-

Medical journals

- Career

Laparoscopic treatment of bowel perforation after blunt abdominal trauma (BAT) in children

Authors: P. Zahradnikova 1; J. Babala 1; Ľ. Sýkora 1; J. Trnka 1; M. Vidiscak 2; P. Sinka 1; L. Fědorová 1

Authors‘ workplace: Paediatric surgery department and Faculty of medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava, National institute of children’s diseases, Bratislava 1; Department of surgery, Faculty of medicine, Slovak Medical University in Bratislava 2

Published in: Rozhl. Chir., 2018, roč. 97, č. 3, s. 139-144.

Category: Case Report

Overview

Minimally invasive techniques have now become standard for the treatment of many surgical conditions in children. There are a few studies that describe the utility of laparoscopy in BAT in children. In this article, we describe the complete laparoscopic surgical treatment of two patients after a single blunt abdominal trauma, both with bowel perforation. In both cases, the perforation was identified and closed, one laparoscopically with an ongoing suture, the second jejune perforation was closed by laparoscopic-assisted techniques. Both patients had an uneventful postoperative recovery. Therapeutic laparoscopic treatment of patients with upper gastrointestinal perforation is feasible. We hypothesize, that diagnostic laparoscopy provides important information for the treatment of children with abdominal trauma and is accompanied by improved diagnostic accuracy, reduction of nontherapeutic laparotomy rates, and a reduction of morbidity. Minimally invasive surgery in children after BAT is suitable for hemodynamic stable patients, could improve pain scores, cosmetic effect, shorter hospital stays, shorter operative times and shorter return to school/activities. However, at any point in the patient’s care, in case the unstable hemodynamic is encountered, exploratory laparotomy is the procedure of choice.

Key words:

miniinvasive surgery − blunt abdominal trauma – laparoscopy − bowel perforationIntroduction

Trauma is the main cause of mortality and morbidity in paediatric patients. Although significant intra-abdominal injury is relatively infrequent, the consequences of missed or delayed diagnosis can be significant. Therefore, an accurate and timely diagnosis and treatment of these injuries is essential. The leading cause of injuries is related to high-energy traumawhich occurs in vehicle road accidents, pedestrian accidents and falls from heights. These causes vary according to age: toddlers suffering from injuries caused by with home-trauma, children sports trauma and teenagers vehicle road accidents. In these cases, a multi-organ involvement must be considered, including not only the abdomen but also a head, a chest, long bones and limbs. To provide optimal treatment to children with blunt abdominal trauma, rapid and appropriate clinical and radiologic diagnostics has to be performed. The need for urgent laparotomy in children with blunt abdominal trauma depends on initial hemodynamic stability and the response to resuscitation. Currently, more than 90% of paediatric patients with intra-abdominal injuries caused by BAT are treated conservatively. Conservative treatment can be carried out only in hemodynamically stable patients with continuous monitoring in the intensive therapy unit for at least 48 hours, and with an experienced multidisciplinary team, that is ready for intervention if necessary. Patients with hemodynamic instability with an insufficient response to resuscitation require immediate laparotomy. Hemodynamic stable patients will undergo clinical and radiological examination. Computed tomography (CT) is the standard procedure for the evaluation of suspected intra-abdominal injury related to blunt abdominal trauma. It allows accurate grading of mainly solid organ injuries, but remains less reliable in the diagnosis of intestinal and pancreatic injuries [1,2].

It is a child who had a blunt abdominal injury with a radiographic evidence of free peritoneal fluid without any evidence of a solid organ injury that poses the greatest diagnostic dilemma. Children with a delay in a diagnosis of a perforated viscous caused by a blunt injury have higher morbidity. A diagnostic laparotomy is a gold standard for the evaluation of these patients. This procedure is not without risks. These include a 20% morbidity rate, 0−5% mortality and a 3% long-term risk for a bowel obstruction [3,4,5]. Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has been used in selected patients for the management of paediatric trauma for over three decades. One of the earliest reports from the 1970s describes peritoneoscopy in 120 patients, including 5 patients under the age of 18. The initial use of laparoscopy in paediatric trauma focused on its ability to reduce the incidence of negative exploratory laparotomy. Carnevale et al. published a report on their experience using laparoscopy to help in the diagnosis of abdominal trauma. Twenty hemodynamic stable patients with evidence of abdominal trauma were evaluated by laparoscopy. In 5 of the patients younger than 18, the results of the laparoscopy demonstrated no injury and they were spared an open laparotomy [6].

Surgical Technique for laparoscopy in BAT

All laparoscopic procedures are performed in patients under general anaesthesia. Cross-matched blood should be available and an operating room personnel prepared for a rapid conversion to an open procedure, if a patient becomes unstable or an unexpected finding is encountered. A nasogastric tube is passed to decompress the stomach and a Foley catheter is inserted into the bladder and coverage with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. The initial exploration is performed with the use of 3 trocars. The peritoneal cavity is accessed via an infraumbilical 5mm port. Two 3mm or 5mm ports (depending on the size of the patient) are placed under direct visualization after a CO2 pneumoperitoneum has been established in the left and right lower quadrant. This position generally allows total inspection of the peritoneal cavity. The fourth 5mm port can be placed in the right side of the abdomen, if necessary. A careful systematic examination of the whole abdominal cavity is conducted. The liver and spleen are carefully inspected and the stomach, duodenum and diaphragm are evaluated. In such a situation, the lesser sac can be opened and explored, although often an additional port-site is required. The whole intestine is inspected, from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal valve, including the colon and rectum. Great care should be taken to examine both the intestine and the supporting mesentery, as unnoticed mesenteric injuries may result in bleeding, bowel ischemia or a late internal hernia. The surgeon must be aware that some areas, such as the third and fourth portions of the duodenum, the pancreas, and the retroperitoneum are difficult to evaluate. Once an injury is identified, the surgeon must decide whether to proceed with a laparoscopic repair or convert to an open laparotomy. Intestinal perforations can be repaired primarily, using intracorporeal suturing techniques or laparoscopic-assisted techniques [7,8,9].

Case report 1

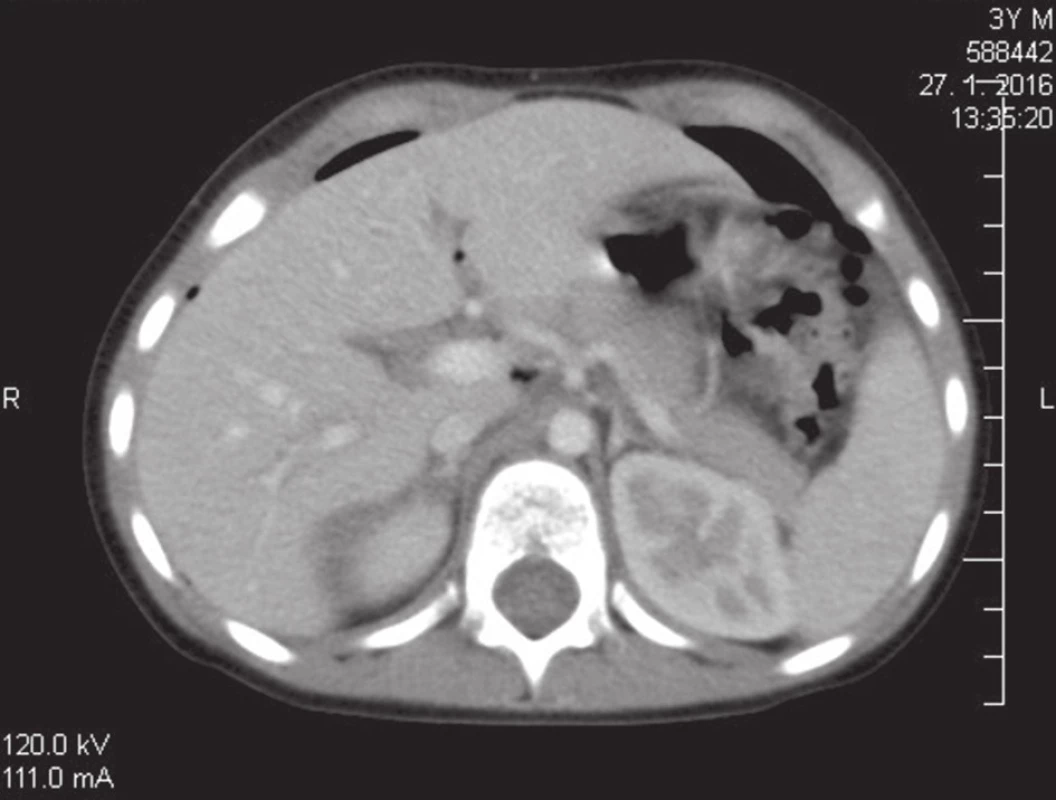

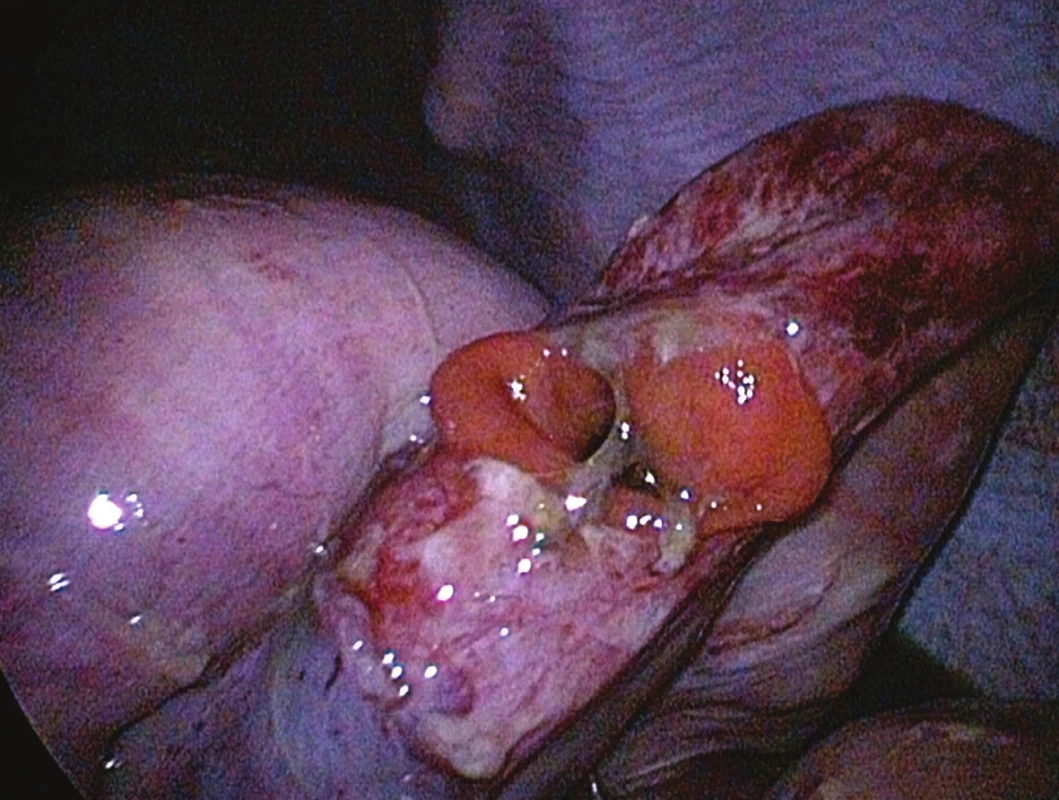

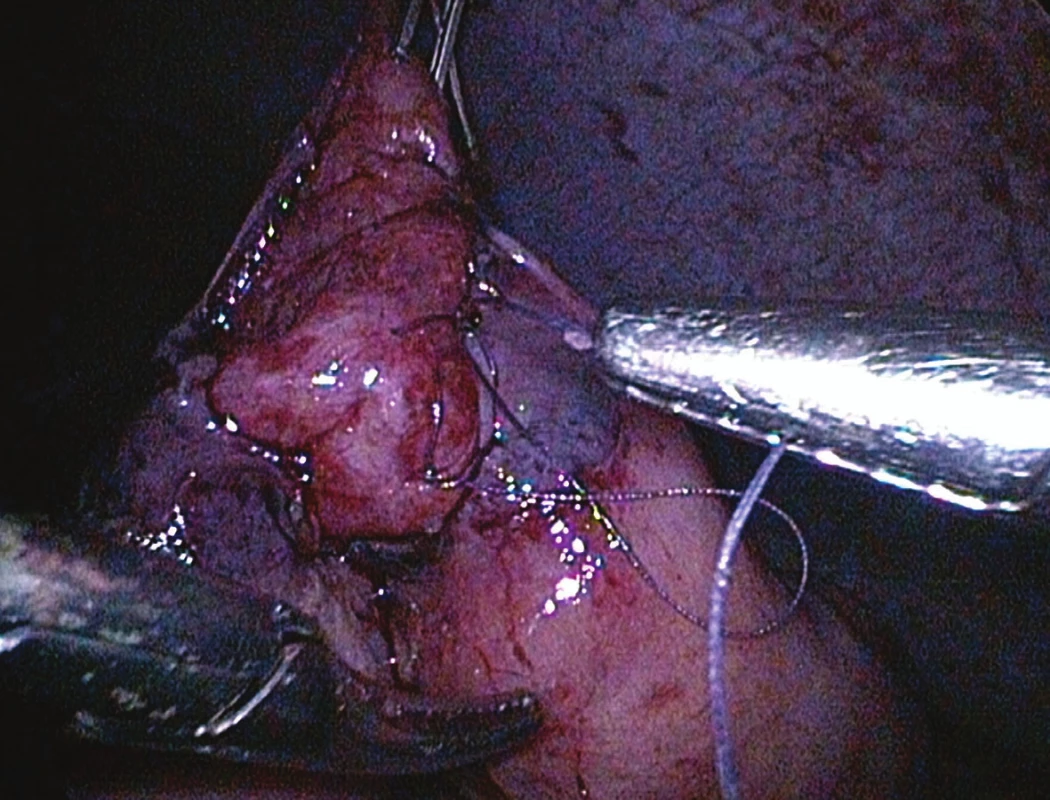

A four-year-old boy with no medical history sustained a road traffic accident; he was fixed with the seat belt. Immediately after the accident he was examined at a nearby first aid department. The patient had a seat belt sign around the umbilicus and a superficial head injury caused by the airbag. He was hemodynamically stable with no neurological complications. Because of the abdominal pain, elevation of hepatic enzymes and the seat belt sign the CT scan was indicated. Extra intestinal air and free intra-peritoneal fluid was seen on the abdominal CT scan, with no solid organ injury (Fig 1). No injury of any solid organs was found. He was referred to our department and was operated 9 hours after the injury. Under general anaesthesia and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic coverage, laparoscopic inspection of the abdomen was started. We used a three port technique; one 5 mm port was placed in the umbilicus for the camera and two 5 mm ports for instrumentation were introduced, one on each side of the abdomen. A large volume of cloudy brown fluid was found with intestine contains. 25 cm of Treitz ligament was a jejune perforation (Fig. 2). The jejune loop was fixed to the anterior abdominal wall and was closed laparoscopically with an ongoing suture (Fig. 3). The whole abdomen was subsequently lavage laparoscopically with warm saline solution and betadine solution. Postoperatively the patient remained in the intensive care unit for 9 nights. 14 days after the surgery, the patient was discharged in a good clinical condition. There were no postoperative problems. During the follow up 1-year period he recovered with no problems.

1. Abdominal CT scan: extra intestinal air and free intra- peritoneal fluid seen on the abdominal CT scan, with no solid organ injury.

2. A large volume of cloudy brown fluid with intestine contains, 25 cm of Treitz ligament the jejune perforation seen during laparoscopy.

3. The jejune loop was fixed to the anterior abdominal wall and was closed by laparoscopy with a ongoing suture.

Case report 2

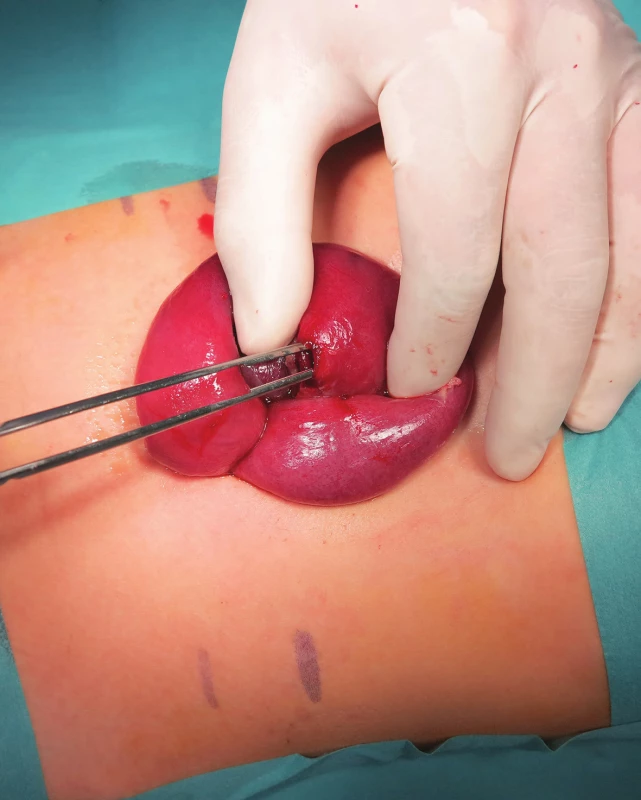

A six-year-old boy with no medical history was examined at a nearby first aid department after a bicycle handlebar injury. After the injury he complained about a stomachache and was vomiting. He was hemodynamically stable. 5 hours after the injury he was admitted to our department. The first diagnostic modality was abdominal ultrasound with finding of free peritoneal fluid, status ileus, haemoperitoneum, oedema of bowel wall and mesentery. Because of USG and a clinical suspicion of ileus we performed an abdominal RTG, which confirmed ileus with typical signs of the obstruction of intestinal passage (Fig. 4). Due to the deterioration of the local abdominal finding we decided for a laparoscopic revision of the abdominal cavity. He was hemodynamically stable. The operation started 9 hours after the injury. Under general anaesthesia and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic coverage, the laparoscopic inspection of the abdomen was started. We used a two-port technique; one 10 mm port was placed in the umbilicus for the camera and 5 mm ports for instrumentation were introduced. A diffuse peritonitis with contamination of intestinal content was seen, a bowel convolution in the left mesogastrium was detected (Fig 5, 6). After the evaluation of the bowel mass we found a jejune perforation in average 8 mm wide. Because of the delay after the abdominal injury, as well as because of the peritonitis we decided for laparoscopic-assisted techniques. By spreading the umbilical incision, we externalized the intestine with a perforation in front of the abdominal cavity; the lesion was closed with an interrupted two layers suture (Fig. 7). Subsequently, the abdomen was intensively lavaged with two litres of warm saline solution. Postoperative parenteral nutrition was started via a central venous line. The nasogastric tube was removed one day after the operation. A complete oral feeding we commenced three days postoperatively. 15 days following the surgery the patient was discharged in a good clinical condition. His further recovery went uneventful, with a 5 months follow up.

4. Abdominal RTG: confirmed ileus with typical signs of the obstruction of the intestinal passage.

Fig. 5, 6: A diffuse peritonitis with contamination of intestinal content and a bowel convolution in the left mesogastrium seen during the laparoscopy.

5. Enlarging of umbilical incision: externalization of the intestine with a perforation in front of the abdominal cavity; the lesion was closed with an interrupted two layers suture.

Discussion

Trauma is the main cause of mortality and morbidity in paediatric patients, and an abdomen is the second most common site of injury. A bowel injury is uncommon after blunt trauma in children. Due to the anatomical central position in the abdominal cavity and fixation due to the ligament of Treitz, lesions of duodenum and proximal portion of jejunum are more frequent [10]. Isolated viscera lesions are usually difficult to diagnose; CT alone cannot be used as a screening tool for a hollow viscous injury because its sensitivity and specificity are approximately 55 and 92%, respectively.

Also, clinical signs and symptoms may be absent, minimal or delayed. US do not usually detect a bowel injury; it can demonstrate indirect signs, such as free fluid between bowel loops [11]. All parts of the abdominal intestine can be affected and lesions are quite variable in their clinical presentation. Small intestinal injuries repesent more than a half of all blunt intestinal injuries, with an equal involvement of the jejunum and ileum [12]. The second most frequent location of injury is the colon; several studies show that the left colon is more commonly injured than the transverse or the right colon [13,14]. Duodenal lesions representing above 10% of the abdominal injuries and are often associated with pancreatic trauma. Blunt trauma injuries of the rectum and stomach are even less frequent, representing only 5% of the total. There are several types of intestinal and mesenteric injuries. The most common intestinal lesions are serous or seromuscular tears. Next comes a full-thickness perforation, which can be a punctate blowout or a full-thickness tear of the intestinal wall. In addition, there are mural hematomas and extensive seromuscular lesions with de-gloving of the intestine. Late post-traumatic intestinal strictures may occur resulting in a bowel obstruction, probably due to localized segmental ischemia which progresses to a fibrotic stricture [15]. Mesenteric injuries range from bruising to hematoma and frank bleeding through the torn peritoneal envelope. If bleeding is active, a hematoma may rapidly enlarge, distending the entire mesenteric root. If the peritoneum overlying the mesentery is torn, it results in a haemoperitoneum. Mesenteric disinsertion may occur with the avulsion of the proximal or distal mesenteric root; this may cause intestinal perforation along the mesenteric surface of the bowel and localized devascularisation of an intestinal segment resulting in ischemia and a secondary perforation [13]. Isolated viscera lesions are usually difficult to diagnose. The suspicion of a hollow viscous injury comes from clinic data, type of a trauma, a possible presence of a superficial abdominal wall bruising and from a diagnostic imaging. Paediatric patients may have a delayed presentation to the hospital after an abdominal trauma. Subtle injuries in children are often not witnessed by an adult, such as a fall onto a bicycle handlebar or an unreported child abuse, and may result in a significant delay in diagnosis and management. For hemodynamically stable trauma patients, CT plays an essential role. Signs of an intestinal wall injury include: discontinuity of the intestinal wall, thickening of the bowel wall, and the enhancement of the intestinal wall defect after an intravenous (IV) contrast injection (increased or decreased enhancement). Images suggesting a mesenteric injury include: IV contrast extravasation (blush) or an abrupt discontinuation of opacification along a vascular branch, an infiltration of mesenteric fat (blurring, hyperdense and honeycombed appearance), a hematoma, and a string of pearls appearance of mesenteric vessels. Other signs include: pneumoperitoneum (a few air bubbles or widespread free air), free peritoneal or retroperitoneal fluid (often quantified and described depending on whether it is associated with a solid organ injury), and an injury of muscular layers of the abdominal wall and subcutaneous tissue. The need for an urgent surgery is obvious when one of the following clinical or CT signs is present: hemodynamic instability, signs of frank peritonitis, loss of intestinal continuity, pneumoperitoneum, contrast extravasation and mesenteric ischemia. In the absence of these signs, the decision of whether or not to operate is difficult [13]. Even in the current era of CT scanners, as many as 21% of patients with bowel or mesenteric injuries may initially have negative studies [16]. CT findings of “softer” signs of intestinal injuries, including the bowel wall thickening, free intra-peritoneal fluid without an evidence of a solid organ injury, and mesenteric stranding often lead to a diagnostic dilemma and a decision of whether to perform a surgical exploration or not. In the past, a formal exploratory laparotomy would be performed. Unfortunately, a significant number of explorations fail to reveal significant intra-abdominal pathology, and the procedure carries a relatively high degree of morbidity [17]. A diagnostic laparoscopy has proven to be a useful modality in these situations. As a diagnostic tool, the rate of a missed injury with laparoscopy in the adult literature is reported at 1%–3% [18,19]. The paediatric trauma literature reports almost 0% missed injury rate [20]. In the largest published series to date, Feliz et al. performed a 5-year review of a paediatric level 1 trauma centre database. In more than 7,000 admissions, 113 children (with both blunt and penetrating mechanisms) required an operative exploration [21]. In 32 patients undergoing an initial diagnostic laparoscopy, 9 (28%) had no injury observed and another 3 had an injury that required no further therapy. Six of the 32 patients had their injury repaired laparoscopically. Fabian et al reviewed their experience of 182 patients who underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy to confirm a peritoneal violation after sustaining penetrating abdominal trauma. In their study, an exploratory laparotomy was performed in all patients with a documented peritoneal violation. Overall, 55% of patients avoided an unnecessary laparotomy. Of the remaining patients who underwent laparotomy, 67% of patients with a peritoneal violation required a therapeutic intervention [22]. An extensive laparoscopic expertise is mandatory, to be able to treat patients with upper intestinal perforations [23]. The closure of bruised intestinal tears requires sufficient skills in intra-corporeal laparoscopic suturing. Localizing the perforation and ruling out other injuries requires experience in a surgical exploration of the anatomical area of interest. Based on the skills required, a laparoscopic approach is safe only for experienced laparoscopic surgeons. Also the laparoscopic approach should be restricted to thermodynamically stable patients. According to the Evidence-based guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery Laparoscopy is suitable for suspected penetrating trauma. A diagnostic laparoscopy is a useful tool to assess the integrity of the peritoneum and avoid a nontherapeutic laparotomy in stable patients (GoRB: grade of recommendation B). Stable patients with blunt abdominal trauma may undergo a diagnostic laparoscopy to exclude a relevant injury (GoRC: grade of recommendation C) [24]. A conversion to open surgery should be considered at every step of the procedure. With both of our patients we found obvious abdominal contamination as the perforation had already existed for several hours. We rinsed the abdomen with warm saline solution. Cultures taken from the abdomen after a prophylactic intravenous antimicrobial therapy remained negative. Sheer laparoscopic cleaning of the abdomen in purulent peritonitis is feasible as shown in multiple series of gastric or colorectal perforation. Therefore we believe that finding a perforation during the laparoscopy is not an absolute indication to convert to laparotomy, provided that the lesion can be managed adequately.

Conclusion

It is important to provide optimal treatment for children with blunt abdominal trauma and consider many factors. Laparoscopic exploration and either primary or assisted repair of intra-abdominal injuries in hemodynamically stable paediatric patients who sustain focal abdominal trauma is an appropriate surgical option. On the other side, the role of laparotomy is still irreplaceable in this century, in hemodynamically unstable paediatric patients and in patients with multi-organ injuries it is essential.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have not conflict of interest in connection with the emergence of and that the article was not published in any other journal.

MUDr. Petra Zahradníková

KDCH a LFUK NÚDCH Bratislava

Limbová 1,

833 40 Bratislava,

e-mail: pezahradnikova@gmail.com

Sources

1. Nastanski F, Cohen A, Lush SP, et al. The role of oral contrast administration immediately prior to computed tomographic evaluation of the blunt trauma victim. Injury 2001;32 : 545−9.

2. Sherk JP, Oakes DD. Intestinal injuries missed by computed tomography. J Trauma 1990; 30 : 1−5.

3. Ross S, Dragon G, O’Malley K, et al. Morbidity of negative celiotomy in trauma. Injury 1995;26 : 393−4.

4. Shih C, Wen S, Ko J, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma: prospective study using diagnostic algorithms to minimize nontherapeutic laparotomy. World J Surg 1999;23 : 265−70.

5. Carrillo H, Spain D, Wohltmann C, et al. Interventional techniques are useful adjuncts in nonoperative management of hepatic injuries. JTrauma 1999;46 : 619−24.

6. Carnevale N, Baron N, Delany H, et al. Peritoneoscopy as an aid in the diagnosis of abdominal trauma: a preliminary report. J Trauma 1977;7 : 634−41.

7. Feliz A, Shultz B, McKenna C, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy in pediatric abdominal trauma. J Pediatr Surg 2006;41 : 72−7.

8. Marwan A, Harmon C, Georgeson K, et al. Use of laparoscopy in the management of paediatric abdominal trauma. J Trauma 2010;3 : 215−8.

9. Streck C, Lobe T, Pietsch J, et al. Laparoscopic repair of traumatic bowel injury in children. J Pediatr Surg 2006;41 : 1864−9.

10. Carbon R, Baar S, Waldschmidt J, et al. Innovative minimally invasive paediatric surgery is of therapeutic value for splenic injury. J Paediatr Surg 2002;37 : 1146−50.

11. Madsen H. Ultrasound contrasts: the most important innovation in ultrasound in recent decades. Acta Radiol 2016;49 : 247−8.

12. Miele V, Piccolo C, Trinci M, et al. Diagnostic imaging of blunt abdominal trauma in pediatric patients. Radiol med 2016;121 : 409−30.

13. Bège T, Brunet C, Berdah S, et al. Hollow viscus injury due to blunt trauma: A review. Journal of Visceral Surgery. 2016; 153 : 61−8.

14. Alsayali D, Atkin C, Winnett J, et al. Management of blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries: experience at the Alfred hospital. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2009;35 : 482−8.

15. Hughes T, Elton C, et al. Intra-abdominal gastrointestinal tract injuries following blunt trauma: the experience of an Australian trauma centre. Injury 2002;33 : 617−26.

16. Lien G, Mori M, Enjoji M, et al. Delayed posttraumatic ischemic stricture of the small intestine. A clinicopathologic study of four cases. ActaPatholJpn 1987;37 : 1367−9.

17. Ekeh A, Saxe J, Walusimbi M, et al. Diagnosis of blunt intestinal and mesenteric injury in the era of multidetector CT technology—are results better? J Trauma 2008;65 : 354−9.

18. Ross S, Dragon G, O’Malley, et al. Morbidity of negative celiotomy in trauma. Injury 1995;26 : 393−4.

19. Fabian TC, Croce MA, Stewart RM, et al. A prospective analysis of diagnostic laparoscopy in trauma. Ann Surg 1993;217 : 557−64.

20. Ball CG, Karmali S, Rajani RR, et al. Laparoscopy in trauma: an evolution in progress. Injury 2009;40 : 7–10.

21. O’Malley E, Boyle E, O’Callaghan A, et al. Role of laparoscopy in penetrating abdominal trauma: A systematic review. World J Surg 2013;7 : 113–22.

22. Villavicencio RT, Aucar JA, et al. Analysis of laparoscopy in trauma. J Am Coll Surg 1999;189 : 11–20.

23. Marwan A, Harmon C, Georgeson K, et al. Use of laparoscopy in the management of pediatric abdominal trauma. J Trauma 2010; 69 : 761−94.

24. Alemayehu H, Clifton M, Santore M, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for pediatric trauma - a multicenter review. Journal of laparoendoscopic&advanced surgical techniques. 2015; 25 : 243−7.

Labels

Surgery Orthopaedics Trauma surgery

Article was published inPerspectives in Surgery

2018 Issue 3-

All articles in this issue

- Prediction of bowel damage in patients with gastroschisis

- Multidisciplinary approach to surgical disorders of the pancreas in children

- Open versus laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis in children

- Supracondylar fracture of the humerus in childhood

- Laparoscopy at the pediatric surgery department for a five-year period

- Hirschsprung’s disease in adults − two case reports and review of the literature

- Laparoscopic treatment of bowel perforation after blunt abdominal trauma (BAT) in children

- Perspectives in Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Supracondylar fracture of the humerus in childhood

- Hirschsprung’s disease in adults − two case reports and review of the literature

- Open versus laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis in children

- Laparoscopy at the pediatric surgery department for a five-year period

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career