-

Medical journals

- Career

IMPAIRED HEALING AFTER SURGERY FOR FEMORAL FRACTURES IN POLYTRAUMA PATIENTS

Authors: Karel Šmejkal; Jan Šimek; Tomáš Dědek; Jiří Páral

Authors‘ workplace: Hradec Králové, Chirurgická klinika, Oddělení úrazové chirurgie ; Fakulta vojenského zdravotnictví Hradec Králové, Univerzita obrany v Brně, Katedra vojenské chirurgie, Fakultní nemocnice

Published in: Úraz chir. 27., 2020, č.4

Overview

INTRODUCTION: Femoral fractures are most often the result of a high-energy mechanism. Their primary treatment, definitive management and addressing of impaired healing are still a matter of discussion. AIM: The aim of the study was to analyse the causes of impaired healing of femur, infectious complications and their possible solutions.

METHODOLOGY: It is a retrospective study of 1,433 patients from years 2014 to 2018. We focused on a group of polytrauma patients with NISS > 15, who also suffered a diaphyseal or distal femur fracture. Of this cohort, 178 patients died. Of the remaining 998 patients with NISS > 15, 82 patients (8 %) suffered a concomitant diaphyseal or distal femur fracture.

RESULTS: The fracture healed without the need for further intervention in 84 % of cases. In two patients (2.6 %), the condition was assessed as prolonged healing. Primary non-healing occurred in a total of 6 patients (8 %).

DISCUSSION: Replacement of the nail with a thicker nail after reaming the medullary cavity and with the possible addition of positional screws is most commonly used to manage the impaired healing of femur. The success rate of this technique ranges from 75 to 100 %. Another possible surgical technique is the augmentation of the existing nail with an additional plate, which has proven to be particularly successful in the infraisthmic portion of the diaphysis, i.e. in the distal third. The success rate of this method exceeds 90 %. The third possible surgical technique is a conversion of intra-articular osteosynthesis to plate osteosynthesis. Its importance is seen in the necessary conversion of relative to absolute stability.

CONCLUSION: The causes of impaired bone healing are mechanical, biological, and a combination of both. The mechanical cause may be insufficient stability or, on the contrary, excessive rigidity of the osteosynthesis, which does not result in muscle formation. The biological cause is most often a malnutrition of the fracture fragments. Then, by discovering the cause of the impaired healing, we can achieve healing with the right intervention.

Keywords:

surgical treatment – Multiple trauma – femoral fracture – impaired healing

INTRODUCTION

Femoral fractures are most often the result of a highenergy mechanism. Their primary treatment, definitive management and addressing of impaired healing are still a matter of discussion. Impaired healing of femur is a socioeconomic problem. Particularly for young people, their return to work plays an important role. There is a number of factors that have a demonstrable effect on bone healing, such as smoking, medication with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, comorbidities (diabetes, etc.), and many others. In our study, we recapitulate the success rate of surgical treatment of the femur and the possibilities of managing the impaired healing.

AIM

The aim of the study was to analyse the causes of impaired healing of femur, infectious complications and their possible solutions.

METHODOLOGY

It is a retrospective study of complications from years 2014 to 2018. We focused on a group of polytrauma patients, who also suffered a diaphyseal or distal femur fracture. We monitored the incidence of impaired healing, infectious complications and their management. The baseline criterion for enrolment in the cohort was a fracture of the diaphysis and the distal third of the femur as a part of the polytrauma.

From 1/2014 to 12/2018, we treated a total of 1,433 patients with NISS > 15, who were older than 16 and were transported to the traumacentre of the University Hospital Hradec Králové, whether primarily or secondarily. Of this cohort, 178 patients died. Of the remaining 998 patients with NISS > 15, 82 patients (8 %) suffered a concomitant diaphyseal or distal femur fracture. In this cohort, 5 patients were followed up or treated at the patient’s surgical centres after the surgery, and thus we were not able to monitor their condition up to the end. Of the remaining 77 patients, 49 cases involved a diaphyseal femur fracture. In ten cases there was a fracture of the distal portion of the femur and in 18 cases there was a segmental fracture.

Exclusion criteria were age below 16 years, fractures of proximal femur (including subtrochanteric fractures), and monotrauma. Patients with isolated diaphyseal femur fracture (monotrauma) were deliberately excluded. This group contained 71 patients over the same time period, i.e. from 1/2014 to 12/2018. They are often elderly patients with osteoporosis. Fractures are often caused by an indirect low-energy mechanism and the surgical treatment strategy may also be different.

The patient monitoring length was minimally 12 months. Patients were followed up at regular monthly intervals. No one died during the monitoring! The average age of patients was 39. Men predominated in 80% of the cases. 29 patients (38 %) suffered an open fracture. The fracture was considered healed if the fracture line was healed in at least ¾ of the circumference of the cortical bone according to the X-ray documentation.

RESULTS

For primary treatment, we applied an external fixator in 72 cases (94 %) as part of the „damage control surgery“. Definitive surgery, regardless of the site of fracture, was performed using retrograde nailing of DFN Distal femoral nail (DePuy Synthes, Switzerland) in 44 % (n=33). We also used UFN Unreamed femoral nail (DePuy Synthes, Switzerland) in 14 % (n=11). In 12 % (n=9), we used PFN - A long Proximal femoral nail (DePuy Synthes, Switzerland). In 10 % (n=8), we used LCP Locking compression plate (DePuy Synthes, Switzerland) for diaphyseal fractures and in 9 % (n=7), we used LCP for distal femur. We used the combination of DFN and DHS Dynamic hip screw (DePuy Synthes, Switzerland) in 9 % (n=7), and finally we used the Universal nail (DePuy Synthes, Switzerland) in one case (1%) and a combination of the plate for distal femur and DHS plate in one case (1 %).

The fracture healed without the need for further intervention in 84 % of cases. In two patients (2.6 %), the condition was assessed as prolonged healing. In both of them we performed only outpatient dynamization of the nail under local anaesthesia with an interval of about 8 - 9 months, which resulted in strengthening of the already forming callus and subsequent healing of the fracture. In one case, it was a short oblique fracture in the distal metaphysis region. The second case was a triple fracture under the isthmus in a patient with traumatic amputation of the same-sided lower limb in the tibia, in whom it was difficult to dose the load of the limb with stepping. Primary non-healing occurred in a total of 6 patients (8 %). Respectively four times in the diaphyseal region (8 %) and twice in the distal portion of the femur (20 %). Segmental fractures have always healed.

Femoral diaphyseal fractures that did not heal were primarily treated with an intramedullary nail in three cases (75 %) and with a pair of titanium plates in one case. The nail was reamed twice. On one occasion, we performed nailing without reaming having regard to an open comminuted fracture of the diaphysis. Three patients suffered an open fracture (75 %) and only one patient suffered a closed fracture (25 %). One fracture was a simple transverse to short oblique fracture (25 %) and three fractures were triangular (75 %).

The solution that resulted in final healing was to strengthen the stability once by introducing positional screws together with dynamization of the nail in the original transverse fracture (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Insufficient stability of the intramedullary nail – managed by dynamization of the nail and reinforcement of stability by positional screws, a) unhealed simple fracture of the diaphysis after retrograde DFN (distal femoral nail) nailing 6 months after the injury, b) healed after dynamization of the retained nail in situ and reinforcement of stability by positional screws – 6 months after revision surgery

On one occasion, we addressed the impaired healing by adding a mixture of autologous and allogeneic spongioplasty to the defective region. The defect developed after removal of avital bone fragments during primary treatment and repeated dressings of the open comminuted fracture. The fracture was subsequently treated by osteosynthesis with two plates – lateral and helical (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Post-traumatic defect and lack of stability using the bridging plate technique – managed by enhancing stability by adding a second plate and spongioplasty, a) unhealed comminuted diaphyseal fracture after plate osteosynthesis, b) healed after adding a second (helical) plate and spongioplasty – 6 months after revision surgery

On one occasion we managed the impaired healing by augmentation of the existing DFN with a 3.5 mm DCP (Dynamic compression plate), including decortication and spongioplasty in a comminuted fracture.

In the last case, a comminuted fracture as well, we operated in two periods. Firstly, by re-milling the medullary cavity and replacing the original 11 mm UFN with a thicker 14 mm Universal nail. However, there was no healing. Therefore, we further converted the Universal nail to plate osteosynthesis including decortication and spongioplasty (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Insufficient healing of a comminuted fracture of the diaphysis after intramedullary nailing osteosynthesis – managed by conversion to plate osteosynthesis with spongioplasty, a) healing only around the periphery of the bone with a central defect after antegrade UFN (Unreamed femoral nail) nailing b) healed after conversion to plate osteosynthesis and filling the defect with spongy bone – 6 months after revision and 18 months after primary surgery

In the last three cases mentioned (i.e., 75 % of commuted fractures), signs of healing were present from the beginning, but healing occurred only along the periphery of the bone (diaphysis) due to primary dislocation of bone fragments. The residual central defect was therefore treated as a nonunion.

Fractures of the distal femur that did not heal were primarily treated with a reamed and statically secured DFN for a closed C2 fracture in one case and a distal femur plate for an open C3 fracture in one case. Thus, these were always fractures with a comminuted zone in the metaphysis (100 %).

The solution that resulted in the final healing was to re-mill the medullary cavity once and replace the original 10 mm DFN with a thicker 13 mm DFN, along with enhancing the stability by introducing the positional screws (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Healing failure after treatment of distal metadiaphyseal fracture with spiral interfragment, managed by conversion to a thicker reamed retrograde nail in combination with positional screws, a) unhealed fracture with an interfragment after retrograde DFN (Distal femoral nail) nailing after 6 months from trauma, b) healed after milling of the medullary cavity and replacement of the nail with a thicker one in combination with positional screws – 6 months after revision surgery

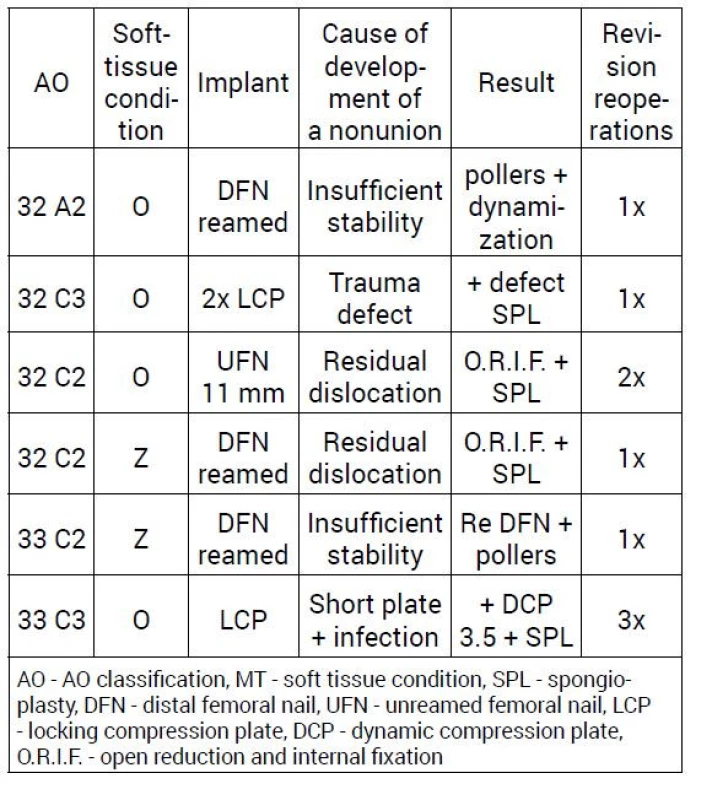

In the second case, the primary steel LCP for the distal femur from the external side was supplemented with a second 3.5 mm plate from the medial side, including allogenic spongioplasty to the comminuted zone in the metaphysis, at the planned interval of 12 weeks. Here, however, the osteosynthesis failed or the relatively short place (with respect to the length of the fracture line – comminuted zone) was released from the outside with subsequent infectious complication. The solution was replacement of steel plates with titanium and longer ones and temporary implantation of Septopal® local antibiotic carrier (Zimmer Biomet) including systemic treatment of the infection with the antibiotics Piperacillin/Tazobactam 4.5 g Pfizer® intravenously after 8 hours (Fig. 5, Tab. 1).

Fig. 5: Impaired healing after treatment of distal metaphyseal fracture with a plate from the external side with stability enhancement using an additional plate in phase two – complicated by infection and loss of stability – managed by reosteosynthesis after healing the infection, a) osteosynthesis of comminuted fracture of distal metaphyseal with LCP (Locking compression plate) from the external side, b) planned stability enhancement with an additional plate from the inner side and spongioplasty - 12 weeks after primary osteosynthesis, c) release (failure) of the plate on the outer side with infectious complication – 18 weeks from the previous operation, d) healed after the healing of infection including Septopal® implantation and replacement of steel implants with titanium ones – 12 months from primary osteosynthesis

1. Cause of the development of nonunion and its management

Infectious complications were treated in four patients (5 %). In two cases there was a primary open fracture. The first patient also suffered a simultaneous knee joint dislocation. Despite the reduction, stabilization with an external fixator, vascular reconstruction and subsequently fasciotomy, necrosis of the calf muscle groups gradually occurred with a septic condition after three weeks. Severe overall condition required amputation of the lower limb in the thigh.

In the second patient, a hematoma in the thigh after an open fracture became contaminated with clostridial agents after 7 days. We performed repeated drains, lavages, sequestrotomies and repeated fillings of the bone defect with cement filling with antibiotic (Gentamicin, LEK Pharmaceutical D.D., Ljubljana). The fracture was stabilized first with an external fixator and then after 5 months with a titanium plate. Eventually we were forced to amputate the lower limb in the thigh in this case as well.

In the third patient, 15 days after insertion of the PFN - A long nail, the postoperative hematoma also became contaminated with Staphylococcus aureus and the nail had to be extracted. The fracture was stabilized with an external fixator. Milling of the medullary cavity, lavage after removal of the nail and implantation of Septopal were performed. The infection was managed and after 8 weeks we converted the fixator to a titanium plate including autologous spongioplasty.

The last patient had a postoperative hematoma contaminated with Staphylococcus epidermidis after plate osteosynthesis. The cause was an overdose of anticoagulation prophylaxis. We managed the condition by means of revision, drainage and replacement of the steel plate with a titanium one less than 3 weeks after the primary surgery.

DISCUSSION

It is necessary to take into account the characteristics of our cohort, which consists of patients with severe polytrauma. Fractures are always the result of highenergy trauma and the severity of their overall condition also negatively affects the body‘s biological capacity for bone healing.

The incidence of impaired healing in the area of diaphysis of the femur in our cohort is consistent with data reported in the literature, ranging between 5 % and 12 % [5]. Prolonged healing can be defined as a condition in which healing has not occurred for 6 months after surgery. Nonunion is a condition in which the bone does not heal within 9 months after the surgery or if there are no signs of healing progress for three consecutive months on the radiographs.

Impaired healing occurs most often with residual distraction at the fracture line, insufficient stability of osteosynthesis, interposition of soft tissues into the fracture line [8], or soft tissue damage due to trauma or surgical technique with impaired bone nutrition. Other negative factors include infectious complications and smoking.

Replacement of the nail with a thicker nail after reaming the medullary cavity with the possible addition of positional screws is most commonly used to manage the non-healing of femur. The success rate of this technique ranges from 75 to 100 % [3, 4, 5, 6, 12]. During the reaming, the endosteal blood supply and almost one half of the width of the cortical bone is reduced, but the blood supply to the periosteum is reciprocally increased up to sixfold. During the reaming, pluripotent stem cells, growth factors and osteoblasts are released into the fracture site. So we can talk about the so-called autospongioplasty [2, 3]. Potential adverse effects of the reaming, such as the development of compartment syndrome, ARDS (Acute respiratory distress syndrome), etc., were not confirmed in numerous studies [3, 4]. A thicker nail also represents a more stable osteosynthesis with respect to increasing its contact surface, which is in contact with the inner surface of the cortical bone. Adding positional screws to shorten the working distance will enhance stability. The lower success rate, according to some papers [10], can probably be attributed to the more liberal use of this technique even in atrophic and defective nonunions. In the case of a hypertrophic nonunion, replacement of the nail with a thicker one with the reaming of the medullary cavity and eventual strengthening of the stability with positional screws is the method of first choice in our department.

In the nailing of multifragment fractures, while maintaining the principle of relative stability, direct manipulation of the dislocated fragments primarily in an attempt to bring them closer, or to attach them to the nail, is a possible threat to their vitality. We therefore face the question of how much residual dislocation is still acceptable or will result in a callus bridging [8]. Here, it seems to be more important to preserve the residual blood supply to the fragments, even at the cost of the possible need for future surgical intervention using the open approach in phase two. In our opinion, in such fractures, it is not a mistake to convert the originally multifractured fracture into the form of a nonunion on the residual simple fracture line, which can be managed in phase two by the absolute stability technique using a plate. It is important to stress that we are not talking about grossly dislocated cortical bone fragments (in open fractures). Fragments without soft tissue hinge are deprived of nutrition. Those have no positive effect on further healing and are intended to be removed so that they do not become future sequesters.

Another possible surgical technique for the management of impaired healing is the augmentation of the existing nail with an additional plate, which we have proved to be particularly successful in the infraisthmic portion of the diaphysis, i.e. in the distal third. The success rate of this method exceeds 90 % [6, 7, 11, 13]. Studies comparing this technique with the simple nail over nail method or open reduction and conversion to plate osteosynthesis speak in favour of strengthening the nail with a single 3.5 mm plate. The purpose is to strengthen stability, especially the rotational one. At the same time, decortication and spongioplasty can also be performed in a relatively less invasive manner.

The third possible surgical technique in the management of impaired healing is the conversion of intra-medullary osteosynthesis to plate osteosynthesis. This method is invasive, thus associated with higher blood loss and soft tissue stripping. Its importance is seen in the necessary conversion of relative to absolute stability. This is in the case when the originally comminuted fracture, treated with a nail on the principle of relative stability, has matured into a nonunion on a residual simple fracture line that can be compressed with lag screws. Or in the case when the inserted bone graft needs to be anchored. The technique of one or sometimes better two plates can be used [1, 9]. The disadvantage of plate osteosynthesis with one plate is the impossibility of loading the limb with weight and stress acting on both ends of the plate with the risk of stress fracture and also the risk of refracture after possible removal of the plate in the future. In fractures of the distal portion of the femur, where we are forced to use primarily a plate due to the localisation of the fracture line from the joint, it is beneficial to supplement the plate on the outer side with a plate from the inner side. In plate osteosynthesis of comminuted fractures in metaphysis, it is sometimes problematic to determine the correct working distance on the plate from the outside only. The scope of motion on the inner cortical surface may be excessive and will not result in the formation of a callus [11].

CONCLUSION

When analysing the causes of impaired healing in our cohort, three most common causes can be traced.

The first is the lack of stability in simple transverse (short oblique) fractures where all micro-movement is concentrated in this one short fracture line. Unlike in comminuted fractures, where there is a better distribution of micro-motion between the individual fracture lines. Simple fractures require stabilization with a secured and sufficiently wide nail, even with the use of positional screws that can shorten the working distance. Another cause of impaired healing is the residual dislocation of fragments in multifracture fractures. Closed or interference reduction can correct the position of the axis, length and rotation of the femur; however, the position of individual fragments can only be repaired partially (to a certain extent).

Another negative factor is the development of infectious complications that have a negative effect on bone healing.

Typical examples of diaphyseal fractures, where problems with healing can be expected, are on the one hand open and multifractured fractures, caused by a direct mechanism. Especially those where the fragments are not in any contact with each other.

And on the other hand, simple transverse or shortly oblique fractures, where we did not achieve a sufficient degree of stability with a reamed thick nail including positional screws.

Sources

1. CHENG, T., XIA R, YX, LUO, C. Double-plating fixation of comminuted femoral shaft fractures with concomitant thoracic trauma. J Int Med Res. 2018, 46, 440–447.

2. DUAN, X., LI, T., MOHAMMED, AQ et al. Reamed intramedullary nailing versus unreamed intramedullary nailing for shaft fracture of femur: A systematic literature review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011, 131, 1445–1452.

3. GÄNSSLEN, A., GÖSLING, T., HILDEBRAND, F. et al. Femoral shaft fractures in adults: treatment options and controversies. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2014, 81, 108–117.

4. HIERHOLZER, C., GLOWALLA, C., HERRLER, M. et al. Reamed intramedullary exchange nailing: treatment of choice of aseptic femoral shaft nonunion. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014, 9. URL:https:// josr-online.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13018-014 - 0088-1.

5. KIM, JW, YOON, YC, OH, CW et al. Exchange nailing with enhanced distal fixation is effective for the treatment of infraisthmal femoral nonunions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2018, 138, 27–34.

6. LAI, PJ, HSU, YH, CHOU, YC et al. Augmentative antirotational plating provided a significantly higher union rate than exchanging reamed nailing in treatment for femoral shaft aseptic atrophic nonunion - retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019, 20.URL: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral. com/articles/10.1186/s12891-019-2514-3.

7. LIN, CJ, CHIANG, CC, WU, PK et al. Effectiveness of plate augmentation for femoral shaft nonunion after nailing. J Chin Med Assoc. 2012, 75, 396–401.

8. LIN, SJ, CHEN, CL, PENG, KT et al. Effect of fragmentary displacement and morphology in the treatment of comminuted femoral shaft fractures with an intramedullary nail. Injury. 2014, 45, 752 – 756.

9. PENG, Y., JI, X., ZHANG, L. et al. Double locking plate fixation for femoral shaft nonunion. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2016, 26, 501–507.

10. RU, J., CHEN, L., HU, F. et al. Factors associated with development of re-nonunion after primary revision in femoral shaft nonunion subsequent to failed intramedullary nailing. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018, 13. URL: https://josr-online.biomedcentral. com/articles/10.1186/s13018-018-0886-y.

11. ŠMEJKAL, K., LOCHMAN, P., TRLICA, J. et al. Poruchy hojení po operační léčbě zlomenin stehenní kosti. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2015, 82, 358–363.

12. SOMFORD, MP, VAN, DB, KLOEN, P. Operative treatment for femoral shaft nonunions, a systematic review of the literature. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2013, 8, 77–88.

13. ZHANG, W., ZHANG, Z., LI, J. et al. Clinical outcomes of femoral shaft non-union: dual plating versus exchange nailing with augmentation plating. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018,13.URL:https://josronline. biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13018-018-1002-z.

Labels

Surgery Traumatology Trauma surgery

Article was published inTrauma Surgery

2020 Issue 4-

All articles in this issue

- Prof. MUDr. PETROVI HAVRÁNKOVI, CSc., FEBPS K 70. NAROZENINÁM

- Prim. MUDr. VLADIMÍR POKORNÝ, CSc. – 90. LET

- IMPAIRED HEALING AFTER SURGERY FOR FEMORAL FRACTURES IN POLYTRAUMA PATIENTS

- COMPUTER-ASSISTED CT NAVIGATION OF POSTERIOR PELVIC SEGMENT OSTEOSYNTHESIS - A CASE REPORT

- REINSERTION OF RUPTURE OF THE DISTAL BICEPS BRACHII TENDON - OUR EXPERIENCE

- INTERNAL OSTEOSYNTHESIS OF DORSAL FRACTURES OF THE PROXIMAL TIBIA

- JOINT SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH CENTRE - BIOMECHANICAL LABORATORY OF THE UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL OSTRAVA

- Trauma Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- REINSERTION OF RUPTURE OF THE DISTAL BICEPS BRACHII TENDON - OUR EXPERIENCE

- INTERNAL OSTEOSYNTHESIS OF DORSAL FRACTURES OF THE PROXIMAL TIBIA

- IMPAIRED HEALING AFTER SURGERY FOR FEMORAL FRACTURES IN POLYTRAUMA PATIENTS

- COMPUTER-ASSISTED CT NAVIGATION OF POSTERIOR PELVIC SEGMENT OSTEOSYNTHESIS - A CASE REPORT

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career