-

Medical journals

- Career

Suddenly deceased young individuals autopsied at the Department of forensic medicine, Brno – analysis

Authors: M. Zeman 1; M. Sepši 2; T. Vojtíšek 1; M. Šindler 1

Authors‘ workplace: Masaryk University, St. Anne’s Faculty Hospital, Department of Forensic Medicine, Brno 1; University Hospital Brno, Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiology 2

Published in: Soud Lék., 57, 2012, No. 3, p. 44-47

Category: Original Article

Overview

Determination of the cause of death in sudden deaths of young people is a relatively common problem in routine medical practice. In cases of poor or negative morphologic findings at autopsy and poor or negative test results from laboratory, diagnostic quandary can occur. The grant project IGA MZ CR (Internal Grant Agency of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic) targets cases of the sudden deaths of young people under 40 years of age, where, even after an autopsy performed, and other laboratory examinations at the Department of Forensic Medicine are completed, it fails to detect the exact cause of death and death as a possible etiology is supposed malignant cardiac arrhythmias. The project aims to introduce a genetic analysis of these sudden deaths of individuals and determine the frequency of genetic pathologies related to malignant arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies, as well as clinical examination of direct relatives of the deceased by cardiologist, focusing on the identification of families at risk of sudden cardiac death. This examination and identification of causes of death will offer bereaved relatives prevention of sudden death and appropriate therapy. This article summarizes a retrospective analysis of sudden deaths of young people with a focus on monitoring diagnosed and unspecified cause of death and an analysis by age, gender and time of day.

In the age range 1–40 years, the authors found less than 15 % of sudden death cases where it was not possible after performing autopsies or laboratory examinations to establish a clear cause of death. In such cases, it is considered category of hereditary channelopathies such as largely the congenital long-QT syndromes as possible etiology of sudden cardiac death. The authors consider useful to offer cardiological investigation to the relatives of the deceaseds, as well as genetic analysis of sudden deaths (molecular autopsy) and their relatives, which in the Czech Republic is not usually performed.Keywords:

sudden and unexpected death – malignant cardiac arrhythmias – LQT syndrome – molecular autopsySudden cardiac death (SCD) is defined as death from an unexpected circulatory arrest, usually due cardiac arrhythmia, occurring within an hour of the onset of symptoms (1). Depending on authors, when speaking of Sudden cardiac death in the young (SCDY),“young” is defined as those up to range from 25 till 40 years (2). Estimates of the incidence of SCDY (not including infants) vary broadly from 0.6 to 6.2 per 100 000 persons (2,3).

In our article SCDY cases in which was recorded the negative autopsy and laboratory findings, were monitored together with cases of SIDS, where possibility of cardiac etilogy cannot be ruled out. Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is defined as the sudden death of an infant less than 1 year of age that cannot be explained after a thorough investigation is conducted, including an autopsy, death scene evaluation, and review of the clinical history. The incidence of SIDS ranges from 50 to 100 in 100 000 (4). It is assumed that 10 % to 15 % of SIDS deaths are associated with functional cardiac ion channelopathy gene variants (5). As for the analysis of the causes SCDY, there are many published studies that show significantly different results. It is possible to find information on the occurrence of negative autopsy findings in SCDY cases for people under 1 year of age at 7 % (n = 20), 1 to 21 years of age in 10 % (n = 50) (6). Burke reports negative findings even at 30 % of SCDY in the age group 14 to 20 years (n = 60) and 21 % in the age group 21 to 30 years (n = 229) (7). In a survey of Winkel et al. were presented autopsy results of 469 sudden unexpected death cases, 314 cases (age 1–35) were attributed to sudden cardiac death. In 29 % of autopsied sudden unexpected deaths, no cause of death was found, suggesting a primary arrhythmogenic cause of death (8). In perhaps 10 % of childhood (commonly accepted as the first two decades of life) sudden death (SD) cases, a lethal dysrhythmia is a primary event and occurs in a structurally normal heart (9). In such cases, it is considered category of hereditary diseases such as the congenital long-QT syndromes (LQTS), catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), and Brugada syndrome as a possible etiology of SCD. Estimated prevalence rates of these conditions range from 1 per 2500 for the LQTS (2).

Behr et al. in 2003 documented that at 22 % of families with 32 sudden unexplained deaths has been shown inherited cardiac disease, primarily features suggestive of the long QT syndrome (10), Tan’s study indicates the occurrence of identifiable cardiac channelopathy following a clinical assessment at 28 % of families with sudden unexplained deaths of young people (10). According to other studies, up to 50 % of cardiac causes in children dying during exercise are idiopathic arrhythmias with apparently normal heart at autopsy (11).

AIM OF THE STUDY

In the article the authors focus on the presentation of a retrospective analysis of data relating to cases of sudden deaths of young individuals, in whom autopsy was performed at the Department of Forensic Medicine in Brno. This analysis was prepared under a grant project of the Internal Grant Agency of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic, concerning the possibility of genetic testing in cases of sudden and unexpected deaths of young people under 40 years of age. In this group it is possible to find cases where, even after the use of all currently available investigative techniques that the Department of Forensic Medicine offers, we fail to determine the exact cause of death. Among the possible etiology of deaths are malignant cardiac arrhythmias. Genetic analysis of sudden deaths of individuals targeted for this pathology does not belong in the Czech Republic to a standard examination. The aim of this project is not only to establish the diagnostic measures to determine the frequency of genetic pathologies related to malignant arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy but also direct clinical examination of relatives of deceased by a cardiologist.

METHODS

The project of sudden deaths monitoring in the region of South Moravia, Czech Republic ( an area of about 2 million inhabitants) involves the cooperation of a forensic physician (Department of Forensic Medicine, St. Anne’s University Hospital Brno), a pathologist, a geneticist (Department of Medical Genetics, Faculty Hospital Brno, Department of Pathological Physiology of Faculty of Medicine of Masaryk University in Brno,) and a cardiologist (Department of Internal Cardiology Medicine of Faculty Hospital Brno). We examined all deceased that are under the age of 40, but found no pathologic or toxicologic evidence explaining the cause of death, most commonly with autopsy diagnosis of acute heart failure. We focus on sudden unexplained deaths, often unwitnessed. Another group of patients, that is of our interest, and is suitable for a genetic examination, are those with macroscopic picture of cardiomyopathy and a supposed genetic linkage (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, dilated cardiomyopathy). We exclude patients with presence of measurable blood alcohol levels and positive toxicology examination, which could have a causal connection with the death, atherosclerosis as a leading cause of death and with positive microbiologic and/or virologic examinations. After these exclusions, the final group of deceased are genetically screened with a focus on gene mutations associated with LQT syndrome – KCNQ1, KCNH2, KCNE1, SCN5A, KCNE2 and ANK2. At the same time, direct blood relatives of the deceased are offered a clinical cardiological and genetic examination.

RESULTS

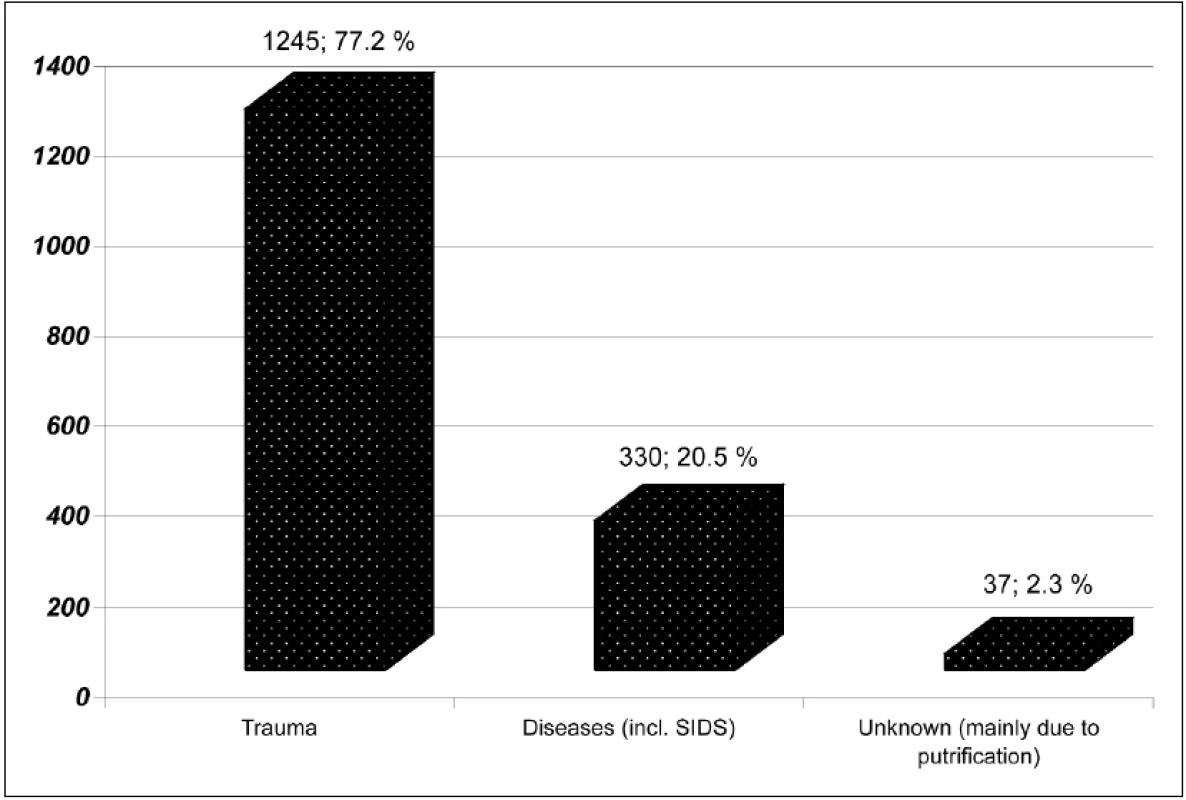

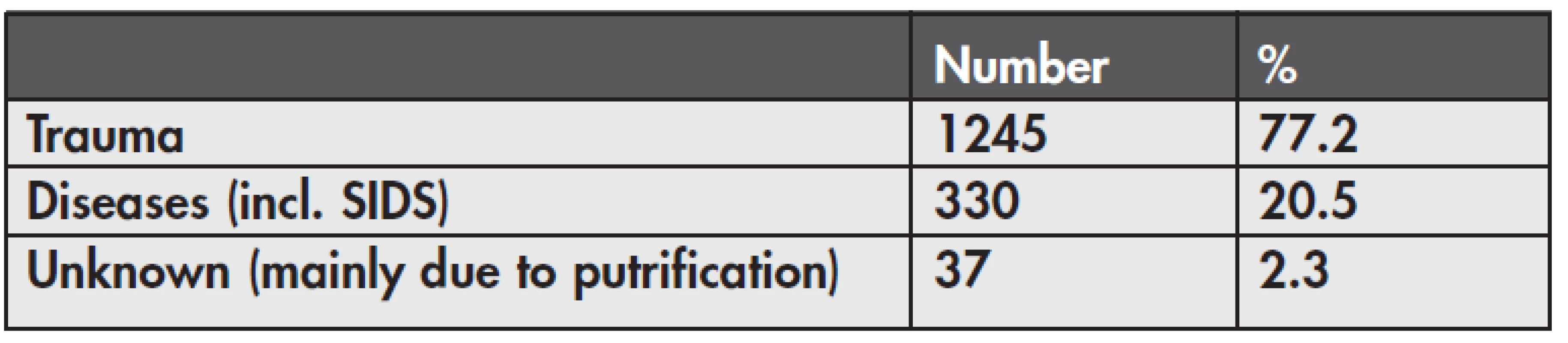

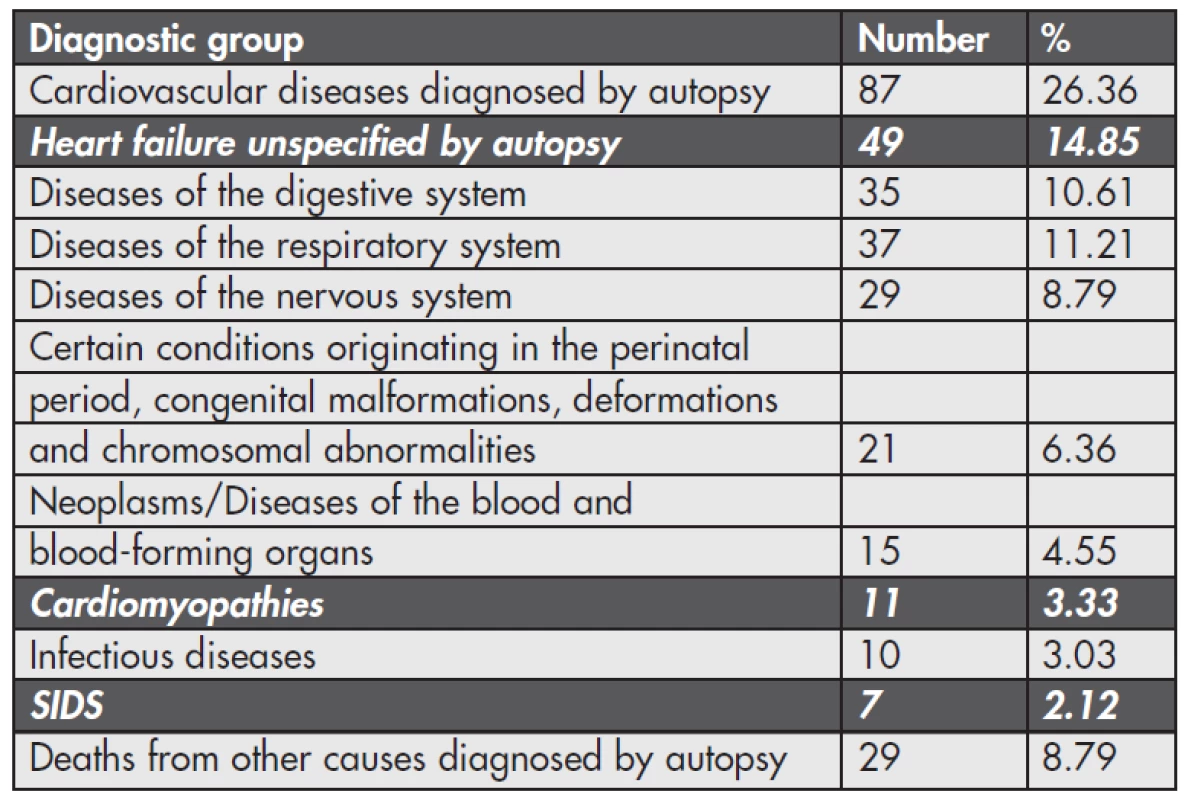

Retrospective analysis: We have focused on cases of deaths from 2007 to 2011 (January to October). Over this period an autopsy was performed in total of 12,314 deaths. 1612 of these deaths were on individuals that were under 40-years of age. Results of the main pathological causes of death (N = 330) in the diagnostic groups of the deceased are shown in Table 1 (and Figure 1). As shown in Table 2, the total number of studied cases during the four years is 67, which is 20.3 %, while 14.85 % (49 cases) accounted for heart failure unspecified by autopsy, 3.33 % (11 cases) for cardiomyopathies and 2.12 % (7 cases) for SIDS. These three groups were then analyzed separately.

2. Suddenly deceased persons under 40 years of age.

Due to the selected genetic diagnosis particularly targeted at LQT the most important in terms of analysis was the largest subgroup of heart failure unspecified by autopsy. Of the 49 persons 37 persons were male and 12 female. Arithmetic average age, when the death occurred is 32.45 years, median 35 years, minimum age 14 years, maximum 40 years. Figure 2 captures the distribution by the number of cases of deaths in this group, depending on time of day when the death occurred. Any physical activity in the period immediately preceding death was also noted. It was found that in 23 cases death occurred during sleep or idle state, in 8 cases was the detection of past history of physical activity at the time of death. In 18 cases this could not be determined because of missing clinical history. We would like to emphasize that persons with toxicological finding, which would have an immediate causal relationship to death, were excluded from the target file, and there were a total of 3 cases of positive detection of THC in urine. In 2 cases the level of blood alcohol was in the interval up to 0.5 g/kg, in 4 cases ranging from 0.5 to 1.0 g/kg, in 2 cases from 1.0 to 1.5 g/kg and in 2 cases in the interval from 1.5 to 2.0 g/kg. In 29 cases of deaths toxicological examination was entirely negative (alcohol, drugs or their metabolites).

2. SCDY cases (with no autopsy findings) depending on time of day when the death occurred.

In the group of cardiomyopathies (n = 11) were 7 deaths male and 3 female. Total detected 3 cases of dilated cardiomyopathy, 1 case of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 1 case of ARVC, endocardial fibroelastosis was recorded in the event of 1 death. 5 cases were diagnosed as “other” cardiomyopathies.

In the diagnosis of SIDS as a cause of death (n = 7), infants were 4 male and 3 female.

Prospective investigations: After an autopsy and a histological and toxicological examination, there were remains 35 unexplained deaths (this is due to the fact that the genetic sample was not available in all 67 cases) in individuals that died under the age of 40. From 19 relatives we got agreements with molecular autopsy, by the end of October 2011 we examined biological samples of these deceased persons for genes for LQT: KCNQ1, KCNH2, KCNE1, SCN5A, KCNE2 and ANK2. We found some common polymorphisms - at SCNA gene we found G87A, IVS9-3c>a, A1673G(H558R), G3183A, IVS25+65g>a and C5457T. Genetic testing is currently in progress and its results will be the subject of further publications. Relatives, who were willing to participate (together 27 members from 10 families by the end of 2010) had cardiology examination – with normal output: no clinical significance for cardiac pathology.

CONCLUSIONS

In the age range 1–40 years, we found less than 15 % of SD cases where it was not possible after performing autopsies or laboratory tests to establish a clear cause of death. In the literature slightly lower figure – 5–10 % was published (12). Approximately three quarters of our SCD set of people who died were male, which corresponds with other studies (12). As expected, most of these deaths occurred in the oldest group of individuals in the target file, ie 30–40 years. According to other authors, the risk of dying of SCD was 10 times higher for persons aged 30–35 years than for persons aged 1–10 years (8). The sudden and unexplained deaths of young people in our group occurred mostly at night or in early morning hours, mostly during sleep and physical rest. Recent analysis reported that only 5 % of SD were associated with significant physical exertion (10).

In analyzing the causes of sudden death in young individuals as a key search revealed an active effort to contact living relatives. The addition of family and personal history from relatives is important for diagnostic balance for the forensic expert. Clinical cardiological investigation of relatives of the deceaseds is still ongoing and the authors intend to publish its detailed results in the future. Until now, in relatives of SCD autopsied in Department of Forensic Medicine, Brno, cardiac pathology was not detected by clinical examination. In these negative findings the problems of sensitivity and specificity of ECG testing in asymptomatic cases of LQT syndrome could be also significant. However, we consider benefits to actively offer this test to relatives in the future. Also, genetic analysis of sudden deaths (molecular autopsy) and their relatives, which in the Czech Republic is not usually performed, according to the authors’ opinion, could mean significant benefits for the detection of potentially lethal diseases from cardiac causes in living people, as well as in the diagnostics in Forensic Medicine. Future possibilities would probably help to discover more genes responsible for sudden unexpected deaths. Although according to the literature genetic testing is recommended in similar cases, recent survey conducted mainly in European countries has shown a very limited application of genetic testing in SCD cases in forensic investigation, very often for financial reasons (12). According to our findings from the literature, even in the U.S. postmortem genetic testing is not covered by health insurance (2).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research sponsored by the research project of the Internal Grant Agency of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (IGA MH CZ) NR/1044-3. The authors sincerely thank to Mrs. Eva Martina Jones for her linguistic revision.

Address for correspondence:

MUDr. Martin Zeman

Department of Forensic Medicine

St. Anne’s Faculty Hospital, Brno

Tvrdého 2a, 602 00 Brno, Czech Republic

tel.: +420 543 426 542

fax: +420 543 426 519

e-mail: martin.zeman@fnusa.cz

Sources

1. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines VA SCD, Europace 2006, 8, 746.

2. Kaltman JR, Thompson PD, Lantos J, et al. Sreening for Sudden Cardiac Death in the Young. Circulation 2011; 123 : 1911–1918.

3. Maron BJ, Doerer JJ, Haas TS, Tierney DM, Mueller FO. Sudden deaths in young competitive athletes: analysis of 1866 deaths in the United States, 1980–2006. Circulation 2009; 119 : 1085–1092.

4. Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Kimball M, Tomashek KM, Anderson RN, Blanding S. US infant mortality trends attributable to accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed from 1984 through 2004: are rates increasing? Pediatrics. 2009; 123 : 533–539.

5. Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. Cardiomyopathic and channelopathic causes of sudden unexplained death in infants and children. Annu Rev Med 2009; 60 : 69–84.

6. Steinberger J et all. Causes of sudden unexpected cardiac death in the first two decades of life. Am J Cardiol 1996; 77, 11 : 992.

7. Burke AP, Farb A, Virmani R, Goodin J, Smialek JE. Sports-related and non-sports-related sudden cardiac death in young adults. American Heart Journal 1991; 121 : 568–575.

8. Winkel BG, Holst AG, Theilade J, et al. Nationwide study of sudden cardiac death in persons aged 1–35 years. European Heart Journal 2011; 32 : 983–990.

9. Fineschi V, Baroldi G, Silver MD. Pathology of the Heart and Sudden Death in Forensic Medicine. Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton; 2006 : 223.

10. Marcus FI, Chugh SS. Unexplained sudden cardiac death: an opportunity to identify hereditary cardiac arrhythmias. European Heart Journal 2011; 32 : 931–933.

11. Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A. Sudden cardiac death. Cardiovascular Pathology 2011; 10 : 211–218.

12. Allegue C, Gil R, Blanco-Verea A, et al. Prevalence of HCM and long QT syndrome mutations in young sudden cardiac death-related cases. Int J Legal Med 2011; 125 : 565–572.

Labels

Anatomical pathology Forensic medical examiner Toxicology

Article was published inForensic Medicine

2012 Issue 3-

All articles in this issue

- Primary and secondary complex suicide. A 30-year retrospective suicide

- The year 1989 and its reflection in the forensic medicine

- Suddenly deceased young individuals autopsied at the Department of forensic medicine, Brno – analysis

- Forensic toxicological implications of pleural effusion; an autopsy case of drug overdose

- Forensic Medicine

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Primary and secondary complex suicide. A 30-year retrospective suicide

- Suddenly deceased young individuals autopsied at the Department of forensic medicine, Brno – analysis

- Forensic toxicological implications of pleural effusion; an autopsy case of drug overdose

- The year 1989 and its reflection in the forensic medicine

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career