-

Medical journals

- Career

The relationship between psychological safety and burnout among nurses

Authors: J. Vévoda 1; Š. Vévodová 1; M. Nakládalová 2; B. Grygová 1; H. Kisvetrová 3; E. Grochowska Niedworok 4; J. Chrastina 5; D. Svobodová 6; P. Przecsková 7; L. Merz 1

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Palacký University Olomouc, Czech Republic head of department Mgr. Šárka Vévodová, Ph. D. 1; Department of Occupational Medicine, University Hospital Olomouc and Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Czech Republic head of department doc. MUDr. Marie Nakládalová, Ph. D. 2; Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Palacký University Olomouc, Czech Republic head of department Mgr. Zdena Mikšová, Ph. D. 3; Department of Dietetic, University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland. 4; The Institute of Special Education Studies, Faculty of Education, Palacký University Olomouc Czech Republic head of institute doc. PhDr. Eva Souralová, Ph. D. 5; General University Hospital in Prague, Czech Republic head of hospital Mgr. Dana Jurásková, Ph. D., MBA 6; University Hospital in Ostrava, Czech Republic head of hospital doc. MUDr. David Feltl, Ph. D., MBA 7

Published in: Pracov. Lék., 68, 2016, No. 1-2, s. 40-46.

Category: Original Papers

Overview

Objective:

Every day, health workers are endangered by both physical and psychological injuries. While physical safety at work is well controlled and ensured by employers, much less attention is paid to psychological safety. The main objective of the study was to determine the level of psychological safety at work in general nurses and its relationship to burnout syndrome.Material and Methods:

In late 2014 and early 2015, a quantitative questionnaire survey was conducted on a sample of 275 general nurses working in four hospitals in the Czech Republic. Data were collected using a questionnaire battery consisting of the standardized Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and a scale to measure psychological safety. A part of current research was also the lingvistic validation of the scale to measure psychological safety in the Czech language.Results:

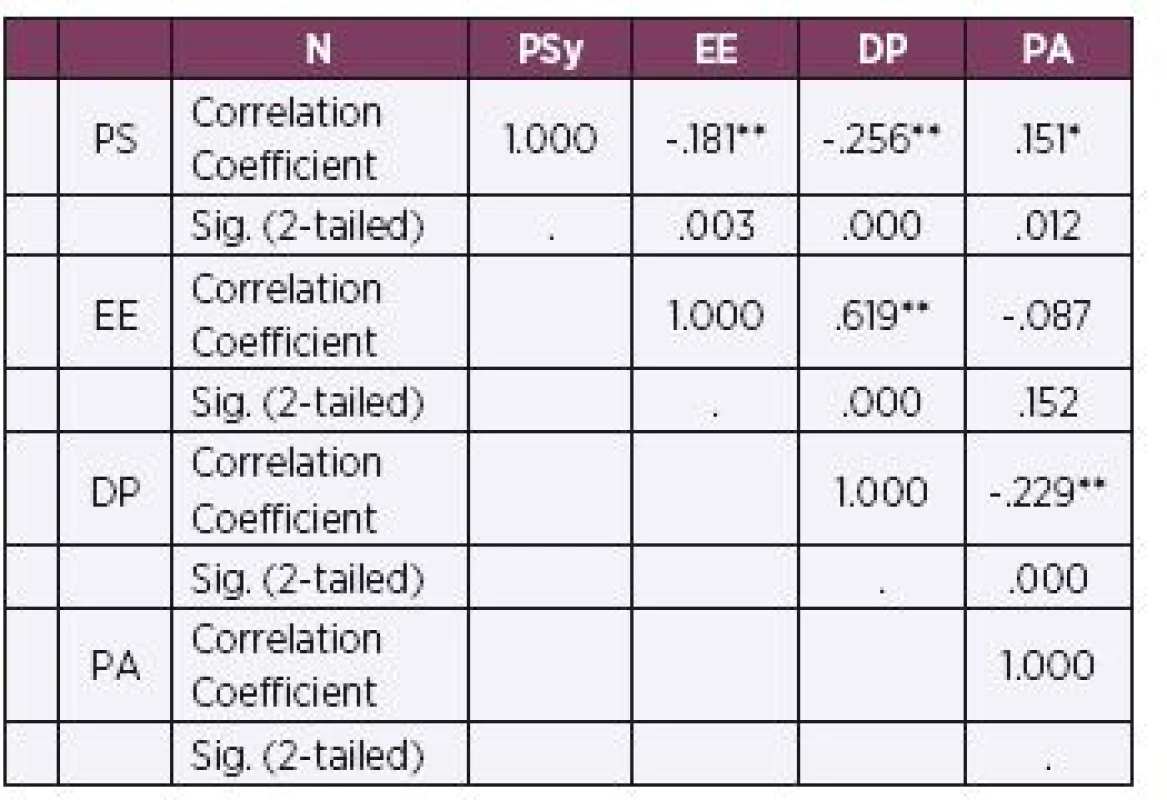

The survey results showed significantly negative relationships between emotional exhaustion and psychological safety at work (r = -0.181**, see Table 2) and between depersonalization and psychological safety (r = -0.256**, see Table 2), and a weak positive relationship between personal accomplishment and psychological safety (r = 0.078*, see Table 2). Statistical analyses also showed that respondents with confirmed burnout in emotional exhaustion (p < 0.001) and depersonalization (p < 0.001) dimensions had significantly lower levels of psychological safety. Significantly higher level of psychological safety had non-burned out respondents in personal accomplishment (p = 0.001).Conclusions:

A safe working environment is one of the key prerequisites for the well-being of health workers and one of the necessary preconditions for providing high-quality health care. Health service managers should aim not only at maintaining physical safety at work but also at ensuring an optimum level of psychological safety.Keywords:

general nurse – hospital – MBI – psychological safety – burnoutINTRODUCTION

Work is to develop one’s personality, motivate them and, as a consequence, improve their health. If, however, inadequate working conditions affect employees for a longer time, psychosomatic disorders such as headaches or gastric neurosis may develop, as well as depression, burnout and drug or alcohol abuse [15, 24].

Workplace should provide physical as well as psychological safety. The roots of psychological safety can be traced back to the 1970s. Schein and Bennis suppose that psychological safety is necessary for an individual’s sense of security and for their ability to deal with organization challenges. Basically, it means the reduction of interpersonal risk accompanying insecurity related to a change [28]. Psychological safety helps people to overcome learning anxiety when facing the facts which are contrary to their expectations. Individuals with the sense of psychological safety focus on common objectives instead of self-defence [27]. At the turn of the century psychological safety underwent a renaissance. The concept is important in order to understand how people cooperate to achieve common objectives [6].

Edmonson describes psychological safety as an individual’s belief that if they make a mistake at work neither they will be inadequately punished for it nor their interpersonal relations will change [7]. Kebza and Šolcová add that one may feel confident to ask their colleagues for advice, help or feedback without fearing to be viewed as incompetent [14]. Edmondson states that it is also an employee’s conviction that if the propose a change or another novel idea, or report a mistake, such behavior will not have a negative impact on interpersonal relations [6]. The level of psychological safety shows how individuals perceive interpersonal risks and their consequences in their working environment [6]. Individuals experience psychological safety when they may deal with their colleagues without a fear that this will lead to psychological harm. These may be either personal or work-related conversations, for example those concerning shortcomings in the working environment [29]. If employees feel psychologically safe in the environment, they are better at identifying risks, more engaged and taking more responsibility for their results, they are more creative and their subjective vitality experience increases, which leads to positive changes in the workplace [7]. Thus, where psychological safety is present, a creative approach to work and an increase in the employees’ subjective experience of vitality may be expected [13]. However, psychological safety does not mean a cozy and comfortable environment and having friends around; it does not even tell about the absence of a burden or problems. The term refers to a climate in which team members are free to discuss, thus allowing early prevention of problems and fulfillment of common goals [6].

It has been shown that there is a relationship between psychological safety at work and burnout syndrome [14]. Burnout syndrome is particularly common in occupations where the main work components are contacts with others and dependency on their evaluation [22]. Health care is an area with a high prevalence of burnout syndrome. Burnout is associated with numerous negative consequences for not only health professionals but also employers or patients/clients themselves. The consequences include decreased quality of care [23], negative changes in job satisfaction [12] and a high turnover of general nurses, a serious problem in health care [21], psychological safety [20]. Therefore, prevention of burnout syndrome is of paramount importance. An important component of such prevention is ensuring psychological safety.

The questionnaire survey aimed at determining the level of burnout syndrome in general nurses and its relationship to psychological work safety as a protective factor. We assumed the existence of a significant relationship between the level of burnout in general nurses and the level of psychological safety at work. The research may initiate further steps to improving situation in this area.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Palacký University Olomouc.

The survey was carried out using the quantitative method with the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [26] and a scale to measure psychological safety published by Edmondson [5]. The survey was a part of pre-testing of the scale to measure psychological safety adapted into the Czech language using guidelines by Beaton et al. [2, 3] and Guillemin et al.[8].

Edmonson [5] scale to measure psychological safety comprises six Likert scale items, represented by Likert scales from 1-strongly disagree to 7-strongly agree, such as If you make a mistake on this team, it is often held against you. [Pokud se v pracovním kolektivu dopustíte nějaké chyby, je vám to často vyčítáno]. Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues. [Členové pracovního kolektivu jsou schopni poukazovat na problémy a nepříjemné záležitosti]. People on this team sometimes reject others for being different. [Lidé v kolektivu někdy nepřijmou druhé kvůli jejich odlišnosti].

Within the Scale pretest the internal consistency of individual statements was determined, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.829.

Translation procedure

Prior to the research itself it was necessary to translate scale to measure psychological safety into Czech and adapt it to the Czech sociocultural environment. We had to gain the approval of the scale to measure psychological safety author, Prof. Amy C. Edmondson from Harvard University.

The Scale of psychological safety was translated from English to Czech and back from Czech to English. The methodology based on the needs of medical, sociological and psychological research includes five steps [2, 3, 8]:

I. The scale to measure psychological safety was translated from English to Czech by two independent translators.

II. Translations synthesis was carried out by a proofreader solving discrepancies.

III. Back-translation to English was carried out by two native speakers whose second language is Czech.

IV. Methodology workshop evaluated sociocultural and linguistic quality of the translations, content validity and appropriateness of the methodology used. The expert team included a methodologist, a psychologist and two translators. To clarify the terms and expressions, we communicated directly with prof. Edmondson. The workshop resulted in the final version of the scale to measure psychological safety suitable for pre-testing.

V. The scale to measure psychological safety pre-tests.

The scale to measure psychological safety translations from English and their syntheses as well as the back-translation into English were done by Skřivánek Language School.

The presented research is a part of the pre-test of linguistic validation of the scale to measure psychological safety.

To determine the level of burnout, a Czech version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory – General Survey (MBI-GS) [10] was used; the questionnaire by C. Maslach addresses three main factors of burnout: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP) and personal accomplishment (PA) [26]. The instrument comprises 16 items to be answered on Likert scales from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). For the assessment, all scores for the individual scales are added up. For the MBI-GS, Cronbach’s alphas are α = 0.86 for EE, α = 0.70 for DP and α = 0.82 for PA

The criterion for including participants in the survey was working as a general nurse for at least one year. The survey was carried out in four hospitals between October 2014 and February 2015. A total of 275 responders were approached. Participation in the survey was voluntary, with all respondents being informed about its nature. The questionnaires were distributed among selected nurses by one of the researchers. The forms were filled in anonymously, placed in sealed envelopes and deposited in a special box.

The obtained data were statistically analyzed with the IBM SPSS Statistics Base 19 software. Normality of the distribution of results was estimated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The significance of differences between burned-out and non-burned out participants in the area of psychological safety was determined with the Mann-Whitney U test. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. The relationships between individual components of burnout and psychological safety were assessed with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient at levels of significance of p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.05. The data on psychological safety levels in the groups of burned-out and non-burned out participants are presented as the mean, standard deviation, mode, median, minimum and maximum values.

RESULTS

The respondents’ mean age at the time of survey was 39.4 years (SD = 9.58; range, 23–62 years). The mean length of service was 17 years (SD = 10.75; range, 1–42 years). The sample comprised 2 males and 273 females.

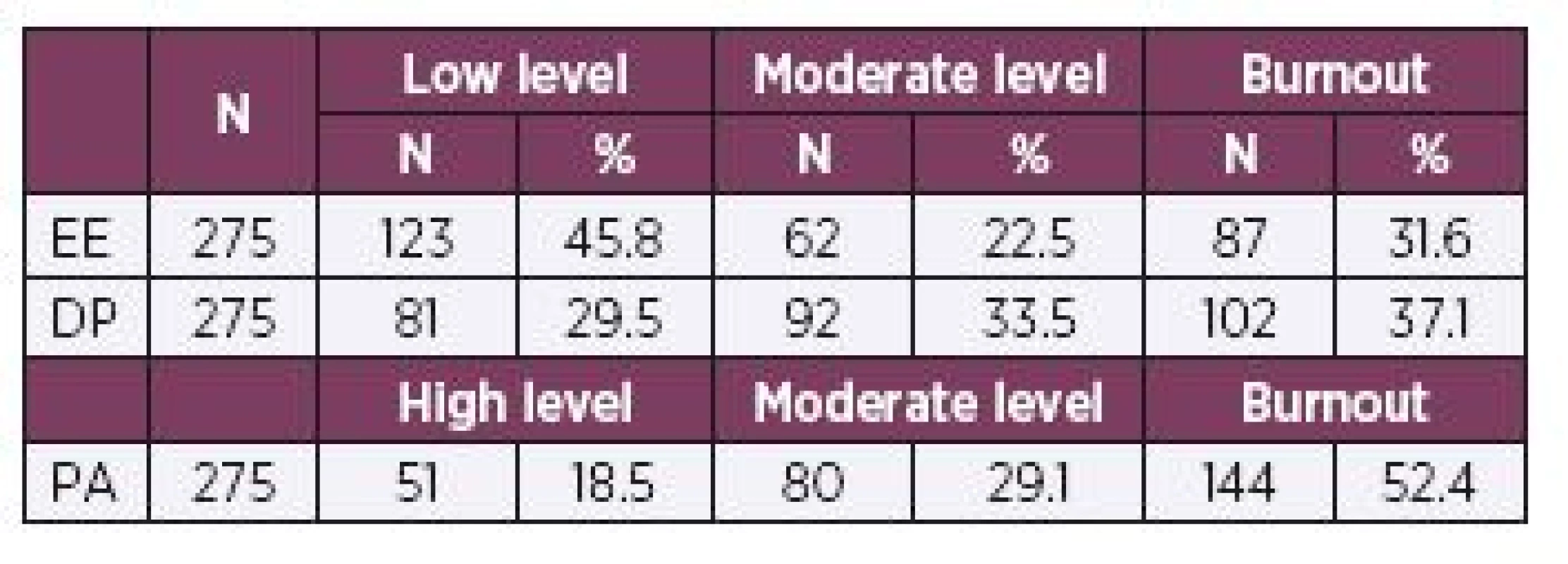

From a total of 275 participants, high levels of burnout were observed in 87 (31.6%) nurses in the EE subscale, 102 (37.1%) nurses in the DP subscale and 144 (52.4%) in the PA subscale (see Table 1)

1. Burnout level (EE, DP a PA)

2. Correlation coefficients for psychological safety and the burnout components

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). EE = emotional exhaustion DP = depersonalization PA = personal accomplishment Psy = psychological safety All three components of the burnout syndrome, that is, EE D(275) = 0.125, p < 0.001, DP D(275) = 0.117, p < 0.001 and PA D(275) = 0.053, p = 0.005, showed significant deviations from the normal distribution. Similarly, data on psychological safety, D(275) = 0.890, p < 0.001, showed a significant deviation from the normal distribution. Given the character of data, nonparametric tests were used for their assessment.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient showed a statistically significant negative relationship between the levels of psychological safety at work and emotional exhaustion (rs = -0.181; p < 0.01), suggesting that increasing levels of psychological safety at work are associated with a lower risk for emotional exhaustion.

Analysis of the second component of burnout, depersonalization, also found a statistically significant negative relationship with the level of psychological safety at work (rs = -0.256; p < 0.01). It means that an increase in psychological safety at work is associated with decreasing levels of depersonalization.

There was only a very weak positive correlation between psychological safety and personal accomplishment (rs = 0.078; p < 0.05).

The Mann-Whitney U test indicates statistically significant differences in psychological safety levels in the EE dimension between burned out and non-burned out respondents, U = 5,997; p < 0.001).

The same test also revealed a statistically significant difference in the level of psychological safety at work between burned out and non-burned out participants in the DP dimension, U = 6,726; p < 0.001).

The level of psychological safety was significantly lower in burned out than in non-burned out participants in the EE and DP dimensions.

The Mann-Whitney U test proved statistically significant difference in the level of psychological safety between respondents burnt out in the PA area and respondents non-burnt out in the PA area, U = 11.689, p = 0.001).

It means, non burnout respondents in the PA had higher level of psychological safety than burnout respondents.

DISCUSSION

The survey aimed determine the level of burnout syndrome in general nurses and its relationship to psychological work safety as a protective factor. The burnout is long-term problem in nursing. The present research revealed a high level of the burnout among nurses: 31,6%, DP – 37,1%, PA 52,7%. These values were compared with similar Iranian research which showed that 34.6, 28.8, and 95.7% of the nurses had both high EE and DP and high reduced PA [18]. Moustaka et al. found that 45.3% of the sample experienced a high level of EE, 40.6% high level of DP. A high PA is present in 34.3% of the sample [19]. High burnout level among nurses was significantly associated with nurses’ appraisals of quality of care [23]. Poghosyan L Psychological safety at work should be a common feature, particularly in health care, according to Schaefer, Helmreich and Scheideggar, because 70% to 80% of health care mistakes are related to interactions within teams [25]. A Malaysian longitudinal study showed an association between psychosocial safety climate and emotional exhaustion [11]. As we assumed, our study revealed a negative relationship between psychological safety in both EE and DP. A weak positive association was found in PA. The present survey conforms to the results of a meta-analysis carried out by Nahrgang, Morgenson and Hofmann [20]. They confirmed a statistically significant relationship between the levels of psychological safety at work and the burnout syndrome.

Our study showed that the levels of psychological safety were statistically significantly lower in the burned out respondents than in the non-burned out ones.

Leiter and Laschinger reported a significant relationship between psychological safety and engagement. [16]. They studied determinants of psychological safety with a respect to organizational culture and climate and constructed a model where the perception of psychological safety was predicted by civility and agreement between personal and organizational values in the workplace [16].

The existence of a significant negative relationship between the burnout levels and workplace civility was also confirmed by Havrdová and Šolcová [9].

Awareness of the factors that influence the psychological safety of health professionals is necessary to provide them with essential care and support. This, in turn, promotes psychological safety of patients, improving quality of health care [1]. Psychological safety at work will play an increasing role in managing changes in society and the nature of work [4].

The present study has highlighted the importance of psychological safety at work in the Czech Republic. A limitation is the cross-sectional design of the study, which cannot be generalized to the entire population of nurses. A longitudinal study would be more appropriate for determining the relationships between the variables.

CONCLUSION

The survey deals with psychological safety at work as a protective factor regarding burnout syndrome. This factor is very closely related to the quality of nursing care and, as a result, with patient satisfaction. The survey aimed at determining the effect of psychological safety at work on burnout syndrome in general nurses. In both emotional exhaustion and depersonalization dimensions, the levels of psychological safety were statistically significantly lower in burned out than in non-burned out responders.

The risk factors for burnout, such as personal characteristics, stress-coping strategies and social support, are beyond the employers infuence; however, psychological safety at work is a factor that may be modified by employers. By introducing preventive measures related to the psychosocial environment, employers may also indirectly influence the health status of their employees [17].

A safe working environment is an essential prerequisite for the general well-being of health workers, allowing the accomplishment of the main mission of health care providers, that is, prevention, treatment and patients return to everyday life.

Acknowledgements

Student Grant Competition Palacky University in Olomouc: Psychological work safety in non-medical healthcare professions (FZV_2015_007)

Do redakce došlo 31. 3. 2016.

Do tisku přijato dne 8. 4. 2016.

Adresa pro korespondenci:

Mgr. Jiří Vévoda, Ph.D.

Ústav společenských a humanitních věd FZV, UP

Hněvotínská 3

775 15 Olomouc

e-mail: jiri.vevoda@upol.cz

Sources

1. Aranzamendez, G., James, D., Toms, R. Finding Antecedents of Psychological Safety: A Step Toward Quality Improvement. Nursing forum, 2014. doi:10.1111/nuf.12084.

2. Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., Ferraz, M. B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 2000, 25, 24, s. 3186–3191.

3. Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., Ferraz, M. B. Recommendations for the Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the DASH & Quick DASH Outcome Measures [on line]. Institute for Work & Health, 2007 [cit. 2013-12-06]. Dostupné na www: http://dash.iwh.on.ca/system/files/X-CulturalAdaptation-2007.pdf.

4. Beck, U. Riziková společnost. Na cestě k jiné moderně. Praha: Sociologické nakladatelství, 2004, 431 s.

5. Edmondson, A. C. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Admin Sci Quart, 1999, 44, 2, s. 350–383. doi:10.2307/2666999.

6. Edmondson, A. C. Psychological safety, Trust and Learning in Organizations: A Group-Level Lens. In: Kramer, M., Cook, K. S. (eds.). Trust and distrust in organizations: dilemmas and approaches. New York, 2004, s. 239–272.

7. Eggers, J. T. Psychological safety influences relationship behavior. (Report). Corrections Today, 2011, 73, 1, s. 60–61.

8. Guillemin, F., Bombardier, C., Beaton, D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 1993, 46, 12, s. 1417–1432.

9. Havrdová, Z., Šolcová, I. The Relationship Between Workplace Civility Level and the Experience of Burnout Syndrome Among Helping Professionals. In Essential notes in psychiatry [on line]. Rijeka, InTech. 2012. [cit. 2014-05-12]. Dostupné na www: http://www.intechopen.com/books/essential-notes-in-psychiatry/work-place-civility-and-mental-health-by-helping-professionals.

10. Havrdová, Z., Šolcová, I., Hradcová, D., Rohanová, E. Kultura organizace a syndrom vyhoření. Československá psychologie, 2010, 54, 3, s. 235–248.

11. Idris, M. A., Dollard, M. F. Y. Psychosocial safety climate, emotional demands, burnout, and depression: Alongitudinal multilevel study in the Malaysian private sector. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 2014, 19, 3, s. 291–302.

12. Ježorská, Š., Merz, L. Is There A Link Between Job Satisfaction And Burnout? In SGEM Conference on Psychology & Psychiatry, Sociology & Healthcare, Education Conference Proceedings, Volume I. Sofia: STEF92 Technology Ltd, 2014, s. 225–231.

13. Kark, R., Carmeli, A. Alive and creating: the mediating role of vitality and aliveness in the relationship between psychological safety and creative work involvement. J. Organ. Behav., 2009, 30, 6, s. 785–804. doi:10.1002/job.571.

14. Kebza, V., Šolcová, I. Současné sociální změny, jejich důsledky a syndrom vyhoření. Československá psychologie, 2013, 57, 4, s. 329–341.

15. Kortum, E., Leka, S., Cox, T. Psychosocial Risks and Work-Related Stress in Developing Countries: Health Impact, Priorities, Barriers and Solutions. International journal of occupational medicine and environmental health, 2010, 23, 3, s. 225–238. doi: 10.2478/v10001-010-0024-5.

16. Leiter, M. P., Laschinger, H. K. Relationships of work and practice environment to professional burnout: testing a causal model. Nursing Research, 2006, 55, 2, s. 137–146.

17. Li, J., Zhang, M., Loerbroks, A., Angerer, P., Siegrist, J. Work stress and the risk of recurrent coronary heart disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern. J. Occup. Med. Environment. Health, 2015, 28, 1, s. 8–19.

18. Moghaddasi, J., Mehralian, H., Aslani, Y., Masoodi, R., Amir, M. Burnout among nurses working in medical and educational centers in Shahrekord, Iran. Iranian J Nursing Midwifery Res, 2013, 18, 4, s. 294–297.

19. Moustaka, E., Malliarou, M., Sarafis, P., Konstantinidis, T., Manolidou, Z. Burnout in Nursing Personnel in a Regional University Hospital [on line]. BMM, 2009, 12, 1, s. 1–7. [cit. 2015-01-20]. Dostupné na www: http://www.scopemed.org/fulltextpdf.php?mno=39364.

20. Nahrgang, J. D., Morgeson, F. P., Hofmann, D. A. Safety at work: a meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes.The Journal of Applied Psychology, 2011, 96, 1, s. 71–94.

21. Panunto, M. R., Guirardello, E. B. Professional nursing practice: environment and emotional exhaustion among intensive care nurses. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem [online]. 2013, 21, 3, s. 765–772. [cit. 2014-09-03]. Dostupné na www: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-11692013000300765&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en.

22. Pelcák, S., Tomeček, A. Syndrom vyhoření – psychické důsledky výkonu práce expedienta. Praktické lékárenství [on line]. 2011, 11, 7, s. 87–90. [cit. 2013 - 9-8]. Dostupné na www: http:// solen.cz/pdfs/lek/2011/02/10.pdf.

23. Poghosyan, L., Clarke, S., Finlayson, M., Aiken, L. Nurse burnout and quality of care: cross-national investigation in six countries. Research in Nursing and Health. [on line]. 2010, 33, 4, s. 288–298. [cit. 2014-03-02]. Dostupné na www: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2908908/pdf/nihms215130.pdf.

24. Richter, G., Gruber, H., Friesenbichler, H., Uscilowska, A., Jančurová, L., Konova, D., Hanáková, E. Psychická zátěž. Identifikace a vyhodnocování rizik; navrhovaná opatření. [on line]. 2010. [cit. 2014-03-02]. Dostupné na www: http://www.issa.int/details?uuid=4a828637-75bd-4048-82e5-d3712b16197d.

25. Schaefer, H. G., Helmreich, R. L., Scheideggar, D. Human factors and safety in emergency medicine. Resuscitation, 1994, 28, 3, s. 221–225.

26. Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E. The Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey. In Maslach, C., Jackson, S.E., Leiter, M. P. (Eds.), Maslach Burnout Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996.

27. Schein, E. H. How can organizations learn faster? The challenge of entering the green room. Sloan Management Review, 1993, 34, s. 85–92.

28. Schein, E., Bennis, W. Personal and Organizational Change through Group Methods. New York: Wiley, 1968, 376 s.

29. Schepers, J., Jong, A. D., Wetzels, M., Ruyter, K. D. Psychological Safety and Social Support in Groupware Adoption: A Multi-Level Assessment in Education. Computers & Education. [on line]. 2008, 51, 2, s. 757–775. [cit. 2014-02-24]. Dostupné na www: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/.

Labels

Hygiene and epidemiology Hyperbaric medicine Occupational medicine

Article was published inOccupational Medicine

2016 Issue 1-2-

All articles in this issue

- Grave diseases in senior subjects and vertigo

- Hearing loss in men and women working at risk and outside it in the Moravian-Silesian Region

- Analysis of occupational diseases in Slovakia in 2005–2014 also viewed from aspect of the risk work category

- Screening of ear in adults by questionnaire

- Impact of skin temperature on the screening electromyography results within the occupational medical examinations

- Professional risks on bladder carcinoma – overview of issues and pilot study results

- The application of treatment with ionized oxygen in occupational medicine

- The relationship between psychological safety and burnout among nurses

- Occupational Medicine

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- The application of treatment with ionized oxygen in occupational medicine

- Impact of skin temperature on the screening electromyography results within the occupational medical examinations

- The relationship between psychological safety and burnout among nurses

- Screening of ear in adults by questionnaire

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career