-

Medical journals

- Career

Pancreatic leakage and acute postoperative pancreatitis after proximal pancreatoduodenectomy

Authors: J. Rudis; M. Ryska

Authors‘ workplace: Surgery department of the 2. Faculty of medicine, Charles University and Central military hospital in Prague head of department: prof. MUDr. M. Ryska, CSc.

Published in: Rozhl. Chir., 2014, roč. 93, č. 7, s. 380-385.

Category: Original articles

Overview

Introduction:

Acute postoperative pancreatitis (APP) after proximal pancreatoduodenectomy (PDE) is a major and serious complication. The purpose of the the study is early diagnosis of APP, differentiation from pancreatic stump leak and possibilities of surgical treatment.Material and methods:

Of all patients who underwent PDE for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head complicated by type C pancreatic leak, who died during primary hospitalization, we used autopsy findings to find patients with histologically confirmed APP. We compared this group to patients with only a pancreatic leak and patients with an uncomplicated clinical course. We retrospectively evaluated the postoperative clinical course, and radiological and laboratory data of all patients. These parameters were statistically compared between the individual groups using Fisher LSD test. We considered p = 0.05 to be statistically significant. Data were analysed using software STATISTICA 10.0 (StatSoft CR s.r.o.).Results:

One hundred sixty patients underwent PDE for ductal adenocarcinoma at our institution between 2007−2011 and were retrospectivaly reviewed. APP with postoperative type C pancreatic leak was observed in 4 (2.5%) patients; none of these patients survived. We found significantly higher levels of serum pancreatic amylase (AMS) on the 1. postoperative day in 3 of these patients compared to the other groups. Significantly increasing levels of CRP during the the first 5 postoperative days were observed in 75% of these patients. Retrospectively analysed contrast CT scans up to the 5th POD did not show APP. Only 1 patient had findings of APP type E according to Balthazar on CT scan performed on the 9th POD.Conclusion:

The most significant factor in early diagnosis of APP after PDE is an abrupt change in clinical status. We also observed significantly higher levels of serum concentrations of CRP and AMS. Based on our findings, CT scan is not beneficial in the early diagnosis of APP. In cases of early diagnosed APP after PDE, the question of performing a completion pancreatectomy and its timing remains.Key words:

Pancreatic leakage − acute postoperative pancreatitis – proximal pancreatoduodenectomy − drainage − total pancreatectomy.INTRODUCTION

Acute postoperative pancreatitis (APP) is a less frequent but very serious surgical complication with often fatal results. It is most often seen following surgery on the pancreas itself, but in rare cases has also been described after surgical procedures on organs very distant from the pancreas.

The incidence of APP following proximal pancreatoduodenectomy (PDE) ranges from 1.9–50% [1,2,3]. Contrary to acute pancreatitis with a 5–15% mortality, the mortality of APP is described as almost 80% [3].

The aim of our work was to evaluate the possibilities of early diagnosis of APP as well as solely a type C pancreatic leak during PJA dehiscence in patients after PDE for carcinoma of the pancreatic head and consider subsequent therapeutic procedures.

Material and methods

Patients with ductal carcinoma of the pancreatic head T1–3, N1, M0 underwent PDE according to Traverso [4] with end to side PJA, HJA and DJA to the first jejunal loop. Some of the patients received Octreotide (by Novartis) according to Büchler as hormonal prevention of postoperative pancreatitis [5]. Postoperatively on the 1., 3., and 5. POD, as part of standard monitoring, we analyzed the levels of pancreatic amylase in the serum and in the drain secretion along with the volume over 24 hours. At these times we also analyzed the levels of inflammatory markers (leukocytes, CRP) in the patients’ serum. Pancreatic leak was classified as type A-C according to Bassi [6]. Ultrasound examination was not standardly performed after PDE.

In patients with type C leak and alteration of inflammatory response, an abdominal CT with contrast was performed and revision surgery was indicated. In patients with findings of APP causing PJA dehiscence, as well as in patients with findings of only dehiscence, a PJA disconnection was performed with closure of the jejunal stump and introduction of peripancreatic drainage.

We retrospectively evaluated the possibility of differentiating acute postoperative pancreatitis from simple PJA leak based on contrast CT examination, levels of pancreatic amylase and inflammatory markers in the serum in the patients that died as well as those who survived the complication. We also analyzed drain secretions.

Based on the autopsy findings, we divided the patients into two groups: the first with APP and pancreatic leak, and the second with only pancreatic leak. Both of these groups were compared to the group of patients with an uncomplicated postoperative course.

Statistical analysis

We used repeated measures analysis of variance to compare the individual studied parameters in the postoperative course. Post-hoc comparison was performed using Fisher LSD test. The main indicators and their interaction over a period of time were studied in each group of patients. The level of statistical significance was set to p = 0,05. All analyses were performed in the program STATISTICA 10.0 (StatSoft CR s.r.o.).

Results

Between the years 2007–2011, 160 patients with histologically confirmed ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head underwent PDE at the Surgery department of the 2. Faculty of medicine, Charles University and Central military hospital in Prague. Type C pancreatic leak was observed in 14 (8.75%) patients. Of these patients, 7 (50%) died in direct association with this complication, which is 4.36% of the total number of operated patients. In all patients the macroscopic findings during surgical revision were indicative of acute postoperative pancreatitis with development of pancreatic fistula. Autopsy, however, revealed findings of acute postoperative pancreatitis in only 4 cases (57%) (Tab. 1).

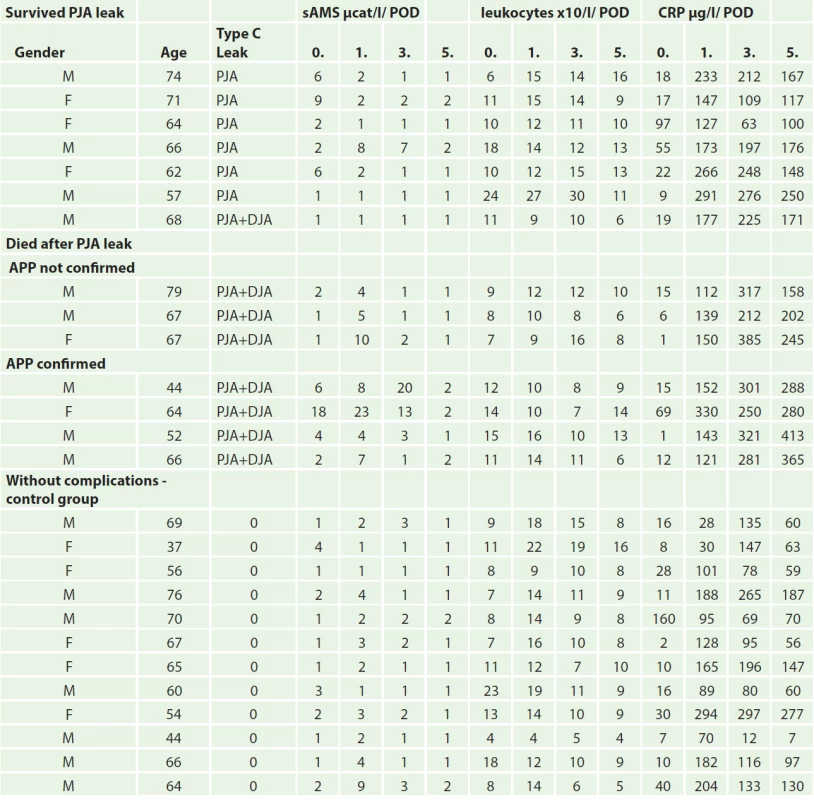

1. Classification of patients after duodenopancreatectomy and their postoperative laboratory parameters.

Note: PJA – pancreatojejunoanastomosis, DJA − duodenojejunoanastomosis CRP values on the 0. POD were similarly increased in all groups, on the 1. POD further increase was also similar in all groups. Differences were observed on the 3. and 5. POD, where a statistically significant increase was seen in the APP group, while a decrease was observed in the other groups on the 5. POD (Tab. 1, Graph 1).

Graph 1: Evaluation of CRP levels for each group of patients

A significant difference in serum amylase levels was observed during post-hoc analysis between the group with APP and group of uncomplicated patients compared to the group of patients with type C pancreatic leak (p = 0,016) on the 0., 1., and 3. POD. On the 5. POD, the concentration of serum amylase decreased in all groups and the results were not statistically significant (Graph 2).

Graph 2: Evaluation of sAMS levels for each group of patients

No significant differences in leukocyte levels were observed between the patient groups (Graph 3).

Graph 3: Evaluation of leukocyte levels for each group of patients

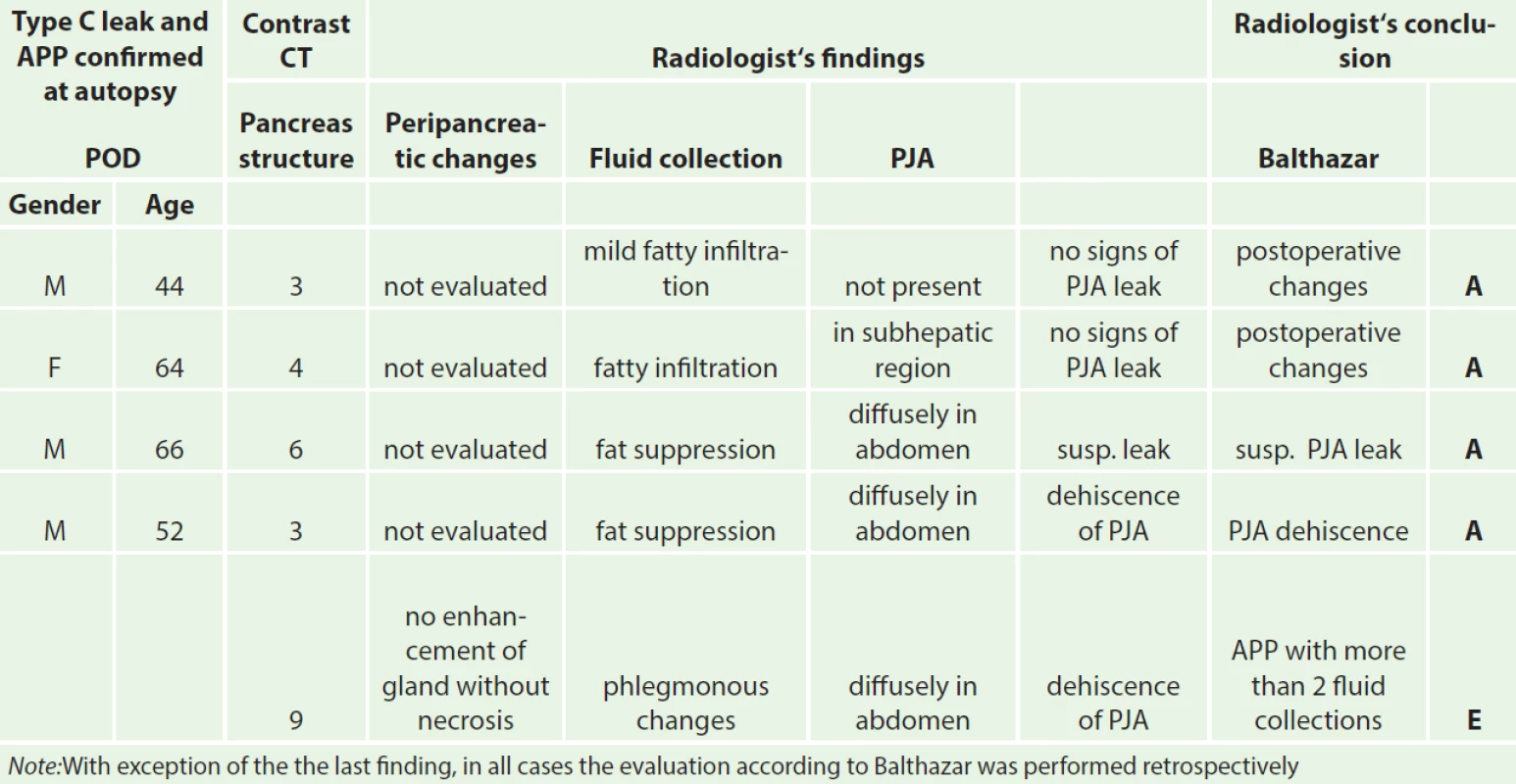

CT examination prior to revision surgery in all 14 cases described postoperative changes, various fluid collections and even leaks. Clear signs of changes in the structure of the pancreas according to Balthazar as seen in APP were not described in any of the patients up to the 5. POD (Tab. 2).

2. Evaluation of CT findings according to Balthazar classification in patients after PDE with type C leak and APP

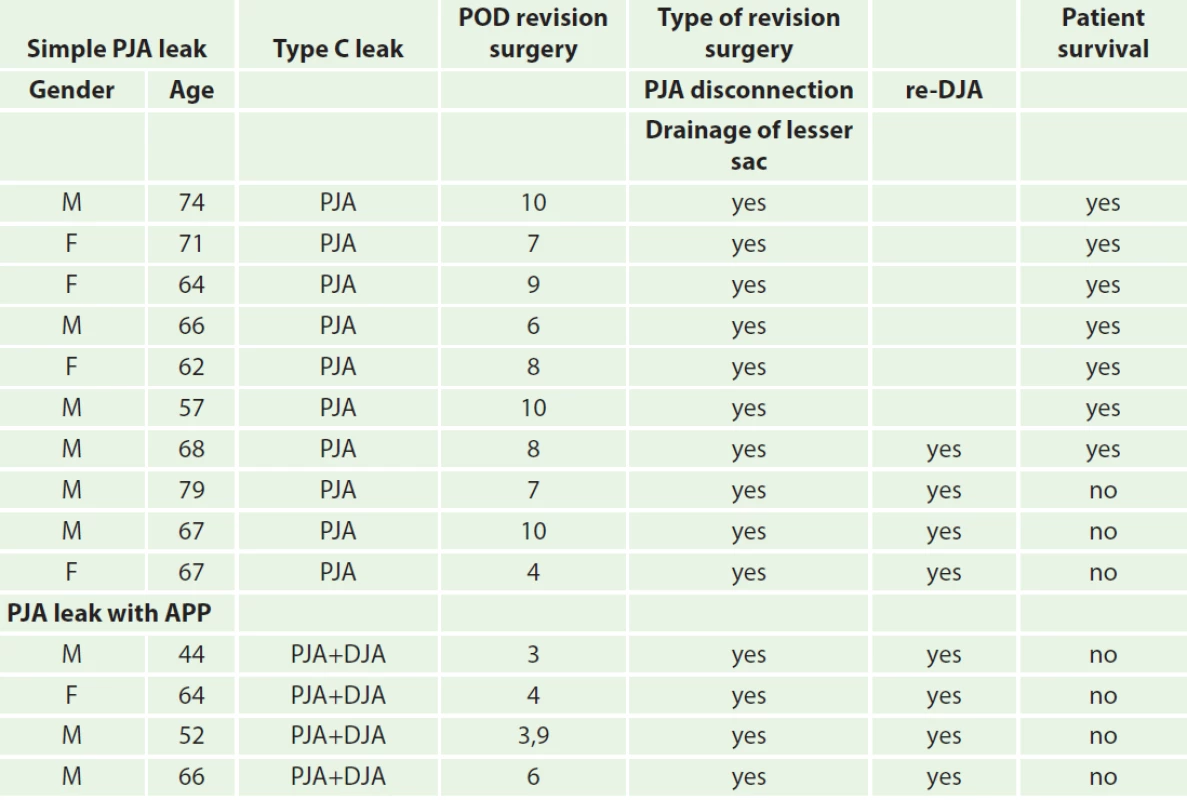

We retrospectively discovered that in all 4 patients in which APP was determined at autopsy, a PJA disconnection and peripancreatic drainage was performed during revision surgery. Thus the surgical procedure did not differ from surgical treatment of a simple type C pancreatic leak (Tab. 3)

3. Final patient classification based on the postoperative complication and type of reoperation

Note: PJA – pancreatojejunoanastomosis; re-DJA – disconnection of the original duodenojejunoanastomosis and construction of a new one Discussion

The most serious complication after proximal pancreatoduodenectomy is a type C pancreatic leak, either as a consequence of APP, or independently from APP (Tab. 3). Differentiating between these two types of complications is often very difficult, if not impossible. To date, there are no definite guidelines on how to proceed in such situations [7].

APP is clinically defined as abdominal pain which develops during the postoperative course with a concurrent two - to three-fold increase in the levels of specific pancreatic enzymes in the blood. Evaluation may however be complicated by the development of benign postoperative hyperamylasemia and the subjective perception of postoperative pain [8,9].

A non-standard postoperative course accompanied by pain, distension of the abdominal muscles, prolonged paralytic ileus and cloudy, often brownish, discharge from the drains may signify developing APP [10].

The development and rate of progression of APP in the early postoperative course are very difficult to evaluate. Clinical symptoms may be hidden, especially if the patient remains under analgosedation, or even on artificial lung ventilation, after a long operation with greater blood loss.

The first warning sign of the development of APP may be progressive circulatory instability, especially in patients with replenished blood supply [10]. Nonetheless a similar condition may also be caused by other postoperative complications. In a study by Wilson et al. [11] which clinically evaluated the postoperative course APP was only diagnosed at autopsy in 10 of 11 cases. Therefore we did not evaluate clinical symptoms in our study.

Operative findings on revision also do not always correlate with the results of laboratory and imaging examinations. In our set of patients who died in direct association with a serious postoperative pancreatic leak from the PJA, APP occurred in 4 out of 7 cases (57%) based on autopsy histological findings. All of these patients were suspected of having APP based on macroscopic findings during revision surgery.

Pancreatic leak from PJA and peripancreatic abscess may be clinical signs of APP. They may however also develop due to technical error during sewing of the anastomosis, where edge necrosis may occur in an otherwise undisturbed glandular parenchyma. During surgical revision in a postoperatively changed terrain, pathological changes in the remaining pancreas and its surroundings are often difficult to evaluate due to signs of superficial tissue digestion and the presence of necrosis, which develop due to digestion by activated pancreatic juice. Postoperative changes in cases of simple pancreatic leak may easily be misinterpreted for signs of APP and vice-versa.

A possible leak in preoperative diagnosis may be histological examination. This examination however is often only an approximation and is not always available.

In 1957 P. Milleret [12] assessed the benefit of preoperative biopsy for a surgeon as being not very informative and dangerous, therefore unjustified. In the same year however, Mallet-Guy [13] pronounced this procedure to be beneficial and safe. Currently, pancreatic biopsy is considered a safe procedure, yet there is no clear view as to its indication [14].

Regarding laboratory analysis, in addition to values of amylase, lipase and trypsin levels, Büchler also favors analysis of CRP and calcium levels [15]. In recent years, diagnosis of APP has most often been reliant on CRP level along with the result of spiral contrast CT examination, where necrotic changes in the parenchyma are evaluated according to the Balthazar classification [16]. In accordance with current literary findings, CRP levels best reflect the development and course of the disease. In contrast, CT examination performed prior to surgical revision has not shown to be beneficial in terms of evaluating changes in the pancreatic gland. Prior CT examinations did not describe structural changes in the pancreas in any of the four cases of autopsy-confirmed APP, not even on retrospective evaluation.

The development of acute postoperative pancreatitis in combination with findings of type C pancreatic leak almost always leads to death of the patient. PJA disconnection and drainage procedures during surgical revision after DPE in cases of acute postoperative pancreatitis are usually insufficient and do not lead to a better prognosis. Early diagnosis of APP based on clinical and laboratory results is very difficult from standard currently performed examinations, as is the evaluation of preoperative findings during reoperation, especially after a longer interval from the primary operation.

An appropriate, although risky, solution during early revision with suspicion of APP is a completion pancreatectomy with splenectomy. However, after late revisions in an operating field devastated by pancreatitis, the mortality of patients after completion pancreatectomy nears 100%, according to most authors. Therefore it is desirable to proceed with the completion pancreatectomy soon after the primary procedure.

Contrarily, performing a completion pancreatectomy in a patient with a simple type C leak may be an unwarranted procedure, unjustifiably risky with subsequent significant worsening of quality of life. Early diagnosis of APP may therefore be a key moment in the treatment of type C postoperative leak in patients after PDE.

A basic aim of our study was to confirm or rule out a diagnosis of APP in the interval from the primary surgical procedure to the surgical revision, with respect to our standard type of surgical procedure (disconnection and closure of the jejunal stump and peripancreatic drainage). Our retrospective evaluation showed that we were mistaken in almost half of the patients. Subsequent decision to perform a disconnection of the pancreatojejunoanastomosis with drainage of the resected area with planned pancreatic fistula did not reflect the current view on treatment of this complication. This error, in both diagnosis and type of surgical revision, has also been presented by other authors, who came to very similar conclusions based on retrospective analyses [17,18]. Completion pancreatectomy can be of significant benefit when performed as soon as possible after diagnosis of potentially fatal APP [19]. The longer the interval between primary operation and surgical revision, the lower the chance of performing completion pancreatectomy without endangering the life of the patient. Due to the gradual postoperative development of inflammatory peripancreatic infiltrate, the procedure becomes intolerable for the patient. In any case, the decision to perform completion pancreatectomy is very difficult for the surgeon.

If we retrospectively evaluate our patient group and our reaction to the obtained values - markers - of APP, it is necessary to state that we rather underestimated the increasing values and were of the opinion that the values reflect developing pancreatic leak and that we have time and will observe the patient. We evidently missed the opportunity to perform early surgical revision and remove the remaining pancreas.

Another discovery was the evaluation of the postoperative finding on the remaining pancreas. We attributed superficial necroses to developing APP; autopsy findings, however, did not confirm APP. Evidently these were superficial changes caused by digestion of pancreatic tissue by activated pancreatic juice from PJA dehiscence. In accordance with other authors, we do not consider peroperative biopsy to be of value. The surgeon’s experience determines not only whether APP will be diagnosed early enough and will be differentiated from simple pancreatic leak, but also whether a completion pancreatectomy will be performed in indicated cases.

CONCLUSION

The most serious complication after proximal pancreatoduodenectomy is a type C pancreatic leak, either as a consequence of APP, or independently from APP. Differentiating between these two types of complications is often very difficult, if not impossible. The results of our retrospective study confirmed the following:

- an abrupt increase in values of serum amylase and CRP from the 1st to 5th postoperative day is indicative of the development of acute postoperative pancreatitis following proximal pancreatoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma,

- CT examination may not be beneficial in diagnosing this complication,

- when life-threatening acute postoperative pancreatitis is diagnosed, a completion pancreatectomy is recommended. The decision depends on the surgeon’s experience,

- in some patients, acute postoperative pancreatitis may not be confirmed on biopsy or autopsy; changes on the remaining pancreas may only be superficial, caused by digestion of activated pancreatic juice leaking from dehiscence of the pancreatojejunoanastomosis.

MUDr. Jan Rudiš

Chirurgická klinika 2. LF UK a ÚVN, Praha

U vojenské nemocnice 1200

160 00 Praha 6

e-mail: jan.rudis@uvn.cz

Sources

1. Krieger AG, Kubishkin VA, Karmazanovskiy GG, Svitina KA,Kochatkov AV, et al. The postoperative pancreatitis after the pancreatic surgery. Khirurgiia (Mosk) 2012;4 : 14−19.

2. Kothaj P. Chirurgická liečba rakoviny pankreasu. Banská Bystrica 1996;96.

3. Ryska M. Akutní pooperační pankreatitida – mýtus nebo realita? HPB 2000;8 : 6−9.

4. Traverso LW, Longmire WJ. Preservation of the pylorus in pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1978;146 : 959−962.

5. Z´gragen K, Uhl W, Buchler MW. Acute postoperative pancreatitis kniha. In: Pancreas, Heidelberg 1998 : 283−290.

6. Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138 : 8−13.

7. Dellaportas D, Tympa A, Nastos C, Psychogiou V, Karakatsanis A, et al. An ongoing disput in management of severe pancreatic fistula: Pancreatosplenectomy or not? World J Gastrointest Surg 2010;2 : 381−384.

8. Z´ green K, Aronsky D, Maurer CA, et al. Acute postoperative pankreatitis after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Results of prospective Swiss Assotiation of laparoscopic et thoracoscopic surgery study. Arch Surg 1997;132 : 1026−1030.

9. Niederle B a kol. Chirurgie žlučových cest. Praha, Avicenum 1977.

10. Büchler MW, Friess H, Klempa I, et al. Role of octreotide in the prevention of postoperative complications following pancreatic resection. Am J Surg 1992;163 : 125−130.

11. Wilson C, Imrie CW. Deaths from acute pancreatitis: Why do we miss the diagnosis so frequently? Int J Pancreatol 1988;3 : 273−282.

12. Milleret P. Histoire d´une biopsie pancréatique. Lyon chir 1957;53 : 107−109.

13. Mallet-Guy P. Alleged hazards of pancreatic biopsy. Lyon Chir 1957;53 : 126−7.

14. de Castro SM, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Incidence and management of pancreatic lakage after pancreatoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 2005;92 : 1117−1123.

15. Büchler MW, Gloor B, Muller CHA, Friess H, Seiler CHA, et al. Acute necrotising pancreatitis: Treatement strategy according to the status of infection. Ann of Surg 2000;232 : 619−626.

16. Balthazar EJ. CT diagnosis and staging of acute pancreatitis. Radiol Clin North Am 1989;27 : 19−37.

17. Cullen JJ, Sarr MG, Ilstrup DM. Pancreatic anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, significance, and management. Am J Surg 1994;168 : 295−298.

18. Haddad LB, Scatton O, Randon B, Andraus W, Massault PP, et al. Pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: the conservative treatement of choice. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11 : 203−209.

19. Farley DR, Schwall G, Trede M. Completion pancreatectomy for surgical complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 1996;3 : 176−179.

Labels

Surgery Orthopaedics Trauma surgery

Article was published inPerspectives in Surgery

2014 Issue 7-

All articles in this issue

- Interdisciplinary European guidelines on metabolic and bariatric surgery

- Risks and complications of urological surgical procedures in elderly patients

- Staged management of open tibial fractures with soft tissue defect

- Sarcoma of the chest wall after radiotherapy for breast carcinoma – a case report

- Treatment strategy for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms

- Pancreatic leakage and acute postoperative pancreatitis after proximal pancreatoduodenectomy

- Perspectives in Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Treatment strategy for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms

- Sarcoma of the chest wall after radiotherapy for breast carcinoma – a case report

- Risks and complications of urological surgical procedures in elderly patients

- Pancreatic leakage and acute postoperative pancreatitis after proximal pancreatoduodenectomy

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career