-

Medical journals

- Career

FAMILIAL HYPERCHOLESTEROLAEMIA – A DIAGNOSIS THAT EVERY PLASTIC SURGEON CAN EXPERIENCE

Authors: M. Šatný; M. Vaclová; M. Vráblík

Authors‘ workplace: Charles University, First Faculty of Medicine, and General University Hospital in Prague, 3rd Internal Department – Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Prague, Czech Republic

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 60, 2-4, 2018, pp. 54-58

INTRODUCTION

Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) is a metabolic disease caused by impaired catabolism of LDL particles, resulting in their increased plasma concentrations. LDL cholesterol accumulates in the tissues, especially in the endothelium, which inevitably leads to premature development of atherosclerotic lesions of the vascular wall with all consequences1.

EVALUATION OF THE ISSUE

Definition, Epidemiology

FH is the most common autosomal dominant inheritable disease (exceptionally autosomal recessive). Long-traced prevalence of heterozygous form of FH (heFH) – 1 : 500 – has been re-evaluated according to recent studies and is now approximately doubled – 1 : 2502,3,4,5. Converted to the population in the Czech Republic, it should be about 40,000 individuals. Prevalence is, of course, variable; there are populations affected by the so-called founder effect, for example, in Lebanon, South Africa or Quebec, Canada, where prevalence is even higher. In the light of recent studies, prevalence of the homozygous form of FH (hoFH) has been also changed from 1 : 1,000,000 to the current 1 : 300,000.

In short, a brief turning point in history, in 1938, the disease as such was first described by Norwegian Professor Carl Müller, who first linked familial xanthomas, high cholesterol, ischemic heart disease, and inherited monogenic metabolic lipid disorder6. In 1963, his work was further developed by Khachadurian, who described the heterozygous and homozygous form of FH7. Goldstein and Brown discovered the LDL receptor in 1973 and described its role in cholesterol metabolism, thus also demonstrating that FH is caused by the defect in the LDL receptor gene8. In 1985, they received the Nobel Prize for this discovery.

Untreated FH increases the risk of premature manifestation of atherosclerosis. Homozygous patients are typically affected by the atherothrombotic complication of the underlying disease before 20 years of age, and often do not live longer than 30 years, whereas in heterozygous patients, there is a manifestation of a cardiovascular event at the age of 30–50 years. Patient prognosis improved significantly after the statins were marketed in 1987. Until then, FH was a practically incurable disease9,10,11.

Pathophysiology

The FH is caused by functional impairment or complete lack of LDL receptors involved in catabolism of LDL particles in the liver. Two ligands, apolipoprotein B-100 (apoB-100) and apolipoprotein E (apoE), are required to bind the LDL particle to the hepatic receptor. Most cases of FH are caused by mutations in the gene for the LDL receptor (79%) and the genes for the already mentioned receptor ligands – apoB (5%) and apoE (1%), respectively. The FH may have exceptionally autosomal recessive hereditary forms, in practice it means that two healthy parents can have a child with a typical FH phenotype with 25% probability12.

Clinical presentation

FH patients are usually asymptomatic for a long period of time; elevated blood lipid levels are often random laboratory findings. The primary manifestation of this disease can be the cardiovascular complications, but if clinical signs are present, they are often pathognomic and should lead to further examination of these patients.

Typical signs, which a plastic surgeon can experience in his practice, are various skin lesions. These may be present in homozygous FH in the first decade of life, whereas in heterozygous FH it is usually up to about 30 years of age or later. Relatively characteristic is the fact that these skin lesions are very willing to relapse after surgical removal. To prevent their recurrence, it is important to reduce the LDL cholesterol levels significantly after this procedure. Otherwise, recurrence is not only possible but also very likely.

The frequent findings are xanthelasmas palpebrarum, subcutaneous lipid accumulations in the eyelid area (FH homozygotes can be very large and conspicuous), which are mostly located in the middle half of the upper and lower eyelids and occurring at the age of 50 years. Xanthelasmas regress well after pharmacological reduction of elevated lipid levels and therefore do not need to be surgically removed (Figure 1)13,14.

1. Xanthelasmas palpebrarum, Source: photo archive of authors´ workplace

Other possible signs may be planar xanthomas on the hands, elbows, buttocks or knees that differ from other skin xanthomas by their orange-yellow colour and are generally pathognomic for homozygous FH (Figure 2)15.

2. Planar xanthomas, Source: photo archive of authors´ workplace

In case of vague skin deposits, a biopsy is always preferred. It will eventually confirm the accumulation of lipids in the suspect deposits.

We often find tendinous xanthomas over extensors of hands, or xanthomas of the Achilles tendon, or tuberous xanthomas in the area of the hands, elbows or knees (Figure 3)15.

3. Xanthomas over a tendon of m. quadriceps femoris, Source: photo archive of authors´ workplace

These patients also have nonspecific joint pain or tendonitis that may result in their rupture, as is the case with Achilles tendon.

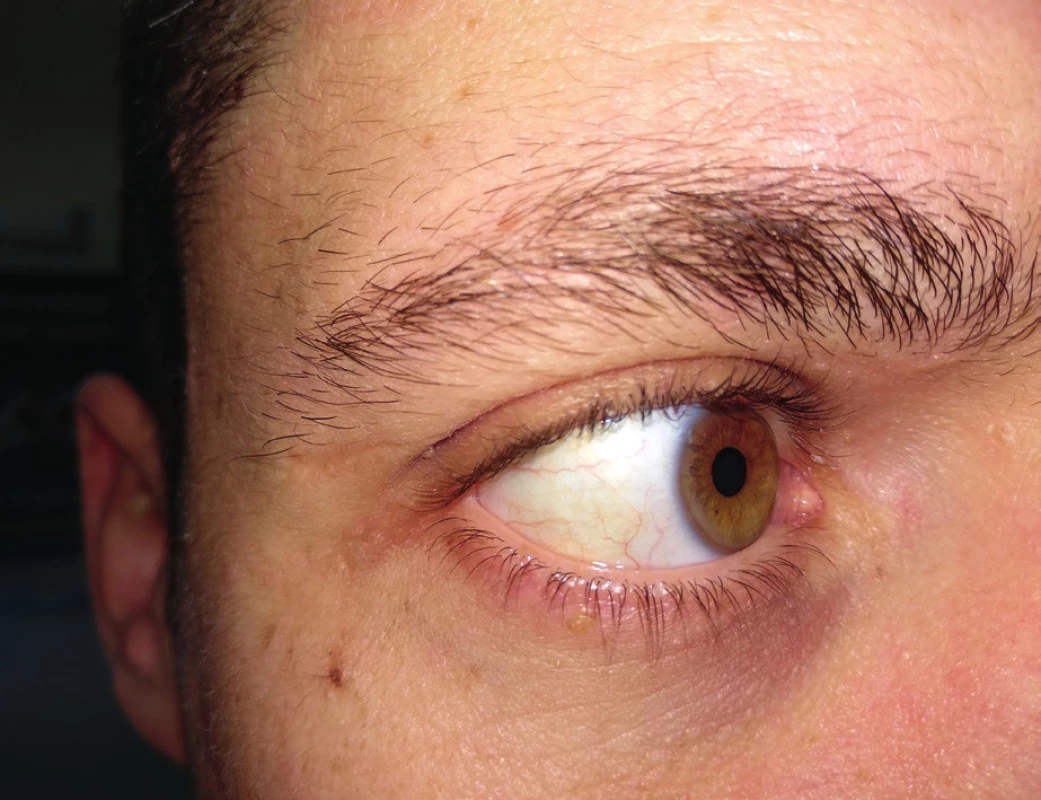

In addition, we can observe arcus lipoides corneae – greyish-white or bluish ring by corneal limbus, 1–1.5 mm wide, usually bilateral. We should be careful if we find it in patients under 50 years of age (Figure 4). If it is found in younger age than 30 years or even in children, this finding may be suspected of a very severe or even homozygous form of FH16.

4. Arcus lipoides corneae, Source: photo archive of authors´ workplace

Diagnostics

The role of the first contact with a physician is crucial here. Therefore, we should always pay attention to the above-mentioned FH signs, and patients under 50 years with signs suspected of being FH or which are willing to relapse after previous removal should be sent for further examination to a general practitioner and/or specialized centres of the MEDPED project.

MEDPED project (Make Early Diagnosis to Prevent Early Deaths in MEDical PEDigrees) is focused on the diagnostics and treatment of patients with severe dyslipidaemias to reduce the risk of premature deaths. Today, the project network consists of two national centres in Prague and one in Brno, 15 regional centres for adults and 18 specialized adult workplaces, including 10 regional centres and 7 specialized childcare facilities. In addition, seven physicians work on the project. More information about the project can be found on the website of Czech Society for Atherosclerosis: www.athero.cz.

The diagnosis of both, heterozygous and homozygous, FH, is based primarily on repeated measurement of LDL cholesterol, i.e. within one month of maintaining a low cholesterol diet, and carefully collected personal or family histories. LDL cholesterol levels above 5 mmol/l and total cholesterol over 8 mmol/l can indicate possible FH.

In addition, possible secondary causes of dyslipidaemia, especially anorexia, hypothyroidism, hepatopathy or nephrotic syndrome, should be excluded.

In personal history, we focus on the presence of symptoms of premature manifestation of cardiovascular disease, or other risk factors of atherosclerosis. In family history, we are interested in premature manifestations of coronary heart disease of parents, grandparents or siblings (myocardial infarction in men under 55 years, in women under 60 years) or severe dyslipidaemia. In both, physical examination and history (both in proband and within the family), we focus on clinical signs of FH, i.e. the presence of xanthomas, xanthelasma or arcus lipoides corneae.

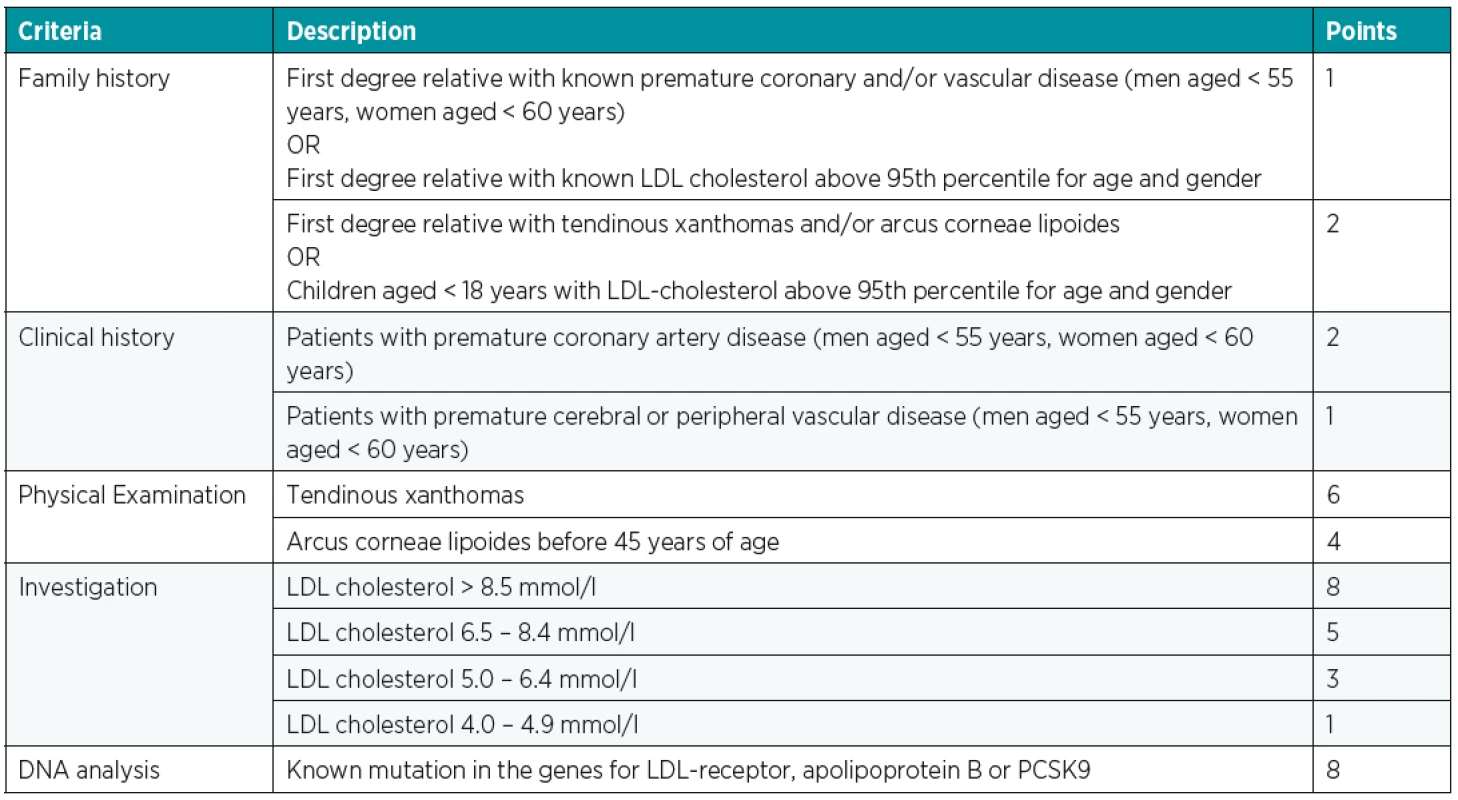

For more accurate diagnostics, we use a number of classification systems, of which the “Dutch Lipid Clinic Network Criteria” (Table 1) is the most common. These lead to a possible, probable or “definitive” FH diagnosis17.

1. Dutch Lipid Clinic Network Criteria – in each category – Family and Clinical history, Physical Examination, Investigation and DNA analysis is chosen only one possibility – the highest value; FH diagnosis: definite FH > 8 points, probable FH 6–8 points and possible FH 3–5 points. PCSK9 – proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, Source19

A definitive diagnosis is then based on a molecular genetic examination by finding a causal mutation.

In differential diagnosis, except for secondary dyslipidaemias, we should also consider polygenic familial combined hyperlipidaemia, polygenic hypercholesterolaemia, and, last but not least, very rare sitosterolaemia18.

We are also looking for preclinical atherosclerosis in these patients, so we have to repeat the ECG, echocardiography or ultrasonographic examination of the carotid arteries regularly. The examination also includes a carefully collected history of possible difficulties caused by the atherosclerotic process (stenocardia, dyspnoea, transient neurological problems, etc.) and a prompt examination of all these symptoms.

Treatment

It should be noticed that the treatment of patients with FH should be initiated at least in its initial phase in specialized lipid centres such as the MEDPED project centres. If the patient is suspected of having a possible FH, then we should refer him/her to the appropriate workplace, which is able to provide not only further examination (including genetic testing) and eventual subsequent adjustment of chronic medication, but also cascade screening, i.e. examination of other blood relatives of patient with FH.

The basis of our recommendation are, of course, lifestyle measures – low fat diet, increased physical activity and smoking cessation.

Basis of the treatment consists of high-efficiency statins at the maximum tolerated dose, often combined with ezetimibe. This treatment can lead to a reduction of LDL cholesterol levels by 50–75%, but if we still do not reach the target values, other drug groups such as resins or fibrates can be used. For the riskiest patients, PCSK9 inhibitors, as the so-called “on top therapy”, are available. These are monoclonal antibodies against subtilisin kexin 9 proprotein convertase, which is responsible for the clearance of LDL receptors on the hepatocyte surface. It is a highly potent and safe subcutaneous treatment that is currently available in two examples, namely alirocumab (Praluent) and evolocumab (Repatha).

A completely different treatment option, if we are failing to achieve target values with conventional treatment, in homozygotes, pregnant women or children with FH, is so-called LDL apheresis. Undesirable LDL particles are removed extracorporally. It is a highly efficient but invasive method, which is currently available on several workplaces in the Czech Republic.

The goals of treatment are: LDL cholesterol <1.8 mmol/l in patients without other risk factors and LDL cholesterol <1.4 mmol/l in those with manifested cardiovascular disease19.

CONCLUSION

The FH is the most common inheritable metabolic disease that, if not treated, leads to premature manifestations of atherothrombotic events, which are often fatal. There are currently approx. 19% of patients with FH diagnosed out of the estimated total number of 40,000 patients. Although the number increases year after year, most patients are still undiagnosed, and this leads to losing the possibility of treatment as well as the prevention of CVD and premature deaths. Although the diagnostics and treatment of FH is in the hands of internists, general practitioners and specialists from the MEDPED project, the physicians of other specialties, especially plastic surgeons, ophthalmologists and dermatologists, can help with the detection of a patient suspected of FH. Since the finding of one patient with FH can capture a greater number of patients in his family through cascade screening, primary care physicians are an extremely important component of this process.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: The authors declare that this study has received no financial support.

Ethical requirements: All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Martin Šatný, MD

3rd Internal Department – Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and General University Hospital in Prague

U Nemocnice 1

128 08 Prague 2

Czech Republic

E-mail: martin.satny@vfn.cz

Sources

1. Vallejo-Vaz AJ, Kondapally Seshasai SR, Cole D, Hovingh GK, Kastelein JJ, Mata P, Raal FJ, Santos RD, Soran H, Watts GF, Abifadel M, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Akram A, Alnouri F, Alonso R, Al-Rasadi K, Banach M, Bogsrud MP, Bourbon M, Bruckert E, Car J, Corral P, Descamps O, Dieplinger H, Durst R, Freiberger T, Gaspar IM, Genest J, Harada-Shiba M, Jiang L, Kayikcioglu M, Lam CS, Latkovskis G, Laufs U, Liberopoulos E, Nilsson L, Nordestgaard BG, O´Donoghue JM, Sahebkar A, Schunkert H, Shehab A, Stoll M, Su TC, Susekov A, Widén E, Catapano AL, Ray KK. Familial hypercholesterolaemia: A global call to arms. Atherosclerosis. 2015, 243 : 257–59.

2. Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Familial hypercholesterolemia: identification of a defect in the regulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase activity associated with overproduction of cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973, 70 : 2804–08.

3. Goldstein JL, Hobbs HH, Brown MS. Familial hypercholesterolemia. In: Scriver, ChR. et al. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. 8th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, Inc. 2001; 3. Vol: 2863–2914.

4. Benn M, Watts GF, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Familial hypercholesterolemia in the Danish general population: prevalence, coronary artery disease, and cholesterol-lowering medication. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012, 97 : 3956–64. (Corrigendum J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014, 99 : 4758–59).

5. Sjouke B, Kusters DM, Kindt I, Besseling J, Defesche JC, Sijbrands EJ. Homozygous autosomal dominant hypercholesterolaemia in the Netherlands: prevalence, genotype-phenotype relationship, and clinical outcome. Eur Heart J. 2015, 36 : 560–65.

6. Müller C. Angina pectoris in hereditary xanthomatosis. Arch Intern Med. 1939, 64 : 675–700.

7. Khachadurian AK. The inheritance of essential familial hypercholesterolemia. Am J Med. 1964, 37 : 402–07.

8. Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1986, 232 : 34–47.

9. Huijgen R, Kindt I, Defesche JC, Kastelein JJ. Cardiovascular risk in relation to functionality of sequence variants in the gene coding for the low-density lipoprotein receptor: a study among 29,365 individuals tested for 64 specific low-density lipoprotein-receptor sequence variants. Eur Heart J. 2012, 33 : 2325–30.

10. Cuchel M, Bruckert E, Ginsberg HN, Raal FJ, Santos RD, Hegele RA, Kuivenhoven JA, Nordestgaard BG, Descamps OS, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Watts GF, Averna M, Boileau C, Borén J, Catapano AL, Defesche JC, Hovingh GK, Humphries SE, Kovanen PT, Masana L, Pajukanta P, Parhofer KG, Ray KK, Stalenhoef AF, Stroes E, Taskinen MR, Wiegman A, Wiklund O, Chapman MJ. European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolaemia: Homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: new insights and guidance for clinicians to improve detection and clinical management. A position paper from the Consensus Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolaemia of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J. 2014, 35 : 2146–57.

11. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010, 376 : 1670–81.

12. Santos RD, Gidding SS, Hegele RA, Cuchel MA. Barter PJ, Watts GF, Baum SJ, Catapano AL, Chapman MJ, Defesche JC, Folco E, Freiberger T, Genest J, Hovingh GK, Harada-Shiba M, Humphries SE, Jackson AS, Mata P, Moriarty PM, Raal FJ, Al-Rasadi K, Ray KK, Reiner Z, Sijbrands EJ, Yamashita S. International Atherosclerosis Society Severe Familial Hypercholesterolemia Panel: Defining severe familial hypercholesterolaemia and the implications for clinical management: a consensus statement from the International Atherosclerosis Society Severe Familial Hypercholesterolemia Panel. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4 : 850–61.

13. Češka R. Familiární hypercholesterolemie. Praha:TRITON;2015.

14. Civeira F, Perez-Calahorra S, Mateo-Gallego R. Rapid resolution of xanthelasmas after treatment with alirocumab. J Clin Lipidol. 2016, 10 : 1259–61.

15. Šobra J. Familiární hypercholesterolemická xanthomatosa. Praha: Avicenum; 1970.

16. Tůmová E, Vrablík M. Arcus lipoides corneae. Med. Praxi. 2013, 10 : 395.

17. van Aalst-Cohen ES, Jansen AC, Tanck MW, Defesche JC, Trip MD, Lansberg PJ. Diagnosing familial hypercholesterolaemia: the relevance of genetic testing. Eur Heart J. 2006, 27 : 2240–46.

18. Watts GF, Gidding S, Wierzbicki AS, Toth PP, Alonso R, Brown WV, Bruckert E, Defesche J, Lin KK, Livingston M, Mata P, Parhofer KG, Raal FJ, Santos RD, Sijbrands EJ, Simpson WG, Sullivan DR, Susekov AV, Tomlinson B, Wiegman A, Yamashita S, Kastelein JJ. Integrated guidance on the care of familial hypercholesterolaemia from the International FH Foundation. Int J Cardiol. 2014, 171 : 309–25.

19. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. European Heart Journal[online]. 2019 [cit. 2019-09-01]. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. ISSN 0195-668X. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/advance-article/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455/5556353

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2018 Issue 2-4-

All articles in this issue

- ČESKÉ SOUHRNY

- Editorial

- TRANSECTION OF INFERIOR ALVEOLAR NERVE IN THE RAT – NEUROANATOMICAL STUDY AND EXPERIMENTAL MODEL

- FAMILIAL HYPERCHOLESTEROLAEMIA – A DIAGNOSIS THAT EVERY PLASTIC SURGEON CAN EXPERIENCE

- EOSINOPHILIC ANGIOCENTRIC FIBROSIS AS A CAUSE OF NASAL OBSTRUCTION. A CASE REPORT

- A COMBINATION OF HERPES VIRUS INFECTION (HSV-1, HHV-6) AND MULTI-RESISTANT BACTERIAL INFECTION IN A SEVERELY BURNED PEDIATRIC PATIENT – A CASE REPORT

- Monika Adámková, MD, from the Ostrava Burn Center has been awarded Professor Radana Königová Prize

- In Memoriam of Associate Professor Jiří Kozák, MD, PhD

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- TRANSECTION OF INFERIOR ALVEOLAR NERVE IN THE RAT – NEUROANATOMICAL STUDY AND EXPERIMENTAL MODEL

- A COMBINATION OF HERPES VIRUS INFECTION (HSV-1, HHV-6) AND MULTI-RESISTANT BACTERIAL INFECTION IN A SEVERELY BURNED PEDIATRIC PATIENT – A CASE REPORT

- FAMILIAL HYPERCHOLESTEROLAEMIA – A DIAGNOSIS THAT EVERY PLASTIC SURGEON CAN EXPERIENCE

- EOSINOPHILIC ANGIOCENTRIC FIBROSIS AS A CAUSE OF NASAL OBSTRUCTION. A CASE REPORT

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career