-

Medical journals

- Career

Liver transplantation using grafts from donors after circulatory death – the first Czech Republic experience

Authors: J. Froněk 1,2,6; R. Novotný 1; M. Kucera 1,6; J. Mendl 1; M. Kocík 1; P. Trunecka 3; P. Taimr 3; E. Kieslichová 4; E. Pokorná 5; L. Janousek 1,6

Authors‘ workplace: Transplant Surgery Department, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague 1; Department of Anatomy, 2nd Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague 2; Department of Hepatology, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague 3; Department of Anesthesiology, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague 4; Department of Organ Collection and Transplantation Databases, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague 5; 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague 6

Published in: Rozhl. Chir., 2020, roč. 99, č. 9, s. 391-396.

Category:

doi: https://doi.org/10.33699/PIS.2020.99.9.391–396Overview

Introduction: Liver transplantation is established as a lifesaving procedure for patients with acute and chronic liver failure, as well as certain selected malignancies. Due to a continuing organ shortage and ever-growing patient waiting lists, donation after cardiac death (DCD) is becoming more frequently utilized in order to close the gap between “supply and demand”.

Methods: A retrospective analysis of DCD and subsequent liver transplantations was performed.

Results: From May 2016 to September 2019, a total of 9 DCD liver transplantations were performed in our institution. All cases except one were primary liver transplantations. The recipients comprised 5 (56%) males and 4 (44%) females. The mean DCD donor age was 41±12 (22–57) years, with ventilation duration of 7±1 days and warm ischemia time 19±3 minutes. The average recipient age was 51±22 (4–73) years, with an average cold ischemia 3h:59m±27m and manipulation time of 23±5 minutes. Periprocedural mortality was 1 (11%). Hepatitis C recurrence was documented in 1 (11%) patient. The mean follow-up time was 19±13 (7–37) months. Until now, we have not observed any signs of ischemic cholangiopathy.

Conclusion: DCD liver transplantation allows us to enlarge the pool of potential liver grafts, thus decreasing the time spent on the liver recipient waiting list. This paper documents the first series of DCD liver transplantations in the Czech Republic.

Keywords:

Transplantation – liver – Donation after Circulatory Death donor – first experience

Introduction

Liver transplantation (LTx) is established as a lifesaving procedure for patients with acute and chronic liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma [1]. In 1970, the donor liver pool was changed after Harvard Medical school proposed the implementation of the brain death criterion [2]. Donation after circulatory death donors (DCD) have been known as a “behind the curtain” cadaveric organ option. The ever expanding waiting lists for LTx necessitated the use of marginal liver donors [3]. This inevitably forced the Institute of Medicine Committee to conclude in 2006 that DCD organs can be utilized to close the donor-recipient gap [2,4]. Currently, the DCD liver graft pool accounts for up to 10% of all LTx in the USA and more than 30% of those in the UK [5].

There are two liver transplant centers in the Czech Republic. The first liver transplantation in the Czech Republic was performed in Brno in 1983. The first LTx in the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine (IKEM) took place in 1995. Between 1994 and 2019, we performed some 1885 LTx in IKEM. The first ever DCD LTx in the Czech Republic was performed in IKEM in 2016.

Every year, over a million people worldwide die of liver cirrhosis [6]. IKEM is the largest transplant center in the Czech Republic, where in 2019 alone, 154 LTx were performed. LTx is the only effective treatment for end-stage liver disease, and it extends life expectancy by 17 to 22 years [7,8]. Due to continued organ shortage and ever-growing waiting lists, DCDs are becoming more frequently utilized in order to fill the gap between “supply and demand”. Liver transplantation is no exception in this trend as rates of liver failure are constantly increasing.

Most of the patients on the waiting list can be recipients of donation after brain death (DBD) livers. Since 2012, we have made significant changes to the liver transplant program, including donor criteria and acceptance (split liver, donor over 70, reduced expanded criteria donor (ECD) grafts, live donor LTx for children); DCD LTx is one of the novelties we implemented. Thanks to these changes, the number of LTx at our institution keeps growing every year (Graph 1). The first ever DCD LTx in the Czech Republic was performed in IKEM in May 2016. Nine successful DCD liver transplants have been performed at IKEM to date.

Methods

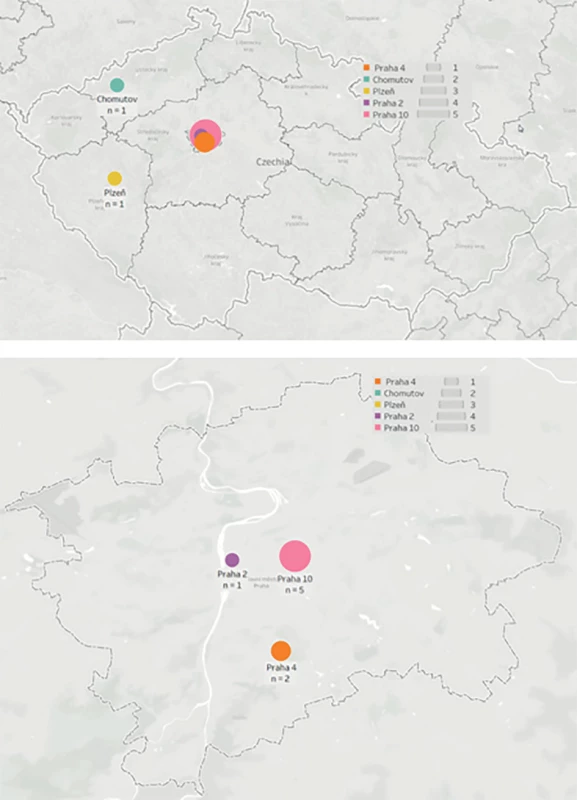

All potential donors who met the criteria for DCD were referred for organ retrieval to the Transplant Coordination Centre of the Czech Republic. If a suitable match was found for a recipient placed on the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine (IKEM) LTx waiting list, the transplant team was then alerted and dispatched to the local hospital for organ retrieval (Fig. 1).

1. Geographical dispersion of death after circulatory arrest donors in the Czech Republic used for liver retrieval by the transplant team ofthe Transplant Surgery Department, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine

The no-touch interval of 5 minutes was crucial for the success of the liver harvest and subsequent transplantation. Terminal extubation was always performed either in the operating theatre or the intensive care unit (ICU). From the point of view of organ retrieval, theatre extubations are preferred to ICU extubations because they offer a shorter warm ischemia time after the no-touch interval. The “waiting time” until cardiac arrest can be set individually by each transplant center since there are no specific guidelines that recommend an optimum waiting time. IKEM has a maximum waiting time of 2 hours for DCD liver and/or kidney retrieval. If the waiting time prior to cardiac arrest surpassed 2 hours, organ retrieval was cancelled.

DCD organ retrieval was performed using a modified super rapid retrieval (SRR) method. The modification of SRR: a sharp laparotomy, rapid cannulation of the aorta via the external iliac artery using a double-balloon catheter, and a venous outflow cut. Once the macroscopic quality of the organs was confirmed, the recipient was transported to the operating theatre. The entire retrieval procedure was performed by a consultant transplant surgeon and a junior assistant. Approximately one minute elapsed between knife-to-skin and the start of perfusion.

We performed the DCD LTx in the same way we would have used for a liver from a DBD donor, with portal reperfusion first and arterial (re)perfusion second. In order to attain a short CIT, the recipient is moved to the theatre once the macroscopy of the liver is known. Once the retrieval team is back from distant retrieval, the transplant recipient surgery begins immediately. The immunosuppression protocol did not vary from that of a DBD, which utilizes steroid induction and triple maintenance therapy.

Results

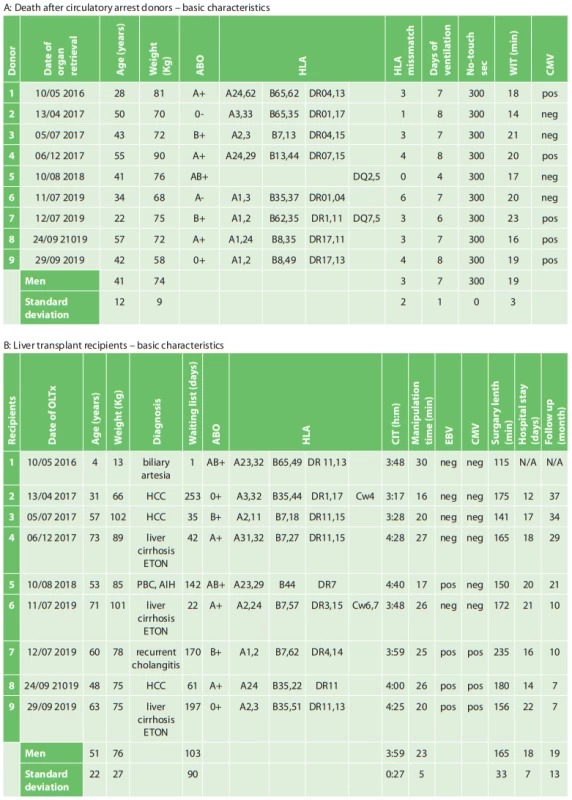

From May 2016 to September 2019, there were a total of 26 DCD offers, nine of which were DCD LTx. The remaining 15 livers were contraindicated during the retrieval, mainly for macroscopic findings. All cases involved primary LTx except one. The recipients comprised 5 (56%) females and 4 (44%) males. The average DCD donor age was 41±12 (22–57) years, with ventilation duration of 7±1 days and warm ischemia time 19±3 minutes. The average recipient age was 51±22 (4–73) years, with mean cold ischemia duration of 3h:59m±27m and the manipulation (anastomotic) time of 23±5 minutes. Periprocedural mortality was observed in 1 patient (11%). This patient underwent a repeated orthotopic liver transplant (OLTx) for primary non-function of the first graft, which was a reduced left liver segment. After de-clamping the inferior vena cava and re-perfusing the transplanted graft, the patient became hemodynamically unstable. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was immediately initiated. Electromechanical dissociation combined with bradycardia led to “mors in tabula”. Hepatitis C recurrence was evident in 1 (11%) patient (Tab. 1). The mean follow-up time after the DCD LTx in our study was 19±13 (7–37) months.

1. Basic characteristics of death after circulatory arrest donors and subsequent liver transplant recipients

Abbreviations: HCC – Hepatocellular carcinoma; Liver cirrhosis ETOH – Alcoholic liver cirrhosis; PBC – Primary biliary cholangitis; AIH – Autoimmune hepatitis After the DCD LTx, none of the cases developed acute renal failure.All graftsbegan to work immediately, with no indication of primary non-function. None of the patients required re-transplantation, and after OLTx, their aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase(ALT) parameters became normalized before they were discharged from IKEM (Graph 1). Most surprising is the fact that none of the DCD LTx patients developed ischemic cholangiopathy, which is probably the most frequent and also long-term graft/patient compromising complication after the DCD LTx.

1. Aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) parameters as they developed in time after liver transplantation from DCD donors

(a) AST developed after OLTx from a DCD donor; (b) ALT developed after OLTx from a DCD donor 2. Number of liver transplants performed in the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine (IKEM) between 1994-2019

Discussion

According to the Maastricht criteria, DCD liver donors can be placed into two categories – controlled and uncontrolled. Maastricht category III – controlled DCD is the most widely used mode for DCD LTx [9]. The use of Maastricht categories I and II for DCD LTx has opened a potentially significant donor pool not previously utilized. However, this comes at the cost of a higher incidence of post - DCD LTx complications, such as ischemic type biliary lesions, primary non-function, and increased re-transplantation rates, in comparison to organs from DBD donors [4, 10–12].

The Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients has clearly shown a decreased survival rate of DCD LTx patients vs DBD LTx patients [13]. High donor age is associated with an increased risk of recipient complications, including ischemic cholangiopathy, graft loss, and mortality. Firl DJ et al. demonstrated that advanced donor age alone does not necessarily increase the risk of graft failure in DCD LTx [14]. Croome KP et al. reported an improved rate of survival in patients after DCD LTx over the past decade [15]. Furthermore, Abraham T et al. indicated a major decrease in ischemic complications after DCD LTx due to cautious selection of donors and recipients when scrutinizing the criteria such as donor and recipient age, donor body mass index, graft steatosis, and anatomical variations in the vasculature [16].

Machine perfusion is becoming widely accepted as it is known to optimize marginal grafts for transplantation. Hypothermic oxygenation perfusion (HOPE) was introduced for DCD LTx in 2012, with the premise of improving DCD LTx results [17,18]. Based on experimental data, HOPE is known to positively impact primary antioxidative mitochondrial effects, subsequently reducing the reperfusion injury and improving early LTx function. Schlegel A et al. demonstrated superior results of HOPE treated DCD LTx in comparison to untreated LTx [19,20]. We use cold oxygenated machine perfusion only for DBD extended criteria donor livers. We decided to run the DCD liver program differently, aiming for a minimal cold ischemic time. Since we did not observe any of the usual complications related to DCD LTx, we are optimistic about our approach. Of course, the series of DCD LTx is still limited. Our intention is to continue pursuing a short CIT. With increasing numbers of patients being placed on waiting lists, there is no shortage of recipients who may benefit from DCD LTx.

Conclusion

The maturation DCD transplantation program at the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine continues with the aim to improve DCD liver transplantation results. Furthermore, it allows us to enlarge the pool of potential liver grafts, thus decreasing time spent on the liver recipient waiting list.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all institutions in the Czech Republic that take part in the DCD program.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in connection with this paper and that the article has not been published in any other journal, except congress abstracts and clinical guidelines.

MUDr. Jiri Fronek, Ph.D, FRCS

Transplant Surgery Department

Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine

e-mail: jiri.fronek@ikem.cz

Sources

1. Graziadei I, Zoller H, Fickert P, et al. Indications for liver transplantation in adults: Recommendations of the Austrian Society for Gastroenterology and Hepatology (ÖGGH) in cooperation with the Austrian Society for Transplantation, Transfusion and Genetics (ATX). Wien KlinWochenschr. 2016;128(19-20):679–690. doi:10.1007/s00508-016-1046-1.

2. Steinbrook R. Organ donation after cardiac death. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):209–213.

3. Rana A, Price MB, Barrett SC, et al. Aggressive utilization of liver allografts: Improved outcomes over time. Clin Transplant. 2020 [On line] doi: 10.1111/ctr.13860.

4. Reich DJ, Hong JC. Current status of donation after cardiac death liver transplantation. CurrOpin Organ Transplant. 2010;15(3):316–321. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32833991e3.

5. Sharma H, Tun Abraham M, Lozano P, et al. DCD liver transplant: a meta-review of the evidence and current optimization strategies. Curr Transpl Rep. 2018;153–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-018-0193-x.

6. Byass P. The global burden of liver disease: a challenge for methods and for public health. BMC Med. 2014;12 : 159. doi:10.1186/s12916-014-0159-5.

7. Taylor R, Allen E, Richards JA, et al. Survival advantage for patients acceptingthe offer of a circulatory death liver transplant. J Hepatol. 2019;70(5):855–865. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.12.033.

8. Strong R, Fawcett J. 20-year survival post-liver transplant: much more is needed! Hepatol Int. 2015;9(3):339–341. doi: 10.1007/s12072-015-9617-1.

9. Steinbrook R. Organ donation after cardiac death. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):209–213.

10. Biggins SW, Gralla J, Dodge JL, et al. Survival benefit of repeat liver transplantation in the United States: a serial MELD analysis by hepatitis C status and donor risk index. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(11):2588–2594. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12867.

11. Dubbeld J, Hoekstra H, Farid W, et al. Similar liver transplantation survival with selected cardiac death donors and brain death donors. Br J Surg. 2010;97(5):744–753. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7043.

12. Blasi A, Hessheimer AJ, Beltrán J, et al. Liver transplant from unexpected donation after circulatory determination of death donors: a challenge in perioperative management. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(6):1901–1908.

13. Jay C, Ladner D, Wang E, et al. A comprehensive risk assessment of mortality following donation after cardiac death liver transplant—an analysis of the national registry. J Hepatol. 2011;55(4):808–813.

14. Firl DJ, Hashimoto K, O’Rourke C, et al. Impact of donor age in liver transplantation from donation after circulatory death donors: a decade of experience at Cleveland Clinic. Liver Transpl. 2015;21(12):1494–1503.

15. Croome KP, Lee DD, Keaveny AP, et al. Improving national results in liver transplantation using grafts from donation after cardiac death donors. Transplantation 2016;100(12):2640–2647.

16. Tun Abraham M. Is there a learning curve in donation after cardiac death liver transplant: a Canadian single-centreexperience. In: Congress of the International Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association. 2016: Sao Paulo, Brazil.

17. Schlegel A, Muller X, Dutkowski P. Hypothermic liver perfusion. CurrOpin Organ Transplant. 2017;22(6):563–570. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000472.

18. Dutkowski P, Schlegel A, de Oliveira M, et al. HOPE for human liver grafts obtained from donors after cardiac death. J Hepatol. 2014;60(4):765–772. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.023.

19. Schlegel A, Muller X, Kalisvaart M, et al. Outcomes of DCD liver transplantation using organs treated by hypothermic oxygenated perfusion before implantation. J Hepatol. 2019;70(1):50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.005.

20. Czigany Z, Lurje I, Schmelzle M, et al. Ischemia-reperfusion injury in marginal liver grafts and the role of hypothermic machine perfusion: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9 : 846.

Labels

Surgery Orthopaedics Trauma surgery

Article was published inPerspectives in Surgery

2020 Issue 9-

All articles in this issue

- Circulating matrix metaloproteinases as biomarkers in colorectalcancer

- Changes in normothermia during surgery

- Surgical treatment of extensive perianal hidradenitis

- Je nutné zjišťovat dopady covidu-19 na chirurgická pracoviště?

- Incarcerated lumbar hernia in the Petit´s triangle as a cause of large bowel obstruction

- Recommendations for patient management after manual reduction of incarcerated inguinal hernia: a literature review

- Liver transplantation using grafts from donors after circulatory death – the first Czech Republic experience

- Extensive bile duct injury resulting from a laparoscopic cholecystectomy resolved by a Roux-en-Y tri-hepaticojejunostomy: a case report

- Perspectives in Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Surgical treatment of extensive perianal hidradenitis

- Incarcerated lumbar hernia in the Petit´s triangle as a cause of large bowel obstruction

- Changes in normothermia during surgery

- Extensive bile duct injury resulting from a laparoscopic cholecystectomy resolved by a Roux-en-Y tri-hepaticojejunostomy: a case report

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career