-

Medical journals

- Career

ScreenPro FH – Screening Project for Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Central, Southern and Eastern Europe: Basic Epidemiology

Authors: Richard Češka 1; Tomáš Freiberger 2,3; Andrey V. Susekov 4; György Paragh 5; Željko Reiner 6; Lale Tokgözoğlu 7; Katarína Rašlová 8; Maciej Banach 9; Branislav Vohnout 8,11; Andrzej Rynkiewicz 12; Assen Goudev 13; Gheorghe-Andrei Dan 14; Dan Gaiţă 15; Belma Pojskić 16; Ivan Pećin 6; Meral Kayıkçıoğlu 17; Olena Mitchenko 18; Marat V. Ezhov 19; Gustavs Latkovskis 20; Žaneta Petrulionienė 21; Zlatko Fras 22; Nebojsa Tasić 23; Erkin M. Mirrakhimov 24; Tolkun Murataliev 24; Alexander B. Shek 25; Vladimír Tuka 1; Alexandros D. Tselepis 26; Elie M. Moubarak 27; Khalid Al Rasadi 28

Authors‘ workplace: Paul Stradins Clinical University Hospital, Riga, Latvia ; Third Department of Medicine – Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism of the First Faculty of Medicine, Charles Universit and General University Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic 1; Molecular Genetics Lab, Centre for Cardiovascular Surgery and Transplantation, Brno, Czech Republic 2; Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic 3; Department of clinical Pharmacology and therapeutics, Academy for Postgraduate Education, Ministry of Health, Russian Federation 4; Institute of Internal Medicine, University of Debrecen Faculty of Medicine, Debrecen, Hungary 5; Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Metabolic Diseases, School of Medicine University of Zagreb, University Hospital Center Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia 6; Department of Cardiology, Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey 7; Coordination Center for Familial Hyperlipidemias, Slovak Medical University, Bratislava, Slovakia 8; Department of Hypertension, Medical University of Lodz, Lodz, Poland 9; Institute of Nutrition, FOaZOS, Slovak Medical University, Bratislava, Slovakia 11; Department of Cardiology and Cardiosurgery, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Warmia and Mazury, Olsztyn, Poland 12; Queen Giovanna University Hospital, Sofia, Bulgaria 13; University of Medicine Carol Davila, Colentina University Hospital, Bucharest, Romania 14; Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases, University of Medicine & Pharmacy Victor Babes, CardioPrevent Foundation Timisoara, Romania 15; Cantonal hospital, Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina 16; Cardiology Department, Ege University Medical School, Lipid Clinic, Izmir, Turkey 17; Institute of Cardiology, AMS Ukraine Dyslipidemia Department, Kiev, Ukraine 18; Russian Cardiology Research and Production Center, Moscow, Russian Federation 19; Latvian Institute of Cardiology and Regenerative Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Latvia 20; Centre of Cardiology and Angiology, Vilnius University Hospital Santariskiu Klinikos, of Cardiology and Angiology, Vilnius, Lithuania 21; Division of Internal Medicine, Preventive Cardiology Unit and Medical Faculty, University of Ljubljana, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Slovenia 22; Cardiovascular research Centre, Cardiovascular Institute “Dedinje”, Belgrade, Serbia 23; National Centre of Cardiology and Therapy named after academician Mirsaid Mirrakhimov, Kyrgyz State Medical Academy naved after I. K. Akhunbaev, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan 24; Republican Specialized Center of Cardiology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan 25; Department of Chemistry, University of Ioannina, Atherothrombosis Research Centre, Ioannina, Greece 26; LDL apheresis Centre, Dahr El Bachek Government University Hospital – DGUH, Roumieh – Lebanon 27; College of Medicine and Health Science at Sultan Qaboos University, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat, Oman 28

Published in: Vnitř Lék 2017; 63(1): 25-30

Category: Original Contributions

Overview

Introduction:

Despite great recent progress, familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is still underestimated, under-diagnosed and thus undertreated worldwide. We have very little information on exact prevalence of patients with FH in the Central, Eastern and Southern Europe (CESE) region. The aim of the study was to describe the epidemiological situation in the CESE region from data available.Methods:

All local leaders of the ScreenPro FH project were asked to provide local data on (a) expert guess of FH prevalence (b) the medical facilities focused on FH already in place (c) the diagnostic criteria used (d) the number of patients already evidenced in local database and (e) the availability of therapeutic options (especially plasma apheresis).Results:

With the guess prevalence of FH around 1 : 500, we estimate the overall population of 588 363 FH heterozygotes in the CESE region. Only 14 108 persons (2.4 %) were depicted in local databases; but the depiction rate varied between 0.1 % and 31.6 %. Only four out of 17 participating countries reported the the LDL apheresis availability.Conclusion:

Our data point to the large population of heterozygous FH patients in the CESE region but low diagnostic rate. However structures through the ScreenPro FH project are being created and we can hope that the results will appear soon.Key words:

diagnosis – epidemiology – familial hypercholesterolemia – screeningIntroduction

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is a genetic disorder with well-known genetic transmission and clinical course [1]. Despite great recent progress, FH is still underestimated, under-diagnosed and thus undertreated [2]. Furthermore it represents a significant healthcare challenge as a common risk factor for the premature development of coronary heart disease [3].

The prevalence of FH in a given population can be only estimated. The estimated global number of patients with FH is at least 15 million people [4]. FH is an autosomal dominant disease that occurs naturally in two forms: homozygous and heterozygous. FH homozygotes are rare and their frequency in the general population is about 1 : 1 000 000. In specific populations the “founder effect” increases the prevalence (i.e. increased frequency of FH or a predominant mutation in a specific population because a new population was founded by a very small subset of the original population “bottle necking”) [5]. The population prevalence of FH homozygotes based on the founder effect is between 1 : 10 000 and 1 : 100 000. The highest prevalence rates are found in the Afrikaner population in South Africa (1 : 10 000), and high rates have also been observed in French Canadians (mainly in the province of Quebec). In Europe, the highest prevalence of homozygous FH is in north-western Europe. In heterozygotes, the highest prevalence is found also in the Afrikaner population in South Africa (as high as 1 : 70) and in French Canadians (1 : 270) [6–8]. The Netherlands reports an prevalence of 1 : 300–1 : 400 [9]. We have very little information on exact prevalence of patients with FH in the Central, Eastern and Southern Europe (CESE) region. With regard to the Czech population from CESE region (which is similar to the American population), the more commonly cited heterozygote prevalence of 1 : 500 is still valid [1]. There are other populations with a higher prevalence of FH that have not yet been precisely specified via epidemiological investigations (e.g. Lithuanian Jews, the Lebanese) [10,11]. The prevalence is also higher in preselected population, e.g. in the setting of coronary care unit [12].

The aim of the study was to map the epidemiological situation in the CESE region.

Methods

ScreenPro FH project

The ScreenPro FH Project is an international network project aiming at improving complex care – from timely screening, through diagnosis to up-to-date treatment of familial hypercholesterolemia in Central, Eastern and Southern Europe including some countries of the Middle Asia.

Data acquisition

All local leaders were asked to provide local data on

- expert guess of FH prevalence

- the medical facilities focused on FH already in place

- the diagnostic criteria

- the number of patient already in database

- the availability of therapeutic options (especially plasma apheresis)

Statistics

We used descriptive statistics only. Relative rates were used where appropriate.

Results

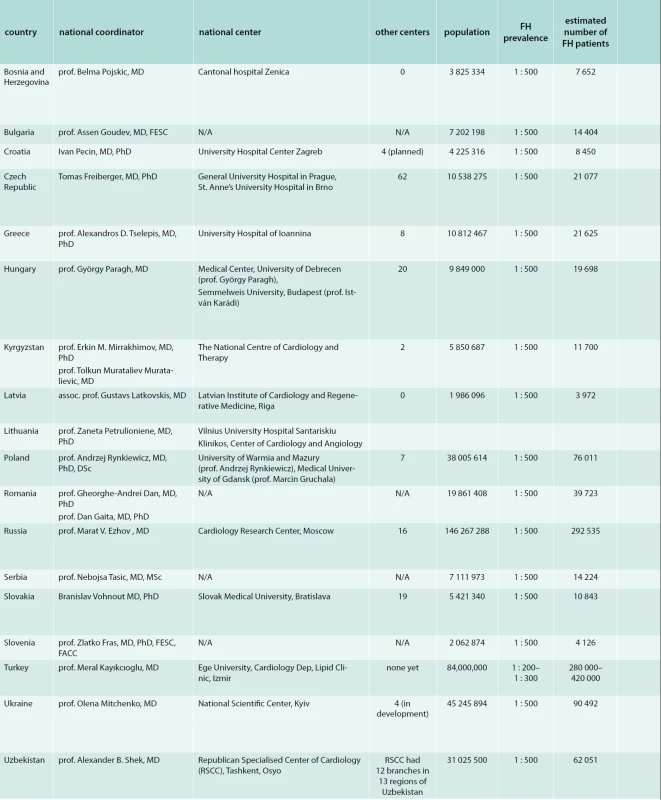

The total population of the CESE regions counts 430 361 839 persons. In the majority of states the guess prevalence of FH is around 1 : 500, which translates to an overall population of 588 363 FH heterozygotes. Nevertheless only 14 108 persons (2.4 %) are evidenced in local databases, where the diagnostic rate varies considerably between countries from 0.1 % to 31.6 % (tab).

1. Overview of participating countries

<b>FH</b> – familial hypercholesterolemia <b>N/A</b> – not available All countries used the Dutch lipid clinic network diagnostic criteria as primary diagnostic tool. Besides these MedPed criteria are being used in the Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia and the Simon Broome diagnostic criteria are being used in Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine.

Only four countries reported the availability of LDL apheresis (Czech Republic, Greece, Russia and Turkey).

Discussion

The prevalence of patients with heterozygous FH was estimated mostly as 1 : 500, as the prevalence in community derived from symptomatic FH patients (from hospital patients, registries, and from models estimating also homozygous FH [13–16]. Nevertheless the epidemiological studies from unselected populations in last years, that combined also genetic analysis and cascade screening, led to higher FH prevalence. In a huge unselected Danish general population the prevalence of FH was 1 : 223 FH was defined as Dutch lipid clinic network score higher than 5 [17]. The data derived from United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys led to an estimated US prevalence of probable/definite FH 1 : 250. Probable and definite diagnosis was defined according to Dutch lipid clinic network score 6–8 points and more than 8 points, respectively. The probable FH prevalence was 1 : 267 and definite 1 : 4 023. In China the estimated FH prevalence was 1 : 357 [18] and in Australia 1 : 353 and 1 : 229 [19]. In Poland, one of the countries from the CESE region, the pooled data from several studies the FH prevalence was also higher than expected: 1 : 248 [20]. These results correspond to the finding of Wald et al, who performed a FH screening among children during routine immunization visits. In these 1–2 years old children detected newly diagnosed FH in 4 in 1 000 children, which translates to a prevalence rate of 1 : 250 [21]. If we assume this higher prevalence, this would lead to doubling the number of patients affected by FH in the CESE region.

In the countries of the CESE region the predominantly used diagnostic criteria are Dutch lipid clinic network diagnostic criteria. The genetic testing is not necessary for the diagnosis of FH, as in approximately 20 % of patients with a clinical FH diagnosis we are unable to find a genetic mutation [3]. Nevertheless when a genetic mutation is demonstrated the diagnosis of FH is established [1]. On the other hand not all patients with a heterozygous FH mutation have LDL-cholesterol high enough to make the clinical diagnosis [1]. That is why the recommended screening criteria in the ScreenPro FH project are the Dutch lipid clinic network diagnostic criteria, which combines both possibilities: genetic and clinical diagnosis.

The number of patients already followed in databases is very low from the target FH population (2.4 %) and varies from country to country. Unfortunately this is in accordance with the worldwide situation. In most countries the estimated diagnosed FH is less than 1 % from the number of FH patients predicted from the prevalence of 1 : 500 [2]. The highest diagnosis rates are in the Netherland and Norway, where the diagnostic process received a governmental support and in countries with dedicated physicians [1].

LDL apheresis is indicated in homozygous FH patients and severe heterozygous FH patients [1]. LDL apheresis is available only in few countries (Czech Republic, Greece, Russia, Turkey).

Conclusion

Our data point out to the large population of heterozygous FH patients in the CESE region but low diagnostic rates. However structures through the ScreenPro FH project are being created and we can hope that the results will appears soon.

Financial support

To increase our financial resources we´ve applied for the IAS independent grant: IAS/Pfizer IGLC Grant Request: Lipid Management in High-Risk Patients.

The project is financially supported by Amgen and Sanofi.

Local activities in different countries are also supported by local grants and sponsors.

Conflict of interest

Authors expressed these conflicts of interest:

- grants/research supports – Amgen, Sanofi

- honoraria or consultation fees – MSD, Bayer, Aegerion, Amgen, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, AOP orphan, Teva, Pfizer, Servier Laboratories, Abbott Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Berlin Chemie, novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mylan, Krka

- participation in a company sponsored speaker’s bureau – MSD, Bayer, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer

- other support – advisory boards, clinical studies – MSD, Bayer, Aegerion, Amgen, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, AOP Orphan, Pfizer, Teva, Regeneron

prof. Andrey V. Susekov, MD

asus99@mail.ru

Department of clinical Pharmacology and therapeutics, Academy for Postgraduate Education, Ministry of Health,

Russian Federation

www.rmapo.ru

Doručeno do redakce 22. 12. 2016

Sources

1. Ceska R, Freiberger T, Vaclova M et al. Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Triton: Praha 2015. ISBN 978–80–7387–953–2.

2. Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J 2013; 34(45): 3478–3490a. Dostupné z DOI: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht273>.

3. Pejic RN. Familial hypercholesterolemia. Ochsner J 2014; 14(4): 669–672.

4. Watts GF, Juniper A, van Bockxmeer F et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia: a review with emphasis on evidence for treatment, new models of care and health economic evaluations. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2012; 10(3): 211–221. Dostupné z DOI: <http://10.1111/j.1744–1609.2012.00272.x>. Erratum in Int J Evid Based Healthc 2012; 10(4): 419.

5. Goldberg AC, Hopkins PN, Toth PP et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia: screening, diagnosis and management of pediatric and adult patients: clinical guidance from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol 2011; 5(3 Suppl): S1-S8. Dostupné z DOI: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2011.04.003>.

6. Steyn K, Goldberg YP, Kotze MJ et al. Estimation of the prevalence of familial hypercholesterolaemia in a rural Afrikaner community by direct screening for three Afrikaner founder low density lipoprotein receptor gene mutations. Hum Genet 1996; 98(4): 479–484.

7. Davignon J, Roy M. Familial hypercholesterolemia in French-Canadians: taking advantage of the presence of a “founder effect”. Am J Cardiol 1993; 72(10): 6D-10D.

8. Betard C, Kessling AM, Roy M et al. Molecular genetic evidence for a founder effect in familial hypercholesterolemia among French Canadians. Hum Genet 1992; 88(5): 529–536.

9. Umans-Eckenhausen MA, Defesche JC, Sijbrands EJ et al. Review of first 5 years of screening for familial hypercholesterolaemia in the Netherlands. Lancet 2001; 357(9251): 165–168.

10. Durst R, Colombo R, Shpitzen S et al. Recent origin and spread of a common Lithuanian mutation, G197del LDLR, causing familial hypercholesterolemia: positive selection is not always necessary to account for disease incidence among Ashkenazi Jews. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 68(5): 1172–1188.

11. Edwards JA, Bernhardt B, Schnatz JD. Hyperlipidemia in a Lebanese community: difficulties in definition, diagnosis and decision on when to treat. J Med 1978; 9(2): 157–182.

12. Pang J, Poulter EB, Bell DA et al. Frequency of familial hypercholesterolemia in patients with early-onset coronary artery disease admitted to a coronary care unit. J Clin Lipidol 2015; 9(5): 703–708. Dostupné z DOI: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2015.07.005>.

13. Austin MA, Hutter CM, Zimmern RL et al. Genetic causes of monogenic heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: a HuGE prevalence review. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 160(5): 407–420.

14. Marks D, Thorogood M, Neil HA et al. A review on the diagnosis, natural history, and treatment of familial hypercholesterolaemia. Atherosclerosis 2003; 168(1): 1–14.

15. Hopkins PN, Toth PP, Ballantyne CM et al. Familial Hypercholesterolemias: Prevalence, genetics, diagnosis and screening recommendations from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol 2011; 5(3 Suppl) :S9-S17.Dostupné z DOI: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2011.03.452>.

16. Neil HA, Hammond T, Huxley R et al. Extent of underdiagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia in routine practice: prospective registry study. BMJ 2000; 321(7254): 148.

17. Benn M, Watts GF, Tybjaerg-Hansen A et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia in the danish general population: prevalence, coronary artery disease, and cholesterol-lowering medication. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(11): 3956–3964. Dostupné z DOI: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012–1563>.

18. Shi Z, Yuan B, Zhao D et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia in China: Prevalence and evidence of underdetection and undertreatment in a community population. Int J Cardiol 2014; 174(3): 834–836. Dostupné z DOI: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.165>.

19. Watts GF, Shaw JE, Pang J et al. Prevalence and treatment of familial hypercholesterolaemia in Australian communities. Int J Cardiol 2015; 185 : 69–71. Dostupné z DOI: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.027>.

20. Pajak A, Szafraniec K, Polak M et al. Prevalence of familial hypercholesterolemia: a meta-analysis of six large, observational, population-based studies in Poland. Arch Med Sci 2016; 12(4): 687–696. Dostupné z DOI: <http://dx.doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2016.59700>.

21. Wald DS, Bestwick JP, Morris JK et al. Child-Parent Familial Hypercholesterolemia Screening in Primary Care. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(17): 1628–1637.

Labels

Diabetology Endocrinology Internal medicine

Article was published inInternal Medicine

2017 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Predatory journals: how their publishers operate and how to avoid them

- Closure of the left atrial appendage by means of the AtriClip System

- Treatment of HCV genotype 2 infection

- A contribution to the differential diagnostics of sclerosing cholangitides

- The importance of evaluating the effectiveness of the ventilation VE/VCO2 slope in patients with heart failure

- 2nd Prague European Days of Internal Medicine

- ScreenPro FH – Screening Project for Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Central, Southern and Eastern Europe: Basic Epidemiology

- ScreenPro FH – Screening Project for Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Central, Southern and Eastern Europe: Rationale and Design

- Appendix diagnostica – Familial hypercholesterolemia diagnostic criteria

- Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- Internal Medicine

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Closure of the left atrial appendage by means of the AtriClip System

- The importance of evaluating the effectiveness of the ventilation VE/VCO2 slope in patients with heart failure

- Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- A contribution to the differential diagnostics of sclerosing cholangitides

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career