-

Medical journals

- Career

Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis: case report and review of literature

Authors: M. Ben Oun 1; M. Skraková 2; M. Paulovičová 3; A. Adamec 1; M. Vargová 1; M. Korbeľ 1

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Haematology and Transfusiology, Faculty of Medicine Comenius University and University Hospital, Bratislava, Slovakia, head A. Batorova, MD, PhD, prof. 2; Rádiologia, spol. s. r. o., Bratislava, Slovakia, head J. Bilický, MD, PhD, prof. 3; st Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Faculty of Medicine Comenius University and University Hospital, Bratislava, Slovakia, head M. Borovsky, MD, PhD, prof. 11

Published in: Ceska Gynekol 2020; 85(4): 254-258

Category:

Overview

Objective: An analysis of POVT (postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis) case, the importance of prompt diagnosis, antibiotic and anticoagulation therapy management with multidisciplinary team approach.

Design: A case report and literature review.

Setting: 1st Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Faculty of Medicine Comenius University and University Hospital, Bratislava, Slovakia.

Methods and results: Authors would like to draw attention to the pitfalls of diagnosis and treatment of postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis with combination of antibiotics and anticoagulants after uncomplicated vaginal delivery.

Conclusion: Due to potentially life-threatening postpartum complications such as sepsis and pulmonary embolism, prompt diagnosis and treatment of POVT are important. To detection of POVT are MRI and CECT associated with higher sensitivity and specificity compared to colour Doppler ultrasound. For symptomatic POVT many authors suggest anticoagulation for 3 to 6 months (until there is radiologically confirmed thrombus resolution) with the addition of antibiotics for 7 to 10 days (in the case of suspected infection). Multidisciplinary approach is important.

Keywords:

ovary – vein thrombosis – postpartum period – anticoagulation

INTRODUCTION

Postpartum Ovarian Vein Thrombosis (POVT) also termed puerperal ovarian vein thrombosis is a rare postpartum complication, with an estimated incidence of 1 : 600 – 1 : 2000 deliveries. It has been reported in approximately 0.05-0.18% of vaginal births and in 2% of caesarean section births [4, 18]. The first case of post partum ovarian vein thrombosis was described by Austin in 1956 [2].

POVT prompt diagnosis is important to prevent morbidity and mortality. Although it´s uncommon, it should be considered in patients presenting with pelvic or flank pain, fever, abdominal palpable mass and elevated inflammatory parameters [8]. However these symptoms are also suggestive of other diseases, such as appendicitis, pyelonephritis, urinary tract infection, adnexal torsion, puerperal endometritis and tubo-ovarian abscess, which can delay the POVT diagnosis. The recommended treatment is intravenous antibiotic therapy and anticoagulation. There are no specific guidelines for the duration of treatment. Therefore a multidisciplinary team approach is recommended [14].

The case of successfully treated right POVT in 34-year old patient on 3rd postpartum day and review of literature is presented in this article.

CASE PRESENTATION

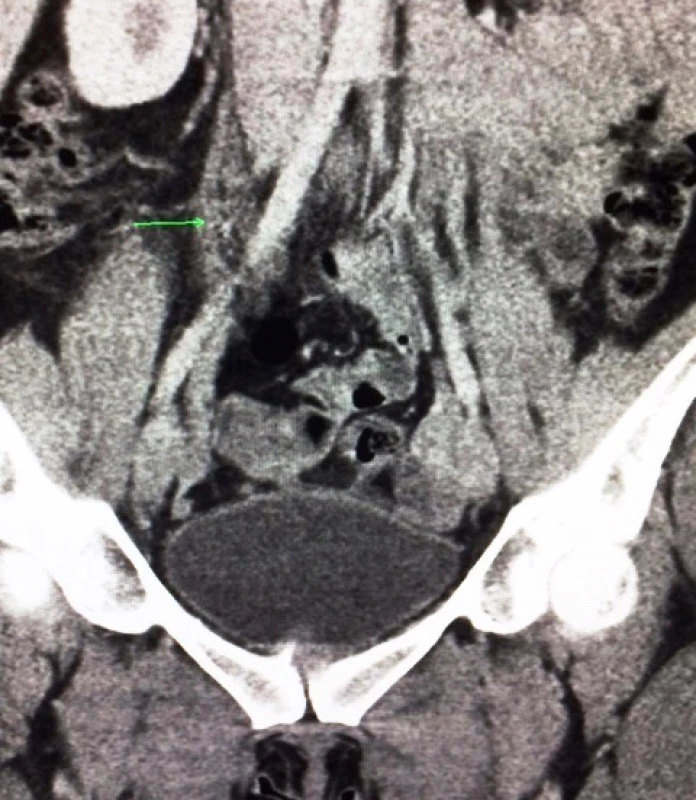

A 34-year old woman, (gravida 3, para 3) after uncomplicated vaginal delivery on the 3rd postpartum day, presented with persistent fever (temperature up to 40.2 °C), and complaining of aching right flank pain that was not associated with other constitutional symptoms. She had tenderness in the right lower quadrant with pain on palpation, other quadrants were free. Involution of uterus was adequate, without tenderness. There was no evidence of deep vein thrombosis in the lower extremities. Her obstetrical history included two term spontaneous vaginal deliveries with unremarkable antenatal and postpartum period. She was non-smoker, without significant past medical or surgical history, or family history of hematologic disorders, her body mass index (BMI) was 27.1. Laboratory investigations revealed elevated C reactive protein (CRP) 101.4 mg/dl (0–5), and white blood cell count was 11.4×109/l (6–11.0×109). A transabdominal ultrasound revealed a normal sized uterus, presence of non-homogeneous mass around the right adnexa sized 9×4 cm suspicious of adnexitis or pyo-salpinx without any free fluid, and splenomegaly. Patient was empirically treated with combination of intravenous amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid (1.2 g) and gentamicin (80 mg) every 8 hours. In followed 5 days fever persisted up to 38.4 °C, CRP rise up to 189.9 mg/l, procalcitonin (PCT) elevated to 0.922 ng/ml (< 0.5), white blood cell count was 11.29×109/l, platelet count 166×109/l, but pain decreased. Coagulability work-up revealed elevated D-Dimer (2.91 mg/l (> 0.0–0.47), fibrinogen 4.4 g/l (> 1.8–3.5), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) without deficit. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Genital tract culture revealed Lactobacillus jensenii, Veillonela montpelleirensis, alpha-haemolytic streptococci, and coagulase negative staphylococci (all sensitive to amoxicillin). Pelvic contrast enhancement computed tomography (CECT) demonstrated thrombosed dilated right ovarian vein up to 12 mm throughout its course with its junction to inferior vena cava, congestive enlarged right adnexa, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly at 8th postpartum day (Figure 1).

1. CECT 8th postpartum day: right ovarian vein thrombosis (green mark), congestive enlarged right adnexa, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly

Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) therapy was initiated with subcutaneous injection of nadroparin calcium (5,700 IU) 0.6 ml twice daily, with monitoring anti-Xa factor 3 hours following morning dose of LMWH after haematologist consultation. Anti-Xa value was (0.69). The patient was discharged 5 days later without abdominal pain and fever (afebrile), with decreased CRP to 13 mg/l and PCT to 0.051 ng/ml and anticoagulant therapy subcutaneous injection of nadroparin calcium forte (11,400 IU) once daily. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid therapy (orally) continued to 10 days.

Anticoagulation therapy was prolonged up to 3 months with subcutaneous injection of nadroparin calcium forte (11,400 IU anti-X) 0,6 ml once daily, which was changed after 3 weeks to enoxaparine sodium 0,6 ml (6,000 IU anti-X) twice daily, due to skin allergic reaction. Due to coronavirus epidemic, CECT was not performed at plane 6-weeks postpartum interval, but at 12 weeks and revealed complete recanalization of right ovarian vein (Figure 2). At her follow-up she had not experienced recurrence of symptoms while being maintained on anticoagulation therapy. Anticoagulation therapy was finished 12 weeks after delivery due to thrombosis resolution and negative DNA testing of inherited thrombophilia.

2. CECT 12 weeks after delivery: complete recanalization of right ovarian vein (green mark)

DISCUSSION

The most common postpartum thromboembolic events include deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary emboli. However, ovarian vein thrombosis complicates 0.05–0.18% of pregnancies. Mode of delivery was felt to impact on POVT formation with an incidence of 0.02% in normal deliveries, 0.1% in caesarean sections and 0.7% of twin caesarean sections [18]. It is extremely rare to find POVT without identified etiology and, hence, idiopathic OVT is only described as case reports throughout the literature [18].

Pathogenesis

The pathophysiology of ovarian vein thrombosis is ascribed to Virchow’s triad of hyper-coagulability, venous stasis, and endothelial trauma. It occurs in the right side in 70–90% of cases, bilaterally in 11–14%, and the left ovarian vein involve only 6% of cases [1, 5, 12, 13].

It is hypothesized that OVT commonly occurs on the right side because the right ovarian vein is longer than the left and it lacks competent valves. The right ovarian vein enters the inferior vena cava antero-laterally at an acute angle, which makes it more susceptible to compression. Furthermore, the dextrorotation of the enlarged uterus that occurs in pregnancy can cause compression of the right ovarian vein, and the right ureter as they cross the pelvic rim, which causes stasis of blood leading to thrombosis. It has been supposed that there is anterograde flow in the right ovarian vein (which predisposes to right-sided thrombosis) as compared to the retrograde flow in the left ovarian vein [9, 12]. This flow pattern was confirmed in four postpartum women using contrast venography, which showed left-sided retrograde flow on standing [6].

Clinical presentation and differential diagnosis

Ninety percent of POVT present within 10 days postpartum. POVT in up to 80% of patients may present with fewer (persists despite antibiotics), in 50% with right lower quadrant abdominal pain, many patients have vague diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, malaise and ileus. A mass in the adnexa that represents the thrombosed vein and surrounding inflammatory mass can be found in approximately half of cases on deep palpation [6, 7].

The differential diagnosis includes most conditions that affect the abdominal lower quadrant such as acute appendicitis, inflammatory bowel diseases, pyelonephritis, urinary tract infection, adnexal torsion, puerperal endometritis and tubo-ovarian abscess, peritonitis. Therefore, imaging studies are essential to establish the diagnosis of OVT [6, 7].

Investigations

In cases where postpartum women present with abdominal pain and fever, prompt diagnosis should be done, because risk of life-threatening complications. Investigations including a full blood count, urea and creatinine, CRP, lactate and cultures, hence sepsis is often first suspected [6, 15].

POVT may be second suspected, hence is accompanied by leucocytosis in 70–100% of women, but this is not a specific marker. White cell count and CRP have higher reference ranges through pregnancy and delivery, and declining to non-pregnant levels at 8 weeks postpartum. Therefore, raised levels of these parameters in a postpartum woman may not indicate thrombus or infection. Benefit may be in their serial measurement when rising levels indicate further investigation [6].

Diagnostic imaging techniques

POVT diagnosis in past was made on abdominal palpation of tenderness in the right lower quadrant with pain ora rope-like mass, followed by examination under anaesthetic or laparotomy. Recently imaging techniques such as ultrasound, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have become established as non-invasive diagnostic tools [6].

Ultrasound of the abdomen and pelvis is often the first imaging carried out. Because sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of colour-Doppler ultrasound reported as 55.6 %, 41.2 % and 46.2 % respectively, ultrasound is relatively poor for detection of POVT. A thrombosed ovarian vein on ultrasound is identified as an anechoic to hypo-echoic tubular mass extending between the adnexa and the inferior vena cava retroperitoneally with absent waveform on Doppler ultrasound. However, ultrasound is operator dependent and can be limited in obesity. Moreover, overlying bowel gas can cause confusion between POVT, the appendix and hydro-ureter, ultrasound for detection of POVT is relatively poor [6, 11].

CECT has been used to confirm POVT with a sensitivity &specificity 63–100% & 77.8–90% [3]. Diagnostic criteria include visualisation of the enlarged postpartum ovarian vein as a tubular retroperitoneal structure with low attenuation within the lumen and sharp enhancement of the vessel wall with perivascular inflammatory stranding [6].

MRI has the highest sensitivity and specificity that approaches 100% [11]. The features of POVT are similar to that on CECT. In addition MRI involves multiple planes and, because of increased sensitivity of paramagnetic iron, it can differentiate between flowing blood, acute thrombus (less than 1 week old) and subacute thrombus (1 week to 1 month old) [6]. Based on the information available nowadays, MRI is not clear “gold standard” for the diagnosis of POVT. Disadvantage of MRI is not available in most units as CT [3, 6].

Complications

The main complication is pulmonary embolism (25%) which results in death in 5% of cases. If POVT is not diagnosed, the disease could extend into the inferior vena cava or iliofemoral or renal vessels and lead to pulmonary embolisation. Furthermore, other complications include ovarian abscess, ovarian infarction, uterine necrosis, sepsis, ureteral obstruction, hydronephrosis, renal failure with dialysis [6, 14]. However ovarian vein thrombosis can resolve spontaneously, but considering the potential catastrophic consequences, anticoagulation is usually recommended [19]. Recurrence of POVT in subsequent pregnancy is low [6, 7].

Management

There is still no single recommended POVT treatment regimen [10]. In the past operative interventions (ligation of ovarian veins or the inferior vena cava and/or hysterectomy) often after antibiotics failure, or surgical excision of the OVT was the mainstay of treatment until 1970 and had an associated mortality of 53% [3, 6]. Intravenous antibiotics and heparin based on clinical presentation remain the treatment choice today. But there are no specific guidelines in place for duration of antibiotic and heparin treatment [6, 9, 14].

Brown et al. in 14 randomized patients study not revealed difference of fever resolution between women with septic thrombophlebitis who received antibiotics (“triple therapy” empiric regimen = gentamicin, clindamycin, ampicillin with cure rates of > 90 %) and women who received antibiotic + anticoagulant therapy after 5 days of fever refractory to antibiotics. But it thus appears, that septic phlebitis has a different pathogenesis than is bland pelvic thrombosis and is without the latter´s known propensity to thromboembolism [5]. In cases of suspected sepsis is advice combination of piperacillin/tazobactam or carbapenem + clindamycin [6, 15]. Studies with antibiotic/heparin therapy were limited by the fact, that POVT was considered only among patients not responding to antibiotic therapy. In more studies all women received anticoagulant therapy with or without antibiotics at the time of diagnosis with good outcomes [3]. Some authors recommended broad spectrum antibiotics for 7 to 10 days [6, 7]. If fever persists, consultation with microbiologist is appropriate [6].

Anticoagulation treatment of POVT can either be LMWH or warfarin therapy. The ability to administer and comply with treatment and follow-up may be a factor in deciding which anticoagulant is suitable for a patient [17]. LMWH is the agent of choice for both - antepartum and postpartum period. LMWH is thought to be very effective and safer than un-fractionated heparin (there is less risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, osteoporosis, fractures). LMWH requires no monitoring, except in patients with extremes of body weight [17]. The conditions increasing bleeding risk should also be considered when recommending anticoagulation, therefore haematologist consultations are advised. A full blood count, coagulation screen, urea and electrolytes and liver function tests should be taken before commencing therapy [6, 17].

Warfarin is considered safe during breastfeeding, and is an acceptable alternative, in women where daily injection is unacceptable [6]. It initially requires close monitoring for dose optimisation, especially in the first 10 days of treatment. In addition careful consideration should be given to loading with warfarin while the woman is continuing on antibiotics (as in newly diagnosed POVT) as polypharmacy can affect the international normalised ratio (INR) [16].

There is no definite guideline regarding the duration of anticoagulation therapy. Although resolution of POVT has been documented after only 7–14 days of treatment, but longer duration was reported too. Treatment duration of 3 to 6 months is considered necessary according radiologically documented resolution of thrombus [3, 6, 7].

In patients with hypercoagulable disorders, anticoagulation may need to be lifelong therapy [19]. In rare cases of persistent OVT or contraindication to pharmacologic management, an inferior vena cava filter or surgical intervention to ligate or excise the ovarian vein or even to perform caval thrombectomy can be considered [6, 16].

Prophylactic doses of anticoagulants are recommended in future pregnancy and 6 weeks postpartum for women with history of POVT [6, 7].

Patient, from presented case report, lacked any risk factor from the reported 33 risk factors for all venous thromboembolism except for the “hormonal changes in pregnancy” [6, 16]. Interestingly the patient did not experience POVT in her previous two pregnancies. Septic fever not responding to antibiotic therapy, aching right flank pain and CECT revealed thrombosis of the right ovarian vein. After introducing of the anticoagulation therapy combined with previously introduced antibiotic therapy, the patient was on the 5th day without fever and pain. Subsequently the anticoagulation therapy was discontinued after CT confirmed recanalization of the mentioned ovarian vein thrombosis.

CONCLUSION

Due to potentially life-threatening complications such as sepsis and pulmonary embolism, prompt diagnosis and treatment of POVT are important. It occurs most commonly on the right side. MRI and CECT are associated with higher sensitivity and specificity in detection of OVT compared to colour Doppler ultrasound. For symptomatic POVT many authors suggest anticoagulation for 3 to 6 months (until there is radiologically confirmed thrombus resolution) with the addition of antibiotics for 7 to 10 days (in the case of suspected infection). Multidisciplinary approach including obstetrician, haematologist, (interventional) radiologist, microbiologist and vascular surgeon is important.

Corresponding author

Miroslav Korbel, MD, PhD, assoc. professor

1st Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics

Faculty of Medicine Comenius University and University Hospital

Antolská 11

851 07 Bratislava

Slovakia

e-mail: miroslav.korbel@post.sk

Sources

1. Akinbiyi, AA., Nguyen, R., Katz, M. Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis: two case and review of literature. Case Rep Med, 2009, 2009, 101367.

2. Austin, OG. Massive thrombophlebitis of the ovarian vein thrombosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1956, 72, p. 428–429.

3. Bannow, BTS, Skeith, L. Diagnosis and management of postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2017, 2017, 1, p. 168–171.

4. Basili, G., Romano, N., Bimbi, M., et al. Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. JSLS, 2011, 15, 2, p. 286–271.

5. Brown, CE., Stettler, RW., Twickler, D., et al. Puerperal septic pelvic thrombophlebitis: incidence and response to heparin therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1999, 181, 1, p. 143–148.

6. Dougan, C., Phillips, R., Harley, I., et al. Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. Obstet Gynaecol, 2016, 18, p. 291–299.

7. Jenayah, AA., Saoudil, S., Boudaya, F., et al. Ovarian vein thrombosis. Pan Afr Med J, 2015, 21, 251.

8. Johnson, A., Wietfeldt, ED., Dhevan, V., et al. Right lower quadrant pain and postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. Uncommon but not forgotten. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2010, 281, p. 261–263.

9. Khalid, S., Khalid, A., Daw, HA. Case of postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. Cureus, 2018, 10, 2, e2134.

10. Klima, DA., Snyder, TE. Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. Obstet Gynecol, 2008, 111, 431–435.

11. Kubik-Huch, RA., Hebisch, G., Huch, R., et al. Role of duplex color Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography and MR angiography in the diagnosis of septic puerperal ovarian vein thrombosis. Abdom Imaging, 1999, 24, 85–91.

12. Narayanmoorthy, S., Ganesan, P., Ramanan, R. A rare case of postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol, 2015, 4, 3, p. 878–880.

13. Prieto-Nieto, MI., Perez-Robledo, JP., Rodriguez-Montes, JA., et al. Acute appendicitis-like symptoms as initial presentation of ovarian vein thrombosis. Ann Vasc Surg, 2004, 18, 481–483.

14. Ribeiro, A. Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis: Clinical case. Obstet Gynecol Rep, 2019, 3, 2, p. 1–3. doi: 10.15761/OGR.1000136.

15. RCOG. Bacterial sepsis following pregnancy. RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 64b. RCOG, 2012.

16. RCOG. Reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium. RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 37a. RCOG, 2015.

17. RCOG. Thromboembolic disease in pregnancy and the puerperium: acute management. RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 37b. RCOG, 2015.

18. Salomon, O., Dulitzky, M., Apter, S. New observations in postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis: experience of single centre. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis, 2010, 21, 1, p. 16–19.

19. Wysokinska EM., Hodge D., McBane RD. 2nd. Ovarian vein thrombosis: incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism and survival. Thromb Haemost, 2006, 96, 2, p. 126–131.

Labels

Paediatric gynaecology Gynaecology and obstetrics Reproduction medicine

Article was published inCzech Gynaecology

2020 Issue 4-

All articles in this issue

- What next in cervical cancer screening?

- Assisted reproductive methods – current status and perspectives

- Description of diagnosis of 45,X/46,XY ovotesticular DSD

- Vernix caseoza – composition and function

- Urinary incontinence: vaginal delivery versus instrumental delivery

- Importance of the genetics in the diagnostics of hydatidiform mole

- Cesarean scar defect – manifestation, diagnostics, treatment

- FATWOO – female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin

- Benefits of exercise in the prenatal and postnatal period

- Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis: case report and review of literature

- Czech Gynaecology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Cesarean scar defect – manifestation, diagnostics, treatment

- What next in cervical cancer screening?

- Assisted reproductive methods – current status and perspectives

- Benefits of exercise in the prenatal and postnatal period

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career