-

Medical journals

- Career

Strategies of treatment of chest wall tumors and our experience

Authors: J. Chudacek 1; T. Bohanes 1; M. Szkorupa 1; J. Klein 1; M. Stasek 1; B. Zalesak 2; D. Stehlik 2; F. Ctvrtlík 3; C. Neoral 1

Authors‘ workplace: The 1st Dep. of Surgery, Palacký University Teaching Hospital Olomouc Department Head: prof. C. Neoral, M. D., CSc. 1; Department of Plastic Surgery, Palacký University Teaching Hospital Olomouc Department Head: MUDr. B. Zálešák, Ph. D 2; Department of Radiology, Palacký University Teaching Hospital Olomouc Department Head: prof. MUDr. M. Heřman, Ph. D 3

Published in: Rozhl. Chir., 2015, roč. 94, č. 1, s. 17-23.

Category: Original articles

Overview

Introduction:

The only curative treatment of tumors of the chest wall (primary or secondary),despite all the progress in oncological therapy, is a surgical radical resection. The goal of the paper is the identification of a complication occurring after chest wall resections for a tumor (evaluation of morbidity and mortality). Furthermore, the tumor type and employed reconstruction method were analyzed.Methods:

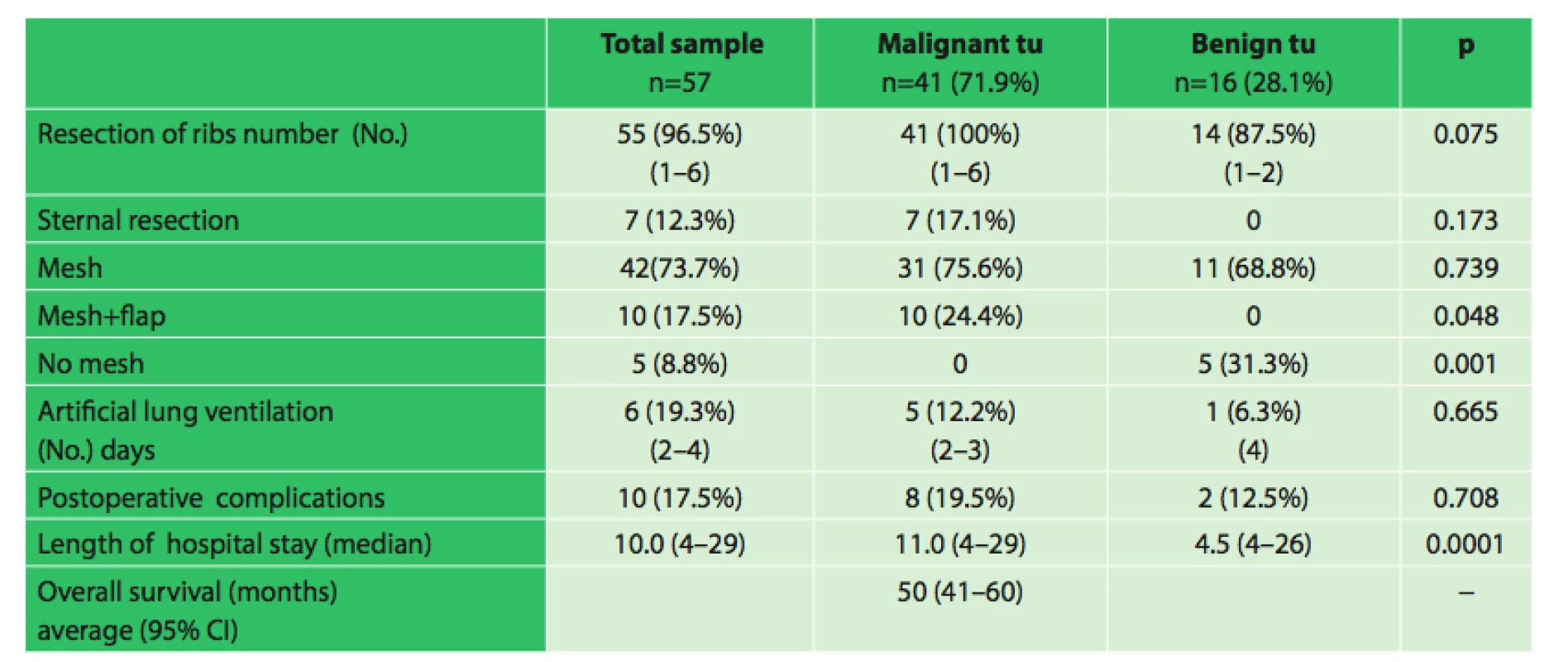

A group of patients who underwent resection of the chest wall for primary or secondary tumors at the 1st Dept. Of Surgery, University Hospital Olomouc, was retrospectively analyzed. Age, diagnosis, procedure, histopathology of the tumor, preoperative and postoperative oncological treatment, preoperative co-morbidities, postoperative complications, the use of artificial lung ventilation and recurrences were recorded for all patients.Results:

57 patients aged 16 to 86 years underwent a chest wall resection, 51% for a primary tumor and 49% for a secondary tumor. Resection of at least one rib or partial resections of the sternum were performed in every patient. Reconstruction with a mesh was employed in 22 patients; in 10 patients the mesh was covered with a muscle flap. Postoperative complications occurred in 10 patients (17.5%).Conclusion:

It is necessary to follow the basic principles of treatment of chest wall tumors; therefore surgery of these tumors should be concentrated to specialized centers. Always before surgery, diagnosis should be established by means of a biopsy and generalization of the disease should be excluded, ideally using PET/CT. Most important for successful treatment is experience and interdisciplinary cooperation of the team. This results in a low mortality and morbidity rate, which was confirmed by our results.Keywords:

chest wall tumors − chest reconstruction − sternum resection – treatment of chest wall tumors − chondromaIntroduction

Tumors of the chest wall belong to a rare group of neoplasms. Roughly half of them are malignant, mostly metastases or tumors growing directly from the adjacent structures, i.e. lung, mediastinal or breast cancer. The most extensive sample of 317 patients of over 20 years, who had undergone chest wall resection for malignant tumors, is described by a team of authors from Philadelphia. The sample represented primary lung/breast carcinoma in 51% (163 patients) and metastatic tumors in 22% (71), while primary malignant tumors of the chest wall were represented only by 26% (83 patients) [1]. Another large study included 262 patients with primary lung cancer in 38% (99 patients), breast carcinoma in 10% (26 patients) and sarcoma in 29% (95 patients) [2]. These data suggest that primary malignant tumors of the chest wall are uncommon compared with secondary ones. Benign tumors, comprising the second half of the tumors in the chest wall, are represented by 21 to 67% in various studies [3,17,20].

Primary tumors of the chest wall may occur in any part of the wall and cover a wide range of benign and malignant mesenchymal neoplasms with the occasional occurrence of hemoblastomas. They can be asymptomatic for a long time, especially in the initial stages of the disease. The first manifestation may be only a gradually growing palpable mass. One of the first specific symptoms may be pain, but syndromes associated with local tumor growth, such as the superior vena cava syndrome, may also occur. Diagnosis is very difficult if no palpable tumor is found during clinical examination. The most important steps in the treatment of tumors of the chest wall are exact histological verification and accurate identification of the tumor location and extent. Another requirement is to avoid generalization of the disease; PET/CT examinations make a great contribution in this regard. However, the only curative treatment modality remains radical surgical resection despite the major advances in oncological protocols.1. Characteristics of the group of patients.

Objective

The aim of the study was to determine the optimal surgical procedure for the treatment of tumors of the chest wall in relation to complication occurrence. The histological tumor type, length of hospitalization, age, perioperative mortality and morbidity were studied in all patients. Whether the use of a muscle flap with a mesh in the reconstruction of the chest wall would reduce the number of complications compared to the use of a mesh without flap was also assessed. Another equally important endpoint was the difference in survival between the particular malignant tumor groups (primary versus secondary tumors of the chest wall, tumors infiltrating the chest walls, growing from adjacent structures).

Methods

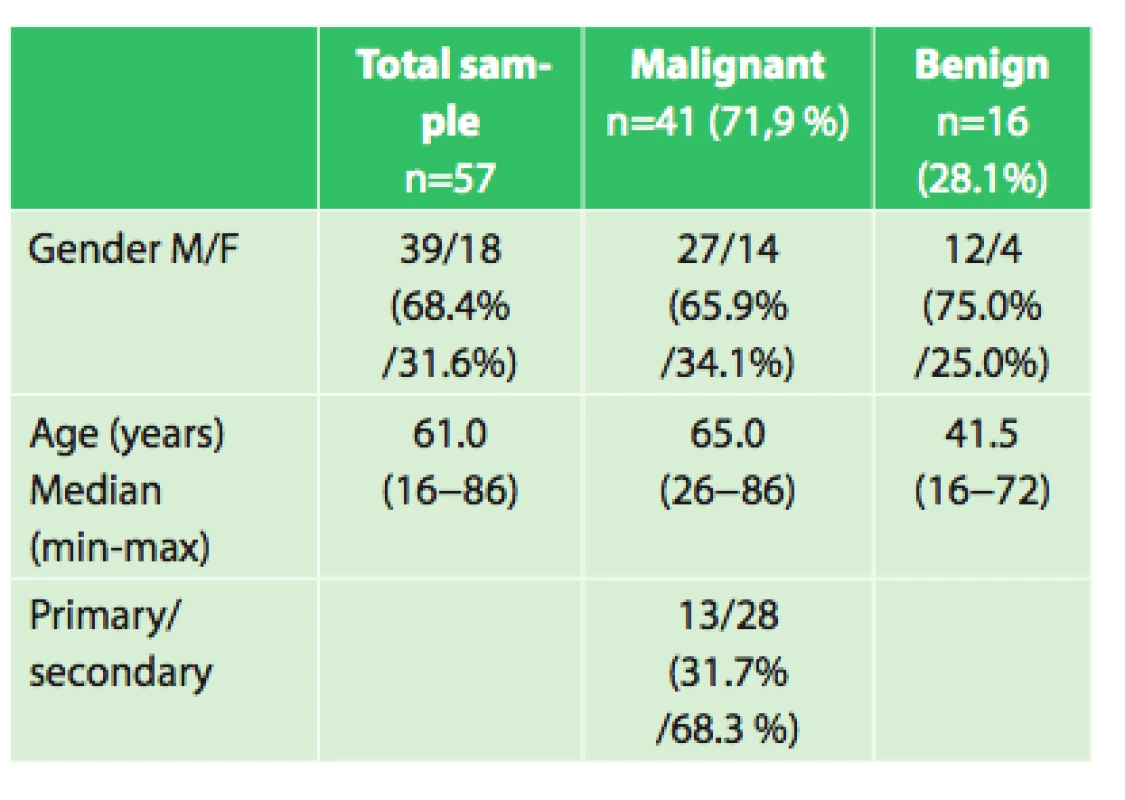

In the period 2006−2012, 57 patients underwent a chest wall resection for primary or secondary tumor (metastasis to the chest wall and lung tumors infiltrating the chest wall) at the First Department of Surgery, University Hospital Olomouc. The following parameters were assessed in these patients: histopathological tumor type, gender, age, number of resected ribs or extent of the sternum resection, type of reconstruction of the chest wall, length of mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, perioperative morbidity and mortality and length of survival of patients with malignant tumors. Data were analyzed using statistical software SPSS version 15 (USA). Comparison of qualitative parameters was made using Fisher’s exact test. Quantitative parameters were compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test and post hoc Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The chosen significance level was 0.05.

Fig. 1: PET/CT scan- tumor of the sternum

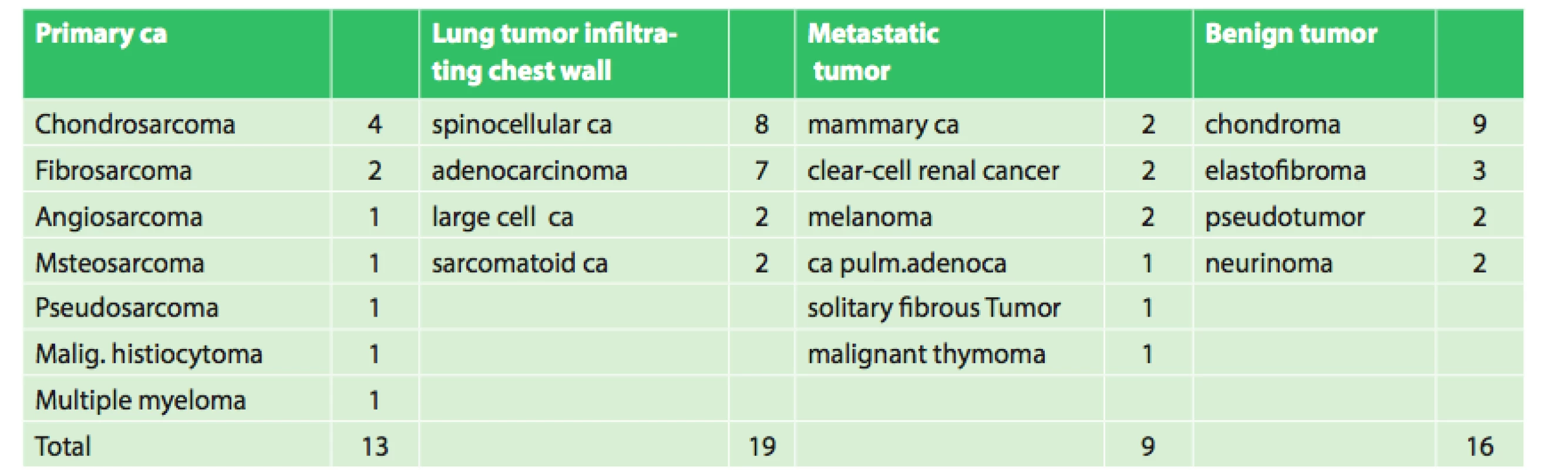

The group included 19 women and 38 men aged 16−86 years, median age was 61 years. The patients were indicated for surgery on the basis of pre-operative histological verification or needle biopsy. There were a total of 16 benign and 41 malignant tumors, of which 13 were primary chest wall carcinomas, 19 lung cancers infiltrating the chest wall and 9 metastatic cancers.

In all patients, CT of the chest wall, lung and mediastinum was performed, and, since 2009, positron emission tomography (PET/CT) was routinely carried out. For tumors with suspected ingrowth into the spinal canal, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used.

Each patient was discussed by an indication board, which also included a plastic surgeon. For resection of the chest wall the oncosurgical operating guidelines for primary tumors of the chest wall were adhered to, i.e. 4 cm safety resection margins and resection of one rib above and one rib below the tumor. In the case of benign tumors, the safety margins of 2 cm were implemented. For secondary tumors, the resection margins were again 2 cm, but included complete resection of one rib above and one below the tumor. In lung cancer infiltrating the chest wall, thoracotomy was performed initially with a subsequent revision of the pleural cavity in order to check for operability of the lung cancer, followed by anatomic lung resection (mostly lobectomy), accompanied by a radical mediastinal lymphadenectomy. The number of resected ribs was between 1 and 6. A sternal resection was performed in 7 patients, but always only as a partial one. In 5 patients, the small defect in the chest wall after resection was closed with sutures of the pericostal muscle flaps to the adjacent ribs. In all other cases of chest wall resection (52 patients), it was necessary to use polypropylene mesh (non-rigid replacement), which was fixed with prolene stitches to the adjacent ribs. Two patients underwent a resection of the sternum and ribs. In cases of the resection of the sternum, the bone cement sandwich method was employed, in which cement was applied between two sheets of a polypropylene mesh and shaped for the exact replacement of the defect and fixed with titanium plates. This is a rigid type of sterna fixation. No other reconstruction techniques were used in our group. In 10 cases, the plastic surgeon had to repair the soft tissue using flap transposition, in 8 cases using musculocutaneous flap of m. latissimus dorsi and twice using free flap transfer of the transverse rectus abdominis muscle.

Results

The most common primary malignant tumor was chondrosarcoma and, in the cases of a benign tumor, they were chondromas. Similar findings were described by Italian authors in 2014 [4]. The most frequent secondary cancers were metastases of breast and kidney cancer.

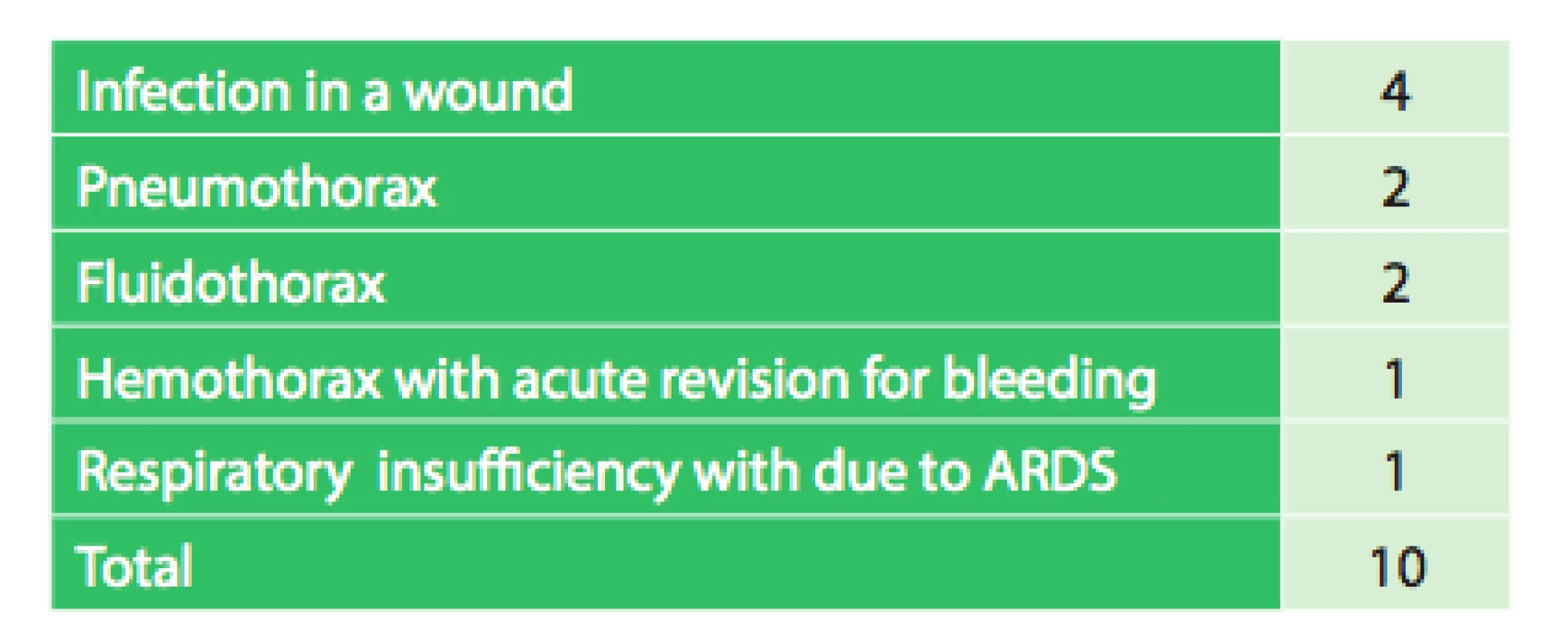

The length of hospital stay ranged between 4−29 days with a median of 10 days. In the early postoperative period, one death due to ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome) was observed. On the fifth postoperative day, it was necessary to revise one patient for hemothorax. Infection in the surgical wound occurred in 4 patients. In one patient on day 42 after surgery, it was necessary to remove the mesh due to infection, the patient subsequently healed with no complications. Other complications were fluidothorax twice and pneumothorax twice, one of which required thoracic redrainage. Overall, there were 10 complications (17.5%).

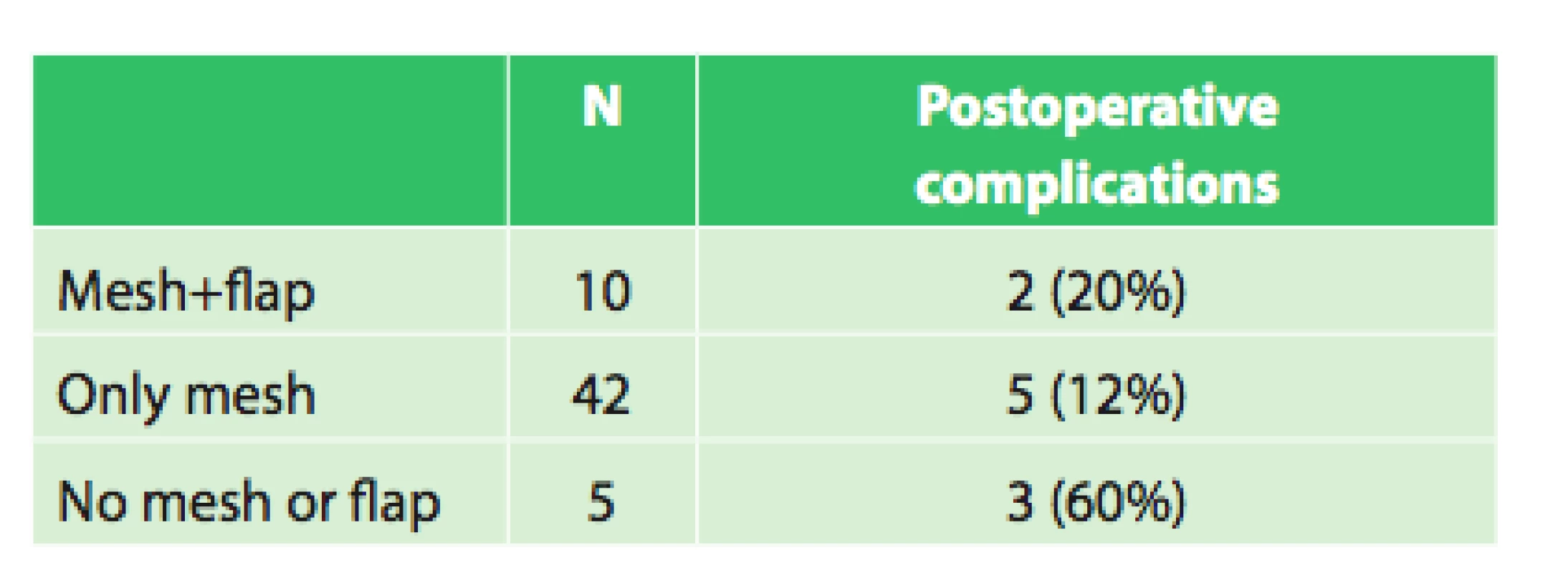

No evidence of significant correlation between the incidence of postoperative complications and the use of a separate mesh or a mesh with muscle flap (p = 0.608) was found. There was also no significantly higher incidence of postoperative complications without the use of a mesh and flap (p = 0.033) in our group.

4. Postoperative complications in relation to the use of mesh and flap

5. Overall summary

Note: 95%CI ... 95%-CI reliability interval There was no significant correlation between the incidence of postoperative complications and the number of resected ribs (p = 0.453) or between the postoperative complications and artificial ventilation (p = 0.281).

In malignant tumors, the combination of a mesh and flap was used significantly more often (24% vs. 0% p = 0.048). In benign tumors, a mesh was used significantly more often (31% vs. 0%, p = 0.001). Length of hospital stay was significantly longer in malignant tumors (median 11 vs. 4.5 days, p = 0.0001).In cases of lung tumors infiltrating the chest wall we demonstrated a significantly lower percentage of survival than in primary malignant tumors (26% vs. 85%, p = 0.010 Fisher’s exact test with Bonferroni correction).

The average survival of patients with primary malignant tumors was 69 months (95% CI, 54−85 months), tumors infiltrating the chest wall 45 months (95% CI, 34−56 months), and metastatic tumors of the chest wall 45 months (95% CI: 27−62 months).Kaplan-Meier analysis with log rank test showed no significant difference in survival between patients with different types of findings (p = 0.168).

Discussion

Chest wall tumors represent a wide range of tumor types with different histopathology. Their treatment should be primarily surgical, as confirmed by our work. For primary malignant tumors the recommended principles should be followed: it is necessary to maintain safety margins of 4 cm, together with the resection of one unaffected rib above and below the tumor [7,8,9]. This radical procedure can result in 90% five-year survival even in highly malignant chondrosarcomas [6]. However, the histopathologic distinction of chondromas from chondrosarcomas is difficult. For chondromas, it is therefore necessary to resect more radically than in other benign tumors, partly because of the difficulty of distinguishing from malignant chondrosarcoma and partly because of its possible malignant transformation [10]. If the chest wall tumor is located near the spinal column, it may be necessary to cooperate with a surgeon trained in spinal surgery. In case of a suspicion of spinal column involvement, it is necessary to perform magnetic resonance imaging, and radical surgical therapy is only possible if there are no signs of spinal column involvement. Mobilization of the tumor through a posterior approach is the first phase of the procedure; subsequently, a thoracic surgeon completes the radical resection of chest wall.

Secondary malignancies which are a topic of particular discussion are metastases to the chest wall. Because these metastases are often a sign of dissemination of the malignant disease, radical resection is permissible only if three conditions are met: a) it is only an isolated metastasis, b) it is possible to perform complete resection with negative resection margins, c) the locoregional disease is under control. If these conditions are met and resection is performed, according to the available literature, the five-year survival rates range from 20 to 38% [1,11]. These results, however, are relatively favorable. Palliative resection of the chest wall in generalized malignant disease is justified only in a limited number of cases, such as ulceration or bleeding from the chest wall. No extensive work that discusses this indication has been published to date in international literature; there are only a few case reports [7]. Each case should be considered individually according to the overall status of the patient.

Another issue is chest infiltration in lung cancer, which is reported in 2−8% [12]. The surgery is begun with verification of operability of the tumor through a thoracotomy or videoassisted thoracoscopy. If it is decided to perform a resection, chest wall resection follows with safety margins of at least 2 cm from the tumor and resection of the ribs above and below the tumor. The following phase is anatomic pulmonary resection and removal of the tumor, which is resected en-bloc with the chest wall, and a systematic lymphadenectomy is performed. Finally, if the reconstruction of the chest wall is necessary, repair of the defect follows. Lung cancer infiltrating the chest wall requires resection of at least three ribs [13]. Five-year survival for these patients is not dependent on the extent of resection of the chest wall, but on the clinical stage of the lung cancer [14]. Even if there is compliance with performing a radical resection of positive nodes, the five-year survival period is unfortunately below 10% [13]. Histological differentiation and depth of invasion of lung cancer to the chest wall and parietal pleura are independent prognostic factors of survival [15,16].

1. Kaplan-Meier analysis of patient group

Reconstruction of chest wall defects should be divided into skeletal reconstruction and reconstruction of the soft tissue. In earlier times, reconstruction of the skeleton of the chest wall used animal materials, for example the pericardium or the fascia of the tensor fasciae latae muscle. In 1940, a large defect of the chest wall was reconstructed for the first time by means of autologous tensor fasciae latae muscle. 40 years later synthetic non-rigid material was used for the first time [17]. In practice, it is not necessary to repair the chest wall when the defect is covered by the shoulder bone and dorsal muscles. In other parts of the chest wall, it is necessary to perform some reconstruction.

The reconstruction material can be divided into rigid and non-rigid ones. The rigid materialsmay include plates made of methylmetacrylate or titanium, or, as in our case of a partial resection of the sternum, the bone cement sandwich method, in which cement is put between two meshes. These are suitable especially in the front and sides of the chest wall, where it is desirable to retain its shape.

Autologous bone grafts made from the iliac or other bones may serve as a possible alternative. The use of cadaverous ribs from a donor was also reported [18]. The most commonly used non-rigid material for reparing chest wall defects are meshes. They can be non-absorbable, made of Prolene, or also absorbable. Fibroblasts penetrate the mesh and a firm fibrous layer arises at the site of the mesh, which sufficiently stiffens the chest wall.

Fig. 2: Use of sandwich method after sternum resection

Fig. 3: Chest wall reconstruction using the mesh

The disadvantage of synthetic materials is the risk of wound infection where making it sterile again is difficult and not always successful. Sometimes it is even necessary to remove the mesh. In our group it was necessary only once, when it was the only option to treat the recurrent fistula during reconstruction of the chest wall. It was necessary to extract the mesh 42 days after the primary surgery. The resulting chest wall defect did not need any subsequent reconstruction, because the mesh bed was turned into a solid fibrous layer.

Reconstruction of the soft tissues of the chest was first performed by Tansini in 1906[19], which used a flap of the latissimus dorsi muscle. In the beginning this was a two-stage operation: the first phase included resection and reconstruction of the chest wall and the second phase consisted of reconstruction of soft tissue. Several studies confirmed unequivocally that the best results can be achieved through careful resection of the chest wall with an immediate reconstruction [20,21]. The main advantage of the soft tissue reconstruction after the resection is reducing the risk of infection and accelerating engraftment. Initially various modifications of rotated flaps of the latissimus dorsi muscle or the pectoral muscle were used. Over time, it became clear that the method of choice is a free musculocutaneous flap depending on the location of the defect in the chest wall and the possibility of reconstruction of the blood supply needed to feed the flap. However, this phase of the operation should be performed by a plastic surgeon who is experienced in microsurgical techniques and the resulting cosmetic effects of the operation are impressive, as evidenced by our group of patients.

Fig. 4: Final effect after soft tissue reconstruction

The incidence of postoperative complications after resection of the thoracic wall according to the available literature ranges between 21.6% [22] and 36% [14]. Our results are even better – 17.5%, i.e. out of 57 patients, there were only 10 complications.

Oncological therapy as treatment of this large group of different types of tumors is not a matter of discussion of this article, because it would require several other chapters.

Conclusion

Tumors of the chest wall are rarely diagnosed due to their low incidence. It is essential to follow the basic principles of treatment. For this reason, surgery of these tumors should be concentrated in centers that are experienced with the treatment of these tumors. Prior to surgery, these tumors should first be diagnosed via biopsy and generalization of disease should be excluded, preferably using PET/CT. Secondary tumor metastases of the chest wall are indicated for resection if the patient is able to undergo surgery, with the exception of patients with generalization of the underlying disease,. In conclusion, most important for successful treatment of tumors of the chest wall are the experience and interdisciplinary cooperation of the entire team involved in the treatment of these tumors, and result in a low mortality and morbidity as it was shown in our group of patients.

Ethics

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have not conflict of interest in connection with the emergence of and that the article was not published in any other journal.

MUDr. Josef Chudáček

Divišova 8

796 01, Prostějov

e-mail: josef.chudacek@seznam.cz

Sources

1. Martini N, McCormack PM, Bains MS. Chest wall tumors: clinical results of treatment. In.: Grillo HC, Eschapasse H, eds. International trends in general Thoracic Surgery. Vol 2. Major challenges. Philadelphia, Saunders 1987 : 285.

2. Weyant MJ, Bains MS, Venkatraman E, Downey RJ, Park BJ, et al. Results of chest wall resection and reconstruction with and without rigid prosthesis. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;81 : 279−85.

3. Athanassiadi K, Kalavrouziotis G, Rondogianni D, Loutsidis A, Hatzimichalis A, et al. Primary Chets wall tumors: early and long-term results of surgica treatment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;19 : 589−93.

4. Weber DJ, Coleman JJ, Kesler KA. Refractory bleeding from a chest wall sarcoma: a rare indication for palliative resection. J Cardiothorac Surg [serial on the Internet]. 2013;8 : 82. Available from: http://www.cardiothoracicsurgery.org/content/8/1/82.

5. Hsu PK, Hsu HS, Lee HC, Hsieh CC, Wu YC, et al. Management of primary chest wall tumors: 14 years clinical experience. J Chin Med Assoc 2006;69 : 377−82.

6. Marulli G, Duranti L, Cardillo G, Luzzi L, Carbone L, et al. Primary chest wall chondrosarcomas: results of surgical resection and analysis of prognostic factors. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45 : 194−201.

7. Jedlička V, Vlček P, Veselý J, Veverková L, Čapov I, et al. Resekce a rekonstrukce hrudní stěny pro primární či metastatické nádorové onemocnění. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 2011;78 : 361−6.

8. Gonfiotti A, Santini PF, Campanacci D, Innocenti M, Ferrarello S, et al. Malignant primary chest-wall tumours: techniques of reconstruction and survival. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg 2010;38 : 39−45.

9. Sylvin EA, Kucharczuk JC. Chest wall mass. ACS Surgery [serial on the Internet] 2013. Available from: http://acssurgery.com/acssurgery/secured/payPerAdd.action?chapterId=part04_ch03.

10. Shah AA, D´Amico TA. Primary chest wall tumors. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210 : 360−366.

11. Pfannschmidt J, Geisbüsch P, Muley T, Hoffmann H, Dienemann H. Surgical resection of secondary chest wall tumors. Thorac Cardiovascular Surg 2005;53 : 234−9.

12. Incarbone M, Pastorino U. Surgical treatment of chest wall tumors. World J Surg 2001;25 : 218−30.

13. Klein J. Chirurgie karcinomu plic. 1. vyd. Praha, Grada Publishing 2006.

14. Aghajanzadeh M, Alavy A, Taskindos M, Pourrasouly Z, Aghajanzadeh G, et al. Results of chest wall resection and reconstruction in 162 patients with benign and malignant chest wall disease. J Thorac Dis 2010;2 : 81–5.

15. Chapelier A, Fadel E, Macchiarini P. Factors affecting long-term survival after en-bloc resection of lung cancer invading the chest wall. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2000;8 : 513−8.

16. Piehler JM, Pairolero PC, Weiland LH, Offord KP, Payne WS, et al. Bronchogenic carcinoma with chest wall invasion: factors affecting survival folowing en bloc resection. Ann Thorac Surg 1982, 34 : 684−91.

17. Deschamps C, Tirnaksiz BM, Darbandi R. Early and long-term results of prosthetic chest wall reconstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;117 : 588−92.

18. Aranda JL, Varela G, Benito P, Juan A. Donor cryopreserved rib allografts for chest wall reconstruction. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2008;7 : 858−60.

19. Tansini I. Sopra il mio nuovo processo di amputazione della mammella. Gazz Med Ital Torino 1906;57 : 141−3.

20. McCormack P, Bains MS, Beattie EJ Jr, Martini N. New trends in skeletal reconstruction after resection of chest wall tumors. Ann Thorac Surg 1981;31 : 45−52.

21. Larson DL, McMuertery MJ, Howe HJ, Irish CE. Major chest wall reconstruction after chest wall irradiation. Cancer 1982;49 : 1286−91.

22. van Geel AN, Vouters WJM, Lans TE, et al. Chest wall resection for adult soft tissue sarcomas and chondrosarcomas: Analysis of prognostic factors. Worl J Surg 2011;35 : 63−9.

Labels

Surgery Orthopaedics Trauma surgery

Article was published inPerspectives in Surgery

2015 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Breast cancer at the 1st Surgical Department, University Hospital Olomouc − assessing the number and age of patients and benefit of breast screening

- Intramural haematoma of the oesophagus – a case report and literature review

- Swimming pool suction injury: etiology, profylaxis and management

- Phyllodes breast tumors

- Strategies of treatment of chest wall tumors and our experience

- The benefit of PET/CT in the diagnosis and treatment of esophageal cancer

- Perspectives in Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Phyllodes breast tumors

- Strategies of treatment of chest wall tumors and our experience

- Intramural haematoma of the oesophagus – a case report and literature review

- Swimming pool suction injury: etiology, profylaxis and management

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career