-

Medical journals

- Career

Epilepsy with Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures in an Adolescent Patient – A Case Study

21. 5. 2024

This is the story of Anička, a 16-year-old girl who has been treated for epilepsy since she was 14. Her condition is accompanied by generalized tonic-clonic seizures, which may need to be managed acutely with rescue medication, either at home or at school. Instead of the previously used rectally administered diazepam, a new, safer and more comfortable option for rescue medication is now available: buccally administered midazolam. This modality may also help alleviate anxiety and other psychological impacts related to the condition, as illustrated by our case study.

Before her first seizure, Anička was healthy and had never suffered from any serious illnesses. Her mother had been treated for epilepsy during childhood, but there is no detailed documentation, and the mother does not remember the seizures. She stopped taking medication during puberty and has been trouble-free since. Anička has a sister who is three years older and has no medical issues.

Anička is a very talented girl who is in the first year of high school, studies excellently, and has honors. She is part of a dance group and is a very good painter. She would like to work as a teacher. She is very responsible, goal-oriented, and a perfectionist, sensitive and anxious from an early age but always managed without the help of a psychologist.

First Seizure

Anička had her first seizure at a summer camp where her friend in the tent was awakened by gurgling noises early in the morning. She saw Anička having limb jerks and called the camp leader, who then called emergency services and brought Anička to the hospital. After a thorough discussion, we found out that she had been experiencing some problems for a few months before the first seizure, where sometimes in the early morning she would drop a cup or bowl from her hand because of arm jerking, without knowing why. She thought she was just sleepy and did not pay much attention to it. Thus, epilepsy was only addressed after the first major seizure. She does not remember the seizure and had no warning signs.

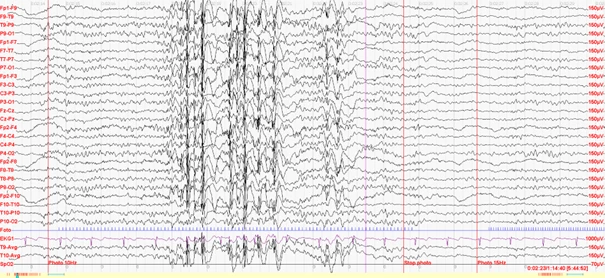

We conducted an EEG, which showed typical generalized epileptiform discharges (see fig.), confirming the diagnosis of idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE), likely juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) in this case. It is not necessary to conduct a brain MRI with this diagnosis, but one was performed for Anička, showing typical negative results.

Fig. EEG finding typical for the diagnosis of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Generalized discharges of spike-wave complexes or multiple spike-wave complexes at frequencies of 3–6 Hz lasting several seconds. Typically, as in this case, they are accentuated by photostimulation. During these discharges, myoclonic jerks in the head or limb regions (myoclonic jerks) can be observed.

Epilepsy with Typical Onset During Adolescence

This type of epilepsy clinically manifests in adolescence, often presenting with a major (generalized tonic-clonic) seizure. There might be a history of limb jerks (myoclonic seizures) or absences. Epilepsy can be associated with anxiety, depressive moods, attention disorders, or other ADHD symptoms (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder).

This epilepsy syndrome type is very sensitive to lifestyle modifications. Patients must maintain proper sleep hygiene, avoid alcohol and flashing lights. Therefore, the first manifestation typically occurs during adolescence when the patient stays up late at a party with strobe lights and consumes alcohol, often leading to the first generalized tonic-clonic seizure in the early morning. If JME is diagnosed, we start antiepileptic medication and educate the patient about strict adherence to lifestyle modifications. If the diagnosis is accepted responsibly, the likelihood of seizure recurrence can be minimized. However, the treatment with antiepileptic medication is lifelong.

Rescue Medication

Besides prophylactic chronic medication taken daily, we can also equip the patient with rescue medication, which allows a caregiver to manage a seizure at home. For many years, rectal diazepam has been available, administered as a suppository into the rectum. It comes as a small tube with a long applicator part inserted into the rectum, and the gel content is administered by squeezing the tube. Patients carry it with them or it is provided to their caregivers – family, friends. Rescue medication is administered if the seizure lasts longer than 3 minutes – at that point, the likelihood of spontaneous seizure cessation is low, and there is a risk of developing status epilepticus.

We prescribed levetiracetam for Anička, gradually increasing the dose to a target of 2 g/day, and she was equipped with 10 mg rectal diazepam for acute use during a seizure. During dose escalation, she had another generalized tonic-clonic seizure at school during the first lesson. The teacher was educated on first aid and administered diazepam.

Psychological Impacts of the Condition and How to Mitigate Them

Here, it needs to be said that Anička was very unhappy with her epilepsy and feared the seizures. She was not reconciled with the diagnosis and became very withdrawn. Following the school incident, the situation significantly worsened. She was afraid to go to school, did not want to see friends, and was ashamed of her illness. Her sleep was poor, and her anxiety worsened, making her tearful and sad. After consulting a pediatric neurologist, her parents visited a child psychologist who started working with Anička. The psychologist found that she was very troubled by the shame of potentially having to undergo another medication application into the rectum in public, in front of her classmates, which is understandable, especially during adolescence. Systematic work with the psychologist helped Anička significantly, and she gradually became more reconciled with the diagnosis, learned to live with epilepsy, and worked on handling stressful situations that epilepsy might bring.

The introduction of the new rescue medication to the market was a significant positive. Now, we have buccal midazolam, administered into the buccal pouch (between the teeth and cheek) in a very simple syringe form. We prescribed Anička with buccal midazolam 10 mg and instructed her parents on its application. However, the instruction is also very clearly explained in the leaflet. Anička felt a great relief. The prospect of having another seizure in the presence of classmates or other people is now much more acceptable to her, and she is not afraid of the buccal application of rescue medication, which is not as stigmatizing as the rectal application.

Conclusion

The patient titrated her chronic medication, adheres to lifestyle modifications, her EEG is now normal, and she feels very well. She visits the psychologist regularly and works on her anxiety with very positive feedback. So far, there has been no recurrence of seizures. However, she is prepared to handle any should they occur.

doc. MUDr. Pavlína Danhofer, Ph.D.

Clinic of Child Neurology, LF MU and FN Brno

Did you like this article? Would you like to comment on it? Write to us. We are interested in your opinion. We will not publish it, but we will gladly answer you.

Labels

Neurology Paediatrics General practitioner for children and adolescents

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career