-

Medical journals

- Career

SURGICAL TREATMENT OF MELANOMA

Authors: K. Novotná 1; M. Arenbergerová 2; J. Miletín 1; J. Kníže 1; V. Šandera 1; K. Schwarzmannová 1; J. Bayer 1; A. Sukop 1

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Plastic Surgery, 3rd Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Královské Vinohrady University Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic 1; Department of Dermatology, 3rd Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Královské Vinohrady University Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic 2

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 59, 3-4, 2017, pp. 149-155

NATURE OF THE DISEASE

Malignant melanoma (MM) is a malignant disease of pigment cells of the basal layer of epidermis – melanocytes. These differentiate from embryonal neural crest and migrate from there to the whole body. They have therefore a great migration potential, which they re-adopt during malignant dedifferentiation and this is one of the reasons of frequent metastatic spread and aggressive behaviour of this tumour. Although it comprises only 3% of skin malignancies, it is responsible for 75% of deaths due to malignant skin tumours.1,2. Another reason for concern about this disease is its increasing incidence in the western world, and its faster increase in incidence compared to other malignancies.1

Mainly fair-skinned people with fair hair and light eyes are in danger of malignant melanoma. These people almost never get a sun tan and on the other hand they have a tendency to get a sunburn (phototype I and II according Fitzpatrick classification)1. Furthermore, the risk factor for delayed development of MM is a burn with vesicles in early childhood, exposure to UVA and UVB irradiation. Greater risk to develop MM is reported among people with greater occurrence of dysplastic nevi. There is also a slightly higher risk in 1st degree relatives of patients with melanoma. There is also a 2nd primary melanoma observed in 3–5% of patients with a history of MM in the past.3

Localization of MM in women and men differs; in women it is more common on the lower limbs, in man in cranial part of the trunk and it is related with the area of skin exposed to sun.4 Women in general have a better prognosis of MM, which is probably related with better prognosis of malignant melanoma on the limbs.

DIAGNOSTICS

In order to differentiate risky lesions from less risky, it is possible to use a simple aid, so called ABCDE rules:

A – asymmetry – irregular shape of the lesion

B – borders – unclear borders, could be blurred

C – colour – presence of two or more different shadows from brown to grey, blue to pink and red

D – diameter – diameter over 6 mm, or recent change of the size of the lesion

E – evolution/evolving/enlarging – morphological changes over a short period (months)5

Clinical description using this scheme is only supportive and the method of first choice in the diagnostics of malignant melanoma is obviously a dermatoscopic examination in the hands of an experienced dermatologist.

TYPES OF MALIGNANT MELANOMA

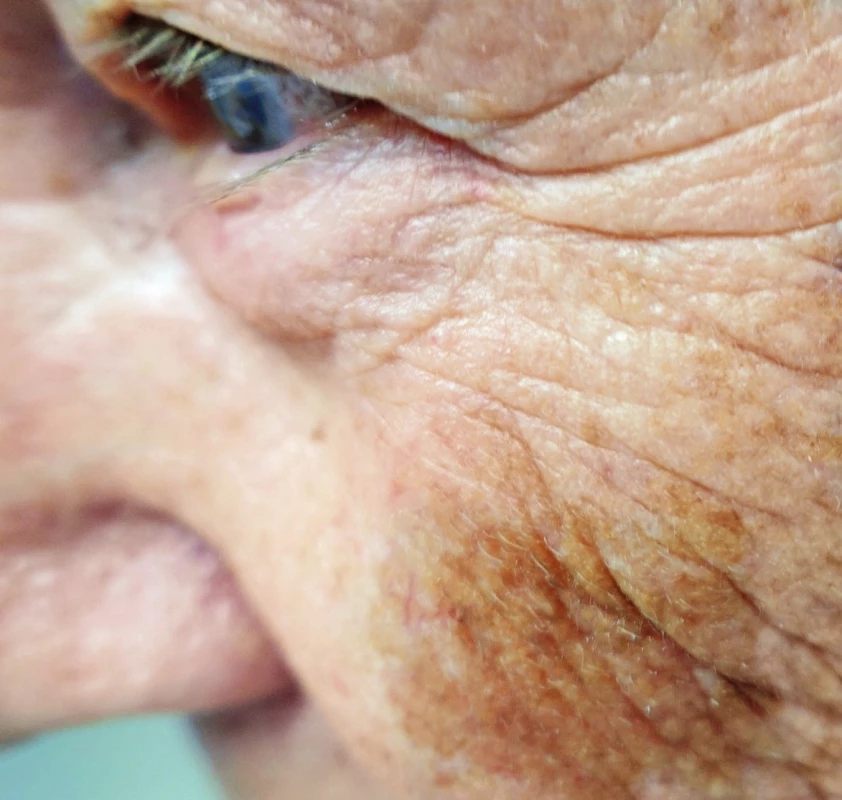

Lentigo maligna

It is a light pigmented map-shaped spot, typically on the face of the elderly, mainly women. The occurrence is mostly on skin exposed to sun.6 It can reach also a large diameter. It is a precancerosis of melanoma, melanoma without invasion, which may progress to lentigo maligna melanoma, which already shows signs of invasion. Transformation to invasive form is at 30–50%.7,8 (Fig. 1.)

Superficially spreading melanoma (SSM)

It is the most common type of MM; it comprises 60–70% of melanomas.5 It shows horizontal growth pattern in skin and therefore its prognosis during early surgical therapy is favourable.2,5 With longer duration, there may be a change of growth from horizontal to vertical; macroscopically is usually observed development of nodularity; this is then referred to as secondary nodular superficial melanoma. This change of growth dramatically worsens prognosis of the disease. (Fig. 2.)

2. Superficially spreading melanoma of the right ear

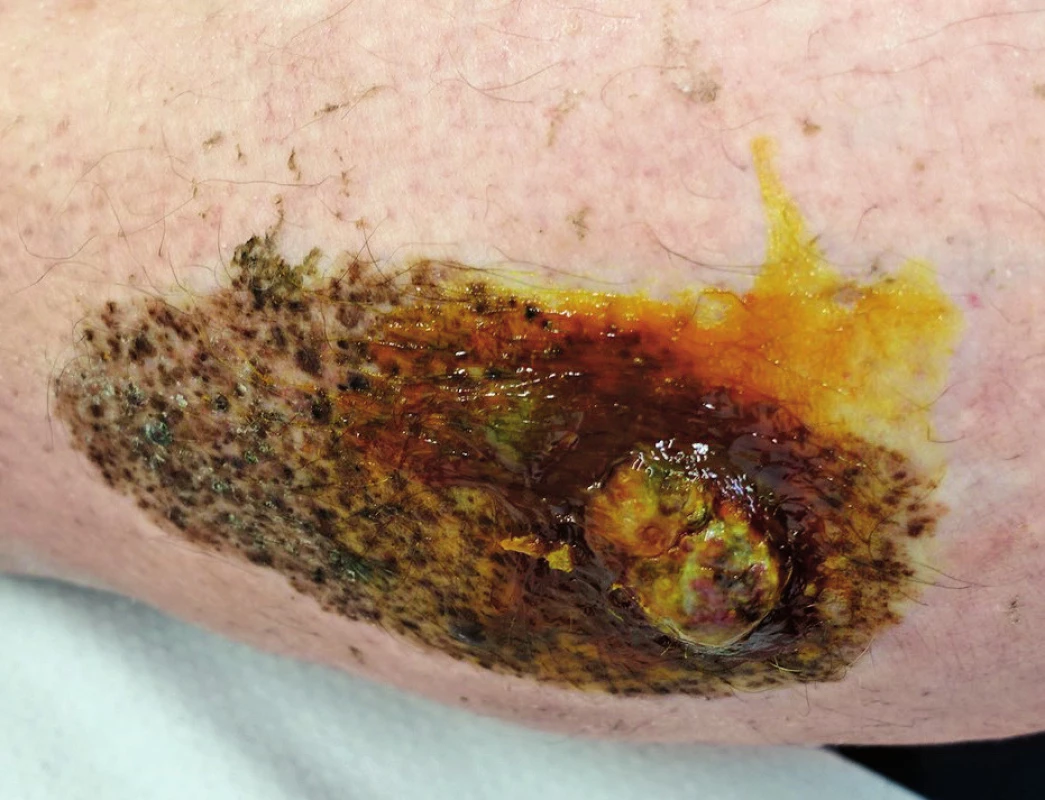

Nodular melanoma (NM)

Usually dark pigmented elevated lesion, which is primarily microscopically characterized by vertical growth, and which is the reason for poor prognosis of the disease.2 (Fig. 3.)

3. Nodular melanoma developed in a congenital nevus on the calf in a 51-year-old patient, Breslow 12 mm, Clark V

Special types of cutaneous malignant melanoma

Amelanotic melanoma

Tumour cells of amelanotic melanoma lost the ability to synthesize melanin pigment. We find inconspicuous nodular and usually pink lesion. This inconspicuous character of the lesion is the reason for common late diagnosis, and it is not an exception that it is diagnosed already in a stage of generalization, which results also in very poor prognosis.

Acral lentiginous melanoma

Specific and aggressive type of melanoma, which is not very common in the Central Europe. It is more common in population with darker skin colour, in whom the types of melanoma that are more common in our area are not very frequent.3 Acral lentiginous melanoma occurs either on the palms or on the soles, or under the nail (subungual melanoma). Subungual location may be mistaken with a hematoma after nail bed contusion. Compared to this, it has no tendency to grow away, but on the contrary, it gradually leads to ulceration in the nail area. Thumb is the most frequently affected; other fingers are rare.1 Prognosis of acral lentiginous melanoma is serious.

Mucosal melanoma, eye melanoma

Mucosal melanoma may be encountered virtually in any mucosal surface, it is most frequently observed in oral parts of the gastrointestinal tract, in the proximal part of the respiratory tract, rectum, vulva and vagina. Its poor prognosis is related with often difficult clinical examination. Mucosal melanoma affects the Asian population more frequently.10

Uveal melanoma is the most common malignant intraocular tumour.11 The group of uveal melanomas includes malignant melanoma of the iris, ciliary body and choroidea; the last is the most common.11

This subchapter is mentioned rather for completeness; it is a disease, which is not commonly treated by plastic surgeons.

Melanoma of unknown primary origin

In a small percentage of malignant melanoma patients, there is a possibility of regression of the primary tumour, and there are only metastases present. This probably occurs during an excessive growth of the tumour with its subsequent necrosis due to insufficient nutrition of a rapidly growing tumour.

CLASSIFICATION

Breslow classification

Depth of invasion in millimetres is evaluated. It is measured from the upper border of stratum granulosum of epidermis. Evaluation of invasion according to Breslow is historically the most recent classification, but it is currently considered to be the most important prognostic factor of the disease and according to its value is chosen the extent of surgical excision and possible application of adjuvant therapy.12

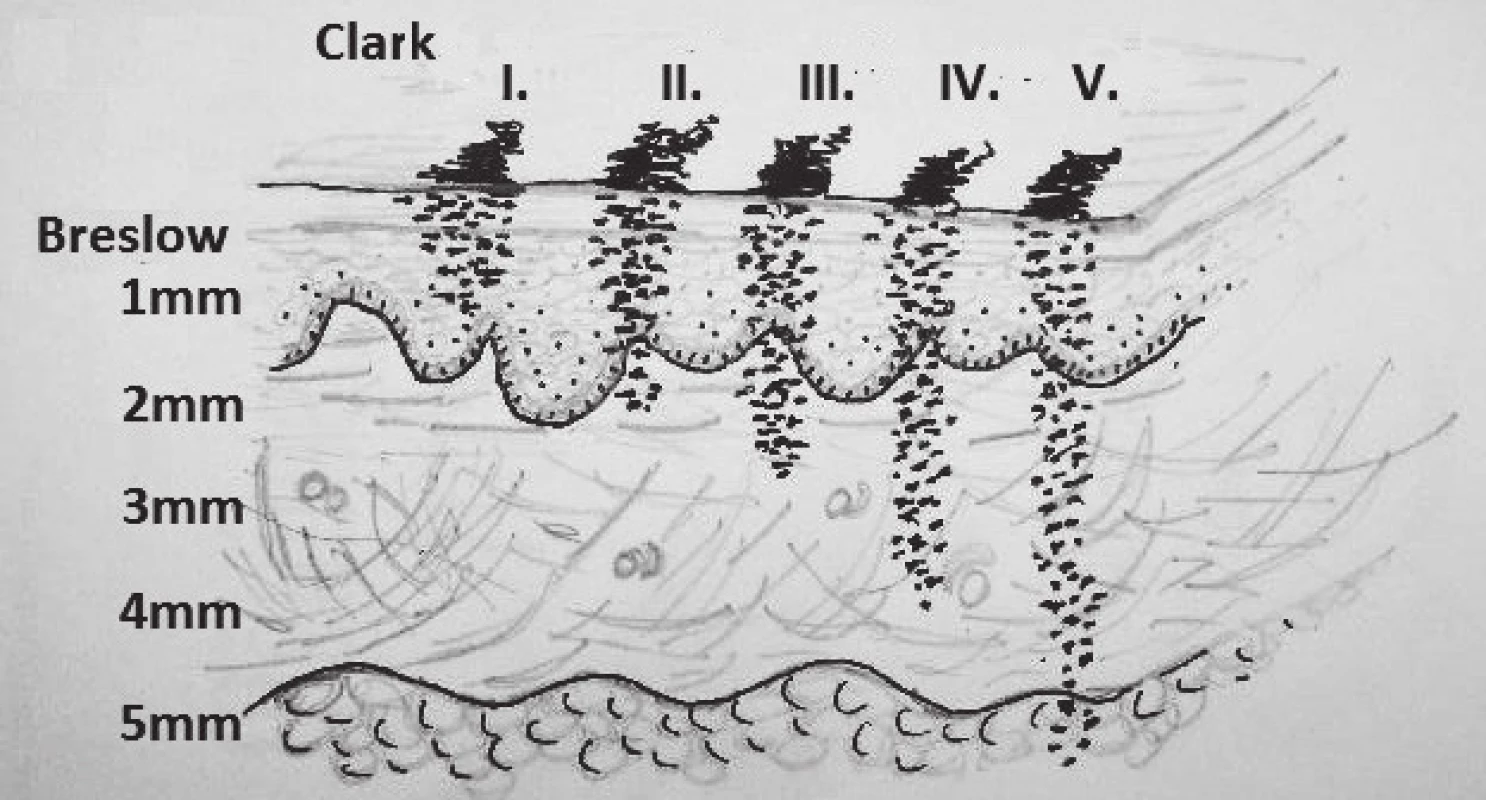

Clark classification

It is an evaluation of invasion to individual histological layers of the skin. Grades I–IV (V) are evaluated. Clark I is invasion that does not exceed the basal membrane of the epidermis, Clark II is invasion to the papillary layer of dermis, Clark III is at the border of papillary and reticular layer of dermis, Clark IV reaches to the reticular layer and sometimes is reported also Clark V, which is invasion of MM to the subcutaneous fatty tissue.13 This classification is criticized that it is associated with a subjective evaluation of the pathologist.12 (Fig. 4.)

4. Breslow, Clark classification

METASTATIC SPREAD OF MM

MM spreads early and by hematogeneous as well as lymphatic way. Lymphatic metastases are reported as satellite metastases; these are found in a distance of 2 cm from the tumour or scar after previous excision.5 Another type of lymphatic spread are so called in-transit metastases. These are present more than 2 cm from the tumour or scar and they occur in the direction towards the draining lymph nodes; they commonly create a strip of small pigmented lesions from the tumour to the regional lymph nodes.14 (Fig. 5.)

5. Satellite metastases around the scar after excision of melanoma in the interscapular area; in-transit metastases in the area of the neck dorsally on the left side

Another option of lymphatic spread is impairment of regional lymph nodes. These are micrometastases and may be detected only by histological examination or macrometastases, visible on ultrasound, CT or on palpation during clinical examination.

Hematogeneous spread of MM is most commonly to the liver, lungs, brain, bones, GIT, but virtually there is a possibility of hematogeneous spread to any organ.15

PROGNOSIS

Definite prognostic factor of malignant melanoma is depth of invasion; patients with Breslow less or equal to 1 mm have a 5-year survival of 90%, in case of invasion of 4 mm is 5-year survival only 45%. This data is the basis for the extent of surgical and adjuvant therapy.16

THERAPY

Surgical therapy

It is the treatment of first choice in most localized diseases with a relatively high chance for complete recovery.2,9 The condition is early diagnosis and sufficient radical surgical therapy. Extensive studies show that patients with malignant melanoma, in accordance with the depth of invasion in mm (Breslow), benefit from wide skin and subcutaneous tissue full thickness excision down to adjacent fascia. Previously performed excision of fascia is not performed anymore.17 The size of the resulting defect is often the reason why these patients should be treated at Plastic Surgery Units.

Width of the safety rim to healthy tissue:

- Lentigo maligna (i.e. carcinoma in situ) – 0.5 cm

- Breslow ≤ 2 mm–1 cm

- Breslow > 2 mm–2 cm1

In the US guidelines, it is possible to find the recommended rim of healthy tissue of 2 cm already from Breslow 1 mm. It is possible to adopt such an approach that a patient with melanoma benefits from every millimetre which we remove, while the minimum is 1 cm in case of invasion to 2 mm and 2 cm in case of a deeper invasion. Rim of healthy tissue is measured and marked on skin before infiltration with an anaesthetic solution; photodocumentation is usually performed in order to prevent doubts about sufficient radicality, because extensive retraction often occurs after placement of the specimen to a fixation solution.18

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SLNB)

Sentinel Lymph Node is the first lymph node that drains a particular part of the body. Its examination provides valuable information about a possible spread of melanoma, because it is the first lymph node, which drains lymph from the tumour area19. Sentinel lymph node may be detected with a radiopharmaceutical, usually Tc99 injected to the area of the tumour (performed at the Nuclear medicine unit). The signal is detected at an operation theatre with a gamma probe and a particular lymph node is removed and sent for histological examination.20 Sentinel lymph node biopsy is indicated in all melanomas with Breslow ≥ 1 mm, in prognostically more serious melanomas already in Breslow ≥ 0.75 mm. Prognostically more serious refers to melanomas with ulceration, signs of regression, count of mitoses more than 1 to 1 mm2. SLNB is a staging examination, which means that its result is used to determine further management. In case there are malignant cells found in the sentinel lymph node, dissection of regional lymph nodes should be performed. It should therefore be considered whether we perform sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients, who are not medically fit to undergo such extensive procedure as e.g. block neck dissection.21 Sentinel lymph node biopsy is not performed, if there is a suspicion of metastatic lymph node impairment; this includes palpable lymphadenopathy or ultrasound signs of tumour lymphadenopathy. Dissection of regional lymph nodes should be a part of the primary surgical therapy in such a situation.9

According to the current guidelines, it is not an error to remove a lesion of unclear nature with a 1–3 mm rim of healthy tissue and based on the result of a histological examination proceed to re-excision of the scar with sufficient rim and to possible sentinel lymph node biopsy. Aforementioned rim of 1–3 mm does not impair lymphatic drainage, therefore there will subsequently be the correct sentinel lymph node marked with a radiopharmaceutical.2

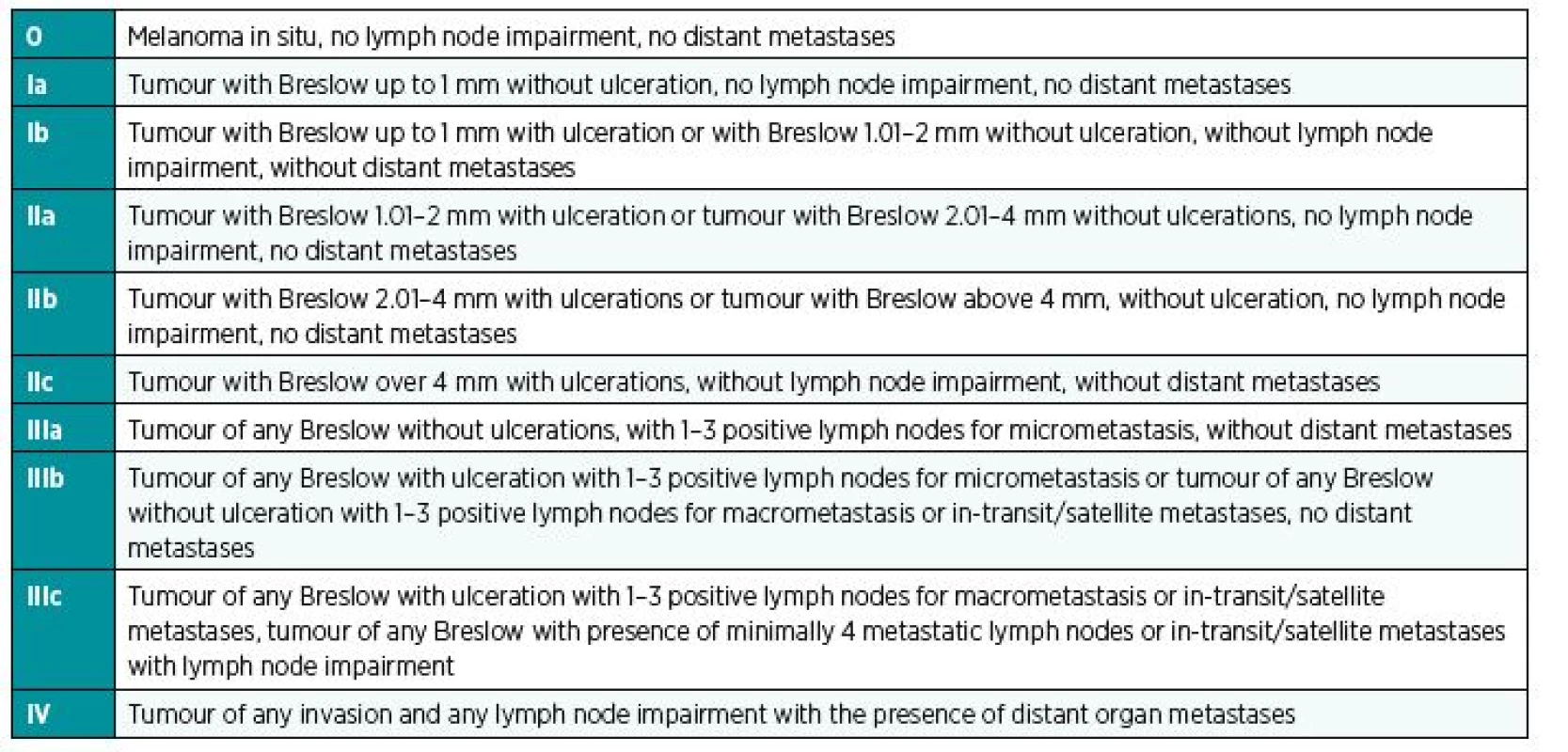

Adjuvant therapy of malignant melanoma – review of current options

Adjuvant therapy in patients with melanoma is indicated based on the stage of the disease, from stage IIB inclusive (Table 1).2

1. Stages of malignant melanoma<sup>22</sup>

Immunotherapy

INF alpha. Interferon alpha is a cytokine, which improves anti-tumour immunity with a mechanism, which is not clear yet.5 It is used for adjuvant treatment of melanoma patients and prolongs progression free survival. There are 3 various dosing schedules used worldwide. Their results are comparable. INF alpha is usually administered for 12–24 months as a subcutaneous injection 3 times a week, which is managed by the patients alone at home usually quite well.5 Early adverse effect of INF alpha therapy includes so called “flu-like” syndrome, which is comprised of fever, fatigue, and joint pain. It has been treated with symptomatic therapy.

Ipilimumab. It is a monoclonal antibody targeting CTLA 4 receptor of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Binding to CTLA 4 receptor results in stimulation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and thereby in stimulation of antitumor immunity.23 This antibody acts also against other malignancies.

Pembrolizumab, Nivolumab. This is a human IgG4 anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody (PD = programmed death). Similarly to antibodies against CTLA 4, also these activate immunocompetent cells and thereby non-specifically reduce escape of tumour cells from the action of the immune system.24

Since immunostimulating antibodies against PD 1 and CTLA 4 act to different receptors, it has been demonstrated in clinical studies that their combination, particularly Ipilimumab and Nivolumab, results in prolongation of progression free survival and overall survival in patients with non-resectable MM.25

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy means that there is a therapeutic intervention performed directly to the replication cascade using a specific inhibitor; this results in stopping of the division of tumour cells.

BRAF inhibitors – Dabrafenib, Vemurafenib

Skin melanomas in more than a half of the cases are associated with mutation in the BRAF gene, particularly BRAF V600E, based on which occurs activation of replication cascade with subsequent uncontrolled division of melanoma cells. Inhibitor of BRAF protein blocks this cascade with subsequent regression of the disease.26

MEK inhibitors – Trametinib, Cobimetinib

They influence the next step of the replication cascade, i.e. immediately after BRAF inhibitors, with a similar mechanism.

Recent studies show that patients with BRAF mutation benefit from combined therapy using MEK and BRAF inhibitor. There is prolongation of progression free survival and overall survival with regression of adverse effects of targeted melanoma therapy (specific skin toxicity - hyperkeratosis of soles and palms, development of skin papillomas and spinocellular carcinomas).26 Unfortunately, resistance on targeted antibodies in monotherapy and in combination occurs within months and years, which results in a relapse of the disease. (Fig. 6, 7, 8.)

6. Patient with a recurrence of melanoma in a scar above scapula on the left after sufficient wide excision

7. Patient after six months of combined therapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitor

8. Patient 4 months after radical surgical procedure

Chemotherapy

This chapter is included for completeness. With regards to the current use of modern and much more efficient treatment options during the recent decades, usage of chemotherapy in non-resectable malignant melanomas is subsiding. Some units still use Dacarbazine in monotherapy in specific cases.

Specific treatment options in MM

Hyperthermic limb perfusion

This method had been repeatedly used in the past and was abandoned already from the 50’ of the 20th century and it is currently experiencing a comeback. It requires a specific patient – disease localized only to a single limb, particularly distal part of thigh and more distally, or distal arm and more distally. This method is complicated and demanding for the patient. The affected limb is perfused with a concentrated cytostatic solution heated usually to 40–41˚C after cannulation of the arterial and venous system and it uses Melphalan, Dacarbazine, Cisplatine and TNFα.27,28

Radiotherapy

It is reserved for specific situations in patients with MM and it is usually based on an agreement of a multidisciplinary team. This may be considered e.g. as an adjuvant radiotherapy after excision of satellite or in-transit metastases, excision of extensive mucosal melanomas, dissection of significantly impaired lymph nodes, which is however commonly associated with lymphedema. Furthermore, it is used as a palliative therapy of metastases to the brain or extensive non-resectable in-transit or lymph node metastases.29

Intralesional application of cytostatics

MM spreads specifically to the skin, and therefore these lesions are easily accessible to local treatment in terms of cauterization or intralesional application of cytostatics. This is of course palliative therapy rather than curative.2

CONCLUSION

Malignant melanoma is, despite great therapeutic advances in recent two decades, especially in biological therapy, still a malignant disease with a very serious prognosis and it has a rising incidence, where the hope for complete recovery is only in patients with early detection of the disease. Therefore, every suspicious skin lesion should be excised and histologically examined. When confirming the diagnosis of melanoma, there should be re-excision of scar with sufficient rim of healthy tissue performed and according to the depth of invasion should also be possibly performed sentinel lymph node biopsy. Every patient with the diagnosis of melanoma should be followed in a unit by an experienced team and available modern adjuvant therapy.

Figures 1, 2, 3, 8 source: Department of Plastic Surgery, Královské Vinohrady University Hospital

Figures 4, 5, 6, 7 source: author

Corresponding author:

Klára Novotná, M.D.

Department of Plastic Surgery, 3rd Faculty of Medicine, Charles University

and Královské Vinohrady University Hospital

Šrobárova 50, 100 34 Prague 10, Czech Republic

E-mail: klara.novotna@fnkv.cz

Sources

1. Brown DL, Borschel GH, Levi B. Michigan manual of plastic surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014.

2. Fong ZV, Tanabe KK. Comparison of melanoma guidelines in the U.S.A., Canada, Europe, Australia and New Zealand: a critical appraisal and comprehensive review. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Jan;170(1):20-30.

3. Cafardi, Jennifer. The manual of dermatology. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

4. Johnston, Ronald. Weedon’s Skin Pathology Essentials E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2016.

5. Kružicová Z. Maligní melanom. Postgraduální medicína. [online]. 2010 [cit. 2016-06-15]. Available from: http://zdravi.euro.cz/clanek/postgradualni-medicina/maligni-melanom-450829

6. Kasprzak JM, Xu YG. Diagnosis and management of lentigo maligna: a review. Drugs Context. 2015 May 29;4 : 212281.

7. Wilson JB, Walling HW, Scupham RK, Bean AK, Ceilley RI, Goetz KE. Staged Excision for Lentigo Maligna and Lentigo Maligna Melanoma: Analysis of Surgical Margins and Long-term Recurrence in 68 Cases from a Single Practice. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016 Jun;9(6):25-30.

8. Stevenson O, Ahmed I. Lentigo maligna: prognosis and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(3):151-64.

9. Garbe C, Peris K, Hauschild A et al. Diagnosis and treatment of melanoma. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline – Update 2016. Eur J Cancer. 2016 Aug;63 : 201-17.

10. Mihajlovic M, Vlajkovic S, Jovanovic P, Stefanovic V. Primary mucosal melanomas: a comprehensive review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5(8):739-53.

11. Intraocular (Uveal) Melanoma Treatment (PDQ®) – Health Professional Version. In: National Cancer Institute [online]. 2015 [cit. 2016-6-15]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/types/eye/hp/intraocular-melanoma-treatment-pdq

12. Dickson PV, Gershenwald JE. Staging and prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2011 Jan;20(1):1-17.DOI: 10.1016/j.soc.2010.09.007. ISSN 1055-3207.

13. Povýšil C., Šteiner I. Speciální patologie. Druhé, doplněné a přepracované vydání. Praha: Galén, 2007.

14. Hayes AJ, Clark MA, Harries M, Thomas JM. Management of in-transit metastases from cutaneous malignant melanoma. Br J Surg. 2004 Jun;91(6):673-82.

15. Tas F. Metastatic behavior in melanoma: timing, pattern, survival, and influencing factors. J Oncol. 2012;2012 : 647684.

16. Tan WW. Malignant melanoma. In: Medscape [online]. 2016 [cit. 2016-6-15]. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/280245-overview

17. Grotz TE, Markovic SN, Erickson LA et al. Mayo Clinic consensus recommendations for the depth of excision in primary cutaneous melanoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011 Jun;86(6):522-8.

18. Bichakjian CK, Halpern AC, Johnson TM et al. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Nov;65(5):1032-47.

19. Balch ChM, Charles M, Thompson JF, Faries MB. The Clinical Value of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy In Melanoma Staging, Regional Disease Control, and Survival: The Melanoma Letter. Summer 2015, Vol. 33, No. 1. In: Skin Cancer Foundation [online]. 2015 [cit. 2016-6-15]. Available from: http://www.skincancer.org/publications/the-melanoma-letter/summer-2015-vol-33-no-1/sentinel

20. Lloyd MS, Topping A, Allan R, Powell B. Contraindications to sentinel lymph node biopsy in cutaneous malignant melanoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2004 Dec;57(8):725-7.

21. Wong SL, Balch CM, Hurley P et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology joint clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Aug 10;30(23):2912-8.

22. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classifica-tion. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Dec 20;27(36):6199-206.

23. Fellner C. Ipilimumab (yervoy) prolongs survival in advanced melanoma: serious side effects and a hefty price tag may limit its use. P T. 2012 Sep;37(9):503-30.

24. Carbognin L, Pilotto S, Milella M et al. Differential Activity of Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab and MPDL3280A according to the Tumor Expression of Programmed Death-Ligand-1 (PD-L1): Sensitivity Analysis of Trials in Melanoma, Lung and Genitourinary Cancers. PLoS One. 2015 Jun 18;10(6):e0130142.

25. Diamantopoulos P, Gogas H. Melanoma immunotherapy dominates the field. Ann Transl Med. 2016 Jul;4(14):269.

26. Krajsová I. Kožní melanom: diagnostika, léčba a pooperační sledování. Czecho-Slovak Dermatology / Cesko-Slovenska Dermatologie [serial online]. November 2012;87(5):163-175.

27. Špaček M, Mitáš P, Lacina L. Cytostatická hypertermická perfuze izolované končetiny (HILP) ve VFN. Rozhl. Chir. 2011, 90(1), 62-66.

28. Simone MD, Vaira M. Hyperthermic Isolated Limb Perfusion. In: Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet]. Austin (TX): Landes Bioscience; 2000–2013. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6461/

29. Khan MK, Khan N, Almasan A, Macklis R. Future of radiation therapy for malignant melanoma in an era of newer, more effective biological agents. Onco Targets Ther. 2011;4 : 137-48

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2017 Issue 3-4-

All articles in this issue

- Editorial

- PATIENT SATISFACTION AFTER BREAST RECONSTRUCTION: IMPLANTS VS. AUTOLOGOUS TISSUES

- OLEOGEL-S10 TO ACCELERATE HEALING OF DONOR SITES: MONOCENTRIC RESULTS OF PHASE III CLINICAL TRIAL

- THE NASOLABIAL FLAP: THE MOST VERSATILE METHOD IN FACIAL RECONSTRUCTION

- CURRENT TREATMENT OPTIONS OF DUPUYTREN´S DISEASE

- SURGICAL TREATMENT OF MELANOMA

- POSTOPERATIVE FIXATION AFTER REPOSITIONING OF PREMAXILLA IN A PATIENT WITH BILATERAL CLEFT LIP AND PALATE – CASE REPORT

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- THE NASOLABIAL FLAP: THE MOST VERSATILE METHOD IN FACIAL RECONSTRUCTION

- CURRENT TREATMENT OPTIONS OF DUPUYTREN´S DISEASE

- PATIENT SATISFACTION AFTER BREAST RECONSTRUCTION: IMPLANTS VS. AUTOLOGOUS TISSUES

- OLEOGEL-S10 TO ACCELERATE HEALING OF DONOR SITES: MONOCENTRIC RESULTS OF PHASE III CLINICAL TRIAL

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career