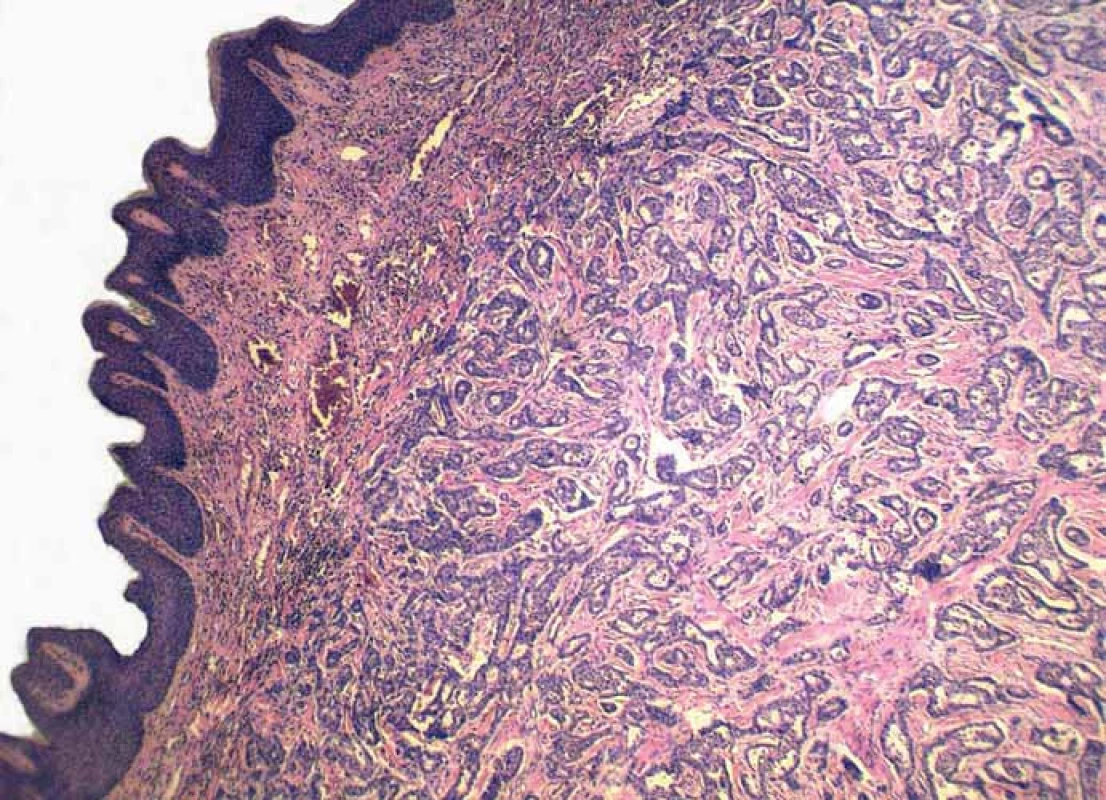

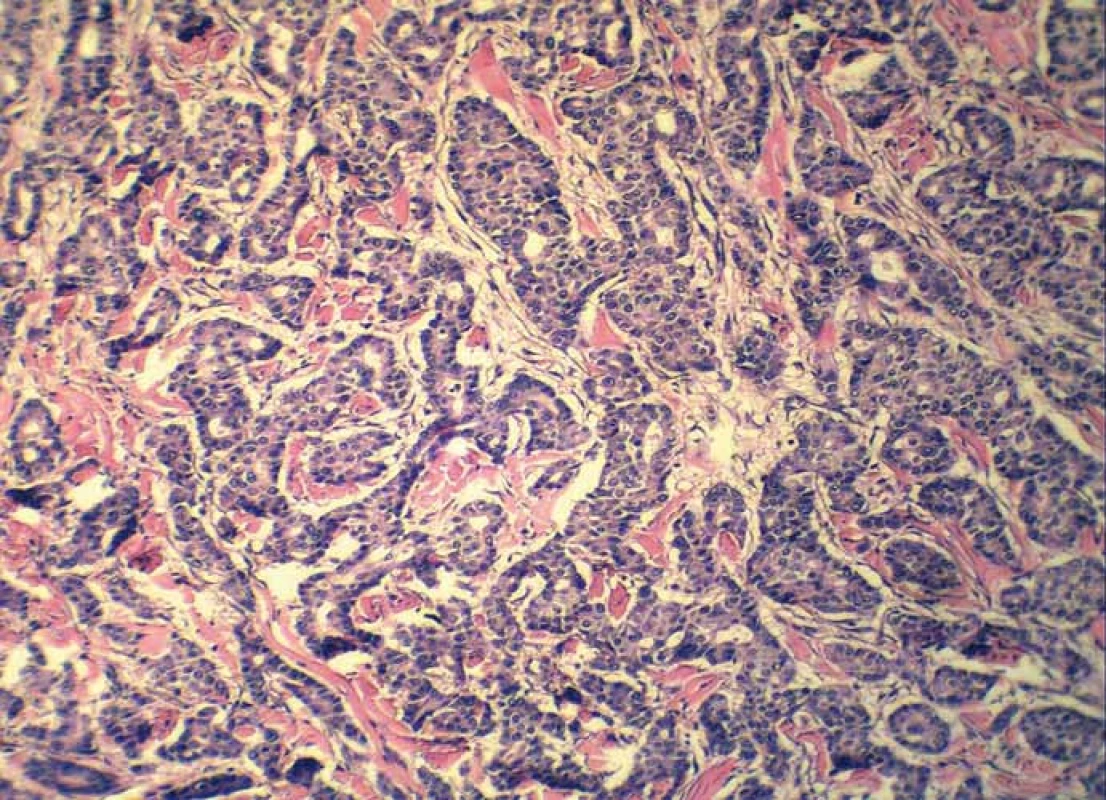

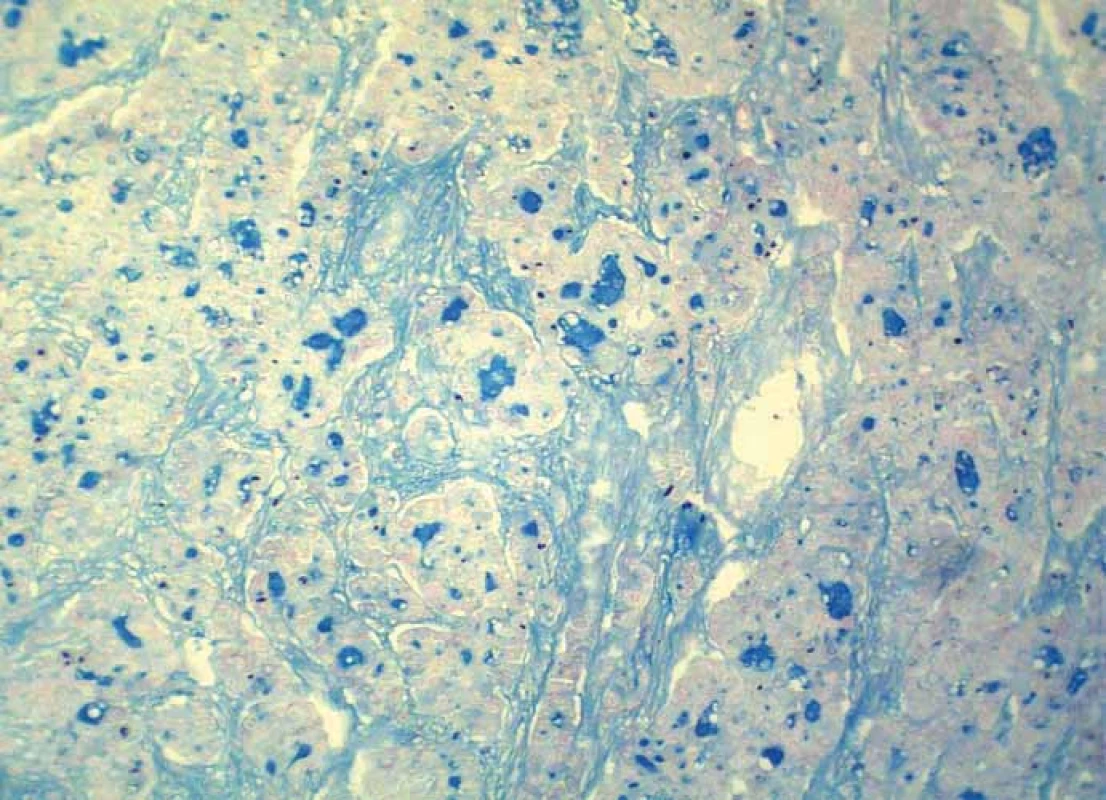

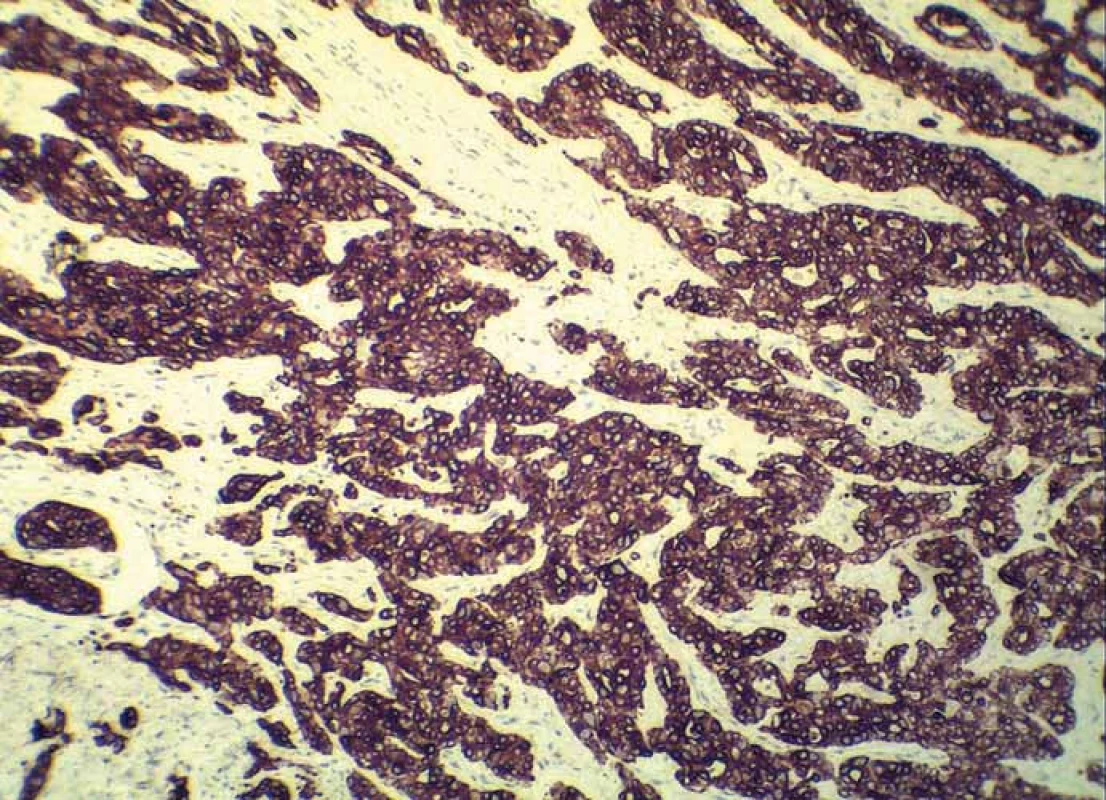

Grossly, the resection specimen consisted of the skin and subcutis with a visible superficial „bulge“ covered by intact epidermis. Longitudinal section revealed a well-circumscribed white-yellowish tumor mass measuring 42 mm (Fig. 1). Light microscopy confirmed a metastatic adenocarcinoma exhibiting a tubuloglandular microarchitecture (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). The tumor was centered in the dermis and subcutis without an epidermal involvement. There was a typical narrow zone of unaffected papillary dermis separating the tumor structures from the epidermis (so-called grenz zone). Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells were strongly reactive for cytokeratin 7 (Fig. 4) and carcinoembryonic antigen. The other markers we investigated (i.e. cytokeratin 20, CDX-2, TTF-1 and prostatic specific antigen) were negative. There was a slight intracellular and intraluminous mucin production (Fig. 5). The origin of adenocarcinoma was not possible to define, but based upon the histomorphology and imunophenotype, the pathologist suggested a primary in the stomach or biliopancreatic tract.

1. Resection specimen with a visible large tumor mass (post fi xation in formalin).

2. Metastatic infiltration of the dermis, while the epidermis is intact (hematoxylin and eosin, magnification 40×).

3. Detail on tubuloglandular microarchitecture of adenocarcinoma (hematoxylin and eosin, magnification 200×).

4. Intraluminous mucin production within tumor tissue (alcian blue, magnification 200×).

5. Strong immunoreactivity of adenocarcinoma for cytokeratin 7 (clone OV-TL 12/30, Dako, magnification 200×).

Subsequently, the patient underwent further clinical and imaging examinations. New CT scans showed other tumor lesions in the skin and underlying soft tissues. One of the largest one was found in the left gluteal muscle, it measured 7 × 2.6 cm and began to erode the iliac crest. The other lesions were present in the left iliac muscle, around inferior ramus of the pubic bone and in the proximal part of the left thigh, accompanied by destruction of the edge of femur. Probably these tumor masses resulted in lumbosacral pain, irradiating to the lower extremity. In both lungs, there were emphysema and post-inflammatory fibroadhesive changes with sporadic calcifications. In addition, two subpleural nodules with a diameter of 9 mm and 8 mm were visible in the right and left lung, resp. The liver, gallbladder, extrahepatic biliary ducts, stomach, spleen and adrenals were without noticeable tumor deposits. In the left kidney, a solitary hyperdense nodule (18 mm in diameter) was found. The posterior wall of urinary bladder was thickened and exhibited a superficial tumor mass (up to 3.6 cm), which has propagated into the lumen. Transurethral resection of the bladder was performed and histopathology showed a typical „high-grade“ non-invasive papillary urothelial carcinoma. Thus, this tumor did not correspond to metastases. Endoscopy of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum did not reveal persuasive tumor changes. Nevertheless, biopsy samples were obtained from these organs for histopathology. A light microscopy confirmed a mild antral gastritis with no intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia.

During a stay in the hospital, cuta-neous and subcutaneous tumor masses progressed and some became ulcer-ated. Systemic chemotherapy (CDDP + gemcitabine) was started. However, the situation was complicated by an accidental fall to the ground with a subtrochanteric fracture of the left femur. Since then, the patient’s health condition rapidly worsened and he died a few days after initiation of the first cycle of chemotherapy. As the clinical workup did not clearly explore a primary tumor, it was classified as generalized metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin. Autopsy was not performed.

Discussion

Cutaneous metastases from visceral malignancies are important challenge in clinicopathologic practice for many reasons. Because of their variable clinical appearance and manifestation, frequent delays and failure in correct diagnosis do occur. This mainly happens in a situation when skin metastasis is the first apparent symptom of clinically silent visceral cancer. Even after exploring a biopsy-proven diagnosis, a wide spectrum of various internal malignancies come into consideration. A disclosure of primary lesion is often problematic and requires a comprehensive differential diagnostic approach. The relative frequencies of metastatic skin disease tend to correlate with the frequency of the different types of primary cancer in each gender [4,5]. Thus, the most common primary site of cutaneous metastases is the breast cancer in females and the lung and colonic carcinomas in males [3,4,6,7]. However, despite careful clinical and laboratory exams, it is not possible to identify a primary tumor in certain individuals. Such cases account for 4.4–14.5% of all patients with cutaneous metastases [3,6,7,11]. Our present case may be included into that category, as we were not able to establish clearly the origin of malignancy. In particular, an interesting feature was the prevailing skin manifestation of disease with rapidly growing cutaneous and subcutaneous tumor masses arising through-out the body.

The mechanisms that predispose certain internal neoplasms to metastasize to the skin and soft tissue have not been fully elucidated. It is possible that the skin may provide a favorable microenvironment for the colonization and survival of only certain types of cancer cells, which preferentially me-tastasize to this organ [2]. The interactions between neoplastic cells and certain factors secreted from the skin or subcutaneous tissue components may play a crucial role in the skin homing mechanism of metastatic cells [2].

From a practical point of view, it should be noted that clinical manifestation of cutaneous metastases may be variable and the lesions can closely simulate not only various primary skin tumors, but even benign skin conditions, such as rash, erythema, edema or induration [4–9]. In this regard, interesting case reports have been published by Czech [9] and Slovak authors [8]. Dedková and Pock [9] described an old woman with massive cutaneous erythema from metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, which had been the first sign of this malignancy. Initially, the lesion was considered and treated as mycotic skin infection. Mego et al [8] reported a 55-year-old man with lung adenocarcinoma who had developed inflammatory skin metastases as the first sign of disease progression after previous response to chemoterapy. He experienced erythematous lesion in the left arm, which had also been initially diagnosed and treated as local cutaneous infection. In our present case, several clinical diagnoses were considered, although one of the most probable seemed to be an oncologic disease.

From a clinical perspective, cutaneous metastases generally herald a poor prognosis [1,4,5]. The average survival time of the patients is only a few months after diagnosis [1,4], which was also documented in our present case. These data indicate they are a hallmark of aggressive and widespread malignancy, often in terminal stage of the disease.

In conclusion, determining the origin of cutaneous metastases might be a challenging issue for both, clinicians and pathologists, especially when there is no primary history. The case we describe is uncommon because widespread skin and subcutaneous metastases appeared as the first and dominant clinical sign of adenocarcinoma, the origin of which has not been established. This unusual tumor behavior may suggest that a spreading and colonization of metastatic cancer cells in the skin and soft tissue may be a specific biologic process, determined by unique molecular epithelial-mesenchymal interactions.

The authors would like to thank to all the doctors in the Faculty Hospital in Žilina, who participated in diagnostic and therapeutic process of the present patient.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE recommendation for biomedical papers.

Submitted: 18. 8. 2017

Accepted: 25. 10. 2017

MUDr. PhDr. Vladimír Bartoš, PhD.

Faculty Hospital with polyclinic Žilina

Vojtecha Spanyola 43

012 07 Žilina Slovakia

e-mail: vladim.bartos@gmail.com

Sources

1. Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol 2012; 34 (4): 347–393. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31823069cf.

2. Zaky AH, El-Wanis ME, Hamza H et al. Cutaneous metastases from different internal malignancies in Egypt. Middle East J Cancer 2010; 1 (3): 135–139.

3. Handa U, Kundu R, Dimri K. Cutaneous metastasis: a study of 138 cases diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol 2017; 61 (1): 47–54. doi: 10.1159/000453252.

4. Pizinger K. Kožní metastázy. Onkologie 2010; 4 (4): 237–240.

5. Pizinger K. Kožní projevy onkologických nemocí. In: Cetkovská P, Pizinger K, Štork J. Kožní změny u interních onemocnění. 1 vydání. Praha: GRADA 2010 : 181–195.

6. Sariya D, Ruth K, Addams-McDonnell R et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol 2007; 143 (5): 613–620. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.5.613.

7. Sittart JA, Senise M. Cutaneous metastasis from internal carcinomas: a review of 45 years. An Bras Dermatol 2013; 88 (4): 541–544. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131 165.

8. Mego M, Sycova-Mila Z, Martanovic P et al. Inflammatory skin metastasis as a first sign of progression of lung cancer – a case report. Klin Onkol 2010; 23 (6): 449–451.

9. Dedková V, Pock L. Kožní metastazy karcinomu žaludku. Dermatol Praxi 2014; 8 (1): 26–28.

10. Kuklová M, Urbanček S, Menšíková J et al. Kožné metastázy ako iniciálny prejav karcinómu z buniek obličky. Čes-slov Derm 2009; 84 (5): 271–274.

11. Azoulay S, Adem C, Pelletier FL et al. Skin metastases from unknown origin: role of immunohistochemistry in the evaluation of cutaneous metastases of carcinoma of unknown origin. J Cutan Pathol 2005; 32 (8): 561–566. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00386.x.

12. Duranovič A, Tatarková I, Pizinger K. Kožní metastázy karcinomu ovária. Onkologie 2010; 4 (4): 241–242.

13. Diamantová D. Sekundární lymfedém a kožní metastázy karcinomu prsu. Remedia 2010; 20 (4): 248–249.

Labels

Paediatric clinical oncology Surgery Clinical oncology

Article was published inClinical Oncology

2018 Issue 2-

All articles in this issue

- Human Papillomavirus – Role in Cervical Carcinogenesis and Methods of Detection

- Anogenital HPV Infection as the Potential Risk Factor for Oropharyngeal Carcinoma

- Treatment of Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

- New Approaches for Chemosensitivity Testing in Malignant Diseases

- Quality of Life After High-dose Brachytherapy in Patients with Early Oral Carcinoma

- MAPK/ERK signal pathway alterations in patients with Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

- Recent Trends in Survival of Testicular Cancer Patients – Nation-wide Population Based Study

- Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Metastases of Adenocarcinoma as a Dominant Clinical Manifestation of Malignancy of Unknown Origin – a Case Report

- Diagnostic, Prognostic and Predictive Immunohistochemistry in Malignant Melanoma of the Skin

- Long Non-coding RNAs as Regulators of the Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Pathway in Cancer

- Clinical Oncology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Metastases of Adenocarcinoma as a Dominant Clinical Manifestation of Malignancy of Unknown Origin – a Case Report

- MAPK/ERK signal pathway alterations in patients with Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

- Long Non-coding RNAs as Regulators of the Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Pathway in Cancer

- Human Papillomavirus – Role in Cervical Carcinogenesis and Methods of Detection

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career