-

Medical journals

- Career

Intraosseous haemangioma od the zygoma - case report and literature review

Authors: I. Němec

Authors‘ workplace: University Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic ; Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Maxillofacial Surgery, 3rd Faculty of Medicine of Charles University and the Military

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 60, 1, 2018, pp. 26-29

INTRODUCTION

Intraosseous haemangioma accounts for less than 1% of all bone tumours (1–6). It is found most commonly in the spine and in the skull (2, 3, 7–9, 10). In facial bones, a haemangioma may occur in the maxilla, mandible and in nasal bones (3, 5, 6, 8, 10). The finding of haemangioma in the zygoma is rare (1, 3, 6, 10, 11). This paper presents a patient with intraosseous cavernous haemangioma of the zygoma.

CASE REPORT

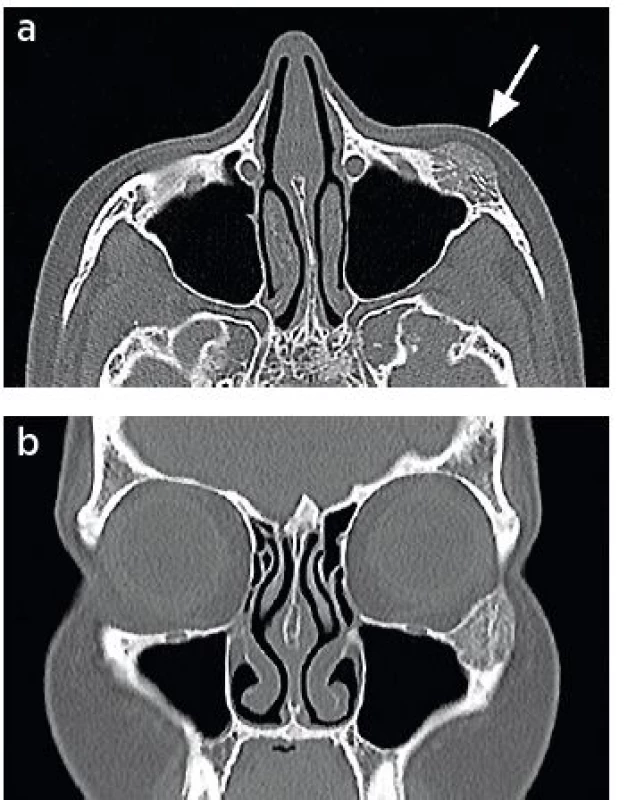

A 40-year-old female patient has observed a solid mass in the zygoma on the left (Fig. 1 a, b) for 8 years. In the most recent 3 months, the patient began feeling pain at the site of the mass and the mass slightly increased. The patient also observed swelling of the cheek area on the left. No injury to the cheek area was reported. Clinical assessment showed deformation of the cheek area on the left; no swelling was present and appearance of the skin was normal. Computed tomography (CT) assessment showed a clear expansion in the zygoma sized 23 x 19 x 14 mm, which was pushing the bone structure apart. The expansion showed a honeycomb structure without perifocal sclerosis. The tumour reached into the frontal and maxillary process of the zygoma. External and internal corticalis of the zygoma was thinned. No alterations were visible in soft tissues in the area of the expansion (Fig. 2 a, b). The lesion was visible already in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans taken in the patient 2 years before the CT assessment. The MRI assessment was performed due to problems of the patient unrelated to the lesion. The axial T2-weighted image showed a solid expansive lesion sized 15 x 10 mm in the lower edge of the left orbit without any perifocal oedema. The left maxillary sinus was filled with air (Fig. 2 c).

1. a, b. Patient with visible bulging of the cheek region on the left (arrow).

2. a, b. The CT scan shows a lesion in the left zygoma sized 23 x 19 x 14 mm. The corticalis is thinned; the surrounding soft tissues are unaltered (arrow)

Fig. 2c. MRI completed 2 years before the CT assessment. The axial T2-weighted image indicates a solid expansive lesion sized 15 x 10 mm in the lower edge of the left orbit without perifocal oedema. The left maxillary sinus is filled with air (arrow)

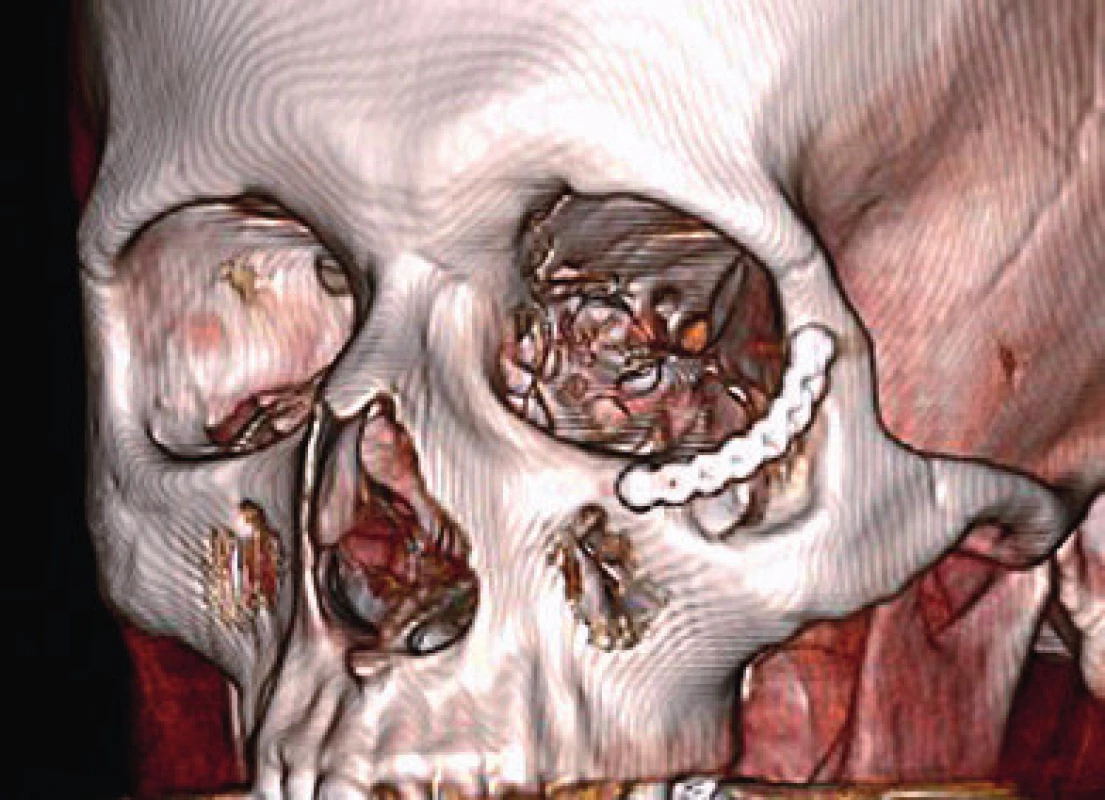

Under general anaesthesia, from subciliary incision we reached the lower edge of the orbit, at the place of the mass. The tumour was completely resected. The resected tissue included a border of healthy bone. Bleeding during the surgery was minimal. The resulting defect was bridged using a titanium miniplate. No complications occurred during the postoperative period. Cavernous haemangioma was demonstrated based on histology. A good cosmetic effect was seen after 5 months from the surgery (Fig. 3 a, b). Follow up CT and MRI assessments showed no recurrence or residue of the tumour. Three-dimensional CT scan showed a postoperative defect bridged with the titanium miniplate (Fig. 4).

1. a, b. Condition after 5 months from the surgery (arrow)

3. Three-dimensional CT scan after 5 months from the surgery. The postoperative defect of the zygoma bridged with the titanium miniplate is visible in the scan

DISCUSSION

Intraosseous haemangioma is a benign vasoformative neoplasm or developmental condition of endothelial origin according to the World Health Organization (12). The first haemangioma in the skull was described by Toynbee in 1845. Two tumours were present in parietal bones (13). In 1950, Schofield was the first to describe haemangioma in the zygoma (14).

Intraosseous haemangioma most commonly develops in the 4th to 5th decade of life (4, 8, 15–17). It is more common in women than in men (1–3, 6, 8, 9). Various haemangioma variants are recognized (12). Many facial haemangiomas are cavernous (15, 18). As regards to aetiology of haemangiomas, a congenital cause has been reported. In addition, a possible association with a prior trauma has been mentioned (8, 9, 19, 20).

Intraosseous haemangioma may cause swelling (2, 19) and deformity of the zygomatic region (2, 8) and of the orbit (2). Protrusion of the eye bulb and diplopia may develop (2, 9, 15, 18, 19, 20). Strabismus may also appear (20). Patients may suffer from pain (2, 8, 15, 18), and bleeding may occur (15, 18).

Preoperative assessments include CT and MRI (1, 9). As reported by some authors, routine preoperative angiography is not necessary given that it may not provide evidence of blood supply in many patients (2, 3, 18, 20). Although biopsy usually makes it possible to determine the diagnosis, it poses a risk of bleeding, which may be difficult to manage (19). A circumscribed lesion of the zygoma was clearly visible in the CT scans. The assessment confirmed a finding of an MRI assessment performed 2 years ago. Given the extent of the finding and its localisation, angiography and biopsy were not indicated before the surgery.

Bucy and Capp in 1930 were the first to describe haemangiomas in various parts of the skeleton including the skull based on classic x-ray imaging (21). In 1949, Wyke published a paper where he described haemangiomas in an x-ray image found in the skull (22). Basic x-ray assessment of the skull indicates an intradiploic, well circumscribed expansion – rarefaction with a honeycomb configuration on axial views and a classic sunray pattern of trabeculation in tangential views (23), usually without any reactive sclerosis of the edges (17, 23). This classic feature may be absent in many cases and instead, it may be presented only as lytic or dense bone expansive masses (23).

The trabeculae of bone and the corticalis are well visible in the CT scans. Appearance in the CT scans is variable, and the calvaria most commonly shows a characteristic sharply circumscribed expansive lesion with intact inner and outer tables and a sunburst pattern of the radiating trabeculae. “Soap bubble” and “honeycomb” configuration may also occur (1).

The surrounding soft tissues are well shown on MRI scans (1). Some authors have advocated magnetic resonance imaging as superior for evaluation of highly vascularized lesions such as intraosseous haemangiomas (18). As described by Moore et al., in cases where a round, potentially benign bone lesion is initially detected on MRI, the lesion may be confused with other disease processes, including malignancy (1).

Malignant transformation of the haemangioma has been described in association with radiotherapy (1, 2, 18). In particular, fibrous dysplasia, multiple myeloma, osteoma, numerous sarcomas, metastatic tumours and osteomyelitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis (15).

In many cases, haemangioma can only be observed (15, 18). Indications for therapy include correction of a mass effect, control of haemorrhage and cosmetic deformities (10, 15, 18). Removal of the tumour including an edge of healthy bone usually provides a definitive cure; recurrences are rare (1). Complete resection of the tumour is preferred also by other authors (3, 9, 11, 23). Partial resection of the tumour can also be considered (15, 18). Curettage of the tumour mentioned by some authors entails the risk of uncontrolled bleeding (1, 6).

Some authors recommend preoperative angiography and embolization to reduce the risk of bleeding (1, 16). According to other publications, bleeding prevention is not necessary provided that the edge of healthy bone is also resected with the tumour (2, 3).

The zygoma is of crucial importance for aesthetics of the face and its symmetry (2). After excision of the haemangioma, the defect should therefore be reconstructed using some implant type (3, 6, 11, 18, 20). Primary reconstruction prevents the soft tissues from contracting (15).

In our patient, it was possible to resect the tumour with an edge of healthy bone. Bleeding during the surgery was minimal. The resulting bone defect was primarily bridged using a titanium miniplate, which was sufficient to prevent postoperative deformation of the cheek region, and particularly, any potential deformation of the lower eyelid (Fig. 3, 4).

CONCLUSION

Intraosseous haemangioma is a benign lesion, which is found only rarely in the zygoma. Preoperative assessments include CT and MRI. Complete resection of the tumour with an edge of healthy bone prevents any major bleeding during the surgery and any later recurrence of the tumour. Primary reconstruction of the defect should be undertaken to prevent any major cosmetic deformation of the cheek region.

Corresponding author:

Ivo Němec, M.D.

Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Maxillofacial Surgery,

3rd Faculty of Medicine of Charles University and the Military University Hospital Prague

U Vojenské nemocnice 1200

169 02 Prague 6, Czech Republic

E-mail: Ivo.Nemec@uvn.cz

Sources

1. Moore SL, Chun JK, Mitre SA, Som PM. Intraosseous hemangioma of the zygoma: CT and MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001 Aug;22(7):1383-5.

2. Ramchandani PL, Sabesan T, Mellor TK. Intraosseous vascular anomaly (haemangioma) of the zygoma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004 Dec;42(6):583-6.

3. Konior RJ, Kelley TF, Hemmer D. Intraosseous zygomatic hemangioma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999 Jul;121(1):122-5.

4. Madge SN, Simon S, Abidin Z et al. Primary orbital intraosseous hemangioma. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009 Jan-Feb;25(1):37-41.

5. Dhupar V, Yadav S, Dhupar A, Akkara F. Cavernous hemangioma - uncommon presentation in zygomatic bone. J Craniofac Surg. 2012 Mar;23(2):607-9.

6. Savastano G, Russo A, Dell’Aquila A. Osseous hemangioma of the zygoma: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997 Nov;55(11):1352-6.

7. Gupta T, Rose GE, Manisali M, Minhas P, Uddin JM, Verity DH. Cranio-orbital primary intraosseous haemangioma. Eye (Lond). 2013 Nov;27(11):1320-3.

8. Marshak G. Hemangioma of the zygomatic bone. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980 Sep;106(9):581-2.

9. Sweet C, Silbergleit R, Mehta B. Primary intraosseous hemangioma of the orbit: CT and MR appearance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997 Feb;18(2):379-81.

10. Pinna V, Clauser L, Marchi M, Castellan L. Haemangioma of the zygoma: case report. Neuroradiology. 1997 Mar;39(3):216-8.

11. Zins JE, Türegün MC, Hosn W, Bauer TW. Reconstruction of intraosseous hemangiomas of the midface using split calvarial bone grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Mar;117(3):948-53; discussion 954.

12. Adler CP, Wold L. Haemangioma and related lesions. In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, eds. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press, 2002.

13. Toynbee J. An account of two vascular tumours developed in the substance of bone. Lancet, 1845; 2 : 676.

14. Schofield AL. Primary hemangioma of the malar bone. Br J Plast Surg. 1950 Jul;3(2):136-40.

15. Marcinow AM, Provenzano MJ, Gurgel RK, Chang KE. Primary intraosseous cavernous hemangioma of the zygoma: a case report and literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2012 May;91(5):210, 212, 214-5.

16. Colombo F, Cursiefen C, Hofmann-Rummelt C, Holbach LM. Primary intraosseous cavernous hemangioma of the orbit. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001 Jan;131(1):151-2.

17. Slaba SG, Karam RH, Nehme JI, Nohra GK, Hachem KS, Salloum JW. Intraosseous orbitosphenoidal cavernous angioma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1999 Dec;91(6):1034-6.

18. Cheng NC, Lai DM, Hsie MH, Liao SL, Chen YB. Intraosseous hemangiomas of the facial bone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Jun;117(7):2366-72.

19. Riveros LG, Simpson ER, DeAngelis DD, Howarth D, McGowan H, Kassel E. Primary intraosseous hemangioma of the orbit: an unusual presentation of an uncommon tumor. Can J Ophthalmol. 2006 Oct;41(5):630-2.

20. Valentini V, Nicolai G, Lorè B, Aboh IV. Intraosseous hemangiomas. J Craniofac Surg. 2008 Nov;19(6):1459-64.

21. Bucy PC, Capp CS. Primary hemangioma of bone with special reference to the roentgenological diagnosis. Am J Roentgenol 1930;23 : 1-33.

22. Wyke BD. Primary hemangioma of the skull: a rare cranial tumor: review of the literature and report of a case, with special reference to the roentgenographic appearances. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther. 1949;61 : 302-16.

23. Banerji D, Inao S, Sugita K, Kaur A, Chhabra DK. Primary intraosseous orbital hemangioma: a case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1994 Dec;35(6):1131-4.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2018 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Pedicled pectoralis major flap in head and neck reconstruction - technique and overview

- Securing intraoral skin grafts to the floor of the mouth: case report and technique desription

- Intraosseous haemangioma od the zygoma - case report and literature review

- Editorial

- Pedicled pectoralis major flap in head and neck reconstruction - our experience

- In memoriam: Professor Rajko Doleček

- Commemoration of professor Miroslav Fára, M.D., DSc.

- Use of licap and ltap flaps for breast reconstruction

- Image Possibilities of the Peripheral Nerve Tumor Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging - Case Report

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Pedicled pectoralis major flap in head and neck reconstruction - technique and overview

- Use of licap and ltap flaps for breast reconstruction

- Editorial

- Intraosseous haemangioma od the zygoma - case report and literature review

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career